Jim Auchmutey's Blog, page 3

May 11, 2016

Baptists, barbecue ... and a famous writer

I learned about Koinonia when I was working for Presbyterian Survey, the denominational magazine in Atlanta. The editor, Bill Lamkin, was skeptical when one of our free-lancers, Lynn Donham, suggested doing a story on the religious community in southwest Georgia. Bill thought Koinonia sounded a little too Baptist for a Presbyterian publication. But Presbies are pretty ecumenical, and he relented and let us do the story, which started me on the path to writing “The Class of ’65.”

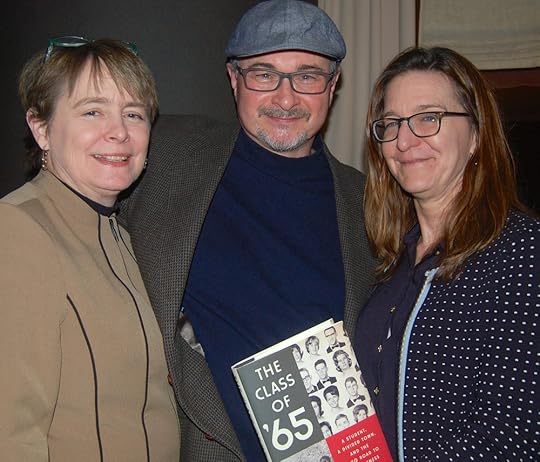

I mention all this because Bill’s widow, Jane Lamkin (shown here), is a dear friend and has been very supportive of the book. Not only did she suggest that I speak about “Class” at Northside Drive Baptist Church in Atlanta last fall (where the pastor, James Lamkin, is Bill’s nephew), but she also invited me to her house recently to talk with her book club. Knowing me well, she catered the event with barbecue from Heirloom Market, one of Atlanta’s best barbecue places.

The book club is called the Pi Phi Reading Angels (!!!), and it’s comprised of members of the sorority Jane joined in college. What an interesting group of women; Pam and I enjoyed meeting them very much.

Before we left, Jane asked me to sign a couple of books. One of them, she said, was for Anne Tyler.

Anne Tyler? I said. The novelist who wrote “The Accidental Tourist” and many other good books?

It turns out that Bill, who worked for Friendship Force after leaving the Presbyterian magazine, was returning from a trip to Russia many years ago when he met a couple over lunch during a refueling stop in Greenland: a Mr. and Mrs. Tyler. They mentioned that they had a daughter who was a writer. “Would that be Anne Tyler?” Bill asked.

The Lamkins met the Tylers again during a reunion of that Friendship Force exchange with Russia, and Jane asked for their daughter’s address. The two of them have been corresponding since 1983, Anne answering Jane’s letters in a diminutive hand on stationery with embossed initials.

I was honored to sign a book for such a distinguished writer, honored that Jane would ask. Thanks for your friendship, for your support -- and for the excellent barbecue. I think Bill, my first boss and a good and gentle soul, would be pleased.

April 25, 2016

Janey and Flannery

I was especially pleased to speak about "The Class of '65" last week at Georgia College and State University in Milledgeville because it's my mother's alma mater. Janey Yarbrough graduated in 1945 when the school was known as the Georgia State College for Women. The students called themselves Jessies (after GSC) and their little college town Jessieville.

In preparation for my talk, I pulled out my mother's yearbook and was reminded that one of her classmates was perhaps the college's most famous graduate: an aspiring writer named Mary Flannery O'Connor (or O'Conner, as they spelled it in the senior section -- apparently a good proofreader was hard to find). She was known more for her cartoons then, and they filled the annual with her quirky illustrations of campus life, like the one shown here. Mother remembered her as being kind of an odd duck. An odd duck who blossomed into one of the true peacocks of Southern literature.

I was the guest speaker for the History and Geography Department's honors day program, the closing act for an impressive display of student accomplishment and faculty guidance. Many thanks to department chairman Aran MacKinnon for inviting me, to history professor Craig Pascoe for suggesting me, and to all the students and professors who gave me their attention and asked good questions after I had talked about my modest contribution to Georgia history.

Pam and I were happy to see in the audience my Uncle Moon (birth name: Arthur Yarbrough), a retired college professor himself; his friend Ruth; and my Cousin Dyann, who all drove over from Sandersville and environs. Our longtime friend Ginger Rudeseal Miller, who was on the Georgia State University newspaper with us and taught journalism for years at Georgia College, came as well and joined a group of us for dinner afterwards (where this photograph was taken). It was great seeing Ginger again.

If you haven't been through Milledgeville lately, you might be surprised by what a lively college town it has turned into. My mother would be thrilled to see what has become of her old school -- and of the place they used to call Jessieville..

April 1, 2016

Has it really been a year?

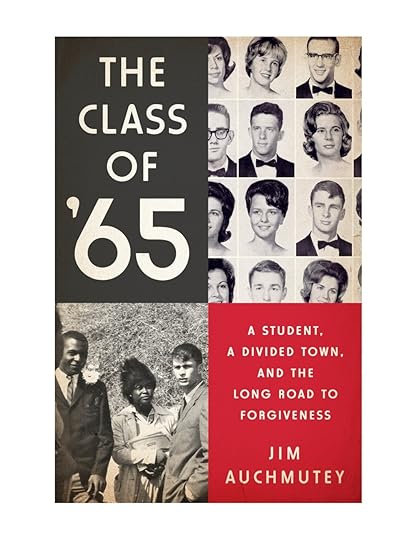

One year ago this week, I took the stage at the Carter Library in Atlanta and gave the first talk about my book “The Class of ’65.” I was nervous because I never expected to look out and see an overflow crowd of 250 people -- an audience that included friends, family, former colleagues and quite a few people who figured in the book. Chief among them was Greg Wittkamper, whose ordeal at Americus High School during the 1960s forms the spine of the story. By the time I invited Greg up to the microphone to talk and answer questions, my stage fright was a thing of the past.

In the year since “Class” was published, I have given scores of talks to civic groups, literary festivals and book clubs. I’ve done so many media interviews that I lose track -- including, most recently, a flurry of radio interviews with NPR affiliates during Black History Month (New York, Washington, Boston, Miami, Minneapolis, Memphis, Birmingham … and many more). The book was well-reviewed by The Washington Post, the AJC, The Christian Century and the Associated Press, whose glowing praise was picked up by more than 100 outlets across the country and in Canada, Australia and New Zealand. I’ve been on C-SPAN and excerpted in Salon. Most books don’t get a fraction of this publicity; I can’t complain.

With so much attention, you might think that “The Class of ’65” was destined to become a best-seller. Not exactly. Writing a nonfiction narrative set in the civil rights era is not the surest path to publishing success. The book has sold respectably, but the only time it has made a best-seller list was when it appeared in The New York Times roster of books about Race and Civil Rights last spring. “Class” was No. 11: “also selling.” A sorta best-seller in the NYT -- we take what we can get.

Of course, I didn’t write this book because I thought it was going to sell a million copies. I wrote it because (1) I wanted to learn how to create a nonfiction book, and (2) I believed in the story and wanted it to gain a wider audience. I want people to know about the persecution of Koinonia, that band of Christians who believed in brotherhood and nonviolence when those were dangerous concepts. I want people to know about the civil rights struggle in southwest Georgia, which never gets as much attention as events in Selma and Birmingham. I want people to know about what Greg and the other Koinonia kids endured in high school. Above all, I want people to know about the remarkable reconciliation set into motion by Greg’s classmates, who grew to regret the way he and others had been treated.

A number of readers have told me that without that last element, this book might have been too painful for them to finish. I see their point. Without forgiveness and reconciliation, we have nothing. With them, we have hope.

Thank you so much to all the readers who have opened their hearts to this story. I especially thank Greg and his classmates -- white and black -- who lived this drama and allowed me to tell it. This experience has been so fulfilling. I will continue to do everything I can to help “The Class of ’65” find its audience.

March 23, 2016

Virginia is for book lovers

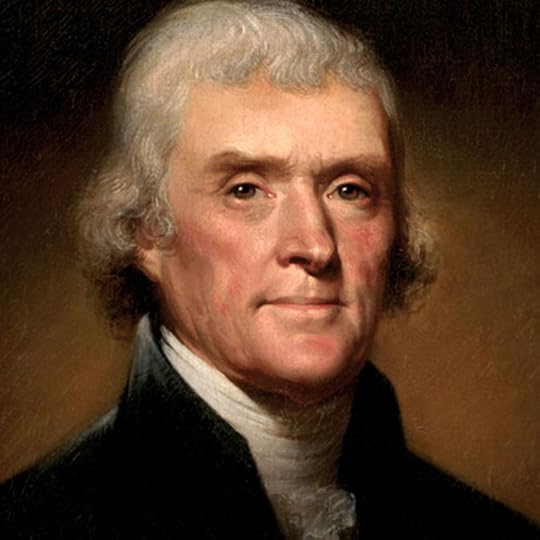

It’s intimidating to speak about your own humble attempt at eloquence when you’re in Charlottesville, Va., home of Thomas Jefferson, who wrote some of the most eloquent words ever composed in the Declaration of Independence. But I did my best last weekend at the Virginia Festival of the Book, where I was invited to make a presentation about “The Class of ’65.”

I shared the stage with Kristen Green (seen with me below), an accomplished journalist who wrote “Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County,” a first-person history about growing up in the southern Virginia county that actually closed its public school system rather than desegregate. I haven’t read it yet, but it sounds fascinating.

When it was my turn to speak, I looked down at the front row where my main character, Greg Wittkamper, sat with his wife, Anne, and their daughter, Sallie. Greg lives a couple of hours away in West Virginia and had come to the festival with two in-laws: Anne’s sister, Sallie, and her husband, Gary. Mindful of Greg’s traumatic experiences at Americus High School, I started with a rueful joke, saying that if he had known all the abuse he was going to suffer, he might have preferred that officials in Georgia close his school system like the people in Virginia.

The session was held at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center, a handsome redbrick building in downtown Charlottesville. I expected the crowd would be more interested in Kristen’s book, being closer to home, but there were as many questions about my story, even though it’s set hundreds of miles away in Georgia. One woman had actually spent time at Koinonia, the farming commune where Greg was raised. Another audience member knew all about the story because, well, she was a former colleague of mine at the Atlanta newspapers: Emma Edmunds. She left Georgia almost 20 years ago to return to her native Virginia and has done groundbreaking research into the civil rights movement there. It was great seeing Emma again. (My wife, Pam, took this picture of us after brunch the next morning; she must have said something that tickled us.)

Many thanks to the people at the Virginia Festival of the Book for a wonderful weekend. Thanks to Kristen Green for sharing the spotlight so graciously and to our moderator, Amy Tillerson-Brown, a history professor at Mary Baldwin College who grew up in Prince Edward County and knows this material in her bones.

Oh, and thanks to Mr. Jefferson for writing those beautiful words about freedom -- although it took America a long time to realize what they fully meant.

February 2, 2016

My youngest editor

During my recent trip to West Virginia for King Day, I was asked to speak to a couple of classes at the Greenbrier Episcopal School, where Greg Wittkamper and Anne Gardner’s daughter, Sallie, is in the eighth grade. A number of the students have aspirations to write or tell stories in some other media, and they wanted to hear from someone who has made a living out of banging verbs and nouns together.

Frankly, I don’t know how they could even understand me on that frigid January morning. I had a cough and the stirrings of a head cold, and my voice was so low and croaky that I could have sung bass for a gospel quartet. But I soldiered on, and Greg and I told them about the story behind “The Class of ’65” (his tale, mostly) and how it came to be a book (my tale, mostly).

At one point, Greg asked me to tell everyone about the volunteer editor who changed one of the chapter titles. That would be Sallie, his youngest daughter, who was part of our audience. Sallie must have been all of 13 when she read the manuscript, which details the trials her father went through in Americus, Ga., as he grew up at Koinonia, the embattled Christian farming commune, and braved constant abuse at Americus High School during its desegregation. The shortest chapter of the book concerns the day when a large pack of Greg’s classmates confronted him after school and one of them punched him in the face. My unimaginative title for the chapter? “The Fight.” Sallie read it and suggested an alternative: “Still Standing.” Her title was more accurate, more intriguing and better in every way. I changed the name of Chapter 8 without hesitation. Thank you, Sallie.

I was impressed that these students sincerely wanted to hear what it takes to tell a story in book form. I hope they were inspired by the knowledge that one of their own had an impact on “The Class of ’65.”

Thank you to Birch Graves and Carrie Bailey, the teachers who invited Greg and me to speak to their classes, and to all the students who listened to us and then, as we were leaving, came up and hugged us one by one. Well, all except for the boy who gave me a fist bump. I understand: A dude’s gotta be cool.

January 27, 2016

Conrad Browne, 1919-2016

One of Koinonia’s early stalwarts and an important figure in my book, “The Class of ’65,” has died: Conrad Browne. He was 96 and lived in Warwick, Rhode Island.

Con Browne was a Baptist minister fresh out of the University of Chicago when he heard Clarence Jordan speak about Koinonia at a conference. He was so captivated that he persuaded his wife to move to south Georgia in 1949 to become part of the communal farm, even though he knew nothing about tending chickens or growing crops.

Con was one of the leaders of Koinonia during the years when it was boycotted and terrorized for its belief in racial brotherhood. He was in charge of the egg delivery route and saw firsthand how local businesses were boycotting the farm. During the height of violence against the community -- the drive-by shootings and bombings -- Con was attacked in Americus by a man who bashed him in the face simply because he was from Koinonia. The sheriff responded by charging Con, still bruised and bleeding, with a traffic offense.

I flew to Rhode Island to meet Con in 2007, joined by Greg Wittkamper, my main character. In our two days of interviews, I could tell how much affection they had for each other. Greg regarded him as a surrogate father and confided later that it was Connie (as he called him) who had told him about the birds and the bees. As we sat in his home on Narragansett Bay, I asked Con why his family had left Koinonia in 1963. “Do I have to?” he said with a pained expression. The farm was hurting economically and could no longer support very many residents, he explained, and the adults decided that the Brownes should go. Con took a job as associate director of the Highlander Center in Tennessee, the place where Rosa Parks had received training in nonviolent resistance. It was a worthy post, but you could tell that it still hurt him after all those years to think about leaving a place he loved so dearly.

My deepest condolences to Con’s wife, Cay, and to his four surviving children, three of whom (Lora, Charles and John) appear in “The Class of ’65.” Conrad Browne was a good man who practiced his faith even when it was dangerous to do so. May his soul know eternal peace.

January 20, 2016

King Day in a cold place

When I was working on “The Class of ’65,” I adhered to the agreeable weather school of historical research. I tried to visit Americus and Koinonia when it wasn’t so hot and sticky and gnatty in southwest Georgia. That was the best time to go to West Virginia to see the focus of my story, Greg Wittkamper. Until this past weekend, I had never been to the state during the dead of winter.

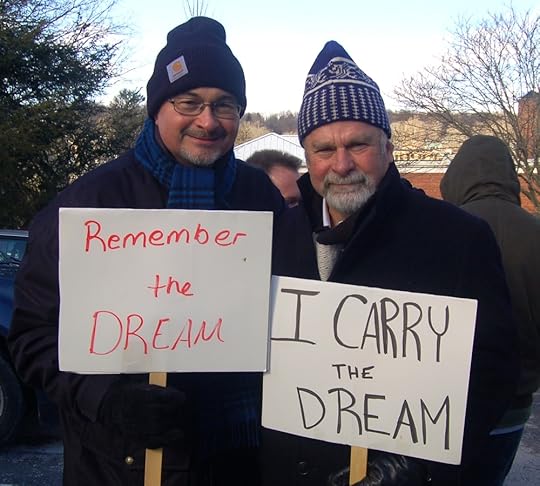

Then they invited me to be the keynote speaker at the King Day program in Lewisburg. W.Va., a beautiful community near the Greenbrier Resort that bills itself as “the coolest small town in America.” Cool: as in charming and bohemian, not as in single-digit temperatures.

King Day 2016 began, as King Days must, with a walk from a courthouse to a church. It was 9 degrees, with patchy snow and ice from a storm the night before (which is why Greg and I are dressed like Eskimos in the photo). Considering the frigid conditions, a respectable crowd of a couple of hundred made the trek, which was rewarded with bowls of chili and cups of hot chocolate at Lewisburg United Methodist Church.

The service afterwards was multifaceted, to say the least, with hymns, a dance recital, student essay readings, a drum corps and a soaring rendition of “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” by a local pastor, Kathie Holland, who pointed out that Mahalia Jackson had performed the song at King’s funeral in 1968.

And then it was my turn. I told the assembly a little about what it had been like to cover the first King Day celebration 30 years ago this month in Atlanta, where I was a reporter for the Journal-Constitution. How no one knew quite what to make of the new holiday, which was marked with a parade and marching bands like it was a wintertime version of July the Fourth.

Most of my talk centered on the connections between Koinonia and the civil rights movement, both of which were terrorized for their commitment to brotherhood. At the same time King and participants in the Montgomery Bus Boycott were being targeted in Alabama, Koinonia was being boycotted, bombed and shot at in Georgia. I read from a letter King sent to Clarence Jordan as the two Baptist ministers were commiserating over what their people had to endure because of their beliefs: “You and the Koinonia Community have been in my prayers continually for the last several months. The injustices and indignities that you are now confronting certainly leave you in trying moments. I hope, however, that you will gain consolation from the fact that in your struggle for freedom and a true Christian community you have cosmic companionship.”

I also spoke of the civil rights movement in Albany and Americus, about Koinonia’s support for it and the involvement of the farm’s young people. Greg attended a good many of the mass meetings at black churches in both cities and took part in several marches. I love the photo below showing Greg in a column of protesters in Americus; he's the only white face in the crowd, near the left. Those Koinonia kids certainly stood out. But Greg was no braver than the others stretched out along the street that day in July 1965.

Thanks to the MLK Day committee in Lewisburg for inviting me to speak (Larry Davis and others) and special thanks to Greg and Libby Johnson (and Sadie) for lodging and feeding me in their beautiful warm home.

January 8, 2016

Justice is served

My first talk of 2016 was before the Lawyers Club of Atlanta’s fiction book club -- which was a little confusing since “The Class of ’65” is nonfiction. Apparently, they read a true story every year. Lawyers should never stray too far from facts.

As we were discussing the book in a 38th-floor board room with a gorgeous view of Midtown Atlanta, I brought up a legal angle I thought might interest this group. If it hadn’t been for a federal lawsuit, the narrative I focused on in “Class” might never have happened.

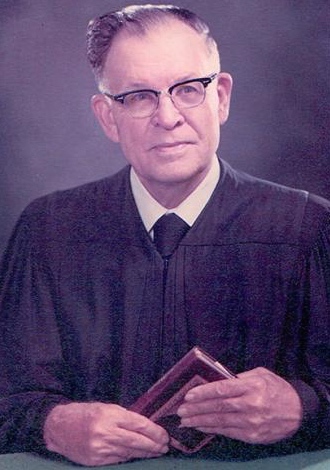

The lawsuit was William Wittkamper et al. v. James Harvey et al. and the School Board of Americus, Ga. Koinonia parents filed the suit in the fall of 1960 when the city school board refused to admit three of their children because they thought having students from the communal farm would produce conflict and unrest at Americus High. Judge William Bootle (above) recognized religious persecution when he saw it and ordered the schools to admit the Koinonia children. Bootle was hanged in effigy in Americus, in part because of that ruling and and in part because of an even more controversial decision he issued a few months later, ordering the University of Georgia desegregated.

The students who entered Americus High that fall were Jan Jordan, Lora Browne and Billy Wittkamper. A year later, Billy’s brother Greg Wittkamper -- my main character -- began at the school. All of them were treated terribly because of their unpopular beliefs, an ordeal which forms the heart of the book . And none of it would have unfolded without the strong arm of the federal judiciary.

Thanks to the Lawyers Club for inviting me, and special thanks to my friend Katie Wood for hosting the event. That’s Katie on the left, with our friend Chris Smith. We've all played poker together for years -- but that's another story.

December 24, 2015

Christmas 1965

Here’s a short Christmas story from “The Class of ’65” that shows something we can be thankful for. It happened 50 years ago this month in a time and place that seems familiar yet so far away.

A group of people from Koinonia drove into Americus to hear a visiting minister speak at the largest church in town, First Baptist. Among them were the community’s leader, Clarence Jordan; a couple of newcomers, Millard and Linda Fuller; and a recent high school graduate soon to leave for college, Greg Wittkamper, the main character of my book. One of Greg’s best friends was with them, too: Collins McGee, a civil rights activist who worked at the farm. Collins (as you can see in this photo with Greg) was black.

As the Koinonia party entered the church, an usher became visibly alarmed at the sight of a black hand reaching for a bulletin.

“Who’s he?” he asked.

“Why, that’s Collins McGee,” Greg answered innocently.

The congregation was singing “It Came Upon a Midnight Clear” as the Koinonians took their places in a pew. Just as they came to the line about “peace on Earth, goodwill to men,” the usher hurried over and grabbed Collins by the collar.

“You’ve got to get out of here,” he commanded.

The Koinonians knew First Baptist was segregated, but they had hoped that their interracial group would be allowed to join the worship service in the spirit of the season. Not a chance. They left peacefully. Outside the sanctuary, Clarence looked back at the church and was struck by the way its white columns and floodlit steeple stood out against the vast night sky. He reached for a preacherly metaphor. “I want you to notice,” he told everyone, “how much darkness there is.”

I heard this story from two different participants a quarter of a century apart. Millard Fuller first told it to me in 1987 when I was writing a profile of him and his work as one of the founders (with his wife, Linda) of Habitat for Humanity, the housing ministry that traces its roots to Koinonia. Years later, when I was working on “The Class of ’65,” Greg Wittkamper told me the same anecdote as we were sitting on his deck in the mountains of West Virginia. The experience of being turned away from a Christian church because one of their party was black left a deep impression on them. But they weren’t surprised. Despite the new civil rights laws, that’s the way things were in Americus and many other places in America.

I’ve thought of this story several times this year as I’ve spoken about my book. A good many people have asked whether I think race relations have really improved since the 1960s. It’s a legitimate question. When every month brings news of confrontations with police and hate crimes and more rancor and distrust, you have to wonder.

I’m retelling this Christmas tale now because it shows in its small way what things were like not too many years ago. It also shows how things that once seemed immutable do change. That church eventually dropped its restrictive policies when its membership realized that exclusion was not in keeping with their faith.

Clarence was right: There’s a lot of darkness out there. But there’s also light, and most of us, when we search our souls, are drawn to it. For that, we should be grateful.

Merry Christmas, everyone. Peace be with you.

November 5, 2015

David Wittkamper, R.I.P.

I received some sad news this morning: David Wittkamper, one of Greg’s brothers, died of cancer overnight in West Virginia. He was 65.

David plays a vivid supporting role in “The Class of ’65.” He was the third of the Wittkamper boys, three years younger than Greg, and just starting school when the terror campaign against Koinonia began during the 1950s. David attended Americus High School for one year and then left because of the constant bullying and occasional physical abuse, continuing his education with family in Indiana. It was in David’s class in Americus that some students cheered the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

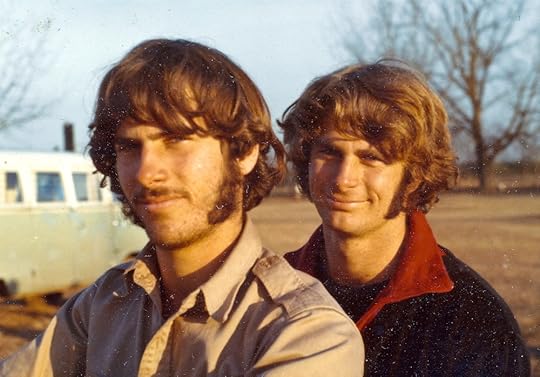

Greg and David were very close. When Greg returned to Georgia in 1969 after his travels with Friends World College, the two of them hopped on a motorcycle together and trekked out west and down to Central America. (The photo above shows them as they get ready to embark; that's David on the left.) Both were conscientious objectors during the Vietnam War and did their alternative service at the Friends World campus on Long Island. A few years later, they settled near each other in southern West Virginia, where they made their living with their hands, like a couple of farm boys, building barns, digging wells and such.

David always struck me as the quintessential latter-day hippie. When I met him, he was pushing 60 and still wore his hair in a pony tail. He distrusted authority with the conviction of someone who had grown up in a time and place where authority truly could not be trusted. He was a sensitive soul with a sweet disposition. Like Greg, he often teared up when he spoke about the things he and the others at Koinonia went through when they were young.

A couple of years before he fell ill with bladder cancer, David built a tree house on his property -- not a little playpen, but an aerial bungalow in a sturdy tree that he wanted to rent out and invite his friends to stay in. When he showed pictures of it in the binder he used to carry around, his face lit up with pride. I’d like to think of David sitting in that treehouse now, looking over the rest of us with a smile.

David is survived by his wife, Teresa, and his sons, Wesley and Jonah.

Greg Wittkamper with his brothers David (right) and Dan (front) at a Koinonia reunion in 2012. Their older brother, Bill, who lives outside Chicago, was not able to make it.