Martin Fone's Blog, page 131

February 24, 2022

Dancers In Mourning

A review of Dancers in Mourning by Margery Allingham

There is no getting away from the fact that in terms of style and literary quality Margery Allingham is a cut above many of her contemporaries who wrote detective fiction. This book, the seventh in her Albert Campion series and originally published in 1937 which also goes under the title of Who Killed Chloe?, has all the hallmarks of Allingham at her best, vivid writing, splendid characterisation, and an intriguing puzzle, but I must confess, I did find it hard going at times.

Perhaps part of my problem is that I did not really engage with the puzzle to begin with. A musical star, dancer Jimmy Sutane, is unsettled by a series of practical jokes which are played on him, the strangest being when a large party of the bigwigs of the County set arrived en masse at his country home, having apparently received an invitation to attend an afternoon soiree. There was barely enough china to go round. By this time Campion has been invited by Sutane to get to the bottom of these practical jokes.

Those impatient for a body have to wait some time until Chloe Pye, a dancer who has been recently hired by Sutane and who has invited herself down for the weekend, is seemingly run over by Sutane after she leant over a bridge and toppled over. Even the least astute of readers will realise that there is something fishy about the accident.

The police investigate and Campion is placed in somewhat of a dilemma. He has been engaged by Sutane and prima facie Sutane looks to be in the frame, especially as investigations unearth details of Chloe’s shady past and her previous involvements with the star dancer. Is he going to be instrumental in sending his friend to the gallows? To further complicate matters Campion has taken more than a shine for Sutane’s wife, a surprise for some readers who have followed the series who have always considered Albert to have a rather ambivalent attitude to the fairer sex.

Worse still Campion finds himself withholding evidence and providing misleading information. The situation becomes so intolerable that he decides to withdraw back to London and let events unfold for themselves. What rocks him out of his languor and brings him back into the action is a bomb blast at a quiet suburban in which Sutane’s understudy, amongst others, is killed. The investigations lead to the discovery of what we would now call an international terrorist connection, blackmail, and to a previous marriage.

Reluctantly drawn back into the fray Campion is convinced of the identity of the culprit which makes him even more uncomfortable about the situation he finds himself in. However, a song and his recollection of the circumstances of Pye’s death lead him to realise that he had misinterpreted the clues and that he had overlooked the real culprit. As events quickly unfold, we see that Campion, while providing much valuable assistance to the police, is capable of making a monumental mistake.

In this novel Campion is a much more vulnerable, more human individual, less certain of his intuitions and in his actions, an interesting other side to him. Allingham is fascinated to explore and describe her hero’s inner conflicts, which while making him a more rounded figure does slow the pace of the narrative down. It is as though she is fighting against the constraints of the genre.

One of the undoubted highlights of the book is the appearance of Magersfontein Lugg, Campion’s man, who is lent out to the Sutanes. His friendship with their young daughter provides some charming and comic moments, especially when he teaches her some of the tools of his former trade such as lock picking and the three-card trick.

An intriguing point is that a pub that features in the book is called the Spiked Lion, perhaps a reference to Brian Flynn’s book of the same name, published four years earlier.

There is much to admire about the book, but I do not think it is one of her best.

February 23, 2022

Dead Men’s Morris

A review of Dead Men’s Morris by Gladys Mitchell

Gladys Mitchell certainly did not spare the horses when she set about constructing the plot for this, her seventh novel in the Mrs Bradley series, originally published in 1936. It is an intriguing and complex tale where a little knowledge of Morris dancing, pig farming, heraldry, a dash of Shakespeare, and Oxfordshire folk lore would not come amiss. As I have now come to expect with Mitchell it is also slightly bonkers and written with great verve and humour.

Set in rural Oxfordshire, Mitchell has taken the unusual step of recording the dialogue of the rustic characters in a broad dialect. It takes a bit of getting used to and, frankly, adds nothing to the book other than accentuate the class difference between the toffs and their inferiors. Her characterisation is spot on, though, and I enjoyed her portrayal of the suitably named Pratt who seems to have fallen out of the pages of a P G Wodehouse novel. Mrs Ditch with her florid language and her troubles in controlling her wayward daughter, Linda, who provides the love interest, is also a wonderful character.

The saurian Mrs Bradley is also on top form and much more involved in the mechanics of the mystery than in other stories I have read. She goes out of her way to defend the police’s prime suspect, runs in her underwear across the fields to save her nephew, and on several occasions has to use her phenomenal, but normally dormant, skills to ward off attacks. It is also a story where her powers of perception and deduction and her knowledge of the human psyche come to the fore.

It is she who thinks that there is something suspicious about the death of an elderly solicitor, Fossder, who suffered a heart attack when he went off for a bet to see the Sandford ghost. There is then a second death, that of the unpleasant farmer, Simith, whose body is found on top of Shotover Hill, having been gored by a boar. Mrs Bradley realises that the old man had been transported up to the hill and then had a boar set upon him. Her piecing all the clues together prevents a third murder being committed during a Morris display.

Mrs Bradley’s stay with her nephew, Carey Lestrange, which began over the Christmas period, is certainly an action-packed one and her returns over the next six month continue to meet with excitement and danger. There is a relatively small cast list of suspects. Geraint Tombley, Simith’s nephew who had a tempestuous relationship with his relative, is the man in the frame, but there are others, as Mrs Bradley discovers a complex web of love interests and ambitions.

In truth, for such an elaborately constructed plot, it is a relatively straightforward mystery and the culprit is both easy to detect and identify early on, certainly by the standards of novels of this genre. The resolution is expertly handled, the reader led by the hand as they grapple to understand the complexity and meaning of the rather obstruse clues and the psychological makeups of the key clues, and provides Mitchell with the opportunity to handle the unmasking of the culprit in a light and amusing fashion.

What also stands out is Mitchell’s love and understanding of the countryside, its customs, and habits. The reader is treated to insights into the world of Morris, a form of dancing practised with much gusto by the villagers and the breeding of and habits of pigs and boars. But what makes the book even memorable is the quality of Mitchell’s writing and turn of phrase. Miss Bradley looking on ““with the maternal anxiety of a boa-constrictor which watches its young attempting to devour their first donkey” is a phrase that will live long in memory, even when the intricacies of the plot have long been forgotten.

February 22, 2022

The Chinese Shawl

A review of The Chinese Shawl by Patricia Wentworth

Never invite an amateur sleuth to stay with you. Murder seems to follow them around. If you are going to murder someone, make sure you are certain who they are. If you are going to wear a piece of someone else’s clothing, make sure that it is not distinctive. Those in a wrap are my takeaways from this, the fifth book in Patricia Wentworth’s Miss Silver series, originally published in 1943.

Even by the standards of the time, there is a certain cosiness and old-fashioned feel about this book, the ideal piece of comfort reading for a readership desperate to escape the rigours of warfare and the grind of daily life and rationing. Camberley’s finest, Patricia Wentworth, certainly knows how to write a story and keep her readers engaged and pulls out all the stops for her take on a country house murder. She draws her characters well, especially of Laura Fane, and it would not be a Wentworth without a little bit of love interest, Laura falling for the charms of a wounded war veteran. Apart from him, the only acknowledgement that there is a war going on is that there are a couple of evacuated families living in one of the Priory’s wings.

In truth, the story takes a while to get going, the set up complicated and requiring some careful explanation. Laura Fane was orphaned at an early age and was left The Priory, a country pile. Sadly, she did not have the funds to maintain it and so rented it to her aunt, Agnes. Now she has come of age, Laura is determined either to sell it or live in it. There is clearly a longstanding rift within the family and Laura’s relationships with her Aunt and Lucy Adams are distinctly frosty.

And then there is Agnes’ other niece, Tanis Lyle. She is a bit of a vamp, dangling men on strings, always on the look out to steal someone else’s boyfriend. With a string of jilted boyfriends, angry love rivals, and a shady maid, there are several people in the story who would jump at the chance of doing Tanis some mischief. Inevitably, Tanis is found dead, but who did it and why, and was she the intended victim? And what was the significance of a couple of threads from Laura’s missing Chinese shawl on Tanis’ hand?

As luck would have it, Miss Silver is a guest at The Priory and has been employed by Aunt Agnes to discover who has been responsible for some minor pilfering and then, when Tanis’ body is discovered, to discover who killed her. By an equally fortunate twist of fate, the police detective assigned to investigate the murder is Randall March, whose governess Miss Silver was. There is much playful dialogue between the two, an affection that you rarely see between sleuth and detective, the couple combining well to establish what has gone on. Miss Silver is content to sit innocently in the background, knitting away, plying her mind to the problem, playing on her role as a slightly eccentric house guest, while giving March some helpful steers.

There is only one murder to solve, a low body count by the genre’s standards, but the explanation of what happened is ingenious and well developed, even if the revelation of the culprit is more by way of confession than outright sleuthing.

I enjoyed what was an undemanding but entertaining read.

February 21, 2022

The First Ice Rink

The first to produce a solution to help skaters overcome the problem of unpredictable weather conditions was Henry Kirk of Tavistock Square who, on November 2, 1841, patented “a substitute for ice for skating and sliding purposes” which, he claimed, produced a smooth surface to ice, using alum, a chemical salt known for its high water content. The alum was crushed into a powder and melted in copper until a liquid formed. Sulphate of copper was added to introduce some colouring and then hog’s lard to make it slippery. Once it had cooled, it was made into slabs, ready to be laid down to make “an extended continuous even surface, which may be a horizontal surface, an inclined surface, or a curved surface”.

Kirk first demonstrated his invention by constructing a rink measuring 12 feet by six in a seed room in the grounds of a nursery near Dorset Square, partly to attract investors. A second demonstration followed in July 1842, when “a sheet of ice” was laid down at the “Colosseum” in Regent’s Park. According to the Times, “the most expert skaters may be daily seen practicing” there. Providing a summer venue for skaters made Kirk’s point and he was able to raise the capital for a more extravagant enterprise.

In 1844 Kirk opened the Glaciarium, a rink with “a surface of 3,000 feet” made to resemble the Lake of Lucerne, an expanse of ice embedded in painted Alpine scenery consisting of snow-covered mountains and precipitous glaciers. Mounds of “snow” were piled around the edge of the rink. Littell’s Living Age claimed that “the judicious management of the light [gave] everything a cold and wintry appearance”. There was even a resident “promenade band” to serenade the skaters, led by Mr A Sedgwick.

Amongst is visitors were Prince Albert and Prince Alexander of the Netherlands, although there is no evidence that they took to the ice. The Glaciarium opened its doors at the Baker Street Bazaar in Portman Square, rather incongruously as an attraction to a cattle show, but by May 8th had moved to Grafton Street East, just off Tottenham Court Road. Admission cost a shilling, with a further shilling payable to skate on the rink.

Within four months the novelty of Kirk’s enterprise had worn off, the Glaciarium shutting its doors for good, the unremitting stench from the lard from the fifty hogs used to create the surface proving too much even for the most enthusiastic of skaters. Another three decades would elapse before another artificial rink was produced, the impetus to provide a solution prompted by a tragic accident.

An exceptionally cold spell of weather in January 1867 froze stretches of open water including the boating lake at London’s Regent’s Park, making them an irresistible attraction for would-be skaters. On January 14th the ice gave way, plunging twenty-one skaters into the water. All were rescued alive. Overnight the water refroze at Regent’s Park, prompting more skaters to take to the ice. At around 3.30pm the ice cracked again, and over two hundred of the revellers found themselves in the water. Impeded by heavy clothing and many unable to swim, forty perished, either from drowning or from hypothermia. The lake, which was twelve feet deep at the time, was made shallower to prevent such a tragedy recurring.

Ice rink technology’s next advance was a byproduct of John Gamgee’s attempts to freeze meat for importing from Australia. He developed, and patented in 1870, a method for making artificial ice, which involved running a network of oval copper pipes carrying a solution of glycerine, ether, nitrogen peroxide, and water, across a concrete surface with layers of earth, cow hair, and timber planks underneath. The pipes were covered with water and the solution pumped through, turning the water into ice.

To dip his toe into the water Gamgee demonstrated his rink in a small tent on January 7, 1876, before moving, in March, to permanent premises with a rink measuring 40 feet by 24 at 379, King’s Road. Operating as a members-only club, it followed Kirk’s template, decorated with Alpine scenes and with a gallery where spectators could view “several noblemen and gentlemen…skating with expressed satisfaction”. Gamgee also called it a Glaciarium.

Emboldened he opened a second Glaciarium, on a barge moored off Charing Cross, with a rink measuring 115 feet by 25, and one in Rusholme in Manchester. Financially, Gamgee soon found himself on a slippery slope, the ice proving expensive to produce and skaters put off by the mist which the cold ice in a heated room gave off. Gamgee’s first Glaciarium did not see the year out and by mid-1878 all his rinks had closed. His system, though, was used at the Southport Glaciarium which opened in 1879.

It was not until refrigeration technology became more advanced at the turn of the twentieth century that ice rinks become more viable.

February 20, 2022

Music Of The Week

If music be the food of love, play on, wrote Shakespeare in Twelfth Night. At The Trentham Monkey Forest near Stafford, the Park Director, Mark Lovatt, has hired a Marvin Gaye impersonator, David Largie, to perform some of the singer’s greatest hits inside the Barbary macaque habitat to put the females in the mood for love. Whether they monkeys will say “Let’s Get It On” for some “Sexual Healing”, and increase the monkey population, only time will tell.

Lovatt will be hoping for more success with his choice of music than authorities in New Zealand have had. In an attempt to disperse protestors who are camped outside the Parliament buildings in protest against Covid-19 vaccination mandates, they have bombarded them with Barry Manilow’s greatest hits and Macarena on a loop from one of parliament’s loudspeakers.

While it might have got me scurrying to the hills, the demonstrators are made of sterner stuff. Inevitably, James Blunt got in on the act, giving permission for You’re Beautiful to be blasted out on a loop. Rather than dispersing, the protestors put on their own music and had a party.

You can’t win ‘em all.

February 19, 2022

Art Critic Of The Week (5)

Most of us have an overwhelming desire to make an impression on our first day in a new job. An unnamed security guard, on his first day of duty at the Boris Yeltsin Presidential Centre in Ekaterinburg could not resist adding some finishing touches to Anna Leporskaya’s avant-garde painting entitled Three Figures which she had painted between 1932 and 1934.

He drew eyes on the faceless figures of the painting which formed part of an exhibition of abstract art. To make matters worse, he used a ballpoint pen provided by the gallery.

Leporskaya’s work is insured for £740,000, but, fortunately, the guard did not press too hard, and the damage was relatively superficial, the ink only slightly penetrating into the paint layer.

It took two visitors to draw a gallery employee’s attention for the additions to be noticed. The painting was removed from the exhibition to be touched up and the guard was fired.

February 18, 2022

Fourteen Of The Gang

Fashion comes and go and so, inevitably, slang associated with a particular look has a short shelf life too. Panniers were a form of women’s undergarment, wide and dome-shaped, so enormous that a woman wearing one could easily take up three times the space of a man. Inevitably, a woman wearing one would provoke some comment, giving rise to the 1880s term behindativeness, as in “that lady has got a deal of behindativeness”. Sadly, the term used to denote an exaggerated female form has long fallen out of use.

A belcher was a form of handkerchief featuring either light spots against a dark background or dark spots against a light background. It was named after the prize-fighter, Jim Belcher, who always entered the ring with a handkerchief with white spots against a background. Other fighters soon copied him, picking their own set of colour combinations. It was also the name given to a spotted tie.

To bell the cat was to risk taking the lead in some enterprise. It was Scottish in origin, a reference to a fable in which some enterprising mice plotted to put a bell around the neck of a cat so that they would know when it was coming but argued about who would take the lead. It also had an historical connotation. A group of Scottish nobles plotted to enter Stirling Castle and seize Spence, a favourite of James III, and hang him. Lord Gray asked who was going to bell the cat, the Earl of Angus volunteered and ever after was known as Archibald Bell-Cat, at least according to James Ware’s Passing English of the Victorian Era.

Baking has seen a renaissance in recent years. We are all familiar with the perils of a soggy bottom but what about a Bellering Cake? This was the name given to a plum cake where the fruits had sunk so low in the mix that they had to beller or bellow to make themselves known. I am sure it was delicious, nonetheless.

February 17, 2022

The Case Of The Dead Shepherd

A review of The Case of the Dead Shepherd by Christopher Bush

Before concentrating on writing full-time in 1931, Christopher Bush was a schoolmaster and he must have hated if it, if this book, the twelfth in his Ludovic Travers series, published in 1934 and reissued by Dean Street Press, is anything to go by. The Case of the Dead Shepherd, also known more curiously and inaccurately in America as The Tea Tray murders, is set a rather grim educational establishment, Woodgate Hill County School and the self-proclaimed shepherd is the unpleasant and deeply unpopular headmaster, Lionel Twirt.

Death visits Woodgate Hill twice in the space of minutes. Firstly, a history master, Charles Tennent, is found crawling on his and hands and knees, clutching a scientific catalogue, in his death throes having ingested some poison. Then the headmaster, late for his appointments, is found dead in the shrubbery with his head caved in. Are the murders connected and who did them? When it is established that Tennent had ingested a poison, oxalic acid, an unusual substance in murder mysteries, that was placed in a sugar bowl on a tea tray laid out for Twirt does the thought occur that Twirt may have been the intended victim of both murders.

There are many on the school staff who had reason to hate Twirt and discussions had occurred in the staffroom as to ways in which he could be despatched. Of the ancillary staff, Vincent, the groundsman, was always on the verge of dismissal and Flint, the caretaker, had gone missing at the time of the murders. Daisy Quick, the put-upon school secretary and daughter of the local police Inspector, had the opportunity and what about the visitors to the school, the governor, Mr Sandyman, and the mysterious Mela Ram?

The General, Superintendent Wharton of the Yard, invites Travers to help in the investigations. Usually in cases where a talented amateur and the professional police are involved in an investigation, they are in competition, reluctant to share clues and discoveries, with, inevitably, the amateur turning up trumps and showing the police up to be blundering oafs. Here, though, Wharton and Travers work in perfect harmony, and share the honours in solving the mystery.

Indeed, it is Wharton who works out why and by whom Tennant was poisoned, while Travers unmasks the culprit who caused Twirt’s demise, courtesy of an idea taken from a Chesterton story, and with a little help from his manservant, Palmer. The solution to the poisoning incident is particularly neat and took me by surprise. I had worked out who had murdered Twirt, there is being helpful and just a bit too helpful, but the how was intriguing.

Much of the investigations centred around the alibis of the many suspects at around the time of the two murders. When very precise timings need to be established and where there is no shortage of suspects, it can make for tedious reading in less skilful hands than Bush’s. Even so, those sections devoted to establishing alibis are a tad pedestrian in comparison with the rest of the book, especially when the reader realises that it may all be part of an elaborate red herring.

Nonetheless, the book is impressively well-plotted with no loose ends – even the roles of Sandyman, Flint, and Mela Ram are cleared up – and underlying the malevolent atmosphere of the school we find blackmail plots and overcharging. Handling a large cast list of potential suspects can be tricky, but Bush carries it all off with aplomb.

I enjoyed the book and look forward to seeing Travers and Wharton working in tandem again.

February 16, 2022

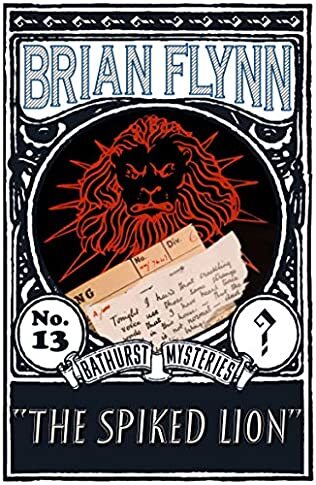

The Spiked Lion

A review of The Spiked Lion by Brian Flynn

By the time those of us who are following Brian Flynn’s series in chronological order have reached The Spiked Lion, the thirteenth in his Anthony Bathurst series, originally published in 1933 and now reissued by Dean Street Press, what we come to expect is the unexpected. Flynn once more changes his style and formula, producing a more conventional detective novel, but one that still surprises. There are elements of sensationalism to be found within its pages, making me wonder whether Flynn saw this as an attempt to integrate some of the racier elements to be found in pulp fiction into the more conservative form of Golden Age detective fiction.

And so we find a band of brothers who are identified and identifiable from a tattoo behind their left knee, a painting with strategically positioned holes, a vendetta, and an inheritance to claim. The deaths are particularly gory, the initial two victims who as well as being poisoned have all the hallmarks of having been attacked by a wild animal which, instead of claws, seems to have been armed with spikes – the spiked lion. Just to add to the fun, there is a third death, which has all the hallmarks of a classic locked room mystery and the dramatic, if somewhat melodramatic, finale has a fatal shooting. The body count is impressive.

Bathurst’s role is also intriguing. When we meet him at the start of the book, he has been invited by Sir Austin Kemble, head of police at Scotland Yard, to consider an unusual case, the death of an eminent cryptographer, Blundell, whose body had been found with serious and unusual injuries and betraying the tell-tale whiff of cyanide, and inside whose coat was a scrap of a note. Bathurst’s role is one akin to Sherlock Holmes, a detective who uses his brain and intuition to make sense of a puzzling set of clues and circumstances. This leads him to suggest that there be a search for another missing person.

This leads them to Wingfield, a distinguished heraldic expert, whose body is found near Sidmouth, bearing similar injuries to and the same whiff of cyanide as were found on Blundell. Bathurst’s role becomes more active at this point, particularly when there is a third death, that of Blundell’s nephew, poisoned in a locked room, in the home of Sir Richard Ingle. Ingle has a further disappointment when he learns that the title and inheritance he had thought was coming his way upon the death of his uncle, Lord Trensham, was being claimed by a son who had been assumed to have died during the war.

From a sedentary start Bathurst transforms into a man of action, putting himself in peril to unmask the culprits and resolve the mystery. In Flynn’s masterly hands he is the embodiment of the perfect all-rounder of a detective, smart enough to think through a problem but confident and brave enough to embrace the physical challenges with gusto.

That there is a conspiracy around the inheritance is clear around the midway mark, but what Flynn leaves cleverly in the air until the end is quite who the conspirators are amongst the suspects and quite what each of their games are. There is a connection between the Blundell, Wingfield, and the claimant to Lord Trensham’s title, but it is more prosaic than we originally are led to believe. Flynn revels in a spot of misdirection and he has ample opportunity with a clever plotline. And the spiked lion turns out to be menacing in more than one way.

There are some loose ends that are not satisfactorily explained, but, frankly, they hardly matter. Flynn has had some fun in producing a thoroughly enjoyable and entertaining story that keeps the reader’s interest throughout. For me, that is good enough.

February 15, 2022

The Sweepstake Murders

A review of The Sweepstake Murders by J J Connington

In a past life, I was an insurance underwriter and one of the first lessons I learned was that not only was precision of wording paramount but also the contract entered into with the client had to cover all eventualities. Sadly, no one in the party of nine gentlemen who decided to set up a syndicate to buy tickets in the Epsom Derby sweepstake was an underwriter or else they might have considered what happened if one or more of the participants died between the purchase of the tickets and the collection of the prize money, if any was won. Was it a Tontine scheme where the share of the deceased would be shared amongst the remaining participants or did the ticket pass to the deceased’s estate?

Perhaps the remoteness of drawing a ticket for a horse, never mind it finishing in a place, blinded the men to an obvious possibility, especially as they were all, save for the drunken Peter Thursford, in the prime of life. Inevitably, not only did one of their tickets draw a horse but the nag, not amongst the favourites, secured second place, netting the Novem syndicate £241,920 or around £16m in today’s terms. Inevitably, members of the syndicate started dropping like flies.

Curiously, as important as the issue of what happens to a deceased member’s share is to the premise of Connington’s seventh novel in his Sir Clinton Driffield series, originally published in 1931, it is not satisfactorily resolved. When Blackburn, the originator of the scheme, is killed in a flying accident, lawyers acting on behalf of his estate press their claim and the payout is embargoed by the courts. The members of the syndicate are divided as to how they should proceed, but as the story unfolds, the assumption is that it is a Tontine scheme, as Willenhall falls over a cliff edge, Coniston is killed in a car accident after accepting a bet and Peter Thursford is crushed by a car. Were these accidents really acts of murder and, if so, was the murderer one of the syndicate or the mysterious person or persons who had bought shares of individual’s tickets?

“Squire” Wendover is one of the syndicate, an awkward situation for him as news of the syndicate’s success and difficulties as he is a Justice of the Peace and sweepstakes were illegal, but he has the good sense to have been with Sir Clinton Driffield when Willenhall meets his maker and impeccable alibis for the times of the other deaths. He and Driffield do find Willenhall’s body and Driffield is sufficiently intrigued by the mystery to take interest in the case and to protect Wendover’s interests.

This is another of those Golden Age Detective stories where a knowledge of the obscurities of the Scriptures certainly helps. Willenhall was a keen photographer and the place where he met his death has enormous pillars of rock. Driffield makes a passing reference to the Dial of Ahaz, it appears twice in the Bible, in the second book of Kings and Isaiah, before he goes off. Inspector Severn is astute enough to recognise that light, shadow, and photography is at the heart of understanding Willenhall’s demise, but not perceptive enough to draw the pieces together to make a convincing case that demolishes the alibi of one of the suspects.

Driffield only returns late in the book, deus ex machina-like, to bring matters to a conclusion. Had he arrived earlier, the book would have been considerably shorter and, perhaps, one or more of the later deaths would have been prevented. While Driffield and Severn have reason to believe that the culprit was behind the other deaths they cannot prove it satisfactorily. Anyway, you can only hang someone once.

Wendover’s role is also reduced. He is a character in but not the narrator of the tale. He comes over as rather pompous albeit reliable and is a sounding board for Severn who views him as beyond reproach, despite his membership of the syndicate, After all, he does not need the money.

One of the standout insights of the book is the fascination with wireless, with characters going off to listen to a wireless, fiddling the dial to see what programmes they can catch from different parts of the northern hemisphere. A night-time radio session provides one of the members with his alibi.

Despite its flaws, this is an enjoyable story and once more Connington comes up with a fascinating, complex puzzle that is almost impossible for the reader to fathom, even if they are well-versed in the scriptures. He cannot resist the opportunity to parade his scientific knowledge. The culprit, though, despite the red herrings, is fairly obvious.