Jack Messenger's Blog, page 10

March 10, 2016

The Fugue | Gint Aras

Published by Tortoise Books

Published by Tortoise Books

While reading Gint Aras’s novel The Fugue the image that came to my mind was not of an eternal golden braid, but of a broken mirror, cracked and fragmented, each tiny slither reflecting a different aspect of a multifaceted narrative. It’s an image of stasis, of everything at once, eternally present, blindingly coeval. And it turns out that this image is not entirely inappropriate, for the novel features mirrors of more or less importance, and characters who inhabit the present and the past simultaneously, and whose lives are splintered beyond endurance and yet who, for the most part, continue to endure.

The Fugue is set in Cicero, a suburb of Chicago, Illinois, but its geographical and emotional roots are elsewhere – in the Ukraine, Lithuania, Russia and Poland, Scandinavia and Mexico – from where many of the town’s inhabitants have departed, often as refugees. Those who have fled the old world have brought their traumas with them, bequeathing them to their children and their children’s children. The novel opens with a primal scene of war, fear and concealment; it concludes with the final, ironic manifestation of that guilt-inducing violence.

The Fugue is thus a novel of paradoxes. Inspired by a notion of the harmonious and contrapuntal progression of musical voices through time, it is equally a story about being stuck in someone else’s nightmare. An epic saga of family lives and losses, it is also a chamber piece with surprisingly few characters. Located squarely in Cicero, its moral implications ripple outwards to cover the entire world. I could not help remembering that faire fugue, in French, means to run away. Some of the characters in the novel have run as far away from themselves as they can possibly get.

‘If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence.’ George Eliot’s astonishing insight, and her attention to the fine-grained textures of daily life, are echoed distantly in Aras’s descriptions of material objects, city streets, and the implications of seemingly innocuous activities such as sharpening a pencil. Yuri Dilienko, perhaps the main character in a novel many of whose personages could lay claim to that distinction, straddles the boundary between the deafening roar of which Eliot writes and its countervailing silence.

Released from a lengthy prison term for murdering his parents, Yuri lives precariously on the impoverished edge of the town’s decaying infrastructure, devoting himself largely to the sculpting of tortured and twisted figures from the scrap metal he scavenges from littered streets and vacant lots. Art, for Yuri, and for the stalled but gifted composer Lars Jorgenson, is a double-edged sword that cuts through to the truth otherwise concealed by the need for forgetting, yet allows anguish and terror to pour out from the ghastly wounds it inflicts.

Yuri may or may not be guilty of parricide (the truth is only partially revealed by novel’s end), but in any event he cannot divest himself of his parents’ presence, for the temporal jump-cuts that incise the storyline ensure that Bronza and Gaja Dilienko remain vividly alive. Indeed, it is this quality of aliveness in all the characters – the Jorgensons, Uncle Benny, Reikel the meat butcher and landlord, Monsignor Kilba and Father Cruz – that constitutes the novel’s principal achievement. It is a rare thing always and everywhere to be totally convinced by the reality of fictional personalities, so it is to the great merit of Gint Aras that he succeeds effortlessly in this respect.

The troubled people whose paths interweave in The Fugue are rarely predictable and seldom consistent. Readers of the novel will find their affections and assessments changing with time and circumstance, so that Gaja, for instance, is at one moment angel, the next demon. Having just seen the excellent film Spotlight, I feared the worst of Kilba and Cruz, who seemed all set up to be monsters, but my expectations were confounded and they, too, develop in interesting ways, while their domestic arrangements and private behaviour are described with documentary-like precision.

Yet it is here that problems might arise for some readers. For me, the novel’s delight in the minutiae of quotidian life – its power to immerse us therein – is both its glory and its Achilles’ heel. As details accrue, as scene follows scene, always intersected by the cross-cutting fault lines of various pasts, one begins to wish for a little more forward momentum, an obvious sign of progression, the unconditional gift of a few significant events. The Fugue has apparently reminded other readers of Tolstoy’s family sagas – a comparison which is unfair both to Mr Aras and Count Leo, whose work never approaches a similar state of suspended animation. To my mind, The Fugue is too long, with too many scenes doing essentially the same thing, too many meetings where issues are left frustratingly unresolved. Once a reader becomes aware of a novel’s coyness in this regard, there is a danger that it becomes alienating or – what is worse – unintentionally amusing. In any case, one must begin to wonder if ultimate revelation can possibly survive such a build-up.

In addition, the structure of a musical fugue is of course meant to be grasped in its entirety in uninterrupted performance. The circumstances of its reception form one of the ways in which music differs from literature: in theory (if not always in practice) we experience music from start to finish in one sitting, while with literature we must be prepared for many interruptions and intermissions, perhaps over weeks. Thus, for me at least, any sense of the fugue as a whole – as a pattern, as an overarching design, as James’s ‘figure in the carpet’ – becomes hopelessly lost and irredeemable.

In my opinion, these are significant flaws in an otherwise accomplished novel that is only occasionally marred by uneven writing. Aras’s prose is unfussy and down to earth, and refreshingly free of pretentions. It does the job intended for it and it does it well. To its great credit, it helps create a world in which the reader is willing to believe. The author brings to bear immense intelligence and sensitivity, and a refreshing disregard for conventional forms. The Fugue truly is literary fiction concerned with the why of narrative and not the what of plot. It cares about people and what they do to one another. Despite my reservations, I believe this is a novel that should be read and probably re-read. That is a sign of literature at its best.

March 7, 2016

Lisa Rüll | Addicted to Peggy

This post has been published to mark International Women’s Day (8 March) and to introduce Lisa Rüll, PhD. A while ago, in Nottingham, Lisa gave a brilliant introduction to the documentary film Peggy Guggenheim: Art Addict. We spoke some while after the show. This is an abbreviated transcription of a longer conversation (the recording itself can be be listened to below). I’ve made many changes here and there for clarity.

Lisa, what first drew you to undertaking a PhD about Peggy Guggenheim?

I was loaned a copy of the 1960 version of Peggy Guggenheim’s autobiography, which was revised from the earlier 1946 version. And I just thought: ‘This is great! She’s completely crazy and very gossipy.’ All the names are there … So that became a starting point of a long, long hobby-horse from 1994 onwards … I did some work on her when I did my Masters … And my tutor on the course asked, ‘What do you want to do for the dissertation?’ And I replied, ‘I think I’m too fascinated with Peggy to do her justice in an MA dissertation. I think I’d like to do my PhD on her.’ It was a long route but I still remain absolutely fascinated.

Judging by what you’ve just said and what you told us at the screening, part of the problem with studying her is her own pronouncements about herself, which seem mutually contradictory and full of myth and confusion and debate – and her activities. Can you arrive at any firm conclusions about her personality and achievements?

I think my instinct was what an odd person she is! And what helped my thoughts was the fact that as part of the MA we did look at the problems of biography and autobiography, particularly around women involved in the visual arts world, where I think there are particular problems and tropes as to how women are meant to be, how they’re meant to be behaving, how they’re meant to write about themselves, how they’re meant to be taken seriously or not. And that tends to shape attitudes, as well as self-representation. So in some respects it’s a real issue.

One of the core problems around Peggy is that she’s not a producer – she doesn’t make a product. She has the galleries and is involved in the selection process, but other people are as well, so there’s an element of collaboration; she’s not writing introductions in gallery booklets for exhibitions, so she’s not doing the writing and research side of things; she’s not making art herself … so she’s more of an agent for other people doing things, rather than someone who is directly producing herself, and that tends to make her quite unusual and easy to dismiss in a way.

Usually, collectors, patrons, philanthropists, gallerists are able to have another producer string to their bow that helps them be taken seriously. She doesn’t have that; she’s purely an agent: she gets people in contact with each other; she acts as a catalyst for relationships and connections, but she isn’t a producer. That makes her quite problematic because the way she writes about herself makes it a case of ‘What’s my purpose?’ I think that’s why she is so full of self-doubt: ‘I need to be taken seriously, but I’m going to undercut myself at the same time. I really regret that I gave lots of things away’ – but that meant that her name is in all sorts of galleries and collections acoss the world and is part of the reason why the name is still visible. So she doesn’t fit with standard behaviours of male versions of that and she doesn’t fit particulary well with the female versions because she’s not this creating person. She’s self-fashioning … it’s an act of production, but it’s not one that’s generally taken seriously … She’s very glamorous but she’s not very attractive. She over-the-tops to compensate.

Judging by the film we saw, there’s so much shocking sexism and snobbery about that.

That’s partly why I find her so fascinating: she highlights some of those sexist attitudes and expectations because they almost provide the excuse for not being able to take her seriously because she doesn’t produce in the same way and she isn’t doing the same thing as them. Actually, collecting the sorts of things she was and presenting them in galleries wasn’t the norm for anybody at the time, and least of all for a woman. So there are all sorts of ways in which she could be dismissed – and then to add in the fact she had a relationship with so-and-so ‘and so we can’t possibly take into consideration they were actually any good as an artist …’ Well, actually, we can! All the other people have leapt on board now, but Peggy was there first!

So she was really quite key, but the snobbery and the sexism are quite shocking – the old-fashioned ideas of connoisseurship that she challenges because she mixes the roles: collectors have their collections in their private places or they make a public donation to something else; you didn’t set up your own gallery where you might sell stuff; you might buy stuff if there were things left over if you didn’t want your artists to go home empty handed. But Peggy breaks all the rules and expectations and that’s where snobbery and sexism can really take hold …

Let’s talk about your writing now. As a female academic yourself, how important is writing – being an author – to you personally and to your career?

I don’t conventionally fit expectations – all these things that keep connecting me to Peggy! I’m not a subject academic lecturer, I work mostly as a studies strategy teacher with students with mental health issues and specific learning difficulties … I like writing … and I hate writing! … I don’t think writing is easy for a lot of people. I certainly have never found it easy. But do I like doing it? Yes, I like having done it, but that’s not quite the same as liking doing it. It’s important to me that I still do writing in some form or another because it keeps those skills honed, in practice. I like doing things like talks and conferences because I write it to be heard … I don’t write things that are meant to be heard as if I were writing to be read on the page. There are different things about the audience …. It’s important that I gauge what the audience is that I’m communicating to. I script it with every pause and every line because then I know exactly how long it’s going to take and not be given a ten-minute slot and speak for forty-five minutes.

I’m a writer of fiction, while you’re a writer of academic non-fiction, and also an accomplished speaker, so I imagine we’re approaching the subject of publication and audience from different perspectives. In your view, what are the similarities and differences between the two?

I think once you’ve got your head round who you’re writing for then the format and style become less of an issue. Then the experience of writing is much more about the individual person. So part of the reason why I work quite well with students who experience perfectionism and procrastination is ‘Hey! Been there! Done that! …’ It means I’ve learnt an awful lot about the strategies to get around that and overcome the sensations of the paralysed moments over the keyboard … and rethink and come back to it. So I talk a lot to my students about being virtuous but not effective … I think a lot of writers struggle with that by ending up being very virtuous and doing stuff, but not necessarily getting closer to where [they] wanted or needed to be …

Again it comes back to purpose, thinking about your audience and the nature of the writing you are trying to do and who it’s for. I think that can be valuable to unpick … so I don’t go too far off at a tangent … not stopping myself doing incredibly interesting things like reading, but maybe having a reading journal and make a note of all the details, how to find it, why I thought it was interesting, and I’ll come back to that notebook at a point where it’s not distracting me …

I’ve always tried to keep my hand in with lots of different sorts of writing. If I can work out who the audience is, what it’s for, what proportions it needs to have – then that gives me a shape to work within so that the distractions and misdirections are perhaps more easy to manage.

Academia is more and more adapting itself to market imperatives and is called upon increasingly to justify itself in terms of its usefulness and economic benefit. What is your opinion about this? Have academic independence and integrity been compromised?

I’m very bad at playing politic! … I’ve been around this university for about sixteen years on both sides of the desk … so I’ve seen how much it’s changed … It is more market driven. How does that relate to education and the quality of writing? It’s problematic. I’ve always been quite open about the fact that I appreciate it’s not necessarily a good thing for either a student or an institution that somebody takes thirty-five years to write a PhD in a way that, historically, it was potentially possible … Equally, I think that what is produced is now much more a product to meet a particular requirement. It’s responding to audience on one level, it’s responding to criteria on one level, but does it mean you always get the best research or do you get the research that can be done in three to four years within these frames?

I think there is increasingly less space within academia for the big projects, the things where you might not know an answer within the next ten years … Some research might potentially take a generation. If you can’t come up with measurable impact assessments and so on … does that mean it’s not worth doing? Not necessarily. We’ve changed what PhD research and academic writing is. I’m not saying that it is necessarily always worse, but there are certain things it no longer does. People who I knew who were quite established academics when I started, and who are now emeritus professors, would not necessarily have been able to have the time and space to do the sort of research projects that needed a lot of thinking time – a lifetime’s worth of observation and doing ideas over, thinking about philosophical thoughts and changes over time. I don’t think there’s the same space for that sort of thinking as there once was. That feels limiting …

And you have the very obvious marketization thing, which is ‘Where’s my 2.1?’ … No! Despite recent language to the contrary, you’re actually not a customer buying something, you are accessing the opportunity to learn from it. To use a lovely analogy: it’s no good just having a gym membership, you actually have to use it. So it’s no good just getting a place at university, you have to do something with it; you have to stretch your brain; you have to do the reading and research; you have to engage with the support and the advice. And then you probably will do better than you might have done without that. But there is no guarantee! …

Marketization is not as straightforward as ‘people will be put off!’ They’re not necessarily put off. I think the level of investment and expectation they have of it of providing the appropriate outcome has probably ramped up. And by far the impact of students managing the level of stress to deal with that expectation is always growing … Mental health issues are on the increase in education at all levels and that’s disconcerting … in the broader context [students’] capacity to manage that is harder for them.

We may be entering a new geological epoch – the Anthropocene – in which, for the first time, humankind must contemplate its own extinction as a direct result of its own activities, a process that has already begun and which could be completed very quickly indeed. What are your thoughts on this? If you could save from destruction one single book and one other work of art, what would they be?

Given my fascination with Surrealism and given my interest in exploring somebody who resolutely collected modern art, I have to say that one of the works I would probably want to save would be resolutely not that. I have a ridiculously burning love for a painting of Ophelia by J. W. Waterhouse … There are innumerable depictions of Ophelia … but … why I particularly like that version is because it’s the only one where I felt that it captured something of the loss of sanity in her expression.

Ophelia by J. W. Waterhouse (third version, 1910)

[Ophelia has] a beautiful blue dress; she’s got beautiful flowers around her; there’s people in the background on a bridge; and she’s running towards the water and her expression is somewhere between blank and horrified – almost a sense of ‘I’m aware that I’m not in full control of my capacities any more, but I don’t know what else to do’ – in the context of the death of her father, the abandonment with Hamlet being sent away. It’s still one of the pictures I come back to. I love it. I don’t know why I still have a real passion for it.

If not that painting, I would love the beautiful portrait of Peggy that is the Man Ray picture of her from when she was in her early twenties … which I have in various versions all over my house … Peggy’s my wonderful figure of agency and the Ophelia figure … I love Hamlet! It’s an amazing text. It’s always rewarding to come back to and because it links the visual and the written I think that’s one of the reasons why I still love that particularly.

So might Hamlet be the text you’d want to save?

I think it probably would – because it’s something I can endlessly go back to with all the different stage versions that I’ve seen in my head and the different intonations of the lines and the different emphasis that’s given to things. It’s such an endlessly rewarding text but particularly as something that is performed – because, again, it’s the fact that it’s not just one thing , it’s the fact that it links to other things, so it’s a written text but the only way really to appreciate it is to see or hear it being dramatized, being acted, people being involved in performing it. So, again, it’s that cross-over between the two.

It seems to run through your life and studies!

Indeed!

I think you’ve made a marvellous choice. You’re a woman after my own heart!

Thank you very much! It’s been a pleasure! I’ve really enjoyed the conversation.

I’ve enjoyed listening to your views! Thank you!

http://jackmessenger.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/20160211-154003-0001.mp3

Lisa Rüll was born and initially educated in Nottingham, UK. Following three years of Open University study alongside her work at a local accountancy firm, she moved to the West Midlands in the early 1990s. She completed her first class honours degree in History of Art and Design and Women’s Studies at the University of Wolverhampton and subsequently taught at the university and other HE and FE institutions in the Midlands and Yorkshire. She also worked for a year at Wolverhampton Art Gallery and Museum co-organizing a number of exhibitions before completing a part-time Masters in Feminist History, Theory and Criticism in the Visual Arts at the University of Leeds (Distinction). In 2000 she started part-time a PhD in the School of American and Canadian Studies, University of Nottingham on Peggy Guggenheim (which she finished with full-time AHRB funding). Lisa was one of the 100 Heroes nominated by students to mark a hundred years of the University of Nottingham Student Union.

March 3, 2016

Copyediting for Indie Authors | Launch Day 20 March

Available exclusively as an ebook only on Amazon, Copyediting for Indie Authors is FREE for the first three days.

Find out what basic errors put off readers and reviewers (you’ll be surprised).

• Save time and money.

• Link to two more free tips, plus handy copyediting checklist.

• Lift your book closer to perfection.

March 1, 2016

Another Masterpiece Bites the Dust

Have you noticed how most of the novels you read are masterpieces that will stay with you the rest of your life? Have you been mesmerized and dazzled by books that are devastatingly atmospheric, compulsive and irresistible? Seduced by the style and elegance of quick-paced, taut prose? Bewitched by tense and enigmatic storytelling? Tantalized by mystery and suspense?

I have. Or, rather, I should have been, for these are the judgements of respected newspapers and magazines on – well, just about anything, including the last book I read. Somewhat underwhelmed by the book in question, I began to wonder why I felt a frisson of déjà vu as I gazed misty eyed across the critical chasm that isolated me – a humble reader – from these cloud-capped towers of hyperbole. Was there something wrong with me? Had I lost my appreciation for great literature? Had I become jaded, unresponsive, emotionally ossified?

Now, let me say right away that the book in question is fine in many ways and brilliantly translated (inasmuch as it’s impossible to tell it has been translated). However, for me, it was as if the author had merely thought deeply about life without ever having lived it. He was great on theory, and could describe the gradations of emotion in exquisite detail, yet gave not the slightest inkling he had ever experienced these things for himself (of course, I speak of the writer, not the man). It was as if Immanuel Kant, in a fit of misguided artistic ambition, had rewritten his Critique of Pure Reason as a romantic novella. As the story limped wearily along the tedious path to its foregone conclusion, dragging me behind as the unwilling auditor to its interminable disquisitions about nothing in particular, I recalled the book I had read previously, which was also described as an extraordinary fictional achievement and one of the finest novels of all time. That had also turned out to be a clunker.

Now, let me say right away that the book in question is fine in many ways and brilliantly translated (inasmuch as it’s impossible to tell it has been translated). However, for me, it was as if the author had merely thought deeply about life without ever having lived it. He was great on theory, and could describe the gradations of emotion in exquisite detail, yet gave not the slightest inkling he had ever experienced these things for himself (of course, I speak of the writer, not the man). It was as if Immanuel Kant, in a fit of misguided artistic ambition, had rewritten his Critique of Pure Reason as a romantic novella. As the story limped wearily along the tedious path to its foregone conclusion, dragging me behind as the unwilling auditor to its interminable disquisitions about nothing in particular, I recalled the book I had read previously, which was also described as an extraordinary fictional achievement and one of the finest novels of all time. That had also turned out to be a clunker.

The trailers for films made in the Golden Age of Hollywood describe their wares in apocalyptic terms: as searing melodramas and unforgettable experiences of Earth-shattering significance. They drip with hyphenated superlatives and bizarre metaphors involving scorching, burning and blazing (the old film stock was highly flammable). It’s amusing, but that is what one would expect from publicists working in a factory that churns out genre productions. How has this mentality infiltrated the dispassionate appraisal of fiction?

As ordinary readers, we would hope for some reliable guidance from reviewers. When every book is a masterpiece, none are. We are not well served by this consensual rush to praise. It must be hard for dissenting voices to make themselves heard. When everyone is of a particular opinion, then the natural inclination is to believe that one is wrong to think otherwise, that perhaps one has missed something that everyone else has ‘got’, that one’s critical faculties are not as sharp and precise as they should be.

There’s probably nothing fundamentally new in all this, but it does seem to have reached the acme of absurdity. Readers, let’s tread warily and let no one lead us by the nose. If there is any searing and scorching to be done, it shouldn’t be allowed to burn a hole in our pocket.

Copyediting for Indie Authors | Cover Reveal

Here it is! And I can hardly contain my excitement! What started off as an idle thought, grew into a side-project, then developed into a fully fledged obsession, will soon become a reality. Launch day is fast approaching. Aaargh!

Here it is! And I can hardly contain my excitement! What started off as an idle thought, grew into a side-project, then developed into a fully fledged obsession, will soon become a reality. Launch day is fast approaching. Aaargh!

I’ve spent my career in the publishing industry as a writer, copyeditor and editorial project manager, submissions reader and reviewer. I’ve worked for major trade and academic publishers such as Berlitz, Routledge and Wiley-Blackwell, plus major international organizations in the not-for-profit sector. I’ve helped literally thousands of authors on many thousands of books – books of all kinds, from travel guides to children’s picture books to cutting-edge academic scholarship.

The ten top tips in Copyediting for Indie Authors are among those I’ve used in my professional career to make thousands of books the best they can be. The difference is that instead of spending a lot of money on copyeditors who may not be right for your book, you can do these things yourself, right now, for free.

Over the past six months or so, I have had to refuse a great many requests for book reviews for one reason or another. Sometimes the book is not the sort of book I like to review; sometimes I don’t feel qualified to review a particular book.

However, the main reason I’ve found myself saying no to reviews is because the published book is not in good shape and contains lots of avoidable errors. I’ve written this short guide to provide some basic tips for improving the editorial presentation of books. It addresses some of the simple problems that put off potential readers and reviewers. In my experience, I know that if I see one or two of these errors on the opening page of a book, I simply won’t review it. I’ve copyedited hundreds of books in my time, so I suppose I have come to recognize many of the danger signs.

Copyediting for Indie Authors includes a link to two more free tips, plus a handy copyediting checklist. It will be available as an ebook only on Amazon.

Now we’re good to go!

February 29, 2016

Copyediting for Indie Authors | Launch Day 20 March

Available exclusively as an ebook only on Amazon, Copyediting for Indie Authors is FREE for the first three days.

Find out what basic errors put off readers and reviewers (you’ll be surprised).

Save time and money.

Link to two more free tips, plus handy copyediting checklist.

Lift your book closer to perfection.

February 25, 2016

Copyediting for Indie Authors

LAUNCH DAY 20 MARCH

I occasionally write book reviews for my blog over at Feed the Monkey and elsewhere. Over the past six months or so, I have had to refuse a great many requests for reviews for one reason or another.

The main reason I’ve found myself saying no to reviews is because the published book is not in good shape and contains lots of glaring errors. This is sad, as a great deal of good work is disappearing forever simply because of bad copyediting. From the title on the cover of a book to the last sentence on the final page, good copyediting establishes

• Authority

• Credibility

• Professionalism

• Trust

These are things we need to provide readers right from the start, otherwise they will give up on our book. Look at it from their perspective: at the very least, they need to invest their time and probably their money to find what they’re looking for. If they don’t find it in our book, they’ll look elsewhere.

I’ve written a short guide to some basic tips for improving the editorial presentation of books. It’s called Copyediting for Indie Authors and it addresses some of the simple problems that put off potential readers and reviewers.

I’ve spent a lifetime in the publishing industry as a writer, copyeditor and editorial project manager, submissions readers and reviewer. I’ve worked for major trade and academic publishers such as Berlitz, Routledge and Wiley-Blackwell, plus major international organizations in the not-for-profit sector. I’ve helped literally thousands of authors on many thousands of books – books of all kinds, from travel guides to children’s picture books to cutting-edge academic scholarship.

The ten top tips in Copyediting for Indie Authors are among those I have used in my professional career to make thousands of books the best they can be. The difference is that instead of spending a lot of money on copyeditors who may not be right for your book, you can do these things yourself, right now, for free.

Copyediting for Indie Authors will be published on 20 March as an ebook only on Amazon. By way of a thank you for reading it, readers can link for free to two more essential top tips, plus a useful copyediting checklist.

What the reviewers are saying:

‘Indispensable! Oh how I wish I had these ten tips when I was copyediting and formatting my novel. Trust me, I’m going to keep this slender document with my dictionary and thesaurus right next to my computer.’ Ginger Bensman, author of To Swim Beneath the Earth

‘I wholeheartedly recommend Jack and Brigitte Messenger’s how-to guide, Copyediting for Indie Authors. Just follow their excellent tips for a more professional-looking book.’ Mark Gordon, author of The Snail’s Castle

‘I have no hesitation in recommending this accessible and engaging guide to all independent writers. Laying out their advice in forthright, unambiguous yet never hectoring or patronising terms, and supporting each of their ten top tips with clear examples, the authors admirably synthesize lessons learned from their years of experience as publishers, freelances providing expert services to publishers, and authors themselves. This guide is just what writers will have been waiting for!’ Ally Dunnett, formerly Production Director for Social Sciences and Humanities Books, John Wiley & Sons

‘This is an excellent guide for authors striving to eliminate copyediting errors that can sink a book from the start. Clear and concise, it provides many concrete examples of how to do it right.’ Ulla Jordan, author of Lost Ground

‘Professional copyediting is vital for any indie author who wishes to compete with traditionally published books. In this quick-reference guide, Jack Messenger provides a valuable resource that will enable authors to correct issues from punctuation and paragraph breaks to common spelling errors. Highly recommended!’ Ken Doyle, author of Bombay Bhel and Gateway of India

‘As a professional reviewer, I often come across books (and queries) that are poorly copyedited. This not only indicates that the author hasn’t valued their work enough to take care, but poor copyediting can impinge dramatically on a book’s clarity and readability. As an author, I know what it’s like to be professionally copyedited, and I also know how hard it is to DIY. Jack Messenger’s easy to read and succinct set of top ten tips is not a substitute for a pro, but it’s an excellent way to avoid the most common errors and lift your work above the vast majority of books being published today. Use this guide consistently and your work will most certainly benefit.’ Magdalena Ball, Compulsivereader.com

February 23, 2016

Are You a Dinosaur? | Find Out Here

Cast your mind back sixty-five million years.

Most of the dinosaurs were going about their daily lives – hanging out at the beach, shopping on their dPads, meeting friends for drinks and a barbecue. A group of stegosauri played tennis all that summer; T. Rex performed to packed houses twice nightly; there was a general mood of optimism among the brontosauri (they were tall and thought they could see further than anyone else). For some, material prosperity had never been greater: luxury pads; fast cars; trophy spouses. For others, working in the sweatshops and living in the slums fenced off from Jurassic Playland, life was nasty, brutish and short.

Did you see that?

The dinosaurs had no natural enemies (except, of course, each other). They had conquered the world millions of years before and remained its undisputed rulers. There was nothing to make anyone believe this would ever change. Some intellectual types bemoaned the hedonism and frivolity of dinosaur society – ‘Live now, pay later, Diners Club …’ – but ignorance is bliss, and all most reptiles wanted was to enjoy themselves.

Then a strange, bright object appeared in the sky. Few of the dinosaurs looked up and wondered what it was. Yet soon after it hit the Gulf of Mexico, there were no more dinosaurs left alive. A whole civilization was wiped out, including fast food restaurants. The mammals who witnessed this phenomenon called it the Fifth Great Extinction.

We human beings, of course, are entirely dissimilar to dinosaurs. We have greater reasoning powers. We can think of the future, foresee problems and take avoiding action. When trouble looms, we do something about it. Don’t we?

Here’s what we know:

The previous four Great Extinctions were caused by climate change, ice ages, volcanoes – a familiar roll call.

Currently, the Earth’s species extinction rate is anywhere from one hundred to one thousand times higher than normal – and that’s only the animals we know about.

Three quarters of animal species could be extinct within several human lifetimes.

We only have ourselves to blame: monocultural agriculture, habitat destruction, pollution – the great human technosphere.

Nobody knows whether or not humanity can survive this rate of loss. And that’s not taking into account all the other consequences of climate change. Some of these consequences tip over pretty fast once they get going. And they have got going.

Scientists are already beginning to talk about the Sixth Great Extinction. Some believe it to be well underway. For many human beings, normal life is pretty ugly. The coming years will see that ugliness spread like a dark stain across our bright glittering world.

It is highly possible that it is too late to do anything about all this. But if we are finally to rouse ourselves, hadn’t we better hurry just like anything?

Does humanity deserve to survive? Are you a dinosaur or a human being?

Going out like a dinosaur.

February 17, 2016

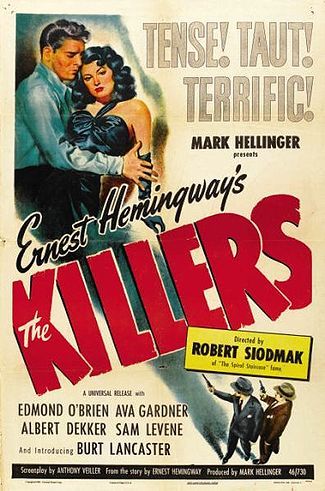

Ernest Hemingway | The Killers Keeps On Killing

‘The door of Henry’s lunchroom opened and two men came in …’

And, we might add, immediately barged their way into the cultural history of the twentieth century. Three thousand words later, Ernest Hemingway’s seminal short story The Killers watches in relief as the two men disappear from the narrative, still intent on killing Ole Andreson, ‘the Swede’, ‘just to oblige a friend’.

In considering the afterlife of stories and how successive versions and adaptations interpret the original for their own times, it can come as a shock to realize just how old The Killers is: it was written in 1927. Yet this tale which appears so closely tied to its particular milieu is extraordinarily amenable to reinterpretation and variation. The Killers is firmly embedded in the small-town America of the mid-1920s, yet it is that very specificity which has rendered it malleable and pertinent to generations of artists.

The Killers in 1927

The incantatory prose of Hemingway’s original short story, with its careful repetitions and juxtapositions of words and phrases, is highly artificial, its stripped-down modernism the equivalent of existential threat: there are no words to hide behind, no euphemisms in which to dress things up, no distractions from the reality of death that’s a hair-trigger away. Yet the rhythms of the dialogue in which the story is almost entirely told are also disturbingly naturalistic: it’s as if all the characters – Al and Max, George the waiter, Nick the diner and Sam the cook (recipient of repeated racial slurs) – are quoting themselves, knowingly freighting the banal linguistic currency of their everyday lives with the significations and connotations beloved of literary fiction.

Al and Max are effortlessly nasty pieces of work: they imbue every trivial remark with the potential for violence. When they start ordering people about, nobody argues, despite the fact that neither of them produces a gun – these men do not need to exhibit their firearms because their language and behaviour are already sufficiently intimidating. Early on in the story, George’s forgetfulness about their dinner orders could, it seems, so easily cost him his life. Al and Max convey total menace because the outcomes of each micro-social interaction depend on their moods; they know that, they know we know that, and we all know that Al and Max can choose to act on those moods if they so wish. What’s worse, they are not slaves to their own feelings; rather, they are in complete control of them, yet morally disinterested as to whether or not they indulge them.

Al and Max overshadow the narrative, yet their intended target, Ole Andreson, is equally important as a character, for it is his passive acceptance of his death, his affectless resignation to a future that is anticipated but withheld from the reader, that suggest Al and Max are truly inescapable. Ole’s failure to implicate himself in the events he foresees amounts to an emotional exhaustion, the causes of which are not explained. Ole admits ‘I got in wrong’ with somebody, but he can’t make up his mind to leave his room. ‘I’m through with all that running around,’ he tells Nick, who can’t stand to think about Ole waiting ‘and knowing he’s going to get it. It’s too damned awful.’ ‘Well,’ George tells him in the last line of the story, ‘you better not think about it.’

The Killers Goes to the Movies

The dialogue form of The Killers – especially its blend of everyday subject matter with murderous intent – perhaps explains why the story has been so influential on the movies. We can trace its influence on such key films as The Public Enemy (dir. William Wellman, 1931) and Little Caesar (dir. Mervyn LeRoy, 1931), on White Heat (dir. Raoul Walsh, 1949) and Goodfellas (dir. Martin Scorsese, 1990), on Reservoir Dogs (dir. Quentin Tarantino, 1992) and Pulp Fiction (dir. Quentin Tarantino, 1994).

For me, however, three of the most interesting cinematic incarnations of Hemingway’s short story are The Killers (dir. Robert Siodmak, 1946), Ubiytsy (The Killers) (dir. Andrei Tarkovsky, Marika Beiku and Aleksandr Gordon, 1956) and The Killers (dir. Don Siegel, 1964).

The Killers in 1946

Twenty years have passed since Hemingway’s story was first published in Scribner’s Magazine, and the world is now infused with the kind of postwar angst and moral complexity indexed by the noir cinematography of Woody Bredell. Character actors Charles McGraw and William Conrad (top photo) play the eponymous killers to perfection: every line, every word, is made arrestingly funny or frightening (often, funny and frightening). In addition, Burt Lancaster (as Ole Andreson) delivers his lines with weary resignation to his fate: from the cadence of his voice alone, we realize there is no escape.

Twenty years have passed since Hemingway’s story was first published in Scribner’s Magazine, and the world is now infused with the kind of postwar angst and moral complexity indexed by the noir cinematography of Woody Bredell. Character actors Charles McGraw and William Conrad (top photo) play the eponymous killers to perfection: every line, every word, is made arrestingly funny or frightening (often, funny and frightening). In addition, Burt Lancaster (as Ole Andreson) delivers his lines with weary resignation to his fate: from the cadence of his voice alone, we realize there is no escape.

Siodmak’s film noir wisely retains most of Hemingway’s dialogue for its opening scene in the diner. Two decades of social change do not appear to have affected the clarity and meaning of Hemingway’s words, which gain in richness and power from the nuanced performances of the actors who utter them. Film is a collaborative medium of directors and producers, writers and actors, photographers, composers and craft workers. In this case, they had to come up with another hour or so of story explaining what happened to bring the killers in search of Ole. It’s excellent, but nothing can quite match the opening scenes.

The Killers in 1956

It’s quite a jump from the overtight overcoats and derby hats of Hemingway’s killers in 1927 to the looser clothes and fedoras of Siodmak’s film of 1946, but how about a student film made in the Soviet Union in 1956 that transposes Henry’s lunchroom to mid-century Moscow?

Tarkovsky et al.’s nineteen-minute feature Ubiytsy manages to suggest that Al and Max are agents of the government, their dark coats and bland faces part of the trademark anonymity of KGB operatives with a job to do in the dead of night. Assassination has become the business of the totalitarian state apparatus, from which nobody is safe. As if to underline the point, a customer in the diner whistles Lullaby of Broadway, regarded at the time as a song about freedom.

Listening to the Russian dialogue in this politically charged milieu, one can begin to see the connections between Hemingway’s prose and the kinds of literary experimentalism that came after him. Harold Pinter, for example, gave to his characters the kinds of obsessive fascination with words and their meaning that stem from The Killers, usually with a political charge similar to that which lies beneath the surface of Ubiytsy.

The Killers in 1964

Don Siegel’s 1964 film (originally made for television but deemed too violent and released for cinema exhibition instead) eschews the noir aesthetic for the bright glare of daylight, dazzling colour and alienating back projection. This is akin to the unreal reality of the Zapruder footage.

Don Siegel’s 1964 film (originally made for television but deemed too violent and released for cinema exhibition instead) eschews the noir aesthetic for the bright glare of daylight, dazzling colour and alienating back projection. This is akin to the unreal reality of the Zapruder footage.

Here, Hemingway’s story is jettisoned entirely, save for the puzzle of the pursued man’s reluctance to flee. The two killers (played by Lee Marvin and Clu Gulager) look like publicity-shy business executives, their briefcases filled not with papers but handguns and silencers. We are in the world of corporate America and organized crime, and these are two of its most dangerous functionaries, to whom nothing is sacred. One recalls the terrible coincidence that JFK was assassinated while this film was shooting. In addition, its own Mr Big – gunned down by Lee Marvin’s hit man – was played by future US President Ronald Reagan.

The Killers Forever

The buttoned-down iconography of Hemingway’s original story lives on in countless novels, films and TV shows, while his dialogue continues to inspire writers today (including, occasionally, Jack Messenger). The influence of The Killers does not look as if it will be diminishing any time soon. Is this a good thing, or is it stultifying and restrictive?

Doubtless there have and will be many instances where inspiration degenerates into second-rate imitation, but great books and films have a knack of finding nourishment from the example of The Killers, within whose shadows succeeding generations have found a light for their own times. ‘You ought to go to the movies more,’ Max advises George. I can’t find a flaw in that argument.

February 10, 2016

Raking the Dust | John Biscello

Published by Zharmae Press

Published by Zharmae Press

Recently, I mentioned to an author that writing can sometimes seem a trivial and frivolous occupation. She replied that she never thought of it that way. It made me wonder if insecurity about writing is more of a male problem than a female one. Rather like male film actors who indulge in ‘manly’ excesses to compensate for their lack of self-esteem, there are male writers who embrace a lifestyle based on alcohol or drugs or sex or danger and any combination thereof in order, it seems, to bolster something within themselves that whispers in the night that making up stories is unworthy of real men.

Alex Fillameno, writer and central character in John Biscello’s Raking the Dust, appears at first sight to be just such a man. He dwells in bars with his friends, drinks prodigious quantities of alcohol, takes drugs when they’re offered and borrows money when necessary. His working life – such as it is – comprises stints as Spider Man at a toy shop in Taos, New Mexico, and waiting tables. Between times he looks for a job in a half-hearted manner, unsure of what he wants and where to find it.

Alex paraphrases hard-drinking Raymond Chandler (‘Alex, I repeated in my mind, as if trying the name on for size to see if it fit’) and frequently references Hemingway, Kerouac, Miller and Saroyan. He possesses an alter ego, Lex, who is prone to irritability, violent outbursts and exhibitionism. He also has an ex-wife, with whom he has a young daughter, and is haunted by memories of 9/11 – not so much the event itself as the coincidental death of his girlfriend on that date, nightmares about which continue to disturb him: ‘I stand there, voiceless and time-locked, the future dying inside me.’

Existential angst and moral dislocation have been compounded by his move from New York to Taos, where he has come to get away from his pain, only to find it waiting for him. Raking the Dust is strong on the sense of drift that people such as Alex and his friends exhibit, all of whom are occupied in one way or another with life’s complications: economic survival, mental and physical illness, family breakup. The novel does more than hint that such difficulties have become a national malaise.

Reality is a complex, elusive, untrustworthy construct in Raking the Dust. Alex has experiences that we must take as real even though many of them are impossible. Is his mind a reliable guide, soaked as it is in alcohol, narcotics and a writerly self-reflexiveness? Or does the world quite literally comprise a seemingly endless series of alternative frameworks for perceiving reality? Paradoxically for a prose writer, Alex has loops of film that play in his head over and again, condemning him to review the past and to distort it as well. These images are partly self-generated, partly imposed by a surrounding culture whose primary components are signifiers devoid of signifieds.

Are we reading Alex’s own novel? It’s hard to say, as we don’t know a great deal about his writing, or whether we should believe him when he claims to have finished his collection of New York stories. It’s here, most of all, that we encounter the brotherly binary of torment and talent – the romantic myth of the hard-living male author whose art is inspired rather than ruined by semi-permanent intoxication. This has surely tipped over into cliché by now, and I remain uncertain if Alex’s wit and repartee enable him to emerge totally unscathed from this stereotype.

John Biscello dispenses with quotation marks around dialogue, and adopts instead an unemphatic style in which speech floats in on fresh lines that could just as well be generated by Alex himself. Apart from the odd awkward omission of question marks, for example, this works well, although occasionally I had to re-read a line when I misinterpreted its status. However, for me, the writing sometimes becomes perfunctory late on in the novel, when Alex moves to San Francisco, by which stage I was left with little energy for fresh locations and new characters, and it seemed as if the author felt the same.

The press release for Raking the Dust describes it as full of sound and fury, which is unfortunate, as it sets up the question as to whether or not the novel is busy signifying nothing. I was reminded in this respect of the films of Paul Thomas Anderson, whose recent forays into the epic and emblematic have contained at their superbly wrought, coldly crystalline heart – emptiness. Try as one might, there is simply nothing there to grasp.

Some readers may think the same about this novel. Much will depend on their willingness to go along for the ride with Alex, whose solipsistic life is inevitably replete with repetitions and inconsequentialities that are not intrinsically fascinating. One drunken episode is much like any other for an outsider, and I could have done with fewer cute conversations with Alex’s daughter. Indeed, it often seemed to me that I was obliged to listen in on family interactions about which no one except their participants could care, or that I was reading an enormously long short story rather than a novel. In that respect, some bold and judicious eliminations would have increased the story’s forward momentum.

John Biscello is clearly an immensely gifted writer who has attempted something in Raking the Dust that will certainly win it admirers. I admire much of it myself, yet I find I cannot warm to it. The trade-off between life and literature often involves some strenuous negotiations, the outcomes of which are not always what we would wish. Raking the Dust describes an extreme case, and our appreciation of the novel will depend on our responses to Alex and his problems. I really do hope he finished those short stories.