Barry Hudock's Blog, page 35

January 11, 2013

Pre-orderable

Faith Meets World: The Gift and Challenge of Catholic Social Teaching is now available for pre-order. It’s available (at the links) from Liguori, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or an independent bookseller. Thanks for considering it!

Faith Meets World: The Gift and Challenge of Catholic Social Teaching is now available for pre-order. It’s available (at the links) from Liguori, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or an independent bookseller. Thanks for considering it!

December 31, 2012

Now at Commonweal: my article on one of JP2′s great social encyclicals

Now here’s a personal thrill. Commonweal magazine has posted “True Then, Truer Now,” an article I wrote to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of Pope John Paul II’s encyclical Sollicitudo Rei Socialis. Given Commonweal‘s track record of consistently high-quality exploration of issues facing Catholics today, an always-compelling blog (dotCommonweal, a daily visit for me), and a venerable place in American Catholic history, I’m pleased as can be to find a little place in the journal’s work.

Now here’s a personal thrill. Commonweal magazine has posted “True Then, Truer Now,” an article I wrote to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of Pope John Paul II’s encyclical Sollicitudo Rei Socialis. Given Commonweal‘s track record of consistently high-quality exploration of issues facing Catholics today, an always-compelling blog (dotCommonweal, a daily visit for me), and a venerable place in American Catholic history, I’m pleased as can be to find a little place in the journal’s work.

Sollicitudo stands as a lasting achievement of its remarkable author and as a landmark in the social encyclical tradition. My article points out some distinctive contributions Sollicitudo made and why it remains relevant a quarter century later. Here’s a snippet:

Like the preferential option, the idea of structures of sin represents a dramatic papal appropriation of a concept that had been richly developed in liberation theology. The 1984 CDF document had warned against what it regarded as a too facile integration of Marxist ideology into Catholic political theory by some liberation theologians. The document left many with the impression that the entire project of liberation theology had been officially condemned. On the contrary, a follow-up 1986 document provided a far more positive assessment, acknowledging that “the fight against injustice is meaningless unless it is waged with a view to establishing a new social and political order in conformity with the demands of justice.”

Just over a year later, here was Sollicitudo, a papal encyclical, embracing some of liberation theology’s central themes. In fact, the encyclical includes seven citations from the second CDF document and none from the first. Its closing section includes several references to liberation and the sin and structures of sin that stand in the way of its realization. As Elizabeth Johnson observes in her Quest for the Living God, “Rarely has the core project of a theology been so quickly and widely adopted into mainstream church teaching.”

There’s more. The entire piece is here.

Finally, the anniversary of Sollicitudo offers a great moment to re-read the encyclical itself. It’s here.

Favorites reads of 2012

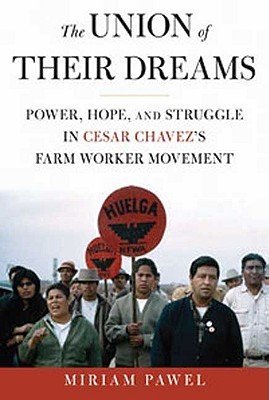

Best book I read during 2012: The Union of Their Dreams: Power, Hope, and Struggle in Cesar Chavez’s Farm Worker  Movement, by Miriam Pawel (Bloomsbury, 2010).

Movement, by Miriam Pawel (Bloomsbury, 2010).

This book tells the story of Chavez and the United Farm Workers organization from the point of view of those who worked closest with Chavez. It offers a more nuanced view than much of the material that has long been available about Chavez and the events in which he played such a central role. The light shed on Chavez and his personality is often but not always positive. What results is an image of him that is more realistic and more human, but just as admirable, perhaps not so much in spite of but because of that fact.

Other big favorites from 2012 reading:

If These Walls Could Talk: Community Muralism and the Beauty of Justice, by Maureen O’Connell (Liturgical Press, 2012)

The Option for the Poor in Christian Theology, edited by Daniel G. Groody (University of Notre Dame, 2007).

(Having been working through much of this year on finishing up my own book, Faith Meets World: The Gift and Challenge of Catholic Social Teaching, most of the reading I did focused on topics related to social justice and Catholic social teaching.)

Favorite novel of 2012: Fragile, by Lisa Unger

December 27, 2012

Martyrdom and the Mass: a fascinating connection

The January 2013 issue of the journal Worship includes an article by Maxwell Johnson that offers some fascinating thinking about the eucharistic prayer of Mass that we hear recited Sunday after Sunday and how it got there in the first place.

The January 2013 issue of the journal Worship includes an article by Maxwell Johnson that offers some fascinating thinking about the eucharistic prayer of Mass that we hear recited Sunday after Sunday and how it got there in the first place.

‘Words of Consecration’

The eucharistic prayer is at the heart of the Mass, “the center and summit of the entire celebration” (as the General Instruction of the Roman Missal puts it). One important part of it is the institution narrative. Addressing God the Father, the priest recites briefly the story of the Last Supper. It goes this way, for example, in Eucharistic Prayer II:

At the time he was betrayed and entered willingly into his Passion, he took bread and, giving thanks, broke it, and gave it to his disciples, saying: ‘Take this, all of you, and eat of it: for this is my Body which will be given up for you.’

In a similar way, when supper was ended, he took the chalice and, once more giving thanks, hegave it to his disciples, saying: ‘Take this, all of you, and drink from it: for this is the chalice of my Blood, the Blood of the new andeternal covenant, which will bepoured out for you and for many for the forgiveness of sins. Do this in memory of me.’

This has long played a crucial and — it was long understood — essential role in the eucharistic prayer. Catholics (for several centuries) have understood it to be the moment in which the sacrament was “confected,” when the body and blood of Jesus truly became present, and without which no sacrament happened. Those words of Jesus as recited by the priest are still often called “the words of consecration.”

So it’s a little amazing that it was almost certainly absent from the eucharistic prayers used in the first three centuries of the life of the Church. There is now nearly a consensus among the liturgical historians about this. Generations of Christians celebrated the Eucharist without ever mentioning those words of Jesus or recounting the story of his leading the the Last Supper.

Indeed, even today the Mass is celebrated without the “words of consecration” by the faithful of the Assyrian Church of the East, which uses a eucharistic prayer that dates from the early days of the Church and so does not include an institution narrative. The Catholic Church formally acknowledges the validity of this Eucharist and permits Catholics of the Chaldean rite to participate in it. (What a strong reminder that we must be very cautious about what we take to be “orthodox” Catholic faith and what we reject as not.)

‘The Cessation of Martyrdom’

All of this is the context, not the point, of Maxwell Johnson’s article in January’s Worship. Johnson (a professor of liturgical studies at Notre Dame) tries to identify one possible reason that the institution narrative came to be included in the eucharistic prayer when it did. He suggests that what brought this development about might well have been the end of the period of severe persecutions of the early Church – the end of the age of martyrdom.

During those early centuries, Johnson explains, the Church’s eucharistic prayers focused a great deal on the nourishment, life, and even immortality that the eucharist provides to Christians. When martyrdom was common, Christians did not need to be reminded that their faith meant sacrifice, even of their very lives. It was all too clear. But by the mid-third century, as the persecutions stopped and Christianity became widely accepted in society, to be a Christian was not so dangerous or demanding; on the contrary, it came to be more an expectation, a matter of course. And, as in our own day (in the western world, anyway), bishops and priests might well have judged that Christians needed to be challenged to take their faith more seriously and live it more fully.

Johnson suggests that this factor may have played an important role in how and why the institution narrative — with Jesus speaking of his followers partaking of his body to be given up and his blood to be shed – worked its way into the eucharistic prayer. He writes:

The sacrifical connotations and implications of adding the narrative of institution to the eucharistic prayer may well be directly related also to the cessation of martyrdom, by emphasizing the very cost of discipleship implied by sharing the cup of Christ in the Eucharist, that is, both the public liturgy [martyrdom] and reception in holy communion of the body and blood of Christ sacrificed!

Making the argument more compelling, Johnson points out that scholars already recognize the end of the age of martyrdom as having had a similar effect on the Church’s practice and theology of baptism. For the first several centuries, baptism was understood primarily as a spiritual re-birth, as a singular moment of becoming a child of God. The primary scriptural passages associated with the sacrament during that time were the accounts of the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan (with the words of the Father coming from heaven, “This is my beloved son”), along with John 3:5. It was only later, in the fourth century, that Paul’s theology of baptism as a dying and rising with Christ (see Romans 6) became a key baptism reference, probably because the faithful needed reminding that being a Christian was (supposed to be) serious business.

Johnson’s article is titled “Martyrs and the Mass: The Interpolation of the Narrative of Institution into the Anaphora.” It provides more supporting argumentation than I note here. It also offers some fascinating background information about the place that devotion to the martyrs played in the early Church that alone makes the article well worth the time.

For ongoing nourishment in liturgical history and theology, there’s no better place to go than the journal Worship.

December 16, 2012

First look at the cover

I was excited to open an email from Liguori Publications yesterday and find this — the cover of the new book, Faith Meets World: The Gift and Challenge of Catholic Social Teaching. (It’s coming April 1, 2013!)

I was excited to open an email from Liguori Publications yesterday and find this — the cover of the new book, Faith Meets World: The Gift and Challenge of Catholic Social Teaching. (It’s coming April 1, 2013!)

My thanks to the talented folks at Liguori for their work on this! It’s exciting to see.

December 10, 2012

A hell of a story: John Courtney Murray

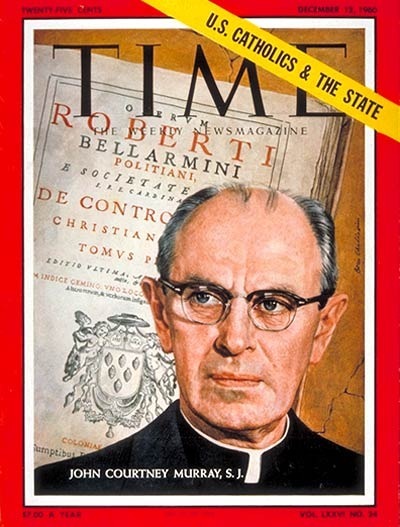

It wa s 52 years ago this week – December 12, 1960 — that Fr. John Courtney Murray, SJ, appeared on the cover of Time magazine. (The cover article is here.) He was in the midst of living a story that is both fascinating and dramatic.

s 52 years ago this week – December 12, 1960 — that Fr. John Courtney Murray, SJ, appeared on the cover of Time magazine. (The cover article is here.) He was in the midst of living a story that is both fascinating and dramatic.

Murray had, over the previous decade and a half, found himself advocating a theological approach to religious freedom that was quite different from what he called “the received opinion” within the Church. But what he called the receieved opinion was seen by many influential Catholic figures as simply the teaching of the Catholic Church and so not to be questioned by one of its own theologians (particularly during the decade of the 1950s). This had culminated, in 1955, in Murray being silenced, forbidden by his superiors within the Jesuit order, under pressure from Rome, to write or publish on the topic. (“You may write poetry,” Murray’s superior had told him when Murray asked about the boundaries of the order.)

But the reigning pope, Pius XII, had died in 1958, and his successor, Pope John XXIII, had already, by the time of the Time cover, announced his intention to convoke the Second Vatican Council. While history records the Council as the moment of Murray’s stunning vindication, neither he nor anyone else within the Church of the time knew it yet in December 1960.

Nor could they have reasonably suspected it. When the Council opened in October 1962, many highly regarded theologians were there as periti (theological experts and advisors) of the bishops who gathered, and many of them would have a powerful influence on the Council’s work. Among the periti was Fr. Joseph Clifford Fenton, who had since 1948 nearly made a career of criticizing Murray’s work on religious freedom. Fenton was called to Vatican II as peritus to one of the most powerful men in Rome, Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, head of the Holy Office (known today as the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith). Murray, on the other hand, was not even invited and stayed home.

How Murray eventually ended up at the Council (a full year later), and how that Council ultimately resulted in the promulgation of Dignitatis Humanae, the Declaration on Religious Freedom, is another fascinating part of the story and (it is probably not an exaggeration to say) an epochal moment in Church history.

The upshot is that Murray’s work was not only not (in the judgement of the Council) contrary to Catholic teaching — as Fenton and Ottaviani insisted it was — but accepted as an authentic development of the tradition that was both faithful to what had come before and attentive to modern understandings of personhood, freedom, and rights. That this could or would be the case was, on December 12, 1960, when Murray’s face appeared on the cover of Time, still far from clear to many watching or participating in this controversy.

I’m working on a book on John Courtney Murray these days, to be published, most likely, in spring 2014. The more I go about my research, digging into archives, perusing personal letters and diaries of Murray, Fenton, and others, and uncovering for myself some of the nearly unknown historical record on all this, the more I find it all to be, quite frankly, a hell of a story. More here, I’m sure, in the months ahead.

December 8, 2012

Talking Eucharist and social justice

Nothing does an author’s heart good — okay, nothing strokes an author’s ego — quite like walking into an undergraduate classroom to see 20 students sitting with his book on their desks in front of them. I had the pleasure on Thursday of visiting the classroom of Fr. Anthony Ruff, OSB, on the St. John’s University campus in Collegeville, with the students of his Initiation and Eucharist course. (In addition to being an associate professor of theology at St. John’s, Fr. Anthony is the moderator of the popular and always interesting Pray Tell blog and the author of Sacred Music and Liturgical Reform: Treasures and Transformations.)

Nothing does an author’s heart good — okay, nothing strokes an author’s ego — quite like walking into an undergraduate classroom to see 20 students sitting with his book on their desks in front of them. I had the pleasure on Thursday of visiting the classroom of Fr. Anthony Ruff, OSB, on the St. John’s University campus in Collegeville, with the students of his Initiation and Eucharist course. (In addition to being an associate professor of theology at St. John’s, Fr. Anthony is the moderator of the popular and always interesting Pray Tell blog and the author of Sacred Music and Liturgical Reform: Treasures and Transformations.)

One of the texts for the course is my The Eucharistic Prayer: A User’s Guide, and Fr. Anthony graciously invited me by to talk about the book and how it came to be written. I enjoyed being able to talk about the contents of the book, including a central theme of the book which has long fascinated me: the Church’s ancient conviction of lex orandi, lex credendi (“the law of prayer is the law of faith”). That is, what we say and do in our liturgy has an awful lot to say about what it is we believe. Indeed, it’s normative: if what we believe doesn’t reflect and conform to the content of our liturgical prayer, we probably need to rethink believing it.

One interesting direction the conversation went was to the connections between the Church’s liturgy and its social teaching. I lamented that too many of us in the Catholic Church have seemingly bought into American political culture and have become convinced that we must line up along one of two mutually exclusive “party lines.” We think we must choose between either being interested and engaged in the Church’s liturgical and sacramental life, its devotions and saints, and a strong attentiveness to (much of) its doctrinal teaching OR in its social concerns and social teachings, its engagement with the world, and the struggle to make society more just and humane, especially for those who have been battered by its injustices.

To my mind, nothing is farther from the truth, and as I mentioned to the students, some of the greatest figures the Church produced in the twentieth century bear witness to the fact. John Paul II, Dorothy Day, and Mother Teresa came immediately to mind. They were each daily Mass-goers throughout their long adult lives and intense in their devotion to the celebration of the Eucharist. But they were also each equally committed to the essential place that a committment to the poor and to social justice must have in Christian living. Indeed, every one of them would have insisted that a committment to one nourishes and sustains a committment to the other.

I might just as well have mentioned other greats from other eras, right from St. Paul at the Church’s origins (who chastised the Christians of Corinth for excluding the poor from their Eucharist, insisting that by that very fact, it was not even a real Eucharist they were celebrating) up through other important figures through century after century who recognized this same reality in their own ways and circumstances.

In a forehead-slapping moment later in the afternoon, it occurred to me how silly it was that I did not mention, as I sat there in a Collegeville classroom, Virgil Michel, OSB. A monk of St. John’s Abbey here in Collegeville (Fr. Anthony’s community now), Michel was a preeminent figure in the liturgical movement of the early twentieth century. It was Michel who brought that movement from Europe and planted it on American shores, where it grew and took on new elements unique to the American context. In fact, Michel played a huge part in imbuing the American liturgical movement with the aspect that was probably most distinctive about it: its intense awareness of the connections between liturgy and social justice. Michel insisted that it’s the liturgy that forms in us the qualities we need to recognize what a just society would look like and to live and work in a way that makes our society more just.

May Virgil Michel forgive me for my oversight. My thanks to Fr. Anthony and his students for their gracious welcome the other day.

December 3, 2012

Benedict brings it up again: a global political authority

“Political Authority and Universal Jurisdiction” is the topic being addressed this week by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, in a 3-day plenary session that opened today. The theme gave Pope Benedict a chance, in his address to the group, to reiterate yet again the Catholic Church’s longtime support for some form of global political authority.

“Political Authority and Universal Jurisdiction” is the topic being addressed this week by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, in a 3-day plenary session that opened today. The theme gave Pope Benedict a chance, in his address to the group, to reiterate yet again the Catholic Church’s longtime support for some form of global political authority.

Though the Catholic News Agency article reporting the talk says this controversial idea has been ”envisioned by two popes” (making reference to Blessed Pope John XXIII alongside Benedict himself), this is understating it. Besides John XXIII and Benedict XVI, Blessed Pope John Paul II and Pope Paul VI also supported the idea prominently. So that’s four popes who have pushed it — every pope of the past half century, in fact (other than the one who only reigned for a month in 1978).

One reason this is especially worth pointing out is that it highlights the way the Catholic idea of subsidiarity has been distorted and misrepresented for political ends lately. Recent vice-presidential candidate Paul Ryan, often referred to as the intellectual leader of the Republican party, made much of his Catholic faith during 2012 and cited it, and in particular its teaching on subsidiarity, in support of his economic policy proposals.

For Ryan, however, subsidiarity is an anti-big government principle, almost a Catholic endorsement of a “government is the problem” approach. It is “really federalism,” he said, and insisted that it supports “not having big government crowd out civic society.”

While subsidiarity certainly can and does mean that many problems should be addressed at local levels by local organizations and governments, it is far from being ”anti-big government.” Subsidiarity says social problems are best addressed and most effectively solved at the lowest level possible and at the highest level necessary. Thus it recognizes that sometimes bigger is better, too. Sometimes, in fact, bigger is essential.

That this more complete understanding of subsidiarity is the authentic (and authentically Catholic) one is made obvious by the fact that the very same popes who have been strident in their support of Catholic social teaching (which includes subsidiarity as an important aspect) and made many strong contributions to its dissemination and development have also been vocal supporters of the development of some form of world political authority.

Their thinking has been that in modern society, which is marked by so many elements that are absolutely global in scope, there will always be some issues that a global political authority can address most effectively. (It was just over a year ago, for example, that the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace called for some form of global financial authority to adequately address the circumstances created by today’s radically global financial markets.)

This is precisely the point that Pope John XXIII made in his 1963 encyclical letter, Pacem in Terris. If subsidiarity were fundamentally opposed to “big government,” what sense would it make for this pope — who produced two landmark soclal encyclicals during a 4-and-a-half-year pontificate — to write (in section 137):

This is precisely the point that Pope John XXIII made in his 1963 encyclical letter, Pacem in Terris. If subsidiarity were fundamentally opposed to “big government,” what sense would it make for this pope — who produced two landmark soclal encyclicals during a 4-and-a-half-year pontificate — to write (in section 137):

“Today the universal common good presents us with problems which are world-wide in their dimensions; problems, therefore, which cannot be solved except by a public authority with power, organization and means co-extensive with these problems, and with a world-wide sphere of activity. Consequently the moral order itself demands the establishment of some such general form of public authority.”

Here, in fact, Good Pope John supported this broader form of government idea specifically in terms of subsidiarity. Pope Paul VI repeated the idea in his 1967 encyclical Populorum Progressio (section 78). Pope John Paul II did it in his Message for the World Day of Peace in 2003. And Pope Benedict XVI did it in his 2009 encyclical Caritas in Veritate (section 67).

(Note that in every case but one here, the teaching is offered not in a relatively obscure Wednesday audience address or homily at Sunday Mass, but in the context of a papal encyclical. When an idea shows up in one of those, it doesn’t get there by accident.)

So it’s not surprising that Pope Benedict once again today put papal support behind the idea.

Pope Benedict brings it up again: a world political authority

“Political Authority and Universal Jurisdiction” is the topic being addressed this week by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, in a 3-day plenary session that opened today. The theme gave Pope Benedict a chance, in his address to the group, to reiterate yet again the Catholic Church’s longtime support for some form of global political authority.

“Political Authority and Universal Jurisdiction” is the topic being addressed this week by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, in a 3-day plenary session that opened today. The theme gave Pope Benedict a chance, in his address to the group, to reiterate yet again the Catholic Church’s longtime support for some form of global political authority.

Though the Catholic News Agency article reporting the talk refers to this controversial idea as one “envisioned by two popes” (making reference to Blessed Pope John XXIII alongside Benedict himself), this is understating the case. Besides John XXIII and Benedict XVI, Blessed Pope John Paul II and Pope Paul VI also supported the idea prominently. So that’s four popes who have pushed it — every pope of the past half century, in fact (other than the one who only reigned for a month in 1978).

One reason this is especially worth pointing out is that it highlights the way that the Catholic idea of subsidiarity has been distorted and misrepresented for political ends lately. Recent vice-presidential candidate Paul Ryan, often referred to as the intellectual leader of the Republican party, made much of his Catholic faith during 2012 and cited it, and in particular the Catholic moral principle of subsidiary, in support of his economic policy proposals.

Ryan, however, presented subsidiarity as an anti-big government principle, as almost a Catholic endorsement of a “government is the problem” approach. It is “really federalism,” he said, and insisted that it supports “not having big government crowd out civic society.”

While subsidiarity certainly can and does mean that many problems should be addressed at local levels by local organizations and governments, it is far from being ”anti-big government.” Subsidiarity says social problems are best addressed and most effectively solved at the lowest level possible and at the highest level necessary. Thus it recognizes that sometimes bigger is better, too. Sometimes, in fact, bigger is essential.

That this more complete understanding of subsidiarity is the authentic (and authentically Catholic) one is made obvious by the fact that the very same popes who have been strident in their support of Catholic social teaching (which includes subsidiarity as an important aspect) and made many strong contributions to its dissemination and development have also been vocal supporters of the development of some form of world political authority.

Their thinking has been that in modern society, which is marked by so many elements that are absolutely global in scope, there will always be some issues that a global political authority can address most effectively. (It was just over a year ago, for example, that the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace called for some form of global financial authority to adequately address the circumstances created by today’s global financial markets.)

This is precisely the point that Pope John XXIII made in his 1963 encyclical letter, Pacem in Terris. If subsidiarity were fundamentally opposed to “big government,” what sense would it make for this pope — who produced two landmark soclal encyclicals during a 4-and-a-half-year pontificate — to write (in section 137):

This is precisely the point that Pope John XXIII made in his 1963 encyclical letter, Pacem in Terris. If subsidiarity were fundamentally opposed to “big government,” what sense would it make for this pope — who produced two landmark soclal encyclicals during a 4-and-a-half-year pontificate — to write (in section 137):

“Today the universal common good presents us with problems which are world-wide in their dimensions; problems, therefore, which cannot be solved except by a public authority with power, organization and means co-extensive with these problems, and with a world-wide sphere of activity. Consequently the moral order itself demands the establishment of some such general form of public authority.”

Here, in fact, Good Pope John supported this broader form of government idea specifically in terms of subsidiarity. Pope Paul VI repeated the idea in his 1967 encyclical Populorum Progressio (section 78). Pope John Paul II did it in his Message for the World Day of Peace in 2003. And Pope Benedict XVI did it in his 2009 encyclical Caritas in Veritate (section 67).

(Note that in every case but one here, the teaching is offered not in a relatively obscure Wednesday audience address or homily at Sunday Mass, but in the context of a papal encyclical. When an idea shows up in one of those, it doesn’t get there by accident.)

So it’s not surprising that Pope Benedict once again today put papal support behind the idea.

December 1, 2012

Three good reads

1. The music star/activist Bono is going out of his way to point out some effective and important work done in recent years by the Catholic Church in pursuit of social justice. It happened thanks largely to the strong leadership of Pope John Paul II, but was undergirded solidly by a century of Catholic social teaching.

1. The music star/activist Bono is going out of his way to point out some effective and important work done in recent years by the Catholic Church in pursuit of social justice. It happened thanks largely to the strong leadership of Pope John Paul II, but was undergirded solidly by a century of Catholic social teaching.

The Catholic News Agency and EWTN report is here. Thanks to Rebecca Hamilton at the always compelling Public Catholic blog for pointing it out.

2. Daniel Nichols (author of Caelum et Terra, one of my very favorite blogs) offers a brief essay on America’s development of the nuclear bomb, hubris, and blasphemy that is like a splash of cold water to the face. I’m glad he mentions consequentialism, because you can’t raise the question of the morality of the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, even among those who consider themselves the strongest of Catholics, without immediately getting arguments that the same people would reject angrily if someone tried to apply parallel reasoning to the use of contraception.

3. Archbishop Charles Chaput offers a challenging reflection on the “flaw in the American gene code” that predisposes us to individualism and consumerism. On the weakening of Catholic life that has resulted, Chaput writes, “American culture is a new kind of mission territory. It’s a cocoon of marketing, entertainment, and manufactured appetites; a narcotic of noise, distraction, and relentless propaganda for self-absorption and confused sexuality. Being in the United States in the weeks before Christmas is an education in what the culture really worships. It worships commerce.”

Some of what Chaput has said in recent months has rubbed me the wrong way at times. This essay — posted at the First Things On the Square blog and originally an address delivered in Peru — is right on the money (so to speak!).