Martin Fone's Blog, page 111

September 12, 2022

How The British Discovered The Sea

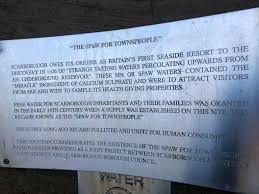

In 1626, about half a mile south of the harbour at Scarborough, Mrs Farrow spotted a spring trickling out of the cliff. Curious, she tasted the water and found that it had an acidic taste and “opened the belly”. She took the waters regularly herself and prescribed it to her friends when they were ill. It seemed to make them feel better. Word of its health-giving properties soon got round, attracting “persons of quality” to the North Yorkshire coastal town to take the Scarborough spaw.

Dr Robert Wittie, a physician from Hull, was an advocate of it, claiming that “it cleanses the stomach, opens the lungs, cures asthma and scurvy, purifies the blood, cures jaunders, both yellow and black, the leprossie and moreover a most sovereign remedy against hypocondriack, melancholy and windiness” (Scarborough Spa (1660)). Farrow’s discovery and Wittie’s boosterism put Scarborough firmly on the map, one of around forty-eight spas that were founded in England between 1660 and 1815.

Although the term “spa” was not coined until after the discovery of natural Chalybeate springs in the eponymous Belgian town in 1326, the Romans had enjoyed the benefits of mineral-rich spring waters in places such as Bath and Buxton. The fortunes of Bath’s spa were revived when the local bishop, John Villula, had it rebuilt in 1088 and soon, according to Gesta Stephani (1138), it attracted “from all over England sick people” who came to “wash away their infirmities in the healing waters”.

Temporarily banned by Henry VIII as a potential meeting place for Catholics, spas received a royal fillip when Elizabeth I, visiting Bath to grant it city status, declared that “the thermal waters should be accessible to the public in perpetuity”. She was an enthusiastic imbiber of the waters from Buxton and by the turn of 17th century taking the waters was a fashionable thing to do. Such were the low standards of personal hygiene, though, that attendants had to be employed to scrape the scum of the surface of the waters.

Rivalry amongst the spa towns was intense, but Scarborough quickly realised that it had a significant advantage; it was by the sea. Curiously, for an island nation dependent upon the sea for its economic prosperity, security, and its imperialistic ambitions, Britons were remarkably reluctant to step, never mind, plunge into it.

This all changed in the 18th century when physicians “discovered” the medicinal benefits of sea water. It was seen as a purgative and a cure-all, with patients being prescribed lengthy courses of imbibing sea water, often as much as a pint a day over the course of six months. To make it more palatable, it was sometimes mixed with milk and, for those unable to get to the coast, was sold by the bottle.

Exposing the body externally to sea water was also thought beneficial with physicians advocating a dip in the sea as part of a patient’s health regime. Early morning dips were especially favoured as the sea was at its coldest. Dr Richard Russell’s mantra of “the sea washes away all the Evils of Mankind” proved highly influential, especially amongst the upper classes. His practice, based in Brighton, transformed the once sleepy fishing village into a fashionable seaside resort.

We will another dip next week.

September 11, 2022

Theft Of The Week (11)

The keen eyes of a member of staff noticed that there was something different about the photograph of a scowling Winston Churchill. It had been taken by the famous Canadian photographer, Yousuf Karsh, in 1941 when Churchill visited Canada and had been presented to the Château Laurier hotel in Ottawa in 1998 where it has hung in a room ever since.

The staff member noticed that the frame around the photograph did not match those of the other five in the room and immediately alerted the manager. The hotel contacted Jerry Fielder, who oversees Karsh’s estate, and he immediately confirmed that the signature was a fake. It seems that a person or persons unknown swapped the genuine Karsh photo for a fake, although the hotel have no idea when the audacious change was made.

The Ottawa police are looking into matters.

If you have a large photo of a baby hanging in your room, make sure you inspect it thoroughly. After all, all babies look like Winston Churchill!

September 10, 2022

Twins Of The Week

Identical twin sisters, Brittany and Briana Deane, met identical twin brothers, Jeremy and Josh Salyers, at the annual Twins Day Festival, held, appropriately, in Twinsburg, Ohio. Cupid shot a pair of arrows into their hearts and their beaux both got down on their knees on February 2nd, 2018, to ask for their hands in marriage, presenting them with identical engagement rings. The date, 02/02, symbolised, they believed, a double proposal and a double marriage.

Obviously, they got married on the same day wearing the same outfits and there was only one place where the marriage could take place – The Twins Day Festival in Twinsburgh.

At this point what was quirky turned a little weird. They all live in the same house, in Bedford County in Virginia, with the menfolk working for the family lakeside wedding venue while Brittany and Briana work as attorneys four days a week for the same law firm in Roanoke. Both Brittany and Briana suffered miscarriages during their first pregnancies, but Brittany and Josh’s son, Jett, was born in late 2020, followed five months later by Briana and Jeremy’s son, Jax.

Marriages between two sets of twins are known as quaternary marriages and the offspring, both cousins and brothers, so close are their genetic makeup, are known as quaternary twins.

Variety is not for some folks, it seems.

September 9, 2022

A Minor Operation

A review of A Minor Operation by J J Connington

I have long been fascinated by the impact of the state of a painter’s eyesight on the type and style of paintings that they produce, an examination of the difference in style and approach in the early and later works of J M W Turner being a classic example. In A Minor Operation, the eleventh in Connington’s Sir Clinton Driffield series and originally published in 1937, cataracts and their impact on an artist’s style provide a major clue that leads to the resolution of an intriguing mystery.

Connington is a master of complex plotting, red herrings, cast-iron alibis, and misdirection while, at the same time, playing fairly with his readers. We may not have a mind as mercurial as that of the Chief Constable, but we do have all the clues presented to us, some perhaps a little opaquer than others, and are able to see how they all hang together and why some initially promising leads lead nowhere. This book is a classic example of Connington at his best.

It begins as a tale of three convicts, Nicholas Adeney, whom we meet in the first chapter, who along with Deerhurst, whose shadow casts a long shadow over the plot, were jailed when their firm collapsed, and petty thief, Sturge, who is more of a bit character, who served time with the other two and resented Deerhurst for putting a spanner in his plan to offer fellow prisoners their liberty earlier than was the King’s pleasure. Deerhurst is married to Nicholas’s sister, Hazel, who wants to divorce and is planning to provoke Deerhurst upon his release to attack her in order to resume her previous relationship with an artist.

After Deerhurst’s release, Hazel’s maid discovers that her mistress is missing and that there is a small pool of blood in the drawing room. Deerstone’s body is eventually found in a secluded patch of road, having been run over, although he had earlier been hit over the head and stabbed in the chest. Sir Clinton Driffield, accompanied by his faithful Dr Watson-like “Squire” Wendover investigates and soon discovers that Hazel had left, having only taken undergarments.

Nicholas Adeney does not help his cause by taking an antagonistic stance. He had access to Hazel’s house and was seen in conversation with Sturge about the latter’s child who has eye trouble, although his alibi for the supposed time of Deerhurst’s demise seems sound. Had Hazel lured Deerhurst to the house with the telegram found in his possession and killed him, with perhaps Adeney helping to move the body, but then why had she left with only undergarments packed in a case?

Driffield finds a number of clues which, initially, seem baffling, including an electric clock which had stopped for precisely 3 hours and 44 minutes, a Braille typewriter, a pile of red lead, and an envelope containing bearer bonds to the tune of £500. Hazel, who was paranoid about fires, turned the electricity supply off when she went to bed. Who turned the power back on and why?

Love letters, the reading of which causes the Squire some serious moral qualms, a careful examination of the paintings in Hazel’s house, and the intervention of two lawyers lead Driffield to suppose that the case is less about marital relationships and more one of the consequences of the collapse of Adeney and Sons, for which both Nicholas and Deerstone were jailed.

Connington, being a chemistry professor and obsessed with the minutiae of criminal cases, revels in exploring the differences between the typefaces of different models of typewriters of the same make and the impact of using carbon paper and allows Driffield to perform a clever chemical experiment which reveals a surprising result and provides proof positive of the identity of the culprit and their motivation.

I thoroughly enjoyed the book and for once did not find Driffield’s bumptiousness overbearing. Old-fashioned Connington may be, but he knew how to construct an intriguing mystery.

September 8, 2022

One Gin Sage Premium London Dry Gin

One Gin Sage Premium London Dry Gin is another one of those gins that I picked up on a recent trip to the headquarters of Drinkfinder UK in Constantine, down in Cornwall, although it is not Cornish in origin. Rather it is produced near the smoke in Richmond-upon-Thames. As is the modern way, it has an ethical and sustainable twist to its back story, one that, intriguingly, has its roots in water.

Hurricane Mitch was the second deadliest Atlantic hurricane on record, sweeping through Central America in 1998 and causing around 11,000 fatalities, seven thousand of whom were killed in Honduras. In Honduras at the time was Duncan Goose and his exposure to the aftermath of the devastation wrought by the hurricane brought home to him the importance of having access to safe drinking water. On his return to Blighty he gave up his job and launched the ethical bottled water brand, One Water, whose profits fund the provision of drinking water in developing communities.

Out of Goose’s endeavours rose the One Foundation, a registered UK charity, and on World Water Day in 2017, March 22nd, One Gin was launched. In line with the One mission, at least ten per cent of its profits go towards funding clean water projects, another example of indulging in your favourite tipple and making a difference elsewhere.

The bottle is cylindrical, slightly taller at the top at the bottom, with a broad shoulder and a medium sized neck which leads to a wooden stopper with a cork. The label design is busy, using greens, beige, and copper as its principal colours. Its main logo is a butterfly which appears three times, on the label, on the neck, and on the stopper. It references the well-known trope of chaos theory that the tiny flutter of a butterfly’s wings can trigger a cyclone on the other side of the world and is symbolic of the aspiration that a single small act can make a difference.

Laudable as that sentiment is, the bottle’s design is a little muted for my taste and would find it difficult to make its presence known on a crowded shelf. It was no surprise when I learned that they had completely redesigned the bottle into a more elegant shape and used a distinctly art deco approach to their labelling. Clearly bottle 356 from batch number 15 is old stock.

The redesigned One Gin bottle

The redesigned One Gin bottleThe idea was to use a flavour profile that used tastes and smells that were natural to England. As the name of the hooch suggests, the showcase botanical is sage which at first blush seems a bold choice given its strong flavour, earthy, slightly peppery with hints of mint, lemon, and eucalyptus, but these are all flavour elements that work well with juniper in a gin. Annoyingly, I have not been able to find a definitive list of all the botanicals that go into the mix and so have had to rely on my slightly battered senses of smell and taste.

On the nose there is no doubt that the main flavours are sage and juniper, both powerful aromas that jostle for pole position, although there also hints of nuts and what smells distinctly like marmalade on the margins. In the glass the spirit is clear, and in the mouth, it is a gloriously complex mix of juniper, sweet and dry citrus, and with spicy elements that become more apparent in its warm, smooth, savoury finish. It worked well with a premium tonic, do not go for an overly lemony one as there is enough in the spirit to be going along with. The sage worked well with the juniper and was an imaginative choice of botanical that sets the spirit apart from its many rivals.

Now they have sorted the presentation out, I expect One Gin to go places.

Until the next time, cheers!

September 7, 2022

Holy Disorders

A review of Holy Disorders by Edmund Crispin

Apart from the odd short story I had not read any of Bruce Montgomery’s works, Edmund Crispin is his nom de plume, so this was a step into the unknown for me. This is the second of his novels to feature the eccentric Oxford don, Gervase Fen, who is the series detective and was originally published in 1945. The publication date is important as, although this is a murder mystery involving priests and organists, the Second World War in the form of German collaborators plays an important role in the unfolding of the narrative.

At the outset, it seems to be a straightforward, slightly twee, very funny, tale of ecclesiastical jealousy, rivalries, intrigue, and murder. Set in the cathedral city of Tolnbridge where Fen is holidaying, pursuing insects. He sends a telegram to Geoffrey Vintner, a composer who plays the role of his Dr Watson, to come down as the organist has been attacked, oh, and to bring a butterfly net. This unwieldy piece of impedimenta generates moments of pure comedy and farce as Vintner struggles to make his way to the West Country, ignoring an anonymous letter warning him off and several attempts on his life and picking up a minor Earl called Henry Fielding along the way, whose principal purpose seems to be the feed for a gag about Tom Jones.

The organist is poisoned, on the first occasion only sufficiently to hospitalise him but the second time, in the hospital itself, successfully. There is a second death in the cathedral, the victim found in the tomb of a dead bishop, having been hit by a tombstone. If this is not enough to be going on with, the plot veers off, rather like a Gladys Mitchell story, into the world of witchcraft, the bishop whose tomb is in the cathedral was a notorious witchfinder, coupled with international espionage and German collaboration and child abuse. The latter theme, the grooming of a young girl who is drugged with marijuana, is rather treated as a minor subplot, but to modern readers is probably the most disturbing element of the book. Clearly not all is well within the cathedral’s precincts.

Fen realises that there is, or at least was, something in the vicinity of the organ and the bishop’s tomb, the discovery of which was life-threatening and that certain parties had to go to some lengths to remove it. Fen is on a mission to discover what it is and who are behind the murders and the plot. He works his way through a bewildering number of suspects and at some peril to his own life, eventually rumbles what is going on.

I am not quite sure about Fen as a central character. He is eccentric, ego-centric, smug, abrasive, tolerated only because he is able to cut the Gordian knot and solve a mystery that baffles mere mortals. However, he is not a character that I warmed to and seems to be a pastiche of many other amateur sleuths I have encountered. Indeed, it is hard not to conclude that the book is a pastiche of the detective fiction genre, drawing inspiration from a wide range of influences. My favourite two are the nod to Edgar Allen Poe when Fen and Vintner visit the gloomy cleric Garbin who has a pet raven and a wife called Lenore and a couple of pubs whose names Brian Flynn would have been proud of, The Whale and Coffin and the Three Shrews. There is even the obligatory love interest as confirmed bachelor Vintner takes a shine for Frances Butler, only to be sadly disillusioned.

The narrative is strewn with literary references and quotations and although Crispin wears his intellect on his sleeve, sometimes using vocabulary that tests the knowledge of even his most literate of readers, it is never being clever for the sake of being clever. His book is a riot from start to finish, gloriously funny, sometimes bonkers, occasionally dark, often perplexing, and with the happy knack of creating a world that you can immediately immerse yourself in and forget reality. Terrific stuff.

September 6, 2022

Dead On Time

A review of Dead on Time by Clifford Witting

Clifford Witting is another one of those Golden Age detective fiction writers whom popular tastes, rather unfairly, have despatched into obscurity. He writes with some flair, not a little wit, usually making the reader smile on every page with either a finely tuned sardonic turn of phrase or a sharp observation and can produce a fascinating impossible murder that keeps his reader intrigued. Dead on Time perfectly showcases his skills.

Originally published in 1948 and the eighth in his Inspector Charlton series, not all of which have been reissued, sadly, the scene of the crime is an English pub, the Blue Boar, where the local police are gathered to celebrate the retirement of Sergeant Martin. Their reverie is interrupted when the local drunk and ne’er-do-well, Jimmy Hooker, bursts into room clearly desperate to pass on some information but then has second thoughts. Moments later, when he has returned to the public bar at closing time which was ten o’clock in those days, Hooker is collapses, poisoned with cyanide. Charlton’s job is to find out who the culprit is and how the poison was slipped into Hooker’s tankard.

Hooker’s favourite tipple was mild and bitter – ah, the good old days – which he drank out of a tankard and which he had topped up (frequently) when he got half way down. While he was out of the bar, one of the topers, Winslake, was seen pouring a gin into Hooker’s tankard. As the obvious suspect and having caused a disturbance subsequently in the pub, he was arrested, especially as he was seen to have been in an animated conversation with Hooker to whom he owed some money. To the police’s profound embarrassment, though, he too is poisoned, some poison slipped into his porridge supplied by an outside caterer, apparently at the request of his mother, poison while in his police cell.

Witting supplies a plan of the pub, which is worth studying in order to keep track of the movements and check the alibis of the suspects as they move around the rambling collection of rooms. Amongst those who are interviewed are a married couple who have had previous with Charlton and a marvellous heel and brimstone evangelist in the form of Zephaniah Plumstead. It gradually dawns on Charlton that the key to solving the two murders lies in the information that Hooker was going to impart to the police.

Around the half-way mark, the book, which was ambling amiably along as a hybrid of an impossible murder and police procedural, takes a sudden and unanticipated turn, plunging the reader into the murky world of criminal gangs and jewellery heists. We learn that a priceless collection of Indian jewels is landing at the nearby port of Southmouth to be transported to London and that there is a plot to hijack the convoy. Motivation for the murders established, the focus of the book becomes more of an inverted mystery.

The story reaches a thrilling finale with a police operation, working in cahoots with the Army, to thwart the hijack and arrest the minions, before Charlton reveals who committed the murders and, more intriguingly, how. The way Hooker was murdered seems deceptively simple, but often the simplest ways are the best. The culprit, too, will surprise many a reader, although seasoned hands of the genre might have got there by a process of elimination.

The join in the plot line is a bit too clunky to make this a classic, but it is is thoroughly enjoyable and entertaining. Perhaps specialist reissue publishers will help the growing band of Witting aficionados complete the set.

September 5, 2022

The History Of The Race For Doggett’s Coat and Badge

On August 1, 1715 six watermen chosen by lot, who had completed their seven-year apprenticeship during the previous year, accepted Thomas Doggett’s challenge and rowed their heavy wherries along the 7,400-metre stretch of river from the site of the Old Swan Tavern by London Bridge to the Swan Inn at Cadogan Pier in Chelsea. Rowing against the tide and taking more than two hours of strenuous effort to complete the course, it was a test of endurance and skill. John Opey of Saviour’s Hill, the winner, received a scarlet coat with a solid silver badge on the sleeve showing a leaping horse and the word “Liberty”, as well as a matching cap.

Doggett organised the race each year until his death in 1721. Anxious that the race would not die with him, his Will required his executor, Mr Burt of the Admiralty Office, to establish a Trust to provide annually ad infinitum “five pounds for a Badge of Silver representing Liberty, eighteen shillings for a Livery on which the Badge was to be put, a guinea for making up the suit of livery and buttons and appurtenances to it, and 30 shillings to the Clerk of the Watermen’s Hall”.

Burt, though, was reluctant to assume Doggett’s mantle and passed responsibility and the Trust of £300 to the Fishmongers’ Company, who have organised the race since 1722, although from 2019 they have shared the task with the Company of Watermen and Lightermen. It is Britain’s oldest continuously held rowing race, leaving its more famous Thames rival, the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race, first held in 1829, trailing in its wake.

The winner still receives a coat and badge to Doggett’s design at a ceremony held at Fishmongers’ Hall. To a fanfare of trumpets, they, together with the Clerk to the Company and Bargemaster, are escorted into the Hall by past winners dressed in their coats and badges. The Clerk describes the race in suitably Homeric style, the Prime Warden drinks to the victor’s health, and then the winner is escorted out to the strains of Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary.

There have been some changes along the way. The race is no longer held on August 1st, the date set according to tides and river conditions. In 1873 the course was reversed, allowing oarsmen to take advantage of the incoming tide. This decision, together with the use of single scull boats, reduced the time to complete the course by three quarters, Bobby Prentice setting the race record of 23 minutes and twenty-two seconds in 1973. Not everyone was enamoured with the change, one contemporary thundering that “this deplorable decision to go with the flow obviously marks the start of the subsequent sustained decline in the British national character”.

The Second World War only put a temporary halt on the race. Suspended during hostilities, nine races were held in 1947, one for each of the years that those completing their apprenticeship were unable to enter. This imaginative solution ensured an unbroken roll of winners from 1715, a precedent followed in 2021 when two races were held after the 2020 event fell foul of Covid restrictions.

In 1988, because of the decline in numbers of watermen and apprentices, the qualification criteria were changed to allow competitors to enter within three years of completing their apprenticeship. The first woman to compete, Claire Burran, came third in 1992.

The 308th Doggett Coat and Badge Race, scheduled for July 19th this year, hit choppy waters when the extreme temperatures led to its postponement. It was eventually held on July 28th with George Gilbert of the Poplar Blackwall and District Rowing Club, who had returned for his final attempt, finishing ahead of first-time entrant Matthew Brookes. The indomitable spirit of the watermen lives on.

September 4, 2022

Leak Of The Week

When nature calls, it must be answered, or was this a case of taking the piss?

During yesterday’s First Qualifying Round of the FA Cup between Blackfield & Langley FC and Shepton Mallet FC history of sorts was made, when the home side’s goalkeeper was sent off in the 76th minute after the referee spotted him urinating in a hedge behind the goal. It is thought this is a first in the competition’s long history.

The drama was not over. A disagreement on the touchline later saw one of the Blackfield coaching staff shown a red card and one from Shepton Mallet.

Unlike their goalie, Blackfield managed to hold out until full-time to secure a 0-o draw. The replay will take place on September 6th and Shepton Mallet have already started looking for a portaloo supplier to sponsor the game.

Perhaps Blackfield should erect a plaque on the spot to commemorate a piece of FA Cup history.

September 3, 2022

Number Of The Week

On a weekend where Liverpool and Glasgow Celtic recorded a cricket score in beating AFC Bournemouth and Dundee United respectively nine nil, the fourth XI of Elvaston Cricket Club scored, well, a football score when they were bowled out by Risley Cricket Club’s second eleven for just nine runs. To make matters worse, seven of the runs came from extras, five leg-byes and two wides.

Only Will Hobbs troubled the scorers, recording two runs, while nine of his colleagues recorded ducks and Blake Hall was nought not out. Inevitably, Risley won the match by ten wickets.

To view the scorecard, follow the link below:

https://elvaston.play-cricket.com/website/results/5014304

Elvaston’s single figure innings total is not the lowest score recorded in cricket history. That dubious honour goes to Huish and Langport who, in 1913, failed to score a single run when they were bowled out by Glastonbury.