Juha I. Uitto's Blog, page 12

March 11, 2012

Oh, Linda Oh!

The Harlem in the Himalayas nights at the Rubin Museum of Art are amongst the most innovative and enjoyable events in New York. They take place at irregular intervals on Friday evenings every couple of months, which is probably good. It would be nice to have them more often, but this way the quality and freshness of the music can be guaranteed.

On the first Friday of this month I headed there to catch a rising star in the jazz world, Linda Oh, whom I had read about but whose music I had never heard. The ground floor café space—spacious yet intimate—was slowly filling up and an extra cash bar had been set up in a corner, but many of the patrons were still browsing in the museum shop that, faithful to the museum's theme, displays a comprehensive collection of works focusing on Buddhism and other Eastern cultural topics.

As always, the concert took place in the basement concert hall, which is not set up as your usual concert hall. While the stage is rather large and elevated like in a traditional theater, the chairs are arranged so as to allow for small tables in between for the audience to place their drinks on. When the doors opened just before 7 pm, a fair proportion of the people in the bookstore and lounge moved down to hear the concert. The audience was mixed in age, gender and ethnicity, which to me is always a great plus in itself.

Linda Oh presented her trio consisting of Ambrose Akinmusire on trumpet, Tommy Crane on drums and the leader herself on the bass. She began the concert with a bass solo turning into a vamp that the two other musicians joined in. The band settled into an easy slow groove that immediately grabbed the audience with it. We would hear 1.5 hours of contemporary jazz played on purely acoustic instruments, with interesting harmonies and complex, ever-changing rhythms. Yet, this was music that people could easily relate to.

The Malaysian-born, Australian-raised composer-musician writes music that is both innovative and beautiful, often an elusive goal for contemporary musicians. Linda Oh hasn't followed the usual path through Berklee College of Music that so many young jazz musicians now emerge from. Instead, she studied at the Western Australia Academy of Performing Arts. She then moved to the US and completed a master's degree at the Manhattan School of Music, where she now teaches the bass. Her Aussie accent, albeit moderated by the stay in New York, was still audible as the sympathetic young lady introduced the music in between pieces.

Apart from being a technically and musically skilled bassist, what attracted me was her composing. Her tunes have beautiful melodies that appear deceivingly simple. The trio, with no instrument playing the chords, might appear somewhat limiting harmonically. Then again, the set chord changes played by a piano or guitar can also in themselves become a restriction for the musicians to venture outside. Consequently, many modern jazz players—from Gerry Mulligan and Ornette Coleman to Dave Holland and Joshua Redman—have chosen the more open format. In this case, the Linda Oh Trio was in many ways having the best of both worlds. While they created ample space for adventurousness, there was also structure and harmony in the music. The melodies were often played by the trumpet and the bass together or alternately, in unison or in harmonies. In addition, Linda Oh herself would frequently use double-stops on her bass to create chords. When she soloed, Akinmusire would add long notes or punctuations to back her up like a piano paper might do.

Tommy Crane whose long hair covered his facial expressions for much of the evening proved himself a creative drummer in tune with the other musicians. He used the full arsenal of his small drum kit in a sensitive, albeit at times a bit busy way, alternating between the sticks and the brushes. From my vantage point sitting at the front slightly behind him, I could observe his dexterity and I in particular admired his use of the bass drum to accentuate the meandering music. The rhythms would move between free-flowing rubatos, straight rides and taut hi-hat beats (à la Jack de Johnette), often within the confines of the same song.

Linda Oh's pieces are tightly structured and written through, largely avoiding the traditional theme-solos-theme structure. It was a pleasure to observe the tiny cues—a slight nod or simple eye contact—that signaled the change of pace or mood or the entry of another theme to be played by the trumpet and the bass in between improvisational passages.

Ambrose Akinmusire played some of the most enjoyable and original solos of the evening. Much of the time, he played modestly, in low register, with a soft but broad tone reminiscent of a flugelhorn, only to burst into sparkling solos in a bright broad trumpet sound. His use of the horn's possibilities by way of tone and nuances was startlingly original and outright fun.

Apart from supplying the great material for the concert and leading the trio with a solid hand, Linda Oh also proved to be a bassist to be taken seriously. She has a fluid technique and beautiful natural sound. She used the whole range of the instrument reaching for the low tones above her head, while her solos and melodies often made her bend over to push the strings on the upper reaches of the fretboard.

Much of the repertoire this evening came from Linda Oh's first CD, Entry, which features her compositions for the trio (while Akinmusire plays the trumpet on the record, the drummer is different, Obed Calvaire), but the band did perform some new music as well. Her second CD, Initial Here, is scheduled to be released in May and features a different set up, this time with piano and saxophone, and on one sonhttp://www.blogger.com/img/blank.gifg another original performer with Asian roots, Jen Shyu. And on the new album we'll also hear Linda on the electric bass and bassoon, in addition to her big acoustic fiddle.

But this Friday evening we were treated to a varied set of acoustic trio pieces, such as the 'Morning Sunset', the rhythmically enticing 'Fourth Limb', the quietly beautiful 'Patterns', the complex 'Gunners', and the bopish uptempo crowd-pleaser '201'. When the concert was over and I left the hall, the party upstairs had picked up. The lounge was now full of people and a DJ was spinning records in one corner. I decided not to linger but stepped out into the rain on the 17th Street with a satisfied feeling about the state of music in the world.

Published on March 11, 2012 15:42

January 15, 2012

The Whale Warriors

The Whale Warriors: On Board a Pirate Ship in the Battle to Save the World's Largest Mammals by Peter Heller

The Whale Warriors: On Board a Pirate Ship in the Battle to Save the World's Largest Mammals by Peter HellerMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

As Japan is again continuing its whaling in the Antarctic waters against international law and the world's public opinion, this book describing the winter 2005-2006 campaign by Sea Shepherd is very timely. On January 9th this year, under the cover of darkness, three Australian Sea Shepherd activists managed to board the Japanese harpoon ship Shonan Maru No. 2 when it was just 26 km off the Australian west coast. The Japanese proceeded to arrest the environmentalists and took them to Tokyo, where a court released them without charges. The reason for the prompt release was probably that Japan does not want to draw undue attention to its controversial whaling activities.

Japan's insistence to go ahead with its extensive whaling is somewhat baffling. As Peter Heller demonstrates in his book, the government is forced to heavily subsidize the companies doing the whale hunt. There is very little demand for whale meat in Japan (only a tenth of the population confesses to ever eating it) and it has to be pushed on school lunch menus in some of the coastal areas with a high price to the tax payers. Tons of whale meat are piling up in freezers. Yet, more and more is brought in every year. Why? The officials cite traditional culture, but even that is a suspect argument. While some fishing communities, notably on the island of Shikoku, traditionally did hunt whales, this was limited to their coastal waters. Large scale commercial whaling only started when Japan built up its ocean going fleet after Commodore Perry's 'black ships' forced the opening of Japan to the outside world in 1854. The tradition certainly is not based in the ancient Japanese culture. The most likely explanation to the Japanese incalcitrance is nationalistic defiance against foreigners trying to tell them what to do. Sounds infantile? Well, it is, but it wouldn't be the first time.

Japan is a member of the International Whaling Commission (IWC), set up in 1946 "to provide for the proper conservation of whale stocks and thus make possible the orderly development of the whaling industry." IWC is thus not a conservation organization, but works for the long-term sustainability of the industry. So it can hardly be accused of sensationalizing the statistics. Yet, IWC recognizes that many whale species are endangered. On its website IWC acknowledges that many stocks of the thirteen species of 'great whales' have been depleted through over-exploitation. The authoritative Red List of endangered species compiled by the World Conservation Union identifies a number of whales as endangered. These include the Blue Whale, Fin Whale (Japan's self-set quota includes 50 Fin Whales per season), North Atlantic Right Whale and North Pacific Right Whale. In addition, a number of species are identified as threatened or vulnerable. Importantly, there is deficient data for most species to determine their status. Because of this state of affairs and the uncertainty about whale numbers, a moratorium on commercial whaling endorsed by IWC has been in place since 1986 (the UN Conference on Environment and Human Health originally proposed such a moratorium in 1972, but it was voted down by Japan, Russia, Iceland, Norway, South Africa and Panama).

As a response, Japan has circumvented the commercial whaling ban by claiming, quite disingenously, that its whaling program is for research purposes. This lethal research has been criticized by scientists and environmentalists alike. There are now non-lethal research methods that can be used to obtain the same data - and even if there were none, the large catch numbers could never be justified by the research argument. In IWC, a coalition led by by the USA, Canada, New Zealand and Australia has often challenged Japan for its "research" whaling. However, like in the UN, IWC operates on a one nation, one vote basis. Consequently, Japan has been able to purchase the votes of a number of tiny countries by providing them financial support. A number of Caribbean and Pacific Island countries - even the West Africa country of Togo - have voted in line with Japan in IWC following promises of official aid or even just covering travel and expenses of individual government officials. In all fairness, it must be said that there are also other countries that continue to kill whales, including Norway, Iceland, the Danish Faroe Islands and Russia.

When I was on the faculty of the UN University based in Tokyo in the early 1990s, I remember that we were approached by a consultant to the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries who proposed to pay for a study that we would conduct to show that whales were not endangered. During the meeting the gentleman got somewhat carried away and outlined a vision how whales could be domesticated to produce meat and milk for the growing human population. He further accused Western "meat eaters" for an emotional reaction to whaling. When I politely explained that we would gladly consider undertaking such a study, but that we would have to be in control of the study, select the research design and researchers, and that there could be no preagreed conclusions, he got up and promised to get back to us. Needless to say, he never did.

Adventure writer Peter Heller joined Sea Shepherd's ship Farley Mowat on a two-month expedition to the Antarctic in the 2005-2006 season to intercept the Japanese fleet. In 'The Whale Warriors' he provides an interesting and quite balanced account of the challenging trip during which the mostly volunteer crew under the command of Sea Shepherd founder Capt. Paul Watson searches, chases and engages with the Japanese fleet in the Antarctic waters. The book is written in a generally lively manner following the format of Heller's log of the days and weeks at sea, interspersed with information about the history of whaling, the Japanese whaling industry, ecology, the organizations that work against whaling (including Sea Shepherd and Greenpeace), and the international politics surrounding the issues. The format works well overall, but because of the lengthy search for the Japanese whalers and Heller's faithful depiction of the tedium at sea, the book feels a bit long (it could easily have been 50 pages shorter, I think). Even if the author's descriptions of the weather, the sea, the penguins, albatrosses and other sea birds, the icebergs, are beautiful, they also become somewhat repetitive. Finally, it is only on page 215 when the Farley Mowat first finds the location of the Japanese factory boat Nishin Maru and things start speeding up.

In the meantime, we meet the dedicated environmentalists from many countries (USA, Canada, Holland, Sweden, Brazil, South Africa, Australia, France) that make up the crew. These women and men form an interesting bunch, by no means homogenous in their philosophy, but all committed to saving the large, peaceful and highly intelligent animals. Heller observers exchanges that highlight the tensions between unexpected groups, such as between vegans and vegetarians or between conservationists and animal rights activists. His observations are often quite revealing and at best very funny. When the small helicopter onboard returns from a surveillance flight and performs a delicate landing on the deck of the ship rolling in heavy waves, Heller sees how the deck crew took only seconds to secure the landed chopper to the deck. "Pretty good for vegans with advanced degrees," he quips (page 267).

The book also sheds light on the continued rift between Sea Shepherd and Greenpeace. Paul Watson was one of the founders of Greenpeace and served as its Director from 1972 to 1977 when he left to found Sea Shepherd. He was growing frustrated with what he considered ineffective methods of Greenpeace, believing in a need for more direct action. The quartermaster of Farley Mowat on this trip is Emily Hunter, daughter of the Greenpeace co-founder and first President, the late Robert Hunter. Greenpeace manages to locate the Nishin Maru much before Sea Shepherd, but refuses to release the coordinates. The schism appears to be mostly with the top of the organizations and individual crew members of the Greenpeace ship Esperanza leak updates to Watson. As Farley Mowat finally sails to engage with Nishin Maru, Esperanza crew cheer it on. The trouble with Greenpeace non-confrontational tactics is that they only look on and document as the Japanese proceed to slaughter the whales in the most brutal and inhumane manner imaginable.

Whether the Sea Shepherd's more direct approach is any more effective is the question. As the Nishin Maru and its harpoon boats see Farley Mowat approaching they escape, only to move to another location to continue their hunt. Both organizations clearly have done much to bring the vicious and criminal activity to the forefront and thus influencing world opinion.

Yet, politics is what it is. Most of Japan's whaling takes place in the areas designated as off limits under the international moratorium and much in the territorial waters of other countries. Heller points out that if the whaling fleets were from less powerful developing countries, countries like Australia would not hesitate to intercept and arrest them in their territorial waters. Indeed, even earlier this week the Australian prime minister Julia Gillard criticized the Sea Shepherd activists for boarding the Shonan Maru, which was engaged in illegal activities in Australian territorial waters.

View all my reviews

Published on January 15, 2012 13:53

December 19, 2011

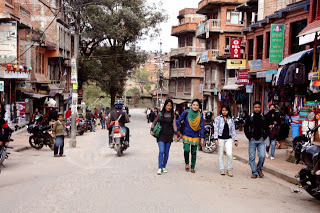

Kathmandu and Bhaktapur: Growth and Conservation

Kathmandu had changed in the 21 years I had not visited. The city had swelled with migrants from the countryside and was now home to more than 4 million people. In the meantime, the valley in the Himalayan foothills where the city is located had not miraculously expanded. Consequently, the place was now crowded. It was no longer the quaint village-like old town it had been in the late-1980s and early-1990s when I used to come here. On my first morning back, I went to the New Road area in the center of the city. Most of the buildings were still the same old ones, now distinctly rundown, although new commercial buildings with glass walls that reflected the scenery and shiny malls had sprung up here and there. The Chinese center looked particularly impressive. The leisurely pace was gone and the place was bustling with people hurrying to get wherever it was they were going. There were peasant looking women and men carrying huge loads on their backs and heads, their sun-drenched faces lined and leathery making them look old (although many were probably younger than me). Women wearing colorful saris mingled with young people dressed in jeans. A couple of farmer women sat on the pavement selling fruit from baskets amidst the busy pedestrians.

Most obviously, there was the traffic. Where there had been lots of bicycles and few cars, the bikes were now almost gone—I only saw one pedicab that morning—and cars, motorbikes and scooters ruled the streets. A lone traffic police stood on the pedestal of a status at an intersection trying to create order in the chaos. The officer's mouth and nose were covered with a cloth mask, wisely, as the exhaust fumes would choke anyone standing in the middle for any length of time. The driver from our office who had taken me downtown had things to say about the traffic and the pollution. "These people are from the rural areas. They have never lived in the city and don't know anything about traffic rules, nor did they ever learn to drive in the first place," he lamented. As we waited at another junction where another officer, this time a woman, made valiant efforts to directing the crowds, the driver had a long story about futile efforts to control air pollution that had been in place for the better part of the past decade. The bottom line seemed to be that the government did not want to enforce the rules, as it would have meant replacing all the official vehicles that the city nor the national government could never afford. Consequently, everyone continued to use the noisy motorbikes and old cars without catalyzers, and the antique buses continued to belch thick smoke into the mountain air. It's not that there were no new cars, as well, just that these had been added to the existing fleet of ancient vehicles.

Even under normal circumstances, developing country cities grow at breakneck speeds. People move to the cities for the economic opportunities that exist in them, even if it means living in a slum. At the same time, they continue to have many children, as if from an old habit, although the children in the city no longer provide the same useful workforce they were on the farm. With improved healthcare, sanitation and nutrition, child mortality has decreased and more children survive. All this contributes to a huge boost in city sizes. Now more than half of the world's population lives in cities, many of them enormous mega-cities. Out of the 10 largest cities in the world, 6 are now in the developing countries (and 7 in Asia).

Kathmandu's growth was still a special case. A long-lasting Maoist rebellion had chased people away from the countryside. Originally, the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) declared an armed rebellion on February 13, 1996, with the objective of establishing a communist state. The Maoists opposing what admittedly was rather a feudal system prevailing in Nepal terrorized people for a decade. There were forced 'land reforms,' whereby poor farmers lost their lands to collectivization, and plenty of violence against perceived enemies of the revolution, as well as between the Maoists and the government forces. Many people died during the conflict. At the same time, as so often happens, some revolutionaries descended into criminality, while criminals saw the opportunity to make money by pretending to be revolutionaries (think of similar cases in, say, Colombia or the southern islands of the Philippines). Kidnappings for ransom became common and the victims often got killed by the bandits whether their family or company paid up or not. In the Terai region in the south, gangs would haul their victims across the border to India not to be seen again. The situation only changed when a comprehensive peace accord was signed on November 21, 2006, which allowed the Maoists to join the transitional government. While they later emerged as the largest party in the Constituent Assembly, they never gained the majority. Instability in Nepalese politics has continued.

The purpose of my trip related to an evaluation my office had conducted about UNDP's contributions to national development results in Nepal over the past 8 years. These had been particularly turbulent years in the history of the country. Apart from the internal conflict that had peaked during the period, an extraordinary event had added to the extreme political turmoil. On June 1, 2001, Crown Prince Dipendra in an alcohol fueled craze shot and killed nine members of the royal family, including his own father King Birendra and mother Queen Aiswarya. It is said he was mad at his parents for opposing his marriage to a girl from a rival family. The revered royal family had been virtually the only institution that had kept the kingdom together. Following the regicide, a new king, Gyanendra, was crowned. This signaled the beginning of the end of the monarchy. Gyanendra dissolved the parliament and suspended elections indefinitely in 2002 following the failure of peace talks with the rebels. The state of emergency was lifted only in April 2005 under international pressure and the parliament was finally reinstated a year later. Immediately afterwards, the newly established parliament, quite understandably, voted unanimously to curtail the king's political powers. In December 2007, the parliament voted to abolish the monarchy altogether and the constituent assembly declared Nepal a republic on May 28, 2008.

During this period, UNDP had done its best to support post-conflict recovery and a transition to democracy. Things were peaceful now and Nepal had been turned into a parliamentary democracy (with the Maoists learning to play by the rules in the parliament) with an emerging federal structure. Local elections had not yet been held—the security situation did not yet allow for it and there was too much uncertainty in the government—and consequently appointed local officials did not feel accountable to the electorate. We heard lots of complaints about rampant corruption in the rural areas.

One afternoon I had free time and joined one of our local consultants, Kanta Singh, who had promised to take our South African consultant Angela Bester to visit Bhaktapur, a World Heritage Site just half an hour's drive to the east from Kathmandu. Half an hour, that is, without traffic. Including the driver, we were four people crammed into the tiny Hyundai as we hit the traffic. We started in Lalitpur, a peaceful neighborhood of small streets on a hill where I was staying, and headed across the city. The road towards the airport was being widened. For already two decades, apparently, there had been a ban to construct buildings within a certain limit from the existing road because of the eventual plans to widen the road. However, people had ignored it and now, finally, when the road project was underway, the authorities were in the business of leveling illegally constructed houses. We passed official buildings heavily guarded by police in camouflage uniforms and riot gear armed with guns and long sticks. The congestion got worse before we reached the city limits. In one spot, hundreds of small vans and buses transporting people seemed to stop to let off their passengers and to attract more, thus creating a near standstill. The road passed just below the landing route to the airport and several planes appeared to be heading straight towards us only to roar past almost touching the rooftops.

Once we hit the highway towards Bhaktapur, the traffic eased and our car picked up speed. "Ten years ago, this was an agricultural area and we came here to get our vegetables directly from the farmers," Kanta explained. Now the entire road was lined with new construction, buildings of up to 5 stories high. In between there were still small patches of agriculture. Rice paddies could be seen on the slopes leading to small creeks. What struck me was how shoddy the construction looked. Most buildings seemed to consist of red bricks piled up on top of each other, often in a seemingly haphazard way. Nepal did have a building code, according to Kanta, but nobody really enforced it. Sitting on the edge of the Indian and Eurasian plates, this was earthquake country and I suspected most of the new buildings would not stand a chance if a big one hit the area.

Bhaktapur, just 13 km east of the modern capital, is considered the cultural capital of Nepal. It has been restored with technical cooperation from Germany and is recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. Originally an agricultural market and artisan town, its history can be traced back to the 7th century C.E. It is built on a hill with narrow winding roads. According to tourist information, it is "geographically shaped as a conch-shell and geometrically designed into the Tantric fabric shaped Shree Yantra." I take them at their word on this. Suffice it to say that the city is lovely and wonderfully preserved. It is still a perfectly living piece of history. The artisanal legacy of bronze-casting, carving, masonry, painting and other crafts lives on, while much of the economy seems to have turned to the tourist industry, with numerous small shops lining the streets. As we headed towards the Durbar Square in the middle of the town, we met with a wedding celebration. The proceeding was headed by a brass band that was blowing away with abandon, the trumpeters, other horn players and drummers dressed snappily in red jackets. Old men and women carried traditional items and candles in front of the small car wrapped in celebratory decorations that was carrying the wedding couple. The guests—men dressed in Western suits, women in gorgeous saris of deep red, yellow, green and gold—followed behind on foot.

Separating ourselves from the celebrators, we explored Bhaktapur on foot for the next 3 hours. Here in the town between the fabulous squares, like the Durbar, Taumadhi and Dattatreya Squares, that housed all the incredible temples and palaces, regular people lived. Their houses were old and many still not renovated. We could see signs from old earthquakes that had bent and twisted old brick walls into odd shapes. Even the amazing five centuries old Fifty-Five Windows Palace was badly damaged in the powerful 1934 earthquake. A beautiful little girl was leaning against the wall of her house—several stories high—that had cracked so badly that the residents had erected a pole in the adjacent alley to prevent the side wall of the building from collapsing.

One of the beauties of Bhaktapur and Nepal in general is how for hundreds of years Buddhism and Hinduism have existed peacefully side by side. Bhaktapur has temples for both religions, but sometimes they seem so mixed that it is hard to say which religion they really belong to. I suppose the correct—and most beautiful—answer would be: they belong to both. On another morning when we had a few hours of free time between appointments, Angela and I walked over to Patan Square, another restored World Heritage Site in Lalitpur. In its museum I again reflected with fascination upon the intermingling of the Buddhist and Hindu traditions. Not only were they practiced side by side, their very deities and sacred texts were intertwined. (Similarly in Japan, where it is said 90% of the people are Shintoist and 80% are Buddhist, religions—or perhaps more correctly traditions—coexist. One cannot help wonder what it is with these Middle Eastern religions—Judaism, Christianity and Islam—that makes them so intolerant of what each sect perceives as the only correct orthodoxy.)

We had a good guide in Kanta's driver whose home was close by and he was quite familiar with Bhaktapur and could show us out of the way attractions. At one point he led us through a small porch leading to a tiny inner yard in between residential buildings. The yard contained a small Hindu temple with an altar for sacrifices attached to it. The altar and the ground beneath it were splattered with the red of the blood of the chicken and goats that had been slaughtered there. A beautiful black cat with a shiny fur presided over the square languidly strolling around, ignoring us.

One of the interesting parts of the walking tour was to observe how the old social mores still prevailed. Kanta showed us a number of water wells, which were traditionally social gathering points for women. A particularly large one was protected by a statue of a cobra, with a serpentine carving surrounding it. The water points could be found in many places of the city and it was clear they still served a social function for the women. The men stuck to themselves and when the afternoon advanced one could see pairs and groups of them sitting around the squares, often on the steps leading to temples or palaces making them part of the everyday life of the town dwellers.

I wanted to buy some good Nepali tea, which is similar to but less well known than Darjeeling (some tea connoisseurs even consider the Nepali variety to be superior to the Indian). I was guided to a small store kept by a sweet and rather sophisticated young couple. On the wall there was a snapshot of the couple in Paris where they had gone for their honeymoon. They showed me the various varieties from the most highly priced white-tipped tea. My goal was to settle for the second flush, which is harvested in the season between May and July, and has a lush mellow taste.

While inspecting the teas, I couldn't help getting carried away by the lovely flute music coming from the stereo. I asked the husband about it and he explained it to be traditional Nepali music. The band, Kutumba, plays traditional Nepali tunes and instruments—flutes, strings, drums and bells—in an improvisatory style. When we had established that I was particularly fond of Asian flute music, he introduced me to a contemporary version by Kala Chakra, which was now popular in Nepal. "Lounge," I suggested as we sampled the music; "Fusion," corrected the owner. Either way, the music captured the tradition in a contemporary electronic, yet lovely manner. Later in the evening, beautiful flute sounds again drifted to my ears. It turned out that there was another wedding procession that had made a more traditional musical choice, with a band of young people playing the bamboo flutes from the region.

By the time we returned to Kathmandu, the night had fallen and with no streetlights it was pitch dark. The driver decided to take a shortcut through Patan. Its narrow streets were full of people, cars, motorbikes, dogs, an occasional goat. Three-wheeled motorized rickshaws, here called 'Tempu' and larger than the famous Tuk-Tuks of Bangkok, were cruising the streets and abruptly stopping for passengers. Our tiny Hyundai zipped in between buildings, people and vehicles, filling any small space that would open up. At times we got stuck for a minute or two as a truck or a larger vehicle would come from the other direction (luckily, most of the cars in Kathmandu are small). Then again the driver would accelerate to what I considered a dangerous speed when he'd see an opening. Horns were blaring all around us as every user of the road employed the same strategy of advancement. On several occasions I was certain that we'd hit a lady waddling on the side in a sari, or a family walking in a group as if they had all the space in the world, but nothing happened. It was just me who was not used to the going.

Finally we reached Lalitpur and our hotel, a veritable sanctuary so close to the madness of the commercial city. The dry air had been so saturated with dust that I noticed my throat was parched. That was helped by a cold Everest beer before washing off the dirt in a hot shower. Somehow despite its uncontrollable growth and seeming chaos, Kathmandu has maintained its charm and humanity. Efforts to restore and renovate old towns like Bhaktapur and Patan are important beyond their value as repositories of history and culture, as they are attractions that bring much needed income to the country. The fact that both are also living environments where people lead their lives is a highly positive aspect. The harmony that exists between the Buddhist and Hindu traditions should serve as an example for many other places.

Upon my return home, I rummaged through my bookshelf for some old books about Nepal to revisit how the country was described just two decades or so ago. (In the dust jacket of one, Nepal: Socio-Economic Change and Rural Migration by Poona Thapa, I discovered the invoice from Ratna Pustak Bhandar booksellers in Kathmandu where I had purchased the book on May 16, 1990, for Rp. 327.60.) One striking figure was that in 1991, Kathmandu had had a population of just 421,000, indicating that the city had actually grown ten-fold since then. But even before that, the growth had been tremendous, as the 1981 data showed a population of only 235,000 for the city! Many issues that were highlighted by the older publications are still valid concerns: poverty, major inequalities between regions, heavy internal migration. Despite these challenges, much progress has been made, especially since the worst of the political troubles have calmed down. Measured on the UN Human Development Index, Nepal is still on the 138th place amongst the 169 countries included, but its rating is constantly and rapidly rising. One must hope that this trend will continue. Much will depend on the continued political stability, peace and security in the country.

Published on December 19, 2011 16:05

December 5, 2011

The Lunatic Express by Carl HoffmanMy rating: 4 of 5 star...

The Lunatic Express by Carl Hoffman

The Lunatic Express by Carl HoffmanMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

This is a travel book focusing on modes of transportation that most travellers would prefer to avoid. Carl Hoffman's stated desire was to circumnavigate the globe on the cheapest and most dangerous forms of mass transit. For most of humankind, travel was no pleasurable touring, but a necessary movement from point A to point B often involving terribly long and uncomfortable, not to mention perilous, trips on decrepit buses that would plunge into gorges from the winding mountainside roads that they travelled, on overcrowded, capsizing ferries, unmaintained ancient aircraft, and trains that were so stuffed with people that they just fell off on the tracks. Hoffman's travels over several months involved all of the above, as he left his home in Washington, DC, and toured around the Andes and Amazon basin in South America, the roads and railroads of East and West Africa, the notorious deathtraps that ferries in Indonesia and Bangladesh were. He had weeks of relative leisure in India before flying to Afghanistan on the national airline Ariana (a.k.a. Scariana). Then returning home by train and gas truck through China, Mongolia and Siberia. Through all these segments of travel he reports on the exotic places he encounters, the hairy situations arising and, most importantly, the various people he meets.

Carl Hoffman is plagued by wanderlust. He is middle-aged, married with three kids, a journalist, but for a long time he has felt compelled to leave the comforts of home behind and travel. This is the other theme of the book: man's struggle between loneliness and belonging. The book gets quite personal, as Hoffman misses his family while at the same time feels alive only travelling in risky places amongst strange people. At times his descriptions of his own addiction to danger seem slightly too heroic, but at least I personally can very well relate to his contradictory feelings. He observes with some envy people in the poor countries that he visits and interacts with, how they all have strong bonds in their communities and families; at the same time, he knows that he could never live that way, with no privacy or time alone. When he finally is returning home, he notes that he was settling in and getting a little bored on the trip. He concludes that it was time to go home: "Travel was only worthwhile when your eyes were fresh, when it surprised you and amazed you and made you think about yourself in a new way. You couldn't travel forever. When you stopped seeing, when you lost your curiosity and openness to the world, it was time to return to your starting point and see where you stood" (p. 263).

I found the book to be well worth reading, well written, even quite wise. Although the narrative was generally entertaining, I found there was a certain unevenness to the chapters (probably reflecting the interestingness of the segment and the people Hoffman happened to meet). The cover of my edition touted it as a "Wall Street Journal Book of the Year." I wouldn't go that far and the accolade baffled me initially, before I realized that for an average WJS reader the book would cover territory that was strange and likely unsightly. The Lunatic Express certainly serves its purpose as an antidote to seeing travel only through the lens of comfortable business travel or relaxing tourism. Carl Hoffman made a superb effort to experience travel the way the majority of the world's people experience it. In the process he met numerous interesting and hospitable people whom he recalls frequently with warmth, always with understanding.

View all my reviews

Published on December 05, 2011 20:45

October 23, 2011

A Week (or Two) in Music: Only in New York

It's been a New York week—well, I guess every week is like this in New York. Actually, I only listened to three live performances, although there'd be something worthwhile to hear every night and I in fact had noted a couple of more possible concerts in my calendar. That's what I do: I scan the opportunities to listen to some interesting music in advance and mark them in my Google calendar, so that I won't forget about them or won't be at a loss if one evening I just feel like catching some act. The reason why I thought of jotting down this week's crop is because the three acts were all quite different from each other but represented broad categories of music that are all close to my heart. All were also played in quite intimate settings and mostly with acoustic instruments.

First, on Tuesday night (October 4), there was a duo performance by two of my favourite instrumentalists at the Living Room in Manhattan's Lower East Side. As it happens, I also know both Oran Etkin and Ben Allison personally and they are both the nicest boys in the business. What I didn't know is that they played together—and apparently it is a perfectly new thing. Their performance was part of celebrating the Independent Music Awards—Oran had just won the 'Best World Beat' award for his album Kelenia—and there was a succession of winning bands at this bar-cum-performance space. Oran and Ben had a half hour slot in the middle of the evening, which they filled with three pieces of fantastic communication with acoustic wooden instruments. All compositions were Etkin originals, starting with the hypnotic Kelenia from his African music project. This time played only on bass clarinet and contrabass, the tune produced a wonderful atmosphere with its ostinato-like theme. This was followed by Wake Up, Clarinet!, an entertaining number from Oran's popular children's album. It's easy to see why kids would find it irresistibly fun when the cheerful bearded guy has a great time communing with his clarinet. The duo's last piece was Lacy—dedicated to the soprano saxophone innovator Steve Lacy—a quirky jazz tune in which the musicians' interplay was again seamless, with Ben providing a solid basis for the music as he pulled double stops on his bass.

[image error]

(Exceptionally, these pictures are not mine, but by Yoko Takahashi, so that I could get into the photo with the guys.)

The following night I headed to the City Winery to catch a concert with Bebel Gilberto, the famous contemporary Brazilian singer. The star spent last summer as artist in residence at City Winery and performed several sold-out concerts. I only managed to get my act together and buy a ticket to the last extra one organized as an in August due to high demand. Alas, the concert was rescheduled due to the rare Hurricane Irene that hit New York just on the evening when Gilberto was supposed to perform. It thus took more than a month to organize the concert until Wednesday, October 5. In August, the extra concert was supposed to be an intimate evening only with the songstress and an acoustic guitarist. When I entered the crowded hall on this Wednesday evening, it was clear we would be now treated to the full band. There was a drum set, keyboards and amplifiers on stage. There was tangible electricity in the air—and the audience would not be disappointed. The diva, dressed in a tight black dress, was at her best, chatting with the audience in between the tunes, with a glass of wine constantly at her side. The daughter of legendary Brazilian musicians, Joao Gilberto and Miúcha, Bebel carries the torch of the bossa nova tradition that her parents were amongst the core group creating. Despite the five-piece band, the music remained very intimate and the volume at a very moderate level. She performed a long set consisting of hits from her own albums as well as a number of older songs. Personally, I was most taken by Jorge Continentino, whose alto flute provided an atmospheric ambience to most of the songs. On one tune, he switched to a horizontal bamboo flute, which he handled very nicely and entirely in tune (not always so easy with a bamboo flute). There was also a trombone in the band, which together with the alto flute produced a pleasant mellow addition to the music. At one point of the evening, Bebel asked an audience member to pass a candle from the table to her. Then she started the birthday song, approached the trombonist for a hug and passed the candle on to him. The birthday boy was so moved that he started to weep. "More than 20 years of friendship," Bebel declared to the audience. Clearly, the star has a faithful relationship with her musicians. We were allowed to witness some intimate moments of her singing accompanied only by Bebel's long-term guitarist, Masa Shimizu. On some of the later pieces of the evening, the tempos increased. Continentino switched his small pipes to a large curved baritone sax with which he joined in funky riffs with the trombonist. All in all, a superb concert.

Then, on Sunday, Yoko and I headed to one of our favourite Sunday afternoon places, the Noguchi Museum in Queens. The afternoon Music in the Garden promised shakuhachi music with Elizabeth Brown. We couldn't have been luckier, as after a cool spell of autumn weather New York was experiencing Indian summer. We sat out in the garden with some 50 other listeners enjoying a most beautiful sunny afternoon amongst Isamu Noguchi's sculptures and the verdant trees. Elizabeth Brown is an award winning composer and performer on the shakuhachi, the western flute and theremin. She took her place under a large aspen whose leaves had already turned largely bright yellow. Her set alternated traditional shakuchachi honkyoku—Oshu Sashi and Sokaku Reibo—with her own compositions, Hermit Thrush (1991) and From Isle Royale (2005). Her own pieces combine contemporary music aspects with traditional Japanese tonalities. Both pieces were inspired by the sounds of birds she had listened to while composing the music in the middle of nature. Here, the meditative sounds of shakuhachi mixed with the more urban soundscape of the inevitable helicopters and cars crossing Queens. For the last piece, Shika no Tone—another honkyoku tune in Kinko-ryu style—Elizabeth Brown called Ralph Samuelson to join her. She introduced Ralph "her mentor, teacher and friend." The two flutists moved to the opposite sides of the garden creating a lovely echo mimicking the distant cry of the deer that the tune's title implies. Moving slowly closer to each other, the stereo effect created by the two shakuhachis was purely lovely.

[image error]

Originally, I had intended to just describe these three exquisite concerts in such disparate styles and venues all played during the same week in this city—hence the title of this blog. But as I failed to complete writing this in time, I feel compelled to add to the mix. On the following Sunday, October 16th, we took our friend Masako, visiting from Tokyo, to Le Poisson Rouge to listen to a piano recital by Peter Hill. The concert was constructed around the music of Olivier Messiaen, whose premier interpreter the British pianist is. He made a smart strategic move by starting the modern concert with J.S. Bach, making the connections that both Bach and Messiaen were organists and both also superb improvisers. The beautiful start served its purpose of focusing the attention of the audience in the concert venue that doubles up as a restaurant. The rest of the evening consisted of pieces by Messiaen, with the exception of one piece by Toru Takemitsu composed in memoriam of the French composer. The highly sympathetic Peter Hill explained that he had selected the program around Messiaen's compositions inspired by birdsong (something in common with Elizabeth Brown's shakuhachi music!), starting with La Colombe that Messiaen had written in 1926 when he was just 18. Later pieces from the 1950s and Cantéyodjayâ that Messiaen composed while in Tanglewood in 1949 demonstrated how his musical language had evolved. The last number was lovely, contrasting the dark night when the composer had been driving in France with his wife, with the competing coloratura of a pair of larks and a nightingale they had observed. Messiaen was an accomplished ornithologist who incorporated birdsong systematically in his music. I was absolutely delighted to have decided to come to the concert. Messiaen's music was not very familiar to me and this recital, enhanced with Peter Hill's commentary, truly opened up his music to me. As an encore, Hill played a piece that Messiaen had written as a sight reading exercise for his students. Apparently, the master had written many such exercises but this was the only one that had survived—a tragedy of 20th century music, as recounted by Hill.

[image error]

Then finally, on Tuesday, October 18th, Masako's last night in New York, she and I went to the Jazz Standard while Yoko was rehearsing for her own forthcoming performance. The work we heard was Race Riot Suite composed by Chris Combs and performed by the Jacob Fred Jazz Odyssey. The lengthy suite in 12 parts turned out to be an incredible tour de force by both the composer and the orchestra. I had picked the show only based on the description, which explained that the suite had been composed to tell the story of the evolution and destruction of Greenwood, a highly successful African-American neighbourhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma (the centre of Greenwood was known as the "Black Wall Street"). On May 31, 1921, in an occurrence of exceptional racial conflict, white mobs invaded Greenwood and as a result at least 40 people were killed and over 800 were hospitalized. Some 35 city blocks were destroyed by fire and an estimated 10,000 people were left homeless. The all-white Jacob Fred Jazz Odyssey hails from Tulsa and consists normally of four musicians: Brian Haas, Josh Raymer, Chris Combs and Jeff Harshbarger. A unique feature of the band is that to the normal piano trio is added a lap steel guitar played by Combs, the writer of the Race Riot Suite. For performing the Suite, the band was strengthened by three horn players: Steven Bernstein (trumpet and slide trumpet), Mark Southerland (tenor and soprano saxes) and Peter Apfelbaum (tenor and baritone saxophones). This was one of the best and most innovative pieces of new jazz music that I have heard in a long while. The composition builds upon a long tradition of New Orleans jazz and ragtime and contains clear nods towards the great composers and band leaders, such as Duke Ellington and Charles Mingus. The expression is contemporary and the harmonies very interesting, with the steel guitar's wails often blending in with the horns. Every player contributed wonderful solos throughout the music, so I would just highlight a couple that stayed with me. Overall, I loved Apfelbaum's work on both of his saxes. The tenor was exceptional warm (and contrasted well with Southerland's stormier approach) and there was an interesting moment when the baritone soloed only against Haas' piano accompaniment (and what a rare treat it was to hear a second excellent baritone player in just two weeks!). Overall, Haas provided some entertaining piano playing, while Bernstein's trumpet channelled Roy Eldridge and Cootie Williams transported into the 21st century. Harshbarger and Raymer on bass and drums soloed less, but ensured that there was a solid rhythmic structure—at times chaotic, but always firmly rooted—to this complex music. This was programmatic music at its best.

First, on Tuesday night (October 4), there was a duo performance by two of my favourite instrumentalists at the Living Room in Manhattan's Lower East Side. As it happens, I also know both Oran Etkin and Ben Allison personally and they are both the nicest boys in the business. What I didn't know is that they played together—and apparently it is a perfectly new thing. Their performance was part of celebrating the Independent Music Awards—Oran had just won the 'Best World Beat' award for his album Kelenia—and there was a succession of winning bands at this bar-cum-performance space. Oran and Ben had a half hour slot in the middle of the evening, which they filled with three pieces of fantastic communication with acoustic wooden instruments. All compositions were Etkin originals, starting with the hypnotic Kelenia from his African music project. This time played only on bass clarinet and contrabass, the tune produced a wonderful atmosphere with its ostinato-like theme. This was followed by Wake Up, Clarinet!, an entertaining number from Oran's popular children's album. It's easy to see why kids would find it irresistibly fun when the cheerful bearded guy has a great time communing with his clarinet. The duo's last piece was Lacy—dedicated to the soprano saxophone innovator Steve Lacy—a quirky jazz tune in which the musicians' interplay was again seamless, with Ben providing a solid basis for the music as he pulled double stops on his bass.

[image error]

(Exceptionally, these pictures are not mine, but by Yoko Takahashi, so that I could get into the photo with the guys.)

The following night I headed to the City Winery to catch a concert with Bebel Gilberto, the famous contemporary Brazilian singer. The star spent last summer as artist in residence at City Winery and performed several sold-out concerts. I only managed to get my act together and buy a ticket to the last extra one organized as an in August due to high demand. Alas, the concert was rescheduled due to the rare Hurricane Irene that hit New York just on the evening when Gilberto was supposed to perform. It thus took more than a month to organize the concert until Wednesday, October 5. In August, the extra concert was supposed to be an intimate evening only with the songstress and an acoustic guitarist. When I entered the crowded hall on this Wednesday evening, it was clear we would be now treated to the full band. There was a drum set, keyboards and amplifiers on stage. There was tangible electricity in the air—and the audience would not be disappointed. The diva, dressed in a tight black dress, was at her best, chatting with the audience in between the tunes, with a glass of wine constantly at her side. The daughter of legendary Brazilian musicians, Joao Gilberto and Miúcha, Bebel carries the torch of the bossa nova tradition that her parents were amongst the core group creating. Despite the five-piece band, the music remained very intimate and the volume at a very moderate level. She performed a long set consisting of hits from her own albums as well as a number of older songs. Personally, I was most taken by Jorge Continentino, whose alto flute provided an atmospheric ambience to most of the songs. On one tune, he switched to a horizontal bamboo flute, which he handled very nicely and entirely in tune (not always so easy with a bamboo flute). There was also a trombone in the band, which together with the alto flute produced a pleasant mellow addition to the music. At one point of the evening, Bebel asked an audience member to pass a candle from the table to her. Then she started the birthday song, approached the trombonist for a hug and passed the candle on to him. The birthday boy was so moved that he started to weep. "More than 20 years of friendship," Bebel declared to the audience. Clearly, the star has a faithful relationship with her musicians. We were allowed to witness some intimate moments of her singing accompanied only by Bebel's long-term guitarist, Masa Shimizu. On some of the later pieces of the evening, the tempos increased. Continentino switched his small pipes to a large curved baritone sax with which he joined in funky riffs with the trombonist. All in all, a superb concert.

Then, on Sunday, Yoko and I headed to one of our favourite Sunday afternoon places, the Noguchi Museum in Queens. The afternoon Music in the Garden promised shakuhachi music with Elizabeth Brown. We couldn't have been luckier, as after a cool spell of autumn weather New York was experiencing Indian summer. We sat out in the garden with some 50 other listeners enjoying a most beautiful sunny afternoon amongst Isamu Noguchi's sculptures and the verdant trees. Elizabeth Brown is an award winning composer and performer on the shakuhachi, the western flute and theremin. She took her place under a large aspen whose leaves had already turned largely bright yellow. Her set alternated traditional shakuchachi honkyoku—Oshu Sashi and Sokaku Reibo—with her own compositions, Hermit Thrush (1991) and From Isle Royale (2005). Her own pieces combine contemporary music aspects with traditional Japanese tonalities. Both pieces were inspired by the sounds of birds she had listened to while composing the music in the middle of nature. Here, the meditative sounds of shakuhachi mixed with the more urban soundscape of the inevitable helicopters and cars crossing Queens. For the last piece, Shika no Tone—another honkyoku tune in Kinko-ryu style—Elizabeth Brown called Ralph Samuelson to join her. She introduced Ralph "her mentor, teacher and friend." The two flutists moved to the opposite sides of the garden creating a lovely echo mimicking the distant cry of the deer that the tune's title implies. Moving slowly closer to each other, the stereo effect created by the two shakuhachis was purely lovely.

[image error]

Originally, I had intended to just describe these three exquisite concerts in such disparate styles and venues all played during the same week in this city—hence the title of this blog. But as I failed to complete writing this in time, I feel compelled to add to the mix. On the following Sunday, October 16th, we took our friend Masako, visiting from Tokyo, to Le Poisson Rouge to listen to a piano recital by Peter Hill. The concert was constructed around the music of Olivier Messiaen, whose premier interpreter the British pianist is. He made a smart strategic move by starting the modern concert with J.S. Bach, making the connections that both Bach and Messiaen were organists and both also superb improvisers. The beautiful start served its purpose of focusing the attention of the audience in the concert venue that doubles up as a restaurant. The rest of the evening consisted of pieces by Messiaen, with the exception of one piece by Toru Takemitsu composed in memoriam of the French composer. The highly sympathetic Peter Hill explained that he had selected the program around Messiaen's compositions inspired by birdsong (something in common with Elizabeth Brown's shakuhachi music!), starting with La Colombe that Messiaen had written in 1926 when he was just 18. Later pieces from the 1950s and Cantéyodjayâ that Messiaen composed while in Tanglewood in 1949 demonstrated how his musical language had evolved. The last number was lovely, contrasting the dark night when the composer had been driving in France with his wife, with the competing coloratura of a pair of larks and a nightingale they had observed. Messiaen was an accomplished ornithologist who incorporated birdsong systematically in his music. I was absolutely delighted to have decided to come to the concert. Messiaen's music was not very familiar to me and this recital, enhanced with Peter Hill's commentary, truly opened up his music to me. As an encore, Hill played a piece that Messiaen had written as a sight reading exercise for his students. Apparently, the master had written many such exercises but this was the only one that had survived—a tragedy of 20th century music, as recounted by Hill.

[image error]

Then finally, on Tuesday, October 18th, Masako's last night in New York, she and I went to the Jazz Standard while Yoko was rehearsing for her own forthcoming performance. The work we heard was Race Riot Suite composed by Chris Combs and performed by the Jacob Fred Jazz Odyssey. The lengthy suite in 12 parts turned out to be an incredible tour de force by both the composer and the orchestra. I had picked the show only based on the description, which explained that the suite had been composed to tell the story of the evolution and destruction of Greenwood, a highly successful African-American neighbourhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma (the centre of Greenwood was known as the "Black Wall Street"). On May 31, 1921, in an occurrence of exceptional racial conflict, white mobs invaded Greenwood and as a result at least 40 people were killed and over 800 were hospitalized. Some 35 city blocks were destroyed by fire and an estimated 10,000 people were left homeless. The all-white Jacob Fred Jazz Odyssey hails from Tulsa and consists normally of four musicians: Brian Haas, Josh Raymer, Chris Combs and Jeff Harshbarger. A unique feature of the band is that to the normal piano trio is added a lap steel guitar played by Combs, the writer of the Race Riot Suite. For performing the Suite, the band was strengthened by three horn players: Steven Bernstein (trumpet and slide trumpet), Mark Southerland (tenor and soprano saxes) and Peter Apfelbaum (tenor and baritone saxophones). This was one of the best and most innovative pieces of new jazz music that I have heard in a long while. The composition builds upon a long tradition of New Orleans jazz and ragtime and contains clear nods towards the great composers and band leaders, such as Duke Ellington and Charles Mingus. The expression is contemporary and the harmonies very interesting, with the steel guitar's wails often blending in with the horns. Every player contributed wonderful solos throughout the music, so I would just highlight a couple that stayed with me. Overall, I loved Apfelbaum's work on both of his saxes. The tenor was exceptional warm (and contrasted well with Southerland's stormier approach) and there was an interesting moment when the baritone soloed only against Haas' piano accompaniment (and what a rare treat it was to hear a second excellent baritone player in just two weeks!). Overall, Haas provided some entertaining piano playing, while Bernstein's trumpet channelled Roy Eldridge and Cootie Williams transported into the 21st century. Harshbarger and Raymer on bass and drums soloed less, but ensured that there was a solid rhythmic structure—at times chaotic, but always firmly rooted—to this complex music. This was programmatic music at its best.

Published on October 23, 2011 10:54

October 2, 2011

Sikkim Earthquake, 18 September 2011

On Sunday, just when I had arrived, there was an earthquake. It didn't really register with me. Delhi shook gently, enough for many others to notice, but I was jetlagged and went to sleep. My colleague Gus thought he was suddenly feeling the symptoms of old age as dizziness set in and he had to sit down on the sofa, he told me afterwards.

What had taken place was an earthquake with an epicentre in Sikkim, hundreds of kilometres away from the national capital region. The quake hit the Sikkim-Nepal border area at 18:10 hours near the boundary between India and Eurasia plates. It was 6.8 on the Richter Scale and, given the style of construction and rough hilly terrain, it would turn out to be the most destructive earthquake to hit India in ten years. People rushed out of the houses that started to collapse. In addition, there were reports of extensive landslides and downed power lines. "Tremors were felt between 30 seconds to one minute in some parts of Sikkim, including Gangtok," the State capital, said Shalesh Nayak, Secretary in the Indian Earth Sciences Ministry, said according to The Times of India (19 September 2011). Nearly everyone in Sikkim and Darjeeling spent Sunday night in the open as aftershocks triggered fears of a second wave of destruction.

Sikkim is a Himalayan state in the Indian northeast, bordered by Nepal to the west, Tibet (China) to the north and Bhutan to the east. Its southern border is with the Indian state of West Bengal. The mountainous State is quite sparsely populated—according to the latest 2001 census, the total population was only 540,000 people—and only 11% of the people live in urban areas. "Sikkim is sheer magic," gushes the State's official website. "This is not just the most beautiful place in the world but cleanest and safest too," it continues. This pristine idyll was shattered by the quake.

Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh called Sikkim's Chief Minister Pawan Kumar Chamling, who reportedly described the damage as serious. Early reports confirmed 15 dead in Sikkim and across the border in Nepal, but the death toll would keep on rising. By the following Saturday, 24th of September, there were reportedly 75 dead and more than 61,000 left homeless in Sikkim alone. In addition, 10 people were reported dead in Bengal and 7 in Bihar. And the rescue crews had not yet reached the most remote areas due to landslides and heavy rains.

On Tuesday, 20 September, The Times reported that virtually nothing was left intact on the 100 km long road connecting Gangtok to Chungthang, and that roads and bridges between Meeli and Namchi in south Sikkim and Rawangala in west Sikkim had been severely damaged. All of this hampered rescue operations.

Rumtek, a major Buddhist monastery, located at an elevation of 1,768 metres some 24 kilomters from Gangtok, was badly damaged, leaving some 400 monks without shelter. A team of ten South African engineers were in the Teesta River area working together with the locals to develop a hydroelectric scheme. Two of the men had been inside a tunnel when the quake took place. They were barely able to escape as a major crack developed and the tunnel was suddenly flooded with water from the river. These kinds of stories catch the eye as they find themselves into the newspapers. Inevitably, rumours would emerge that the Teesta hydroelectric project was somehow connected to the earthquake. Needless to say, such rumours are obviously baseless.

The official response to the disaster was quite rapid and effective, it would seem. The Government of India immediately declared Sikkim a disaster area and promised funds for reconstruction and recovery. Prime Minister Singh would visit the quake stricken areas in Sikkim on 29 September 2011. Nearly 6,000 Army and paramilitary forces personnel were deployed without delay. However, their work was hampered by the landslides and it took days for the troops to reach Mangan, the quake's epicentre, and nearby areas of north and west Sikkim, where the heaviest damage had been reported. The rescue convoys were stuck at various locations with fallen trees, downed power lines and landslides. It was reported that two young Army men and a junior engineer had also been killed.

By Monday, Army helicopters started dropping food and supplies to people in the worst affected areas. They also started evacuating people to safety. Apart from the general destruction and lost homes caused by earthquakes, death often comes afterwards from diseases that spread when people must stay in the open and without adequate food, clean water or sanitation.

On Wednesday (21 September 2011) The Times ran an article about how Dipak Ghosh at Jadavpur University had detected abnormalities that could presage a major earthquake. The scientist runs a solid-state nuclear track detector that he has embedded 70 cm underground besides the Faculty Club. As he monitored the devise 9 days before the earthquake, he noticed abnormal fluctuations in radon gas emissions from below. Should he have reported this to warn authorities of the impending danger? This would have been risky, as earthquake prediction is far from an exact science. In 2009 when a 6.3 magnitude quake destroyed the medieval city of l'Aquila in the Abruzzo region of Italy, a local scientist Giampaolo Giuliani had recorded similar forewarnings from his four radometers in the area. He however was under injunction barring him from reporting the monitoring data, as officials claimed that such predictions would spread unwarranted panic. In that quake, 308 people including 20 children died, 1,500 were injured and perhaps 80,000 left homeless.

Ghosh, Director of the Biren Roy Research Laboratory for Radioactivity and Earthquake Studies at Jadavpur University, was well aware of the criticism that Giuliani had had to face around his earthquake predictions. "It is not so easy. I am into this research monitoring soil radon since 2006," he told The Times. "What I gathered from the data is that there is a direct correlation between the soil radon anomaly within 1,000 kilometres from the measuring site, and for intensity above 4 in the Richter scale. They occur 7-15 days before an earthquake with few exceptions," said Ghosh, comparing earthquake prediction based on radon with a doctor performing an ECG on patient, which would indicate that the person is at risk of a heart attack but would not be able to predict its timing. Earthquake forecasting using radon monitoring remains controversial amongst the scientific community.

On Thursday, when many people had slowly started returning home—or whatever was left of it—for shelter from the continued rain, an aftershock of 3.9 shook Gangtok at 22:30 sending people scurrying out into the open. During the same evening, a 4.8 magnitude quake, with its epicentre in Myanmar, was felt in parts of Meghalaya, Manipur, Tripura and Mizoram in northeast India, but there were no reports of casualties according to Mail Today (23 September 2011).

As always, it is the regular people, poor folks eking out a living in the harsh environment where flat agricultural land is hard to come by and where it has been constructed on elaborate terraces for generations, that are most affected by disasters such as this. These are the people who lost family members amongst the dead.

As I left Delhi on Saturday night, it was reported that fresh landslides in Langchun in the rain-soaked northern Sikkim were again stopping rescuers from reaching remote villages. The landslides and the aftershocks would continue for the days and weeks to come. Casualty figures from Sikkim's neighbours confirmed 6 dead in Nepal and 7 in Tibet; 2,322 and 2,960 buildings, respectively, were completely destroyed in these states. On 28 September 2011, authorities downgraded the casualty estimates in Sikkim from 77 to 60 following verification of double counting and locating people who had been listed as missing in the confusion of the immediate aftermath of the earthquake. This at least was good news.

What had taken place was an earthquake with an epicentre in Sikkim, hundreds of kilometres away from the national capital region. The quake hit the Sikkim-Nepal border area at 18:10 hours near the boundary between India and Eurasia plates. It was 6.8 on the Richter Scale and, given the style of construction and rough hilly terrain, it would turn out to be the most destructive earthquake to hit India in ten years. People rushed out of the houses that started to collapse. In addition, there were reports of extensive landslides and downed power lines. "Tremors were felt between 30 seconds to one minute in some parts of Sikkim, including Gangtok," the State capital, said Shalesh Nayak, Secretary in the Indian Earth Sciences Ministry, said according to The Times of India (19 September 2011). Nearly everyone in Sikkim and Darjeeling spent Sunday night in the open as aftershocks triggered fears of a second wave of destruction.

Sikkim is a Himalayan state in the Indian northeast, bordered by Nepal to the west, Tibet (China) to the north and Bhutan to the east. Its southern border is with the Indian state of West Bengal. The mountainous State is quite sparsely populated—according to the latest 2001 census, the total population was only 540,000 people—and only 11% of the people live in urban areas. "Sikkim is sheer magic," gushes the State's official website. "This is not just the most beautiful place in the world but cleanest and safest too," it continues. This pristine idyll was shattered by the quake.

Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh called Sikkim's Chief Minister Pawan Kumar Chamling, who reportedly described the damage as serious. Early reports confirmed 15 dead in Sikkim and across the border in Nepal, but the death toll would keep on rising. By the following Saturday, 24th of September, there were reportedly 75 dead and more than 61,000 left homeless in Sikkim alone. In addition, 10 people were reported dead in Bengal and 7 in Bihar. And the rescue crews had not yet reached the most remote areas due to landslides and heavy rains.

On Tuesday, 20 September, The Times reported that virtually nothing was left intact on the 100 km long road connecting Gangtok to Chungthang, and that roads and bridges between Meeli and Namchi in south Sikkim and Rawangala in west Sikkim had been severely damaged. All of this hampered rescue operations.

Rumtek, a major Buddhist monastery, located at an elevation of 1,768 metres some 24 kilomters from Gangtok, was badly damaged, leaving some 400 monks without shelter. A team of ten South African engineers were in the Teesta River area working together with the locals to develop a hydroelectric scheme. Two of the men had been inside a tunnel when the quake took place. They were barely able to escape as a major crack developed and the tunnel was suddenly flooded with water from the river. These kinds of stories catch the eye as they find themselves into the newspapers. Inevitably, rumours would emerge that the Teesta hydroelectric project was somehow connected to the earthquake. Needless to say, such rumours are obviously baseless.

The official response to the disaster was quite rapid and effective, it would seem. The Government of India immediately declared Sikkim a disaster area and promised funds for reconstruction and recovery. Prime Minister Singh would visit the quake stricken areas in Sikkim on 29 September 2011. Nearly 6,000 Army and paramilitary forces personnel were deployed without delay. However, their work was hampered by the landslides and it took days for the troops to reach Mangan, the quake's epicentre, and nearby areas of north and west Sikkim, where the heaviest damage had been reported. The rescue convoys were stuck at various locations with fallen trees, downed power lines and landslides. It was reported that two young Army men and a junior engineer had also been killed.

By Monday, Army helicopters started dropping food and supplies to people in the worst affected areas. They also started evacuating people to safety. Apart from the general destruction and lost homes caused by earthquakes, death often comes afterwards from diseases that spread when people must stay in the open and without adequate food, clean water or sanitation.

On Wednesday (21 September 2011) The Times ran an article about how Dipak Ghosh at Jadavpur University had detected abnormalities that could presage a major earthquake. The scientist runs a solid-state nuclear track detector that he has embedded 70 cm underground besides the Faculty Club. As he monitored the devise 9 days before the earthquake, he noticed abnormal fluctuations in radon gas emissions from below. Should he have reported this to warn authorities of the impending danger? This would have been risky, as earthquake prediction is far from an exact science. In 2009 when a 6.3 magnitude quake destroyed the medieval city of l'Aquila in the Abruzzo region of Italy, a local scientist Giampaolo Giuliani had recorded similar forewarnings from his four radometers in the area. He however was under injunction barring him from reporting the monitoring data, as officials claimed that such predictions would spread unwarranted panic. In that quake, 308 people including 20 children died, 1,500 were injured and perhaps 80,000 left homeless.

Ghosh, Director of the Biren Roy Research Laboratory for Radioactivity and Earthquake Studies at Jadavpur University, was well aware of the criticism that Giuliani had had to face around his earthquake predictions. "It is not so easy. I am into this research monitoring soil radon since 2006," he told The Times. "What I gathered from the data is that there is a direct correlation between the soil radon anomaly within 1,000 kilometres from the measuring site, and for intensity above 4 in the Richter scale. They occur 7-15 days before an earthquake with few exceptions," said Ghosh, comparing earthquake prediction based on radon with a doctor performing an ECG on patient, which would indicate that the person is at risk of a heart attack but would not be able to predict its timing. Earthquake forecasting using radon monitoring remains controversial amongst the scientific community.

On Thursday, when many people had slowly started returning home—or whatever was left of it—for shelter from the continued rain, an aftershock of 3.9 shook Gangtok at 22:30 sending people scurrying out into the open. During the same evening, a 4.8 magnitude quake, with its epicentre in Myanmar, was felt in parts of Meghalaya, Manipur, Tripura and Mizoram in northeast India, but there were no reports of casualties according to Mail Today (23 September 2011).

As always, it is the regular people, poor folks eking out a living in the harsh environment where flat agricultural land is hard to come by and where it has been constructed on elaborate terraces for generations, that are most affected by disasters such as this. These are the people who lost family members amongst the dead.

As I left Delhi on Saturday night, it was reported that fresh landslides in Langchun in the rain-soaked northern Sikkim were again stopping rescuers from reaching remote villages. The landslides and the aftershocks would continue for the days and weeks to come. Casualty figures from Sikkim's neighbours confirmed 6 dead in Nepal and 7 in Tibet; 2,322 and 2,960 buildings, respectively, were completely destroyed in these states. On 28 September 2011, authorities downgraded the casualty estimates in Sikkim from 77 to 60 following verification of double counting and locating people who had been listed as missing in the confusion of the immediate aftermath of the earthquake. This at least was good news.

Published on October 02, 2011 16:19

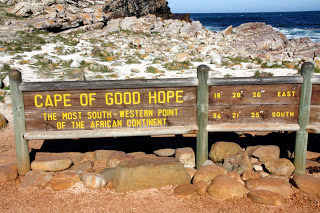

Cape Town R&R

The extraordinary beauty of the city and how it sits on the oceanic front and sprawls into the valleys between the mountains was evident seen from the air as we descended in the rapidly darkening dusk. I had specifically asked for a window seat and not over a wing so as to have the chance to behold what I anticipated would be a gorgeous landing. But this was even more beautiful, as the changing colouring of the landscape conspired to make the scene mystical. First, the sun shone bright, almost dark red seemingly at the level of the plane. Soon it disappeared behind the western horizon sinking into the Atlantic Ocean leaving an orange glow in the sky. There were narrow vertical layers of high clouds that were gilded by the sun's last rays, while the lower level clouds hanging languidly over the valleys were turning dark. Below, the city lights were already on as the night had fallen on the ground. City suburbs and the vineyards of Stellenbosch and Kirstenbosch were connected by the pearly strings of roads on which car headlights were moving. The Table Mountain stood black surrounded by twinkling city lights. In the harbour off the coast a few large container ships were moored with all their lights glittering against the water.