Martin Fone's Blog, page 79

July 28, 2023

Such Bright Disguises

A review of Such Bright Disguises by Brian Flynn – 230709

What a wonderful book. Brian Flynn is never one to follow a tried and tested formula, always willing to shake things up and in his twenty-seventh book in his Anthony Bathurst series originally published in 1941 and reissued by Dean Street Press, he serves up an inverted murder story of sorts. It is great fun, hugely entertaining featuring a deadly love triangle and while not everything is resolved as neatly as it might be, it ranks high up amongst my favourites.

The book is structured in three parts with the first, entitled Hubert, setting the scene and leading up to the first murder, that of the eponymous Hubert, Hubert Grant, a rather pompous bureaucrat whose traits and desire to be the centre of attention has gradually sucked out the life of his marriage to Dorothy. She begins to look for love elsewhere and falls for Laurence Weston, who seems to be not only the antithesis of Hubert but the man of their dreams. They begin a covert relationship and realise, after a particularly awkward and depressing Christmas, that the only way that they will find happiness is for Hubert to be out of the way. Not long afterwards, Hubert is found drowned in what Laurence considers to be the perfect murder.

Part Two, entitled Laurence, describes life after Hubert and how the once idyllic relationship disintegrates through a combination of fear, mistrust, and tragedy. After an appropriate period of mourning Laurence and Dorothy resume their love affair, eventually marrying and moving to the other side of London. However, the dread of discovery is accentuated by the arrival on each public holiday of a different book detailing the crimes, detection, and execution of murderous couples and a note threatening that the couple’s crime will soon be revealed, signed by Harry the Hangman. Dorothy sees visions of Hubert and slowly declines into a form of madness and for all his cleverness, Laurence fears that she will be their weak link and lead to their undoing.

Tragedy also stalks the family. Frances, Dorothy’s beloved child from her first marriage with Hubert, is knocked down at a dangerous crossing and dies while her child with Laurence is born blind. They also have a radio set that has a dodgy switch that means that the signal fades out after a while. On the very same day Dorothy is found strangled at her home and Laurence, after being joined at the table at which he is having lunch in London by a stranger, is poisoned.

Part Three, the shorter of the three parts, is where Bathurst, brought in by his old mucker, Sir Austin Kemble, joins forces with MacMorran of the Yard to solve the mysteries of the three deaths. With his razor-sharp brain Bathurst is able to sort out the wheat from the chaff and put up a plausible theory as to who killed whom and why. It all makes sense, although the identity of the mystery woman who lured Hubert to his death is left hanging. I had my suspicions but it would nice to have them validated.

However, the power of the book is not in the complexity of the plot or in the brilliance of Bathurst’s powers of deduction but in Flynn’s powerful characterisation and description of how the intensity of emotions can be a double-edged sword and the consequences of the rapid descent into paranoia and madness. It is an impressive book and, if you have not sampled Flynn’s murder mysteries, a good place to start.

There is one slight oddity in the text. What we now know as the Second World War is described as the Second German War. Given the text was probably written in 1940, perhaps the term reflects the fact that the conflict had not expanded beyond the confines of Europe. I wonder how common that description was.

July 27, 2023

Forty Spotted Tasmanian Classic Gin

One way to get noticed in the crowded market that has been spawned by the ginaissance is to play up to a national stereotype. Take Australia. We all know that, from a northern hemispherical perspective, it is at the bottom of the world and everything is upside down. Why not take that concept into the bottle design for your gin? This is what Rock Hoedjes, the brains behind Tasmania’s Forty Spotted Gin has done.

The bottle for his Forty Spotted Tasmanian Classic Gin certainly makes an impression on the shelf. Made of clear rounded glass with a geometric design embossed in to it. It makes use of a dark blue on the labelling with white lettering and the central label contains an illustration of a bunch of juniper berries. The most distinctive feature is that the punt, that large indent normally at the bottom of the bottle, is at the top of the bottle and the extremely short neck which leads to a large flat plastic screwcap acts as the base, bearing the legend “From the bottom of the world”. In other words, the bottle appears to be upside down. Whether the joke is restricted to the export market only or is intended for an Aussie audience too, I am not sure.

Not being confident as to the strength of the bottle’s seal once it is opened, I store it with the indent at the bottom, so that it looks like a woman with a rather rounded figure wearing an enormous dark blue hat. Of course, this means the labelling is upside down.

Rock’s distillery takes its name from the forty-spotted pardalote (Pardalotus quadrigentus), one of Australia’s rarest birds which is now only to be found in a few colonies around the south-eastern corner of Tasmania. It is a small bird, about three to four inches long, with black wing feathers with white tips. When the wings are folded the tips of each feather look like dots or spots, although there are nearer sixty than forty on an adult.

The label at the rear tells me in typically forthright Aussie fashion that the approach was to take some superbly matched Tasmanian botanicals, a bunch of juniper, a splash of lime leaf with lemon peel citrus, and you’ve got an exciting dry drink that packs punches of Tasmanian Pepperberry. It’s our classic for a reason”.

The full botanical line up appears to be Tasmanian Pepper berry, which is spicy and tangy, Pepper berry leaf, juniper, coriander seed, ruby grapefruit, bergamot, makrut lime leaf, ruby grapefruit peel, lemon peel, coriander, ginger, and frankincense. The distillation process is a little more complex than the label might suggest, the pepper berries going straight into the pot with the ruby grapefruit, juniper, and coriander while the rest of the botanicals sit in a basket. Once the spirit is suffused with the flavours and scents of the Tasmanian botanicals, it is diluted down to an ABV of 40% using pure Tasmanian water.

I was a little worried that the juniper would be overpowered by the pepper berries and on the nose, there is a melange of different aromas, a sweetness that gives way to spiciness but with fresh, herbal undertones. In the glass, the spirit is clear and a tad oily in the mouth with the spiciness and dryness of the pepper berries aided and abetted by the juniper – yes, it is there, but struggling for attention – smoothed by the citric elements before the herbal elements move in to give a refreshing and lengthy aftertaste. The gin met its brief in giving a particular Tasmanian twist to the London Dry style and while it made for a pleasant enough tipple, I would have preferred a bit more juniper. Chacun à son goût, of course.

Until the next time, cheers!

July 26, 2023

The Secret Search

A review of The Secret Search by E R Punshon – 230706

Here’s a mystery before we start. The cover of the reissued edition of this book by the excellent Dean Street Press shows it to be the twenty-eighth in Punshon’s Bobby Owen series while the usually reliable Fantastic Fiction shows it as the twenty-ninth, appearing after The Golden Dagger, both of which were originally published in 1951. It matters not a jot for the appreciation of the book, only a confusion that is a tad irksome for those who like to read a series in chronological order.

There is a much grittier, darker side to Punshon’s post-Second World War stories, and The Secret Search follows this trend, as we find ourselves hurled into a feud between two gangs, one led by Cy King whose air of invincibility had been punctured by Owen’s sleuthing previously and the other by Tidy Garden. The denouement, which is the highlight of the book, results in the inevitable violent conclusion to the rivalry, justice of a sort being done, and a happy ending for at least two of the leading characters.

I found it one of Punshon’s least successful novels, mainly because there was nothing tangible for the sleuth to get his teeth into. It was all suspicions that things were not right, that circumstances were leading up to a crime being committed, possibly even murder, and even when Commander Owen of the Yard’s acute nose for trouble proves spot on, there is nary a piece of evidence that would stand up to the forensic scrutiny of a defence barrister. At one point we even venture into the world of Extra Sensory Perception and codes, the relevance and importance of Me OK is never really satisfactorily explained. The secret search of the title is the hunt for a person, whose disappearance is reported by Ted Wyllie whose motives and role in the plot only become clear at the end.

It is also a tale of impersonation. Owen is indignant that one of Cy King’s gang impersonates himself in order to gain access to premises and case the joint, as they say. The plot revolves around the impersonation of Elizabeth, the niece of a rich old man, Mr Smith, and the real niece’s disappearance. At one point in the story there are three Elizabeth Smiths involved. And is it fanciful to think that Bobby Owen saw his young self in the form of a lowly police constable, Fred Ford, whose initiative caught his attention and whom he transferred to CID pronto?

While the plot seems complicated it boils down to a plan by the gangsters to get hold of an old man’s estate worth around £200,000 by introducing him to his (fake) long-lost niece just returned from Canada in the hope that he will leave his money to her and, of course, accelerating his demise. He is found dead in his bathtub. Whether any hardened gangster would have thought that the turn of events needed to make the plot come to fruition was worth the hassle is doubtful, especially as the arrival of the real niece, as happens, could easily scupper the plans. Olive, the ever-faithful housewife and font of sage advice, makes more of an appearance in this one and I always enjoy her contributions and her marked exasperation at her husband’s failure to see the wood for the trees.

It was interesting to see Punshon took inspiration from a passage from Xenophon’s Anabasis for the psychotic drug that kept the real niece quiet, mad honey made from honey collected from the summer blooming Datura which is commonly found in the hedgerows near Blogger Towers. Despite the odd point of interest, though, the book did not grab me as Punshon’s normally do and its pace, funereal at times, almost came to a halt at the midpoint. Whether it is number twenty-eight or 29, I am happy to move on to number thirty.

July 25, 2023

Suddenly At His Residence

A review of Suddenly at his Residence by Christianna Brand – 230702

It was once said that if you borrowed a crime fiction novel from a public library, always check that the last page is intact or else you run the risk of missing out whodunit. In truth, very few, if any, of the novels from the Golden Age of detective fiction have left it to the last page but in this novel by Christianna Brand, the third in her Inspector Cockrill series, originally published in 1946 and now reissued as part of the excellent British Library Crime Classics series, it is the very last sentence of the book that the solution to two impossible crimes is revealed. I will not put my foot in it by saying much more, but if you are reading a physical copy make sure that the vital final page is there.

On the face of it, the book, which goes by the alternative title of The Crooked Wreath, is a rather conventional story featuring a country house, a curmudgeonly, cantankerous head of the family, Sir Richard March, who rather mawkishly puts his first wife, Serafina, on a pedestal and marks the anniversary of her death with rituals that the rest of the family have to join in with, the rather foolish announcement that he is going to change his will, disinheriting his grandchildren, and settling all on his current wife, Belle, and the inevitable demise of Sir Richard, poisoned, and the disappearance of the new will.

However, unsurprising as these events are, Brand decides to spice things up by turning March’s death into an impossible murder. He had gone off in high dudgeon to change his will, amusingly getting members of the family to give him the instruments he needed to disinherit them, a pen and access to a lawyer, to stay the night in the cottage in which Serafina had died. Unlike most impossible murders it does not involve locked rooms but rather rose bushes, the roses being at just that stage where the slightest brush against them will knock them to the ground, and paths which had been freshly sanded and would show any footprints. Nevertheless, someone had managed to poison the old man.

But not content with one impossible murder Brand throws in a second, the poisoning of the old gardener who knew a little more about the family than they gave him credit for and was not above exploiting it for his own gain. Again, footprints, or rather the absence of them, give his death the air of impossibility as he is surrounded by a sea of dust with only his footprints visible. There is a suicide note in which he confesses to Sir Richard’s murder but it always dangerous to assume a degree of literacy amongst the lower orders.

There are only six possible suspects, one of whom could be eliminated from the second murder, and by logic from the first after they had been arrested following a grave miscarriage of justice at the coroner’s hearing. Their crime was to be a foreigner, an outsider who was only a member of the family through marriage. Edward is the most interesting of the family members, a man whose exposure to alienists, the then term for psychiatrists, has convinced him that he is prone to “fugues” and can lose control of his actions without remembering what he has done, the perfect fall guy, in fact. His fragile psychological make-up is rather cruelly, in modern eyes, played upon.

As it is 1944 and the war is still on, a flying bomb appears deus ex machina to bring matters to a head and allows Cockrill, whose low-key approach to sleuthing primarily involves getting the suspects to talk amongst themselves and see what transpires, to play the role of God by deciding which of the two trapped in the resulting inferno should be rescued, the murderer or the innocent.

There are plenty of twists and turns and competing theories as to who and how the murders were done. The purist would argue that there are more holes in the plot than in a colander and while that is true and there is an element of impossibility to the explanation of the way both impossible murders were committed, Brand manages to divert the reader’s attention with a tour de force of some not inconsiderable brio and humour. It is well worth a read so that you can judge which side of the fence you sit on.

July 24, 2023

Another Glimpse Of A Rainbow

To see a rainbow, the viewer must have the sun behind them at an elevation of less than forty-two degrees, the point at which shadow’s length becomes greater than their height. There must be water droplets in front of them, usually in the form of a passing rain shower, falling in the direction of 42 degrees from their shadow. If the sun’s elevation is greater than forty-two degrees, the rainbow is out of sight below the horizon. The lower the sun’s elevation, the taller the rainbow.

Intriguingly, a rainbow is little more than an optical illusion; it does not exist in a specific spot in the sky. What this means is that even if two people standing side by side see a rainbow in the sky, it is unique to each observer. It also raises the deep philosophical question of whether a rainbow really exists without the presence of a sentient being to recognise it for what it is.

Is there is a pot of gold buried at the end of the arc? The origins of this enduring myth lie in an Irish folktale about the Viking’s invasion of their island. Looting and plundering at will, they buried their spoils all around the countryside. In their haste to leave, they left some of their treasure behind, which the leprechauns found. Being distrustful of humans, the leprechauns took the gold and buried it deep underground around the island, the only clue to its whereabouts being the end of a rainbow.

Anyone hoping to get rich quick by unearthing a pot of gold will be sorely disappointed. As raindrops are spherical, when sunlight passes through them at just the right angle, they form a circular rainbow. The reason that only a part of a rainbow, the arc, is usually visible is that the Earth’s surface blocks out the rest of the light. A rainbow in its full circular glory can occasionally be seen from the top of a mountain or the cockpit of an aeroplane.

Looking out of an aeroplane window, a passenger might see what looks like a circular rainbow around the shadow of their head, made up of one or more successively dimmer concentric circles, each of which has red on the outside and blue on the inside. Like a rainbow it is an optical illusion, known as a glory, but is the result of a completely different physical process, the wave interference of light, usually from the sun but also the moon, internally refracted within small droplets.

Occasionally a second rainbow appears in the sky slightly above the primary rainbow. It develops when light entering a raindrop undergoes two reflections instead of one and is scattered at an angle of fifty-one degrees. The second reflection not only reduces the intensity of the light but also reverses the order of the colours, with blue at the top and red at the bottom.

A tertiary rainbow occurs when light is reflected for a third time. The these can only be seen by looking directly towards the sun, because the sun rather than the point directly opposite (the antisolar point) is its centre. This makes it difficult to spot, especially as the intensity of the colours is much reduced, and the bands are broader.

A quaternary rainbow, where the light is reflected four times, is fainter still and can only be observed while looking at the sun. Under laboratory conditions, scientists had detected a 200th-order rainbow, where the light has been reflected two hundred times.

Whether you are of a scientific or romantic disposition, there is much to marvel about a rainbow. As William Wordsworth observed; “my heart leaps up when I behold/ a rainbow in the sky…”

July 23, 2023

Lost Word Of The Day (54)

One of the most astonishing careers was that of Peter Brough who managed to build a career on the radio culminating in the early 1950s hit show, Educating Archie. He was an Engastrimyth, the favoured word for those who prefer to derive from Greek rather than Latin for a ventriloquist. Quite why he was so successful in a medium which relied on sound only is a mystery, but fair play to him.

Engastrimyth and ventriloquist are their exact equivalents in their respective languages, en in Greek meaning in, gaster belly, and muthos speech, while in Latin venter means stomach and loqui to speak. Curiously, ventriloquism contains every letter of the alphabet from Q to V including two of the least commonly used letters, q and v.

Propinquities and quadruplications each use the same run of eight letters (NOPQRSTU), unsurpassed in the English language unless you brazen-facedly allow the alphabet to loop round, in which case brazen-facedly featuring YZABCDEF would qualify.

July 22, 2023

Lost Word Of The Day (53)

I am able to recognise faces well enough but have a shocking memory for names. It might take me several minutes before I can recall their name but, fortunately, it is always possible to have a conversation with someone without having to mention their first name.

The Scots have a word for it, tartle, which refers to that awkward moment when you are introduced to someone whose name you cannot recall. If you feel the need to address them by their name but cannot dredge from the recesses of your memory, you could always say “Pardon my tartle”. That will break the ice if nothing does.

More of an age thing, perhaps, but one that is increasingly afflicting me is onomatomania, the annoyance caused by the inability to come up with the right word at the right time. When my mind goes blank, perhaps I should say “Pardon my onomatomania”.

July 21, 2023

Crime At Guildford

A review of Crime at Guildford by Freeman Wills Crofts – 230701

One of the reassuring things about picking up a novel by Freeman Wills Crofts is that you know what you are going to get, a well-crafted puzzle and a detailed exposition of how Chief Inspector French, as he now is, wrestles with the problem and with a painstaking attention to detail with no corner unturned, he finally solves the case and gets his men. Crime at Guildford, originally published in 1935 and the thirteenth in Crofts’ Inspector French series, follows this template to a tee. Known as The Crime at Nornes in America it makes for a satisfying if not very exciting read.

There are two crimes for French to grapple with, although, technically, the murder of Minter, the accountant of Nornes Ltd, a renowned London jeweller, who is found dead in his bed at the home of the company’s managing director just outside Guildford is the responsibility of the local police. The theft of half a million pounds worth of jewels from the company’s safe in the heart of London is French’s primary focus but as the two crimes seem to be linked, the Yard and the Guildford police, under French’s guidance, join forces to crack the cases.

Nornes is in financial difficulties and the board of directors are debating whether to declare the company bankrupt which will wipe out the shareholders or to raise more capital in the hope that trading conditions, which have deteriorated following the Depression, will turn round enabling them to weather the storm. The key directors are split as to what to do and hold a meeting at Norne’s Guildford residence over a weekend to decide upon the best strategy to resolve the company’s predicament. The jewels, valued at about £34 million in today’s terms, are the company’s principal assets and their loss is a major blow.

Crofts is at his best in coming up with ingenious solutions for seemingly impossible and perplexing problems. There are two keys to the safe in the firm’s Kingsway offices, one held by Norne and the other by Minter. They are different and the two must be used in tandem for the safe to open. Neither left their possession and French’s meticulous enquiries into the movements of all the key characters demonstrates to his satisfaction that the two had not collaborated to open the safe. Nonetheless, it seems to be an inside job, one achieved by taking photographic images of the original keys and then cutting another set from them. It is a highly original solution, although whether it would have worked in practice, I am not sure.

The other stroke of ingenuity is the way that Minter’s body was placed into the bed at Norne’s Guildford residence, a process involving hoists and ropes. Once French has realised how both these elements have been achieved, he is certain he knows the identity of the murderer and the jewel thieves. Catching them and having enough evidence to secure a conviction is another matter but as the case nears its conclusion, the pace of the book rises above its glacial progress. There is a chase over to the continent and the thieves are caught with the jewels in their possession. With the jewels restored and the culprits caught, French’s reputation in the Yard soars even higher.

There is one curious aspect to the structure of the book. We learn about the financial travails of Norne’s through the eyes of Sir Ralph Osenden, one of the key non-executive directors, and then he almost disappears completely from the narrative. Whether Crofts intended the reader to think that he would emerge as the eminence grise as the solution unfolds is unclear, but it struck me as odd.

July 20, 2023

Noble Craft Brewing

On my blog I write a series called Art Critic of the Week which features examples of onlookers or caretakers mistaking exhibits of modern art for consumables. There was a spirit of this absurdist take on modern art when, with the curator’s permission, I hasten to add, I took away some of the bottles that were featured on artist, Rebecca Sarah’s, display at the recent and excellent A Stitch in Time exhibition at the Dye House in Shrewsbury’s Flax Mill. It was my introduction to Noble Craft Brewing, a small microbrewery based in Market Drayton.

Founded in 2020 the Brewery is the realization of the dreams of Wayne Leeke and Jack Hughes to establish a microbrewery dedicated to creating craft ales using the finest of ingredients. Covid restrictions and the desire to create a tip-top product meant that it was not until the following year that the first pint was poured for the paying public, at The Red Lion in Cheswardine. Their supply sold out within two days, an auspicious start from which they have not looked back.

They have currently seven ales on offer, four of which in bottles I sampled. The pick of the crop for me was Noble Blonde, light, with citrus elements, crisp and dry and with an ABV of 3.7% one that I could see myself whiling away a pleasant afternoon or evening in the company of. For the trainspotters, it makes good use of Goldings, Northern Brewer, and Challenger hops.

Noble Kingdom, with an ABV of 4.4%, is a very different take on a pale ale, slightly darker, drier, maltier, and fruitier with distinct overtones of pine and citrus. The hops used are Summit, Pacific Gem, and Palisade.

The third to be sampled was their Noble Pale, which was their original brew. At 4.4% but using Summer and Ernest hops, it is hoppy, slightly floral and very refreshing. It went down a treat as we sampled it in a garden enjoying the late afternoon sun.

Just to prove that Noble do not just produce variations on Pale Ales, I sampled Noble Scruffy Jon, their take on a dark ale, using Summit, Challenger, Fuggles, and Goldings hops. It was mildly fruity, almost stout like with a warming chocolate finish which at 4.5% would make for an ideal winter’s evening drink in an inglenook in front of a roaring fire. The name is taken from Jonathan Morris’s Scruffy Jon’s Encyclopaedia of Pub Life.

Noble have produced an interesting and tasty range of beers – I hope to sample their Crusade, Knight, and Wolf another time – and using a distinctive label design created by local artist, Rebecca Sarah, make quite a splash on the shelf. Definitely a microbrewery to keep an eye on.

July 19, 2023

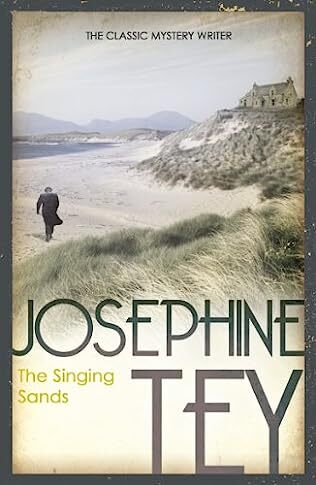

The Singing Sands

A review of The Singing Sands by Josephine Tey – 230627

Originally published in 1952, the year of her death, The Singing Sands is the sixth and final novel in Tey’s Inspector Alan Grant series. Grant is a much more complex, more human, more vulnerable character than the normal sleuth in the hands of other crime fiction writers. Indeed, in his final two cases, he is either in his sick bed looking for intellectual stimulation through the investigation of the mystery of the princes in the Tower in The Daughter of Time or, as is the case here, recuperating from what seems to be close to a nervous breakdown brought on by overwork and characterised by extreme bouts of claustrophobia.

The Singing Sands is a book about mania, obsession, and battles with demons. Grant is travelling up to the Highlands of Scotland to stay with his cousin, Laura, and her husband, Tommy, one of Grant’s old school friends, and to spend some weeks engaging in an activity which he regards as being somewhere between a sport and an obsession, fishing. He hopes that the open spaces, the fresh air and the exercise will help him recover his equilibrium and help overcome his almost debilitating fear of confinement in close spaces.

However, as is often the way with detectives on leave, his trip to Scotland turns out to be something of a busman’s holiday. As he leaves the sleeper, he sees the ticket inspector trying to rouse a passenger in a compartment reeking of whisky, a vain task as the man is clearly dead. Grant, unlike the usual ‘tec, walks away but in the restaurant finds that he has picked up the dead man’s newspaper in which is inscribed a set of enigmatic lines including the one from which the book draws its title. Grant is intrigued and wonders what the lines mean and what the young dead man was up to. Was he too a troubled soul, battling his demons, finding his route to salvation not in the form of a fisherman’s fly but in a bottle?

Rather like a fish he was hoping to catch, Grant swallows the bait hook, line, and sinker and spends much of his time trying to identify the man, discover the reason for his death – he doubted it was a simple case of suicide – and, if necessary, bring the dead man justice. Some of us read books or do crossword puzzles for intellectual stimulus in our leisure time but detectives just solve cases.

Inevitably, there is a complex story behind the young man’s demise and while there is a Singing Sands in the Western Isles which Grant identifies and visits, the sands which are mentioned in the verses are to be found in Arabia and hide a lost city, a veritable Shangri-La, revealed as the young man, a commercial pilot, flies through a dust storm. It turns out to be a tale of obsession and greed, more forms of mania, in which overarching ambition leads men to commit crimes to frustrate the plans of others. The book’s resolution relies upon a death bed style confession in the form of a letter which I always find a tad unsatisfactory.

However, although there is enough in the plot to keep the reader on their toes, Tey’s books are more than a piece of routine crime fiction. She is more of a novelist, as much if not more interested in the psychology of her characters and their reactions to the situations in which they find themselves as resolving a complex chain of events. Her writing style is beautiful, her love for the country and her appreciation of the wonders of nature profound. It is a delight to read.

The story also shows a delicious mix of the modern and the old. Grant travels sometimes by aeroplane, a challenge for someone with severe claustrophobia which he manages to overcome, and yet relies on the time-tested method of inserting advertisements in the national papers to give him a lead. One advert in a roundabout way brings a young American pilot into the story and it is his inside knowledge of the victim that helps Grant move nearer to finding out what happened to him. There Is also much about the Scottish independence movement, and wry observations about those who have loose associations with the country adopting all its supposed customs and costumes with gusto.

Grant returns to work, his Scottish jaunt having proven to be the tonic he needed, even though he had considered resigning and turning to pastures new. The irony, of course, that this book, published posthumously, marked the end of his career due to Tey’s untimely death at the age of fifty-six.