Gordon Grice's Blog, page 68

January 19, 2012

Indonesia: Crocodile Killed After Eating Teenager

Disturbing news item from Indonesia. Several species of crocodile live in this area, but the likely predator here is the saltwater croc.

Crocodile Killed After Eating Teenager | The Jakarta Globe:

"After killing the crocodile, people cut open its belly and found pieces of 14-year-old Rio Candra's body.

"Parents now forbid their children from taking a bath in the river to prevent them from being eaten by a crocodile," Syafullah said.

Rio was with his father, Syahrudin, looking for mangrove wood on the Merusi river when the crocodile attacked and dragged him into the water. His father, who witnessed the incident, could not do anything."

Thanks to Croconut for the news tip.

Published on January 19, 2012 09:00

January 18, 2012

Crow Goes Sledding

Is this play, or something harder to understand? I sometimes see crows standing atop the pines in thunderstorms, riding as the wind whips them about. It's not a safe place to be; the only reason I can think of for standing there is that it's fun.

Published on January 18, 2012 09:00

January 17, 2012

Invasion of the Grebes

In Utah, a massive flock of eared grebes smashed into snowy parking lots, apparently mistaking them for water. Yet another lesson about blindly following your leaders.

Thousands of Birds Dive-Bomb Utah Parking Lots - Yahoo! News:

"Thousands came down. They came down everywhere. We were able to rescue about 2,000, but most of them, of course, didn't survive the impact."

Published on January 17, 2012 09:00

January 16, 2012

What Is This?--Answers

Answers to yesterday's quiz:

1. The shed skin of a snake.

2. The feather of a pheasant.

3. The hide of a leopard slug.

4. A mushroom.

5. An orb-weaving spider.

6. The fur of a badger.

Photography by Nik Nimbus.

1. The shed skin of a snake.

2. The feather of a pheasant.

3. The hide of a leopard slug.

4. A mushroom.

5. An orb-weaving spider.

6. The fur of a badger.

Photography by Nik Nimbus.

Published on January 16, 2012 09:30

January 15, 2012

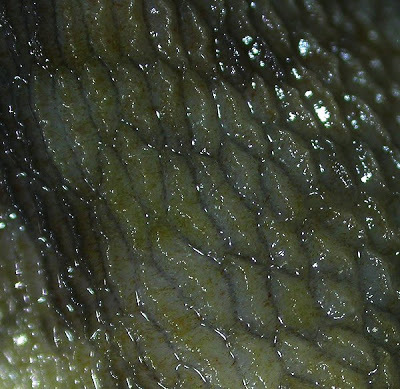

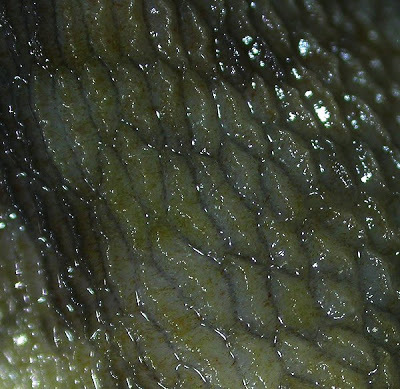

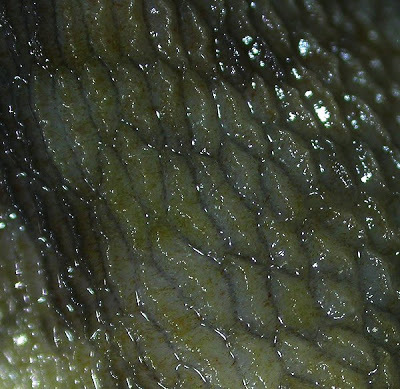

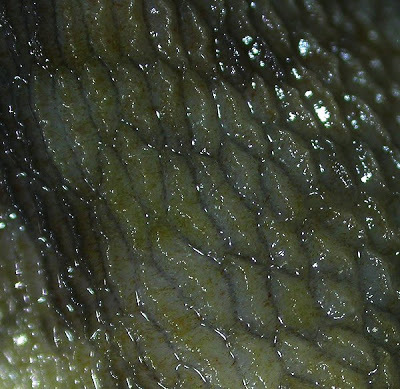

What Is This?

A quiz for you. Here are photos of half a dozen natural objects seen in extreme close-up. All of them are (or were) part of living things-- like, for example, a wombat's toenail. How many can you figure out?

Photography by Nik Nimbus.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Answers tomorrow. Hint: "wombat's toenail" is not actually one of the correct answers.

Photography by Nik Nimbus.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Answers tomorrow. Hint: "wombat's toenail" is not actually one of the correct answers.

Published on January 15, 2012 09:00

January 14, 2012

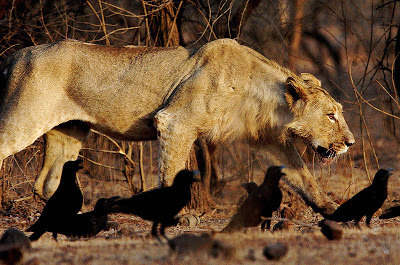

Lion and Leopard Attacks in India

Rupal Vaidya/Creative Commons

Rupal Vaidya/Creative CommonsFrom India, a report of an attack by an lion. As is usually the case when these rare Asiatic lions hurt people, the boy was trying to protect livestock. The article also mentions several recent leopard attacks. The one a few days ago in the Guwahati made headlines because it came with dramatic photos, but leopard attacks in rural areas of India are not unusual.

Lion attacks youth near Khambha - The Times of India:

"At least three persons have been attacked by leopards in close vicinity of Khambha.

'Wild animals are a common sight around Khambha as it is located close to the Gir forest. Presence of wild animals in the human habitat is also one of the reasons why the incidents of animal-human conflicts are on rise. However, incidences of lion attacks on human are rare compared to leopards in this year. There must be some conflict and disturbance to the lion behind the attack.'"

Related Post: Big Cat Attacks in the Gir Forest

Published on January 14, 2012 09:00

January 13, 2012

Hobo Spiders, Conclusion

Giant House Spider--cousin, competitor, and occasional predator of the hobo

Giant House Spider--cousin, competitor, and occasional predator of the hobo(The Book of Deadly Animals hits the US later this month. As with the recent UK release of the book, I'm going to celebrate by running here an expanded version of a story from the book.)

The hobo spider's danger to people is now widely recognized.The Centers for Disease Control list it (along with the widow and reclusespiders) as dangerous, medical textbooks concur, and publications like theJournal of the American Medical Association have published case studies.Doctors know the signs of hobo venom—a blistering wound ringed with yellow likethe moon in a halo of smog, devastating headache in many cases, disturbedthinking in an occasional one.

But skeptics remain. One is Greta Binford of Lewis and ClarkCollege. In an unpublished study, Binford and some colleagues at the Universityof Michigan attempted to replicate Vest's experiment. They were unable toproduce necrotic lesions by injecting hobo spider venom into rabbits. TheMichigan rabbits developed nothing worse than a red bump. Binford points outthat the hobo has never been implicated in human injuries in Europe, where ithas been known for centuries. She analyzed venom obtained from European andNorth American hobos and found no chemical differences.

Like several other prominent skeptics, Binford notes thatthe hobo spider is rarely caught in the act of biting and brought in foridentification by a competent specialist. Because the hobo's appearance is notespecially distinctive, the average bite victim can't be expected to sort itout from dozens of other spiders. Rod Crawford of the Burke Museum at theUniversity of Washington deals with hundreds of spider identifications eachyear. He points out that a species ID by a layman is virtually useless. Evendoctors get very little training in such identification and are likely to bemistaken. Still, Crawford is satisfied with Vest's evidence, which linked acaptured or crushed hobo with human symptoms in four cases.

But even here, it's possible to contest the evidence. RickVetter of the University of California, Riverside points out that one of thesevictims—the 42-year-old woman I mentioned earlier, who found a hobo spider inher clothing—had a history of phlebitis, a circulatory problem that sometimescauses necrotic lesions. The phlebitis, says Vetter, could have caused thesymptoms Vest blamed on the hobo. Vetter also notes that the Australianwhite-tailed spider, once widely accepted by doctors as a source of necroticarachnidism, has recently been exonerated. Researchers studied 130 cases ofdefinite white-tailed spider bites, finding not a single necrosis. Vetter wouldlike to see hobo bites subjected to a similarly rigorous study. He points outthat mistakes have serious consequences. For example, misdiagnosis of ailmentslike basal cell carcinoma, which can look like necrotic arachnidism, could befatal.

There's another complication: Venomous animals aren't alwaysvenomous. It has long been known that black widow spiders, like some venomoussnakes, can deliver "dry bites" to warn off larger animals withoutwasting venom on them. Typically, these are followed by a dose of venom if theharassment persists. Rebecca Vest, who worked with her brother Darwin in hisinvestigations (and who first proposed the name hobo spider to replace theinaccurate "aggressive house spider"), reports that dry bites arecommon for hobos. Widows vary in their toxicity with age, health, and gender,and these factors seem to come into play with hobo spiders as well. Forexample, male hobos pack a more potent venom than females. It is typically themale hobo, wandering away from its funnel-shaped web in search of a mate at theend of summer, that bites people.

People vary considerably in their reactions to venom. Only aminority of people, for example, show any lingering symptoms after a dose ofbrown recluse venom. I myself have been bitten by recluses a number of times.Though the stinging sensation I felt after a short delay made it clear that I'dbeen envenomed, I never developed a sore or any systemic symptoms. The wholeexperience was less painful than a mosquito bite—and, taking into account thepossibility of mosquito-borne disease, less dangerous. It may be that hobovenom is similarly selective. After all, its function is to subdue insects, andany effect it has on us comes about because we're related to insects. It wouldbe comforting to think that a few billion years of evolution have putconsiderable distance between us and our insect kin, but chemically, that's notthe case. We are only sometimes different enough to be immune to insect-killingvenoms.

Medical journals have attributed a handful of human deathsto the hobo spider. Crawford says perhaps 100 cases of medically significantbites are reported in Washington every year, but he adds that a physician'sdiagnosis is shaky evidence in the absence of the culprit. Like "recluse bite" beforeit, "hobo spider bite" has become what Binford calls "a medical dumpingground"—a default diagnosis when a better one can't be found.

Meanwhile, isolated cases have suggested that a few of thehobo's fellow agelinid spiders are occasionally dangerous. The Western grassspider (Agelenopsis aperta) has beenimplicated in a single human fatality. And a giant house spider (Tegenaria duellica) produced a serious injury in ahuman being—not because of venomous effects, but because of an allergicreaction.

*

The agelinidae are, as spiders go, remarkably tolerant ofeach other. I have seen a spindly male living on the fringes of a female's web,suffering no abuse from his larger mate. Perhaps he was helping to guard theeggs. I have seen, too, an entire bed of wandering jew covered with twenty orso discrete funnel webs, the inhabitants apparently unconcerned about theproximity of neighbors. But I've also seen what happens when two come intoconflict. A flurry of legs, then the sudden collapse of one spider. It folds upin the grasp of its enemy. The effect is something like a child's hand crushedin an adult's.

As it happens, this tendency for some agelinids to eatothers may help explain why the hobo has apparently harmed people in NorthAmerica but not in Europe. Darwin Vest, who considered pesticides anirresponsible way to control spiders, examined the question of what predatorsmight naturally control hobo populations. The most effective predators provedto be other spider species, like the cellar spider (Steatoda grossa) and theAmerican house spider (Achaearanea tepidariorum). Most effective of all was thegiant house spider, an agelinid with a leg span broad as a human palm. Thegiant is so closely related to the hobo that the two may interbreed, and it notonly preys on the smaller species, but also competes with it for food. Vestsuspected it was the giant that kept the hobo out of European houses all along.The giant has, in the last 25 years, established itself in the PacificNorthwest. Rebecca Vest reports that hobo populations in southern Idaho haveshrunk noticeably in that same period. It may be that the hobo, though equallyvenomous wherever it turns up, simply has fewer chances to bite in Europe. Andperhaps the same situation will eventually prevail here as the giant housespider, an unrecognized ally long ago suspected of spreading the Black Death,expands its range across America.

Published on January 13, 2012 09:00

January 12, 2012

Hobo Spiders, Part 3 of 4

Black Widow Spider (Photo by Hodari Nundu)

Black Widow Spider (Photo by Hodari Nundu)(The Book of Deadly Animals hits the US later this month. As with the recent UK release of the book, I'm going to celebrate by running here an expanded version of a story from the book.)

It used to be said that no US spider was really dangerous,and this view held sway well into the 1920s, despite well-attested reports ofdeaths from the bites of widow spiders. It was only after intrepid biologistslike William Baerg and Allan Blair subjected themselves to widow bites in thelab, and suffered horribly, that the prevailing opinion changed. It took thirtymore years for scientists to sort out the two syndromes apparently caused bywidow bites—one featuring extravagant pain spreading rapidly throughout thebody, the other the slow death of the flesh around the bite. Eventually it wasdemonstrated that the second syndrome should have been blamed all along on theunobtrusive recluse spiders.

That ought to clear everything up, but it hasn't.Specialists are routinely annoyed by pseudofacts claiming that the averageperson inhales four spiders per year in his sleep or that recluse bite symptomscan be cured with tazers. Many myths mix in a pinch of reality. The blushspider, for example, must have been inspired by the widow, which used to infestoutdoor toilets and bite people in the genitals. And the false reports of camelspider venom read like an exaggerated account of the true effects of reclusevenom.

It's taken a long time to sort out the truth behind hobospider bites. They produce symptoms similar to those caused by recluse venom,but they occur in areas outside the recluse's range—the Northwest quadrant ofthe US and adjacent parts of Canada. After the brown recluse's danger came topublic attention beginning in the 1950s, doctors in the Pacific Northwest beganto diagnose certain lesions as recluse bites. But these diagnoses didn't fitthe known range of the recluse. No member of its genus is regularly found inthe northern half of the US.

In the early 1970s, this mystery came to the attention oftoxinologist Darwin K. Vest, an autodydact whose work on cobras, rattlesnakes,and other venomous creatures had won him respect in scientific circles. Whileworking at Washington State University's Pullman campus, Vest learned that thezoology department there often received queries about "necroticarachnidism"—flesh-killing lesions apparently caused by spider bites. Vesttackled the problem by looking into the cases of 75 patients in the PacificNorthwest diagnosed with this affliction. He exonerated spiders in most ofthese injuries, blaming them on insect bites, cigarette burns, and othercauses. Vest surveyed the homes of 22 remaining patients. Collecting by handand with sticky traps, Vest and his team collected thousands of specimens. Noneof the homes yielded recluses, but sixteen of them revealed healthy populationsof the hobo spider. Sometimes a single sticky trap measuring about 15 by 30 cmwould fill with hobos overnight.

The presence of hobos in such numbers was suggestive, but itproved nothing. The average home in any temperate region is likely to hostseveral dozen species of spiders. Most people don't realize that they spendevery day of their lives close to spiders, so that seeing one the same day youget a bite or scratch proves nothing.

Vest decided to bring hobo spiders, and several othersuspect species, into the lab for tests. He and his team milked live spiderswith mild anesthesia and micro-pipettes under a dissecting microscope, workingcarefully so that the spiders could be released unharmed. The spiders were sosmall that the capillary action of the pipettes was often enough to draw venomfrom the fangs. When that technique didn't work, the researchers sometimes resortedto mild electric shock, using a nine-volt battery to make the venom glandscontract and prompt the release of a droplet or two. Since each spider producedonly a miniscule amount, the researchers had to milk a great many to obtain aworkable sample. Their result: The hobo spider venom produced necrotic lesionsin rabbits. To confirm this result, Vest shaved the backs of rabbits and held ahobo spider down on each bald patch, forcing a bite. The lesions that formedwere similar to those found in human victims.

Published on January 12, 2012 09:00

January 11, 2012

Hobo Spiders, Part 2 of 4

Camel Spiders

Camel Spiders(The Book of Deadly Animals hits the US later this month. As with the recent UK release of the book, I'm going to celebrate by running here an expanded version of a story from the book.)

It's hard to say how many people have been hurt by hobospiders, because spider bites are remarkably difficult to diagnose. Part of theproblem is that they often don't hurt enough at first to draw any notice. Evenin the case of bites that develop serious symptoms like the ones I describedabove, it is unusual for the victim to bring in the guilty spider. Often thesupposed spider bite is just a wound or sore of unknown origin. It's beenestimated that 80% of the so-called spider bites physicians treat are reallysomething else entirely—the bites of lice, fleas, or ticks; the symptoms ofdiseases like Lyme disease and tularemia; strep or staph infections developingaround minor scratches. Even eczema or a too-vigorously scratched mosquito bitemay cast aspersions on some innocent arachnid. When several Americans came downwith skin lesions in 2001, symptoms eventually attributed to anthrax spread byterrorists, doctors first suspected brown recluse spiders.

Why do spiders so often get the blame? Part of the answerseems to lie in arachnophobia. People who notice a sore and, separately, aspider in the house may jump to the wrong conclusion. Serious arachnophobesoften report the feeling, which they themselves may recognize as irrational,that spiders are malicious, trying to frighten and harm human victims. Evenpeople without a full-blown phobia will sometimes fall into this way ofthinking. In fact, most spiders, if they're capable of biting people at all,only bite in defense of self, eggs, or territory, but many people aren't awareof, or even interested in, that fact.

Another source of confusion is folklore. Stories of venomousarthropods circulate so frequently that scientists tend to dismiss them out ofhand. Around 2001, I received emails warning of "blush spiders," tinybut deadly red spiders that hide under the seats of toilets on airplanes readyto bite the unwary traveler on his or her most sensitive parts. There'sactually no such thing as a blush spider. Its "scientific name," Arachnius gluteus, which would seem totranslate into something like "butt spider," is an easy tip-off.

In 2004, I received anxious queries about "camelspiders," accompanied by a shocking photo of a massively-fanged monster aslong as a man's leg. The camel spider, it was said, habitually runs along undercamels, leaping up to feast on the flesh of their bellies. Its venom was saidto dissolve flesh rapidly. It was claimed that these creatures represented adeadly menace to soldiers at war in Iraq. In fact, camel spiders are harmless,though scary-looking. They are known variously as sunspiders and windscorpions,but are really a little-known arachnid family unto themselves, the solfugids.The largest solfugids in the world are about the size of a woman's hand, whichis certainly awe-inspiring, but a mere fraction as large as the trick ofperspective in the well-circulated internet photo suggests. Solfugids don'tbite people—their mouthparts aren't hinged the right way, so it's the nextthing to physically impossible—and they don't pack toxin. Since their fangs areso massive for their size (proportionally the largest in the animal kingdom), theyrely on mechanical injury to kill their prey, not venom.

These are only two examples of the folkloric nonsense aboutarachnids constantly in circulation. Another bit, from the Middle Ages, heldthat spiders spread the Black Death that killed a third of the population ofEurope. It's been suggested that this myth underlies the arachnophobia soprevalent in Western culture.

With such drivel perpetually in the air, it's not surprisingthat many scientists and doctors have dismissed more credible claims out ofhand.

Next: Shaved Rabbits

Published on January 11, 2012 09:00

January 10, 2012

Hobo Spiders, Part 1 of 4

Tobias Mercer/Creative Commons

Tobias Mercer/Creative Commons(The Book of Deadly Animals hits the US later thismonth. As with the recent UK release of the book, I'm going to celebrate byrunning here an expanded version of a story from the book.)

January, 1988. A 56-year-old woman from Spokane feltsomething bite her on the thigh. She came down with a migraine-style headacheand nausea. Her thinking became addled. In the coming days, a patch of deadtissue sloughed from the spot where she'd been bitten. It was perhaps two weeksbefore she sought help, and by then it was too late. She was bleeding from theorifices, even from the ears. Doctors found her blood deficient in severalbasic components. Her marrow had stopped making red blood cells. Havinglingered in the hospital for several weeks, the woman died of internalbleeding.

There were other cases.

November, 1995. In a suburb of Portland, Oregon, aten-year-old boy woke with a pair of bites on his leg. The wounds swelled, grewhot, blistered. Dead tissue dropped away. A week after the bites, his leg wasswollen and red. He suffered fever, nausea, and debilitating headaches. After amonth, the pain of the wounds was mostly gone, but a bruise-like patch of blueremained on his leg. The headaches lasted four months.

October, 1992. A 42-year old woman from Bingham County,Idaho, felt the burning bite of a spider on her ankle. She, too, came down witha headache and nausea, as well as dizziness. The bite blistered and burst,leaving an open wound that continued to grow. After ten weeks the crater wasbig enough to accommodate two thumbs and ringed with black flesh; it was stillgrowing. Eventually, more than two years after the bite, the wound had healedinto a sizable scar, beneath which the veins were clotted. The woman's abilityto walk and stand remained impaired, limiting her job options.

The spider she had found crushed within her clothing was ahobo spider, Tegenaria agrestis, amember of the family Agelinidae.

*

The Agelinidae are hairy, brown or gray, often big enough tostraddle the face of a pocket watch. They build flat webs with a sort ofbilliard pocket at one corner in which the spider lies at her ease to awaitprey. They're common as cliches, found in temperate places all over the world,in about 38 genera and 500 species. In England a type of agelinid, the lesserhouse spider (Tegenaria domestica),is found behind books on the shelf, its thick web tearing when a volume isconsulted. In the American Southwest I've often seen a gray agelinid with longblack stripes. Its abdomen is typically an ovoid tight and ripe as a Septemberplum. This species has eyes that shine like scattered emeralds in the dark, andits webs lie about on the ground cover like silk handkerchiefs—crisply white atfirst, but progressively dirtier with time and use. I have seen these spidersrush out of the funnel when an insect lands on the handkerchief. The spidercloses on its victim like a hirsute hand. It delivers what looks incongruouslylike a kiss to the prey's head, whereupon the prey ceases to struggle withshocking suddenness.

Soon the spider drags his prey into the funnel, where it is hardfor a nosy biped to watch. Usually all I can see are dark masses and anoccasional shadowy scrabbling of legs. What happens, of course, is that thespider injects its digesting venom into the prey, breaking its innards intosoup before sucking them down. The next day I often find a few insect legslittering the edge of the handkerchief.

Parker Grice

Parker GriceIn the upper Midwest, where the outdoors is coldlyinhospitable to spiders several months a year, I have often noted anotherspecies of agelinid residing in basements. Anything left on the basement floorundisturbed long enough is likely to harbor a mass like a frayed handful ofcotton balls. In one such web I noticed a hummock shaped like a human graveformed over the body of some black creature. This carcass was apparently toomuch trouble to drag over the web's edge. The spider had simply built over it.These northern agelinids are brown and rapid. I've found in their webscreatures as diverse as millipedes and mosquitoes. I touched one web,delicately as I could, and saw the spider heave itself out of its funnel-shapedretreat and immediately collapse back into it, so fast I could hardly have toldwhat it was if I hadn't already known. It reminded me of horror stories told byarachnophobes, about spiders emerging from bathtub drains. I withdrew my fingerwith considerable haste.

The web felt like cloth made of human hair. It didn't stickto me. This is typical of the agelinidae, including the hobo spider—their websaren't gluey, but depend on their deceptive surface to snare insects. Whatseems a solid, smooth place to land is actually a layered network of filaments.Most insects lack the foot-gear to negotiate this snare. Their feet fallbetween the strands, their claws snagging and delaying their escape long enoughfor the spider to seize them. The spider itself walks on the strands byclasping them between claws that oppose each other, much like the opposablethumb-and-finger arrangement of a primate.

The hobo spider shares the web style and habits of thesekinsmen. It is clad in brown herringbone and its body is typically just shortenough to fit on a Lincoln penny. Its genus name means mat-weaver; the speciesname suggests the agrarian lifestyle the species leads in Europe. But in NorthAmerica the hobo spider has taken up an urban lifestyle and made its presenceknown to the human community in ways its European experience never suggested.

Next:Myths and Fears

Published on January 10, 2012 08:30