Martin Fone's Blog, page 53

May 4, 2024

Nelson The Clown

There always used to be a frisson of excitement when the circus came to town and the arrival of William Cooke’s Royal Circus at Great Yarmouth on May 2, 1845, was no exception. To promote the attractions of the troupe, a spectacular opening event was planned, which involved Nelson the Clown, described on handbills as a “low comedian”, floating down the rivers linking one end of the town to the other, pulled by four swans.

Such was the novelty of Nelson’s performance that thousands lined the river banks with some four hundred standing on the Yarmouth suspension bridge. Beginning his journey at Haven Bridge at Hall Quay on the flood tide, the unusual procession made its way to the Suspension Bridge at North Quay, Nelson responding to the cheers of the crowd by waving and the swans even honking in appreciation. As he neared his final leg of the journey, passing under the suspension bridge, part of the crowd on the bridge pressed forward to get a better view.

Then disaster struck. One of the rods gave way and chains on one side of the bridge snapped, tipping the bridge over and catapulting those on it into the river. Frantic rescue efforts began, every available medical person was summoned to the site, and the injured were treated in Vauxhall Gardens on the west side of the Bure and in houses along the east bank. However, it soon became apparent that a major tragedy had occurred.

One by one bodies of victims were pulled out of the river, who had either drowned or been crushed by falling bodies and sections of the collapsing bridge. The bodies, seventy-nine in all, were laid out at the Norwich Arms Inn, the Admiral Collingwood and Swan public houses, the youngest victims, Mary Ann Lake and Charles Dye, just two years old and the oldest, Mary Ann Ditcham, 64. Fifty-eight of the dead were aged sixteen or under.

Every part of the town was touched by an event that had triggered the largest recorded loss of life in Great Yarmouth. The Norwich Mercury described the aftermath to its readers on May 10, 1845 thus; “In every street are to be seen one or more bodies extended on biers, returning to that home from which but short minutes before they had passed in health and life. The consternation – the agony of the town is not to be described – it is as if some dread punishment was felt to have fallen upon its inhabitants – every face is horror stricken – every eye is dim”.

Following a local campaign a memorial was installed in 2013 to commemorate the tragedy. It took the form of a stone book bearing three images, that of a young family, of Nelson with his four geese and a list of all the victims together with their ages. As for Nelson, he continued performing the same stunt for years. That’s entertainment.

May 3, 2024

The Essex Murders

A review of The Essex Murders by Vernon Loder – 240328

After reading some of John Vahey’s books under his nom de plume of Henrietta Clandon, I decided to sample some of his novels written under his more familiar pseudonym, Vernon Loder. The Essex Murders, known by the alternative title of The Death Pool, was originally published in 1930 and is the first, albeit of only two, in his Inspector Brews series.

The Inspector is a likeable, empathetic investigator with a smile on his face, one who is, if not happy, prepared to put up with the involvement of a couple of amateur sleuths whom, to his credit, he acknowledges as giving him the clue that eventually leads to the resolution of a crime committed in the soggy fenlands of Essex. One of the amateurs, Ned Hope, has more than a little skin in the game as he has just purchased, using up all his financial resources, the dilapidated Fen Court, set in the middle of nowhere, only to find, to his horror, that three bodies have been fished out of one of the four ponds at the bottom of his garden. His fiancée, Nancy Johnson, provides the unobtrusive love interest and keeps Ned, prone to flights of fancy, firmly on terra firma.

The victims are a wealthy man by the name of Habershon and his wards, two cousins who plan to get married against his wishes. The two youngsters have their wrists tied to each other and there is a fragment of a note pinned to the girl’s clothing suggesting their intention to commit suicide. The initial working theory is that they did away with themselves and that Habershon rushing to the scene too late to prevent the tragedy, slipped, hit his head and drowned in the pool. The watches of the dead men stopped within four minutes of each other.

However, as the case is investigated, it is clear that the facts, not least the position of Habershon’s abandoned car, do not support the suicide theory, but if it is murder, was Habershon the culprit but had an accident before he could leave the scene or was someone else responsible for a triple murder and how was it accomplished?

Among the pertinent clues that emerge are a thermos containing Brazilian coffee laced with a sedative, a punt that was taken without permission, marks on the river bank, and the curious behaviour of Cornelius Hench, Ned’s nearest neighbour, who claims to be something of an ornithological expert but who confuses a kestrel for a hen-harrier. Hench has an almost too perfect alibi and does not seem physically strong enough to have hauled the bodies from the punt into the pond.

The interaction between Ned and Brews is one of the highlights of the book. Whenever Ned seems to have made some headway in his investigations, he finds that Brews with his annoying routine is normally one step ahead of him. However, his observations about the lights of the abandoned car being on which must have made it observable at the time of the murders and throws doubt on the account of one of the characters enables Brews to make sense of what happened.

With very few characters in the story, let alone credible suspects, Loder does a fine job in maintaining the tension and spinning out the resolution of the mystery, but simply because of the paucity of characters he has to pull off an astonishing piece of legerdemain to bring in two more suspects in at the death. Armchair sleuths might throw their book down in disgust that the author has not played fair, and indeed he has not, and the plot does suddenly veer to one of the appropriation of bearer bonds and the opportunity for a couple, not previously thought to have any relation with each other, to make money beyond their wildest dreams and a fresh start. It does challenge the preconception that just because someone is an x – insert profession or rank as appropriate – they cannot have committed murder.

The pace of the ending, in which both Ned and Brews manage to have their heads bashed in, makes up for the rather slow, ponderous start. Once the book gets going it is an entertaining read with some fascinating characters and a plot that never lull the reader into complacency. For Ned, at least the murders are the making of him financially and bring him a wife.

The moral of the story is never develop lumbago out of the blue.

May 2, 2024

Three Magnets

By the last decade of the 19th century around 80% of the population of England was living in urban settings, lured from the countryside by the prospect of finding streets paved with gold only to find that they were living in crowded and insanitary conditions. Some enlightened thinkers began to consider how the dreadful conditions could be improved. One such was parliamentary stenographer, Ebenezer Howard, who thought the answer was to combine the best of the town with the best of the country.

“Human society”, he wrote in Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform (1898), “and the beauty of nature are meant to be enjoyed together…Town and Country must be married, and out of this joyous union will spring a new hope, a new life, a new civilisation”. Not content with pious platitudes, Howard formed the Garden City Association in 1899 with the intention of promoting social justice, economic efficiency, beautification, health, and well-being in an urban setting.

Most dramatically, he summarised his vision of a garden city, encapsulating the best of both words, in a diagram which appeared as a frontispiece to his Garden Cities of Tomorrow (1902). It featured three magnets: the first two magnets represented the advantages and disadvantages of urban and country life while a third combined the advantages of both to provide a panacea for urban planning.

His vision foresaw strong community engagement, community ownership of land, mixed-tenure homes that were genuinely affordable, a wide range of local jobs within easy commuting distance of homes, well-designed homes with gardens, green infrastructure, cultural, recreational, and shopping facilities, and integrated and accessible transport. Each town would be limited to 32,000 residents, be self-sufficient as far as possible, and have a circular design.

The first manifestation of Howard’s design concept was Letchworth, the world’s first garden city, construction of which began in 1903. Howard had to raise the monies necessary from “gentlemen of responsible position and undoubted probity and honour” who would collect interest on their investment if the garden city made profits through rents, a move which inevitably meant that he had to compromise on his principles, including the elimination of the co-operative ownership scheme and employing architects who did not agree with his rigid design plans.

Nevertheless, with just twelve houses to an acre, clearly defined building standards, tree-lined roads, generous open spaces, and factories, such as the Spirella factory, light and airy with two glazed workshop wings, much of Howard’s vision came to fruition. One of the architects, Barry Parker, even lived in a semi-detached house on Letchworth Lane from 1906 to 1935.

The garden city concept as epitomised by Letchworth gained worldwide acclaim. Frustrated, though, by government’s unwillingness to adopt his design principles, Howard raised enough money in 1919 to buy land at auction in Welwyn. The Welwyn Garden City Corporation was formed to oversee the construction, but although it is the UK’s second garden city its proximity to London, just twenty miles away, meant that it was never self-sufficient.

There might be only two garden cities in England, but Howard’s three magnets emphasised the need for urban planning policies that eventually led to the New Town movement.

May 1, 2024

My Bones Will Keep

A review of My Bones Will Keep by Gladys Mitchell – 240326

Opening a Gladys Mitchell book for the first time, I take a deep breath just like I would if I was going to plunge into the loch that surrounds Tannasgan on which stands An Tigh Mór. It is going to be a shock, but will be exhilarating and might even be pleasurable. My Bones will Keep, the thirty-fifth in her Mrs Bradley series, originally published in 1962, is no exception. Her harshest critics will argue that she does her best to bewilder and confound her reader, immersing them in a world that is weird, eccentric and not a little made but one with more than a little perseverance sort of makes sense.

It is tempting to say that all the reader needs to do is read the final chapter in which Detective Inspector Gavin, who has been working, unbeknownst to Mrs Bradley, now Dame Beatrice, and her secretary and Gavin’s wife, Laura, on one aspect of the case, pulls all the pieces together of a puzzle which involves “a loch, an island, treasure, two corpses, and a couple of madmen” to bring some sense and order to the case.

One of the highlights of the book is Mitchell’s description of the Scottish scenery, whether it be Edinburgh itself or the remote Highland countryside in which much of the book is set. Rather like E C R Lorac she exhibits a wonderful sense of place and displays a love of the rugged scenery and the quaint rhythms of Highland life. But she is not averse to telling the Scots a few home truths. Gavin calls the Scots, of whom he is one, “a prejudiced, sentimental, insular, irrational people”, citing as his evidence the kilt, the sporran, the Gaelic language, the Highland weather, Robert Burns, tossing the caber, deerstalking, and Bannockburn. It sounds like the lyrics of a Scottish Ian Dury.

The book starts off conventionally enough with Dame Beatrice attending and delivering a paper at a conference in Edinburgh. Laura, her high-energy secretary, is at accompanying her and, as her husband is off on a trip allegedly catching barracuda but possibly fish of a redder hue, she is given time off to explore the Highlands, and particularly to visit the gardens of a Mrs Stewart, a friend of Dame Beatrice. Even before she has left Auld Reekie, she witnesses a murder when two men seem to push another in front of a vehicle.

Out in the wilds of the Highlands, she meets a couple, the Grants, whose car has broken down and, at the husband’s request, Laura drives Mrs Grant back to her house, where she spends the night. The following morning Laura is disconcerted to find that her car had been used and she had been overcompensated with petrol. Seeking refuge from a rainstorm she is persuaded to go to Tannasgan where she meets an eccentric red-haired red-bearded man and disturbed by the atmosphere escapes, aided by a man lurking in a boat shed. While they are making their escape the hear the swirl of pipes which suddenly stop. Later, they learn that the laird, Cu Dubh, has been murdered. Wherever she goes, Laura then seems to encounter the same people.

Back in Edinburgh, this is a mystery too intriguing for Dame Beatrice to resist. Mitchell does her best to confound her reader introducing too many characters with the same surname and several with changing identities. There is rum smuggling and gun running, suspicious comings and goings, but what the story boils down to is revenge, giving another the opportunity to run off with the treasure stashed in the cellar of the old house. Justice of a sort is done as the miscreants either skip the country, kill themselves or there is neither the will nor evidence to prosecute.

Mitchell gives her story an air of authenticity with her heavy use of Gaelic and the translation of Crioch is heady with meaning. Reading the book is like jumping on to a carousel which spins more and more out of control, leaving you dizzy without getting anywhere. It is accessible enough but it is hard to escape the conclusion that it is much ado about not very much.

April 30, 2024

Winning Strategies For Games Of Chance

In an Olympic year it might be churlish to gainsay the founder of the modern games, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, whose mantra was that “the most important thing in the Olympic Games is not winning but taking part; the essential thing in life is not conquering but fighting well”. That is all very well, but for some psychologists and game theorists rock, paper, scissors (RPS) offered the opportunity to develop strategies that reduced the impact of the implied randomness of the game.

A fascinating article published in Physics and Society in April 2014 by some researchers from Chinese universities described the cognitive processes involved in the game. Taking 360 students and breaking them down into groups of six, they asked them to play 300 games in random pairings allowing them to observe how the players rotated through the possible options. To incentivise them, the players received a small cash prize each time they won.

While there was a slight bias in favour of rock and scissors (35 per cent each) compared with paper, players selected their options randomly on average. However, there was a distinct pattern to the way players behaved after the result of a round of RPS. Those who had won were more likely to stick with their selection, whereas those who had lost not only were prone to change their choice but also to follow a clear sequence, choosing paper after rock, scissors after paper, and rock after scissors and so on.

An understanding of this process, which the researchers called a “win-stay lose-shift strategy”, opens the way to developing a winning strategy. The key is to be a reactive rather than a random or reflexive player, concentrating on reacting to how your opponent plays. As most winners stick to their choice and losers alter their choice in a cyclical fashion, this can be turned to advantage.

The researchers do sound a note of caution, though, by pointing out that opponents who also adopt a reactive strategy will be more difficult to beat. However, they observe that facing an opponent who is confident enough to break away from the “win-stay lose-shift strategy” is rare and basing a strategy on the assumption that most players will stick to a reflex-based strategy will, on average, improve the chances of winning. Extending the concept, Neil Farber, writing in Psychology Today in April 2015, provided a handy list of nine strategies to adopt against non-random players of RPS.

Weighty matters have been decided by a game of RPS. In 2006 a Federal Judge in Florida, Gregory Presnell, ordered the two sides in a lengthy case to settle the matter with a game while three police officers were reprimanded in 2015 for allowing a underage drinker to avoid a fine after beating them at RPS. Even august auction houses, Christie’s and Sotheby’s, resorted to playing a game, under their client’s instructions, in 2005 to determine who would have the rights to auction a collection of impressionist paintings. Taking advice from the 11-year-old twins of a director to choose scissors, Christie’s won, earning a sizeable commission from the subsequent auction.

In the days of yore when our rivers were not full of effluvia, a game of Poohsticks was a pleasant way to spend a summer’s afternoon. It is simple enough, competitors dropping sticks off a bridge into a river upstream with the winning stick the first to reach a designated spot downstream. To avoid unseemly arguments, perhaps to be settled by a game of RPS, each stick should be personalised in some way. AA Milne introduced the game, which he had played with his son off Posingford Bridge in the Ashdown Forest, to a wider public in his The House at Pooh Corner (1928), attributing its invention to Winnie the Pooh.

While 57% of Britons surveyed believe that Poohsticks is a game of pure luck, it too has fallen prey of game theorists. Dr Rhys Morgan of the Royal Academy of Engineering has developed a formula which enables a competitor to gain an edge, expressed as PP (a perfect poohstick) = A * E * Cd, where A is the cross-sectional area, I the density, and Cd is the drag coefficient. In layman’s terms the stick should be long and thick, heavy but not so heavy that it will sink, and with quite a lot of bark to catch the flow of the river like paddles.

Just 11% of the 2,000 respondents, the survey found, instinctively selected the right sort of stick while 30% went for a long, thin stick, which, according to Dr Morgan, is only half right. If you want to test his findings, head to one of these bridges, designated by VisitEngland, as the twelve best for Poohsticks.

Rely on your instincts or pay heed to the game theorists, the choice is yours!

April 29, 2024

The ABC Murders

A review of The ABC Murders by Agatha Christie – 240323

The thirteenth novel in Christie’s Hercule Poirot series, originally published in 1936, is generally regarded as being one of her best and it is so well known and has been so well analysed by critics and reviewers that it is difficult to find anything original about it. It does contain some unusual features which keep those he feel that she too easily slips into a tried and tested formula on their toes.

In format it starts out as an inverted murder mystery where the reader is given advance warning of who the killer is and we can smuggly watch the sleuths grapple their way through a morass of clues to reach the conclusion that we knew from the start. However, Christie knocks any smug complacency out of the park with a ferocious twist in the tale that upsets all preconceptions. Inspector Crome’s case against the prime suspect seems so convincing but there are a few little details that do not quite fit into the overall picture he has painted, enough to worry Poirot and set his little grey cells whirring.

There is more than a little humour in the book, perhaps more than I would normally expect from Christie’s pen. She enjoys through Poirot pointing out the differences in approach between her sleuth and Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, evidenced when Poirot pulls Hastings’ leg by plucking a description of the murderer out of the air from little or no evidence like the occupant of 221b Baker Street. She also references poetry, or at least a nursery rhyme, “and catch a fox/ and put him in a box/ and never let him go”, which gives a telling insight into the psychology of the culprit and alerts the reader that the inversion is going to be inverted.

Hastings makes a return, narrating the mystery, although he adds a few chapters here and there which are not from his journal but which, he hastens to assure us in the preface, he has verified with the best possible sources including Poirot. Always a man to state the bleedin’ obvious Hastings earns his spurs by making a banal observation that is so perceptive that it causes Poirot to reconsider his theories and come up with an alternative and radical solution to the problem at hand.

Unusually for Christie, she has a serial killer on her hands who seems to strike at random albeit with an overarching scheme. First Alice Ascher is murdered in Andover, Betty Barnard in Bexhill, and Sir Carmichael Clarke in Churton – you get the sequence. The murder leaves their calling card, a copy of the ABC Railway Guide placed under or by the victim, and each attack is preannounced by a letter addressed to Poirot himself issuing him with a challenge to apprehend the culprit if he can. The fourth murder, in Doncaster, seems to follow the same pattern but the victim is George Earlsfield.

There are aspects of the second murder that worry Poirot and he wonders why the letter announcing the third murder was misaddressed so that he and the police had no opportunity to prevent it. Indeed, why send the letter to him and not to the police or the press? Convinced that there is a causal link between the first three murders, Poirot pulls together a working party made up of relatives of the victims and through that discovers that a travelling salesman, selling stockings, had been in the vicinity of each murder at the relevant time.

However, Poirot cannot believe that the individual languishing in the police cells, having collapsed and given himself up in Andover, has either the intellectual capacity to challenge Poirot as an equal nor the personality needed to sweep a flighty young girl off her feet and arrange a nocturnal assignation on a beach. The true culprit, although superficially charming and eager to help, is a thoroughly nasty piece of work who has manipulated a psychologically damaged character to act as their fall guy. As is often the case, the plot is an enormously risky and unnecessarily complicated way of getting your hands on an inheritance.

The characters may be unrounded and the dialogue wooden, but you do not read Christie for a polished piece of literature as you would a Nicholas Blake, Gladys Mitchell or Josephine Tey. You pick up her books to be royally entertained, forget your cares for a few hours, and exclaim “did that really just happen?”. She achieves this in spades with The ABC Murders.

April 27, 2024

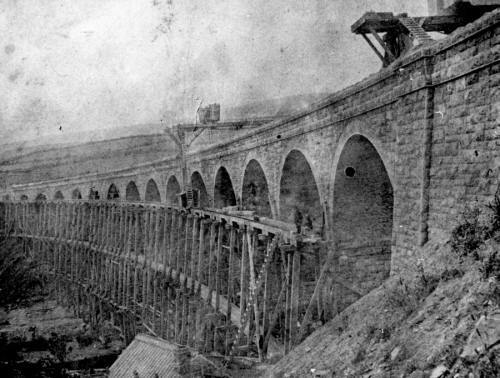

Cefn Coed Viaduct

The third largest in Wales, Cefn Coed Viaduct was built to carry the Brecon & Merthyr Railway over the River Taff near Merthyr Tydfil in South Wales. Designed by Alexander Sutherland and Henry Conybeare, it consists of fifteen arches, each one with a span of almost forty feet, and is 257 yards long with a maximum height of 115 feet. Described as a graceful and majestic structure, it has an impressive and elegant curve.

The designs were prepared by Alexander Sutherland and Thomas Savin and John Ward, managers of the railway company took responsibility for the build. However, they soon hit problems when the company, which had been paying a guaranteed five per cent dividend to shareholders, ran into financial problems. Sutherland stepped in to save the day, choosing an alternative route for the section.

The revised route avoided Cyfartha Castle, the property of local ironmaster, Robert Crawshay, by going down the west side of the valley, increasing the engineering complexity of the project but earning the gratitude of the influential landowner. It is alleged that a sizeable bribe eased the pain of the redesign.

A further problem hit the project when, in February 1866, stonemasons went on strike. The intention had been to build the viaduct out of limestone, like the nearby Pontsarn, which Savin, Ward, and Sutherland had also built. Instead, the company was forced to buy 800,000 bricks and employ bricklayers which is why bricks line the underneath of the arches while the rest of the structure is made of stone.

Eventually, on October 29, 1866, Mrs Sutherland was able to lay the final stone and the viaduct was declared open. It had cost £25,000 to build and was used until the line was closed to passengers in 1961 and the last goods train trundelled over it on August 1, 1966. It has since been renovated and now forms part of the Taff Trail walking and cycling route.

April 26, 2024

Eight To Nine

A review of Eight to Nine by R A J Walling – 240321

The curiously titled sixth novel in Robert Walling’s Philip Tolefree series, also known as The Bachelor Flat Mystery, originally published in 1934, is another story where the movements of suspects at a particular time hold the keys to the mystery. The hour in question is between eight and nine, when housekeeper Mrs Pilling is off duty at Elford Mansions, hence the title, and seasoned readers of the detective fiction genre will soon realise that the empirical evidence of time is not necessarily to be trusted.

The story also centres around a femme fatale, an actress by the name of Millicent Vane, a woman with a past and to whom several rich and eligible bachelors are attracted like bees to a honeypot. One such is Bill Chance, son of Lord Greenwood, and the worried nobleman engages Tolefree, insurance broker and amateur sleuth, to dig around and find if there is any scandal attached to the woman. Curiously, we never meet Miss vane. Despite his distaste for the task, Tolefree accepts the brief and accompanied by his faithful Watson, a ship broker by the name of Farrar, begins his investigations.

Acting on a hunch to visit rich playboy, Howard Klick, at Elworth mansions, Tolefree finds that the comedic Mrs Pilling has fainted and that there is a body of a murdered man in the flat occupied by North. Despite the assumption that the murdered man is North, Tolefree discovers, courtesy of a feather and an Australian penny, that the victim is Australian and that he is Pendleton, the husband of Miss Vane whom, when he was imprisoned for fraud down under, she left to come to England and seek her fame and fortune. Understandably, Pendleton was a bit miffed and when he was released sought his revenge.

The police investigation is led by Pierce and while he and Tolefree have perfectly amiable relations, they approach the case from radically different angles, coming up with two different culprits. Tolefree engages in a masterful piece of filibustering to prevent Pierce making a fol of himself and incurring the wrath of his fierce Scottish boss.

It is a tale of timetables and alibis with a reasonable number of red herrings and witnesses whose accounts are not entirely reliable. One credible suspect is summarily dismissed because he sailed from Australia to London in the Orlando second class and second and first class passengers never mix.

After much toing and froing, including a nighttime expedition to the wilds of the Fens, much to the discomfort of Farrar who had to tail a car at a speed above which he was comfortable driving at, Tolefree concludes that the culprit is someone who sailed on the Orlando at the time Miss Vane did, lives in Elford Mansions, maintained a flat for Miss Vane in Kilburn, and who had a rendezvous with Pendleton on the Thursday night in question.

These criteria together with the disappearance of the feather and Aussie penny from the scene of the crime seals the identity of the culprit. In Poirot style he lays out his findings before Lord Greenwood and an assembled group of suspects, demonstrating that Pendleton’s death was committed in self-defence rather than a premeditated act of murder.

It is a complex plot and the story is well told in an engaging style, Walling uses short burst of staccato-like sentences to inject some urgency into the narrative. I could not help thinking, though, that a chat with Miss Vane would have saved a lot of time.

April 25, 2024

Waterloo Station Clock

Where do you meet on a crowded railway concourse? The obvious place is under the station clock as it is usually centrally positioned so that it is visible from each of the exits from the platforms.

One of the most iconic meeting places is under the railway clock at Waterloo station, famously the meeting place for Laura and Alec in Noel Coward’s 1946 film Brief Encounter, although the scenes were shot at Carnforth station, and of Del Boy and his future wife, Raquel in the Only Fools and Horses Christmas special in 1988, Dates. Curiously, despite its iconic status, whenever I have arranged to meet someone there, there has been hardly anyone else staring anxiously and vacuously into the distance.

Manufactured by Gents of Leicester, on its installation it was described by the Daily Mirror in its edition of November 19, 1919 as a “two ton clock…of novel construction”. What was unusual about it was that it used within its mechanism an electric “synchronome”, which ensured that each of its four faces told the same time. It also had twenty-four hour faces, well before British Rail adopted the twenty-four hour clock as standard in 1964.

Waterloo’s clock was originally positioned in front of the taxi rank between platforms 11 and 12, platform 11 being the terminus for the Ocean Liner Expresses, and the Bournemouth Belle. When the Windsor train shed was demolished to make way for the International platforms, two new platforms, 12 and 13, were opened and the original platform 12 was redesignated 14.

It did not take long for the clock to be established as a meeting place. Londonist in their blog notes that in 1924 a short story syndicated in the press featured a meeting under the clock, another from 1927 spoke of an “under the clock” tradition for meeting at Waterloo a rendezvous that formed the basis for a romantic liaison in a 1935 short story.

Next time you are at the station, see just how many people are waiting under it. It might just lead to an exciting adventure!

April 24, 2024

Shroud Of Darkness

A review of Shroud of Darkness by E C R Lorac – 240318

The fortieth in Lorac’s long-running Robert Macdonald series, originally published in 1954, is as much a thriller as a murder mystery with a tale that involves the settling of scores that have lingered on from the Second World War. Sarah Dillon is travelling by train from Exeter to Paddington and is enjoying the company of a young man, Richard, who seems to become more distracted and agitated, especially when the train, whose progress is impeded by a thick pea-souper makes an unscheduled stop at Reading and two men, one a seemingly respectable middle-aged businessman and the other a bit of a thug, join them in the carriage.

To her surprise, Richard leaves the train abruptly as soon as it reaches its destination but is seriously injured in an attack. Who was Richard, why was he attacked, and by whom? At the same time there is an old case running, reopened for the third time, the discovery of what happened to an American, Darcourt, who disappeared in 1941. Inevitably, the two cases are intertwined.

Lorac has chosen her title well. The Shroud of Darkness not only describes the thick fogs that enveloped the country, especially London, in the early 1950s, making conditions ideal for miscreants to go about their work and especially difficult for those tasked with apprehending them, but also the fog that has descended over Richard’s mind, struggling to piece together what really happened on a traumatic night in 1941 when his life was transformed dramatically.

Shrouds, of course, lift and the book focuses on unravelling and explaining what happened that forced him to flee the Plymouth blitz with his clothes on fire and be taken up and adopted by a kindly but austere farming family in the wilds of Dartmoor. With her fine descriptive ability and her enhanced sense of place, Lorac brings the Plymouth blitz and the remote way of life on the Devon moors to life.

There are a couple of murders along the way but these are incidental to the plot, more red herrings and collateral damage than germane to the unmasking of Richard’s attacker and the unravelling of his backstory. Potential suspects come and go, a jealous brother-in-law, a gang who operate around the Reading area, Richard’s best friend, some unsavoury characters who hang out at the Whistling Pig, but it is pretty clear that there are only two realistic contenders and, frankly, while Lorac tries to cloud the reader’s assessment of one, the other was always the favourite.

That said, the whodunit is not really the focus of a book that shines a light on some of the murkier aspects of clandestine warfare and the role of sleepers and intelligence gatherers on the ground. We tend to think that this was the specialty of the Allies but the roundups of Germans and other nationals at the outset of the war shows that the concerns that German spies were operating in England undercover leading seemingly innocuous lives was very real. It is interesting to think that even in the mid-50s Lorac saw that as a subject upon which to build a story.

One fascinating feature of the book, at least to fans of Golden Age Detective Fiction, is the name checks that Lorac gives to her contemporary writers. On the train Sarah and Richard exchange books, she receiving a Josephine Tey for a Ngaio Marsh, getting the better end of the bargain. A homophone of the Tey title, The Franchise Affair, provides Macdonald with the final piece of the jigsaw.

Macdonald is an empathetic investigator with an approach that quickly wins the confidence of those he speaks to, but is not averse to overhearing conversations and a bit of action. The denouement played out on a ferry to Dunkirk makes for a dramatic ending to what is an impressive story and a welcome variation to the tried and tested murder mystery.