Juha I. Uitto's Blog, page 13

June 20, 2011

Music for Lights @ Baruch Performing Arts Center, June 12, 2011

It is now three months since the unprecedented earthquake and tsunami ravaged northeastern Japan and, although much of Japan has returned to normal, recovery in the regions directly hit is still far away. Still now more than 90,000 people stay in temporary shelters. Then there is the whole nuclear hazard caused by the meltdown of three reactors in the Fukushima nuclear power plant. The Japanese authorities have clearly been complicit with TEPCO, the company that runs the plant, in playing down the extent of the disaster and it has come to light that the radiation escaped in the accident has been twice the level that was officially reported. All of this has implications to how soon—if ever—the inhabitants from around Fukushima can return home to restart their lives.

Music for Lights was a benefit concert for Japan relief efforts organized by two young Japanese women, Jun Kubo and Hiromi Abe, based in New York. Both are versatile musicians comfortable in a variety of idioms ranging from Western classical to jazz. The concert was held in the beautiful Engelman Recital Hall of the Baruch Performing Arts Center in New York City's Gramercy Park neighborhood.

The two women started the concert with three duets for flute and piano. The first, Sonatine pour Flûte et Piano by Pierre Sancan (1916-2008), was a new acquaintance for me and I was taken by the beauty of the music. Jun Kubo's golden flute sounded lovely in the modern piece. Her tone is very smooth, especially in the lower register. I have earlier heard her in Meg Ogura's Pan Asian Jazz Orchestra and I have to say that her clean flute sounds more convincing in this classical context, rather than the contemporary band. Next Jun Kubo played Kojo no Tsuki, an old Japanese song which belongs to the shakuhachi repertoire. Kubo started the song with another type of bamboo flute, the transverse shinobue, before switching back to the Western flute. The arrangement was impressionistic and the overall performance quite low key. Hiromi Abe stumbled barely noticeably in some of the piano interludes. The ladies' performance ended with Sicilienne et Burlesque by Alfredo Casella (1883-1947), a rather playful piece in three parts, which suited the temperament of the two musicians well.

In between the pieces, Jun Kubo, who left Japan at 10 but keeps close contact there and even speaks the language fluently, told the audience how she had been in a meeting in Tokyo when the earthquake struck. By that time, she had already been five months pregnant. She had initially thought it was one of the "routine" Japanese earthquakes, but realized that this was something different when all the Japanese colleagues rushed screaming under their desks.

The star of the event was Jun Kubo's former teacher, Robert Dick. He has been called by some—and with some justification—the best flute player in the world. Dick is technically superior and enormously creative on flutes of various length. Like his young student, Dick is enormously versatile and at home in many kinds of music. Unlike her, though, he can be quite untamed when the music so requires. This was the third time I had the chance to witness his live performance and every time the setting has been entirely different. Again this evening the music presented a different side of the maestro. Dick briefed the rather conservative looking audience before starting his performance, saying that the best way to listen to his music was, well, just to listen to it: "Don't worry about the flute, that's my job."

Robert Dick began his segment of the concert with his own 1973 composition, Afterlight, an expressionistic exploration of the flute in which he blew two, three, even four tones at the same time, at times creating a rather eerie atmosphere. He then moved on to play the Sonata Appassionata composed by Sigfried Karg-Elert (1877-1933) in 1917, thus establishing his classical music bona fides before returning to his own compositions. What followed was Bells for Diz, a bass flute improvisation dedicated to Dizzy Gillespie who, as Robert Dick remarked, had two different stage personalities: one extremely focused when playing the trumpet and another, bubbling and lively when playing Afro-Caribbean percussion. Bells for Diz was an homage to the latter and the creative composer-performer used the big curved flute to generate an array of percussive sounds using the big keypads and blowing into the flute in various ways. The resulting music was inventive and joyful.

The final piece introduced a Dick invention, the glissando headjoint, which on the flute performs the same function as the whammy bar on an electric guitar. The inventor was initially inspired by Jimi Hendrix' guitar playing to explore how to create similar effects on the flute. He then worked over many years with instrument makers to realize his invention. The piece that concluded his part of the concert was a blues in which Robert Dick stretched the possibilities of the flute. The piece started and ended with slow slide guitar like licks. In between, he demonstrated a resourceful musicality and stunning technique moving from the blues to West African native flute tonalities and back via impressive runs.

Following Robert Dick in a concert is an unthankful position to be in. Therefore it was just as well that the next performer, singer Sahoko Sato, switched gears and genres entirely. The mezzo-soprano sang four songs accompanied by Rikako Asanuma (this young pianist is a native of Iwate, the prefecture in Japan closest to the epicenter of the March earthquake). These included Ave Maria by Pietro Mascagni (1963-1945); Kono Michi, composed by Kousaku Yamada (1886-1965) to a poem by Hakushu Kitahara (1885-1942); Chiisana Sora, an unusually conventional song by Toru Takemitsu (1930-1996), which he had written for a 1962 Japanese TV drama for children; and a Rogers & Hammerstein number, You'll Never Walk Alone.

The concert ended with a tune by one of the co-organizers, Hiromi Abe, who herself hails from Soma town in Fukushima prefecture. She told about the panicky times when it took her more than 24 hours after the earthquake to be able to get in touch with her parents who still live there (we had the same harrowing experience in trying to connect with my mother-in-law in Iwate). Abe's parents were safe but their town lost 500 people to the tsunami. Now Soma, just over 50 km from the Fukushima reactor, faces an uncertain future. Hiromi Abe ended the concert with her own song, To the People of Our Hometown Who Became the Light, with English lyrics translated by her friend Hitomi Demura-Devore. Sitting behind the grand piano, Abe accompanied herself as she sang, slightly tentatively, her mellow jazz-influenced ballad. It was clear to the audience that the words that she sang in a husky voice came straight from the heart.

Music for Lights was a benefit concert for Japan relief efforts organized by two young Japanese women, Jun Kubo and Hiromi Abe, based in New York. Both are versatile musicians comfortable in a variety of idioms ranging from Western classical to jazz. The concert was held in the beautiful Engelman Recital Hall of the Baruch Performing Arts Center in New York City's Gramercy Park neighborhood.

The two women started the concert with three duets for flute and piano. The first, Sonatine pour Flûte et Piano by Pierre Sancan (1916-2008), was a new acquaintance for me and I was taken by the beauty of the music. Jun Kubo's golden flute sounded lovely in the modern piece. Her tone is very smooth, especially in the lower register. I have earlier heard her in Meg Ogura's Pan Asian Jazz Orchestra and I have to say that her clean flute sounds more convincing in this classical context, rather than the contemporary band. Next Jun Kubo played Kojo no Tsuki, an old Japanese song which belongs to the shakuhachi repertoire. Kubo started the song with another type of bamboo flute, the transverse shinobue, before switching back to the Western flute. The arrangement was impressionistic and the overall performance quite low key. Hiromi Abe stumbled barely noticeably in some of the piano interludes. The ladies' performance ended with Sicilienne et Burlesque by Alfredo Casella (1883-1947), a rather playful piece in three parts, which suited the temperament of the two musicians well.

In between the pieces, Jun Kubo, who left Japan at 10 but keeps close contact there and even speaks the language fluently, told the audience how she had been in a meeting in Tokyo when the earthquake struck. By that time, she had already been five months pregnant. She had initially thought it was one of the "routine" Japanese earthquakes, but realized that this was something different when all the Japanese colleagues rushed screaming under their desks.

The star of the event was Jun Kubo's former teacher, Robert Dick. He has been called by some—and with some justification—the best flute player in the world. Dick is technically superior and enormously creative on flutes of various length. Like his young student, Dick is enormously versatile and at home in many kinds of music. Unlike her, though, he can be quite untamed when the music so requires. This was the third time I had the chance to witness his live performance and every time the setting has been entirely different. Again this evening the music presented a different side of the maestro. Dick briefed the rather conservative looking audience before starting his performance, saying that the best way to listen to his music was, well, just to listen to it: "Don't worry about the flute, that's my job."

Robert Dick began his segment of the concert with his own 1973 composition, Afterlight, an expressionistic exploration of the flute in which he blew two, three, even four tones at the same time, at times creating a rather eerie atmosphere. He then moved on to play the Sonata Appassionata composed by Sigfried Karg-Elert (1877-1933) in 1917, thus establishing his classical music bona fides before returning to his own compositions. What followed was Bells for Diz, a bass flute improvisation dedicated to Dizzy Gillespie who, as Robert Dick remarked, had two different stage personalities: one extremely focused when playing the trumpet and another, bubbling and lively when playing Afro-Caribbean percussion. Bells for Diz was an homage to the latter and the creative composer-performer used the big curved flute to generate an array of percussive sounds using the big keypads and blowing into the flute in various ways. The resulting music was inventive and joyful.

The final piece introduced a Dick invention, the glissando headjoint, which on the flute performs the same function as the whammy bar on an electric guitar. The inventor was initially inspired by Jimi Hendrix' guitar playing to explore how to create similar effects on the flute. He then worked over many years with instrument makers to realize his invention. The piece that concluded his part of the concert was a blues in which Robert Dick stretched the possibilities of the flute. The piece started and ended with slow slide guitar like licks. In between, he demonstrated a resourceful musicality and stunning technique moving from the blues to West African native flute tonalities and back via impressive runs.

Following Robert Dick in a concert is an unthankful position to be in. Therefore it was just as well that the next performer, singer Sahoko Sato, switched gears and genres entirely. The mezzo-soprano sang four songs accompanied by Rikako Asanuma (this young pianist is a native of Iwate, the prefecture in Japan closest to the epicenter of the March earthquake). These included Ave Maria by Pietro Mascagni (1963-1945); Kono Michi, composed by Kousaku Yamada (1886-1965) to a poem by Hakushu Kitahara (1885-1942); Chiisana Sora, an unusually conventional song by Toru Takemitsu (1930-1996), which he had written for a 1962 Japanese TV drama for children; and a Rogers & Hammerstein number, You'll Never Walk Alone.

The concert ended with a tune by one of the co-organizers, Hiromi Abe, who herself hails from Soma town in Fukushima prefecture. She told about the panicky times when it took her more than 24 hours after the earthquake to be able to get in touch with her parents who still live there (we had the same harrowing experience in trying to connect with my mother-in-law in Iwate). Abe's parents were safe but their town lost 500 people to the tsunami. Now Soma, just over 50 km from the Fukushima reactor, faces an uncertain future. Hiromi Abe ended the concert with her own song, To the People of Our Hometown Who Became the Light, with English lyrics translated by her friend Hitomi Demura-Devore. Sitting behind the grand piano, Abe accompanied herself as she sang, slightly tentatively, her mellow jazz-influenced ballad. It was clear to the audience that the words that she sang in a husky voice came straight from the heart.

Published on June 20, 2011 06:00

May 22, 2011

Oran Etkin @ Barbes, May 21, 2011

This Saturday night some forty people witnessed excellent intercultural musical cooperation in the shabby backroom of Barbès in Brooklyn where Israel-born Oran Etkin was joined by two Malian musicians, Makane Kouyate and Yacouba Sissoko. The combination of clarinet, kora and calabash is unusual enough, but the musical cross-fertilization and sheer talent of the trio made the event memorable. In the beginning, I thought the music lacked a bit in foundation, because there was no bass in the band. Both kora and clarinet play in treble pitches. However, this shortcoming—mostly in my own head and expectations—was soon overcome, largely because of Makane's amazing handling of the calabash. While playing complex rhythms and a remarkable range of tones by handling the single drum with his hands and fingers, he was also able to produce a steady bass beat with the base of his hand.

The music was basically based on West African rhythms and tones to which Oran brought his jazz and klezmer influenced clarinet. The concert started with a joyful tune, to be followed by a more melancholy love song, in which Oran switched to bass clarinet. The entire performance alternated between speedier jams and thoughtful and invariably very beautiful pieces mostly featuring the deep sounds of the larger curved clarinet.

Makane was the flashiest performer of the evening. In addition to his calabash, he sang the vocal numbers in an expressive lamenting voice. His percussion work was marvelous. Without warning, he would change the rhythm into double tempo and play flamboyant solos while the kora would keep the tune moving with a steady ostinato. All in all, there was a phenomenal cooperation between the musicians, with the clarinet and kora joining in unison as the drum would strike powerful thumps and bangs to signify a change in a segment or to end a song in a catchy phrase.

Barbès is a small bar and music space in Brooklyn's Park Slope. It is run by two Frenchmen who named it after the Paris neighborhood, which has a large North African immigrant population. The Brooklyn place has a distinctly Parisian underground feel and a clientele who perfectly fits into the scene. The age range is wide but a certain bohemian demeanor seems to unite the generations. The highly atmospheric music was further lubricated by freely flowing wine and cocktails, which the patrons imbibed in quantities. Although I was irrigating my own throat only with Diet Coke, I did not find any of my fellow audience to be the least annoying, not even those who were clearly quite well marinated.

Oran Etkin is a remarkably creative musician. A student of Yusef Lateef, he has taken after his legendary teacher in his open mind and broad musical vision that bridges a whole range of genres and cultural traditions in an eclectic manner. Lateef (born in 1920 and still going strong) has for decades been one of my greatest inspirations just for the reason of his limitless imagination and incorporation of African, Middle Eastern and Asian music into his own special style. In fact, one of the most intriguing numbers of the evening was a quirky slow blues-based tune that Oran said he had written for his mentor and played on a wailing clarinet. It also took the kora to directions and dimensions that are not normally heard on the stringed instrument. Yacouba Sissoko, however, is a master kora player who has the facility and musical sense to manage such challenges.

The concert was further spiced up by Oran's good-humored banter in between the tunes. He encouraged the audience to participate in an African style call and response chorus in one of the songs sung by Makane and he also gave people the license to dance, which they took up with delight. During the last number, Yekeke, I observed a middle-aged white couple who were totally absorbed in the moment. The woman shook in overtime as if possessed by a Mandingo spirit, while her partner wearing a pale blazer seemed to imitate former President George W. Bush when he joined in a tribal dance performance during one of his visits to Africa. But how could I blame them? Such was the intensity of the music and rhythm produced by this unorthodox acoustic trio.

Published on May 22, 2011 17:49

May 14, 2011

Delhi Heat

Delhi is hot. I mean not warm and sunny. I mean searing hot. The sun is shining from a cloudless sky and the temperature is around +40 degrees Celsius. As we walked the few hundred metres to have lunch at the India International Centre, Jayati with whom I am working here remarked: "You're lucky you weren't here last week; now it's a bit cooler." But according to the forecast would soon again get warmer—and indeed, on May 12th the year's record was broken with an official high of +43.1 degrees Celsius. Khushwant Singh, the famous Indian writer, sums it up in his latest, The Sunset Club: "It is said hell is a very hot place. If you want a foretaste of what may be your fate, you should spend the month of June in Delhi." It is now May, and maybe this is only a foretaste of what comes after.

Last time I was here, in January, just four months ago, it was freezing. The cold and damp fog of winter enveloped the city for weeks. A dozen or more people died as the frigid winds blew down to the northern plains from the Himalayas. Now they die of the heat. People with no shelter, exposed to the vagaries of climate. It is the rag pickers and the poor elderly who perish when the weather gets too cold or too hot. Or when it floods. Delhi is renowned for its floods when the monsoon rains come later in the year. The river Yamuna, which crosses the vast conglomeration, rises above its banks. The slums are soaked and again poor people are washed away with the waters. Which kills more people, I ask myself. So far, it is not the cold of the winter, although the seasons are getting quite extreme lately. Which way would I prefer myself, if I had the unenviable choice? They say one feels numb and warm before one passes away from freezing. Drowning is supposed to bring along a calm, with a light that shines presumably from somewhere above. But how do they know? As far as I can see, nobody has really died and come back to tell. I think that, considering the options, I'd prefer succumbing to the heat. Maybe my brain is already overheating, as I'm thinking this way.

In the evening the heat subsides with the sun and it is actually quite pleasant. Hot and dry, but not suffocating. A couple of nights ago, I headed out by myself, as my travelling companion had acquired an acute case of 'Delhi Belly.' No wonder, as in this heat all kinds of micro-organisms thrive. It was more of a wonder in January, when it was cold, that I acquired a bad case of the same ailment. I attribute it to complacency. Then I had thought it was safe enough to eat salads and other uncooked food. Obviously I was badly mistaken. After a couple of agonizing days when I finally was strong enough to get on my feet I headed to the Max Healthcare Super Speciality Hospital. I could see why today so many people, including Westerners, choose to have themselves treated in Indian hospitals if they get gravely ill. Of course, this option is only available to those who can afford it; which is to say, perhaps the top 10 percent of Indians plus the foreigners who see the value of being treated here. The Max was a sprawling complex in a park-like setting, spanking clean, friendly, efficient and cheap by Western standards. After just a quarter of an hour wait, I was examined by the highly professional Dr. Monica Mahajan who discharged me with a set of prescriptions that I was able to pick up from the ground floor dispensary on my way out. Give me this anytime over an overpriced and unfriendly American hospital where they ask for your religious affiliation and credit card before they even start treating you.

This recent night I was perfectly fine and jumped into the tiny white Tata taxi that I had hired on a weekly basis to take me around. I asked the dark skinned moustachioed driver, Shiva Dayal, to take me to Khan Market. I wanted to visit the two fabulous bookstores operating at the popular place. Just a few years ago, this was just a local market. Today it is one of the fanciest shopping areas in New Delhi with lots of boutiques frequented by fancy ladies sporting expensive jewellery and handbags. Khan Market was crowded, the lights of the shops beckoned browsers. I first went to Bahri Sons, but soon realized they were about to close for the night. The two young women tending the cashier were no longer interested in making a sell. Instead they were counting the stack of bills the shop had collected from customers during the day, joking and giggling with each other. I decided to head to Faqir-Chand & Sons, a small but magnificent book handler not far away in the same row of shops. They gave me more leeway time-wise, as well as service-wise, and I was able to browse through their amazing and amazingly disorganized collections. In a place where the newest books on politics and international affairs lie next to an assortment of other tomes with no apparent connection through their topics—Jack London's Call of the Wild adjacent to Mein Kampf; biographies of Che Guevara and the Beatles next to a photographic guide to sex positions from Kama Sutra—one can find true surprises that one just has to purchase. I picked up an inspiring anthology of Indian environmental writing, Voices in the Wilderness: Contemporary Wildlife Writings, edited by Prerna Singh Bindra.

Having picked my selection, I continued to an alley on the side of Khan Market where several small doors lead up to discreet little bars. Discreet only from the outside, however. I climbed the stairs to one called Route 04 and found a noisy room crowded with mostly young people, all Indian, consuming quantities of beer and cocktails. I could see plates of nachos carried to the tables to be consumed by the lively customers. Many of the women were breathtakingly beautiful, as many Indians are, with their large dark eyes lined with kohl. It was still early on a Monday evening, but the DJ in a corner was playing Led Zeppelin at high volume. A group of fashionable kids were sharing an oversized hookah at a close-by table. As it was happy hour, I got a second bottle of Tuborg for the same price. IMFL, they call it: Indian made foreign liquor. I could have stayed for the rest of the evening, but I was getting hungry and the somewhat depressing looking pseudo-Mexican/New Yorker snacks did not appeal to me.

I asked Shiva to recommend a restaurant with good Indian food that also served beer. The latter was a condition I would not compromise upon tonight. He said he knew just the place for me and off we drove to a new shopping centre close to Lodhi Gardens not far from Khan Market. The restaurant was called Pindi and boasted a neon sign promising genuine Mughal and Chinese cuisine. It was brightly lit with tables lining the sides of two adjacent oblong rooms. I sat at one and started browsing the menu. Soon Shiva returned with the bad news: the place had no beer. A discussion ensued involving the portentous proprietor and a couple of waiters mixing Hindi and English in a way that left me completely confused. I was led to a less conspicuous corner table and told to sit down. The paunchy owner assured me that things would work out. I would just have to be discreet about my beer. He only had two left and he had already told a group of some half a dozen foreigners sitting in the next room that there was no beer. The manager did not want them to see that someone arriving after them was actually served the cold drink. I agreed to be prudent and a waiter brought me a can carefully wrapped in a paper towel, so that it would not be obvious to any observer that the tin contained the coveted brew. With this, the evening proceeded. In my euphoria I ordered far too much food: succulent Rada mutton, with large chunks of soft lamb attached to bone served in an onion sauce containing minced lamb; delicious Karani Paneer, cottage cheese stewed in wonderful gravy; white long-grained rice.

India's economy is growing rapidly and in the West this is often seen as a threat. People in the US complain about outsourcing of jobs, as well as about bright and hardworking Indian professionals taking jobs in America. Some of it may be true, but the thriving modern sector is still only a thin layer: icing on the boiling cake of India. Most of India is still very poor and this poverty has both a geographical dimension as well as many social aspects. Often these overlap. The UN ranks India 119th among 169 countries based on the Human Development Index. This ranking does not only include monetary income but takes into account aspects such as health and education. This puts India into the 'medium human development' category. The index, however, hides huge differences between people. These differences can be explained in numerous ways: historical and structural factors, the highly varying government policies between states, inefficiencies, corruption, the caste system, rural to urban migration, etc.

Some Indian states lie very far behind Delhi, Mumbai and other major cities in the level of human development. Within the big cities, too, the inequality between people is staggering. Huge slums sprout beside shiny new skyscrapers and fancy villas. Little children and severely handicapped people beg at each intersection in Delhi accosting cars as they have to stop at traffic lights. New Delhi is a gorgeously beautiful city with ample green parks lining the streets. Its majestic avenues linking parts of the spread-out city are good for cars but the distances are long for people without transportation. Old Delhi is different, picturesque for a casual visitor, but rough on those who must live there. Teeming with humanity, its narrow streets are cramped up and dirty, buildings crumbling. Violence flares up easily in poverty.

On 11 May 2011, in the middle of my stay here, the Planning Commission of the Government of India redrew the official national poverty line at Rp. 20, or less than US$0.50, per day. The motivation can only be to reduce the number of people living below the poverty line, so that India doesn't look so bad in international comparisons or so that the government doesn't have to extend social services to as many people. But poverty remains, wherever you draw the line.

On a recent night, my friend Nidhi took me to the Sikh temple, Gurudwara Bangla Sahib. The place was crowded and very welcoming to people of any creed or colour. We removed our shoes and were given saffron headscarves to cover our hair in respect to the Sikh faith and culture. The gorgeous white temple was alive with music as people gathered there for prayers. We walked slowly around the vast square pool reflecting the lights of the temple in the dark evening. The Sikhs are proud people, never to be found among the beggars. Instead they have formed a supportive social system whereby any person in need—and one does not have to be Sikh—can find food and shelter in the temple. A tall and thin pole with lights on top has been raised high to guide people to the temple from a long distance. Also now we observed a large crowd of men and women, young and old, who had gathered waiting on the porch of a big hall to be fed. As we passed by, the gates were opened and the people streamed in for their free meal.

Our meal wasn't free at the Blues café and bar on Connaught Place at Delhi's commercial and business heart not too far from the temple. Sitting in the air-conditioned comfort listening to rather loud rock, we talked about the inequality and the persistence of abject poverty in India. Like Nidhi said, "Delhi is not a good place if you don't have money," The trouble is, there are so many who do not—and even the climate conspires against them.

Published on May 14, 2011 13:12

April 12, 2011

Musical Benefits for the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake Victims

On that fatal Friday, March 11, 2011, when the massive earthquake and tsunami struck Japan, the Tenri Gagaku orchestra was scheduled to play a concert at the Tenri Cultural Institute (TCI) near Union Square in Manhattan. Our phones were ringing as the TV poured live coverage of the wreckage in the distant island nation. My wife Yoko's home prefecture, Iwate, was at the heart of the disaster and she was not able to get in touch with family. She also plays ryuteki, a vertical bamboo flute in Tenri Gagaku. At last, it was decided that the concert would go on but that all proceeds from the ticket sales would be sent to Japan. Most certainly, this became the first in a long series of benefit concerts to aid the earthquake and tsunami victims. In the days and weeks to come when the extent of the disaster became clearer—and a nuclear hazard was added to the original woes—and that likely between 20,000 and 30,000 people had perished and many more left homeless and without livelihood, many musicians in New York, Japanese and foreign alike, joined forces to create some of the most innovative musical events to support the recovery in Japan. I had the honor of witnessing several of them and, thus in a small way, chipping in.

Tenri Gagaku @ Tenri Cultural Institute, 11 March 2011

Gagaku—literally translated as 'elegant music'—is the oldest form of orchestral music that has survived continuously in the world and Tenri Gagaku Music Society is arguably (but then again, I might be biased) the best gagaku group outside of Japan. The music has its roots in the Silk Road period during which gagaku-like music was widely played in various parts of Asia, ranging from China to Southeast Asia. From the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907) court in China it traveled east and landed in the Japanese islands via the Korean peninsula. In its new home, Gagaku was refined over centuries and passed down through generations of court musicians who belonged to hereditary guilds. While Gagaku has disappeared from countries in continental Asia, in Japan it was played in the homes of the military aristocracy and later preserved as living tradition in the ceremonies of the Imperial family.

The instrumentation used in gagaku today consists of a number of wind, string and percussion instruments, such as the ryuteki, hichiriki (a kind of double-reed oboe with a nasal tone), sho (a mouth organ), the biwa lute, the koto zither, and various drums, the kakko (small drum), shoko (metallic percussion) and taiko (large drum). Gagaku has a quality to it that sounds odd to the unaccustomed ear, but it definitely grows on you when you listen to it more.

On this evening Tenri Gagaku played a set of slow court pieces, starting with 'Etenraku.' This is probably the most well-known piece in the gagaku repertoire. It has a simple but catchy melody played alternately by hichiriki and ryuteki. Gagaku as music is monophonic, meaning that the melodies are played in unison by all instruments. The only real harmonies are provided by the sho, which provides a kind of solid mat of sound to the music (think harmonium in Indian traditional music).

The last piece of the concert was a dance number, bugaku, performed by Tazuko Ikedo dressed in a heavy and colorfully decorated costume. This was Tazuko's last performance before returning to Japan after several years in New York, so it was not to be missed. Her slow and deliberate movements to the plodding music produced a somewhat hypnotic mood that definitely captivated the audience of some 100 people who had crowded into the TCI hall. Gagaku and bugaku are a total experience that provide a feast for both the visual and auditory senses.

Concert for Japan @ Tenri Cultural Institute, 27 March 2011

Some two weeks later another Concert for Japan took place at TCI, this time featuring some of the foremost artists specializing in traditional Japanese music in New York. This concert was particularly precious for me, as it featured three shakuhachi masters: James Nyoraku Schlefer, Ronnie Nyogetsu Reishin Seldin and Ralph Samuelson. The concert started with 'Banshiki,' a tune belonging to the Meian Honkyoku tradition. The three masters were joined on stage with five shakuhachi students from the Tenri Cultural Institute. Clearly, 'Banshiki' was a tune that the students had to study and the group produced a decent version of the piece played on eight flutes that were only slightly out of tune. Some of the three men and two women were following closer in the footsteps of their teachers than others.

The concert also highlighted the versatility of the instrument to reflect the character of not only the music but equally the musicians. The temperaments of the three artists could not be more different and it was very interesting—and pleasurable—to observe how three players who are each trained in Japanese musical tradition and have reached the top levels in their chosen instrument could produce such differing artistic impressions. After the initial tune, the first concert performance was 'Haru no Umi' (or 'The Sea in Spring') featuring Nyoraku together with Masayo Ishigure, a masterful player of koto. 'Haru no Umi' is not a traditional Honkyaku piece, but rather a modern number composed by Michio Miyagi. It features lively dialogue between the two traditional instruments played in a not so traditional manner. The main theme of the composition is lovely and the variations indeed bring to mind the fickleness of the sea in springtime. It requires considerable skill from both instrumentalists and James played his part so smooth and clean that one could imagine listening to a Western flute instead of its bamboo ancestor.

'Jinbo Sanya' in the hands of Nyogetsu was an entirely different affair. The big man approaches shakuhachi from its original Buddhist perspective and had chosen this other Meian Honkyoku piece as his first solo number of the evening. The tune is haunting and Nyogetsu's interpretation used the full range of possibilities that the simple five-holed tube offers. The way he bent the tones using different techniques involving breathing, fingering, movement of lips, blowing angle and neck twists (known as kubi-furi, this is an essential, but hard to master technique for shakuhachi) produced remarkable sounds and effects that transported the listener to a medieval monastery in the misty mountains of Japan where the spirits of generations of Buddhist monks still linger.

Samuelson's first solo number was also a Honkyoku piece, but from a somewhat different tradition. The song entitled 'Choshi' was accompanied by the dancer Sachiyo Ito whose slow and sparse movements mirrored the music. Wearing a white kimono covered with a thin red coat, she moved deliberately with two fans in her hands to emphasize her choreography.

The first part of the concert ended with a koto solo by Masayo. It was 'Asa no Uta' or 'Morning Song' composed by her own teacher, Tadao Sawai. True to Sawai's style, this piece emphasized rapid movements and complex arpeggios. It was a koto player's delight, demonstrating virtuosity.

After the intermission, the three shakuhachi players returned each playing a solo piece. Nyoraku again started the set with a non-traditional tune, 'Ichijo' by Seiho Kinea. He explained to the audience in his jovial manner how the composer—a shamisen player who composed plenty of music for all Japanese instruments—had composed this tune in shock after a dear friend had "just dropped dead" after a pleasant evening they had spent together. The piece, in English 'Immutability,' conveyed the unpredictability of life and was therefore suitable for the occasion. I was not familiar with the composer, let alone the piece itself, but this would change after I heard the wonderful music. James was again smooth and perfect in his playing, but this time the song itself contained elements that were specifically shakuhachi-style, rather than any other flute. It was to me the highlight of the evening.

Ralph followed with a Honkyoku from the Kinko Ryu school, entitled 'Kyo Reibo.' Standing against the white wall and pieces of contemporary art Ralph, as usual dressed all in black, provided a stark contrast that suited the austerity of the song. His performance was less flashy or decorated than those of his peers, but it was deep, sincere and moving.

Nyogetsu returned with a jinashi shakuhachi that was longer than a regular shakuhachi and had a lower range. His final piece was another Meian Honkyoku with the title 'Futaiken Reibo.' The deep tonality of the slow moving tune resonated in the room, which has acoustics as if made for the sound of the flute.

The evening ended with a ritual: 'Chanting from the Heart' created by Sachiyo Ito. It involved Buddhist chants, dance movement and ringing of a traditional bell. Ito was this time dressed in an all white and light grey outfit. She was assisted by three younger ladies—Keiko Ehara, Hazuki Honma and Yukiko Yamamoto—all dressed in black trousers and shirts. One had the role of sitting on her knees throughout the performance, still and with a blank face, except when it was her turn to sound the large brass bell in front of her. As a final, all audience was invited to join in a walking meditation following the lead dancer.

Plastic Ono Band and Others @ Le Poisson Rouge, 29 March 2011

On the following Tuesday, an historical event took place at Le Poisson Rouge. Sean Ono Lennon had put together an amazing program for a Japan benefit concert. We arrived at the venue around 9:30 pm and the queue was literally around the corner from Bleecker Street down Thompson Street. Luckily the night was not particularly cold, as we waited in line until the doors opened at 10:30 pm. The crowd was very mixed, but many were middle aged and looked like they had a history of listening to rock. All the tables and chairs had been removed and we crowded around the slightly elevated stage. The floor was already flowing with beer, as someone had dropped a pint. We took our place close to a rowdy group of rather rough looking lesbians.

The music started when Miho Hattori and Yuka Honda climbed on the stage. The two Japanese woman form the band Cibo Matto, which clearly has a large following of its own. I understand very well, as their music is charming and intelligent despite being essentially produced by electronic keyboards by Yuka over which Miho sings. After two songs played by the duo the stage was suddenly crowded by musicians, including Yuko Araki who sat behind the drum kit, two horn players, a guitarist and Sean Lennon on bass. Understandably the sound expanded and the rhythms became funkier. A somewhat silly looking male singer whose name eluded me joined Miho in a flowing version of the Bossa Nova classic 'Águas de Março.' After a few intensive pieces in which the horns provided funky riffs and the interplay between bass and drums worked, Cibo Matto and their entourage left the stage.

After a short break, the house erupted, as Patti Smith entered the stage. Her set was entirely acoustic, except for the electric bass played by Tony Shanahan (during the concert, the bass was passed around and the two guitarists also took turns playing it, while Shanahan grabbed a guitar or sat behind the piano), and she took the audience by her sheer charisma and the amazing musical quality of the performance. The lanky Lenny Kaye, with his long hair flowing to his shoulders, played some exquisite solos on the acoustic guitar which were some of the most beautiful moments of the evening. Patti chatted with the audience and appeared to be in a good mood, although she did attempt to block the lenses of some of the more intrusive photographers next to the stage. The whole performance was thrilling and I had tears streaming down my cheeks when Patti and her crew performed a magical version of 'Ghost Dance' dedicated to the people of Japan: "We shall live again."

Shortly after midnight, Sean Lennon announced that his mother, Yoko Ono, had entered the premises and right at that moment the diminutive lady dressed in black and donning a hat and large sunglasses perched on her nose climbed on the stage. That is when the real party began, with a new version of Plastic Ono Band led by Sean setting the tempo. The band was extended, with three guitars (including Sean and Shimmy Hirotaka Shimizu), keyboards, drums and trumpet. Time has not mellowed Yoko who started—and ended—the show with her trademark wails and screams. Throughout the night she jumped around the stage energetically, betraying her age: in February, Yoko Ono had just turned 78! Apart from directing the music, Sean played some of the most inspired guitar solos of the evening. Given that women so often in rock music have been relegated to the role of singers and dancers, it was very satisfying to see three highly professional female musicians solidifying the backbone of the band: tiny Yuko Araki whose tight beats kept the music rolling; the tall supermodel looking bassist who excelled in particular in some of the slower numbers where her musicality came through best; and Yuka Honda handling the keyboards.

As the night progressed, more guests climbed on the stage. The most prominent of them was Lou Reed. At mere 69, he should have been a real spring chicken compared with the evening's leading lady, but Reed appeared stiff and unsteady in his walking. He performed one long number with the band, a heavy rolling rock song, egging the little drummer girl to beat the cans ever harder. A man in the audience next to me said, incredulously, "I can't believe that these two are both together on stage!" I don't know whether this had ever happened before, but it was indeed historical to have Yoko Ono, Lou Reed and Patti Smith all in one concert! Another guest star was Antony who sang a number of duets with Yoko Ono. The large man with long hair and a baby face sang with a sweet voice and the entire impression was quite a contrast to the older star of the night.

The evening culminated in an extended version of 'Give Peace a Chance' during which most of the musicians who had performed during the evening returned on the stage. Sean Lennon standing next to his mother led them into the iconic song made famous by his father. Miho Hattori took the lead during the second verse until the others—and the audience—joined in. At 01:30 am as the concert wound to a close, we all felt the warmth and love channeled by the music to the people in Japan.

Taka Kigawa @ Le Poisson Rouge, 2 April 2011

When we returned to Le Poisson Rouge later in the same week, the place had been restored to its normal setting with tightly packed tables. The waitresses were cruising between them while we settled at a table in the second row in front of the stage. We were early and had time for a light meal before the show.

I used the word "show" intentionally, as that is what was in store for us. Taka Kigawa is a classical musician who plays the music as the composers meant it to be played without any tricks or gimmicks. But his interpretations are strong and engaging—and he communicates with the audience. He talked about the concert and commented on the pieces in between. Dressed in an open red shirt and black jeans, his long dark hair covering part of his face, Taka looked more like a rock musician than a classical pianist. All of this is why he has created a following that tonight sold out the large space. For tonight, Taka had put together an extraordinary program that would captivate everyone in the room. And as he would explain, there was a logic behind every piece that he had placed on the program. Obviously, much of the music would be Japanese, but those pieces that were not all had a reason to be included.

The concert started with two contemporary pieces by Japanese composer: 'atardecer/a...retraced' by Hiroya Miura and 'Crystalline' by Karen Tanaka. Taka is a specialist in contemporary music and plays it forcefully and with amazing concentration. However, on this emotional evening it was important to connect with everyone in the audience. This happened next when Taka played 'Images, Book I' by Debussy, with its three parts: 'Reflets dans l'eau,' 'Hommage à Rameau,' and 'Mouvement.' These lovely pieces demonstrated Taka's fluency in Debussy's language and the fluidity of especially his left hand. This was followed by two works by Chopin, 'Prelude in C-sharp minor, Op. 45' and the wonderful 'Ballade No. 4 in F minor, Op. 52,' Chopin's last, which Taka interpreted with incredible dynamism and emotion, earning him a huge ovation from the audience. Speaking about these choices, Taka explained how Chopin, while living in Paris, never forgot about and was always concerned about his home country of Poland, implying a similar feeling inside of him regarding Japan.

Next Kigawa inserted three more pieces by Japanese contemporary composers: 'Rain Tree Sketch II (In Memoriam Olivier Messiaen)' by Toru Takemitsu; a short piece, like the title implies, by Toshio Hosokawa, 'Haiku for Pierre Boulez,' and 'Joule' by Dai Fujikura, which Taka had premiered in the USA in January 2010.

The rest of the concert consisted of guaranteed crowd pleasers that Taka Kigawa played with unusual flair. Stravinsky's 'Trois Mouvements de Petrouchka,' derived from the ballet and transcribed for solo piano by the composer himself, in Taka's performance was simply incredible. The rhythm, the power, the energy just overwhelmed the audience who exploded in applause and cheers. The pianist came to the edge of the stage to take a bow after the piece, which could have been the grand finale for the concert. But he remembered having scheduled one more number in the program, Ravel's lovely 'Pavane pour une infante défunte.' The exquisite and pensive piece brought the thoughts back to the sadness of the situation in Japan.

Inspired by the cause and the enthusiasm of the audience, Taka took not one, but four encores, the highlight of which was Debussy's 'L'isle joyeuse,' an obvious reference to what the pianist—and we all—hope that Japan will once again be in the not too distant future.

Concert for Japan @ The Japan Society, 9 April 2011

The Japan Society had put up a nonstop musical program that lasted for 12 straight hours on this Saturday. Finally, after a long and cold winter there was spring in the air and the sun was shining from a blue sky as Yoko and I approached the Society's headquarters in front of Dag Hammarsköljd Park in Midtown. There was a large crowd gathered on the street and in the park to listen to a Taiko drum performance outside of the entrance to the premises. There were also vendors selling Japanese food from several stalls, proceeds from which would be donated to the earthquake relief fund. The day's program alternated between free concerts of both Japanese traditional music and Western classical music, with two sold-out 'Gala Blocks' with reserved seating and big ticket items. We heard performances by Sadahiro Kakitani on solo ryuteki; Masayo Ishigure with a large group of koto, shamisen and shakuhachi players; James Nyoraku Schlefer playing his shakuhachi both solo and in group; and Yumi Kurosawa, whose piece on a 20-string koto impressed us.

For us the main attraction of the day was the first of the Gala Blocks, which featured Philip Glass. While we have often heard his music played in concerts in several cities, it was the first time ever to witness the composer himself behind the piano playing his own music. There was excitement in the air as we took our seats in the middle of the second row. The concert started with a performance in which Hal Willner read poetry by Allen Ginsberg accompanied by Philip Glass. Both of the performers had personally known Ginsberg and the jolly Willner explained the context of the poems that had been written over a lengthy period of time from the 1950s to the 1970s. There were some powerful images (and some very amusing ones, too) conjured up by the poems (note to self: reacquaint yourself with Ginsberg's works) and the pianist followed and strengthened the moods expertly.

Musically, however, what followed was more interesting. Philip Glass played against a film by Harry Smith, 'Early Abstractions' from 1946. I was not familiar with Smith, but according to Hal Wilner he was one of the greatest creative geniuses of the 20th Century, creating films and other works, including an anthology of American music, while never gaining wide recognition. As the abstract pictures moved on the large screen behind the piano, Philip Glass created an equally hectic music through his trademark fast and repetitive motifs that flowed into the hall seamlessly mixing with the visual media.

The final part of the concert was a 20-minute collective creation by three unorthodox features of New York's art scene: John Zorn, Laurie Anderson and Lou Reed. Zorn with his alto saxophone was flanked on both sides by arrays of electronics associated with Anderson and Reed. The latter took a very different role today from his recent rocker performance with the Plastic Ono Band. This was experimental music in which his contributions were through innovative effects on guitar and other electronics. The piece was loosely structured around segments and motifs but most of the playing appeared improvised. Laurie Anderson alternated between solos and accompanying effects on her electric violin. John Zorn blew into his alto at times lyrically just to be followed by aggressive bursts of raw energy as the piece grew in intensity. The culmination was when the trio was joined on stage by a Japanese Taiko player who beat thunderously into the large drum towards the final shock and awe of the music.

The above constitutes just a sample of all great (and some less so) music played to benefit the victims of the earthquake and tsunami that struck Northeastern Japan in March. It is wonderful to see all the empathy and support for the people on the other side of the world facing an unimaginable challenge to recover from the loss of families and loved ones and to start rebuilding the nation from the rubble. But this will not be the first time Japan raises from destruction. I do believe in the resilience of the nation.

Tenri Gagaku @ Tenri Cultural Institute, 11 March 2011

Gagaku—literally translated as 'elegant music'—is the oldest form of orchestral music that has survived continuously in the world and Tenri Gagaku Music Society is arguably (but then again, I might be biased) the best gagaku group outside of Japan. The music has its roots in the Silk Road period during which gagaku-like music was widely played in various parts of Asia, ranging from China to Southeast Asia. From the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907) court in China it traveled east and landed in the Japanese islands via the Korean peninsula. In its new home, Gagaku was refined over centuries and passed down through generations of court musicians who belonged to hereditary guilds. While Gagaku has disappeared from countries in continental Asia, in Japan it was played in the homes of the military aristocracy and later preserved as living tradition in the ceremonies of the Imperial family.

The instrumentation used in gagaku today consists of a number of wind, string and percussion instruments, such as the ryuteki, hichiriki (a kind of double-reed oboe with a nasal tone), sho (a mouth organ), the biwa lute, the koto zither, and various drums, the kakko (small drum), shoko (metallic percussion) and taiko (large drum). Gagaku has a quality to it that sounds odd to the unaccustomed ear, but it definitely grows on you when you listen to it more.

On this evening Tenri Gagaku played a set of slow court pieces, starting with 'Etenraku.' This is probably the most well-known piece in the gagaku repertoire. It has a simple but catchy melody played alternately by hichiriki and ryuteki. Gagaku as music is monophonic, meaning that the melodies are played in unison by all instruments. The only real harmonies are provided by the sho, which provides a kind of solid mat of sound to the music (think harmonium in Indian traditional music).

The last piece of the concert was a dance number, bugaku, performed by Tazuko Ikedo dressed in a heavy and colorfully decorated costume. This was Tazuko's last performance before returning to Japan after several years in New York, so it was not to be missed. Her slow and deliberate movements to the plodding music produced a somewhat hypnotic mood that definitely captivated the audience of some 100 people who had crowded into the TCI hall. Gagaku and bugaku are a total experience that provide a feast for both the visual and auditory senses.

Concert for Japan @ Tenri Cultural Institute, 27 March 2011

Some two weeks later another Concert for Japan took place at TCI, this time featuring some of the foremost artists specializing in traditional Japanese music in New York. This concert was particularly precious for me, as it featured three shakuhachi masters: James Nyoraku Schlefer, Ronnie Nyogetsu Reishin Seldin and Ralph Samuelson. The concert started with 'Banshiki,' a tune belonging to the Meian Honkyoku tradition. The three masters were joined on stage with five shakuhachi students from the Tenri Cultural Institute. Clearly, 'Banshiki' was a tune that the students had to study and the group produced a decent version of the piece played on eight flutes that were only slightly out of tune. Some of the three men and two women were following closer in the footsteps of their teachers than others.

The concert also highlighted the versatility of the instrument to reflect the character of not only the music but equally the musicians. The temperaments of the three artists could not be more different and it was very interesting—and pleasurable—to observe how three players who are each trained in Japanese musical tradition and have reached the top levels in their chosen instrument could produce such differing artistic impressions. After the initial tune, the first concert performance was 'Haru no Umi' (or 'The Sea in Spring') featuring Nyoraku together with Masayo Ishigure, a masterful player of koto. 'Haru no Umi' is not a traditional Honkyaku piece, but rather a modern number composed by Michio Miyagi. It features lively dialogue between the two traditional instruments played in a not so traditional manner. The main theme of the composition is lovely and the variations indeed bring to mind the fickleness of the sea in springtime. It requires considerable skill from both instrumentalists and James played his part so smooth and clean that one could imagine listening to a Western flute instead of its bamboo ancestor.

'Jinbo Sanya' in the hands of Nyogetsu was an entirely different affair. The big man approaches shakuhachi from its original Buddhist perspective and had chosen this other Meian Honkyoku piece as his first solo number of the evening. The tune is haunting and Nyogetsu's interpretation used the full range of possibilities that the simple five-holed tube offers. The way he bent the tones using different techniques involving breathing, fingering, movement of lips, blowing angle and neck twists (known as kubi-furi, this is an essential, but hard to master technique for shakuhachi) produced remarkable sounds and effects that transported the listener to a medieval monastery in the misty mountains of Japan where the spirits of generations of Buddhist monks still linger.

Samuelson's first solo number was also a Honkyoku piece, but from a somewhat different tradition. The song entitled 'Choshi' was accompanied by the dancer Sachiyo Ito whose slow and sparse movements mirrored the music. Wearing a white kimono covered with a thin red coat, she moved deliberately with two fans in her hands to emphasize her choreography.

The first part of the concert ended with a koto solo by Masayo. It was 'Asa no Uta' or 'Morning Song' composed by her own teacher, Tadao Sawai. True to Sawai's style, this piece emphasized rapid movements and complex arpeggios. It was a koto player's delight, demonstrating virtuosity.

After the intermission, the three shakuhachi players returned each playing a solo piece. Nyoraku again started the set with a non-traditional tune, 'Ichijo' by Seiho Kinea. He explained to the audience in his jovial manner how the composer—a shamisen player who composed plenty of music for all Japanese instruments—had composed this tune in shock after a dear friend had "just dropped dead" after a pleasant evening they had spent together. The piece, in English 'Immutability,' conveyed the unpredictability of life and was therefore suitable for the occasion. I was not familiar with the composer, let alone the piece itself, but this would change after I heard the wonderful music. James was again smooth and perfect in his playing, but this time the song itself contained elements that were specifically shakuhachi-style, rather than any other flute. It was to me the highlight of the evening.

Ralph followed with a Honkyoku from the Kinko Ryu school, entitled 'Kyo Reibo.' Standing against the white wall and pieces of contemporary art Ralph, as usual dressed all in black, provided a stark contrast that suited the austerity of the song. His performance was less flashy or decorated than those of his peers, but it was deep, sincere and moving.

Nyogetsu returned with a jinashi shakuhachi that was longer than a regular shakuhachi and had a lower range. His final piece was another Meian Honkyoku with the title 'Futaiken Reibo.' The deep tonality of the slow moving tune resonated in the room, which has acoustics as if made for the sound of the flute.

The evening ended with a ritual: 'Chanting from the Heart' created by Sachiyo Ito. It involved Buddhist chants, dance movement and ringing of a traditional bell. Ito was this time dressed in an all white and light grey outfit. She was assisted by three younger ladies—Keiko Ehara, Hazuki Honma and Yukiko Yamamoto—all dressed in black trousers and shirts. One had the role of sitting on her knees throughout the performance, still and with a blank face, except when it was her turn to sound the large brass bell in front of her. As a final, all audience was invited to join in a walking meditation following the lead dancer.

Plastic Ono Band and Others @ Le Poisson Rouge, 29 March 2011

On the following Tuesday, an historical event took place at Le Poisson Rouge. Sean Ono Lennon had put together an amazing program for a Japan benefit concert. We arrived at the venue around 9:30 pm and the queue was literally around the corner from Bleecker Street down Thompson Street. Luckily the night was not particularly cold, as we waited in line until the doors opened at 10:30 pm. The crowd was very mixed, but many were middle aged and looked like they had a history of listening to rock. All the tables and chairs had been removed and we crowded around the slightly elevated stage. The floor was already flowing with beer, as someone had dropped a pint. We took our place close to a rowdy group of rather rough looking lesbians.

The music started when Miho Hattori and Yuka Honda climbed on the stage. The two Japanese woman form the band Cibo Matto, which clearly has a large following of its own. I understand very well, as their music is charming and intelligent despite being essentially produced by electronic keyboards by Yuka over which Miho sings. After two songs played by the duo the stage was suddenly crowded by musicians, including Yuko Araki who sat behind the drum kit, two horn players, a guitarist and Sean Lennon on bass. Understandably the sound expanded and the rhythms became funkier. A somewhat silly looking male singer whose name eluded me joined Miho in a flowing version of the Bossa Nova classic 'Águas de Março.' After a few intensive pieces in which the horns provided funky riffs and the interplay between bass and drums worked, Cibo Matto and their entourage left the stage.

After a short break, the house erupted, as Patti Smith entered the stage. Her set was entirely acoustic, except for the electric bass played by Tony Shanahan (during the concert, the bass was passed around and the two guitarists also took turns playing it, while Shanahan grabbed a guitar or sat behind the piano), and she took the audience by her sheer charisma and the amazing musical quality of the performance. The lanky Lenny Kaye, with his long hair flowing to his shoulders, played some exquisite solos on the acoustic guitar which were some of the most beautiful moments of the evening. Patti chatted with the audience and appeared to be in a good mood, although she did attempt to block the lenses of some of the more intrusive photographers next to the stage. The whole performance was thrilling and I had tears streaming down my cheeks when Patti and her crew performed a magical version of 'Ghost Dance' dedicated to the people of Japan: "We shall live again."

Shortly after midnight, Sean Lennon announced that his mother, Yoko Ono, had entered the premises and right at that moment the diminutive lady dressed in black and donning a hat and large sunglasses perched on her nose climbed on the stage. That is when the real party began, with a new version of Plastic Ono Band led by Sean setting the tempo. The band was extended, with three guitars (including Sean and Shimmy Hirotaka Shimizu), keyboards, drums and trumpet. Time has not mellowed Yoko who started—and ended—the show with her trademark wails and screams. Throughout the night she jumped around the stage energetically, betraying her age: in February, Yoko Ono had just turned 78! Apart from directing the music, Sean played some of the most inspired guitar solos of the evening. Given that women so often in rock music have been relegated to the role of singers and dancers, it was very satisfying to see three highly professional female musicians solidifying the backbone of the band: tiny Yuko Araki whose tight beats kept the music rolling; the tall supermodel looking bassist who excelled in particular in some of the slower numbers where her musicality came through best; and Yuka Honda handling the keyboards.

As the night progressed, more guests climbed on the stage. The most prominent of them was Lou Reed. At mere 69, he should have been a real spring chicken compared with the evening's leading lady, but Reed appeared stiff and unsteady in his walking. He performed one long number with the band, a heavy rolling rock song, egging the little drummer girl to beat the cans ever harder. A man in the audience next to me said, incredulously, "I can't believe that these two are both together on stage!" I don't know whether this had ever happened before, but it was indeed historical to have Yoko Ono, Lou Reed and Patti Smith all in one concert! Another guest star was Antony who sang a number of duets with Yoko Ono. The large man with long hair and a baby face sang with a sweet voice and the entire impression was quite a contrast to the older star of the night.

The evening culminated in an extended version of 'Give Peace a Chance' during which most of the musicians who had performed during the evening returned on the stage. Sean Lennon standing next to his mother led them into the iconic song made famous by his father. Miho Hattori took the lead during the second verse until the others—and the audience—joined in. At 01:30 am as the concert wound to a close, we all felt the warmth and love channeled by the music to the people in Japan.

Taka Kigawa @ Le Poisson Rouge, 2 April 2011

When we returned to Le Poisson Rouge later in the same week, the place had been restored to its normal setting with tightly packed tables. The waitresses were cruising between them while we settled at a table in the second row in front of the stage. We were early and had time for a light meal before the show.

I used the word "show" intentionally, as that is what was in store for us. Taka Kigawa is a classical musician who plays the music as the composers meant it to be played without any tricks or gimmicks. But his interpretations are strong and engaging—and he communicates with the audience. He talked about the concert and commented on the pieces in between. Dressed in an open red shirt and black jeans, his long dark hair covering part of his face, Taka looked more like a rock musician than a classical pianist. All of this is why he has created a following that tonight sold out the large space. For tonight, Taka had put together an extraordinary program that would captivate everyone in the room. And as he would explain, there was a logic behind every piece that he had placed on the program. Obviously, much of the music would be Japanese, but those pieces that were not all had a reason to be included.

The concert started with two contemporary pieces by Japanese composer: 'atardecer/a...retraced' by Hiroya Miura and 'Crystalline' by Karen Tanaka. Taka is a specialist in contemporary music and plays it forcefully and with amazing concentration. However, on this emotional evening it was important to connect with everyone in the audience. This happened next when Taka played 'Images, Book I' by Debussy, with its three parts: 'Reflets dans l'eau,' 'Hommage à Rameau,' and 'Mouvement.' These lovely pieces demonstrated Taka's fluency in Debussy's language and the fluidity of especially his left hand. This was followed by two works by Chopin, 'Prelude in C-sharp minor, Op. 45' and the wonderful 'Ballade No. 4 in F minor, Op. 52,' Chopin's last, which Taka interpreted with incredible dynamism and emotion, earning him a huge ovation from the audience. Speaking about these choices, Taka explained how Chopin, while living in Paris, never forgot about and was always concerned about his home country of Poland, implying a similar feeling inside of him regarding Japan.

Next Kigawa inserted three more pieces by Japanese contemporary composers: 'Rain Tree Sketch II (In Memoriam Olivier Messiaen)' by Toru Takemitsu; a short piece, like the title implies, by Toshio Hosokawa, 'Haiku for Pierre Boulez,' and 'Joule' by Dai Fujikura, which Taka had premiered in the USA in January 2010.

The rest of the concert consisted of guaranteed crowd pleasers that Taka Kigawa played with unusual flair. Stravinsky's 'Trois Mouvements de Petrouchka,' derived from the ballet and transcribed for solo piano by the composer himself, in Taka's performance was simply incredible. The rhythm, the power, the energy just overwhelmed the audience who exploded in applause and cheers. The pianist came to the edge of the stage to take a bow after the piece, which could have been the grand finale for the concert. But he remembered having scheduled one more number in the program, Ravel's lovely 'Pavane pour une infante défunte.' The exquisite and pensive piece brought the thoughts back to the sadness of the situation in Japan.

Inspired by the cause and the enthusiasm of the audience, Taka took not one, but four encores, the highlight of which was Debussy's 'L'isle joyeuse,' an obvious reference to what the pianist—and we all—hope that Japan will once again be in the not too distant future.

Concert for Japan @ The Japan Society, 9 April 2011

The Japan Society had put up a nonstop musical program that lasted for 12 straight hours on this Saturday. Finally, after a long and cold winter there was spring in the air and the sun was shining from a blue sky as Yoko and I approached the Society's headquarters in front of Dag Hammarsköljd Park in Midtown. There was a large crowd gathered on the street and in the park to listen to a Taiko drum performance outside of the entrance to the premises. There were also vendors selling Japanese food from several stalls, proceeds from which would be donated to the earthquake relief fund. The day's program alternated between free concerts of both Japanese traditional music and Western classical music, with two sold-out 'Gala Blocks' with reserved seating and big ticket items. We heard performances by Sadahiro Kakitani on solo ryuteki; Masayo Ishigure with a large group of koto, shamisen and shakuhachi players; James Nyoraku Schlefer playing his shakuhachi both solo and in group; and Yumi Kurosawa, whose piece on a 20-string koto impressed us.

For us the main attraction of the day was the first of the Gala Blocks, which featured Philip Glass. While we have often heard his music played in concerts in several cities, it was the first time ever to witness the composer himself behind the piano playing his own music. There was excitement in the air as we took our seats in the middle of the second row. The concert started with a performance in which Hal Willner read poetry by Allen Ginsberg accompanied by Philip Glass. Both of the performers had personally known Ginsberg and the jolly Willner explained the context of the poems that had been written over a lengthy period of time from the 1950s to the 1970s. There were some powerful images (and some very amusing ones, too) conjured up by the poems (note to self: reacquaint yourself with Ginsberg's works) and the pianist followed and strengthened the moods expertly.

Musically, however, what followed was more interesting. Philip Glass played against a film by Harry Smith, 'Early Abstractions' from 1946. I was not familiar with Smith, but according to Hal Wilner he was one of the greatest creative geniuses of the 20th Century, creating films and other works, including an anthology of American music, while never gaining wide recognition. As the abstract pictures moved on the large screen behind the piano, Philip Glass created an equally hectic music through his trademark fast and repetitive motifs that flowed into the hall seamlessly mixing with the visual media.

The final part of the concert was a 20-minute collective creation by three unorthodox features of New York's art scene: John Zorn, Laurie Anderson and Lou Reed. Zorn with his alto saxophone was flanked on both sides by arrays of electronics associated with Anderson and Reed. The latter took a very different role today from his recent rocker performance with the Plastic Ono Band. This was experimental music in which his contributions were through innovative effects on guitar and other electronics. The piece was loosely structured around segments and motifs but most of the playing appeared improvised. Laurie Anderson alternated between solos and accompanying effects on her electric violin. John Zorn blew into his alto at times lyrically just to be followed by aggressive bursts of raw energy as the piece grew in intensity. The culmination was when the trio was joined on stage by a Japanese Taiko player who beat thunderously into the large drum towards the final shock and awe of the music.

The above constitutes just a sample of all great (and some less so) music played to benefit the victims of the earthquake and tsunami that struck Northeastern Japan in March. It is wonderful to see all the empathy and support for the people on the other side of the world facing an unimaginable challenge to recover from the loss of families and loved ones and to start rebuilding the nation from the rubble. But this will not be the first time Japan raises from destruction. I do believe in the resilience of the nation.

Published on April 12, 2011 07:08

March 13, 2011

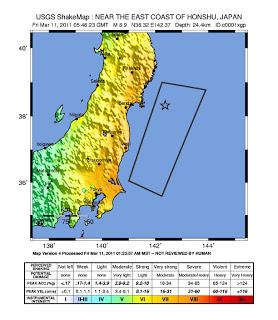

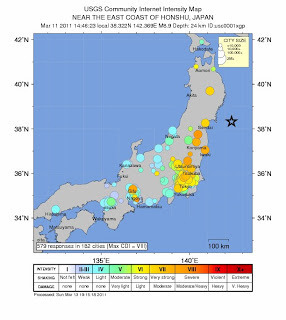

Massive earthquake and tsunami devastate northeastern Japan

On Friday, 11 March 2011, at 14:46 hrs, disaster struck Japan. One of the largest earthquakes on record struck just off the Pacific coast of the island nation. The shaking lasted for a full five minutes—a terrifyingly long time when one entirely loses orientation, may not be able to stand up, with everything falling down around you, walls and houses crumbling, the rumble of the earth drowning all other sounds—triggering a massive tsunami. Because the epicentre was so close to the coast, there was hardly any warning or time to evacuate. The first waves reached the Sanriku coast within ten minutes completely overrunning the towns and ports leaving total destruction in their wake.

The worst affected areas were in the northeast of the main island, Honshu. The prefectures of Miyagi and Iwate bore the brunt of the force. Iwate is the home area of my wife's family where we have also planned to return eventually to live in the lovely valleys between forested mountains. It has been considered the most stable region of Japan, least at risk from earthquakes. There was no way to get in touch with relatives and friends as, of course, all communications were cut. Whatever communications infrastructure was left standing was immediately overstretched as millions of people tried to contact their loved ones. We were left helplessly glued to TV Japan that broadcast horrifying live footage from the disaster zones. Initial films were mostly from Tokyo with some footage shot from helicopters flying over the coast. The northern Tohoku region where Miyagi, Iwate and Aomori Prefectures are located was cut off the rest of the world.

Tohoku's largest city, Sendai, situated on higher ground and away from the sea was largely spared from major damage. The city airport closer to the coast was not so lucky. Cameras from there showed the massive wave sweeping slowly across the runways. Large jet planes floated away like toy models. Aerial shots from the close by mountain areas showed huge liquefaction of the soil, again in slow motion, wiping away entire villages, houses crumbling and being washed down the slopes into the sea. The destruction there was complete.

The magnitude of the earthquake and the ensuing tsunami entirely overwhelmed all preparedness plans in Japan, probably the best prepared country in the world. The infrastructure was destroyed to such an extent that no rescue teams could reach the area. Places that we so well know were no more. Kesennuma, a major port city on the Sanriku coast in Miyagi, was gone. First the tsunami swept across the entire low lying valley. When it receded, fires that ensued as gas pipelines were destroyed finished the job burning down the entire old wooden town. Kesennuma had been the site of a large fishing port and the centre of the Pacific shark fisheries just because of the shape of its natural harbour. Now this same geographic advantage had provided the tsunami a perfect entrance to the harbour bowl allowing the water to rise unhindered into the city. A couple of years ago we spent some lovely time in Kesennuma enjoying its fabulous seafood. Yoko's old high school geography teacher, Abe Take Sensei, took us to his favourite restaurant and was slightly upset with me for ordering simple grilled fish in this haven of amazing specialities from the sea. Abe Take Sensei himself ordered shark's heart to accompany his beer. We all feasted on the weird looking sunfish from deep under the ocean. Now, none of these places would no longer be in existence.

Luckily, Yoko's family resides mostly further inland, in and around Oshu-shi straight north from Sendai halfway to Morioka, the second largest city in Tohoku. Their towns—Mizusawa, Esashi Maesawa, Koromokawa—were at least out of the reach of the tsunami. Late on Friday afternoon when it was already night in Japan we finally received a brief text message from an aunt, Shigeyo. She had been in touch with Yoko's mother Tomoko. Both elderly ladies were fine, but there was no electricity and no water. The entire area was in pitch darkness and it was cold. Snow was falling on the ravaged land. Nevertheless, it was a huge relief to hear from the family.

Another major worry, however, remained. Yoko's 15 year old nephew Hiromichi and his mother Miho lived in Hakodate, a coastal city on the northern island of Hokkaido and there were reports about the tsunami having soaked the city.

I was scheduled to fly into Japan in the beginning of the coming week in connection with an Asian business trip, but I cancelled the trip. There was no sense in going and adding to the chaos and possibly hampering transportation of relief workers and supplies. Some economists were already calculating how such dedication of port facilities to relief needs would be blocking Japan's exports. Other economists were estimating how the reconstruction that follows might actually provide a boost to Japanese manufacturing and economy. Economists are a different breed. No one was able to estimate the human death toll from the disaster, but there were reports of 200-300 bodies floating in the water on Miyagi coast, whom nobody was able to reach. But for the economists, there were more important and urgent calculations to be made.

On Saturday there was more live footage from Sanriku. Rikuzentakada, Ofunato, Kamaishi and other towns had been completely wiped out. It was impossible to imagine how one might even begin clearing the debris and start reconstruction. Only some sturdier concrete buildings stood amongst the rubble. Some lucky people had managed to reach their rooftops or run up the slopes to be saved only to observe the annihilation of their homes. Many old people didn't make it. In Kamaishi there was a home for disabled children. It seems it was gone with the waves.