Alix Hawley's Blog, page 12

September 18, 2015

Storybrain: Seven Questions for Lee Henderson

I've heard more than one person say Lee Henderson is about the world's coolest man. His books The Broken Record Technique and The Man Game are critically beloved prizewinners. He's also an artist and curator. I saw him read in Victoria in March, which confirmed the reputation that preceded him. Without even trying, he had the room in his very cool fist as he read from his new novel, The Road Narrows As You Go. I was pretty excited when he signed my copy and drew a cartoon dog on the title page. And even more excited when he cheerfully agreed to answer my questions here. His answers echo the way he talks, and like his book are smart, lively, generous.

I've heard more than one person say Lee Henderson is about the world's coolest man. His books The Broken Record Technique and The Man Game are critically beloved prizewinners. He's also an artist and curator. I saw him read in Victoria in March, which confirmed the reputation that preceded him. Without even trying, he had the room in his very cool fist as he read from his new novel, The Road Narrows As You Go. I was pretty excited when he signed my copy and drew a cartoon dog on the title page. And even more excited when he cheerfully agreed to answer my questions here. His answers echo the way he talks, and like his book are smart, lively, generous.The new book is fat, almost Victorian-triple-decker fat. It hums and spits with energy and ideas--the gist involves Wendy Ashbubble, a young and secretly Canadian cartoonist, achieving highs of all kinds in 1980s San Francisco while trying to determine whether Ronald Reagan is her father. It's funny and sexy while being learned and sad (Jackie Collins meets Foucault, maybe?). It made me think about time.

1. Did you have any alternate titles for the book? What made you pick The Road Narrows As You Go? Did that come to you fully formed at the start, or later?

Yeah, what happened was I wrote the book for six years under the title Orphans and then I think it was after I sent that draft to Nicole Winstanley, my editor, in fall of 2013, that I came up with a new title. I remember she once asked me in a phone call after I delivered the draft if I wanted to stick with Orphans and I said I had a new title, and I told her, and she was like, Yeah, let's go with that one. I also told her I wanted to rewrite the entire book from scratch -- so in four and a half months I wrote an entirely new draft, and that's the book. So there's a draft called Orphans that took six years and is radically, ridiculously different than The Road Narrows As You Go.

2. How did you start this novel--an image, a word, a general idea?

Seems I usually get an idea about a location and work out from there. But this novel started in 2004 with the line "Say good-bye to the cartoonist," which rang in my head and still does.

3. How did you find the sense of an ending--did you know when to finish? Did the ending remain the same through different drafts?

Well, this novel was always going to be some kind of weird palimpsest of different competing texts. I make allusions to them throughout the story, about four or five different stories. The main two are Barrie's novel Peter Pan and Antonioni's movie L'Avventura, and I folded these narratives into the 1980s world of junk bonds, AIDS, Satanic Ritual Abuse Repressed Memory Syndrome, and newspaper comics. So the ending of this novel was already written for me, I just had to figure out how to combine the ending of Peter Pan with the ending of L'Avventura using my characters. Most of the book is just a big giant echo of those two stories.

With The Man Game, it was totally different. I had an ending in mind for eight years. I wrote it, submitted it to my editor, Barbara Berson, and she said the book was ready to publish, but needed a different ending. I almost lost my shit. How do you fix just the ending? It seemed impossible. But I also knew she was right. My ending was flat, it was inconclusive and basically it was a digression that avoided the real-deal ending I should have had. So I went on a long long walk. And just when I was about to give up I realized that it's all just fiction, if I can make up beginnings and middles, I can just as easily make up a new ending -- and then in a flash, a whole new ending came to me.

4. Could you choose a piece of music to go with the book?

"Biological Speculation" by Funkadelic off their album America Eats Its Young. Early on I started to imagine the record collection my characters owned, and the whole Parliament-Funkadelic discography became very important to them and my vision of their lifestyle.

5. You've lovingly constructed the entire living world of this book--a joyous, tragic, energetic organism. Some of it is real (actual cartoonists make appearances), some invented. How was it to go through that divide?

In particular it was very difficult to write about Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly -- two people I admire so much, and are so important to the history of contemporary comics because of what they did for the medium in the 1980s through Raw and Maus, etc. They had to be in the book, but those are the parts that took the longest to compose. I have more drafts of the dinner scene with them than anything else. I probably wrote it a good dozen times. It's one of the few scenes that stuck around from Orphans.

6. What was it about the 1980s Ronald Reagan that made you place him at the centre of the protagonist Wendy's dreams, shadowy as he is?

Yeah, Wendy is pretty sure Reagan's her absentee father -- he's this big absurd clown-cartoon of a patriarch presiding over the unfettered greed and free-market decadence of the 1980s, and she loves him unconditionally. Her obsession with Reagan is part of how she sheds her Canadian identity. By making Reagan her father, in her mind, she's already half-American. He was witty and brave, he won the Cold War, he ate jelly beans and connected with regular folks, but he set back AIDS research by a decade, he encouraged a privatized prison system, he was responsible for the Iran-Contra deal, and he kickstarted the hypocrisy of the never-ending Drug War. Wendy is equally flawed, and she finds kinship inasmuch Reagan's strengths as his flaws. She's loved him ever since she was a child and watched him host General Electric Theater.

7. AIDS is the black backdrop to all the hilarity. I'm interested in how you decided to write about it this way.

The 1980s were definitely amplified times. It was a loud, pinstriped, and shoulder-padded decade. It was a corporate decade that favoured the populist over the special interest. AIDS cut across the grain of '80s egotism. AIDS is the real subtext, the one subject that perhaps can't be avoided in any kind of proper portrait of the 1980s. And Reagan took the leadership role in the denial of AIDS. He refused to take AIDS seriously and his years of inaction cost America and the world millions of lives, for his voice could have made a big difference on the international stage had he found for AIDS the same kind of passion he found to end the Cold War.

How I decided to create this sense of a black backdrop was to begin on the theme of AIDS in the first chapters and then let that horror hang over the rest of the story, so when the characters get really rapacious and decadent and ego-driven and self-absorbed in later chapters, their 80s attitude seems all the more absurd and tragic. AIDS also becomes the locus in the story for all the questions about what's real and what's not real, what's a fiction and what's a fact, what's a valid fear and what's just an ego on fire.

Published on September 18, 2015 11:48

September 11, 2015

Storybrain: Seven Questions for Melanie Murray

I met my friend Melanie Murray during my first full year of teaching, the year I'd just moved back to Canada, had four new courses to prepare, and hardly slept. I was always relieved to see her in the hallway outside my office--a kind, wise, and calm presence. An experienced professor of literature and composition, she was always generous with her help and course materials, but she claimed she would never publish any creative writing herself. It would have to be posthumous.

I met my friend Melanie Murray during my first full year of teaching, the year I'd just moved back to Canada, had four new courses to prepare, and hardly slept. I was always relieved to see her in the hallway outside my office--a kind, wise, and calm presence. An experienced professor of literature and composition, she was always generous with her help and course materials, but she claimed she would never publish any creative writing herself. It would have to be posthumous.Well. She's very much alive_, and in 2012 published a deeply generous account of her nephew Jeff's life and his death fighting in the Afghanistan war. As you'll see from her answers below, the book weaves myth with family history, biography with personal reaction. It elicited a huge number of responses, and it's hard to believe it's a first book. It's a compelling and beautiful read, and I'm proud to have it as the inaugural non-fiction work on Storybrain.

1. Did you have any alternate titles for the book? What made you pick For Your Tomorrow? Did that come to you fully formed at the start, or later?

The title came early in the writing of the first draft. It’s the epitaph on Jeff’s headstone, and comes from an epitaph on a WW II war memorial in India: For Your Tomorrow / We gave our today. It encapsulates the answer to some of the main questions I was exploring in the book: What compelled my thirty-year-old nephew to abandon his PhD dissertation and enlist in the military? Why was he willing to risk everything in a war on the other side of the world? What does serving one’s country really mean?

2. This is non-fiction, in part a history of your family as well as your nephew's death. You had much to draw on and to cover. So where did you start--an image, a word?

The seeds of the book were sown the day after my nephew was killed. It was during the long flight from Kelowna to my sister’s home in Halifax. Pondering Jeff’s life and death, I began to glimpse a mythical pattern. That night, I pulled Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces from Jeff’s bookshelf and skimmed its pages. I could see in the many passages he’d highlighted, his own story. So the tribute I wrote for Jeff’s memorial service, “A Hero’s Journey,” became the foundation for my book.

3. How did you find the sense of an ending? Did the ending remain the same through different drafts?

I knew from the beginning that the last chapter would be about “Renewal,” the final phase of the hero’s journey, and that it would focus on Jeff’s legacy, particularly his son Ry, born three months before Jeff deployed for Afghanistan. But the actual contents of

the chapter kept shifting as I tried to reach an ending that was life affirming. One July day, about a year after Jeff’s death, I was wading out into the Northumberland Strait with Ry in my arms; on the same shore that Ry’s father, and grandmother, and great

grandfather and great great grandfather had walked. So that Zen moment became the final scene of the book.

4. Could you choose a piece of music to go with the book?

Ry Cooder’s soundtrack for Paris Texas immediately comes to mind. Jeff’s love of Ry Cooder’s music is obviously reflected in his son’s name. And the stark, elegiac tone of his acoustic guitar twanging embodies for me the spirit of the book—thoughtful and sad yet somehow uplifting at the same time.

5. I know this book was very personal and difficult to write. Did finishing it change your view of the past?

Writing the book brought me much deeper into my ancestral past, and made me more aware of the impact of the past on our present lives—that we carry the legacy of our familial, our cultural, and even the mythical past within us; and that they shape us in

ways we’re not really conscious of. The book’s subtitle, The Way of an Unlikely Soldier, reflects this theme. In trying to understand what motivated Jeff’s radical shift in becoming a soldier, I discovered that the sign posts were pointing there all along—from the moment of his birth on Remembrance Day. As my sister lay in labour, she could hear out the hospital window the skirl of bagpipes drifting up the hill from the cenotaph. The bagpipes heralding Jeff’s birth were from the Second Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment—the same regiment that Jeff would support to his death in Afghanistan 36 years later.

6. The voice shifts between your own and a third-person, sometimes imagined view of your nephew's life. Did this structure come naturally? Were some parts easier to write than others?

The shifting points of view existed from the beginning but in a different form—more personal essay juxtaposed with biographical exploration. In the second draft I incorporated more of the devices of fiction to tell the story, creating scenes to show events and develop characters. I imagine scenes in Jeff’s life within the framework of available facts. The most difficult parts to write were the chapters set in Afghanistan. I relied on my reading about the war and the country, as well as many interviews with Jeff’s comrades. But it was a totally foreign setting and experience for me, and I was writing about real people who lived these events, and are still affected by what transpired there. So I was concerned with authenticity and capturing the spirit of the truth.

7. Images from the Afghanistan war blend with classical myth. You mix almost journalistic recounting with ancient stories. I'm interested in your thoughts about how this works in your book.

I was trying to evoke a sense of mythical time, or time immemorial, as opposed to just linear time; and to show that myths are not just dead stories from ancient times, but they resonate in our present lives. As Joseph Campbell puts it, “The myths help you read the messages of the world.” They certainly helped me read my nephew’s life and death in a new and more meaningful way, and I hope they have that same impact in For Your Tomorrow.

Published on September 11, 2015 16:48

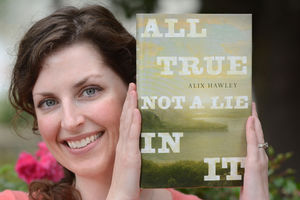

Home, Dan

My agent and I are delighted to announce that All True Not a Lie In It will be published in the US by Ecco. Found out this morning!

Published on September 11, 2015 12:15

September 10, 2015

It's Giller Time

I was sleepy after taking my kids to their second day of the school year, and about to get to work writing at Starbucks when my agent phoned me yesterday morning to say All True had been longlisted for Canada's Giller Prize. That woke me up and made me long for cocktail hour. I'm thrilled to be in such company:

I was sleepy after taking my kids to their second day of the school year, and about to get to work writing at Starbucks when my agent phoned me yesterday morning to say All True had been longlisted for Canada's Giller Prize. That woke me up and made me long for cocktail hour. I'm thrilled to be in such company:I'malso proud to have been interviewing so many great Canadian writers here on Storybrain. Next installment tomorrow!

Photo by Gary Nylander, The Daily Courier

Photo by Gary Nylander, The Daily Courier

Published on September 10, 2015 17:25

September 5, 2015

Storybrain: Seven Questions for Doretta Lau

At last I've coerced the superhuman Doretta Lau into discussing her new story in

Room

magazine, "Best Practices for Time Travel." When not installing her own appliances, Doretta is a journalist living in Vancouver and Hong Kong. She also writes poetry and fiction; her 2014 story collection How Does a Single Blade of Grass Thank the Sun? was shortlisted for the City of Vancouver Book Award, longlisted for the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award, and was named by The Atlantic as one of the best books of 2014. The title story was a finalist for the Journey Prize. It is outstanding. Its name led me to think it would be dreamy, soft-focus, lyrical. Well, no. Its splintery teenage characters and their jagged Vancouver have stayed with me (see question seven below).

At last I've coerced the superhuman Doretta Lau into discussing her new story in

Room

magazine, "Best Practices for Time Travel." When not installing her own appliances, Doretta is a journalist living in Vancouver and Hong Kong. She also writes poetry and fiction; her 2014 story collection How Does a Single Blade of Grass Thank the Sun? was shortlisted for the City of Vancouver Book Award, longlisted for the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award, and was named by The Atlantic as one of the best books of 2014. The title story was a finalist for the Journey Prize. It is outstanding. Its name led me to think it would be dreamy, soft-focus, lyrical. Well, no. Its splintery teenage characters and their jagged Vancouver have stayed with me (see question seven below). This new story has also burrowed into my mind. Porn, cities, music, race, friendship, time. I wanted to ask much more about it, but confined myself to these questions. Her thoughtful answers, like the story, make me want to whip her into finishing the novel and screenplay she's working on, and to talk with her in person.

1. Did you have any alternate titles for your story? What made you pick "Best Practices for Time Travel"? Did that come to you fully formed at the start, or later?

The working title for the story was “Flux Capacitor,” a reference to the technology in Back to the Future. I knew this wasn’t quite right, but Zoey Leigh Peterson read an early draft and mentioned that one of my characters talks about best practices and that perhaps this was the title. She was right.

2. No spoilers, but I will say that the story isn't closed. How did you find the sense of an ending?

I wrote the last line of the story early on, so I then structured the entire narrative to reach that conclusion. In order for a sense of an ending to emerge, the narrator had to experience some sort of emotional change. That’s the only way I know how to end a narrative because I don’t execute plot in a traditional fashion. The journey is across an emotional landscape, rather than a physical one.

3. This story has a backdrop of musical references, from Belle and Sebastian to Grimes. Could you choose one piece to go with the story?

I think I have to go with Taiwanese pop sensation Jay Chou’s “Twilight’s Chapter Seven” the first song from the album Still Fantasy (2006), which is referenced in the story. Chou directed the video and cast himself as Sherlock Holmes—so many levels of awesome.

4. The story is broken into numbered sections. In each, the past interferes with the present in some way--Google mistakenly reverting to the old street name of "Adolf Hitler Platz" in the first, for instance. Could you talk about that?

“What’s past is prologue”—I had to look this up to remember it’s from The Tempest. This isn’t to say that I think of the past as fate, but rather the past informs how we live in the present, how we will live in the future, and teaches us how we can change. I suppose in this story the past is a layer that lends depth and pushes the narrative towards a revelation.

The past has been on my mind a lot lately; I’ve been reading the “Survivors Speak” document from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Findings. It has been humbling to read these first person voices and to really understand the magnitude of how Canada has brutalized First Nations communities. I have been thinking about how as Canadians we’ve been complicit in these abuses and this continued injustice.

5. Racism and sexism soak these characters' lives. They laugh about it, but seem to me on the whole resigned to the system. What do you think?

I used get so angry about racism and sexism, but I’ve learned that this is unproductive. When I was in university I mocked a woman for saying that racism doesn’t exist in Canada; I wish I’d been kind enough to start a real dialogue instead of resorting to verbal pitchforking. For the story, I wanted to create characters who could talk about this kind of suffering without coming from a place of rage.

A friend just sent me an interview with the porn star James Deen where he says, “You can participate in racism without being a racist." Most of the time the people who perpetrate racism and sexism aren’t monsters. Sometimes they’re our friends, our colleagues, our neighbours and they really have no idea that their actions are so damaging. But these little things become malignant if unchecked.

6. One line resonates for me: "Sometimes the only thing you have in common with another person is a language and even that tremendous advantage is not enough." Can you talk about how this works in the story?

I was chatting to a friend on Facebook about his horrific encounters in New York. He’s a journalist from Singapore and his primary language is English, yet he’s had so many people say things to him along the lines of, “You speak such good English!” and “I had no idea you could write so well in English!” Or they just talk to him really slowly, like he’s hearing impaired or has just suffered severe head trauma. It seemed to me such an alienating experience of New York, so different from my own experience there.

After that, I started thinking that sometimes the only thing you have in common with another person is a language. I live in Hong Kong and I often encounter English speakers who seem so alien to me—I have no understanding of who they are and why they’re so bitter and unhappy when they have so much privilege. This line of thinking coincided with the narrative in “Best Practices for Time Travel”, so I decided write that sentence into the story.

7. A subtle element of fantasy creeps in. I'm always interested in the blending of reality with fiction, whether it's putting words in the mouths of historical figures or picturing the impossible. I'm thinking of another story of yours, "How Does a Single Blade of Grass Thank the Sun," which does something similar with its ending, when a small group of characters paints an enormous wall. I'm interested in your thoughts about this mix.

I have trouble writing straightforward realism. My prose becomes inert and I’m unable to create a sense of wonder. Without the element of time travel, this story would just feature four friends talking to each other during a dinner party. I rely on the fantastical to reshape how we see everyday, ordinary life. What’s there beneath the surface? What magic are we missing because we can’t see past ourselves?

Published on September 05, 2015 14:31

August 28, 2015

Storybrain: Seven Questions for Corinna Chong

Corinna Chong's new story in Room, "The Whole Animal," is a perfect example of what a short story can do with straightforward form and clarity (I'll post a link as soon as it's available online). It's a tale of bad would-be vegans who struggle with their relationship, and are nearly run down by bison in an ill-advised night trip to a national park. I swear Corinna's work flows from her in perfect shapes, but maybe that's just the effect of her calm demeanour. There's always much going on below her stories' glassy surfaces, so who knows what lurks in her?

Corinna Chong's new story in Room, "The Whole Animal," is a perfect example of what a short story can do with straightforward form and clarity (I'll post a link as soon as it's available online). It's a tale of bad would-be vegans who struggle with their relationship, and are nearly run down by bison in an ill-advised night trip to a national park. I swear Corinna's work flows from her in perfect shapes, but maybe that's just the effect of her calm demeanour. There's always much going on below her stories' glassy surfaces, so who knows what lurks in her? Corinna, like Sean Johnston from last week's Storybrain, is an Okanagan College teaching colleague and workshop collaborator of mine. Her first novel Belinda's Rings (2014), named one of the year's best by Salty Ink, is a beautifully built book about a mother who goes off to study crop circles, leaving her young daughter to pick her her messes (Corinna is also a designer--indeed, she built this very site--and that acute visual skill is evident in her writing too). She's working on another novel now, and I've read parts that have me gritting my teeth waiting for more. Meanwhile, I'm fortunate to have been able to read subsequent drafts of this great short story, and to have been able to pick her brain more here.

1. Did you have any alternate titles for your story? What made you pick "The Whole Animal"? Did that come to you fully formed at the start, or later?

I always struggle with titles. At the start of the writing process I’m not overly concerned with getting the title right, since it often takes a few rounds of revisions for me to understand what my story is really about at its heart. In the early stages my titles are just jumping-off points, so they tend to be very literal or directly linked to the story’s main plotline or images. When I finished writing the first draft of this particular story, I slapped on the title “The Bison” because the eerie image of bison faces in the rain was the part of the story that popped the most when I thought about it as a whole. But this title seemed a bit off for a story that’s really about a woman who doesn’t know herself, and is slowly being subsumed by her overbearing partner. I also wanted the title to have a link to the protagonist’s reluctant decision to stop eating meat. I had a feeling that there was a good title embedded in an early part of the story, when the character of Ward makes a round shape with his hands and the protagonist calls this “The universal symbol for animal. Whole.” Luckily, I had the chance to workshop this story with another writer who happens to be

particularly astute and a magician with titles, and after a bit of joint brainstorming she came up with “The Whole Animal.” (Who says writing can’t be collaborative?)

The rawness of this title fit the story perfectly, and I love how it conjures up questions about the opposite – the whole animal, as opposed to the broken or separated animal?

2. How did you find the sense of an ending?

I’m a sucker for stories that can pull off a circular structure, and it seemed right to try it for this story, so I thought about how I could create symmetry when writing the ending. The story begins with a cinematic description of the opening scene of a documentary film, with the frame slowly zooming out on the image of a piece of meat. I wanted the ending to echo this zooming-out feeling, except this time on a human body rather than a piece of meat. My hope was that this kind of echo in tone and imagery would solidify the parallel between the protagonist’s struggle to be a true vegan and her struggle to find her own sense of wholeness.

3. Could you choose a piece of music to go with the story?

“Doll Parts” by Hole. It’s got dismembered body parts, a dark, gritty sound, and plenty of angst.

4. The story has a primal layer (hunger of all kinds) beneath the couple's everyday surface. Can you talk about how that works here?

I think some of this comes from my apparent obsession with writing about food and eating. I often lead my characters into situations where they are forced to engage with food, and it’s only in the revision process that I realize there they are, eating

once again. I think the reason I do this is because food is so visceral for me in my day-to-day life, and so it unavoidably becomes part of my writing, too. I find that playing with the characters’ relationships to their food is a really interesting way for me to explore their conflicts. In “The Whole Animal,” Ruby is insatiably hungry for meat, while Ward seems totally unfazed by cutting meat out of his diet entirely. Meat in this story is representative of something solid, primal, simple, and real, and thus stands for a kind of authenticity and truth that Ruby longs for. I see Ruby as always hungry for something real, both physically and metaphorically, although she can’t seem to pin down what that missing thing is. Ward, in contrast, is confident in the world he has created around himself, and oblivious to Ruby’s wants and needs, to the point where his body can shrink away and yet still hold an enormous power over Ruby.

5. Your novel Belinda's Rings is very different, but also deals with a character's fascination with animals. I'm interested in where that comes from.

I’m always interested in writing about characters who don’t understand themselves, and have trouble seeing their own problems objectively or even admitting to themselves that those problems exist. I think that people who repress their problems in this way often deal with them instead by externalizing them – applying them to some other person or thing that is entirely outside of them. To me, animals act as fascinating conduits for this; while we tend to humanize them, we also see them as necessarily separate from ourselves. In both my novel and this story, the characters use their obsession with animals as a way to work out their own problems while keeping a safe distance from them. Or, maybe the animal obsession has something to do with the fact that I have a

surrogate child named Joni Mitchell who happens to be a cat…

6. And I know your novel in progress is concerned with harsh landscapes, as this story is, with the nightmarish trip to the national park. Can you talk about this?

I really admire the stories of writers like Margaret Atwood and Alice Munro that manage to make landscape so vivid and integral to their stories that it becomes another character in the drama. I’m drawn by harsh landscapes in particular, perhaps because I grew up in Calgary and have always loved the stark contrast between the gaping prairies and the craggy peaks of the Rockies. I think the

landscape that surrounds you can get into your bones, especially when it’s one that threatens you in some way.

7. Your style is very clean, contrasting the difficulties and conflicts your characters often suffer. Which writers helped build this in you, do you think?

I’m thrilled to hear it comes across as clean, because it usually feels like a giant overwritten mess as I’m writing. I hope I have learned something from Lorrie Moore, whose precision is just mind-blowing to me. The more I learn as a writer the more I focus on revising sentence by sentence, looking for the most economical and yet truthful way to convey what I want to say. Alice Munro (my hero!) and Katherine Mansfield are also masters of writing in a way that seems simple at first, but is actually so complex and carefully crafted below the surface.

Published on August 28, 2015 16:08

August 21, 2015

Storybrain: Seven Questions for Sean Johnston

I met Sean Johnston when he moved into an adjoining cubicle at Okanagan College, where we teach. I read his novel All This Town Remembers soon after, and quickly realized I was cube-sharing with a genius (he won the Saskatchewan Book Award, for one thing). We sometimes gave each other writing prompts and workshopped stories before young children took over our lives (ahem, he neglects to mention that the possible title We Don't Celebrate That came from me). Despite historical fiction not really being his thing, Sean gamely read part of an early draft of All True for me, and commented that Daniel would have been better off with a cell phone. In his version, I'm certain there would be cell phones in early frontier Kentucky.

I met Sean Johnston when he moved into an adjoining cubicle at Okanagan College, where we teach. I read his novel All This Town Remembers soon after, and quickly realized I was cube-sharing with a genius (he won the Saskatchewan Book Award, for one thing). We sometimes gave each other writing prompts and workshopped stories before young children took over our lives (ahem, he neglects to mention that the possible title We Don't Celebrate That came from me). Despite historical fiction not really being his thing, Sean gamely read part of an early draft of All True for me, and commented that Daniel would have been better off with a cell phone. In his version, I'm certain there would be cell phones in early frontier Kentucky.I always feel lucky reading Sean's work, poetry or fiction, draft or finished. It makes me think differently. It's unconcerned with keeping up a line between reality and fiction, and it is often happy to comment on itself from within. It bends the genre, but never shows off. Guy Vanderhaege calls him "a writer to watch." His latest short story collection, We Don't Listen to Them, is full of outstanding stories, which I asked him about here.

1. Did you have any alternate titles for your book? What made you pick We Don't Listen to Them? Did that come to you fully formed at the start, or later?

I considered a number of titles. I am never quite sure with collections. Novels are easier to name, I think, but this one was called at various times A Long Day inside the Buildings, We Don’t Celebrate That, Big Books Shut. All the titles I considered came from three of the stories, which seemed to be about a similar thing, but in the end I didn’t want to use one of their titles, so I chose a line from the story “Big Books Shut,” which seems okay, but still not perfect. Those stories are about the small gestures humans may make in defiance of invisible authority and the indifference with which those gestures are met, and that’s in the title.

2. Which story did you write first? How did you decide where to place it within the collection?

“A Long Day Inside the Buildings” was written first, but around the same time as “It Cools Down.” They both come later in the collection because they seem a little quieter than the others. In the first case, for instance, nobody dies, though a boy loses his foot.

The stories that complement that one come earlier, and there is more violence in them, though it’s less directly treated in ways.

3. How did you know the book was done (especially weird with a short-story collection)?

I never know that with a collection of stories. I never write stories or poems with a book in mind and I kind of regret having to put them into this artificial order. I like stories on their own as a reader too, so what happens usually has less to do with the stories in the collection and more to do with what I am writing at the time – if I find, as I did in this case, that I just wasn’t writing new stories, then I look back and collect what has happened until then.

It seems like with this one I was just working on a novel whenever I sat down to write, and had no more stories in me for a while.

4. Could you choose a piece of music to go with your book, or with a particular story?

I remember driving at night in my $800 Ford Econoline van to New Brunswick to start my MA. I had a little cigarillo, nobody else was on the highway, and one of Steve Earle’s sad leaving-town songs was on the radio, and I kind of wrote “It Cools Down” as I drove. Any of his songs, really, but especially the one that has the words “I thought I might see the first light of a new day / as it lay like fool’s gold on the ground.”

5. Your characters are often powerless or attempting to take power. Can you talk about that?

I don’t know anything else to write about, really. Wilt Chamberlain said nobody cheers for Goliath, and I think that’s true. It’s the classic problem: the world does not treat you as you would like to be treated. The world is not the world you want, and you want something else. But it’s more than that, I guess. The most compelling thing about any character, to me, real or imagined, is how they remain human despite the abuse and neglect and poverty, or whatever might happen to them.

A student of mine once wrote an amazing story in a second year class. He wasn’t the strongest writer, but his subject was by far the most compelling. His story was about a man who dreamed of a union job driving a truck at the local mine. That’s the kind of thing that interests me. It was real. I have been in that position where just getting a job as a labourer makes you feel like you’ve won the lottery, and not because you can get a new car, but because you have enough to buy a battery for the old one. That kind of thing.

6. "He Hasn't Been to the Bank in Weeks" describes a man dressing his dead wife for her funeral. Physical descriptions--bodies--in your work are usually subtle but important. Can you talk about how you see your characters this way?

I try to limit the description and provide just enough for the reader to imagine it fully. For characters and their bodies what’s important to me is where they contact the world – the gestures they make and the comfort or discomfort they feel. I hope it’s done subtly, where what little is said is a signal, because the danger is probably that movie kind of lie, where the wacky character is shown to be wacky by wearing a crazy hat or not combing their hair, etc. Or the way Brad Pitt seems to think eating while he speaks makes his character seem complex? It’s hard when there is little description, but then in short fiction I just think you don’t have the time. Maybe in novels. I don’t want to be Sherwood Anderson, say, who seems to set everything up with a short fat man vs. a long skinny one.

7. These stories aren't always obviously linked, but they frequently tread a line between the realistic and the bizarre, sometimes leaping right off that edge. Does that happen naturally when you're writing a straightforward piece?

It’s funny you say that, because so often I am wrong about which parts are realistic and which are not. I wrote, for instance, “We Don’t Celebrate That,” about Canada in the near future, where there was no freedom for writers, but there were government jobs.

This isn’t really far-fetched, of course – writers spin things for governments and businesses all the time – but now I feel like it’s actually just reality, but I made a mistake and should have written about scientists being muzzled and intelligence and science being attacked in general. I could have had a nice realistic picture of our country under Harper, but I wrote it about 6 or 7 years ago and I didn’t want to be ridiculous.

We kind of live in a world right now where I don’t think anything I have written that was meant to be absurd seems unbelievable anymore.

Published on August 21, 2015 15:38

August 14, 2015

Storybrain: Five Questions for Sean Michaels

You are no doubt aware that young Sean Michaels won the 2014 Giller Prize for his first novel, Us Conductors. I loved the title at first sight, although I confess to having imagined the book would involve buses. It doesn't. It's about Lev Termen, the inventor of the theremin, and so it's very much about music (not surprising, as Sean has been running Said the Gramophone for years, and also writes a music column for the Globe and Mail). It additionally pins down ideas of love, and of destruction and rebuilding in the twentieth century. It's told in Lev's voice, with perfect, tiny slips in English idiom that echo the story's miscommunication motifs, so I was glad to talk with Sean about first-person novels when I met him in Toronto in May. I will not forget sharing a peculiar dessert with him and his wife Thea. I'm also glad he had a little time, while sitting on a plane--this man is busy, y'all--to answer my questions here.

You are no doubt aware that young Sean Michaels won the 2014 Giller Prize for his first novel, Us Conductors. I loved the title at first sight, although I confess to having imagined the book would involve buses. It doesn't. It's about Lev Termen, the inventor of the theremin, and so it's very much about music (not surprising, as Sean has been running Said the Gramophone for years, and also writes a music column for the Globe and Mail). It additionally pins down ideas of love, and of destruction and rebuilding in the twentieth century. It's told in Lev's voice, with perfect, tiny slips in English idiom that echo the story's miscommunication motifs, so I was glad to talk with Sean about first-person novels when I met him in Toronto in May. I will not forget sharing a peculiar dessert with him and his wife Thea. I'm also glad he had a little time, while sitting on a plane--this man is busy, y'all--to answer my questions here.1. Did you have any alternate titles for your book? What made you pick Us Conductors? Did that come to you fully formed at the start, or later?

One of the first things to come to me was the title of this book. In fact I think my first draft was mostly an attempt to write the book that fit the title. But that title wasn't Us Conductors. For years the filename for this manuscript was IN WHICH I SEEK THE HEA.doc. And the title at the top of the first page was what is now the subtitle, hidden inside the final cover: In Which I Seek The Heart Of Clara Rockmore, My One True Love, Finest Theremin Player The World Will Ever Know.

A mouthful! But I imagined it in the tradition of the lengthily-titled contemporary novels that were in fashion at the time.

Then when it came time to show the book to my agent, one of her first comments was, "About that title..." I was ready for the criticism; I was already over it. And the ungrammatical Us Conductors came to me a day or two later - a riff on one of the book's most important themes, in the tone of voice of Jazz Age lovers.

2. How did you start this book--an image, a word, a general idea?

I knew I wanted to write a novel about Termen and the theremin but what crystallized the project was some opening lines. The narrator's tone of voice, his statement of purpose - hackneyed sentences that didn't survive the third draft.

3. How did you find the sense of an ending--did you know when to finish? Did the ending remain the same through different drafts?

I wrote Us Conductors from a detailed outline. I knew how I wanted to end it and that's how it ended; what changed was the absence or presence of the postscript, a vacillation about how little (or how much) to answer.

4. Could you choose a symbol to represent your book? A shape, person, piece of music, anything you like?

A woman's hand as it moves across open space, entering a field or leaving it.

5. Did the book grow out of autobiographical experience? Did writing it change your view of the past?

Since my youth I have been interested in the idea of untrue love, lying true love: the illusion that the universe is pointing you toward someone. This book helped me meditate on that; helped me put the matter to rest, perhaps, or to better understand the way a deceived, would-be lover may be responsible for their own deception.

Published on August 14, 2015 23:45

August 8, 2015

Storybrain: Seven Questions for Matt Rader

When I read Matt Rader's story collection, What I Want to Tell Goes Like This, I hear it in his voice (that's my own private answer to question six). I read at Russell Books in Victoria with him on a rainy night earlier this year (see earlier posts). The rain and the dark, and Vancouver Island and gin, turned out to be the ideal introduction to this book.

When I read Matt Rader's story collection, What I Want to Tell Goes Like This, I hear it in his voice (that's my own private answer to question six). I read at Russell Books in Victoria with him on a rainy night earlier this year (see earlier posts). The rain and the dark, and Vancouver Island and gin, turned out to be the ideal introduction to this book. The opening sentence of the first story, "The Laurel Whalen," goes like this: "It was the summer Sergeant Cote killed his only son by accident and we had to boil our drinking water." This strikes me as the whole book in miniature--the past inevitably reaching into the now, the dreadful forever tangling up with the mundane. To paraphrase the last story, "All This Was a Long Time Ago," history plots ambushes. These stories also ambush us (this is my partial answer to question five). They are startling, ominous, and highly assured. This man is a writer's writer--read the answers below!--who also has the ability to suck in readers. No spoilers, but some of these stories are guaranteed to haunt you. This book is Matt's first story collection, and his fourth book of poems, Desecrations, is forthcoming from McClelland & Stewart in spring 2016. He teaches Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia Okanagan.

1. Did you have any alternate titles for your book? What made you pick What I Want to Tell Goes Like This? Did that come to you fully formed at the start, or later?

This book took shape over the course of about 10 years and it has had many identities over that time. The first title was The North American Book of the Dead. I thought maybe I was writing a book of literary ghost stories. The current title comes from a line in the opening story “The Laurel Whalen” and only auditioned for the title role maybe six months before publication. One of the themes of the collection is, ironically, the difficulty of telling a story.

A sponsoring spirit of the book was the union activist Albert “Ginger” Goodwin. Goodwin was an orator and writer. His importance historically had less to do with his organizing efforts than with the public voice he gave to the efforts of poor and working class to collectivize. He was killed by deputized manhunters near Cumberland, on Vancouver Island, in the summer of 1918. The question that still haunts me: Who tells the story once the storyteller is dead? The title refers to the attempts the book makes to articulate that question.

2. Which story did you write first? How did you decide where to place it in the collection?

The oldest story in this collection is “Brighton, Where Are You?” which was written in 2004 or 2005. It’s a story set in a truck stop in California as a trucker tries to make his way back to Vancouver Island. When I was a kid my dad was a long haul trucker and I

remember those truck stops and the strange liminal space they occupy both civically and in the personal lives of truckers. They’re not so much passageways but eddies of time and direction in which toilets, showers, coffee, and pie appear like emissaries of settlement, transformed gifts from the “real world” that stand in for the very same things that exist at “home.” The story is placed in the collection to echo in a contemporary setting the kind of liminal moments experienced in the historical stories.

3. How did you know you were finished (especially weird with story collections)?

When my publisher took the manuscript away from me. This was my fourth book and I my experience with all of these books has been less a sense of completion than a sense of needing to move on, of having hauled the cargo as far as I could.

4. Could you choose a piece of music to go with your book?

I was gifted a vinyl record a few years ago when I was in the midst of researching the mining history that informs the collection. The record is called Come All Ye Miners and is a collection of songs performed by miners and mining families in Virginia. Part hillbilly

blues, part Appalachian bluegrass, part Americana folk that might have been from the Smithsonian Folkways archives. One song on the record—“Black Lung Blues” makes a brief appearance in the second story in the collection. Karen Dalton’s rendition of the

Blind Lemon Jefferson “Blues Jumped the Rabbit” has much the same feeling to it. Both Dalton and the miners have a sound that feels far too old to have been recorded at the very end of the 1960s.

It’s fitting for me that this is one of your standard questions as I often think of music as analogue to my writing projects. I’m currently finishing a book of poems that will be out in the spring and I’ve had two guiding records along the way, one contemporary and one classic: Hamilton Leithauser’s Black Hours and John Coltrane’s Love Supreme.

5. The book has two main threads: the stories about labour unrest in early twentieth-century BC, and those set closer to the present. Fear is a thick link between them. Can you talk about this?

To be honest, I’ve never thought too much about fear as a connective force in these stories. I’d be curious to hear more about that from your point of view. Certainly, there is an overwhelming feeling of portentousness in both the historical stories and the

contemporary ones, but I think part of the grace of the characters (in so far as I was able to describe it) is that they go one living and acting despite that sense of impending doom. To me this is the essence of deep resistance.

A critic of Anton Chekhov once said that for Chekhov the true hero was the hopeless man, who, despite his hopelessness, acts. I’d amend that a bit borrowing from a distinction that Cornel West makes between optimism as the belief that things will get better and hope as the belief that a more just world is possible: the true hero for me exists in full recognition of the portentousness surrounding our lives yet remains animated by hope. That animation is as much evidenced in simple human interactions as direct

political action.

6. Many of the present-day stories are first-person. Back to the title--who is the overall "I," do you think?

This is both a simple and a complicated question. To the complicated version: one thing that I usually spend time thinking about with my first-year students is what the self is and how we constitute our ideas of the self. This is important to both how we read and how we conceive of with whom our work communicates. Lately, I’ve been researching immunology, autoimmune disease, and the concept of the self versus the non-self that is axiomatic in almost all of Western cultural construction. We have a lot invested ethically, politically, and philosophically in these distinctions between the first, second, and third person identities.

To the simple version: the “I” is the voice speaking to you when you read.

7. You seem to trust your readers, letting us figure out for ourselves what's going on historically, switching voices within stories, and giving us what feels like very private information from some of your characters. Does this come easily?

I do trust my readers. I don’t feel like I have much of a choice. I tend to distrust experiences that have few ruptures, few intimations of mystery, few sutures of the contradictory. Which isn’t to say that I don’t enjoy the well-made work of art or the well-curated experience, because that would be ridiculous and disingenuous. But for me those works of art, those experiences, take their charge from their irreducibility, the impossibility of paraphrase, from the moments of wilderness in which I am invited to find my own way. The craft is in offering the opportunities for navigation._

Published on August 08, 2015 07:05

July 31, 2015

Storybrain: Five Questions for Adam Lewis Schroeder

Adam Lewis Schroeder has three names, and is unafraid to use them all. He is my smart friend and fast-and-furious writing workshop collaborator, as well as the author of three novels and a short story collection, Kingdom of Monkeys, which was shortlisted for the Danuta Gleed Award. His two first novels, Empress of Asia and In the Fabled East, are both luxuriantly detailed historical works, and on many book-of-the-year lists, as well as Amazon First Novel and Commonwealth Regional Writers Prize finalist rosters. His latest, though, is something else. All Day Breakfast is all zombies, all the time, with a side of bacon. In Nebraska. It's already been named one of Amazon.ca's best books of the year to date, and Adam is headlining the Kelowna Fan Expo in March 2016.

Adam Lewis Schroeder has three names, and is unafraid to use them all. He is my smart friend and fast-and-furious writing workshop collaborator, as well as the author of three novels and a short story collection, Kingdom of Monkeys, which was shortlisted for the Danuta Gleed Award. His two first novels, Empress of Asia and In the Fabled East, are both luxuriantly detailed historical works, and on many book-of-the-year lists, as well as Amazon First Novel and Commonwealth Regional Writers Prize finalist rosters. His latest, though, is something else. All Day Breakfast is all zombies, all the time, with a side of bacon. In Nebraska. It's already been named one of Amazon.ca's best books of the year to date, and Adam is headlining the Kelowna Fan Expo in March 2016.Well. Not my usual reading matter. But I'm awfully glad I picked it up. This book manages to be crazily funny, with lots of graphic-novel-style fistfights and loss of limbs, with an undertow of deep sadness, and the same intensity of detail Adam uses in his earlier books. Not easy to pull off, but he did it. Here is a bit about how:

1. Did you have any alternate titles for your book? What made you pick All Day Breakfast? Did that come to you fully formed at the start, or later?

No. My first thought for the book was to have sentient zombies who crave bacon rather than brains, and my next thought was to call it All-Day Breakfast. But! I did have a planned epigraph from Dr. Seuss's "I Had Trouble in Getting to Solla Sollew":

This is called teamwork. I furnish the brains.

You furnish the muscles, the aches and the pains.

I'll pick the best roads, tell you just where to go

And we'll find a good doctor more quickly, You know.

I approached Random House and the Seuss estate for permission a year before publication, it was fairly easy because they get so many queries there's just a webpage to fill out, but I still haven't heard back. So no alternate title, but there is a failed epigraph.

2. How did you start this book--an image, a word, a general idea?

The idea came one evening when I was reading a Walking Dead graphic novel from the library (before the TV show!) and my wife Nicole was reading a Jack Reacher thriller. Reacher is an ex-military problem-solver, traveling the Midwest, kicking doors down, and I started asking Nicole, because I was tired and ought to have been going to bed, how he might operate differently if he were a zombie. Apparently Reacher eats a stack of bacon with his breakfast every morning, so that partly answered the question--a composite zombie would eat bacon instead of brains. A night or two later I wrote the scene which is now at the bottom of page 199, where his leg is coming off at the knee so he stumbles into a shed on a farm and is able to nail it back on, then a sexy girl in a T-shirt knocks him out with a frying pan. Initially he was thinking a lot about his kids while he nailed his leg back on, which established an inner life, and though there are no longer kid thoughts in that particular scene they're pretty much everywhere else. The voice, tone and plot did not change from those initial paragraphs, so in hindsight I think I won a prize.

3. How did you find the sense of an ending--did you know when to finish? Did the ending remain the same through different drafts?

The end of the first draft is now halfway down page 332. My editor Barbara Berson felt the plot then was pretty good but the reader deserved more time with the students, so there was a heavy rewrite which inserted the students much deeper into the story, and brought some of them back in a new scene at the end, which made page 345 the ending. Then in a final draft I increased the scope of the background story, which again didn't add much material to what was already written but tacked on a 32-page epilogue. Which was SO FUN to write.

4. Could you choose a piece of music to represent this book?

"Indiana Wants Me," R. Dean Taylor, 1970, is narrated to his wife, which mirrors lots of sections in the book, detailing how much he misses her and and their kid while the law hunts him through the Midwest for a crime he was right to commit.

As a kid I found it wonderfully earnest and moving, now I additionally see it as a pop gem with police-siren sound effects. (I just found this YouTube link where an offscreen host, incredibly, addresses his viewers as "zombies.")

5. Did the book grow out of autobiographical experience? Did writing it change your view of the past?

The protagonist's wife dies of cancer six months before the opening of the novel, while my dad had died of cancer a year before I started writing.I hadn't realized how fucked up and angry I was over his death until I started having Peter do one fucked up, angry thing after another. Traditionally zombies just shuffle around with their ill intent, but my protagonist unexpectedly held a mirror up to me and threw televisions through windows and smashed bird houses into tiny pieces. More like a very sad human person.

Published on July 31, 2015 12:28