Alix Hawley's Blog, page 13

July 26, 2015

Scenes from Authorial Life

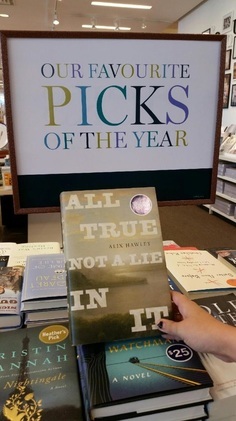

The book photo is at Chapters on Broadway in Vancouver, and is thanks to my sister-in-law. The feet (and dirt) are mine, working on the sequel to All True in my dad's shed and unaware that they were the subjects of her photography. Nothing but glamour.

Published on July 26, 2015 13:01

July 24, 2015

Storybrain: Seven Questions for Kevin Hardcastle

Kevin Hardcastle is in the house this week, with his evocative surname and a discussion of his evocative new story, "Most of the Houses Had Lost Their Lights," which appears along with an in-depth interview in the current New Quarterly (I'll post a link as soon as it's up). We are both Walrus short-fiction alumni (check another great recent Hardcastle story, "Montana Border," there). We are also united in writing about beatings (as you might know from various cases in All True), and in hassling Naben Ruthnum, interviewed in this very blog a few weeks ago!

Kevin Hardcastle is in the house this week, with his evocative surname and a discussion of his evocative new story, "Most of the Houses Had Lost Their Lights," which appears along with an in-depth interview in the current New Quarterly (I'll post a link as soon as it's up). We are both Walrus short-fiction alumni (check another great recent Hardcastle story, "Montana Border," there). We are also united in writing about beatings (as you might know from various cases in All True), and in hassling Naben Ruthnum, interviewed in this very blog a few weeks ago!Kevin studied writing at the University of Toronto and at Cardiff University. He was a finalist for the 24th annual Journey Prize in 2012, and his short stories have been published broadly . He also has new short fiction in The Fiddlehead, and more will appear in Best Canadian Stories. His debut short story collection, Debris , will be published by Biblioasis in September 2015. His novel, In the Cage , will also be published by Biblioasis in fall 2016.

I had a particularly good time asking Kevin about this story because I love the bang of an opening, and the quiet menace and strain around Kayla, the main character. Also because this is one writer who is particularly clear on his process, which is a pleasure to learn about.

1. Did you have any alternate titles for the story? What made you pick "Most of the Houses Had Lost Their Lights"? Did that come to you fully formed at the start, or later?

I am not great with titles, to be honest, and they either come to me early on as I’m writing, or they don’t come to me at all and I’ve gotta rifle through the thing and figure one out. This one wasn’t too painful, however unwieldy it might be, as it was a line straight out of the part of the story with the storm and the floods. I got lucky in that it just seemed like a line that suited the rest of the story and what it was all really about. But generally with titles, either I know it early or I’m flipping through it for something that works.

2. How did you start--an image, a word, a general idea?

I started with that scene in the storm, and that was the first thing I wrote for this story. Usually I plot all my stories from beginning to end, and follow the main signposts pretty closely. This is one where I originally started with that scene, wrote almost an entirely different story for a while, and then threw it away and went back. That doesn’t usually happen and it was a good experience to see if I could keep that initial idea of the storm and the floodwaters ruining their apartment, and their eventual journey to that ending, but change the entire story around it.

Overall, I am a character-focused writer and any greater idea is usually tied to the main characters from the start, and what is happening to them. I think character and atmosphere are the things I lean on most to build a story.

3. How did you find the sense of an ending--did you know when to finish? Did the ending remain the same through different drafts?

As I mentioned, this was well on the way to being a totally different story in the middle-sections before I threw it out. But I did always have Matthew going into the hospital, and Kayla between homes trying to keep it together and find a spot for them both when he was well enough to leave. Because those points were still plotted, I knew it would end with them on the floor or on the grass, or in a tent, some such thing, and it would be ambiguous as to what their chances were after Matthew got out and tried to settle in to whatever place she’d found. Because I had the main events for the characters set, the story sort of kept its focus however it might have changed or had parts replaced in the middle of it.

I usually have a sense of the ending when I begin the writing, and I rarely have significant changes to the endings anymore. Actually, I usually write slow and don’t move on from any one line until it is as good as I can get it, which, if you can tolerate that pace, really streamlines the revisions. In almost every story in my forthcoming collection, Debris, I plotted the thing, wrote one first draft, a second draft for larger problems like lines or passages to cut down, and then a third and final draft for nuts and bolts issues. That’s usually all the drafts there are. Though, I do like to continuously look back and what I wrote earlier, and clean it up some before continuing with the story. Many writers seem to do these very rough drafts and shape it up from there. That doesn’t work for me as well, though this story did get taken apart and put back together more than any other I’ve published.

4. Could you choose a piece of music to go with this story?

How about Cover Me Up by Jason Isbell. Many of them would go well with Drive-By Truckers songs, and Isbell wrote some of my favourite Truckers songs before he moved on to his own records. It’s sort of a flip in that the song is from the perspective of a man trying to get sober and recover for his better half, but I think it suits this story, as a song about two young people trying to get through the wars together.

5. Your other stories I've read are about male characters. How did you find it to write about a female protagonist? (I struggled some with writing as Dan in All True, and your character read as real to me, for instance in the scene with the sweat sticking her dress to her back and frizzing out her hair.)

This is something that I was real curious about, in how this story would be received by readers. But I was bolstered a bit by the reaction to another story of mine that was published in Shenandoah last year (the title story in Debris). That one started as a two-hander with an old couple at the heart of it, but it quickly became the wife’s story and she became the standout character, and the one who drives the entire narrative. That story was well received, and that gave me some confidence with this one.

You are likely not going to see me start writing first person stories with a female protagonist, and you will not see me suppose things that I don’t know at all on an experiential level. As long as I stay in my wheelhouse with any character, I think I’ll not write about it too terribly. In another interview, I was asked about my female characters being violent and doing things that are supposedly manly. Well, in my experience, I’ve known a lot of women who ran the household and carried the family and I’ve known others who could do that and then smack the teeth out of your head. If anything, I’d feel more limited in ability if I were to write about a certain class of character, or a character with very different priorities than most of mine have, rather than those just differentiated by gender. Otherwise, I figure you always have to be paying attention to physical behavior if you are a writer of any worth to begin with, and have some empathy, which gets you pretty far. It also helps that I write very little about the explicit thoughts of characters, and focus more on the physicality of what they are doing.

6. Your diction tends to smack us every so often with unexpected words, sometimes archaic ones. Where does that come from?

At this point I’m not even sure that I can figure out the exact origin off all of my odd or antiquated word choices. Not exactly anyway. But I have read a lot of writers from rural areas, and from the south and southwest in the US, and I come from a rural place in Ontario with all kinds of interesting folks. I think, especially with dialogue, I’ve mashed a lot of those elements together to create the rhythm and tone of certain lines, and it has certainly informed some of the words I use regularly.

Some of it is folksy, some of it American perhaps, and some of it is just because I like the word better than whatever is commonly used, whether the sound of the word or how it reads in a line. I've certainly followed a lesser Cormac McCarthy philosophy of using archaic words for the effect as long as their meaning is correct. It also puts a story out of time to some degree, making it harder to pigeonhole. Strangely, that kind of unusual writing can lend a permanence and a sense of universality that is often lost with more conventional language. That is probably easier said for a world-class writer like McCarthy, and not for me, but it is on my mind. I also started working unconventional phrases and modes of speech into the actual narrative voice as well, along with profanity, and it all tends to work somehow, whether it is proper English or not.

7. For a while I've been interested in a kind of Canadian Gothic in fiction (this comes up in my own writing too). This story isn't all that Canadian on the surface, but it has that Gothic quality I've noticed--quiet fear, sudden violence, animals, etc. Can you comment on that?

As in the previous question about language, I do also think that I’ve been influenced in setting and atmosphere by a lot of the southern-based US writers I read, and their approach to handling that kind of material. There is certainly a lot of Canadian writing that deals with the natural world and the wildness and danger and violence therein, but I feel like there are many circumstances where a writer follows certain tropes and patterns that ultimately deaden the impact and potency of these gothic elements. Often we see the natural world or violence or the terrain qualified by the characters constant thoughts on it and whether they want to be there or are trying to escape to it or from it.

Since I tend to read many American writers firmly rooted in this tradition, such as McCarthy and Daniel Woodrell and Willa Cather, I think it happened that I wrote this kind of material in such a way that the characters don’t have a specific agenda or a catharsis or magical epiphany or anything like that, some profound realization supported by a change in environment or by violence or by being under siege in some way by their surroundings. They just live in it and deal with it accordingly. The gothic elements aren’t a device or tool, but more another character or essential element of the story. There is a wealth of this kind of material for a Canadian writer if they are willing to write about it without trying to justify or qualify it to the audience. And they shouldn’t run away from it. They should run toward it without feeling compelled to explain why or rationalize it for the reader.

Published on July 24, 2015 16:39

July 17, 2015

Storybrain: Seven Questions for Connie Gault

I'm enjoying this interview series a little too much. My original scheme was to give everyone the same five questions, but I had two extra for Connie Gault this week, so we'll see if I can keep myself under control from here. Ahem.

I'm enjoying this interview series a little too much. My original scheme was to give everyone the same five questions, but I had two extra for Connie Gault this week, so we'll see if I can keep myself under control from here. Ahem. I just finished Connie's newest novel, A Beauty (McClelland and Stewart, 2015). Full disclosure: I figured the Depression on the prairies wasn't going to be my thing (I've tried a lot of prairie novels, I swear, but I was born in BC, and it shows). But Connie manages to make the period shimmer and swerve all over the place in this story of attraction and loss. She's a slyly funny writer, gifted beyond merely beautiful turns of phrase. (I caught a little of that smartness in Toronto when our books came out this February.) I'm glad to know a fellow Dickens and Woolf fan, and to see their threads in her writing.

Connie has quite an authorial bio: she's the author of two short story collections, numerous plays for stage and radio, and the co-author of a feature film, Solitude. Her novel, Euphoria, won the 2009 Saskatchewan Book Award for Fiction and was short-listed for the High Plains Fiction Award and the Commonwealth Prize for Best Novel of Canada and the Caribbean. A former prose editor of grain magazine, Connie has also edited books of fiction and has taught many creative writing classes and mentored emerging writers.

1. Did you have any alternate titles for the book? What made you pick A BEAUTY? Did that come to you fully formed at the start, or later?

I find titles hard. I sent the novel out as Elena Huhtala, knowing it wouldn’t fly because no one would know how to pronounce the name. Ellen Seligman, my editor, suggested Elena H. We both liked it for its sense of mystery, but after several months I started feeling unhappy about the use of the intital. I thought up dozens of titles that didn’t work, and then suggested A Beauty. I like it for its old-fashioned ring; we don’t call a woman a beauty anymore, and for good reason, since it calls attention to her external qualities. There is also another kind of beauty in the lost lives and lost hopes in the novel. So the title seems to do what I want a title of mine to do — say something, but not too much.

2. How did you start this novel--an image, a word, a general idea?

This novel started with the image of a young woman opening a car door and stepping down to the road. I knew she was going to take off down that road on her own. I knew she was going to cause trouble, like most strangers who come to town. I didn’t know who she was except that she was lovely and sexy and exotic. And poor.

3. How did you find the sense of an ending--did you know when to finish? Did the ending remain the same through different drafts?

I love Frank Kermode’s book, The Sense of An Ending. And I believe that fictions are for finding things out, as he says — but that doesn’t necessarily mean wrapping up the plot. In a book that raises questions about the influence of the past and the future on the present, I wanted to leave the characters at a point where the future was open to them. I hoped that by leaving the road open, I would let readers discover things that were important to them, ideas about the choices we make, how we live our lives, how we influence others.

The ending of this novel didn’t change much with rewriting. I experimented with some changes in the last chapter, but I rejected those and went back to the original, so the tenor of the ending and the events stayed pretty much the same. I worked mostly on the dialogue. What people say to each other at the end of a novel is crucial, and I wanted to handle it as delicately as possible.

4. Could you choose a symbol to represent this story? A shape, person, piece of music, anything you like?

If there were something, it would be open, calm, quiet. Maybe the smell of dust and weeds carried on a warm, barely perceptible breeze.

5. Did anything in the story grow out of autobiographical experience? Did writing it change your view of the past?

My grandfather deserted his large family in the middle of the Depression. He walked away and never returned. The story intrigued me when I was a girl, and the novel grew out of that. My feelings about that event didn’t change, but I did learn something by writing about the past, and especially through using two time frames, since the last third of the novel, set in the 60’s, becomes the characters’ present. I didn’t realize how much the passage of time is about loss, or how sad the loss can make you. That sounds self-evident when I think about it, but as I was writing, in the two times that were both long past to me, I was haunted by the fact that people have to die, that our futures are limited by that end, and that nothing we make lasts, there is no forever.

6. Your book shifts in voice and point of view, from third person to first and back. How did this come about?

The section Ruthie narrates was the first part I wrote. After I went back to write the start of Elena’s road trip, I tried — for a few minutes —to translate Ruthie’s part into third person. Didn’t work. Couldn’t work. Ruthie was irrepressible; she had to speak her mind. I rationalize this aesthetically because of the bond the two girls form. Elena changes Ruthie’s life, and in a more subconscious way, the reverse also happens.

7. A BEAUTY gets us inside quite a few characters in an almost Dickensian way. Do you think any classic novels influenced your work's structure or style?

I can’t draw the lines, but I’d be happy to believe I learned something from my two favourite dead authors, Dickens and Virginia Woolf. I love them both for the way they idiosyncratically portray their characters’ inner lives, and the way they rise above ordinary prose, and the way they tap into images as potent as the ones your remember from childhood.

Published on July 17, 2015 14:23

July 16, 2015

12 to Watch

I'm surprised and thrilled to be included as a "rising CanLit star" on CBC Books' list of 12 Writers to Watch for 2015. And I'm feeling rather smug about having interviewed fellow watchees Chelsea Rooney and Emma Hooper here on this blog.

I'm surprised and thrilled to be included as a "rising CanLit star" on CBC Books' list of 12 Writers to Watch for 2015. And I'm feeling rather smug about having interviewed fellow watchees Chelsea Rooney and Emma Hooper here on this blog. You can watch this very space for more Storybrain, coming tomorrow.

Published on July 16, 2015 15:57

July 12, 2015

Storybrain: Five Questions for Naben Ruthnum

In spite of his lack of appreciation for question 4 (I was SO SURE he'd have a death metal song or 1990s power ballad for me), I'm happy to have Naben Ruthnum's answers about his writing process. I knew him in Kelowna when he was five and unsmiling, and later, he was in the prog-rock band Bend Sinister with my brother. He's now a terrific unsmiling writer with a crime fiction column at the National Post and the 2013 Journey Prize for short fiction. He has a book or two underway, and a sharp short story, "Working Clean," in the current issue of The Walrus. Call it post-noir, maybe?

In spite of his lack of appreciation for question 4 (I was SO SURE he'd have a death metal song or 1990s power ballad for me), I'm happy to have Naben Ruthnum's answers about his writing process. I knew him in Kelowna when he was five and unsmiling, and later, he was in the prog-rock band Bend Sinister with my brother. He's now a terrific unsmiling writer with a crime fiction column at the National Post and the 2013 Journey Prize for short fiction. He has a book or two underway, and a sharp short story, "Working Clean," in the current issue of The Walrus. Call it post-noir, maybe? 1. Did you have any alternate titles for the story? What made you pick "Working Clean"? Did that come to you fully formed at the start, or later?

The initial title was "Cowards," which I never quite liked. It seemed too much like an instruction on how to correctly read the story. Plus, I don't really think that these characters are cowards, not really. Nick Mount (the fiction editor at the Walrus) also didn't like it. The next title I came up with was "Stage Time," but as my friend Andrew Sullivan said, that title is so plain that I might as well have used "Comedy Story." So I sent up a flag for help, and my friend Kris Bertin and I looked through twelve-step terminology and comedy lexicons until Kris found "Working Clean," which has a great ambiguity about it. Thanks, Kris.

2. How did you start this story--an image, a word, a general idea?

It started with the idea of a standup using a twelve-step meeting as another place to get stage time, to work against his nerves and also build material. The ambition angle came in later, as well as the idea of that deception of the protagonist's forming the foundation of his career and life.

3. How did you find the sense of an ending--did you know when to finish? Did the ending remain the same through different drafts? (*I think it's amazing, by the way.)

I wrote this whole story on a flight from Kelowna to Toronto, after many weeks of trying to see how it would fit together. But the major plot points haven't changed from that first draft. I didn't realize, myself, that Jeev was being deceptive until I wrote it that way. It seemed like a natural fit, and also suggested something important about the relationship that performers and artists have with each other--how they guard their own, and each other's, lies.

4. Could you choose a symbol to represent this story? A shape, person, piece of music, anything you like?

Yuck, Alix.

5. Did anything in the story grow out of autobiographical experience? Did writing it change your view of the past?

Well, all the comedy and AA stuff comes from research. I haven't tried either. But the ambition and commitment stuff, that has a lot to do with my own attitudes, even if there's a ruthlessness in these characters that I'm glad to lack. Writing it did legitimize some of the hundreds of hours that I've spent listening to comedians and shock jocks, so it did affect my view of the past in that sense, yeah.

I think about the more exposed, performance-based arts a lot, probably because of the years I spent playing music. There's something about presenting your work in the immediate present to a likely-hostile crowd that I think is invigorating and continues to influence the way I write and attempt to present my work.

Published on July 12, 2015 15:37

July 3, 2015

Storybrain: Five Questions for Guillaume Morissette

I met Guillaume Morissette in Toronto in May, and read his novel, New Tab, soon after that. Guillaume is quick, smart, and deadpan, very easy to talk with. He also looks good in photos. New Tab (Vehicule Press) was shortlisted for the 2015 Amazon.ca First Novel Award, and manages the tricky balance of despair and wit. He creates an engaging picture of how many live now, working at pointless office jobs and wriggling in and out of apartments and relationships. Guillaume's work has appeared in Maisonneuve Magazine, Little Brother Magazine, Electric Literature, and many other publications. He is the co-editor of Metatron, a small press based in Montreal, where he lives. www.guillaumemorissette.com

I met Guillaume Morissette in Toronto in May, and read his novel, New Tab, soon after that. Guillaume is quick, smart, and deadpan, very easy to talk with. He also looks good in photos. New Tab (Vehicule Press) was shortlisted for the 2015 Amazon.ca First Novel Award, and manages the tricky balance of despair and wit. He creates an engaging picture of how many live now, working at pointless office jobs and wriggling in and out of apartments and relationships. Guillaume's work has appeared in Maisonneuve Magazine, Little Brother Magazine, Electric Literature, and many other publications. He is the co-editor of Metatron, a small press based in Montreal, where he lives. www.guillaumemorissette.com1. Did you have any alternate titles for your book? What made you pick New Tab? Did that come to you fully formed at the start, or later?

In 2012, I published a collection of stories and poems called “I Am My Own Betrayal” through a small art press in Montreal. I still like that title, but it’s also melodramatic a little, so I was looking for a title that was maybe broader and more neutral for my novel.

My working title for a while was “All my relationships are ambiguous relationships,” but it still seemed too self-involved. “New Tab” started almost as a joke, like it just made me laugh to imagine a novel titled that. Over time, I grew to like how it would signal to the reader that this is a “contemporary” novel, and how it went well with the theme of self-reinvention that runs throughout the book. By that point, titling my novel New Tab seemed both perfectly stupid and perfectly logical to me.

2. How did you start this book--an image, a word, a general idea?

When I was studying Creative Writing, a short story that I submitted to a fiction workshop got kind of trashed. My stories usually did well, so the negative feedback for this one caught me off-guard a little. Several months later, I re-opened the file containing that story and re-read it in full and was like, “Holy shit, this is really bad, I have no idea why I thought this was good.” Still, there was something in that piece that I liked, like it was trying to do too much but at the same time, it was also full of ideas and creative energy and stuff. I started re-writing the story from scratch and a part that was 500 words became 5000 words and then it didn’t seem to me like I was writing a short story anymore. In the final version of New Tab, you can still find a few descriptions that were in the original story, like they’re haunting the text or something.

3. How did you find the sense of an ending--did you know when to finish? Did the ending remain the same through different drafts?

Novels and poems are similar in the sense that you usually know where something starts, what the first line is going to be, but you rarely know where it’s going to end. You just hope that you’ll be able to figure out an ending that sort of makes sense and ties everything together nicely.

I had no idea what the ending of New Tab was going to be until I had a draft that was maybe 80% done. I was walking home from the grocery store or something and the last four-five sentences that end the book just came to me in a rare moment of clarity. I ended up working backwards from there, knowing that I wanted those four-five sentences to close the book.

4. Could you choose a symbol to represent your book? A shape, person, piece of music, anything you like?

New Tab, to me, is about self-sabotage/self-reinvention, so maybe some sort of depressed phoenix, I don’t know.

5. Did the book grow out of autobiographical experience? Did writing it change your view of the past?

New Tab is semi-autobiographical. I had material from real life that I felt strongly about, but I wasn’t interested in writing a memoir or something, so I decided to allow myself to play with the material a lot and just write something that I would enjoy reading, without caring about what’s “real,” what’s embellished and what’s made up. In the end, I like how the book has one foot in reality, how it’s both close to me and totally removed from me, like you can read it without knowing or caring that it’s based on my own experiences.

Published on July 03, 2015 09:08

June 26, 2015

Storybrain: Five Questions for Ashley Little

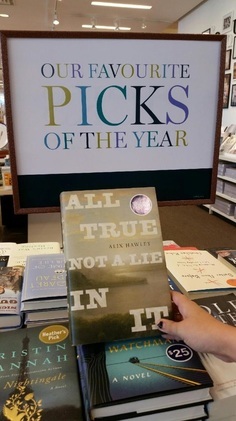

Ashley Little is a mind-blowingly gifted writer, and reading her novel Anatomy of a Girl Gang is like being hit by a truck. Told in six powerful voices, it's her third novel, and won the Ethel Wilson BC Book Prize, and was longlisted for the Dublin IMPAC Award. Ashley was born in Calgary, and completed her BFA in Creative Writing and Film Studies at the University of Victoria and her MFA in Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia. In spite of the violence and energy of her work, she comes across as gentle and soft-spoken, a paradox I love. I'm so interested in how she created the shape of her book.

Ashley Little is a mind-blowingly gifted writer, and reading her novel Anatomy of a Girl Gang is like being hit by a truck. Told in six powerful voices, it's her third novel, and won the Ethel Wilson BC Book Prize, and was longlisted for the Dublin IMPAC Award. Ashley was born in Calgary, and completed her BFA in Creative Writing and Film Studies at the University of Victoria and her MFA in Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia. In spite of the violence and energy of her work, she comes across as gentle and soft-spoken, a paradox I love. I'm so interested in how she created the shape of her book.1. Did you have any alternate titles for your book?

Yes, She Walks Softly, ripped off from the Ice-T song, Big Gun. I now hate that title, although I still like the song.

Also, The Black Roses, which is the name of the gang.

2. What made you pick the one you did? Did that come to you fully formed at the start, or later?

It was one of the first titles I had in mind before I started writing and I liked it the best. I think Anatomy works on a few levels because it is both the study of something and helped me to think about the gang as a living organism; a single biological unit.

3. How did you start this book--an image, a word, a general idea?

After almost three years of research, I heard the character Sly Girl’s voice in my head. She said, “I was shot in the face three years ago.” I knew that was the first line of the novel and that I was ready to start writing it.

4. How did you find the sense of an ending--did you know when to finish? Did the ending remain the same through different drafts?

My original ending was deemed “too hopeless” by my agent and other editors. I was coerced into writing a more hopeful ending which I resented at the time because I thought it felt tacked on and sugary, but now I’m happy that I did. Now I see that it works better that way (even though I couldn’t at the time) and I’m glad they gave me that push. I personally really like down-endings, but I think most readers don’t or can’t handle them. Or they don’t sell. Something like that. One day I’ll write a book with a down-ending and it will sell really well and I’ll prove them all wrong.

4. Could you choose a symbol to represent your book? A shape, person, piece of music, anything you like?

Yes, it is this cover of Straight Outta Compton (N.W.A.) by Nina Gordon of Veruca Salt. I probably listened to this song over a thousand times while thinking about and writing Anatomy of a Girl Gang.

5. Did the book grow out of anything autobiographical? Did writing it change your view of the past?

The novel’s setting came from an inexplicable attraction that I had to Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Sometimes I felt like I was using the research for the novel as an excuse just to go down there and hang around. But after spending years researching that space and thinking about, visiting it, reading about it, writing about it, watching films on it, and talking about it, I don’t feel the need to go there anymore when I’m in Vancouver. It’s like I got it out of my system. I figured out what I needed to know about it and what it meant to me, and that was important for me on a personal level, outside of anything to do with the novel.

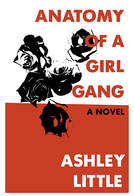

A painting that inspired Ashley throughout her writing of Anatomy of a Girl Gang. LAgraffitigirls.com.

A painting that inspired Ashley throughout her writing of Anatomy of a Girl Gang. LAgraffitigirls.com.

Published on June 26, 2015 10:52

June 20, 2015

Storybrain: Five Questions For Emma Hooper

Published on June 20, 2015 17:35

June 12, 2015

Storybrain: Five Questions for Chelsea Rooney

Being rich in smart writer friends, and interested in how the brain creates stories, I had the idea of starting a series asking some of them about how their work was shaped. Chelsea Rooney is the inaugural Storybrain! The author of Pedal, a brilliant and powerful debut novel (Caitlin Press), which was a finalist for the 2015 Amazon.ca Award and a 49th Shelf Book of the Year, Chelsea hosts a monthly episode of The Storytelling Show on Vancouver Co-Op Radio.

Being rich in smart writer friends, and interested in how the brain creates stories, I had the idea of starting a series asking some of them about how their work was shaped. Chelsea Rooney is the inaugural Storybrain! The author of Pedal, a brilliant and powerful debut novel (Caitlin Press), which was a finalist for the 2015 Amazon.ca Award and a 49th Shelf Book of the Year, Chelsea hosts a monthly episode of The Storytelling Show on Vancouver Co-Op Radio.I love talking with Chelsea as much as I love reading her stuff. She is just as smart in life as she is on the page. Read more at chelsearooney.com.

1. Did you have any alternate titles for your book? What made you pick Pedal, and where did it come from?

Alternate titles are funny to recall, because they so clearly mirror certain stages of my research. The first, sly, Wicked Little Girls followed by the angrier Fuck Trauma. I settled on Pedal for its movement and verve. The word has momentum. The novel is short and moves quickly. The narrative spans just several weeks, with plenty of flashbacks filling the cracks. I also liked how “pedal” echoed a main theme, pedophilia.

2. How did you start this book--an image, a word, a general idea?

In 2009 I tried riding my bicycle from Vancouver to Nova Scotia. I was twenty-five years old and a mess: fresh out of a five-year relationship, my mother newly diagnosed with early-onset dementia. I was biking home to be with her. The trip was difficult, but one moment of joy stands out. A sunny morning in Banff, Alberta. Riding along the Bow River, teal with glacial silt. And beside the river in a field, a herd of deer, running with us as we rode. My cycling partner, a happy Swiss man, whooped with joy and shouted at them, “Come on, girls!” and for a while it seemed as though they were listening to him. It felt magic, like the reason I'd made the trip in the first place. An iteration of that scene appears in Pedal, and it was the first scene I wrote.

3. How did you find the sense of an ending--did you know when to finish? Did the ending remain the same through different drafts?

I'd always had the last scene clear in my mind, but I had no idea how I would get there. It came quicker than I thought, and I was taken by surprise one morning in the coffee shop (April 27th 2012). What a strange and wonderful feeling, closing up the laptop, walking out into the world, having just finished the first draft of my first novel.

4. Could you choose a symbol to represent your book? A shape, person, piece of music, anything you like?

It would have to be the bicycle. It’s the perfect machine. Aside from the earthly materials extracted to construct it, it has no harmful effects on the environment and only positive ones on its rider. You can leave it for days, months, years, and return to it easily. There’s a reason they say, “It’s just like riding a bike.” You can abandon a bicycle, but a bicycle will never abandon you. This kind of faith was the same sort it took to write Pedal.

5. You've been clear about your novel's autobiographical basis. Did writing it change your view of the past? Did the fictional transformations you made affect your view?

Ironically. I started writing Pedal to prove that the experiences I’d had as a child—experiences I’d hesitated to call “abuse”—had no negative impact on me…Insert endless laughs forever here. It wasn’t until I handed Pedal off to readers (thesis advisors, agents, publishers, editors) and heard their readings of it that I began to see my experiences—and their impact—objectively. My certainty was replaced with bewilderment, a state that shaped my rewrites, and a state I now infinitely prefer.

Published on June 12, 2015 15:05

May 23, 2015

Official Photos from Amazon / Walrus Novel Award Night

Published on May 23, 2015 12:21

I'm lucky enough to have persuaded the one and only

I'm lucky enough to have persuaded the one and only  This trophy is beautiful. And heavy.

This trophy is beautiful. And heavy.