Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 7

February 10, 2024

In memory of our Kaali/Mother/Prada (2008/9 – Feb 6, 2024)

(Our Kaali, aged between 15 and 16, died after old-age-related deterioration that had carried on for several months, even years. Here's a wholly inadequate tribute)

--------------

For the longest time, we had called her “the mother” – an unintentionally mystical-sounding form of address, as if we were referring to the Holy Mother or some such divinity, though that thought hadn’t crossed our minds. (Mata Kali in her most ferocious form…maybe.) More to the point, we sometimes called her “Chotu’s mother” or “Chotu’s mom” – Chotu being her increasingly obese and dumb-looking son, probably the only surviving member of her litter, from whom she was inseparable: right from the time they came together into our lives in late 2011, until his death, likely of a heart ailment, in 2018.

For the longest time, we had called her “the mother” – an unintentionally mystical-sounding form of address, as if we were referring to the Holy Mother or some such divinity, though that thought hadn’t crossed our minds. (Mata Kali in her most ferocious form…maybe.) More to the point, we sometimes called her “Chotu’s mother” or “Chotu’s mom” – Chotu being her increasingly obese and dumb-looking son, probably the only surviving member of her litter, from whom she was inseparable: right from the time they came together into our lives in late 2011, until his death, likely of a heart ailment, in 2018. “Chotu and the mother” – a classic case of the patriarchy decreeing a woman’s identity in relation to a man. But in the years after Chotu went, she morphed into the generic “Kaali” – something I still regret a little, since I would have liked her to be distinguished from the many other black street dogs, the Kaalis and Kaalus, named by other people, whom I have known. (In the last few months alone, I have written obits for two of those.)

When I wrote a little about *this* Kaali – in her own voice – in an essay for the anthology

The Book of Dog

, I designated her the dog who had no name, and recounted how we had briefly toyed with calling her Prada (only because Chotu was a lovable Gucci – as in a gucci-coochie-pie – and Prada was the harsher-sounding name that suited her). When I watched the horror/historical-fiction series The Terror in 2018, I thought of naming her Tuunbaq after the monster in that show – she was still the bane of many newcomers to our lane, and over the years we had often had to compensate courier boys, maids and others who came wailing to our door with bleeding ankles. Inside the house, she complained and muttered and squinted like a canine Lalita Pawar, even wailing in indignation if she thought one of us was scolding Chotu or coming too close to him. There were many name possibilities.

When I wrote a little about *this* Kaali – in her own voice – in an essay for the anthology

The Book of Dog

, I designated her the dog who had no name, and recounted how we had briefly toyed with calling her Prada (only because Chotu was a lovable Gucci – as in a gucci-coochie-pie – and Prada was the harsher-sounding name that suited her). When I watched the horror/historical-fiction series The Terror in 2018, I thought of naming her Tuunbaq after the monster in that show – she was still the bane of many newcomers to our lane, and over the years we had often had to compensate courier boys, maids and others who came wailing to our door with bleeding ankles. Inside the house, she complained and muttered and squinted like a canine Lalita Pawar, even wailing in indignation if she thought one of us was scolding Chotu or coming too close to him. There were many name possibilities.But Kaali she stayed. It seemed most convenient (and I hadn’t yet made acquaintance with many other black dogs as I would do from the pandemic years onward).

In that Book of Dog piece, I had also touched on how many different types of relationships it is possible to have with dogs, across the continuum from street animal to house pet. With the “part-time dog” – part home, part street, in varying degrees – being the trickiest. Well, Kaali Ma was the towering example of that variety. For the first few years that she was part of my life, not only was she a very independent, full-time street dog, but I wasn’t even the primary caregiver for her and her son, and had minimal interaction with them: my wife Abhilasha (perhaps feeling the absence of our Foxie who had moved almost completely to my mother’s flat) began feeding them once a day near the gate of our building, fielded most of the neighbours’ complaints for a few weeks, and then started bringing them inside our flat just for 5-10 minutes each day so they could eat and go back down – she also arranged for their sterilization operations, a necessary step that if I recall right also led to the first time that they spent a few hours inside the house (carefully restricted to one room), since we had to monitor their healing after the operation. A photo from that time below, Chotu in the foreground, Kaali at back – one of the rare pics we have of them together.

In that Book of Dog piece, I had also touched on how many different types of relationships it is possible to have with dogs, across the continuum from street animal to house pet. With the “part-time dog” – part home, part street, in varying degrees – being the trickiest. Well, Kaali Ma was the towering example of that variety. For the first few years that she was part of my life, not only was she a very independent, full-time street dog, but I wasn’t even the primary caregiver for her and her son, and had minimal interaction with them: my wife Abhilasha (perhaps feeling the absence of our Foxie who had moved almost completely to my mother’s flat) began feeding them once a day near the gate of our building, fielded most of the neighbours’ complaints for a few weeks, and then started bringing them inside our flat just for 5-10 minutes each day so they could eat and go back down – she also arranged for their sterilization operations, a necessary step that if I recall right also led to the first time that they spent a few hours inside the house (carefully restricted to one room), since we had to monitor their healing after the operation. A photo from that time below, Chotu in the foreground, Kaali at back – one of the rare pics we have of them together. Resistant as I am to sweeping pronouncements, Kaali was in many ways the dog with the most distinct, versatile personality that I have known up-close. Or just the most personality, period. Even in the early years, before I had much to do with her or Chotu, I would tell Abhilasha I much preferred The Mother because she had vitality – unlike her “bhondu” boy (bhondu being an inside reference, it was what my alpha-male maamu had always called *me*).

Resistant as I am to sweeping pronouncements, Kaali was in many ways the dog with the most distinct, versatile personality that I have known up-close. Or just the most personality, period. Even in the early years, before I had much to do with her or Chotu, I would tell Abhilasha I much preferred The Mother because she had vitality – unlike her “bhondu” boy (bhondu being an inside reference, it was what my alpha-male maamu had always called *me*). Personality, personality, personality all over – much more than the Samuel L Jackson character in Pulp Fiction could have imagined when he said that line about personality going a long way. She was the feistiest, the most expressive, the most fearless. (For comparison, the two dogs I have been closest to in a parental way – Foxie and Lara – were, respectively, very introverted and very nervous.) From her full-throated singing as accompaniment to Abhilasha’s practice (music teachers, hearing Kaali in the background on Zoom videos, would in all seriousness hold her up as an example to emulate, noting her control over sur and taal. “She is a true Rasika”, my friend Karthika Nair – who knows a good deal about poetry, performance and artistic rigour – remarked after seeing a video) to her playful way of pouncing, panther-like, on a calcium bone I had thrown out for her – or, if she was seated and it was within arm’s reach, crooking her paw (often unnecessarily, more as a dramatic gesture than a practical one) to grab it and draw it towards her, like a dog from a picture-book story, or like Macbeth reaching for the dagger of the mind: “Come, let me clutch thee.”

Looking back now, I still marvel at how much on the periphery of my life Kaali and Chotu were for the first few years they were with us; marvel at how, despite ours being a fairly small, compact flat, they never even got to see the little balconies next to the rooms for years. (Kaali would later spend a lot of time in the drawing-room balcony in her old age.) When they did start spending more time indoors, they weren’t allowed inside the living area, were mostly restricted to a room, and were very well-behaved about this.

This means that in my head – even now – when I think about the period between June 2012 (when my Foxie died, aged just four) and mid-2015, when we adopted puppy Lara, I think of myself as dog-less (and this was the time when I managed to work on the Hrishikesh Mukherjee book and also get some of my most prolific writing done as a columnist and reviewer). Chotu and Chotu’s mother were very much around during that time, but there wasn’t much responsibility attached to them. Also, as relations between Abhilasha and me began to get strained in the year after Foxie’s death, I may have felt a tiny bit of resentment (mixed up with the vague fondness) about these dogs who weren’t really “my” dogs, spending so much time in the house.

There is no point overanalysing along those lines, but it’s certainly true that I never came close to thinking of them as *children* whom I loved, like I did with Foxie and do with Lara – there wasn’t any comparable physical closeness, no cuddling or sleeping on the same bed; anyway, when Kaali came into our lives she was already an adult dog with an almost-adult son. The most intimate contact I had with her and Chotu was on the occasions when I had to pluck what seemed like dozens of ticks of all sizes out of their ears and back during the summers. And even with that proximity, I don’t recall feeling the need to pet or stroke them. This began to change, very gradually, after Chotu went – and especially in the last 3-4 years: first, as Kaali became an almost round-the-clock companion to Abhilasha during the lockdown months (when my attentions were largely on the dogs around my mother’s flat and on the streets), and then in late 2021 when her walking problems became more pronounced and an X-ray disclosed that an incurable joint issue – one paravet called it a form of "bone cancer" – had taken root. Around that point I took over her feeding full-time, changing her diet to the food that was already being made for Lara and the other dogs in my other house, and giving her the daily medicines she needed for her joint problem and for numerous other issues she developed along the way.

This began to change, very gradually, after Chotu went – and especially in the last 3-4 years: first, as Kaali became an almost round-the-clock companion to Abhilasha during the lockdown months (when my attentions were largely on the dogs around my mother’s flat and on the streets), and then in late 2021 when her walking problems became more pronounced and an X-ray disclosed that an incurable joint issue – one paravet called it a form of "bone cancer" – had taken root. Around that point I took over her feeding full-time, changing her diet to the food that was already being made for Lara and the other dogs in my other house, and giving her the daily medicines she needed for her joint problem and for numerous other issues she developed along the way.

My routine became organized around her – even being out of town for a couple of days meant having to give detailed instructions to our domestic staff. In her last two years, my driver Mohan or I would accompany her whenever she needed to go downstairs, even though she was never leashed. (The big epiphany for me had happened one night when, looking down from my balcony shortly after letting Kaali out, I heard whining from the end of the lane and realised that for the first time ever, *she* was being bullied by a couple of dogs whose territory she had confidently crossed into. I had to go downstairs and get her to emerge from the car she had hidden under. Such a thing would have been unimaginable a few years earlier when she was in her pomp, and the scourge of every other dog – and a few humans – in our lane.) She had always loved car drives anyway, and had this unnerving habit of randomly jumping into an auto-rickshaw if it stopped on the road near where she is (and then sitting elegantly in it, as if waiting for the driver to get on with it) – but taking her for a short morning drive around the block became a new ritual in her old age. And in the final couple of months, as one dire diagnosis followed another – intense diabetes, necessitating two insulin shots a day; liver and kidney failure – I was carrying all 40 kg of her up and down most of the stairs as it had become almost impossible for her to negotiate them. Sleeping on a couch very close to her bed, I would feel reassured at night when she was snoring peacefully; feel stressed when I heard her getting up and shifting around uncomfortably, or drinking more water than she should be.

And in the final couple of months, as one dire diagnosis followed another – intense diabetes, necessitating two insulin shots a day; liver and kidney failure – I was carrying all 40 kg of her up and down most of the stairs as it had become almost impossible for her to negotiate them. Sleeping on a couch very close to her bed, I would feel reassured at night when she was snoring peacefully; feel stressed when I heard her getting up and shifting around uncomfortably, or drinking more water than she should be.

At the start of this month, a cloud hung over my Jaipur lit-fest trip, which had been planned months ahead: I made the decision to leave on the scheduled day only after a long phone conversation with our vet, who told me it was very probable that if given electrolytes daily through a drip, she would stay alive and reasonably comfortable for the two-and-a-half days I was away. Even so, I had a terrible, sleepless night in Jaipur on the 3rd, calling Abhilasha to check at 4 AM, looking at various permutations of flight bookings, convinced I would have to fly back to Delhi for a cremation and then try to get back to Jaipur in time for my session.

Kaali waited, though. Wagged her tail when she heard my voice when I walked through the door. Continued to deteriorate otherwise, being unable to retain the water she was so thirsty for, unable to get in the right positions for her toilet. And on the 6th evening, with the gentle encouragement of a vet who almost never encourages euthanasia, it was time to take a call. In the past few years, I have taken other dogs to be put to sleep (including another old black dog, another “Kaali”, who was Lara’s mother – and quite possibly the mother of this Kaali too). But this time was different, more difficult, since it was the first time I was doing it for a dog I had become really close to and spent many years with. And yet, when it happened – calmly, peacefully – there was a strange feeling of satisfaction. This whole process – looking after an old dog round the clock, dealing with the trials and challenges of age, all heading up to the inevitable moment of letting go – felt like the sort of closure we hadn’t got when Foxie died on another vet’s table when we were completely unprepared for it on June 16, 2012, still the worst day of my life.

In the past few years, I have taken other dogs to be put to sleep (including another old black dog, another “Kaali”, who was Lara’s mother – and quite possibly the mother of this Kaali too). But this time was different, more difficult, since it was the first time I was doing it for a dog I had become really close to and spent many years with. And yet, when it happened – calmly, peacefully – there was a strange feeling of satisfaction. This whole process – looking after an old dog round the clock, dealing with the trials and challenges of age, all heading up to the inevitable moment of letting go – felt like the sort of closure we hadn’t got when Foxie died on another vet’s table when we were completely unprepared for it on June 16, 2012, still the worst day of my life.

When Kaali was cremated at Sai Ashram, Chhatarpur, a few feet away from a tombstone that had Foxie’s birth and death dates on it, it struck me that though they had never really known each other, Kaali must have been very close to Foxie in age: they were probably born just a few weeks or months apart. And apart from everything else Kaali gave us over the years, she had given us this opportunity – so badly missed and regretted on an earlier occasion – to celebrate and participate in a full life. Her ashes are buried in a little site right next to Fox's grave, which feels apt.

**********

There is much more to say about her, many other memories – and if I get around to doing a monograph about the dogs in my life, she will be an anchoring presence in it – but for now here are a few photos/videos.

Posing with her “bestie”

Singing and contemplating

The balcony, discovered and enjoyed very late in life

The balcony, discovered and enjoyed very late in life

Smiling wistfully at the remembered scent of courier-boy blood

Objects in the rear-view mirror...

With Mishra ji, one of our lane's residents who must be the only one around who remembers Kaali when she was a pup and still talked to her as if she was one (and she tolerated it!)

Rediscovering her youth briefly after becoming very fond of a young boy dog - there was an age difference of around 80 years between them in dog-years, but romance knows no borders etc.

A rare trip out of Saket - when she came and visited the Panchshila Park house in which I grew up, shortly before it was demolished for reconstruction.

Guardian of gate and door

January 27, 2024

Apsara descending: In praise of Vyjayanthimala

(Wrote this tribute piece a while back. Money Control published it yesterday after Vyjayanthimala was given a Padma Vibhushan)

----------------

The first time I really noticed Vyjayanthimala was during a 1980s family getaway in Ludhiana when some of the older people insisted on watching Naya Daur on videocassette. I was 11 and not too interested in much of the film, even the exciting climactic race, but I registered the pretty heroine singing “Maang ke saath tumhara” to Dilip Kumar on the horse-cart – seemingly the epitome of demure non-urban Indian womanhood of the 1950s.

I didn’t realise it then, but it came as a shock when I did realise it, maybe a few months later: this sweet-looking village belle was the same actress in Raj Kapoor’s opus Sangam, all chic and modern – and sexually desirous – in the “Budha Mil Gaya” song; and in a swimsuit in “Bol Radha Bol”.  Naya Daur and Sangam were made only six or seven years apart, and there is a small similarity in Vyjayanthimala’s function in them – in both, she is the object of desire for two friends, which causes some emotional friction – but in my mind the two films barely occupied the same universe. And for a long time, as I became sporadically exposed to old Hindi cinema, this remained the Vyjayanthimala dichotomy in my head: the old-world version in a black and white film, and the bolder, more assertive version from a bright colour movie just a few years later. The examples changed over the years – Devdas versus Jewel Thief, Madhumati versus Prince – but the dichotomy remained.

Naya Daur and Sangam were made only six or seven years apart, and there is a small similarity in Vyjayanthimala’s function in them – in both, she is the object of desire for two friends, which causes some emotional friction – but in my mind the two films barely occupied the same universe. And for a long time, as I became sporadically exposed to old Hindi cinema, this remained the Vyjayanthimala dichotomy in my head: the old-world version in a black and white film, and the bolder, more assertive version from a bright colour movie just a few years later. The examples changed over the years – Devdas versus Jewel Thief, Madhumati versus Prince – but the dichotomy remained.

However, despite her relatively “modern” look in films like Sangam and Prince, and her ability to be convincing in such set-ups and costumes, on the whole Vyjayanthimala still feels like a denizen of an older time in cinema – compared to some of her contemporaries. There are two reasons for this. One is, simply, that she retired very early. Hard as it is to believe, her last film – Ganwaar – was released in 1970, more than half a century ago.

In comparison, actresses like Nutan and Waheeda Rehman continued to work in the 1970s and 1980s, even opposite younger leading men like Amitabh Bachchan – before going on to play mother to those same heroes. That never happened with Vyjayanthimala (though this may be a good place to remember that she was offered the role of the soon-to-be-iconic mother in Deewaar). If she began her career very young – as a teenager in the early 1950s – she was still youthful, barely in her mid-thirties, when she ended it. And so, in the mind’s eye, she is permanently located in the 1950s and 1960s.

The other reason why Vyjayanthimala seems to belong to a more distant past than some of her peers is her acting style, which was rooted in the mannerisms of a classical dancer, and in the expression of bhava and rasa. This is something that fans of naturalistic screen acting often have little patience with; it represents a different sort of prowess from the one showed by, again, Nutan and Waheeda Rehman – who are the two go-to names when one speaks of great Hindi-film actresses of that era. The ones deemed “natural” and “restrained”.

In fact, around the time that I reluctantly watched Naya Daur as a 1980s child, I was a fan of – and had a slight crush on – Meenakshi Seshadri, without ever realising how much of a Vyjayanthimala “type” she was. Though Seshadri – like Vyjayanthimala – was capable of subtle performances when directed accordingly, in her default mode her eyes always seemed to be moving even when she was doing straight “prose” scenes (and even in a video interview I once saw with candid footage of her playing with children outside her building). They were both very attractive and sensual, but also mannered and theatrical in the way that performers trained in classical dance sometimes were.

Perhaps this is one reason why there was something so intense and interesting – even poignant – about Vyjayanthimala’s pairing with Dilip Kumar, the determinedly understated actor who had brought a modern, non-theatrical sensibility to Hindi cinema. They were such different types, yet they made for one of our finest romantic teams ever, working well together in a number of varied films, their mutual affection always palpable. In Gunga Jumna, speaking in the Awadhi dialect, they both also got to operate outside their comfort zones. The tempestuousness of their  work in that film (including the scene where Kumar’s Gunga inadvertently strikes Vyjayanthimala’s Dhanno as she tries to remove a bullet from his shoulder) makes for a fine contrast with their gentle banter in Paigham, which includes the beautifully performed scene where Kumar tries to make Vyjayanthimala jealous by talking about one of his past romances.

work in that film (including the scene where Kumar’s Gunga inadvertently strikes Vyjayanthimala’s Dhanno as she tries to remove a bullet from his shoulder) makes for a fine contrast with their gentle banter in Paigham, which includes the beautifully performed scene where Kumar tries to make Vyjayanthimala jealous by talking about one of his past romances.

And then there is the 1968 Sunghursh, loosely adapted from a Mahasweta Devi novel which centred on the courtesan Laila-e-Aasmaan – the character who would be played by Vyjayanthimala in the film. The screen version drastically reduced Laila’s importance, which creates a strange narrative tension within the film: this is one of Vyjayanthimala’s most intriguing performances, Sunghursh feels most alive when she is on screen, her character is the story’s moral centre, a mirror reflecting what is going on around her. And yet her screen time is limited and fragmented, and the film ties itself up in knots by focussing on macho feuds, with much showy posturing by a large male cast including Dilip and Sanjeev Kumar, and Balraj Sahni.

Two years earlier, though, Vyjayanthimala had played another courtesan in a film where she was allowed a bigger stage to herself – the title role in the period epic Amrapali – and this is probably my favourite of her performances. It is a gorgeous-looking film (available in very good prints), she looks lovely in it, and the nature of the role and the ancient setting provide the perfect stage for her to show off her range as a classical dancer. Much like Vyjayanthimala herself, Amrapali is an emancipated performer who dances for the pleasure of others as well as for self-expression. There are wonderfully choreographed and shot sequences like the dance challenge that ends with Amrapali being anointed nagarvadhu or royal courtesan; or "Neel Gagan ki Chhaon Mein", where the mood and tempo of the scene moves from sorrow to exhilaration.  Vyjayanthimala at her best seemed of another world, well-suited to playing an apsara in a celestial court, expressing desire openly, unconstrained by societal dictates. She gets to do all of that in this film, and it is not surprising that its commercial failure is usually seen as the big disappointment that led her to end her movie career early, much like a Menaka heading back to Indra’s kingdom after briefly gracing the world of humans.

Vyjayanthimala at her best seemed of another world, well-suited to playing an apsara in a celestial court, expressing desire openly, unconstrained by societal dictates. She gets to do all of that in this film, and it is not surprising that its commercial failure is usually seen as the big disappointment that led her to end her movie career early, much like a Menaka heading back to Indra’s kingdom after briefly gracing the world of humans.

January 13, 2024

Chandler, Karna, and emotional armour (or, a New York yankee in King Dhritarashtra’s court)

(from my Economic Times column. This is a condensed version of an essay I am writing for my “life as a movie-watcher” book)

-------------------

What is the difference between a tragic anti-hero from a great Indian epic and a wisecracking young New Yorker from a popular sitcom? Among many possible answers: only one of them has a laugh track accompanying his life.

But what might be common to these two characters?  Quite possibly, nothing at all. Or nothing that would make sense to anyone but me. But here’s my glib-sounding answer: the emotional kavacha. The armour that protects you from the world, hiding your vulnerability below a covering of (take your pick) toughness, or nastiness… or goofy, laugh-track-accompanied jokes.

Quite possibly, nothing at all. Or nothing that would make sense to anyone but me. But here’s my glib-sounding answer: the emotional kavacha. The armour that protects you from the world, hiding your vulnerability below a covering of (take your pick) toughness, or nastiness… or goofy, laugh-track-accompanied jokes.

Matthew Perry, who died in October, was a great favourite of mine – going back to the early years of this millennium when I watched every Friends episode multiple times as the show was telecast daily on two Indian channels – but if it has taken me this long to write about him it isn’t because I was coming to terms with loss. I just grabbed this pretext to binge-re-watch Friends instead, and to remember a time when the sarcastic Chandler Bing became the last of a series of lonesome types whom I strongly related to – characters encountered between childhood and my twenties, across literature and film.

The first of those was Karna in the Mahabharata, which is where the kavacha comes in. As a young reader when I first became obsessed with the luckless Karna, I wasn’t thinking about subtext – but I may have intuitively grasped that the divine armour, attached to his body until he cuts it away in one of the epic’s most stirring passages, had a symbolic function too. At any rate I understood Karna’s anger and resentment towards those who knew their place in the world and were comfortable in their own (standard-issue) skin. And I wasn’t surprised when, many years later, I read the first analyses of the armour as emotional cover, protecting him not just from physical weapons but from the world’s barbs – while also adding to his defensiveness, helping him nurture a sense of persecution. And how a major growth in character occurs around the time he rids himself of this albatross, opening up and accepting his destiny.

All this sounds solemn, but whenever I pictured Karna in my head I saw him as a sarcastic man, capable of being very cutting, and genuinely funny at times. I felt this fellow had to have a sense of humour – something like the sardonic quality that Bachchan brought to some of his angry-young-man roles. But I rarely if ever saw such a Karna in the many Mahabharata books I read (or in the TV show): those either turned him maudlin, on the cusp of weepy self-pity, or (in the conventional tellings where the Kauravas epitomized evil) a bad guy who was maybe somewhat less bad than the others.

I was well into adulthood when Friends entered my orbit, but Chandler Bing would fill this humour gap with his protective kavacha (“Back then I used humour as a defence mechanism. Thank god I don’t do *that* anymore”).  To repeat: I know not much connects Chandler and Karna (well, they both have parent issues. One doesn’t know who his progenitors are, the other has Kathleen Turner for a dad). But at different points in my life, and in broadly comparable ways, they became people to identify with, helping me articulate things about my inner world and my ways of dealing with the terrifying outside world. I didn’t fully appreciate Chandler at first: when I had only watched snippets of Friends on TV before I began watching the show properly, he came across as the least personable, the loudest, the most dependent on what one sometimes sees as facile, broad comedy. But soon I saw that his exaggerated, hysterical comedy was central to his function as a Greek chorus. In some other ways, he was the most poised and responsible of the six friends – despite being set up from the start as the guy who keeps making jokes which the others tolerate or roll their eyes at in the way that an adult might be indulgent of a prattling child. (The implication almost being that they could, if they chose to, say equally funny things, but were too mature for this. Utter nonsense.)

To repeat: I know not much connects Chandler and Karna (well, they both have parent issues. One doesn’t know who his progenitors are, the other has Kathleen Turner for a dad). But at different points in my life, and in broadly comparable ways, they became people to identify with, helping me articulate things about my inner world and my ways of dealing with the terrifying outside world. I didn’t fully appreciate Chandler at first: when I had only watched snippets of Friends on TV before I began watching the show properly, he came across as the least personable, the loudest, the most dependent on what one sometimes sees as facile, broad comedy. But soon I saw that his exaggerated, hysterical comedy was central to his function as a Greek chorus. In some other ways, he was the most poised and responsible of the six friends – despite being set up from the start as the guy who keeps making jokes which the others tolerate or roll their eyes at in the way that an adult might be indulgent of a prattling child. (The implication almost being that they could, if they chose to, say equally funny things, but were too mature for this. Utter nonsense.)

Over the course of a 236-episode situation comedy, it is inevitable that we will see each of these six protagonists at their silliest, most immature, most vulnerable at some point or the other – and that character arcs won’t be consistent over 10 years, they will be subordinate to the creation of funny “situations”. But with Chandler (and maybe even Perry), there is a sense that the immaturity is mainly performative, always with a tinge of self-awareness. And unlike my childhood hero, he doesn’t need to lose the armour to become more human. You can drily comment on the action around you, even while being part of it.

Or as Chandler might say, “BING!! part of it.”

(Related posts: Friends and masala; Karna in Mrityunjay)

January 12, 2024

In praise of Destry Rides Again

I have done very little movie -watching in the past two months, but I ended the year with the wonderful, hard-to-classify 1939 film Destry Rides Again – a Comedy-Drama-Musical-Western(!) with the unusual but very effective pairing of Marlene Dietrich and James Stewart. Technically this is a Western (about the “cleaning up” of a corrupt and violent town called Bottleneck), but that doesn’t begin to describe its quirkiness. Its leading man is a deputy sheriff who drinks milk and refuses to carry a gun (at least, for a while). The longest brawl in the film involves two women (this is 15 years before Joan Crawford and Mercedes McCambridge faced off in Johnny Guitar). There is much loony dialogue, and the characters – both the heroes and the villains – behave very differently from the usual Western archetypes.

I have done very little movie -watching in the past two months, but I ended the year with the wonderful, hard-to-classify 1939 film Destry Rides Again – a Comedy-Drama-Musical-Western(!) with the unusual but very effective pairing of Marlene Dietrich and James Stewart. Technically this is a Western (about the “cleaning up” of a corrupt and violent town called Bottleneck), but that doesn’t begin to describe its quirkiness. Its leading man is a deputy sheriff who drinks milk and refuses to carry a gun (at least, for a while). The longest brawl in the film involves two women (this is 15 years before Joan Crawford and Mercedes McCambridge faced off in Johnny Guitar). There is much loony dialogue, and the characters – both the heroes and the villains – behave very differently from the usual Western archetypes. Here is an example of a studio-era film where all the constituent parts come together brilliantly, under the direction of someone (George Marshall) who doesn’t have a reputation as an auteur or a “personal filmmaker”. One tends to associate such films with reliable solidity (Casablanca might be a major example), as opposed to zaniness, but Destry Rides Again is very much the latter. While it isn’t a revisionist Western in the sense that some films from the 1950s and 1960s onward were, it is offbeat and free-flowing (in comparison, John Ford’s Stagecoach, made the same year, seems traditional and hemmed-in) – a sort of masala movie with bawdy comedy and serious drama (there are a couple of very moving scenes, and beautifully shot close-ups) and music and madness, and even a touch of police procedural.

You haven’t experienced Wild West whimsy until you’ve heard Jimmy Stewart (with his fiercest expression and fastest drawl) say the line: “Now the next time you fellas start any of this here promiscuous shooting around the streets, you’re going to land in jail. Understand?” Or when Mischa Auer (one of many super character actors in this film) unnecessarily says: “Yes Mon Commandant. I am a courier, fast as a bolt of lightning, silent as the night itself” before heading off to perform an important errand for Destry. You can completely see why Mel Brooks was influenced by this film when making Blazing Saddles.

You haven’t experienced Wild West whimsy until you’ve heard Jimmy Stewart (with his fiercest expression and fastest drawl) say the line: “Now the next time you fellas start any of this here promiscuous shooting around the streets, you’re going to land in jail. Understand?” Or when Mischa Auer (one of many super character actors in this film) unnecessarily says: “Yes Mon Commandant. I am a courier, fast as a bolt of lightning, silent as the night itself” before heading off to perform an important errand for Destry. You can completely see why Mel Brooks was influenced by this film when making Blazing Saddles.  In my view, this film also played as big a part in the creation of the Stewart screen persona as the much better known Mr Smith Goes to Washington did the same year. Meanwhile, Dietrich had been a big star for years, but was being labelled “box-office poison” at this time, and this is one of her most fun roles: yee-haw-ing away in her opening scene in a rambunctious saloon, cat-fighting, singing. (That same year, 1939, Ninotchka was famously promoted as a film where Greta Garbo laughed – and a remote and icy screen goddess was humanised – but Destry Rides Again also gives us a more accessible Marlene Dietrich, compared to the parts she did for Josef von Sternberg earlier in the decade.)

In my view, this film also played as big a part in the creation of the Stewart screen persona as the much better known Mr Smith Goes to Washington did the same year. Meanwhile, Dietrich had been a big star for years, but was being labelled “box-office poison” at this time, and this is one of her most fun roles: yee-haw-ing away in her opening scene in a rambunctious saloon, cat-fighting, singing. (That same year, 1939, Ninotchka was famously promoted as a film where Greta Garbo laughed – and a remote and icy screen goddess was humanised – but Destry Rides Again also gives us a more accessible Marlene Dietrich, compared to the parts she did for Josef von Sternberg earlier in the decade.)So much fun, especially if you’re interested in the history of the Western and the many avatars it took before it settled into the self-consciously revisionist version of the late 1960s and beyond. I try to avoid making recommendations, since I don’t presume to know anyone else’s tastes, but do give this a try. The first 15 minutes or so is chaos, but it settles into a proper storyline after Destry arrives. For those who haven’t watched much from 1930s Hollywood, this is also a useful introduction to performers like Brian Donlevy (who played the lead in Preston Sturges’s wonderful The Great McGinty), Una Merkel, Charles Winninger, and of course Mischa Auer.

I have shared a good print of Destry Rides Again on my film group. If anyone here wants it, let me know.

December 13, 2023

On thinking you know a film despite not watching it (or watching it so long ago that your brain has repackaged it)

(Wrote this for my Economic Times column)

(Wrote this for my Economic Times column)---------------------

If you spend time reading film-related discourse on social media, you’re probably fed up with the endless echo-chamber discussions (both for and against) around Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Animal. Without watching the film, I feel like I have had it assessed for me through every available lens – along a continuum from virtue-signalling to vice-celebrating. So I’ll spare you my thoughts about the agonising and the exulting, except to say: I find it problematic (to use a cherished “liberal” word) when people unshakably make up their minds about a film they haven’t watched yet, and even dissuade others from watching it. Or when they are convinced that a film can only be one thing, hence worthy of contempt – and that anyone who engages with it on another level is in some sense morally compromised, or deluded.

One of the radical points that come up in my conversations with students is that one should ideally experience a work – read a novel beginning to end, watch a whole film, not just its trailer – before venturing an opinion. (In a recent class we spoke about cases – common in the OTT age – of viewers, including professional critics on tight deadlines, forming judgements about a series after watching just an episode or two, without taking the time to discover the arc of a character or situation.) This also involves engaging with many different things – including what you fear may discomfit you – and can result in a special type of joy: being surprised by your own response to a work, even finding a dimension in yourself that you hadn’t fully tapped into. An aunt – rigid in her tastes, very hung up on “realism” in art – was once forced by friends to accompany them for a Sanjay Leela Bhansali opus, and went grumbling, convinced she would hate it based on what she had seen of his work earlier. She came out smitten, gushing about the beauty of the film’s world-creation, and couldn’t stop talking about it for a few days.

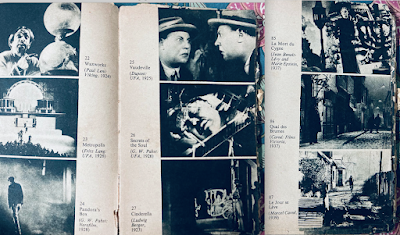

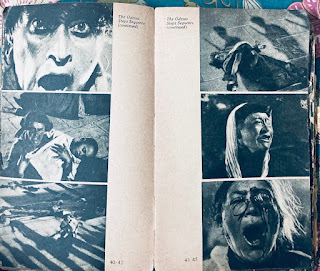

Now, a confession: despite this preaching, there are some films – including iconic ones – that I haven’t watched but still have a version of in my head. As an adolescent developing an interest in old cinema, one of my prized books was Roger Manvell’s 1946 Film, and through its pages – notably a thick image inset filled with black-and-white stills – I first formed impressions of what certain films looked like. There were striking double-exposure shots from German Expressionist classics like The Last Laugh; fragments of the famous Odessa Steps sequence in Battleship Potemkin; images that emphasized giant shadows (Ivan the Terrible), or people caught in a moment of contemplation (Wendy Hiller playing Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion). A photo of a man on a bicycle in the French film Le Jour se Leve was so evocative, I had it in my head as I cycled through the little lanes around my DDA flats in Saket, imagining a giant camera was recording me from above.

Now, a confession: despite this preaching, there are some films – including iconic ones – that I haven’t watched but still have a version of in my head. As an adolescent developing an interest in old cinema, one of my prized books was Roger Manvell’s 1946 Film, and through its pages – notably a thick image inset filled with black-and-white stills – I first formed impressions of what certain films looked like. There were striking double-exposure shots from German Expressionist classics like The Last Laugh; fragments of the famous Odessa Steps sequence in Battleship Potemkin; images that emphasized giant shadows (Ivan the Terrible), or people caught in a moment of contemplation (Wendy Hiller playing Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion). A photo of a man on a bicycle in the French film Le Jour se Leve was so evocative, I had it in my head as I cycled through the little lanes around my DDA flats in Saket, imagining a giant camera was recording me from above.  Thirty years later, thinking of some of these films, I think first of those images in an ancient, crumbling book – or maybe a fleeting scene, a dramatic moment in isolation. And if I watch (or re-watch) them, I am often surprised. In a previous column I mentioned being stirred by David Lean’s Brief Encounter – something I hadn’t expected because in my head this was a cool, reserved, very British film of a certain time, with even deep love being expressed through little nods and surreptitious glances over cups of tea. And it did have scenes like that, but there was a powerful, aching tremor below the film’s surface that made it in its own way just as passionate a love story as anything that an Imtiaz Ali (or a Vanga!) might helm.

Thirty years later, thinking of some of these films, I think first of those images in an ancient, crumbling book – or maybe a fleeting scene, a dramatic moment in isolation. And if I watch (or re-watch) them, I am often surprised. In a previous column I mentioned being stirred by David Lean’s Brief Encounter – something I hadn’t expected because in my head this was a cool, reserved, very British film of a certain time, with even deep love being expressed through little nods and surreptitious glances over cups of tea. And it did have scenes like that, but there was a powerful, aching tremor below the film’s surface that made it in its own way just as passionate a love story as anything that an Imtiaz Ali (or a Vanga!) might helm. There are disappointments too: I went into a restored-print screening of the 1956 Dev Anand-starrer CID having not watched the film before (or not having a clear memory of it), and imagining it as a Hindi-film take on American noir, inevitably with songs and masala elements but at least with a sturdy suspenseful plot – and was annoyed to find a disjointed work that didn’t capture the brooding darkness of its source genre (despite game attempts by the young Waheeda Rehman and Mehmood).

And there are films that you once knew very well, but which your brain has transformed into something else over time. I recently re-watched two Anthony Hopkins starrers that were an important part of my early-90s viewing life, and was intrigued to find that while Hannibal Lecter’s prison cell in Silence of the Lambs wasn’t quite the rat-infested dungeon-sewer I

remembered, the big country house in which Stevens the butler serves in Remains of the Day was not as gleaming as I had thought; this didn’t feel like a sterile, too-polished Merchant-Ivory film (like, say, Howards End which had also starred Hopkins and Emma Thompson) but was more in keeping with the theme of decay that runs through Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel.

remembered, the big country house in which Stevens the butler serves in Remains of the Day was not as gleaming as I had thought; this didn’t feel like a sterile, too-polished Merchant-Ivory film (like, say, Howards End which had also starred Hopkins and Emma Thompson) but was more in keeping with the theme of decay that runs through Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel. In my memory all these years, the aesthetics of these movies were very different. Watching now, it felt like parts of Darlington Hall, with its gloomy passageways and crumbling plaster, would make an acceptable dwelling for Lecter and cohort. Maybe, to a degree, cannibals and animals are a construct of our fevered minds, and the butler really did it after all.

November 28, 2023

Catching up with AKB

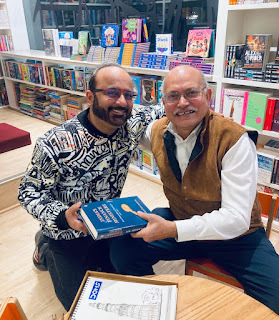

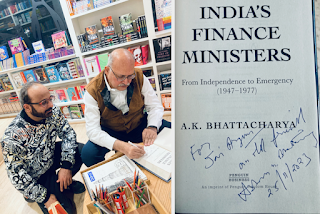

A very pleasing encounter at Kunzum, Greater Kailash-2, a few days ago: I met AK Bhattacharya (or AKB as we always refer to him), the Business Standard editorial director, after what must have been 15 years. From this person flowed many of the kindnesses that enabled me to get started on a freelance career in 2006. He was the big boss who made me the offer I couldn’t refuse - a retainership with Business Standard that would allow me to work independently and write for others - but even before that, at a more personal and friendly level, he had been very encouraging about my blog and would often come by my desk to mention a post he had liked (or something he wanted to correct me about, mainly pertaining to Satyajit Ray). Given the big hierarchical gap between us in office, such interactions were unusual, but he pulled them off warmly and without fuss - and he greeted me much the same way at the bookshop yesterday (where I also got my signed copy of his new book about India’s finance ministers between 1947-77).

A very pleasing encounter at Kunzum, Greater Kailash-2, a few days ago: I met AK Bhattacharya (or AKB as we always refer to him), the Business Standard editorial director, after what must have been 15 years. From this person flowed many of the kindnesses that enabled me to get started on a freelance career in 2006. He was the big boss who made me the offer I couldn’t refuse - a retainership with Business Standard that would allow me to work independently and write for others - but even before that, at a more personal and friendly level, he had been very encouraging about my blog and would often come by my desk to mention a post he had liked (or something he wanted to correct me about, mainly pertaining to Satyajit Ray). Given the big hierarchical gap between us in office, such interactions were unusual, but he pulled them off warmly and without fuss - and he greeted me much the same way at the bookshop yesterday (where I also got my signed copy of his new book about India’s finance ministers between 1947-77).  Great to see him looking as fit and spry as I remembered, and to find that he often uses the metro for traveling (something that many of the much younger people I know regard with disdain, as if it lowers their status or some such). We’ll catch up again soon, possibly in his lair, the Business Standard office...

Great to see him looking as fit and spry as I remembered, and to find that he often uses the metro for traveling (something that many of the much younger people I know regard with disdain, as if it lowers their status or some such). We’ll catch up again soon, possibly in his lair, the Business Standard office...

November 4, 2023

A brief encounter with classic films, on a big screen

(my latest Economic Times column)

(my latest Economic Times column)-------------------

Most film buffs who are invested in old cinema (and by “old”, dear post-millennials, I don’t mean the hazy mists of time just before the advent of Christopher Nolan) know that we have mostly viewed classic films in conditions they weren’t made to be watched in. On small, flat screens, with countless distractions. But it is one thing to know this, quite another to be confronted firsthand with the repercussions. A proper, big-screen viewing of an iconic film in a restored print can blow your circuits and cause you to rethink everything about your movie-watching history, as happened with me during the recent Delhi screenings organised by Shivendra Singh Dungarpur and the Film Heritage Foundation team.

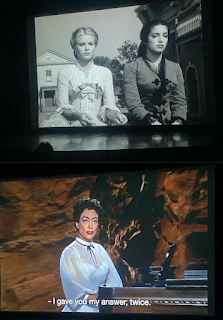

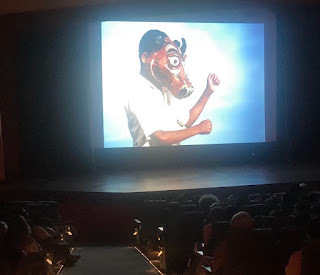

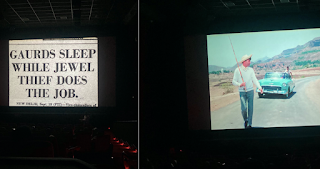

It began with the Dev Anand centenary in September – and the chance to see Guide and Jewel Thief in plush multiplexes – and continued at the India Habitat Centre and India International Centre. Watching Apocalypse Now: The Final Cut, G Aravindan’s folklore classic Kummatty and even Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (which I am not a big fan of generally) in these conditions was an incredibly intense experience. The wonderful, dialogue-less sequence in Kummatty where the bogeyman leads the children in a dance before transforming them into animals had a hypnotic quality that made it seem a wholly different film from the one I had seen just a year ago.

It began with the Dev Anand centenary in September – and the chance to see Guide and Jewel Thief in plush multiplexes – and continued at the India Habitat Centre and India International Centre. Watching Apocalypse Now: The Final Cut, G Aravindan’s folklore classic Kummatty and even Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (which I am not a big fan of generally) in these conditions was an incredibly intense experience. The wonderful, dialogue-less sequence in Kummatty where the bogeyman leads the children in a dance before transforming them into animals had a hypnotic quality that made it seem a wholly different film from the one I had seen just a year ago.An important value-addition to the screenings were inputs by guests such as Lee Kline and Karen Stetler of the Criterion Collection, who have been involved in many restorations and were in a position to offer background information and insights. They recounted anecdotes and ethical dilemmas: is it okay, for instance, to change the look of an old film in restoration, even at the director’s bequest? (What if a director originally wanted the film to look a certain way but couldn’t do it for budgetary or technical reasons, and now has a belated opportunity to restore his vision – but at the cost of changing the look of a work that viewers have known for decades?) “You almost have to become a referee in these cases,” Kline said, mentioning how Theo Angelopoulos had wanted to make little colour corrections in a film during a restoration. Or how there was a brief proposal – eventually shot down – to turn the last two shots of Francis Ford Coppola’s black-and-white film Rumble Fish into colour, to achieve a particular artistic effect. They also spoke about the trickiness of restoring a film from a culture they didn’t know much about, such as the 1977 Senegalese film Ceddo, made by the late Ousmane Sembène. “We were looking for help from anyone since there was so little information available,” Kline said, “It was important to know the difference between one African skin tone and another. Or to be told – I wouldn’t have known this – that in Senegal the sky is almost never blue.”

My one reservation: during Kline’s introduction to Douglas Sirk’s tempestuous 1956 drama Written on the Wind, I felt he was being patronising about melodrama as a form. “Please keep in mind that you watch a film like this for fun, to laugh a bit at the characters – don’t take it seriously,” he said. This felt bizarre, especially addressed to an Indian audience made up of people who had grown up with mainstream Hindi cinema (even if many of us are sheepish about that filmic language too) – it could be that Kline was being defensive, or trying to keep our expectations low, but either way it wasn’t required, for Written on the Wind got the reception it richly deserved. I had watched it a decade ago, but this was another animal altogether. The brilliant compositions, the use of colour, Sirk’s relentlessly tracking camera which brought a kinetic energy to so many dramatic scenes, and yes, the turbulence of the emotions – all of this was heightened and made more urgent in a dark hall. The texture of the images felt different, a little grainier (in a good way) than the cool, smooth digital images most of us are so used to – you could appreciate details such as the vein popping on an anguished character’s forehead.

My one reservation: during Kline’s introduction to Douglas Sirk’s tempestuous 1956 drama Written on the Wind, I felt he was being patronising about melodrama as a form. “Please keep in mind that you watch a film like this for fun, to laugh a bit at the characters – don’t take it seriously,” he said. This felt bizarre, especially addressed to an Indian audience made up of people who had grown up with mainstream Hindi cinema (even if many of us are sheepish about that filmic language too) – it could be that Kline was being defensive, or trying to keep our expectations low, but either way it wasn’t required, for Written on the Wind got the reception it richly deserved. I had watched it a decade ago, but this was another animal altogether. The brilliant compositions, the use of colour, Sirk’s relentlessly tracking camera which brought a kinetic energy to so many dramatic scenes, and yes, the turbulence of the emotions – all of this was heightened and made more urgent in a dark hall. The texture of the images felt different, a little grainier (in a good way) than the cool, smooth digital images most of us are so used to – you could appreciate details such as the vein popping on an anguished character’s forehead.  I felt similarly while watching another classic, made in a more restrained mode but also building towards moments of high emotion, all the more effective for having been suppressed: David Lean’s Brief Encounter, about a fleeting extramarital relationship, told mainly from the woman’s viewpoint. As a teen viewer I had crushed on the prim Celia Johnson, but hadn’t been well-placed to properly understand the two forty-ish protagonists and the intolerable situation they find themselves in after falling in love. I understood much better now, and this was aided enormously by the scale of the viewing. The conventional view is that it’s the later Lean films – the epics such as Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago – that need a huge screen, but Brief Encounter – so full of stolen glances and anxious gestures – is a different type of big-screen masterpiece: as its tone moves from stiff-upper-lip reserve, and the need to keep feelings under check, to something more desperate, the film becomes tense and alarming, almost like a Hitchcock thriller.

I felt similarly while watching another classic, made in a more restrained mode but also building towards moments of high emotion, all the more effective for having been suppressed: David Lean’s Brief Encounter, about a fleeting extramarital relationship, told mainly from the woman’s viewpoint. As a teen viewer I had crushed on the prim Celia Johnson, but hadn’t been well-placed to properly understand the two forty-ish protagonists and the intolerable situation they find themselves in after falling in love. I understood much better now, and this was aided enormously by the scale of the viewing. The conventional view is that it’s the later Lean films – the epics such as Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago – that need a huge screen, but Brief Encounter – so full of stolen glances and anxious gestures – is a different type of big-screen masterpiece: as its tone moves from stiff-upper-lip reserve, and the need to keep feelings under check, to something more desperate, the film becomes tense and alarming, almost like a Hitchcock thriller.  To see those magnificent close-ups of Johnson’s troubled face, and then close-ups of another troubled character in a very different genre of film – Gary Cooper as the beleaguered lawman without support in High Noon, or Joan Crawford as the saloonkeeper Vienna in Johnny Guitar – was to be reminded of what film-watching can be like when you do it right, and how vital and relevant and dangerous an 80-year-old film can still be in these conditions. But of course, soon after this I was on my way home in the metro, watching as people “consumed content” on their mobile screens – ravenous zombies on a Halloween night.

To see those magnificent close-ups of Johnson’s troubled face, and then close-ups of another troubled character in a very different genre of film – Gary Cooper as the beleaguered lawman without support in High Noon, or Joan Crawford as the saloonkeeper Vienna in Johnny Guitar – was to be reminded of what film-watching can be like when you do it right, and how vital and relevant and dangerous an 80-year-old film can still be in these conditions. But of course, soon after this I was on my way home in the metro, watching as people “consumed content” on their mobile screens – ravenous zombies on a Halloween night. October 28, 2023

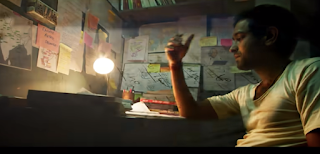

Heart, soul, and a terrific Vikrant Massey performance: on 12th Fail

(About a new film I hadn’t expected to like much – thought it would be another tedious exercise in well-intentionedness – but was completely engrossed by. Wrote this review )

----------- My first all-encompassing thought about Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s 12th Fail, once the closing credits began, was that here is a film which is all heart. Now, ordinarily, that wouldn’t be grounds enough for approval (for me at least) – if anything, the statement could imply a snarky addendum. (To paraphrase a scene from a movie that’s very different in tone and subject, the recent thriller Chup about a serial killer targeting critics: “This film has its heart in the right place; unfortunately the other organs are scattered all over”.)

My first all-encompassing thought about Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s 12th Fail, once the closing credits began, was that here is a film which is all heart. Now, ordinarily, that wouldn’t be grounds enough for approval (for me at least) – if anything, the statement could imply a snarky addendum. (To paraphrase a scene from a movie that’s very different in tone and subject, the recent thriller Chup about a serial killer targeting critics: “This film has its heart in the right place; unfortunately the other organs are scattered all over”.)

With 12th Fail, though, the other organs are not disorganised or scattered. They are packed neatly together, each fulfilling its given function, in the service of an engrossing, forthright story based on Anurag Pathak’s book about a “12th fail” village lad who gives the IPS exams – repeatedly, and against the odds.

At the surface level, this is a straightforward, message-oriented story: Manoj (Vikrant Massey), a young man from a Chambal village, is studying for the UPSC but is also part of a schooling system where the teachers facilitate cheating so the school can maintain its pass percentage – until one day an honest policeman comes in and shakes things up (at risk to himself, given that the local vidhayak is overseeing the school, and the children of Chambal dacoits supposedly study in it!). Manoj – briefly taken into custody for running a “jugaad” shuttle service with his brother – gets gooey-eyed after an encounter with this DSP, and is inspired by the strange possibility of truthfulness. Soon he travels to Gwalior (where his fortunes are almost scuppered by someone else’s dishonesty) and then, with the help of a new friend Pandey (Anantvijay Joshi), to Delhi where he sets his sights on the IPS exam – despite being warned that the percentages are against him (only 25 or so selected out of a lakh or more aspirants).

In telling this story, 12th Fail covers some familiar tropes: the kinship of underprivileged strugglers who stand by each other through heartaches, a loving grandmother with pension saved up in a trunk beneath her bed, the hard-working protagonist who does menial labour during the day and studies at night. While Manoj begins a sweet, tentative romance with a more well-off Mussoorie girl named Shradha (Medha Shankar), his own family struggle back in the village but keep their spirits high.  So, yes, this film IS all heart; a nit-picker might say that given the very real problems faced by Manoj, there is a little too much cheeriness, a few too many helpful and well-intentioned characters (starting with a restaurant owner in Gwalior who gives Manoj a free meal despite the latter insisting that he must earn it). And yet, 12th Fail – through the integrity of the writing and acting – avoids being schmaltzy in a bad way. Much of its power comes from Massey’s anchoring performance (and one realises, looking at his sincere, sometimes awkward smile, how effective he might have been in the Hrithik Roshan part in Super 30 if that film had chosen to operate in a less starry meter).

So, yes, this film IS all heart; a nit-picker might say that given the very real problems faced by Manoj, there is a little too much cheeriness, a few too many helpful and well-intentioned characters (starting with a restaurant owner in Gwalior who gives Manoj a free meal despite the latter insisting that he must earn it). And yet, 12th Fail – through the integrity of the writing and acting – avoids being schmaltzy in a bad way. Much of its power comes from Massey’s anchoring performance (and one realises, looking at his sincere, sometimes awkward smile, how effective he might have been in the Hrithik Roshan part in Super 30 if that film had chosen to operate in a less starry meter).

The narrative of 12th Fail stresses the goodness of people – or their potential for goodness – even in very tough situations; the power of solidarity, even the idealistic sort that goes “Yeh hum sab ki ladaai hai”. As one important character, a benevolent tutor who never gets to clear the main exam himself, puts it, there may be crores of “bhed-bakriyan”, sheep and goats, from all over India coming for these exams, but if even one of them makes it, that is a victory for all the underdogs. This can sound like feel-good mush, but the film also, briefly at least, depicts the bitterness and angst of the sheep who don’t make it, and how close friendships and important relationships can be damaged at the walls where result sheets are pinned up. It is aware that the fates of the “good people”, such as the incorruptible DSP Dushyant whose example sets Manoj on the right path, are precarious.

The story is also a testament to the plurality of this country: starting with a panoramic view of that verdant Chambal (Pandey’s voiceover grimly reminding us that this is still in the popular imagination daku terrain), then homing down to a young man studying on the roof of a little house – before moving to large, daunting, overpopulated Delhi where hordes of people buzz about like flies in front of the dazzled Manoj’s eyes. It is about the unequal opportunities for education, and the very different experience of the education system, for people from different backgrounds: about those of us who can take opportunities for granted versus those for whom even completing basic schooling is a challenge (even when they are from supportive, caring families). And how cut off the IPS interviewers – sitting primly in their sterile rooms – can be from grass-roots realities.

“I’m 71 years old, but I still press the ‘restart’ button every day of my life,” Vidhu Vinod Chopra said after a recent Delhi screening, alluding to a word that plays a pivotal role in motivating Manoj. 12th Fail seems a like a modest, low-key work coming from the man who gave us Parinda, Khamosh and Mission Kashmir, but it has its own layers of complexity – its structure is such that one is always aware of the countless other stories that don’t have happy endings. The film may posit that Manoj’s journey represents a validation for lakhs of other “bakray” (and one hopes that in real life people like him do retain enough integrity and the common touch to provide voice to the voiceless), but the tone remains grounded and self-aware. Here is a feel-good film which, even as it builds towards a deeply emotional climax, somehow doesn’t play like a facile feel-good film.

October 25, 2023

Kaalu, in remembrance (???? - 2023)

True enough – this Kaalu (another generic name, given to him by guards before I became acquainted with him) was not an easy dog to get along with. He was thin and frail-looking (a condition that had worsened in the past few months – though his appetite was good, I think he may have succumbed to a version of the stomach/intestinal condition that took my Foxie), but many people in the colony, even animal-carers, were wary of his temper; there was a time a few years ago when his potential for aggression had caused me a lot of trouble. Which made it flattering that he seemed, dare I say it, fond of me in his distant, suspicious way, and even let me pet him for a second or three while I was giving him dry food or biscuits. (I often saw something resembling softness in his eyes, which many people I know would scarcely believe – and, I found this weirdly moving and comforting, if he saw me walking towards the colony gate en route to the shops outside or the PVR Anupam complex, he would follow me closely for some distance even when there clearly wasn’t anything in it for him.) But he was also fully capable of snapping or snarling if my hand got too close to his ears to check for a possible wound. Medicating him was a painfully tough task, and the couple of occasions when I absolutely had to call my paravet friends to treat a maggot infection, it could take us hours just to get him into a sheltered space, restrain and muzzle him. He came to Golf View Apartments around five years ago (after having been driven away from another Saket colony, I was reliably told – there are indications that he had a sad history, which may have contributed to his personality issues) and at some point settled near my building, making friends – against the odds – with another recently arrived dog whom we call Pandey. Pandey is beige, and bigger and sturdier than Kaalu was, but a complete scaredy-cat otherwise, and something just happened to click between them: they were usually together these past few years, running around in the colony or sleeping on my stairway (the last three winters my house help and I put out boris/mattresses for them), and Kaalu’s presence seemed to give Pandey confidence. Personality issues apart, Kaalu wasn’t the sort of dog that neutral observers would take to – too emaciated, not “good-looking”, not enough clearly visible features if you gave him a casual glance from a distance – and I saw him on the receiving end of human hostility a few times over the years: little stones being thrown, sticks being waved threateningly (including by our colony guards at the behest of the RWA, until I intervened and gave a few of those old imbeciles a talking to). On one occasion he was following me around during my evening walk when I saw a vegetable vendor hit him hard, with a stick, on his bony and delicate back — only because he had been sniffing around outside his shop. He’s gone now, and I will miss him a lot despite us never having been on anything close to cuddling terms. The main solace is that I could play a part in giving him a decent quality of life for his last few years. The thing to do now is to make lonely, nervous Pandey feel as comfortable as possible in his partner’s absence. Starting with the firecracker days that lie ahead. (Last year, on Diwali night, I kept both Kaalu and Pandey in my mother’s flat for several hours until the noise outside died down, and I remember looking at them and thinking how much like house dogs even the most feral “strays” could become once you gave them a safe space to settle down in. Kaalu didn’t get any more such opportunities, but Pandey will this year too.) (Photos here: Kaalu atop a car, looking healthier than he had been in recent months, and under a table on Diwali night; on the stairs, and posing with Uday Bhatia's Satya book; Kaalu and Pandey together in the park, on a car, and on our stairway)

True enough – this Kaalu (another generic name, given to him by guards before I became acquainted with him) was not an easy dog to get along with. He was thin and frail-looking (a condition that had worsened in the past few months – though his appetite was good, I think he may have succumbed to a version of the stomach/intestinal condition that took my Foxie), but many people in the colony, even animal-carers, were wary of his temper; there was a time a few years ago when his potential for aggression had caused me a lot of trouble. Which made it flattering that he seemed, dare I say it, fond of me in his distant, suspicious way, and even let me pet him for a second or three while I was giving him dry food or biscuits. (I often saw something resembling softness in his eyes, which many people I know would scarcely believe – and, I found this weirdly moving and comforting, if he saw me walking towards the colony gate en route to the shops outside or the PVR Anupam complex, he would follow me closely for some distance even when there clearly wasn’t anything in it for him.) But he was also fully capable of snapping or snarling if my hand got too close to his ears to check for a possible wound. Medicating him was a painfully tough task, and the couple of occasions when I absolutely had to call my paravet friends to treat a maggot infection, it could take us hours just to get him into a sheltered space, restrain and muzzle him. He came to Golf View Apartments around five years ago (after having been driven away from another Saket colony, I was reliably told – there are indications that he had a sad history, which may have contributed to his personality issues) and at some point settled near my building, making friends – against the odds – with another recently arrived dog whom we call Pandey. Pandey is beige, and bigger and sturdier than Kaalu was, but a complete scaredy-cat otherwise, and something just happened to click between them: they were usually together these past few years, running around in the colony or sleeping on my stairway (the last three winters my house help and I put out boris/mattresses for them), and Kaalu’s presence seemed to give Pandey confidence. Personality issues apart, Kaalu wasn’t the sort of dog that neutral observers would take to – too emaciated, not “good-looking”, not enough clearly visible features if you gave him a casual glance from a distance – and I saw him on the receiving end of human hostility a few times over the years: little stones being thrown, sticks being waved threateningly (including by our colony guards at the behest of the RWA, until I intervened and gave a few of those old imbeciles a talking to). On one occasion he was following me around during my evening walk when I saw a vegetable vendor hit him hard, with a stick, on his bony and delicate back — only because he had been sniffing around outside his shop. He’s gone now, and I will miss him a lot despite us never having been on anything close to cuddling terms. The main solace is that I could play a part in giving him a decent quality of life for his last few years. The thing to do now is to make lonely, nervous Pandey feel as comfortable as possible in his partner’s absence. Starting with the firecracker days that lie ahead. (Last year, on Diwali night, I kept both Kaalu and Pandey in my mother’s flat for several hours until the noise outside died down, and I remember looking at them and thinking how much like house dogs even the most feral “strays” could become once you gave them a safe space to settle down in. Kaalu didn’t get any more such opportunities, but Pandey will this year too.) (Photos here: Kaalu atop a car, looking healthier than he had been in recent months, and under a table on Diwali night; on the stairs, and posing with Uday Bhatia's Satya book; Kaalu and Pandey together in the park, on a car, and on our stairway)

(Related posts: Lara's brother Sona; little Kaali)

(Related posts: Lara's brother Sona; little Kaali)

September 26, 2023

Watching Dev Anand on the big screen, in 2023

(Wrote this experiential piece – based on going for some of the Dev Anand centenary screenings – for Money Control)

(Wrote this experiential piece – based on going for some of the Dev Anand centenary screenings – for Money Control)-------------

In conversations about the best-looking leading men in Hindi cinema, a few names repeatedly come up, from the young Prithviraj Kapoor to Dharmendra and Vinod Khanna in their prime to Hrithik Roshan today. Ten years ago, during a screening of the 1951 Baazi at the Centenary Film Festival in Delhi, I witnessed a sight that could make all those discussions irrelevant. The film’s protagonist Madan, a small-time gambler about to be led into an upper-crust world of crime, is glimpsed from the back during a game of dice. He throws a double-six, the camera pans up to show him in full glory – and the entire auditorium bursts into cheers and whoops. Because here is the young Dev Anand, looking just a bit disreputable, peaked cap on head, cigarette in mouth. And completely breath-taking.

At a festival that was all about nostalgia – about older viewers coming to relive memories of the films and stars they had loved in their youth – there were many enthusiastic audience responses; but nothing that quite compared with this moment in terms of the electricity it generated in the hall.

If the Dev Anand of the 1950s – in films like Baazi, Jaal, CID, Taxi Driver – was pure gorgeousness in stark black and white, the later, Eastmancolor avatars had a slightly different texture of charm and confidence: in films like Guide and Jewel Thief and Johny Mera Naam, we can see that version of Dev, still lighting up the screen, not having yet fully succumbed to the self-congratulatory mannerisms that would annoy many viewers in the last two or three decades of his career. Careful restorations of these three films, along with the much earlier CID, were screened in multiplexes across the country this weekend, creating more gasps of admiration – and a few inevitable titters of amusement. I went for Guide, CID and Jewel Thief, and was thrilled by the quality of the restorations (though the hall I watched Guide in had messed up the aspect ratio in projection, turning the print into an exact square; other friends, watching in other cities, had similar stories).

If the Dev Anand of the 1950s – in films like Baazi, Jaal, CID, Taxi Driver – was pure gorgeousness in stark black and white, the later, Eastmancolor avatars had a slightly different texture of charm and confidence: in films like Guide and Jewel Thief and Johny Mera Naam, we can see that version of Dev, still lighting up the screen, not having yet fully succumbed to the self-congratulatory mannerisms that would annoy many viewers in the last two or three decades of his career. Careful restorations of these three films, along with the much earlier CID, were screened in multiplexes across the country this weekend, creating more gasps of admiration – and a few inevitable titters of amusement. I went for Guide, CID and Jewel Thief, and was thrilled by the quality of the restorations (though the hall I watched Guide in had messed up the aspect ratio in projection, turning the print into an exact square; other friends, watching in other cities, had similar stories). The first thing that happened when I entered the hall: a man in his seventies, at least, standing in the aisle and about to shuffle in to find his seat, caught my eye. With my white hair and beard, in a dimly lit hall, he probably thought of me as someone of his vintage, and he smiled widely. It was a very specific smile of kinship and knowingness directed at a stranger – can you believe we are here watching this film in this setting, after all these decades, it seemed to say. It was one of those rare times when I haven’t minded being mistaken for someone much older.

There were, as expected, many other old people in the hall for the screenings – some of them seemed fairly independent, even coming in groups and chattering away; others were brought by younger family members, a few of them even moving with the aid of foldable walkers; I sympathised when I saw them going painfully, slowly to the washrooms during the interval, where they had to wait a few minutes because of the queues. But while the films were actually on, there was a palpable energy in the dark hall – I doubt anyone regretted having come, regardless of physical inconvenience.

During Guide – the most respectable and canonised of these four films – viewers clapped with reverence after every one of Waheeda Rehman’s dance performances (and, though never a demonstrative viewer myself, I couldn’t help joining in). The responses to the beautifully restored Jewel Thief, one of our finest thrillers, were more extreme and varied: on the one hand, there were gasps of admiration during the film’s many visually beautiful moments, such as the night-time “Rula ke Gaya Sapna” sequence, and Tanuja’s performance of “Raat Akeli Hai”; but on the other hand, viewers clearly also felt liberated enough to laugh at the things they