Jack Messenger's Blog, page 7

March 8, 2018

Farewell Olympus (2)

Eric drew close, as if confiding a secret. ‘The word is dead, Howard. It died when facts ceased to count. Perceptions are all that matter these days. Electronic impulses have no conscience. Money talks – I should know – but it’s mostly lies.’

The post Farewell Olympus (2) appeared first on Jack Messenger | Feed the Monkey.

Michael Raship | The Anarchist Thing to Do

[image error]

The Revolution Will Not Be Televised: Book review of The Anarchist Thing to Do, a novel by Michael Raship

Michael Raship’s first novel, The Anarchist Thing to Do, is an accomplished, delightful and engrossing book, full of gentle comedy, sadness and hope. Its story parallels the social changes spanning the 1960s to the 1980s within the United States, as revealed in the evolution of a radical anarchist family of hippies: parents Kaye and Horton, children Skye and Jude.

Skye narrates the story of her family, commencing with childhood memories of life in a Vermont commune, before a relocation in 1975 to Glendale, momentous in its consequences. In Glendale, Horton and Kaye run the White Elephant, a second-hand store and venue for classes on anarchist political theory and vegetarian cooking, meditation and poetry, even belly dancing.

All families have their internal mythologies, comprising the stories they tell in order to understand themselves and their interrelations. When a family regards itself as outside mainstream society and is fundamentally opposed to all forms of authority, its mythology has to be particularly robust. Thus, Skye begins with a familiar family tale:

The story of my family, as it was told to me and my brother Jude when we were children, began with myth and magic. ‘Kaye used to be a genie,’ Horton would say to us. ‘Honestly. That was how we met.’

Horton and Kaye were anarchists; our family was an anarchist family. These basic facts motivated everything we did. Until Jude and I were six, our whole world had been Far Gone Farm, a hippie commune in the Vermont woods where everybody tried to live according to the political ideals that Horton had outlined in his book, The Principles of Contemporary Anarchism.

The children’s complete acceptance of this lifestyle and the commitment to anarchist ideals it entails comes across almost as a state of grace, an edenic innocence amid a corrupt and unjust society. Not at all sinister, it is in fact humorous and strangely moving, in part because the philosophy of anarchism is so anti-authoritarian that nothing feels imposed on anyone. Skye and Jude’s journey to adulthood gradually exposes the faultlines running beneath the surface of this way of life, culminating in a more clear-eyed, forensic examination of their parents that leads to partial disillusionment, tragedy, disaffection and then to redemptive reconciliation.

Thematically, The Anarchist Thing to Do is concerned with the passing of time and what it does to a family and a nation. As the political and social triumphs of the 1960s and 1970s – the civil rights movement, feminism, popular protest against the Vietnam War – recede into history, and the era of Reagan and conservatism sweeps all before it, how are ideals preserved and hope kept alive? When exactly do the music and the clothing, the long hair and the drugs, cease to function as revolutionary alternatives and instead become mere exercises in nostalgia disguising powerlessness, defeat and a refusal to engage with new realities?

Only the children can begin to answer these questions. At one point, an encounter between Skye and Jude after they have left their family home in Glendale is described in terms of unlikely survival:

… we regarded one another with the disbelief of survivors meeting again after separate miraculous escapes from calamity.

Skye’s first boyfriend is made to bear the weight of her need to escape the past:

I loved and needed him so much that he seemed exempt from generalizations that applied to the rest of humanity.

As these brief extracts indicate, The Anarchist Thing to Do is immensely readable in a way that reminds me of Salinger, whose shorter works are particularly admired by Skye and Jude – I suspect because their descriptions of family life are as eccentric, hermetic and all-encompassing as their own. Embedded in a rich tradition of American storytelling, The Anarchist Thing to Do is a thoroughly enjoyable and rewarding book, written with great assurance by an author who rarely puts a foot wrong. I thoroughly recommend it.

Zowal Books | ISBN 9780998470801 (pbk) | ISBN 97800998470813 (ebook)

#social-sharing-cf686435c728932e6592faa5f0551525{

width: 780px;

}

#social-sharing-cf686435c728932e6592faa5f0551525 li{

text-align: center;

}

The post Michael Raship | The Anarchist Thing to Do appeared first on Jack Messenger | Feed the Monkey.

March 6, 2018

Farewell Olympus

I once played volleyball with the archbishop of Barcelona. He was fast around the court and had a useful serve. Attired in clerical garb and sporting a long dark beard that waved in the wind, he looked like somebody impersonating himself. I know a little about how that feels.

The post Farewell Olympus appeared first on Jack Messenger | Feed the Monkey.

February 22, 2018

Fires | Tom Ward

A Burning Rage: Book review of Fires, a novel by Tom Ward

Novel titles are seldom as apt as Tom Ward’s Fires, which follows Guy, a firefighter in a town dominated by its vast steelworks, and Nathan and his friends, teenage arsonists whose lives are otherwise foreclosed by poverty, corruption and ‘the system’. Guy and Nathan’s paths eventually cross in expected and unexpected ways – most of them fiery – in an intermittently compelling narrative suffused with anger and loss.

The unnamed town in Fires is decaying due to neglect and poverty. The rich live in gated communities above the urban sprawl that is filled with abandoned civic buildings and row upon row of boarded houses. Increasingly vociferous and angry protestors march through the streets: there are shady goings-on at the steelworks, and jobs are dwindling. People are frightened. Lives and livelihoods are at risk.

This non-specific scenario is oddly timeless – deliberately so, I believe. In the context of the UK, a town wholly dependent on the production of steel harks back many decades, before the domination of China and elsewhere. Yet the gated communities, vacant tower blocks and fast-food outlets described in Fires sound contemporary. There is little sense of a surrounding nation, and the anonymous town is a self-contained entity that exists in a vacuum suggestive of wider catastrophe: one pictures everywhere else as cloaked in impenetrable night.

There are comparatively few novels devoted to firefighters, so it is interesting that Fires should resonate so strongly with Henry Green’s Caught (1943), which is also an urban tale, this time of the Auxiliary Fire Service during the London Blitz. Caught is similarly pared down: its principal characters are sparely named Pye and Roe (PyeRoemania?), and its narrative trajectory is as grimly inevitable as Fires. The writing style of Caught is extremely odd: error-strewn and infelicitous sentences that cumulatively become incantatory, hieratic. As one perceptive reader–reviewer has said of Caught, it’s not an enjoyable read, but it feels like a necessary one. He or she might have much the same feeling about Fires.

Stories echo forward and back, and fire itself is a potent and ambiguous cultural metaphor: a warm and caring friend when safely contained; a devil of destruction and pain when it escapes our control. Whether ignited or fought, fires rage through Fires, consuming property, lives and possibilities. For Guy, dedication to fighting fire has consumed his life; for Nathan and his gang, arson provides a power and freedom, a terrible beauty, rarely experienced in their world of dead-end jobs and dreary routine.

Coincidentally, it’s here that another Green(e) is evoked, for Fires conjures a close cousin to Greeneland, populated by isolated individuals contemplating their past with regret and their future with paralysis. Guy’s feelings of guilt are like those of Rowe (another one) in The Ministry of Fear (1943, again). In addition, the urge to destroy that propels Nathan and his gang is shared by the children in Greene’s short story The Destructors (1954).

Fires is less successful when considered in isolation from its illustrious forebears. In my opinion, it is too long, so that the story seems slackly spun out. And there are just too many fires: by the time I’d reached the sixth or seventh descriptive passage about explosions of flame and falling masonry, it was difficult to feel involved. With some judicious pruning and an injection of momentum, the novel would have felt much more urgent. Alternatively, if conversations and/or contemplations had been more creative and provocative, the novel would have filled the space available. As it is, the plot outcomes are unexpected but unsurprising. The prose tends to be flat and hurried, with an irritatingly absent comma before the coordinating conjunction then, plus other minor errors.

Despite these problems, much of the novel is strangely compelling. I read it quickly because I was caught up in the ambiguities of time, place and meaning, its principal achievements.

Crooked Cat Books | ISBN 9781548701642 (pbk) | ISBN none (ebook)

#social-sharing-5900f9969b6979e252f6a9bb7adc6afd{

width: 780px;

}

#social-sharing-5900f9969b6979e252f6a9bb7adc6afd li{

text-align: center;

}

The post Fires | Tom Ward appeared first on Jack Messenger | Feed the Monkey.

A Mentor and Her Muse | Susan Sage

No Way Home: Book review of A Mentor and Her Muse, a novel by Susan Sage

‘I wouldn’t classify what I did as a crime, rather as a sort of vigilante justice’, proclaims the intriguing opening line of A Mentor and Her Muse. Thus are we introduced to the moral and emotional uncertainties that haunt schoolteacher Maggie, the story’s central protagonist. They also haunt the novel itself, for good and ill.

Taezha (Tae) and Maggie both live in Flint, Michigan, a town whose fortunes declined precipitously when the auto industry shut up shop without a backward glance or moral scruple. Maggie is a white schoolteacher and prolific serial monogamist; Tae is a talented and beautiful black schoolgirl. Maggie has some money and freedom; Tae has little of either. Maggie’s parents killed themselves, and she herself once attempted suicide and is something of a kleptomaniac. Tae’s family circumstances are difficult and stressful; her mother, Quintana, is fickle and conflicted.

Maggie and Tae first meet when Tae is twelve, and Maggie is immediately smitten in ambiguous ways that are supposed gradually to untangle as the story unfolds. Tae is almost fifteen when Maggie takes her on a road trip, more or less with Quintana’s permission. This trip forms the spine of the story. ‘Tae is not Maggie’s Lolita!’ exclaims the authorial voice at one point, although Humbert Humbert’s travels with his underage victim have long since been evoked. Maggie cloaks her need to be with Tae in concealing clichés: ‘We both realized, without telling ourselves or each other at the time, that we needed each other as central players in our lives.’

Structurally, the novel alternates interestingly between third person and first, between Maggie’s journal entries (dating back decades to race riots in Detroit and tensions with her conservative parents) and Tae’s adolescent poems, with frequent changes of tense and perspective.

However, there is also a lot wrong with A Mentor and Her Muse, and its many problems are mutually reinforcing.

All authors have their little writerly tics and subconscious habits. The practice of writing necessarily includes constant effort to bring these habits to creative awareness. Only then can we place them under our command. Susan Sage has a lot of them, in my view, and they need to be disciplined. Together, they add up to a confusing and disappointing experience.

To begin with, the text could do with careful proofreading: there are more than enough errors to irritate the most patient reader. Missing words and garbled sentences abound; at one point, ‘eluded’ is used when ‘alluded’ is meant; a gazebo is severed into ‘two halves’.

Explanatory clauses and qualifying statements in parentheses (like this) run amuck, page after page. Throughout, swarms of self-referential questions infest passages of free indirect discourse, concluding paragraphs or else nesting in their midst. This overuse of an otherwise effective rhetorical device becomes wearing and predictable, so that it ceases to function. Eventually, about half-way through the book, they become merely amusing, as we wait for their inevitable arrival.

Themes of race and age, love and creativity struggle in vain for precise articulation throughout A Mentor and Her Muse. ‘What is this white woman up to?’ asks Tae of Maggie, but the question is hopelessly underdetermined. Maggie is, I think, meant to be taken seriously, but she is irritatingly naïve: ‘So I, too, have known something of racism and discovered what a hell on earth it truly is!’ For a middle-aged white woman like Maggie – no matter how observant, sensitive and ‘concerned’ – to make such a claim is frankly derisory, particularly as it is uttered after a marginally uncomfortable experience at a school committee meeting. Hell indeed.

A Mentor and Her Muse would benefit from a lot more dialogue. Assertions of states of affairs become dull and repetitive when they are used to the exclusion of so much else, depriving us of artistry and nuance. These assertions are hurled at the reader, many of them out of nowhere, and we have to take them on trust.

‘As much as Tyler wishes he could spend more time with Tae, it’s been amazing getting to know Maggie.’ There is precious little evidence for this amazement: if only Tyler had been allowed to say this for himself, so that we could see his feelings grow; if only we could know that his heart beat quicker and his eyes shone. But we don’t. Similarly with ‘More than once he’s thought about putting the place up for sale, much as he hated to even think of it.’ If he’d only expressed these doubts to someone, so we could see them evolve, then they would become real. But they’re not.

Maggie’s sister Caroline arrives for reasons best known to herself, at which point there is potential for conflict and dramatic interaction. Instead, we are provided with more dull exposition.

We don’t get to know any of these characters because they seldom reveal themselves in any other way. Thus, Sulie, a relatively marginal character, is a mix of personality traits and motivations that make her ridiculously unbelievable and incoherent. Maggie and Tae’s compulsion to write seems like empty and self-important posturing.

Every bit of information this stylistic approach conveys is given the same emotional weight. It fails to provide a path through the narrative: everything becomes equally unimportant, with no highs or lows, and the reader ceases to care. That’s a great shame.

Open Books | ISBN 978 061572 2801

#social-sharing-c34d470299f1c91877a4d37c4db882ed{

width: 780px;

}

#social-sharing-c34d470299f1c91877a4d37c4db882ed li{

text-align: center;

}

The post A Mentor and Her Muse | Susan Sage appeared first on Jack Messenger | Feed the Monkey.

February 15, 2018

The Writing Greyhound: Finding Meaning in the Stories We Love

‘People invite me to their literary evenings just to get the name of my tailor.’

I am the Writing Greyhound – pleased to meet you. I’m hosting a post of Jack’s from 15 February entitled ‘Creative Reading: How We Find Meaning in the Stories We Love’. It’s about some of the ways we read and observe important things in the books we enjoy. As a writer myself (Lou Canino, author of the Matt Blasco detective series), I found the post provided interesting food for thought. Speaking of food …

The Writing Greyhound is a great book blog. You can find it here.

The post The Writing Greyhound: Finding Meaning in the Stories We Love appeared first on Jack Messenger | Feed the Monkey.

February 9, 2018

Literary Homicide with TropicalMary

Go there, if you dare, for an excellent review of Four American Tales.

The post Literary Homicide with TropicalMary appeared first on Jack Messenger | Feed the Monkey.

February 1, 2018

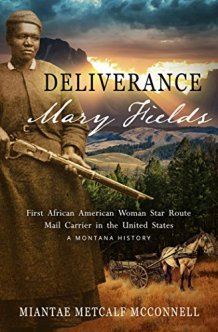

Deliverance | Miantae Metcalf McConnell

Striving to Deliver: Book review of Deliverance, a novel by Miantae Metcalf McConnell

The front cover of Deliverance proclaims Mary Fields (c. 1832–1914), the putative subject of the novel, ‘First African American Woman Star Route Mail Carrier in the United States’. The cover also announces that this is ‘A Montana History’.

Mary Fields had been born into slavery and was only freed with Abolition. She must have been a woman of great determination and perseverance, for she won the respect and friendship of the communities she served, and was an independent businesswoman. ‘Black Mary’, as she was known by many, even became the ‘mascot’ of a local baseball team. She did not become an employee of the US Post Office; rather, in common with other persons, she was contracted to deliver the mail on a specified route based on her initial bid, her guarantees and her dependability. In 1885 Mary was awarded the contract to deliver mail from Cascade, Montana to St Peter’s Mission.

Not a great deal else is known about Mary Fields, but Miantae Metcalf McConnell has undertaken extensive research into her subject and has added to our knowledge of this redoubtable woman. One of McConnell’s stated ambitions in writing her novel is to enable Mary to become ‘an inspiration to all peoples: past, present and future’. Therein lies a problem.

When novelists begin to consider a project, they seek an answer to an important question: is there a novel here? In this case, is there a novel here that can comfortably extend over a thousand pages (as measured in iBooks)? In my opinion, the answer to both these questions is an emphatic ‘no’.

The paucity of information on Mary Fields has inspired McConnell to add, and add, and add to her narrative, expanding it to bloated proportions, so that it is shapeless and unorganized, despite the appearance of structure provided by part titles, intertitles, section breaks, and prologue and epilogue. The impressive bibliography of works consulted by the author seems to have unleashed a torrent of prose unrestrained by a guiding intelligence that should have been screaming ‘Enough already!’ An author too attached to her subject, too excited about telling the whole truth, and intoxicated by her historical milieu will inevitably lose all sense of proportion: everything is precious, and all her inventions are vital. The avowed motivation to inspire readers lays a dead hand on creativity, on balance, on history.

Deliverance is rife with confusions that begin with the plethora of titles/subtitles/straplines on the front cover, leaving readers in doubt as to what kind of book they are meant to be reading. That doubt, it seems to me, is shared by the author, whose prologue is an epically misjudged venture into geological prehistory. There follows an eighty page account of Mary struggling through a snowstorm, eventually leading to a search party and recovery. This section is interminable and completely typical. I thought myself entitled to expect a book about Mary, but lo! there are all these other interesting characters we simply must follow, endlessly and in tedious detail.

As for the writing itself, McConnell has an excellent vocabulary, which she displays at every opportunity, often at some cost to intelligibility:

Blasts of noise screeched. Flesh lunged, shrieks wailed …

Beads of sweat pimpled her forehead …

Overhead, an onslaught of pewter clouds gestated into columns. Whiffs of dry air whirled across snow mounds, quipping tiny crystals airborne. Dusk retreated. Legendary north winds, known for hurling glaciers, amassed and fisted, launched into fury …

Striated layers of mist hung at ground level.

This is irritatingly overwritten and stuffed with pleonasm. McConnell invariably goes for the unusual word (heads can’t simply turn or twist or jerk, they must ‘torque’), and her predilection for the missing conjunction is confusing. Reading this stuff is exhausting: the mind longs for straightforward, concise prose without artifice.

Alone with herself, Mary is much given to uttering helpful contextual remarks designed for the reader’s benefit:

Guess it’s a bona fide town with the new post office. Got one store, one church, one schoolhouse, two sheep sheds, and three saloons – looks like a tintype of life sequestered in the wild and wooly. Yep.

‘Yep’ indeed. Surveying the wintry landscape, she lets us know that ‘Folks came thinking it was gonna be easy’, a sentiment I soon came to appreciate as I struggled valiantly through another hundred pages of deep narrative drifts and icy squalls of description.

As if the novel’s massive cast of supporting characters were not already more than enough, room is made for the souls of the dead and apparitions of younger selves, the latter of whom speak in pious platitudes to their older avatars:

I am here because there is still hurt inside you. To be a true servant of God you cannot have personal desires mixed in your heart.

It is at junctures like these that one suspects an ulterior religious motive behind the novel, which would also explain the banality of the dialogue. Nobody – not even a murderer – speaks in a convincing voice. Everything – racial bigotry, lust, Christian devotion, horses, cooking – is sanitized for our protection. One looks in vain for provocation, challenge, stimulation.

The lives of forgotten, marginalized persons – among them, people of other ethnicities to our own, and women – are in desperate need of recuperation. Many of those lives are fascinating, enlightening and inspiring, but if we seek deliberately to make them inspiring from our own positions of power and privilege, then we do them a grave disservice and perpetuate the historical imbalances that marginalized them in the first place. Such lives are already inspiring; they don’t need us to make them so. When I compared Deliverance with the short entry on Mary Fields in Wikipedia, I’m afraid I much preferred the latter.

Huzzah Publishing | ISBN 978-0-9978770-0-7 (pbk) | ISBN 987-0-9978770-1-4 (ebook)

#social-sharing-7a696137cec76b2453906ea971e6ca1b{

width: 780px;

}

#social-sharing-7a696137cec76b2453906ea971e6ca1b li{

text-align: center;

}

The post Deliverance | Miantae Metcalf McConnell appeared first on Jack Messenger | Feed the Monkey.

January 18, 2018

Authors: Your Book Reviews Just Got Bigger !

[image error]

Midwest Book Review Feeds the Monkey

My review of You Will Grow Into Them by Malcolm Devlin will appear in the February issue of the Midwest Book Review. Among other things, the Midwest Book Review encourages literacy, library usage and small press publishing, so it’s a thoroughly good thing. Henceforth, I shall send it all my reviews, which will mean additional exposure for books and authors reviewed on Feed the Monkey: I already post to all the usual online retailers, plus Goodreads, Scriggler and Compulsive Reader. My review for You Will Grow Into Them is here. My review policy is here.

#social-sharing-0531c0a2b145eaaf5101eae2d622bd9e{

width: 780px;

}

#social-sharing-0531c0a2b145eaaf5101eae2d622bd9e li{

text-align: center;

}

The post Authors: Your Book Reviews Just Got Bigger ! appeared first on Jack Messenger | Feed the Monkey.

January 16, 2018

Just joined Bloglovin’

The post Just joined Bloglovin’ appeared first on Jack Messenger | Feed the Monkey.