Gordon Grice's Blog, page 87

August 5, 2011

Polar Bear Kills One, Injures Four

This story is peculiarly similar to the recent one about a brown bear attack in Alaska. In both cases, teens were on a wilderness expedition. But whereas the Alaska case involved a sow defending her cubs against a perceived human threat, this one looks like a bear in predatory mode.

Attacks by polar bears are rare because their range is largely outside ours. A high percentage of their attacks are predatory.

'Hungry' polar bear mauls British tourist to death in horrific attack | News:

"A British boy aged 17 was mauled to death today when a polar bear attacked a group of students on a remote Norwegian island.

Four others, including two teenage boys, were injured by the starving animal at 7.36am on Spitzbergen."

UPDATE: More information and a video interview with a survivor's father.

Thanks to Steve V. for the news tip.

Published on August 05, 2011 14:42

Victim of Alaska Bear Attack Speaks

New Mexico teen recounts Alaska bear attack - WSJ.com:

"Noah watched as the bear attacked two of his friends and then disappeared. But the grizzly returned moments later and charged Noah. The bear swatted him to the ground with a single swipe before biting his chest and puncturing a lung.

'I was just thinking, 'How is this real?'' he told the Albuquerque Journal on Tuesday in his home. 'Things like this don't happen to people.'

After the grizzly bit him, Noah said he looked up and saw the bear towering 10 feet above him.

'It reared up and was standing over me on its hind legs,' he said."

"Noah watched as the bear attacked two of his friends and then disappeared. But the grizzly returned moments later and charged Noah. The bear swatted him to the ground with a single swipe before biting his chest and puncturing a lung.

'I was just thinking, 'How is this real?'' he told the Albuquerque Journal on Tuesday in his home. 'Things like this don't happen to people.'

After the grizzly bit him, Noah said he looked up and saw the bear towering 10 feet above him.

'It reared up and was standing over me on its hind legs,' he said."

Published on August 05, 2011 13:38

August 4, 2011

Death Stories: Breath, Conclusion

At Pleasant Ridge again the wind is wild and hot, and a hawk seems to be playing with it, letting it outwrestle him for a moment and then slipping away to show his mastery. He flips upside down and rides so low I can see the brown speckles in the cream of his belly, can even follow for a moment the ropy folds of muscle in his breast. I am coming on, fastening the iron gate behind me, catching my breath against the desiccating wind, and he takes his time, as if to show me I'm no threat. He turns over through some impossible angle, tracing out a Moebius strip, and then he stoops and takes something from the ground and is instantly up and gone, though I have miles of sky and should be able to see him still. I had only a quick impression of the thing he took from the ground: the dangling spaghetti tail of a rodent.

I stumble and stagger trying to get closer with my eyes turned to the sky. The hawk means nothing but itself, and I tell myself that several times, though his fleshy chest continues to seem an affront, an allusion to the very idea of flesh. To the flesh undoing itself beneath my feet.

This story first appeared in different form in Mayborn.

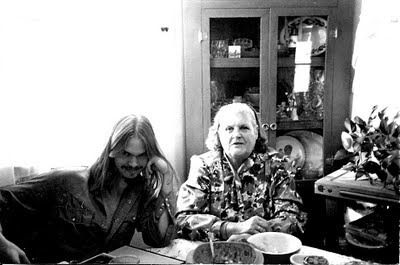

Photo by Wayne T. Allison

Published on August 04, 2011 10:08

August 3, 2011

Death Stories: Breath, Part 4

Her death was a lingering business with oxygen tank, wheel chair, ambulance rides; in her final days the stories failed her; too little breath to speak them. Her heart drowned in its bag of waters.

Now I feel it all over again: Granddad Tom has died, and we've been through his things, and among them were her things. That's her new death. In their cabinets and boxes I find a plastic cup with a barrette clipped to its lip. A ball of soap. A keychain with TOM in red letters. Cuticle scissors; a Q-tip. "An audio adaptation" of a Louis L'Amour novel. A double-barreled packet of salt from Mr. Burger. A plastic grocery bag full of bullets in various denominations—some boxed, some loose. A box of yarn; palm-sized bits of crochet. The right lens of a pair of eyeglasses. The cap of a Bic pen. Buttons, paper clips, postage stamps used but uncancelled, strips of trading stamps in a pocketbook. Combs, pens, earrings, blank tags for Christmas gifts, unopened boxes of silverware. The plastic cover for a Gillette disposable razor. An hourglass made of clouded brass. A receipt from County Handicrafts of Milwaukee on which is written "Teach 2 mos. to Feb. 87." What this might mean, and what either of my grandparents was doing in Milwaukee, I can't say. Dozens of pill vials, containing medications current or twenty years out of date; cotton swabs, wedding rings. A bean dip can packed with marigold seeds; a label dates them five years old and advises one to store them in the freezer. A human molar with a dark caries at the base, rimmed with a rust-stain of blood, a dried knot of pulp lingering inside it.

The books, veiled in spider web so laden with dust it feels like velvet—when I move a volume, the web tears silently and falls in curls. In a closet all her clothes hang. He never wanted to let them go—it would be like letting her move out, granting her the right not to be there in the mornings. The family didn't push him to give away the clothes: they would be sent to charity, and then we might see someone else walking around town in them. Among the skillets, the scat of mice. Beneath the toaster, an actual mouse, accidentally cooked. Its tail lies, innocuous, on the counter for days until someone finds out, by tugging, what it is.

His death is their death. She has been dead almost thirteen years, and the memory of her is suddenly out of phase, parts of it seeming ancient, her death news from the era before I had children to watch over, even from the era before I had kissed my stillborn first child's brow and smelled the disinfectant and blood mingled with her baby smell. Other memories of Lavon seem suddenly fresh, like a half-healed wound under a torn scab. A New Year's Eve, three weeks after she died. My mother-in-law sent me to the liquor store for champagne and Silver Bullets. I looked around guiltily as I walked into the store. I was legal, but this was my hometown and my kinsmen were Christians of the doom and thunder school and I might be seen any minute.

The woman who rang me up looked twice at my ID. I thought she was going to question my age, but instead she said, "Were you related to Lavon?" And she told me how she had loved Lavon, all about the kindnesses done and the eyes that meant Lavon was listening, really listening, not watching for an opportunity to speak.

In the parking lot, crescents of crisp snow seemed as bright as the buzzing street light. Lavon would not have liked to see me in a liquor store.

Published on August 03, 2011 10:45

August 2, 2011

Black Bear vs. Athlete

Former U.S. ski team member attacked by bear | Off the Bench:

"The bear chased her down from behind, slashing her chest and left arm with its claws when Haas turned around. No one on the trail heard her screams."

Yet another black bear attack. I don't for a minute believe the woman's punch "forced" the bear onto all fours. Bears are far stronger and tougher than people. But it probably did help discourage the bear.

"The bear chased her down from behind, slashing her chest and left arm with its claws when Haas turned around. No one on the trail heard her screams."

Yet another black bear attack. I don't for a minute believe the woman's punch "forced" the bear onto all fours. Bears are far stronger and tougher than people. But it probably did help discourage the bear.

Published on August 02, 2011 17:18

Death Stories: Breath, Part 3

Among the neighboring stones, a couple who died of flu the month Lavon was born—her own grandparents. Another stone right next to Lavon's, a thin white one veined with gray, bearing the name of an infant. He was the first dead child in her life, not her own child, but her brother, though she took care of him. She was four; her younger sister was sick with whooping cough, her life feared for. Lavon was charged with feeding the baby boy, washing him. One day while the parents cared for the sick girl, she fed the baby too much and he died. That is a senseless family story. A contradictory story claims the baby was born with a birth defect, his early death destined.

On the back of the baby brother's stone, faint scratches. I kneel. They're words, engraved but long since gone faint. I put my fingertips to them, and slowly, with eyes and touch and conjecture, puzzle them out. Simply the boy's name and dates again. She didn't like to leave him illegible, arranged to have the back of his stone inscribed and the stone turned around. I ask later, and the family tells me she arranged this in the last year of her own life. His death was with her, then, to the end, repeated like the burden of a song, carved in stone.

Published on August 02, 2011 10:43

August 1, 2011

Death Stories: Breath, Part 2

A mummified Native American child, six hundred years old and leathered in the dry caves where she used to play as a child. That was a story Lavon told me—going with her brothers to find arrowheads among the mesas, and then the news that a neighbor had brought out an ancient human body with rusted hair and skin hard as a boot.

Democritus bears witness that men first appeared in the form of small worms, which little by little assumed human shape; or, as Anaximander relates, on escaping from the womb of Earth they were enveloped in a kind of rough, spiny skin, not unlike the burr of a chestnut.

Francesco Redi

But the stories I remember most vividly from my childhood are the ones about dust. The wall of black cloud before which hawks and jackrabbits fled in panic. Midnight at noon. Tumbleweeds snagged on fences and catching dust until there was ground enough for the cattle to walk over the fences. Wet towels to block, ineffectually, the space beneath the door. The x-rays, decades later, that showed speckled lungs. I wish I could recreate them, these mood-pieces spun from her asthmatic sentences. Lavon told them to me during the lesser dust storms of my own childhood. I knew, even then, that I was supposed to carry the stories, that she meant for me to bear witness to what my silent and repressed kinsmen never would. What I learned from Lavon, whose life was so laced into this arid landscape, is that everything you have can die at once. The earth itself can rise up to carry it all away.

But this isn't right. She didn't advocate despair. That's only what I took from her story while she was trying to say something else. I am troubled these days by my realization that I have lost all the stories. Even the details I recall are mere salvage, gleanings from a river. Herodotus said a man never steps into the same river twice. I say a man never drinks from the river his ancestors drank from. Their stories have been lost in translation. They have become mere mystery.

The water you touch in a river is the last of that which has passed, and the first of that which is coming. Thus it is with time present.

Leonardo da Vinci

I have been faithful to her in my fashion. She dwelt on the stories of disaster. The fragments of her stories I get from the women in my family are, many of them, about surviving in a tent along the river (a literal river this time). She was a child, her parents broke, the entire world in Depression and dust. Another story, something she never told me because of its gynecological subject, but which my kin have retold: When Lavon was born, the midwife was a sort of witch-doctor who coaxed the baby through a difficult birth, applying jars of smoke to the mother's vulva. But I've heard the story several times now, and it changes. It was Lavon's own birth, or her brother's. The details drift.

The river where they camped is gone now. Its course still exists, marked by powdery soil and stunted cottonwoods. But it is dry, the water table exhausted by decades of farm irrigation. The river is receding into grassland and imagination.

Published on August 01, 2011 10:36

July 31, 2011

More Leopard Attacks in India

Steve Jurvetson/Creative Commons

Steve Jurvetson/Creative CommonsTwo injured in leopard attack - The Times of India:

"The leopard sneaked into Kuani Gaon from a nearby forest area around 7 pm on Friday and attacked some cattle. As the villagers tried to chase the animal away, it attacked them."

Published on July 31, 2011 16:33

Death Stories: Breath, Part 1

Twenty-eight miles of highway take me from my ancestral hometown: past the earthy stink of a beef feedlot and the wetter, nastier smell of barracks where hogs breed in confinement, past a five-mile stretch of open pocked ground visibly inhabited by prairie dogs and invisibly by the rattlesnakes that feed on them, past two road-killed skunks and a bull snake belly-up on the pavement, through a little town (convenience store, stoplight, churches, white siding, blistered whitewash, billboards, mud-ragged dog), past the Baptist church camp, to a certain dirt road. On this drive, the earth goes red: I've crossed the line between the coffee-black rich dirt to the northwest and the rusted soil to the southeast. Beside the dirt road: clattering yucca, wild pumpkin vines sprawled like dead spiders; two farmhouses, two rusting combines. An uncertain wooden bridge spans a dry creek, and abruptly I'm at a gate whose wrought-iron letters say 1907 PLEASANT RIDGE—not an address, but a date and name. Only the gate is iron; the rest of the fence is barbed wire stapled to red cedar poles. Nothing inside but headstones and buffalo grass.

Nothing for me to do except pick up what the wind has left of some plastic flowers and stuff them into the trash barrel. I read the stones, some of them a century old and bearing unlikely old-fashioned names like Little Jeneva Dumbell, who lived for 29 days in 1913. And also:

BABY GIRL JACKSON 1922 1922says one wafer of a stone, and next to it an identical wafer:

BABY GIRL JACKSON 1923 1923and next to it, another:

BABY GIRL JACKSON 1925 1925.

But those are the names of strangers.

It's my grandmother Lavon I came to see. She was a farmer and depended on irrigation for her bread. It is a dry place, the plain of the Panhandle, and the water table has been dropping for decades. Fifty years ago it became impossible to make a crop with rainfall alone. Nevertheless, Lavon nursed a special hatred for irrigation motors and their migraine noise. She'd listened to enough of that particular High Plains pest in life, and didn't want to be troubled with it in death, so she chose the quiet of Pleasant Ridge. It was a strange notion for a woman who'd gone into war zones to spread Christ. Her soul ought to have been elsewhere, but she provided for the comfort of the corpse. After she was buried someone put in an irrigation well over the rise, and now it sings its evil song to her bones all summer long.

Of the dead who are taken to be buried: The simple folk will carry torches to illuminate the journeys of those who have wholly lost the power of sight.Leonardo da Vinci

She was lying about the noise anyway. Surely it was her buried kin that made her want to sleep here. The gray stone for two, Granddad Tom's side heaped and fresh, Grandma Lavon's flat and grassed. The stone lists the names of their three grown children. Beneath these, in smaller print, are the names of two girls who never drew breath. Two of the five lost babies.

Their bodies are not really here; they are nothing but names. Blue babies; miscarriages. There are stories, scattered mostly among kinswomen, of these events: the unsuspected baby in the toilet, its human shape definite and dead. The daughter buried at the corner of a field, then, in repentance, exhumed and buried with her infant aunt. They all had names, found in my grandmother's hand on the back of an envelope after her death. I take this to mean that she was not leaving the names for others to find, only rehearsing them for herself. Her husband outlived her, but he died not knowing the names of his other three lost children—for I asked him once.

Published on July 31, 2011 10:29

July 30, 2011

Parson Spider

The parson spider is sometimes accused of having a dangerous bite, but that's a myth. My friend D'Arcy says she found this fellow in her crystal singing bowl. I didn't even know she had a crystal singing bowl. As a matter of fact, I didn't even know what a crystal singing bowl was.

Published on July 30, 2011 10:05