Gordon Grice's Blog, page 22

January 10, 2015

Rust

Our move brought me over a lift-bridge in the middle of a rainy night. Tracy had taken the place and set up housekeeping, and now she was showing me the way home. Our sons were in the back, one talking, the other sleeping. The road curved into the moist dark. “I’ll bet you’re wondering what I got you into,” Tracy said.

But in the morning the place was sunshine and the chatter of finches. We were to live in a village in the upper Midwest. The front of our place was a busy and badly paved road; the back was a straggling wood. Winter nights, you’d be able to see all the way through the naked forest to the houses on the other side. But for now it was spring and I had the illusion of a wilderness.

The Eastern red cedar tree in our back yard looked bad—shaggy, wasted, a dandruff of gray decline mixed in with the healthier bluish-green needles. We had seen the cause already, in the form of little spiky galls hanging here and there like drab Christmas ornaments. Each of these ornaments was smaller than a golf ball and seemingly made of wood, which might make you think it was some healthy part of the tree. I picked one off. Each little spike was a spout: a hole surrounded by a sharp woody projection. The ball resisted pressure only as much as a fruit might. Carrying it to the cement walk, I crushed it under my heel. It wasn't difficult. Inside, the thing was pulpy and fibrous, its strands of vegetable matter radiating from a tight core. Its wet texture was like that of the new wood you can find under a tree's bark.

I knew this from my trip to bat country as cedar apple rust, a parasite with a provocative life cycle. On the leaves and fruit of apple trees, this fungus manifests itself as leathery patches of discoloration. On red cedar trees, it takes the form of these woody galls. The apple and cedar forms of this parasite are different stages of a single life cycle which involves both sexual and asexual spores.

To look at it, though, I wouldn't have recognized this sphere as alien to the tree, made as it was of the tree's own tissues. The tree itself makes the sphere, acting on instructions from the fungus, like a human body producing a tumorous mass at the command of rogue cells. My sons gathered a few and smashed them with a tenderizing mallet to examine their insides.

Rain revealed more. It rained for two or three days, a steady soak that had my sons whooping barefoot on the lawn. One day they were all excitement: "The parasite opened up!"

Indeed. All over the fifty-foot tree, the galls had effloresced. Through each spiky spout, a vivid orange tentacle projected. It seemed as if the tree had collided with a swarm of sea anemones.

I bent a bough down so the boys could see. My older son poked at one gall

and proclaimed it slimy. I tried its texture myself: wet gummy worms. Our gentlest touches marred them. I almost expected them to recoil.

*

It used to be said that a fungus was a sort of defective or degenerate plant, one that lacked chlorophyll and so could not make its own food. It was thus reduced to feeding off the work of others—grubbing in the soil to devour dead animals, fallen leaves, and damp wood.

Biologists know better now, partly because of advances in genetics. In the last few years, DNA sequencing has revealed strong evidence for all sorts of things we hardly could have suspected—that whales belong among the even-toed hoofed mammals, that dinosaurs and birds are more closely related to crocodiles than turtles are. The method behind this is to look for similar strings of DNA, then analyze them statistically. All life on earth comes from a common stock; the more dissimilar two life forms are genetically, the longer it's been since they diverged. By applying sophisticated mathematical models, geneticists can estimate how long it takes for certain kinds of differences to arise. By comparing these numbers, they can deduce how closely related different kinds of living things are.

But this re-evaluation of relationships goes deeper than the shifting of animals among orders. Our vision of life at the most basic levels has altered too; the kingdoms, the very fundaments of Linnaean biology, have had to be shifted about. The fungi comprise their own kingdom now. We understand, better than we did at least, what they are. Certain organisms we had called fungi because they were slimy and repulsive and because we didn't know where else to put them—the slime molds, for example—have been exiled from the kingdom. That is not too hard to take, because few of us encounter slime molds with any regularity.

What's harder to take is that fungi turn out to be our kinsmen. They are not plants at all; they are closest to the animals—to us.

*

We usually think of fungus as an unhealthy thing, a sign of disease. That's a slander, for parasitism is only one of the possibilities of fungi.

In the woods behind my house I find uncountable lichens. These are, as every high school student learns, symbiotes, a fungus paired with an alga or a similar life form. They are the surface I touch when I lay my hand on a fallen tree; they are the first flaky layer my handsaw bites through when I gather dead wood. When my sons climb to prospect for higher views, half their footholds are ledges of lichen or simple fungus.

I called them uncountable. This is only partly because they are numerous. The other reason I can't quantify them is that they lack integrity. The whole leeward side of a certain box elder tree is crusted with green: where does one lichen end and another begin?

Fungi are often colonial, rather than singular. A million fungal filaments in a patch of soil may be in communication of a sort, all of them sending strands toward a food source when one detects it. There is, of course, no brain, no central command, merely a shared purpose. If we consider one such aggregation a single individual, then the largest life forms we know are fungal: stretching for miles within the soil, their mass rivaling that of the blue whales or perhaps even the redwoods.

If the individuality we tend to think of as fundamental is lacking in the fungi, then so are the species boundaries. Lichens are only one kind of symbiosis; the fungi have many. One style, for example, is the mycorrhiza, a combination of fungi with the roots of a plant. The fungi reach where the plant cannot, bringing in minerals the plant needs; the plant shares the food it makes from light and water. Though most people are perhaps not familiar with this arrangement, it is the basis of life as we know it. At least 80% of plants cohabit in such a manner—some estimates go as high as 90. The boundaries are not exactly where we are accustomed to draw them, because, practically speaking, the average tree or weed or grass is not merely a plant, but a combination of plant and fungus.

It is not easy to grasp this, or to see it without benefit of excavation, dissection, and microscopy. But the signs are visible, if you look. Sometimes in wet weather I find an arc of mushrooms in my front yard. It is this arcing distribution that reveals hidden relationships, for the focus of the arc is a maple tree. The mushrooms are the genitals of fungi intimate with the tree. It is possible to trace its thicker roots, barely concealed in the dirt, to aggregations of mushrooms.

*

A moody morning after rain. The rusts had poured forth their tentacles again, but after a few hours the tentacles had withered to brown scraps. My oldest son and I decided to retrieve one of them for study. He held a slender branch taut while I cut. The shears met in the wet wood with a squeak and a snap; the branch sprang upward, leaving its severed extremity in my son's hands. He plucked the rust off it avidly.

We watered it in a jar and it revived. Overnight, new tendrils of orange slime pushed their way out through the colandered sphere. It did not need rain, then; any drenching would do.

The next stage of our inquiry was a white plastic cup. We had learned that the rust spreads orange spores while it's active. Looking over its gelatinous tentacles, I had no doubt our specimen was alive, but we made the experiment anyway. Into the little white cup it went with a fresh supply of water. In the morning, the water showed orange against the cup—its spores coloring the water like a weak dose of Tang.

For a few days, my sons were always bringing in bigger, juicier specimens of the rust, poking them with sticks, marveling at them. Then their interest dwindled, and I'd find week-old jars of the things on shelves and window sills, the tentacles half dissolved in the water, retaining only their color.

*

I always suspected we were cousins. The fungi don't move the way we do, but some of them, the most visible ones, grow so fast it seems a sign of animal life: the mushroom big as a human fist found on your lawn the day after a rain, for example. I have a vivid childhood memory: something smooth and white nesting in the grass, the size and shape of a chicken egg, hardboiled and peeled. It was not an egg, however: my dog evinced no interest in it. Something about it made me reticent to touch it. It had no smell, but something about it reminded me of dog feces, or perhaps merely the Platonic form of disgust. The weird notion that it was an eyeball crossed my mind, and I went so far as to turn it over with a twig, looking for an iris. It was this operation that revealed its true nature to me, for it tore open under the stick and revealed, first, the stringy origami I associated with the insides of some mushrooms. The other thing this tearing revealed was the smell, which had hitherto been undetectable, the smell of rotten flesh.

Or maybe their overnight appearances simply seem like a sinister kind of magic. Toadstools, elves.

*

It is not only the plants that live in symbiosis with fungi. We animals do it, too. We do not like to think of it, because we have for so long conceived of microbes as unclean things, as invaders. But of course we have always been symbionts, dependent on the microbes in our guts to digest our food. We have colonies of fungus inside us as well. A so-called yeast infection is really an imbalance. It is not a problem that the yeasts are in the human body—they always are. It's a problem that their numbers have, because of some teetering of the pH level, exceeded their usual bounds. It is a natural thing to share our bodies with them, and with all manner of other organisms. As a tree is not simply a tree, we are not simply what we think we are.

Which is not to exonerate them all. Plenty of fungi are pure parasites, and these have invaded almost every kind of life. There are specialized fungal parasites of single-celled diatoms and even of other fungi. And some of these cause serious harm. The rust on my cedar tree was bad for it; it must have been even worse for the apple trees in the neighborhood, for the leaves of the apple are slowly pierced through by the rust, until spore-shooting orange masts sprout from their undersides. The fruit of the apple, too, may be ruined, its hide marred by soft brown patches.

So, too, with the human form. There are fungi to make the feet and the testicles itch, fungi to discolor and deform the fingernails. And there are neighborly fungi content to live within us unobserved, but which will blossom, in the case of a ruined immune system, into devouring sores, inside and out. It is a common enough way for people with AIDS to die.

*

Two years have passed since the last time our cedar was dazzling in its orange jewelry. The next year we waited in vain for another blooming of that odd fungal life. We had trimmed them off where we could reach, hoping to save the tree, but it wasn't our earthbound efforts that drove them away. We could still see dozens of them higher up, dry and drab, refusing to bloom. This is the way of the rust. It persists on apple trees, but on a cedar it gives its life to the wind and leaves its old self to rot.

Our tree grows shaggier year by year, more patched with vanilla and auburn. Within the greenery that remains I can reach dozens of lifeless branches. A good yank is sure to be rewarded with the crack of dead wood, dry enough to burn. The whole tree is ugly now, truth to tell. It reminds me of nothing so much as the shaggy head of a neglected old man.

Not that I neglect it. I prune; I am doing what I can to save its life. But it is dying, I'm sure of it. When we walk beneath it, mosquitoes and blackflies come for us by the swarm.

Published on January 10, 2015 09:00

January 3, 2015

Jararaca

Creative Commons/Fernando Tatagiba

Creative Commons/Fernando TatagibaI was interested to find this encounter with a venomous South American pit viper in Arthur Conan Doyle's seminal dinosaur novel, The Lost World. As usual when writing about snakes, Doyle is vivid and convincing, if not entirely accurate.

The place seemed to be a favorite breeding-place of the Jaracaca snake, the most venomous and aggressive in South America. Again and again these horrible creatures came writhing and springing towards us across the surface of this putrid bog, and it was only by keeping our shot-guns for ever ready that we could feel safe from them. One funnel-shaped depression in the morass, of a livid green in color from some lichen which festered in it, will always remain as a nightmare memory in my mind. It seems to have been a special nest of these vermins, and the slopes were alive with them, all writhing in our direction, for it is a peculiarity of the Jaracaca that he will always attack man at first sight. There were too many for us to shoot, so we fairly took to our heels and ran until we were exhausted. I shall always remember as we looked back how far behind we could see the heads and necks of our horrible pursuers rising and falling amid the reeds.

I hadn't read The Lost World in years. I'd forgotten how good it is.

Published on January 03, 2015 09:00

December 27, 2014

Encounter with a Shark

A wildlife classic by Cleveland Moffett

(Moffett interviewed salvage divers for a book published in 1898.)

Timmans, whom I used to call the student diver, because of his keen observation and capacity for wonder, leaned against the step-ladder that reached down from hatch to cabin on the Dunderberg, and remarked, while the others listened: "I did a queer job of diving once down into the hold of a steamship, a National liner, that lay in her dock, blazing with electric lights, and dry as a bone. Just the same, I needed my suit when I got down into her—in fact, I wouldn't have lasted there very long without air from the pump."

"Some queer cargo?" suggested Atkinson.

"That's it. She was loaded with caustic soda, or whatever they make bleaching-powder of—barrels and barrels of it, with the heads broke in after a storm, and it wasn't good stuff to breathe, I can tell you. First they set men shoveling it out, with sponges in their mouths, against the dust and gases, but one man coughed so hard he tore something in his lungs or head and died. Then they sent for a diver—that was me—and I worked hours down there hoisting and shoveling, like I was at the bottom of the bay, only there was no water to carry the weight. Say, but wasn't that suit heavy, and when I looked out through my helmet-glasses it seemed as if I was digging through a snow-field, with such a terrible dazzle it made my eyes ache to look at it."

"I suppose you don't usually see much under water?" said I.

"Depends on what water it is," answered Timmans.

"All rivers around New York are black as ink twenty feet down," remarked Atkinson.

"I know they are," said Timmans, "but I've seen different rivers. When I was diving off the Kennebec's mouth, five miles southeast of the Seguin light (we were getting up the wreck of the Mary Lee), then, gentlemen, I looked through as beautiful clear water as you could find in a drug-store filter. Why, it reminded me of the West Indies. I could see plainly for, well, certainly seventy-five feet over swaying kelp-weed, eight feet high, with blood-red leaves as big as a barrel, all dotted over with black spots. There were acres and acres of it, swarming with rock-crabs and lobsters and all kinds of fish."

"Any sharks?" said I.

Hansen and Atkinson smiled, for this is a question always put to divers, who usually have to admit that they never even saw a shark. Not so Timmans.

"I had an experience with a shark," he answered gravely, "but it wasn't up in Maine. It was while we were trying to save a three-thousand-ton steamer of the Hamburg-American Packet Company, wrecked on a bar in the Magdalena River, United States of Colombia. I'd been working for days patching her keel, hung on a swinging shelf we'd lowered along her side, and every time I went down I saw swarms of red snappers and butterfish under my shelf, darting after the refuse I'd scrape off her plates; and there were big jewfish, too, and I used to harpoon 'em for the men to eat. In fact, I about kept our crew supplied with fresh fish that way. Well, on one particular day I noticed a sudden shadow against the light, and there was a shark sure enough; not such an enormous one, but twelve feet long anyhow—big enough to make me uneasy. He swam slowly around me, and then kept perfectly still, looking straight at me with his little wicked eyes. I didn't know what minute he might make a rush, so I caught up a hammer I was working with—it was my only weapon—and struck it against the steamer's iron side as hard as I could. You know a blow like that sounds louder under water than it does in the air, and it frightened the shark so he went off like a flash."

"Perhaps he wasn't hungry," laughed one of the crew.

"Not hungry? I'll tell you how hungry those sharks were. They'd swallow big chunks of pork, sir, nailed and wired to barrel heads, as fast as we could chuck 'em overboard; swallow nails, wire, barrel heads, and all, and then we'd haul 'em in by ropes, that did for fish-lines, only it took twenty or thirty men to do the hauling. And there were plenty of sharks 'round, only they never seemed to tackle a man in the suit."

"Some say it's the fire-light of the valve bubbles that scares sharks off," commented Atkinson. "I don't know what it is, but I know the bubbles shine something wonderful as you watch 'em boiling up out of your helmet."

Published on December 27, 2014 09:00

December 20, 2014

Animal Images by Brueghel

Animal Sketches Images by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, a 16th-century Flemish artist.

Animal Sketches Images by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, a 16th-century Flemish artist.  Two Monkeys

Two Monkeys Hunters in the Snow

Hunters in the Snow

Published on December 20, 2014 09:00

December 13, 2014

A Wasp with Weird Wings

Published on December 13, 2014 09:00

December 6, 2014

Some Bird Songs

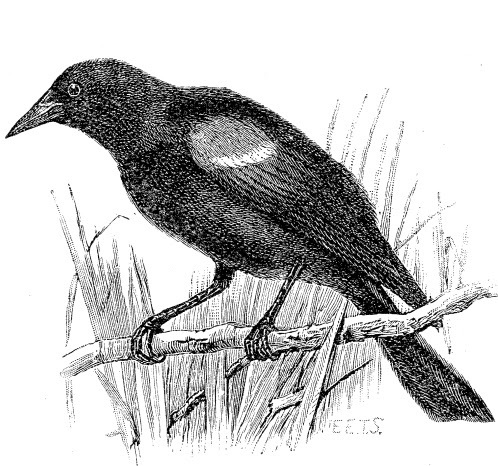

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a BlackbirdWallace Stevens

IAmong twenty snowy mountains,The only moving thingWas the eye of the blackbird.

III was of three minds,Like a treeIn which there are three blackbirds.

IIIThe blackbird whirled in the autumn winds.It was a small part of the pantomime.

IVA man and a womanAre one.A man and a woman and a blackbirdAre one.

VI do not know which to prefer,The beauty of inflectionsOr the beauty of innuendoes,The blackbird whistlingOr just after.

VIIcicles filled the long windowWith barbaric glass.The shadow of the blackbirdCrossed it, to and fro.The moodTraced in the shadowAn indecipherable cause.

VIIO thin men of Haddam,Why do you imagine golden birds?Do you not see how the blackbirdWalks around the feetOf the women about you?

VIIII know noble accentsAnd lucid, inescapable rhythms;But I know, too,That the blackbird is involvedIn what I know.

IXWhen the blackbird flew out of sight,It marked the edgeOf one of many circles.

XAt the sight of blackbirdsFlying in a green light,Even the bawds of euphonyWould cry out sharply.

XIHe rode over ConnecticutIn a glass coach.Once, a fear pierced him,In that he mistookThe shadow of his equipageFor blackbirds.

XIIThe river is moving.The blackbird must be flying.

XIIIIt was evening all afternoon.It was snowingAnd it was going to snow.The blackbird satIn the cedar-limbs.

Bird Music Transcribed in SyllablesGilbert H. Trafton

Red-winged blackbird: kong-quer-ree, or o-ka-lee, or gug-lug-lee.Maryland yellow-throat: witchity, witchity.Flicker: wick, wick, wick.Nuthatch: quank, quank, quank.Oven-bird: teacher, teacher, teacher.

A Bird Came Down the WalkEmily Dickinson

A Bird came down the Walk--He did not know I saw--He bit an Angleworm in halvesAnd ate the fellow, raw,

And then he drank a DewFrom a convenient Grass--And then hopped sidewise to the WallTo let a Beetle pass--

He glanced with rapid eyesThat hurried all around--They looked like frightened Beads, I thought--He stirred his Velvet Head

Like one in danger, Cautious,I offered him a CrumbAnd he unrolled his feathersAnd rowed him softer home--

Than Oars divide the Ocean,Too silver for a seam--Or Butterflies, off Banks of NoonLeap, plashless as they swim.

Published on December 06, 2014 09:00

November 29, 2014

A Python and Its Prey

Hairless

In a little desert town where I had business that fell through, I walked the streets. Downtown was crumbling brick and mortar, signs inviting civic pride and promising renovation. Another sign, felt-tip marker and stencil: “Exotic Snake Show.”

Inside I found a flight of cement steps, each step too narrow for my boots, each vertical face eroded as if by a waterfall. There were patches of whitewash on the mint green plaster walls. At the top of the stairs I found a room empty except for a table where a man stood with a cigar box full of cash.

“Where’s the show?” I said.

He nodded toward the next room, a huge loft. It was empty except for one corner where people stood around a few cages. “Just ask them and they’ll show you stuff,” the man said.

I paid two dollars and walked over to the cages. A young woman with moussed auburn hair sat in a folding chair. Wound around her arm was a thick strand of black patched with gold like puddles of liquid electricity.

The woman spoke the python’s name. When she turned to look at me I saw a lightning bolt painted on the left side of her face. I looked for the snake’s head, finally traced its body to an end which nuzzled under the woman’s shirt. The woman looked at me without expectation. She did not blink.

Someone called her from the other room. She held the snake out to me, extricating it from her clothes, gently raveling. I offered my hands. The python wrapped itself around my arm. The woman ran into the next room. The python was dry and light and alive, the power beneath its hide palpable.

A Chinese take-out carton on the table next to me scooted and rocked. Inside, wallowing in the oily remnants of fried noodles, six infant mice sniffed and twitched. They were pink and blind and naked and not unlike human fetuses. Another one lay in a cage, its side rising with its breath. A tiny python had found it. The lithe black tongue trickled in and out, caressing the pink mouse, tasting, taking its time.

Published on November 29, 2014 09:00

November 22, 2014

Kipling's Bear

The Truce of the BearBy Rudyard Kipling

Yearly, with tent and rifle, our careless white men goBy the Pass called Muttianee, to shoot in the vale below.Yearly by Muttianee he follows our white men in --Matun, the old blind beggar, bandaged from brow to chin.

Eyeless, noseless, and lipless -- toothless, broken of speech,Seeking a dole at the doorway he mumbles his tale to each;Over and over the story, ending as he began:"Make ye no truce with Adam-zad -- the Bear that walks like a Man!

"There was a flint in my musket -- pricked and primed was the pan,When I went hunting Adam-zad -- the Bear that stands like a Man.I looked my last on the timber, I looked my last on the snow,When I went hunting Adam-zad fifty summers ago!

"I knew his times and his seasons, as he knew mine, that fedBy night in the ripened maizefield and robbed my house of bread.I knew his strength and cunning, as he knew mine, that creptAt dawn to the crowded goat-pens and plundered while I slept.

"Up from his stony playground -- down from his well-digged lair --Out on the naked ridges ran Adam-zad the Bear --Groaning, grunting, and roaring, heavy with stolen meals,Two long marches to northward, and I was at his heels!

"Two long marches to northward, at the fall of the second night,I came on mine enemy Adam-zad all panting from his flight.There was a charge in the musket -- pricked and primed was the pan --My finger crooked on the trigger -- when he reared up like a man.

"Horrible, hairy, human, with paws like hands in prayer,Making his supplication rose Adam-zad the Bear!I looked at the swaying shoulders, at the paunch's swag and swing,And my heart was touched with pity for the monstrous, pleading thing.

"Touched with pity and wonder, I did not fire then . . .I have looked no more on women -- I have walked no more with men.Nearer he tottered and nearer, with paws like hands that pray --From brow to jaw that steel-shod paw, it ripped my face away!

"Sudden, silent, and savage, searing as flame the blow --Faceless I fell before his feet, fifty summers ago.I heard him grunt and chuckle -- I heard him pass to his den.He left me blind to the darkened years and the little mercy of men.

"Now ye go down in the morning with guns of the newer style,That load (I have felt) in the middle and range (I have heard) a mile?Luck to the white man's rifle, that shoots so fast and true,But -- pay, and I lift my bandage and show what the Bear can do!"

(Flesh like slag in the furnace, knobbed and withered and grey --Matun, the old blind beggar, he gives good worth for his pay.)"Rouse him at noon in the bushes, follow and press him hard --Not for his ragings and roarings flinch ye from Adam-zad.

"But (pay, and I put back the bandage) this is the time to fear,When he stands up like a tired man, tottering near and near;When he stands up as pleading, in wavering, man-brute guise,When he veils the hate and cunning of his little, swinish eyes;

"When he shows as seeking quarter, with paws like hands in prayerThat is the time of peril -- the time of the Truce of the Bear!"

Eyeless, noseless, and lipless, asking a dole at the door,Matun, the old blind beggar, he tells it o'er and o'er;Fumbling and feeling the rifles, warming his hands at the flame,Hearing our careless white men talk of the morrow's game;

Over and over the story, ending as he began: --

"There is no truce with Adam-zad, the Bear that looks like a Man!"

Thanks to James, who pointed me to this poem. I think it refers to a sloth bear (pictured above), but, when we discussed it on Facebook, others argued in favor of a moon bear. Literary critics have often seen the poem as a parable about Russia, which I guess makes the bear a Russian brown; but literary critics get on my nerves.

Published on November 22, 2014 09:00

November 15, 2014

Mindsuckers - National Geographic Magazine

A fascinating article in National Geographic tells about parasites who turn their victims into zombie bodyguards. My old friend the Ampulex wasp makes an appearance, as do cats, beavers, ladybugs, and more. (Thanks to Mom for the tip.)

Mindsuckers - National Geographic Magazine: " Across the natural world the same question arises again and again: Why would an organism do all it can to ensure its tormentor’s survival rather than fight for its own?"

For the strong of heart, here's a BBC video showing the jewel wasp in action, turning a cockroach into its slave:

Mindsuckers - National Geographic Magazine: " Across the natural world the same question arises again and again: Why would an organism do all it can to ensure its tormentor’s survival rather than fight for its own?"

For the strong of heart, here's a BBC video showing the jewel wasp in action, turning a cockroach into its slave:

Published on November 15, 2014 09:00

November 8, 2014

Double Day on the Prairie

The Parnell Prairie Preserve used to be the town dump, but it’s been rehabilitated, and now I walk on it as often as I can in the warm seasons. Its mowed paths wind through prairie grass and stands of birch and hills crowded with pines. One day my son Parker and I were walking there when we saw two riders on horseback. They stayed on the far side of the preserve, as if to give us our own space. I turned from them to see two half-grown deer bounding toward us around a bend. They moved like horses on a merry-go-round, up and down in perfect unison. I gasped at their nearness, and the sound made them notice us. Their heads jerked to direct their gazes toward us; the moist dark eyes held no expression, though I always seem to look for one; they bounded away off the path in a noisy haste. They had vanished in the grass before I could utter a sentence.

A face in the clouds

A face in the clouds“I barely saw them,” Parker said. “I was looking at the horses.”

Meanwhile, in the peripheral vision of my left eye, the two horses rolled by, making no sound, though their riders spoke to each other.

Everything seemed doubled that day—horse, rider, deer; there were even two of us. Before we left, we saw two skinks, one of them whipping along a fallen tree with nude white wood, the other spasming through the grass at the sound of our bipedal steps.

Photography by Parker Grice

Published on November 08, 2014 09:00