Gordon Grice's Blog, page 66

February 5, 2012

Animal Control Workers Make Super Bowl Sweep

"For what seems an eternity (at least to those of us who would rather undergo a transorbital leukotomy with an ice pick than the protracted brain death of pregame hype), our cultural conversation is preempted by a live feed from the jock unconscious of Team America," writes Mark Dery in his new book I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts: Drive-by Essays on American Dread, American Dreams

. "The chattering class act as if we're one big happy congregation gathered in solemn veneration of the Gipper's jockstrap." Remarks like this are only one reason why I'm a fan of Dery's essays. Readers of this blog will remember Dery as the author of a startling account of Jerusalem crickets that ran here a while back.

. "The chattering class act as if we're one big happy congregation gathered in solemn veneration of the Gipper's jockstrap." Remarks like this are only one reason why I'm a fan of Dery's essays. Readers of this blog will remember Dery as the author of a startling account of Jerusalem crickets that ran here a while back. Anyway, for those who are interested in the Super Bowl, rest assured that the animal attack situation in Indianapolis is well in hand:

Animal Control Workers Make Super Bowl Sweep - Indiana News Story - WRTV Indianapolis:

"INDIANAPOLIS -- Animal control officers combed Indianapolis streets for dangerous dogs ahead of Super Bowl week to prevent bites, attacks and traffic crashes during the festivities. Indianapolis Animal Care and Control workers said public safety is their first priority and they're targeting neighborhoods surrounding Lucas Oil Stadium."

Published on February 05, 2012 09:00

February 4, 2012

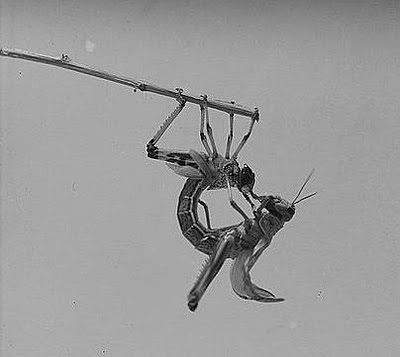

Purse Web Spider

I've always been interested in this species, though my range happens not to overlap its. I learned about it from books when I was a child, and was immediately fascinated by its habit of living inside a sort of silken sock. When an insect treads on the sock, the spider bites through the silk for the kill. Perhaps that's why the spider needs that massive set of chelicerae.

Incidentally, the purse web spider is altogether more civilized about romance than certain widow spiders frequently mentioned here. Male and female often cohabit peacefully. It's only after the male dies of old age that the female eats him.

Video by Nik Nimbus:

Further info (and spectacular photos) on Nik's blog.

Incidentally, the purse web spider is altogether more civilized about romance than certain widow spiders frequently mentioned here. Male and female often cohabit peacefully. It's only after the male dies of old age that the female eats him.

Video by Nik Nimbus:

Further info (and spectacular photos) on Nik's blog.

Published on February 04, 2012 09:00

February 3, 2012

Grice on The Grey (from Wall Street Journal's Speakeasy)

Are Wolves Really as Dangerous as They Are in 'The Grey'? - Speakeasy - WSJ: "How afraid should we be of wolves? Judging by the new film, "The Grey," very. But is that really true? Gordon Grice, the author of "The Book of Deadly Animals," sets the record straight in an essay in Q&A form."

Published on February 03, 2012 11:06

Fungal Interlude #1

Published on February 03, 2012 09:00

February 2, 2012

India: Monkey Attacks Four

A monkey, having already attacked three others, has now bitten the toe off an elderly woman.

A monkey, having already attacked three others, has now bitten the toe off an elderly woman. 60-year-old gets 60 stitches after monkey attack - Times Of India:

"Locals said that the monkey has been running amok in the area and has attacked four people in the past few days. In fact, an NRG woman had to postpone her departure for the UK after she was attacked by the monkey. Dipti said that they have alerted the zoo authorities, who, however, have not been catch the wayward simian."

Thanks to Croconut for the news tip.

Published on February 02, 2012 09:00

February 1, 2012

Hunger on the Wing (Conclusion)

One afternoon I looked in on the six or seven grasshoppers Ihad in separate jars and found that they had done something interesting. Wetorange strands, about the thickness and texture of a braided bootlace, lay intheir jars. A day or two later, I saw one of my captives in the act ofproducing such a strand. It pressed its hind end against the floor of the jarand arched its back, as if exerting downward pressure, and an orange strandsqueezed out from the rear, like toothpaste from a tube. This strand lookedslimier and smoother than the others I'd seen but was recognizably the samething. By the next day it had dried to look exactly like the other hoppers'strands, the pattern of its texture emerging as it dried. A day later it wasdry enough to see that what had appeared to be individual strands woventogether were merely dozens of pieces, shaped like sesame seeds, arranged in anorderly overlap—eggs, of course.

In Missouri in the 1870s, the egg masses of Rocky Mountainlocusts lay so thick in the beds of rivers and creeks that authorities offereda five-dollar bounty per bushel of them. This species, the only grasshopper inNorth America that typically shifted into the locust phase, had swarmed forhundreds of years, as proved by layers of locusts in glaciers dated at around750 years old. Presumably, they had swarmed for millennia before that. Butaround 1880 the swarms abruptly ceased, and the species went extinct. The lastlive specimens were collected in 1902.

No one knows why the Rocky Mountain grasshopper vanished,but changes in habitat are the most likely reason. In the late 19th century,the bison was virtually exterminated, as were the native peoples. Settlersdrastically reduced the numbers of beaver in the Rocky Mountains, removing animportant control on flooding. Cattle brought in by ranchers grazed andtrampled the riversides, and farmers plowed up their fertile soil. To fight offthe locusts, farmers tried all sorts of control measures, from contraptionscalled "hopperdozers" and controlled fires to fasting and prayer.What actually worked was to carry on farming. Plowing devastated the RockyMountain locust population, as did the planting of exotic trees, which broughtin many new predatory birds.

Hundreds of other grasshopper species thrived despite, oreven because of, these habitat changes. But according to Jeff Lockwood, anentomologist at the University of Wyoming, the Rocky Mountain grasshopper'snesting habits made it particularly vulnerable. (Many species prefer grassyhillsides for nesting sites.) The Rocky Mountain locust's boom-and-bustpopulation cycles also put it at risk. Despite the vast areas attacked byswarms—from Manitoba to Texas and from Wisconsin almost to the West Coast—thelocust's home base, the area where it could always be found in plague years aswell as other times, was a much smaller area in the northern Rockies.European-American settlement there quickly dispatched the species. It's theonly known case of a pest species exterminated by human action, and it was anaccident.

The extinction went unnoticed for a few decades—that such afecund creature could abruptly vanish was counterintuitive—and unmourned. Thefocus of 19th-century science was killing pests, not appreciating them. Westill don't know what effect the extinction has had. The swarms causedwidespread nutrient recycling and large-scale habitat disruption. CharlesBomar, an insect ecologist at the University of Wisconsin at Stout, hasspeculated that they served as some sort of cyclic ground clearing, much likeforest fires. But specific effects are difficult to substantiate, and no onehas proved any related extinctions.

Even the basic facts are in dispute. Daniel Otte, thecurator of entomology at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia,suggests the Rocky Mountain locust is not extinct at all but has simplyrefrained from swarming in recent times, perhaps because of encroachingagriculture. Otte points out that almost no one can distinguish closely relatedgrasshopper species by sight. In fact, the integrity of the Rocky Mountainlocust, Melanoplus spretus, as a distinct species has only recently beendemonstrated through genetic analysis. The characteristics that distinguish M.spretus from its close, and still living, cousin Melanoplussanguinipes (the migratory grasshopper) are its proportions. Identifyingan M. spretus involves taking its measurements—the length of thevarious leg segments, for example—and comparing them with published figuresderived from statistical analysis. To complicate this problem, no one is surewhat the solitary phase of M. spretus looked like. The very idea ofgrasshoppers shifting phases came about just as M. spretus was dyingout. It's possible, Otte says, that Rocky Mountain locusts are nibbling at yourlawn right now, unrecognized. More likely, they're hidden in remote rivervalleys, reduced in number but still thriving.

This apparent extinction, far from creating a domino effectof further losses, may have created an opportunity for other grasshopperspecies. The red-legged grasshopper (Melanoplus femurrubrum), whichwas responsible for newsworthy outbreaks in Idaho in 2001, thrives on groundbroken by agriculture and other human endeavors. Its numbers have grown muchlarger since the extinction of its cousin. In 2002, patchy outbreaks ofclear-winged grasshoppers (Camnulla pellucida) in Colorado attaineddensities of 200 per square yard; a tenth of this number is considered a dangerto crops. Scientists have had some success in developing toxins andparasite-laden baits to combat grasshopper outbreaks. But applying pesticideson broad stretches of land has rarely proved cost-effective. Some pesticidesseem to make future outbreaks worse, because the predator and parasitepopulations they affect don't recover from the poisoning as fast as thegrasshoppers do.

Even though existing North American grasshopper speciesdon't migrate as readily as the Rocky Mountain locust did, some of them doswarm in less dramatic migrations. And their swarming potential may have moreto do with circumstances than with any inherent limitations. Bomar suggeststhese other species, especially the red-legged grasshopper and the migratorygrasshopper, are stepping into the niche the Rocky Mountain locust vacated. Hissuggestion brings back uncomfortable memories of the giant I found in mydriveway. "The potential for swarms is there," Bomar says."Eventually, one of these micropopulations is going to move out."He's intrigued by the scientific opportunity such an event would present. Forthe rest of us, it may be the return of an ancestral nightmare.

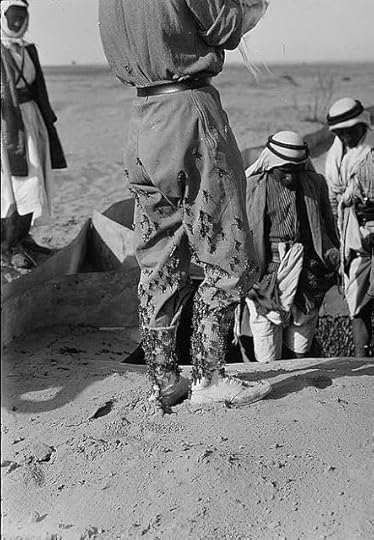

African locusts herded into a trap

African locusts herded into a trap A pitful awaiting immolation

A pitful awaiting immolation

Published on February 01, 2012 09:00

January 31, 2012

Hunger on the Wing (Part 2 of 3)

The most vivid firsthand account of swarm behavior is surelythat of Laura Ingalls Wilder, the children's writer who chronicled the life ofher family on the American frontier. By 1874 Wilder's restless father had movedthe family to a homestead near Walnut Grove, Minnesota. Wilder vividly paintsthe heat of that summer: The edge of the prairie "seemed to crawl like asnake" with heat shimmer, and the pine boards of buildings dripped theirviscous sweat. The family's wheat crop, which promised to yield generously, washead-high. Then a cloud dimmed the day, moving in without wind. Its individualparticles glittered. The falling insects sounded like a hailstorm, and thissound was succeeded by the multitudes chewing (like the working of thousands ofscissor blades, some witnesses said). Prairie grasses and wheat and oat cropsvanished; beets, beans, potatoes, carrots, and corn were razed; willow and plumtrees were shorn. (Although the Ingalls family didn't grow these crops, othersnoticed the insects preferred to start with tobacco and onions when these wereavailable.) "Not a green thing was in sight anywhere" after a fewdays, Wilder concludes, echoing the Book of Exodus.

Only the family's chickens benefited, snapping up thewindfall of easy prey. (Some writers of the period noted that the chickens tookon the flavor of grasshoppers, and that they and their eggs became inedible.Others wrote that the grasshoppers themselves were edible, though the Ingallsfamily does not seem to have taken an interest in this option.) The family fellon hard times, and at night they could hardly sleep for the sensation ofcrawling on their skin. On Sunday they arrived at church with their bestclothes crawling with grasshoppers and stained with their brown spittle. Themeager creek thickened with scum, and the land twitched with dust devils. Thecow's milk went bitter and nearly dried up.

Today's American infestations are minor compared with swarmslike those, but they still devastate wide areas from the Pacific Northwest tothe Great Plains. About 2 million acres of Colorado have been eligible fortreatment against grasshoppers in a single year, and it is not uncommon forseveral counties at a time to be affected by infestations. In an ordinaryseason, grasshoppers eat about 20 percent of the fodder on rangeland; in areasof infestation, the percentage can increase to 100, affecting millions of acresat $5 to $10 per acre. On cropland, the devastation is even greater.

Although the Rocky Mountain locust, the species that wreakedhavoc here in the 19th century, does seem to have disappeared, its ecologicalniche may be only temporarily vacant.

At rest, the red-legged grasshopper, a close cousin of theRocky Mountain locust, looks vaguely mechanical. Two immense eyes take up thesides of its head. Roughly between these are three smaller eyes and a pair ofshort antennae. The hard, yellow-green underside of its thorax is marked withdeep indentations that resemble smiley faces doubled and distorted in mirrors.The abdomen is segmented. The rear of it ends in four blunt appendages closedtogether like pinching fingers. When the insect takes flight, its vitality isrevealed. The camouflaged forewings open to show the vivid hind wings, whichflutter loudly and too fast to be seen distinctly. The specialized hind leg isa marvel of complexity. It possesses sensory equipment as well as a comblike projectionused by the male to coax music from his wings, and its muscles are powerfulenough to accomplish some of the most impressive leaps, proportionallyspeaking, in the animal kingdom.

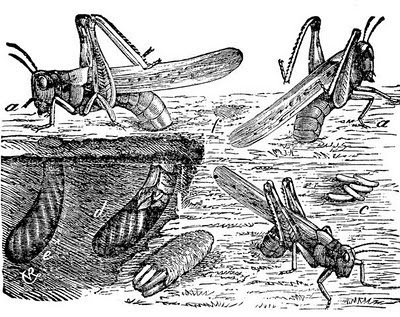

Rocky Mountain locusts laying eggs in topsoil

Rocky Mountain locusts laying eggs in topsoilMuch of the grasshopper's insides are taken up byreproductive equipment. The female's ovaries produce rows and rows of eggs,which are attached by stemlike parts to each other. The effect is somethinglike an orderly bunch of grapes, lined up mostly in neat rows, and glisteningwith moisture. However, the naked eye is impressed mainly by the fat blackstrand of digestive tract. Narrower in spots and girdled with knotty, fibrous projectionsnear the middle, it is essentially a tube. The dark color is that of chewedvegetation. At any given time, a substantial proportion of the grasshopper'sbody weight is its unconverted food. When a grasshopper is eaten by a mantis,the mantis typically eats around this unattractive vegetation. It is leftholding the digestive tract, which resembles the stick at the center of a corndog.

That summer in Oklahoma, I caught some grasshoppers in jarsand fed them on weeds and grasses. They ate avidly, leaving nothing of myofferings. Their mouths had toothed jaws with multiple points of articulation,a complex arrangement that appeared to constitute two or three mouths workingat once. In fact, this equipment allowed them to chew both vertically andhorizontally. Typically, they chewed along a blade of grass, creeping up theblade several inches before going deeper. Or they chewed a hole through theblade, then expanded the hole until the blade was cut in two and it collapsed.

The jars didn't suit them: They were heavy, humid creatures,and in a day or two the glass was fogged with condensation, the bottom of thejar laden with their conical black feces and their spit. They died off quickly,even when placed in more commodious accommodations. I tossed a grasshopper intothe web of a black widow spider, assuming the spider would dispatch it quickly.Instead, the grasshopper's energetic struggles wrenched it loose from the web,though at the cost of a hind leg. I repeated this experiment with a differentindividual. This time the grasshopper's leaps freed it easily, and furtherleaping knocked the spider from its web. The spider lay on its back, kickingfrantically, as the grasshopper chewed its front leg.

It's such hunger that drives a locust swarm. A single desertlocust can eat its own weight in a day. Multiplied by a billion, this hungermay be the most demanding our planet has known. The mechanisms behind thebehavioral change from solitary grasshopper to swarming locust are not wellunderstood. In the laboratory, scientists have been able to provokegrasshoppers into a phase shift by pelting them with wads of paper for hours onend. This result suggests that the jostling the grasshoppers experience in agroup prompts the phase shift. Stephen Simpson of the University of Oxford has locatedthe hardwiring for this mechanism more precisely on the insects' hind legs. Aspot there (which Simpson calls "the G-spot—G for gregarization") isthe trigger that somehow provokes morphological changes. (Other research, nowlargely disproved, pointed toward pheromones found in the feces, most likelyproduced by gut-dwelling bacteria, as the stimulus to change.) It may be thatmultiple cues are involved, and perhaps different locust species use differentcues.

Population explosions occur in various animal species, fromrabbits to mayflies. Vast migrations occur in creatures as diverse as monarchbutterflies and wildebeests. But the phase shift and swarming of grasshoppersappears to be unique. It may provide a way to survive and reproduce when foodsupplies dwindle. In Africa, the desert locust's eggs can lie dormant in aridsoil for several years until rain triggers their hatching. The hatchling nymphsthrive on the brief lushness that desert rains bring. When they've devouredeverything in an oasis, they swarm to reach green regions beyond the desert. Inthe case of the Rocky Mountain locust, however, the swarming is moremysterious. These locusts never seemed to establish permanent populationsbeyond their home base in the Rockies.

When the young of swarming locusts hatch, they, too, areswarming locusts. The ability of grasshoppers to inherit traits their parentsacquired was once a puzzle, for it seems to bypass the gradual genetic changethat the theory of evolution predicts. Some entomologists describe thisphenomenon as "cultural": The mother locust supplies her eggs with aheavier dose of nutrients and a chemical—called a maternal gregarizingagent—that encourage her offspring to develop toward the gregarious end of itspotential. The environment into which it hatches (the jostling swarm itself)also constitutes a cultural influence. Such nongenetic inheritance is notunique; it has been observed in human populations when, for example,consistently good nutrition over several generations prompts an increase inaverage stature. The offspring of locusts born in a subsequent season may ormay not develop into locusts; crowding is the deciding factor.

Published on January 31, 2012 09:00

Pythons Prey on People and Other Mammals

A recent report in PNAS claims that reticulate pythons regularly prey on the Agta people of the Philippines. In The Book of Deadly Animals, I told of constricting snakes attacking and even killing people, but I questioned whether that actually happens in the wild. I also questioned whether snakes actually prey on people; in all the captive attacks I was able to discover, death was not followed by consumption. These scientists believe they have proof of both wild attacks and predation. (Thanks to Chuck and Croconut for the news tips.)

Today's news is full of pythons. First, new documentation that escaped constrictors (mostly Burmese pythons) are having an impact on the Everglades ecosystem:

BBC News - Pythons linked to Florida Everglades mammal decline:

"They found that observations of raccoons and opossums had dropped by about 99%. There had been a 94.1% fall in observations of white-tailed deer and an 87.5% decrease in sightings of bobcats.

No rabbits or foxes were seen during the more recent survey; rabbits were among the most common mammals in the roadkill survey between 1993 and 1999.

The majority of these species have been documented in the diet of pythons found in the Everglades National Park. Indeed, raccoons and oppossums often forage at the water's edge, where they are vulnerable to ambush by pythons."

Meanwhile, in Uganda, wildlife authorities and police teamed up to capture pythons suspected of being used in witchcraft ceremonies. I haven't encountered such credulity since my last visit to West Memphis. Investigators found no pythons, though they did bag three rats.

Published on January 31, 2012 06:42

January 30, 2012

Hunger on the Wing (Part 1 of 3)

An African sky filled with locusts

An African sky filled with locustsHere's another story from The Book of Deadly Animals. (Thenew US paperback version hits book store shelves tomorrow; or order it onlinehere.) In the book, I didn't have room for the whole story, since there weremore than 900 other animals to talk about. This longer version first appearedin Discover.

*

One summer in the Oklahoma panhandle the grasshoppers wereeverywhere. Every patch of weeds along the alley would erupt like a pan ofpopping corn if I set foot in it. When we drove the highway, we inadvertently slaughtereddozens. The collisions speckled our windshield with hemolymph. Their wings,coffee-colored fans striped with yellow at the outer edges, lodged in ourwipers and fluttered in the onrushing air. Sometimes an entire grasshopper, ormost of one, would lodge there as well, struggling to get free as the wind toreit to tatters.

They could be found in unaccustomed places that summer. Forseveral mornings running I saw two or three swimming in the dog's water dish.The rosebushes took on the riddled look of lace, as though the grasshoppers hadtasted the leaves and found them unappealing but serviceable. In the country,the cedar posts of barbed wire fences would seem at a glance to be shimmeringwith heat, like a water mirage on the highway, but a second glance would showthe effect was not an optical illusion. The posts were simply crawling withgrasshoppers moving up or down for no apparent reason. They seemed to be movingwith great caution, edging past each other. When a stationary grasshopper got bumped,it would draw its legs in tighter and shift its footing, like a personuncomfortable on a crowded bus.

Then there was the jackrabbit. We found it beside a dirtroad on the way to the mailbox. It was dead, probably road-killed. Grasshopperswere thick in the weeds and grass along that road, and dozens clustered on thecarcass. When someone poked at it experimentally, a few of the hoppers jumpedoff and opened their wings and were carried away by the wind. Others crawledoff sluggishly. Some stayed put. With the carcass now more exposed, we couldsee that it was bald in patches, and that its hide was wounded in shallowdivots, as if it had been hit all over with buckshot that failed to penetrate.It seemed that the grasshoppers had been eating it.

As the season wore on, the grasshoppers grew absurdly thick.Among the metallic green ones there were others, some yellow and spotted,others a brighter green. All these I was familiar with, though I had never madeany particular study of them. But I began to see things utterly new to me. Onegrasshopper was black and flecked with gray, like burned charcoal. Another wasblack but flecked with a Tabasco red. This variety has been explained to methus: In outbreaks, grasshoppers are so plentiful that they overwhelm theirusual predators, offering them more food than they can use. Other grasshopperspecies, rare enough to go unnoticed most of the time, get relief frompredators in this circumstance, and therefore are more likely to be around forpeople to notice.

Other things seemed different too—there were a great manylarge grasshoppers, thick as a lipstick. One morning on my driveway I found thelargest specimen I had ever seen, a yellowish creature longer than a soda can.It was dead—a fact that gave me some comfort. Streams of black ants led up toits carcass. Their presence was the first thing that convinced me I was seeinga once-living creature rather than a toy. I turned it belly-up with a stick.Its head and thorax were intact, but its abdomen was riddled with holes. I hadnot seen this damage at first because its long wings concealed it from above.Through the holes I glimpsed ants working at the grasshopper's half-hollowhull.

What I've been describing is an infestation, a localizedpopulation suddenly grown orders of magnitude beyond its usual numbers. Thecauses are not thoroughly understood. In the United States, hot, dry weatherhas something to do with it—the heat lets grasshoppers grow faster, and thedryness discourages the fungi that would otherwise check the population'sgrowth.

Swarms of locusts—giant flying species of grasshoppers—are atraveling variation on this phenomenon. They dominate a wide swath of this planetalmost every year. Moving in groups of millions, the locusts migrate over greatstretches of territory, settling down periodically to eat every bit ofvegetable matter in sight. They are hunger on the wing.

In the United States migratory swarms of locusts arepresumed to be a thing of the past. But a locust is really just an oversizegrasshopper in a gregarious mood. When grasshoppers of certain species gatherin great numbers, they begin to change their behavior. Normally, they aresomewhat solitary. If forced together they seem uncomfortable, leaping awayfrom each other. But hunger often forces them together when a bumper crop ofgrasshoppers encounters a meager supply of food and they must compete for it.If the crowding persists, the younger insects begin to change. The changes varywith the species, but in general their bodies grow to massive size. Their wingsbecome clear and strong. Their colors shift dramatically—for example, fromgreen and yellow to solid black. Their proportions alter, their shapeessentially changing to accommodate flight. So profound is this change that scientistsin the past have mislabeled the two phases, solitary and gregarious, asdistinct species.

The creatures behave differently, too. They eat withshocking voracity. They whirl into the air in groups, forming swarm clouds. Theswarms fly long distances, disrupting ecosystems for hundreds of miles. In the1870s, one swarm was tracked from Montana to Texas, a distance of 1,500 miles.Polluted layers of glaciers high in the Rockies show that their flightsometimes takes them to altitudes beyond the normal range of grasshoppers. In1874 a Nebraska doctor used telegraphs to find the far edges of a swarm heobserved flying overhead, establishing that its area exceeded that of Colorado.Factoring in their rate and the depth of the swarm cloud, he arrived at anestimate of 12.5 trillion grasshoppers. The Guinness Book of World Records liststhis swarm as the "Greatest Concentration of Animals" yet observed.More rigorous methods were used on a swarm in Kenya in 1954, yielding thefigure of 10 billion grasshoppers in a swarm, which happened to be only one of50 swarms in that country at the time.

Published on January 30, 2012 09:00

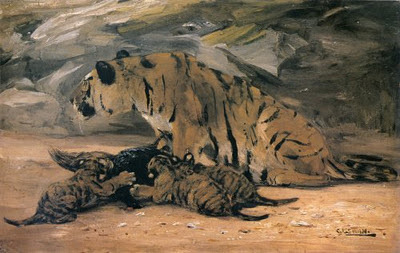

Tigress Kills Farmer

In rural India, officials are tracking a tiger that killed a farmer.

Killer tigress still at large in Patan Bori - Times Of India:

""The tigress continues to kill our animals, but the forest officials have not been able to track and capture her," said a villagers who lost his cow a few days ago.

When contacted, Chief Conservator of Forest Devendra Kumar confirmed the reports about tigress' attacks. "The tigress is attacking animals to teach hunting to her cubs," he said."

Published on January 30, 2012 08:30