Gordon Grice's Blog, page 20

May 30, 2015

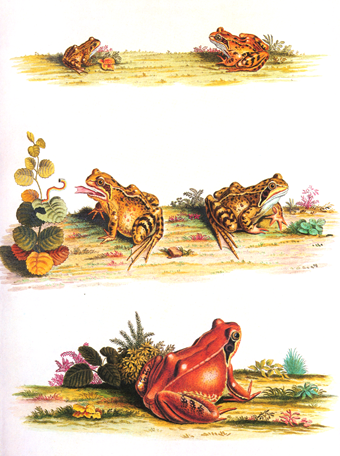

Antique Animal Illustrations by Rosenhof

August Johann Rösel von Rosenhof was an 18th-century German naturalist and artist. Modern biologists value his accuracy; I think his stuff looks cool.

Published on May 30, 2015 09:00

May 23, 2015

The White-Tailed Hornet

Beatriz Moisset/Creative Commons

Beatriz Moisset/Creative CommonsThe White-Tailed Hornet by Robert Frost

The white-tailed hornet lives in a balloon That floats against the ceiling of the woodshed. The exit he comes out at like a bullet Is like the pupil of a pointed gun. And having power to change his aim in flight, He comes out more unerring than a bullet. Verse could be written on the certainty With which he penetrates my best defense Of whirling hands and arms about the head To stab me in the sneeze-nerve of a nostril. Such is the instinct of it I allow. Yet how about the insect certainty That in the neighborhood of home and children Is such an execrable judge of motives As not to recognize in me the exception I like to think I am in everything—One who would never hang above a bookcase His Japanese crepe-paper globe for trophy? He stung me first and stung me afterward. He rolled me off the field head over heels And would not listen to my explanations.

That's when I went as visitor to his house. As visitor at my house he is better. Hawking for flies about the kitchen door, In at one door perhaps and out another, Trust him then not to put you in the wrong. He won't misunderstand your freest movements. Let him light on your skin unless you mind So many prickly grappling feet at once. He's after the domesticated fly To feed his thumping grubs as big as he is. Here he is at his best, but even here—I watched him where he swooped, he pounced, he struck;But what he found was just a nailhead. He struck a second time. Another nailhead. "Those are just nailheads. Those are fastened down." Then disconcerted and not unannoyed, He stooped and struck a little huckleberry The way a player curls around a football. "Wrong shape, wrong color, and wrong scent," I said. The huckleberry rolled him on his head. At last it was a fly. He shot and missed; And the fly circled round him in derision. But for the fly he might have made me think He had been at his poetry, comparing Nailhead with fly and fly with huckleberry: How like a fly, how very like a fly. But the real fly he missed would never do; The missed fly made me dangerously skeptic.

Won't this whole instinct matter bear revision? Won't almost any theory bear revision? To err is human, not to, animal. Or so we pay the compliment to instinct, Only too liberal of our compliment That really takes away instead of gives. Our worship, humor, conscientiousness Went long since to the dogs under the table. And served us right for having instituted Downward comparisons. As long on earth As our comparisons were stoutly upward With gods and angels, we were men at least, But little lower than the gods and angels. But once comparisons were yielded downward, Once we began to see our images Reflected in the mud and even dust, 'Twas disillusion upon disillusion. We were lost piecemeal to the animals, Like people thrown out to delay the wolves. Nothing but fallibility was left us, And this day's work made even that seem doubtful.

Published on May 23, 2015 09:00

May 16, 2015

Paintings by Schenck

Published on May 16, 2015 09:00

May 9, 2015

Nature Paintings by Winslow Homer

Black Bear and Canoe

Black Bear and Canoe Bridle Path, White Mountains

Bridle Path, White Mountains Fox Hunt

Fox Hunt Right and Left

Right and Left West Wind

West Wind Palm Trees, Nassau

Palm Trees, Nassau

Published on May 09, 2015 09:00

May 2, 2015

The Black Widow

(My most popular essay returns to this site after a lengthy absence.)

Angela Rotherman/Creative Commons

Angela Rotherman/Creative Commons

I hunt black widow spiders. When I find one, I capture it. I have found them in discarded car wheels and under railroad ties. I have found them in house foundations and cellars, in automotive shops and tool sheds, against fences and in cinder block walls. As a boy I used to lift the iron lids that guarded underground water meters, and there in the darkness of the meter-wells I would often see something round as a flensed human skull, glinting like chipped obsidian, scarred with a pair of crimson triangles that touched each other to form an hourglass: the widow as she looks in shadow. A quick stir with a stick would trap her for a few seconds in her own web, long enough for me to catch her in a jar. I have found widows on playground equipment, in a hospital, in the lair of a rattlesnake, and once on the bottom of the lawn chair I was sitting in as I looked at some widows I had captured elsewhere that day.

Sometimes I raise a generation or two in captivity. An egg sac hatches hundreds of pinpoint cannibals, each leaving a trail of gleaming light in the air, the group of them eventually producing a glimmering tangle in which most of them die, eaten by stronger sibs. Finally I separate the three or four survivors and feed them bigger game.

Once I let eleven egg sacs hatch out in a container about eighteen inches on a side, a tight wooden box with a sliding glass top. As I tried to move the box one day, I tripped. The lid slid off and I fell, hands first, into the mass of young widows. Most were still translucent newborns, their bodies a swirl of cream and brown . A few of the females were past their second molt; they had the beginnings of their blackness. Tangles of broken web clung to my forearms. The spiderlings felt like trickling water among my arm hairs.

I walked out into the open air and raised my arms into the stiff wind. The widows answered the wind with new strands of web and drifted away, their bodies gold in the afternoon sun. In about ten minutes my arms carried nothing but old web and the husks of spiderlings eaten by their sibs.

I have never been bitten.

*

The black widow has an ugly web. The orb weavers make those seemingly delicate nets that poets have traditionally used as symbols of imagination, order, and perfection. The sheet-web spiders weave crisp linens on grass and bushes. But the widow makes messy-looking tangles in the corners and bends of things and under logs and debris. Often the web is littered with leaves. Beneath it lie the husks of insect prey, their antennae stiff as gargoyle horns, cut loose and dropped; on them and the surrounding ground are splashes of the spider's white urine, which looks like bird guano and smells of ammonia even at a distance of several feet. This fetid material draws scavengers -- ants, crickets, roaches, and so on -- which become tangled in vertical strands of silk reaching from the ground to the main body of the web. Sometimes these vertical strands break and recoil, hoisting the new prey as if on a bungee cord. The widow comes down and, with a bicycling of the hind pair of legs, throws gummy silk onto the victim.

When the prey is seriously tangled but still struggling, the widow cautiously descends and bites the creature, usually on a leg joint. This bite pumps neurotoxin into the victim, paralyzing it; it remains alive but immobile for what follows. The widow delivers a series of bites as the creature’s struggles diminish, injecting digestive fluids. Finally she will settle down to suck the liquefied innards out of the prey, changing position two or three times to get it all.

Before the eating begins, and sometimes before the slow venom quiets the victim, the widow usually moves the meal higher into the web. She attaches some line to the prey with a leg-bicycling toss, moves up the vertical web-strand which originally snagged the prey, crosses a diagonal strand upward into the cross-hatched main body of the web, and here secures the line. Then she hauls on the attached line to raise the prey so that its struggles cause it to touch other strands. She has effectively moved a load with block and tackle. The operation occurs in three dimensions -- as opposed to the essentially two-dimensional operations of the familiar orb-weavers.

You can't watch the widow in this activity very long without realizing that its web is not a mess at all, but an efficient machine. It allows complicated uses of leverage, and also, because of its complexity of connections, lets the spider feel a disturbance anywhere in the web--usually with enough accuracy to tell the difference at a distance between a raindrop or leaf and viable prey. The web is also constructed in a certain relationship to movements of air, so that flying insects are drawn into it. This fact partly explains why widow webs are so often found in the face-down side of discarded car wheels--the wheel is essentially a vault of still air that protects the web, but the central hole at the top allows airborne insects to fall in. A clumsy flying insect, such as a June beetle, is especially vulnerable to this trap.

Widows adapt their webs to the opportunities of their neighborhoods. Some choose building sites according to indigenous smells. Webs turn up, for example, in piles of trash and rotting wood, the web holding together a camouflage of leaves, dirt, or bark. A few decades ago, the widow was notorious for building its home in another odorous habitat--outdoor toilets. Some people would habitually take a stick to the outhouse with them. Before conducting the business for which they had come, they would scrape under the seat and inside the hole with the stick, listening carefully for a sound like the crackling of paper in fire. This sound is unique to the widow's powerful web. Anybody with a little experience can tell a widow's work from another spider's by ear.

Widows move around in their webs almost blind, yet they never misstep or get lost. In fact, a widow knocked loose from its web does not seem confused; it will quickly climb back to its habitual resting place. Furthermore, widows never snare themselves, even though every strand of the web, except for the scaffolding, is a potential trap. A widow will spend a few minutes every day coating the clawed tips of its legs with the oil that lets it walk the sticky strands. It secretes the oil from its mouth, licking its legs like a cat cleaning its paws.

The human mind cannot grasp the complex functions of the web, but must infer them. The widow constructs it by instinct. A ganglion smaller than a pinhead -- it’s too primitive to be called a brain -- contains the blueprints, precognitive memories the widow unfolds out of itself into actuality. I have never dissected with enough precision or delicacy to get a good specimen of the black widow’s tiny ganglion, but I did glimpse one once. A widow was struggling to wrap a mantid when the insect's forelegs, like scalpels mounted on lightning, sliced away the spider's carapace and left exposed among the ooze of torn venom sacs a clear droplet of bloody primitive brain.

*

Widows have been known to snare and eat mice, frogs, snails, tarantulas, lizards, snakes -- almost anything that wanders into that remarkable web. I have never witnessed a widow performing a gustatory act of that magnitude, but I have seen them eat scarab beetles heavy as pecans, cockroaches more than an inch long, bumblebees, Mormon crickets, and hundreds of other arthropods of various sizes. I have seen widows eat butterflies and ants that most spiders reject on the grounds of bad flavor. I have seen them conquer spider-eating insects such as adult mantids and mud-dauber wasps. The combination of web and venom enables widows to overcome predators whose size and strength would otherwise overwhelm them.

Many widows will eat as much as opportunity gives. One aggressive female had an abdomen a little bigger than an English pea. She snared a huge cockroach and spent several hours subduing it, then three days consuming it. Her abdomen swelled to the size of a largish marble, its glossy black stretching to a tight red-brown. With a different widow, I decided to see whether that appetite was really insatiable. I collected dozens of large crickets and grasshoppers and began to drop them into her web at a rate of one every three or four hours. After catching and consuming her tenth victim, this bloated widow fell from her web, landing on her back. She remained in this position for hours, making only feeble attempts to move. Then she died.

The widow gets her name by eating her mate, though this does not always happen. When a male matures with his last molt, he abandons his sedentary web-sitting ways. He spins a little patch of silk and squeezes a drop of sperm-rich fluid onto it. Then he sucks the fluid into the knobs at the end of his pedipalps and goes wandering in search females. When he finds a web, he recognizes it as that of a female of the appropriate species by scent -- the female’s silk is laden with pheromones. Before approaching the female, the male tinkers mysteriously at the edge of her web for a while, cutting a few strands, balling up the cut silk, and otherwise altering attachments. Apparently he is sabotaging the web so the vibratory messages the female receives will be imprecise. He thus creates a blind spot in her view of the world. This tactic makes it harder for her to find and kill him. Then he’s ready to approach her. He distinguishes himself from ordinary prey by playing her web like a lyre, stroking it with his front legs and vibrating his belly against the strands. Sometimes the female eats the male without first copulating; sometimes she snags him as he withdraws his palp from her genital pore; sometimes he leaves unharmed after mating. I have even witnessed male and female living in apparently platonic relationships in one web.

Mating is the last thing a male does. Once he’s left his web to seek mates, he never eats again; and whether he finds females or not, he is already wasting away, collapsing toward his preordained life-limit, which is marked by the coming of the cold.

*

The first thing people ask when they hear about my fascination with the widow is why I am not afraid. The truth is that my fascination is rooted in fear.

I have childhood memories that partly account for my fear. When I was six my mother took my sister and me to the cellar of our farmhouse and told us to watch as she killed a widow. With great ceremony she produced a long stick (I am tempted to say a ten-foot pole) and, narrating her technique in exactly the hushed voice she used for discussing religion or sex, went to work. Her flashlight beam found a point halfway up the cement wall where two marbles hung together -- one crisp white, the other a glossy black. My mother ran her stick through the dirty silver web around them, and as it tore she made us listen to the crackle. The black marble rose on thin legs to fight off the intruder. As the plump abdomen wobbled across the wall, it seemed to be constantly throwing those legs out of its path. It gave the impression of speed and frantic anger, but actually a widow's movements outside the web are slow and inefficient. My mother smashed the widow onto the stick and carried it up into the light. It was still kicking its remaining legs. She scraped it against the sidewalk, grinding it to a paste. Then she returned for the white marble -- the widow's egg sac. This, too, came to an abrasive end.

My mother's purpose was to teach us how to recognize and deal with a dangerous creature we would probably encounter on the farm. But of course we also took the understanding that widows were actively malevolent, that they waited in dark places to ambush us, that they were worthy of ritual disposition, like an enemy whose death is not sufficient but must be followed with the murder of his children and the salting of his land and whose unclean remains must not touch our hands.

The odd thing is that so many people, some of whom presumably did not first encounter the widow in such an atmosphere of mystic reverence, hold her in awe. Various friends have told me that the widow always devours her mate, or that her bite is always fatal to humans--in fact, it rarely is, especially since the development of an antivenin. I have heard told for truth that goods imported from Asia are likely infested with widows and that women with Bouffant hairdos have died of widow infestation. Any contradiction of such tales is received as if it were a proclamation of atheism.

Scientific researchers are not immune to the widow’s mythic aura. The most startling contribution to the widow's mythical status I’ve ever encountered was Black Widow: America's Most Poisonous Spider, a book by Thorpe and Woodson that appeared in 1945. This book enjoyed respect in scientific circles. It was cited in scientific literature for decades after it appeared; its survey of medical cases and laboratory experiments was thorough. However, between their responsible scientific observations, the authors present the widow as a lurking menace with a taste for human flesh. “Mankind must now make a unified effort toward curtailment of the greatest arachnid menace the world has ever known,” they proclaim. The widow population is exploding, they announce with scant evidence, making it a danger of enormous urgency. They describe certain experiments conducted in the name of making the world safe from widows; one involved inducing a widow to bite a laboratory rat on the penis, after which event the rat “appeared to become dejected and depressed.” Perhaps the most psychologically revealing passage is the authors' quotation from another writer, who said the "deadliest Communists are like the black widow spider; they conceal their redunderneath."

We project our archetypal terrors onto the widow. It is black; it avoids the light; it is a voracious carnivore. Its red markings suggest blood. Its name, its sleek, rounded form, invite a strangely sexual discomfort; the widow becomes an emblem for a man's fear of extending himself into the blood and darkness of a woman, something like the vampire of Inuit legend that takes the form of a fanged vagina.

*

The widow's venom is, of course, a soundly pragmatic reason for fear. It contains a neurotoxin that can produce sweats, vomiting, swelling, convulsions, and dozens of other symptoms. The variation in symptoms from one person to the next is remarkable. The constant is pain. A useful question for a doctor trying to diagnose an uncertain case: “Is this the worst pain you’ve ever felt?” A “yes” suggests a diagnosis of black widow bite. Occasionally people die from widow bites. The very young and the very old are especially vulnerable. Some people die not from the venom but from the complications that may follow a bite--stroke, tetanus, gangrene.

Some early researchers hypothesized that the virulence of the venom was necessary for killing scarab beetles. The scarab family contains thousands of species, including the June beetle and the famous dung beetle the Egyptians thought immortal. All the scarabs have thick, strong bodies and tough exoskeletons, and many of them are common prey for the widow. The tough hide was supposed to require a particularly nasty venom. As it turns out, the widow’s venom is thousands of times more virulent than necessary for killing scarabs. The whole idea is full of the widow's glamor: an emblem of eternal life killed by a creature whose most distinctive blood-colored markings people invariably describe as an hourglass.

No one has ever offered a sufficient explanation for the dangerous venom. It provides no clear evolutionary advantage: all of the widow's prey items would find lesser toxins fatal, and there is no particular benefit in killing or harming larger animals. A widow that bites a human being or other large animal is likely to be killed. Evolution does sometimes produce such flowers of natural evil -- traits that are neither functional nor vestigial, but utterly pointless. Natural selection favors the inheritance of useful characteristics that arise from random mutation and tends to extinguish disadvantageous traits. All other characteristics, the ones that neither help nor hinder survival, are preserved or extinguished at random as mutation links them with useful or harmful traits. Many people--even many scientists --assume that every animal is elegantly engineered for its ecological niche, that every bit of an animal's anatomy and behavior has a functional explanation. However, nothing in evolutionary theory sanctions this assumption. Close observation of the lives around us rules out any view so systematic.

We want the world to be an ordered room, but in a corner of that room there hangs an untidy web. Here the analytical mind finds an irreducible mystery, a motiveless evil in nature; and the scientist's vision of evil comes to match the vision of a God-fearing country woman with a ten-foot pole. No idea of the cosmos as elegant design accounts for the widow. No idea of a benevolent God is comfortable in a world with the widow. She hangs in her web, that marvel of design, and defies teleology.

This essay appears, in a much-expanded form, in my collection The Red Hourglass.

Angela Rotherman/Creative Commons

Angela Rotherman/Creative CommonsI hunt black widow spiders. When I find one, I capture it. I have found them in discarded car wheels and under railroad ties. I have found them in house foundations and cellars, in automotive shops and tool sheds, against fences and in cinder block walls. As a boy I used to lift the iron lids that guarded underground water meters, and there in the darkness of the meter-wells I would often see something round as a flensed human skull, glinting like chipped obsidian, scarred with a pair of crimson triangles that touched each other to form an hourglass: the widow as she looks in shadow. A quick stir with a stick would trap her for a few seconds in her own web, long enough for me to catch her in a jar. I have found widows on playground equipment, in a hospital, in the lair of a rattlesnake, and once on the bottom of the lawn chair I was sitting in as I looked at some widows I had captured elsewhere that day.

Sometimes I raise a generation or two in captivity. An egg sac hatches hundreds of pinpoint cannibals, each leaving a trail of gleaming light in the air, the group of them eventually producing a glimmering tangle in which most of them die, eaten by stronger sibs. Finally I separate the three or four survivors and feed them bigger game.

Once I let eleven egg sacs hatch out in a container about eighteen inches on a side, a tight wooden box with a sliding glass top. As I tried to move the box one day, I tripped. The lid slid off and I fell, hands first, into the mass of young widows. Most were still translucent newborns, their bodies a swirl of cream and brown . A few of the females were past their second molt; they had the beginnings of their blackness. Tangles of broken web clung to my forearms. The spiderlings felt like trickling water among my arm hairs.

I walked out into the open air and raised my arms into the stiff wind. The widows answered the wind with new strands of web and drifted away, their bodies gold in the afternoon sun. In about ten minutes my arms carried nothing but old web and the husks of spiderlings eaten by their sibs.

I have never been bitten.

*

The black widow has an ugly web. The orb weavers make those seemingly delicate nets that poets have traditionally used as symbols of imagination, order, and perfection. The sheet-web spiders weave crisp linens on grass and bushes. But the widow makes messy-looking tangles in the corners and bends of things and under logs and debris. Often the web is littered with leaves. Beneath it lie the husks of insect prey, their antennae stiff as gargoyle horns, cut loose and dropped; on them and the surrounding ground are splashes of the spider's white urine, which looks like bird guano and smells of ammonia even at a distance of several feet. This fetid material draws scavengers -- ants, crickets, roaches, and so on -- which become tangled in vertical strands of silk reaching from the ground to the main body of the web. Sometimes these vertical strands break and recoil, hoisting the new prey as if on a bungee cord. The widow comes down and, with a bicycling of the hind pair of legs, throws gummy silk onto the victim.

When the prey is seriously tangled but still struggling, the widow cautiously descends and bites the creature, usually on a leg joint. This bite pumps neurotoxin into the victim, paralyzing it; it remains alive but immobile for what follows. The widow delivers a series of bites as the creature’s struggles diminish, injecting digestive fluids. Finally she will settle down to suck the liquefied innards out of the prey, changing position two or three times to get it all.

Before the eating begins, and sometimes before the slow venom quiets the victim, the widow usually moves the meal higher into the web. She attaches some line to the prey with a leg-bicycling toss, moves up the vertical web-strand which originally snagged the prey, crosses a diagonal strand upward into the cross-hatched main body of the web, and here secures the line. Then she hauls on the attached line to raise the prey so that its struggles cause it to touch other strands. She has effectively moved a load with block and tackle. The operation occurs in three dimensions -- as opposed to the essentially two-dimensional operations of the familiar orb-weavers.

You can't watch the widow in this activity very long without realizing that its web is not a mess at all, but an efficient machine. It allows complicated uses of leverage, and also, because of its complexity of connections, lets the spider feel a disturbance anywhere in the web--usually with enough accuracy to tell the difference at a distance between a raindrop or leaf and viable prey. The web is also constructed in a certain relationship to movements of air, so that flying insects are drawn into it. This fact partly explains why widow webs are so often found in the face-down side of discarded car wheels--the wheel is essentially a vault of still air that protects the web, but the central hole at the top allows airborne insects to fall in. A clumsy flying insect, such as a June beetle, is especially vulnerable to this trap.

Widows adapt their webs to the opportunities of their neighborhoods. Some choose building sites according to indigenous smells. Webs turn up, for example, in piles of trash and rotting wood, the web holding together a camouflage of leaves, dirt, or bark. A few decades ago, the widow was notorious for building its home in another odorous habitat--outdoor toilets. Some people would habitually take a stick to the outhouse with them. Before conducting the business for which they had come, they would scrape under the seat and inside the hole with the stick, listening carefully for a sound like the crackling of paper in fire. This sound is unique to the widow's powerful web. Anybody with a little experience can tell a widow's work from another spider's by ear.

Widows move around in their webs almost blind, yet they never misstep or get lost. In fact, a widow knocked loose from its web does not seem confused; it will quickly climb back to its habitual resting place. Furthermore, widows never snare themselves, even though every strand of the web, except for the scaffolding, is a potential trap. A widow will spend a few minutes every day coating the clawed tips of its legs with the oil that lets it walk the sticky strands. It secretes the oil from its mouth, licking its legs like a cat cleaning its paws.

The human mind cannot grasp the complex functions of the web, but must infer them. The widow constructs it by instinct. A ganglion smaller than a pinhead -- it’s too primitive to be called a brain -- contains the blueprints, precognitive memories the widow unfolds out of itself into actuality. I have never dissected with enough precision or delicacy to get a good specimen of the black widow’s tiny ganglion, but I did glimpse one once. A widow was struggling to wrap a mantid when the insect's forelegs, like scalpels mounted on lightning, sliced away the spider's carapace and left exposed among the ooze of torn venom sacs a clear droplet of bloody primitive brain.

*

Widows have been known to snare and eat mice, frogs, snails, tarantulas, lizards, snakes -- almost anything that wanders into that remarkable web. I have never witnessed a widow performing a gustatory act of that magnitude, but I have seen them eat scarab beetles heavy as pecans, cockroaches more than an inch long, bumblebees, Mormon crickets, and hundreds of other arthropods of various sizes. I have seen widows eat butterflies and ants that most spiders reject on the grounds of bad flavor. I have seen them conquer spider-eating insects such as adult mantids and mud-dauber wasps. The combination of web and venom enables widows to overcome predators whose size and strength would otherwise overwhelm them.

Many widows will eat as much as opportunity gives. One aggressive female had an abdomen a little bigger than an English pea. She snared a huge cockroach and spent several hours subduing it, then three days consuming it. Her abdomen swelled to the size of a largish marble, its glossy black stretching to a tight red-brown. With a different widow, I decided to see whether that appetite was really insatiable. I collected dozens of large crickets and grasshoppers and began to drop them into her web at a rate of one every three or four hours. After catching and consuming her tenth victim, this bloated widow fell from her web, landing on her back. She remained in this position for hours, making only feeble attempts to move. Then she died.

The widow gets her name by eating her mate, though this does not always happen. When a male matures with his last molt, he abandons his sedentary web-sitting ways. He spins a little patch of silk and squeezes a drop of sperm-rich fluid onto it. Then he sucks the fluid into the knobs at the end of his pedipalps and goes wandering in search females. When he finds a web, he recognizes it as that of a female of the appropriate species by scent -- the female’s silk is laden with pheromones. Before approaching the female, the male tinkers mysteriously at the edge of her web for a while, cutting a few strands, balling up the cut silk, and otherwise altering attachments. Apparently he is sabotaging the web so the vibratory messages the female receives will be imprecise. He thus creates a blind spot in her view of the world. This tactic makes it harder for her to find and kill him. Then he’s ready to approach her. He distinguishes himself from ordinary prey by playing her web like a lyre, stroking it with his front legs and vibrating his belly against the strands. Sometimes the female eats the male without first copulating; sometimes she snags him as he withdraws his palp from her genital pore; sometimes he leaves unharmed after mating. I have even witnessed male and female living in apparently platonic relationships in one web.

Mating is the last thing a male does. Once he’s left his web to seek mates, he never eats again; and whether he finds females or not, he is already wasting away, collapsing toward his preordained life-limit, which is marked by the coming of the cold.

*

The first thing people ask when they hear about my fascination with the widow is why I am not afraid. The truth is that my fascination is rooted in fear.

I have childhood memories that partly account for my fear. When I was six my mother took my sister and me to the cellar of our farmhouse and told us to watch as she killed a widow. With great ceremony she produced a long stick (I am tempted to say a ten-foot pole) and, narrating her technique in exactly the hushed voice she used for discussing religion or sex, went to work. Her flashlight beam found a point halfway up the cement wall where two marbles hung together -- one crisp white, the other a glossy black. My mother ran her stick through the dirty silver web around them, and as it tore she made us listen to the crackle. The black marble rose on thin legs to fight off the intruder. As the plump abdomen wobbled across the wall, it seemed to be constantly throwing those legs out of its path. It gave the impression of speed and frantic anger, but actually a widow's movements outside the web are slow and inefficient. My mother smashed the widow onto the stick and carried it up into the light. It was still kicking its remaining legs. She scraped it against the sidewalk, grinding it to a paste. Then she returned for the white marble -- the widow's egg sac. This, too, came to an abrasive end.

My mother's purpose was to teach us how to recognize and deal with a dangerous creature we would probably encounter on the farm. But of course we also took the understanding that widows were actively malevolent, that they waited in dark places to ambush us, that they were worthy of ritual disposition, like an enemy whose death is not sufficient but must be followed with the murder of his children and the salting of his land and whose unclean remains must not touch our hands.

The odd thing is that so many people, some of whom presumably did not first encounter the widow in such an atmosphere of mystic reverence, hold her in awe. Various friends have told me that the widow always devours her mate, or that her bite is always fatal to humans--in fact, it rarely is, especially since the development of an antivenin. I have heard told for truth that goods imported from Asia are likely infested with widows and that women with Bouffant hairdos have died of widow infestation. Any contradiction of such tales is received as if it were a proclamation of atheism.

Scientific researchers are not immune to the widow’s mythic aura. The most startling contribution to the widow's mythical status I’ve ever encountered was Black Widow: America's Most Poisonous Spider, a book by Thorpe and Woodson that appeared in 1945. This book enjoyed respect in scientific circles. It was cited in scientific literature for decades after it appeared; its survey of medical cases and laboratory experiments was thorough. However, between their responsible scientific observations, the authors present the widow as a lurking menace with a taste for human flesh. “Mankind must now make a unified effort toward curtailment of the greatest arachnid menace the world has ever known,” they proclaim. The widow population is exploding, they announce with scant evidence, making it a danger of enormous urgency. They describe certain experiments conducted in the name of making the world safe from widows; one involved inducing a widow to bite a laboratory rat on the penis, after which event the rat “appeared to become dejected and depressed.” Perhaps the most psychologically revealing passage is the authors' quotation from another writer, who said the "deadliest Communists are like the black widow spider; they conceal their redunderneath."

We project our archetypal terrors onto the widow. It is black; it avoids the light; it is a voracious carnivore. Its red markings suggest blood. Its name, its sleek, rounded form, invite a strangely sexual discomfort; the widow becomes an emblem for a man's fear of extending himself into the blood and darkness of a woman, something like the vampire of Inuit legend that takes the form of a fanged vagina.

*

The widow's venom is, of course, a soundly pragmatic reason for fear. It contains a neurotoxin that can produce sweats, vomiting, swelling, convulsions, and dozens of other symptoms. The variation in symptoms from one person to the next is remarkable. The constant is pain. A useful question for a doctor trying to diagnose an uncertain case: “Is this the worst pain you’ve ever felt?” A “yes” suggests a diagnosis of black widow bite. Occasionally people die from widow bites. The very young and the very old are especially vulnerable. Some people die not from the venom but from the complications that may follow a bite--stroke, tetanus, gangrene.

Some early researchers hypothesized that the virulence of the venom was necessary for killing scarab beetles. The scarab family contains thousands of species, including the June beetle and the famous dung beetle the Egyptians thought immortal. All the scarabs have thick, strong bodies and tough exoskeletons, and many of them are common prey for the widow. The tough hide was supposed to require a particularly nasty venom. As it turns out, the widow’s venom is thousands of times more virulent than necessary for killing scarabs. The whole idea is full of the widow's glamor: an emblem of eternal life killed by a creature whose most distinctive blood-colored markings people invariably describe as an hourglass.

No one has ever offered a sufficient explanation for the dangerous venom. It provides no clear evolutionary advantage: all of the widow's prey items would find lesser toxins fatal, and there is no particular benefit in killing or harming larger animals. A widow that bites a human being or other large animal is likely to be killed. Evolution does sometimes produce such flowers of natural evil -- traits that are neither functional nor vestigial, but utterly pointless. Natural selection favors the inheritance of useful characteristics that arise from random mutation and tends to extinguish disadvantageous traits. All other characteristics, the ones that neither help nor hinder survival, are preserved or extinguished at random as mutation links them with useful or harmful traits. Many people--even many scientists --assume that every animal is elegantly engineered for its ecological niche, that every bit of an animal's anatomy and behavior has a functional explanation. However, nothing in evolutionary theory sanctions this assumption. Close observation of the lives around us rules out any view so systematic.

We want the world to be an ordered room, but in a corner of that room there hangs an untidy web. Here the analytical mind finds an irreducible mystery, a motiveless evil in nature; and the scientist's vision of evil comes to match the vision of a God-fearing country woman with a ten-foot pole. No idea of the cosmos as elegant design accounts for the widow. No idea of a benevolent God is comfortable in a world with the widow. She hangs in her web, that marvel of design, and defies teleology.

This essay appears, in a much-expanded form, in my collection The Red Hourglass.

Published on May 02, 2015 09:00

April 25, 2015

Paintings by Heade

Martin Johnson Heade, 1819-1904.

Orchid and Spray-Orchid with Hummingbird

Orchid and Spray-Orchid with Hummingbird

Orchid and Hummingbird

Orchid and Hummingbird

Blue Morpho Butterfly

Blue Morpho Butterfly

Orchid and Hummingbird near a Mountain Waterfall

Orchid and Hummingbird near a Mountain Waterfall

Sunrise in Nicaragua

Sunrise in Nicaragua

Orchid and Spray-Orchid with Hummingbird

Orchid and Spray-Orchid with Hummingbird Orchid and Hummingbird

Orchid and Hummingbird Blue Morpho Butterfly

Blue Morpho Butterfly Orchid and Hummingbird near a Mountain Waterfall

Orchid and Hummingbird near a Mountain Waterfall Sunrise in Nicaragua

Sunrise in Nicaragua

Published on April 25, 2015 09:00

April 18, 2015

Scary Story: Edgar Allan Poe's Ragged Mountains

Pfctdayelise/Creative Commons

Pfctdayelise/Creative CommonsA TALE OF THE RAGGED MOUNTAINS

Edgar Allan Poe

DURING the fall of the year 1827, while residing near Charlottesville, Virginia, I casually made the acquaintance of Mr. Augustus Bedloe. This young gentleman was remarkable in every respect, and excited in me a profound interest and curiosity. I found it impossible to comprehend him either in his moral or his physical relations. Of his family I could obtain no satisfactory account. Whence he came, I never ascertained. Even about his age—although I call him a young gentleman—there was something which perplexed me in no little degree. He certainly seemed young—and he made a point of speaking about his youth—yet there were moments when I should have had little trouble in imagining him a hundred years of age. But in no regard was he more peculiar than in his personal appearance. He was singularly tall and thin. He stooped much. His limbs were exceedingly long and emaciated. His forehead was broad and low. His complexion was absolutely bloodless. His mouth was large and flexible, and his teeth were more wildly uneven, although sound, than I had ever before seen teeth in a human head. The expression of his smile, however, was by no means unpleasing, as might be supposed; but it had no variation whatever. It was one of profound melancholy—of a phaseless and unceasing gloom. His eyes were abnormally large, and round like those of a cat. The pupils, too, upon any accession or diminution of light, underwent contraction or dilation, just such as is observed in the feline tribe. In moments of excitement the orbs grew bright to a degree almost inconceivable; seeming to emit luminous rays, not of a reflected but of an intrinsic lustre, as does a candle or the sun; yet their ordinary condition was so totally vapid, filmy, and dull as to convey the idea of the eyes of a long-interred corpse.

These peculiarities of person appeared to cause him much annoyance, and he was continually alluding to them in a sort of half explanatory, half apologetic strain, which, when I first heard it, impressed me very painfully. I soon, however, grew accustomed to it, and my uneasiness wore off. It seemed to be his design rather to insinuate than directly to assert that, physically, he had not always been what he was—that a long series of neuralgic attacks had reduced him from a condition of more than usual personal beauty, to that which I saw. For many years past he had been attended by a physician, named Templeton—an old gentleman, perhaps seventy years of age—whom he had first encountered at Saratoga, and from whose attention, while there, he either received, or fancied that he received, great benefit. The result was that Bedloe, who was wealthy, had made an arrangement with Dr. Templeton, by which the latter, in consideration of a liberal annual allowance, had consented to devote his time and medical experience exclusively to the care of the invalid.

Doctor Templeton had been a traveller in his younger days, and at Paris had become a convert, in great measure, to the doctrines of Mesmer. It was altogether by means of magnetic remedies that he had succeeded in alleviating the acute pains of his patient; and this success had very naturally inspired the latter with a certain degree of confidence in the opinions from which the remedies had been educed. The Doctor, however, like all enthusiasts, had struggled hard to make a thorough convert of his pupil, and finally so far gained his point as to induce the sufferer to submit to numerous experiments. By a frequent repetition of these, a result had arisen, which of late days has become so common as to attract little or no attention, but which, at the period of which I write, had very rarely been known in America. I mean to say, that between Doctor Templeton and Bedloe there had grown up, little by little, a very distinct and strongly marked rapport, or magnetic relation. I am not prepared to assert, however, that this rapport extended beyond the limits of the simple sleep-producing power, but this power itself had attained great intensity. At the first attempt to induce the magnetic somnolency, the mesmerist entirely failed. In the fifth or sixth he succeeded very partially, and after long continued effort. Only at the twelfth was the triumph complete. After this the will of the patient succumbed rapidly to that of the physician, so that, when I first became acquainted with the two, sleep was brought about almost instantaneously by the mere volition of the operator, even when the invalid was unaware of his presence. It is only now, in the year 1845, when similar miracles are witnessed daily by thousands, that I dare venture to record this apparent impossibility as a matter of serious fact.

The temperature of Bedloe was, in the highest degree sensitive, excitable, enthusiastic. His imagination was singularly vigorous and creative; and no doubt it derived additional force from the habitual use of morphine, which he swallowed in great quantity, and without which he would have found it impossible to exist. It was his practice to take a very large dose of it immediately after breakfast each morning—or, rather, immediately after a cup of strong coffee, for he ate nothing in the forenoon—and then set forth alone, or attended only by a dog, upon a long ramble among the chain of wild and dreary hills that lie westward and southward of Charlottesville, and are there dignified by the title of the Ragged Mountains.

Upon a dim, warm, misty day, toward the close of November, and during the strange interregnum of the seasons which in America is termed the Indian Summer, Mr. Bedloe departed as usual for the hills. The day passed, and still he did not return.

About eight o'clock at night, having become seriously alarmed at his protracted absence, we were about setting out in search of him, when he unexpectedly made his appearance, in health no worse than usual, and in rather more than ordinary spirits. The account which he gave of his expedition, and of the events which had detained him, was a singular one indeed.

"You will remember," said he, "that it was about nine in the morning when I left Charlottesville. I bent my steps immediately to the mountains, and, about ten, entered a gorge which was entirely new to me. I followed the windings of this pass with much interest. The scenery which presented itself on all sides, although scarcely entitled to be called grand, had about it an indescribable and to me a delicious aspect of dreary desolation. The solitude seemed absolutely virgin. I could not help believing that the green sods and the gray rocks upon which I trod had been trodden never before by the foot of a human being. So entirely secluded, and in fact inaccessible, except through a series of accidents, is the entrance of the ravine, that it is by no means impossible that I was indeed the first adventurer—the very first and sole adventurer who had ever penetrated its recesses.

"The thick and peculiar mist, or smoke, which distinguishes the Indian Summer, and which now hung heavily over all objects, served, no doubt, to deepen the vague impressions which these objects created. So dense was this pleasant fog that I could at no time see more than a dozen yards of the path before me. This path was excessively sinuous, and as the sun could not be seen, I soon lost all idea of the direction in which I journeyed. In the meantime the morphine had its customary effect—that of enduing all the external world with an intensity of interest. In the quivering of a leaf—in the hue of a blade of grass—in the shape of a trefoil—in the humming of a bee—in the gleaming of a dew-drop—in the breathing of the wind—in the faint odors that came from the forest—there came a whole universe of suggestion—a gay and motley train of rhapsodical and immethodical thought.

"Busied in this, I walked on for several hours, during which the mist deepened around me to so great an extent that at length I was reduced to an absolute groping of the way. And now an indescribable uneasiness possessed me—a species of nervous hesitation and tremor. I feared to tread, lest I should be precipitated into some abyss. I remembered, too, strange stories told about these Ragged Hills, and of the uncouth and fierce races of men who tenanted their groves and caverns. A thousand vague fancies oppressed and disconcerted me—fancies the more distressing because vague. Very suddenly my attention was arrested by the loud beating of a drum.

"My amazement was, of course, extreme. A drum in these hills was a thing unknown. I could not have been more surprised at the sound of the trump of the Archangel. But a new and still more astounding source of interest and perplexity arose. There came a wild rattling or jingling sound, as if of a bunch of large keys, and upon the instant a dusky-visaged and half-naked man rushed past me with a shriek. He came so close to my person that I felt his hot breath upon my face. He bore in one hand an instrument composed of an assemblage of steel rings, and shook them vigorously as he ran. Scarcely had he disappeared in the mist before, panting after him, with open mouth and glaring eyes, there darted a huge beast. I could not be mistaken in its character. It was a hyena.

"The sight of this monster rather relieved than heightened my terrors—for I now made sure that I dreamed, and endeavored to arouse myself to waking consciousness. I stepped boldly and briskly forward. I rubbed my eyes. I called aloud. I pinched my limbs. A small spring of water presented itself to my view, and here, stooping, I bathed my hands and my head and neck. This seemed to dissipate the equivocal sensations which had hitherto annoyed me. I arose, as I thought, a new man, and proceeded steadily and complacently on my unknown way.

"At length, quite overcome by exertion, and by a certain oppressive closeness of the atmosphere, I seated myself beneath a tree. Presently there came a feeble gleam of sunshine, and the shadow of the leaves of the tree fell faintly but definitely upon the grass. At this shadow I gazed wonderingly for many minutes. Its character stupefied me with astonishment. I looked upward. The tree was a palm.

"I now arose hurriedly, and in a state of fearful agitation—for the fancy that I dreamed would serve me no longer. I saw—I felt that I had perfect command of my senses—and these senses now brought to my soul a world of novel and singular sensation. The heat became all at once intolerable. A strange odor loaded the breeze. A low, continuous murmur, like that arising from a full, but gently flowing river, came to my ears, intermingled with the peculiar hum of multitudinous human voices.

"While I listened in an extremity of astonishment which I need not attempt to describe, a strong and brief gust of wind bore off the incumbent fog as if by the wand of an enchanter.

"I found myself at the foot of a high mountain, and looking down into a vast plain, through which wound a majestic river. On the margin of this river stood an Eastern-looking city, such as we read of in the Arabian Tales, but of a character even more singular than any there described. From my position, which was far above the level of the town, I could perceive its every nook and corner, as if delineated on a map. The streets seemed innumerable, and crossed each other irregularly in all directions, but were rather long winding alleys than streets, and absolutely swarmed with inhabitants. The houses were wildly picturesque. On every hand was a wilderness of balconies, of verandas, of minarets, of shrines, and fantastically carved oriels. Bazaars abounded; and in these were displayed rich wares in infinite variety and profusion—silks, muslins, the most dazzling cutlery, the most magnificent jewels and gems. Besides these things, were seen, on all sides, banners and palanquins, litters with stately dames close veiled, elephants gorgeously caparisoned, idols grotesquely hewn, drums, banners, and gongs, spears, silver and gilded maces. And amid the crowd, and the clamor, and the general intricacy and confusion—amid the million of black and yellow men, turbaned and robed, and of flowing beard, there roamed a countless multitude of holy filleted bulls, while vast legions of the filthy but sacred ape clambered, chattering and shrieking, about the cornices of the mosques, or clung to the minarets and oriels. From the swarming streets to the banks of the river, there descended innumerable flights of steps leading to bathing places, while the river itself seemed to force a passage with difficulty through the vast fleets of deeply—burthened ships that far and wide encountered its surface. Beyond the limits of the city arose, in frequent majestic groups, the palm and the cocoa, with other gigantic and weird trees of vast age, and here and there might be seen a field of rice, the thatched hut of a peasant, a tank, a stray temple, a gypsy camp, or a solitary graceful maiden taking her way, with a pitcher upon her head, to the banks of the magnificent river.

"You will say now, of course, that I dreamed; but not so. What I saw—what I heard—what I felt—what I thought—had about it nothing of the unmistakable idiosyncrasy of the dream. All was rigorously self-consistent. At first, doubting that I was really awake, I entered into a series of tests, which soon convinced me that I really was. Now, when one dreams, and, in the dream, suspects that he dreams, the suspicion never fails to confirm itself, and the sleeper is almost immediately aroused. Thus Novalis errs not in saying that 'we are near waking when we dream that we dream.' Had the vision occurred to me as I describe it, without my suspecting it as a dream, then a dream it might absolutely have been, but, occurring as it did, and suspected and tested as it was, I am forced to class it among other phenomena."

"In this I am not sure that you are wrong," observed Dr. Templeton, "but proceed. You arose and descended into the city."

"I arose," continued Bedloe, regarding the Doctor with an air of profound astonishment "I arose, as you say, and descended into the city. On my way I fell in with an immense populace, crowding through every avenue, all in the same direction, and exhibiting in every action the wildest excitement. Very suddenly, and by some inconceivable impulse, I became intensely imbued with personal interest in what was going on. I seemed to feel that I had an important part to play, without exactly understanding what it was. Against the crowd which environed me, however, I experienced a deep sentiment of animosity. I shrank from amid them, and, swiftly, by a circuitous path, reached and entered the city. Here all was the wildest tumult and contention. A small party of men, clad in garments half-Indian, half-European, and officered by gentlemen in a uniform partly British, were engaged, at great odds, with the swarming rabble of the alleys. I joined the weaker party, arming myself with the weapons of a fallen officer, and fighting I knew not whom with the nervous ferocity of despair. We were soon overpowered by numbers, and driven to seek refuge in a species of kiosk. Here we barricaded ourselves, and, for the present were secure. From a loop-hole near the summit of the kiosk, I perceived a vast crowd, in furious agitation, surrounding and assaulting a gay palace that overhung the river. Presently, from an upper window of this place, there descended an effeminate-looking person, by means of a string made of the turbans of his attendants. A boat was at hand, in which he escaped to the opposite bank of the river.

"And now a new object took possession of my soul. I spoke a few hurried but energetic words to my companions, and, having succeeded in gaining over a few of them to my purpose made a frantic sally from the kiosk. We rushed amid the crowd that surrounded it. They retreated, at first, before us. They rallied, fought madly, and retreated again. In the mean time we were borne far from the kiosk, and became bewildered and entangled among the narrow streets of tall, overhanging houses, into the recesses of which the sun had never been able to shine. The rabble pressed impetuously upon us, harrassing us with their spears, and overwhelming us with flights of arrows. These latter were very remarkable, and resembled in some respects the writhing creese of the Malay. They were made to imitate the body of a creeping serpent, and were long and black, with a poisoned barb. One of them struck me upon the right temple. I reeled and fell. An instantaneous and dreadful sickness seized me. I struggled—I gasped—I died." "You will hardly persist now," said I smiling, "that the whole of your adventure was not a dream. You are not prepared to maintain that you are dead?"

When I said these words, I of course expected some lively sally from Bedloe in reply, but, to my astonishment, he hesitated, trembled, became fearfully pallid, and remained silent. I looked toward Templeton. He sat erect and rigid in his chair—his teeth chattered, and his eyes were starting from their sockets. "Proceed!" he at length said hoarsely to Bedloe.

"For many minutes," continued the latter, "my sole sentiment—my sole feeling—was that of darkness and nonentity, with the consciousness of death. At length there seemed to pass a violent and sudden shock through my soul, as if of electricity. With it came the sense of elasticity and of light. This latter I felt—not saw. In an instant I seemed to rise from the ground. But I had no bodily, no visible, audible, or palpable presence. The crowd had departed. The tumult had ceased. The city was in comparative repose. Beneath me lay my corpse, with the arrow in my temple, the whole head greatly swollen and disfigured. But all these things I felt—not saw. I took interest in nothing. Even the corpse seemed a matter in which I had no concern. Volition I had none, but appeared to be impelled into motion, and flitted buoyantly out of the city, retracing the circuitous path by which I had entered it. When I had attained that point of the ravine in the mountains at which I had encountered the hyena, I again experienced a shock as of a galvanic battery, the sense of weight, of volition, of substance, returned. I became my original self, and bent my steps eagerly homeward—but the past had not lost the vividness of the real—and not now, even for an instant, can I compel my understanding to regard it as a dream."

"Nor was it," said Templeton, with an air of deep solemnity, "yet it would be difficult to say how otherwise it should be termed. Let us suppose only, that the soul of the man of to-day is upon the verge of some stupendous psychal discoveries. Let us content ourselves with this supposition. For the rest I have some explanation to make. Here is a watercolor drawing, which I should have shown you before, but which an unaccountable sentiment of horror has hitherto prevented me from showing."

We looked at the picture which he presented. I saw nothing in it of an extraordinary character, but its effect upon Bedloe was prodigious. He nearly fainted as he gazed. And yet it was but a miniature portrait—a miraculously accurate one, to be sure—of his own very remarkable features. At least this was my thought as I regarded it.

"You will perceive," said Templeton, "the date of this picture—it is here, scarcely visible, in this corner—1780. In this year was the portrait taken. It is the likeness of a dead friend—a Mr. Oldeb—to whom I became much attached at Calcutta, during the administration of Warren Hastings. I was then only twenty years old. When I first saw you, Mr. Bedloe, at Saratoga, it was the miraculous similarity which existed between yourself and the painting which induced me to accost you, to seek your friendship, and to bring about those arrangements which resulted in my becoming your constant companion. In accomplishing this point, I was urged partly, and perhaps principally, by a regretful memory of the deceased, but also, in part, by an uneasy, and not altogether horrorless curiosity respecting yourself.

"In your detail of the vision which presented itself to you amid the hills, you have described, with the minutest accuracy, the Indian city of Benares, upon the Holy River. The riots, the combat, the massacre, were the actual events of the insurrection of Cheyte Sing, which took place in 1780, when Hastings was put in imminent peril of his life. The man escaping by the string of turbans was Cheyte Sing himself. The party in the kiosk were sepoys and British officers, headed by Hastings. Of this party I was one, and did all I could to prevent the rash and fatal sally of the officer who fell, in the crowded alleys, by the poisoned arrow of a Bengalee. That officer was my dearest friend. It was Oldeb. You will perceive by these manuscripts," (here the speaker produced a note-book in which several pages appeared to have been freshly written,) "that at the very period in which you fancied these things amid the hills, I was engaged in detailing them upon paper here at home."

In about a week after this conversation, the following paragraphs appeared in a Charlottesville paper:

"We have the painful duty of announcing the death of Mr. Augustus Bedlo, a gentleman whose amiable manners and many virtues have long endeared him to the citizens of Charlottesville.

"Mr. B., for some years past, has been subject to neuralgia, which has often threatened to terminate fatally; but this can be regarded only as the mediate cause of his decease. The proximate cause was one of especial singularity. In an excursion to the Ragged Mountains, a few days since, a slight cold and fever were contracted, attended with great determination of blood to the head. To relieve this, Dr. Templeton resorted to topical bleeding. Leeches were applied to the temples. In a fearfully brief period the patient died, when it appeared that in the jar containing the leeches, had been introduced, by accident, one of the venomous vermicular sangsues which are now and then found in the neighboring ponds. This creature fastened itself upon a small artery in the right temple. Its close resemblance to the medicinal leech caused the mistake to be overlooked until too late.

"N. B. The poisonous sangsue of Charlottesville may always be distinguished from the medicinal leech by its blackness, and especially by its writhing or vermicular motions, which very nearly resemble those of a snake."

I was speaking with the editor of the paper in question, upon the topic of this remarkable accident, when it occurred to me to ask how it happened that the name of the deceased had been given as Bedlo.

"I presume," I said, "you have authority for this spelling, but I have always supposed the name to be written with an e at the end."

"Authority?—no," he replied. "It is a mere typographical error. The name is Bedlo with an e, all the world over, and I never knew it to be spelt otherwise in my life."

"Then," said I mutteringly, as I turned upon my heel, "then indeed has it come to pass that one truth is stranger than any fiction—for Bedloe, without the e, what is it but Oldeb conversed! And this man tells me that it is a typographical error."

Published on April 18, 2015 09:00

April 11, 2015

April 4, 2015

A Rattlesnake in the Grass

The naturalist Charles Waterton, who wandered through British Guiana and Brazil in the early 1800s, tells of this close encounter:

Six or seven blackbirds, with a white spot betwixt the shoulders, were making a noise and passing to and fro on the lower branches of a tree in an abandoned, weed-grown orange-orchard. In the long grass underneath the tree apparently a pale green grasshopper was fluttering, as though it had got entangled in it. When you once fancy that the thing you are looking at is really what you take it for, the more you look at it the more you are convinced it is so. In the present case this was a grasshopper beyond all doubt, and nothing more remained to be done but to wait in patience till it had settled, in order that you might run no risk of breaking its legs in attempting to lay hold of it while it was fluttering--it still kept fluttering; and having quietly approached it, intending to make sure of it --behold, the head of a large rattlesnake appeared in the grass close by: an instantaneous spring backwards prevented fatal consequences. What had been taken for a grasshopper was, in fact, the elevated rattle of the snake in the act of announcing that he was quite prepared, though unwilling, to make a sure and deadly spring. He shortly after passed slowly from under the orange-tree to the neighbouring wood on the side of a hill: as he moved over a place bare of grass and weeds he appeared to be about eight feet long; it was he who had engaged the attention of the birds and made them heedless of danger from another quarter: they flew away on his retiring.

Above: A severed rattle in a human hand. Photo by Parker Grice.

Published on April 04, 2015 09:00

March 28, 2015

Scenes from a Bait Dock in San Diego

Published on March 28, 2015 09:00