Jim Auchmutey's Blog, page 2

July 29, 2019

Barbecue homecoming

I was barely 2 when my grandfather died, so I never really knew Bob Auchmutey (or "Daddy Bob," as the family called him). But I knew him by reputation, and an important part of his memory was a July 1954 article in the Saturday Evening Post titled "Dixie’s Most Disputed Dish." The story was set at the Euharlee Farmers Club barbecue, where my grandfather oversaw the pits and stew pots. I’ve mentioned it a few times since "Smokelore" was published.

Well, Trey Gaines, the director of the Bartow History Museum, saw one of those interviews and invited me to come to Cartersville to speak. Of course, I said; it’d be like going home.

I was expecting maybe 40 people to show up for the lecture late last week. There were more than twice that many — so many they had to move the talk next door to the much larger auditorium in the Booth Western Art Museum.

It was a pleasure to speak about barbecue history and my family’s connection with it in a place where some people had personal memories of my grandfather back when he ran community barbecues in the Etowah River valley. See that second photo below? I’ve always wanted to identify all the men in this portrait of Bob Auchmutey’s pit crew from about 1956. That’s my Uncle Earl on the left and Daddy Bob second from right, holding the butcher knife. I don’t know who the three others are, but I have some good leads now from people I’ve met in person and online in Bartow County. (If you think you recognize one of them, please contact me.)

My talk in Cartersville was one of the most personal and memorable evenings I’ve spent in promoting "Smokelore." Many thanks to the Bartow History Museum, Scott’s Walk-up Bar-B-Q (a great barbecue place in Cartersville that catered the event) and the Booth Western Art Museum. I think Daddy Bob would have been proud. I’m proud of him.

July 12, 2019

Pat Conroy and me

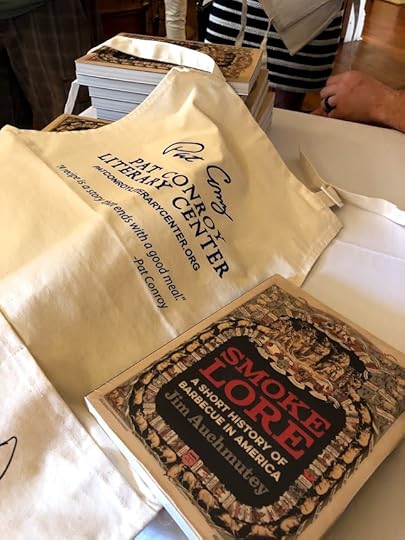

I’ve owed Pat Conroy lunch for some time, so I was happy to more or less repay the debt last weekend by speaking about my barbecue history, "Smokelore," at the Pat Conroy Literary Center in Beaufort, S.C. I’ll explain.

Thirty years ago, after I wrote a series of articles about discrimination in private clubs for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, I answered the phone at my newsroom desk and heard laughter. It was Conroy, then living in Atlanta and basking in the glory of his best-known novel, "The Prince of Tides," soon to be a movie starring Barbra Streisand and Nick Nolte. The man was at the peak of his career, and he had time to phone a reporter and tell him he liked his story.

He was laughing because I had quoted a member of one of Atlanta’s most prestigious clubs as saying that he liked Jews OK but wouldn’t want to invite one into his home.

"How’d you get him to say something like that on the record?" asked Conroy, who knew the guy.

"I called him after 5," I replied. "I think he’d begun happy hour."

Conroy laughed again and said he’d like to take me to lunch. And so we met over a meal, the famous novelist and the unfamous reporter.

Thirty years later, the Pat Conroy Literary Center invited me to South Carolina to speak about my new book, "Smokelore: A Short History of Barbecue in America." Conroy died in 2016 of pancreatic cancer, and his family and admirers founded the center, a museum and institution that promotes reading and writing, as a way of continuing his passion for storytelling. I readily accepted because, well, I owed him lunch.

It was a great weekend in the Lowcountry. The Conroy Center partnered with the Anchorage 1770 inn to host a barbecue talk and meal in their historic perch overlooking the waterfront in downtown Beaufort. Chef Byron Landis smoked some pork, brisket, chicken and snapper and made six sauces from the book for guests to sample. I spoke while everyone nibbled and tippled. Then we signed books and aprons.

Many thanks to the Conroy Center (Maura Connelly, Jonathan Haupt and Kathy Harvey — Pat’s younger sister), to the Anchorage 1770 (Amy and Frank Lesesne and Chef Landis) and to Debbi Covington, a Beaufort caterer and cookbook author who helped out with the meal. It was fun.

After the talk, there was just enough daylight left for my wife, Pam, and me to drive to neighboring St Helena Island, where Conroy is buried in a church graveyard near the Penn Center, the Gullah cultural center that was the site of many retreats and meetings during the civl rights movement. Conroy’s marker wasn’t hard to find under the branches dripping Spanish moss; his signature is engraved in the tombstone, and his plot is covered with pens and pencils and tennis balls and other tributes visitors have left.

As I stood there, I thought about a Conroy quote I used in "Smokelore." It comes from the mouth of Tom Wingo, the protagonist of "The Prince of Tides": "There are no ideas in the South," Tom says, "just barbecue."

We definitely have barbecue in the South. But I think we have a few ideas, too. Look at the words of Pat Conroy.

May 24, 2019

Barbecue showtime!

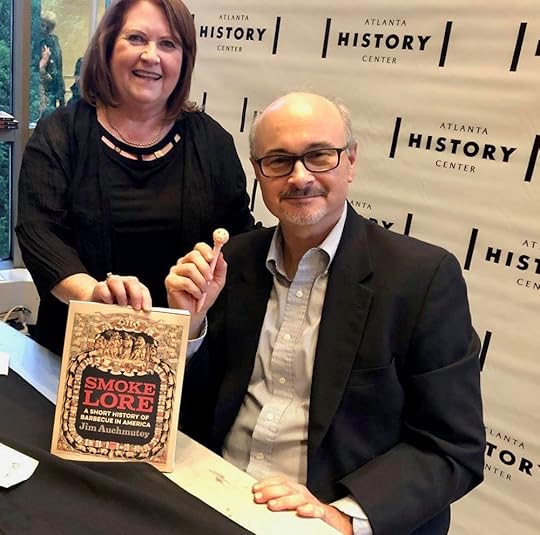

This is my first post in a while, and I’m switching gears to my new book, “Smokelore: A Short History of Barbecue in America,” which had its launch last night at the Atlanta History Center. What a great evening. A standing-room-only crowd came for a reception catered by Atlanta’s DAS BBQ (I’m sure it was tasty, but I was too busy to get any, dammit). Then the program began, with Sheffield Hale, the center’s CEO, introducing me.

The History Center started this book rolling a decade ago when they asked me to help advise on an exhibition about the great American institution of barbecue. Then they asked me if I’d like to do the companion book, to be put out by their publishing partner, the University of Georgia Press. I ended up writing the book and helping to curate the exhibition, “Barbecue Nation,” on view at the Buckhead museum through Sept. 29.

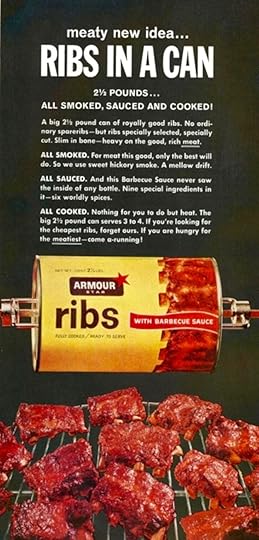

My talk was basically a slide show with a lot of anecdotes and funny asides. It couldn’t have gone better. Well, I do wish that picture we showed of Homer Simpson standing at a grill had more accurate color. On the projection screen, his skin was green, like he was a Martian instead of bright yellow cartoon character. On the other hand, when I showed a 1964 ad for Armor Ribs-in-a-Can (yes, they really sold ribs in a can, like dog food), no one who had just eaten the real barbecue barfed. For that, I am grateful.

Many thanks to the History Center, the University of Georgia Press, and the many friends (like Alice Murray, shown with me at the signing table), family members and barbecue people who came out for the debut event. It was special.

July 11, 2017

The church that stayed true

When I asked the audience at Central Presbyterian Church how many of them had ever heard of Koinonia, almost all the hands went up.

No surprise there. Central has a long tradition of social activism. This was one of the downtown churches that welcomed the thousands of people who crowded Atlanta for Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral in 1968, in stark contrast to the State Capitol across the street, where Gov. Lester Maddox ringed the grounds with troopers and refused to lower the flag in respect for the passing of such a distinguished native son. The Presbyterians opened their sanctuary and offered shelter and sustenance to the throng of mourning pilgrims. In other words, they behaved like Christians.

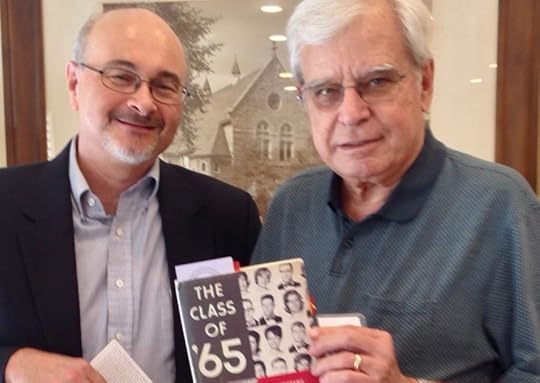

Knowing some of that history, I was honored when Central invited me to speak about “The Class of ’65” at its summer studies series before the regular worship service this past Sunday. Gary Rowe, a former neighbor of ours and a veteran of church communications, asked me to come. One of the nicest things about writing a book is reconnecting with old friends you’ve fallen out of touch with like Gary (shown with me in the photo).

One of the other nice things is meeting new friends. One of them, Frances Padgett, said that her grandfather had arranged the sale of the farm property in Sumter County to establish Koinonia in 1942. Small world indeed.

Thank you, Central Presbyterian, for being such a warm and knowledgeable audience. That after-worship lunch was pretty good too.

February 16, 2017

Sacred ground

Many people don’t know that Jesus was born in Gainesville, Ga.

When I spoke about “The Class of ’65” earlier this week at the Cresswind community in Gainesville, I began my talk with this unusual bit of latter-day biblical scholarship. It comes, of course, from the Cotton Patch gospels, Clarence Jordan’s retelling of the New Testament in the Southern vernacular. Jordan co-founded Koinonia, where my story is set, so it seemed fitting that I tell my listeners we were on sacred ground.

In the Cotton Patch version, Mary and Joseph are headed to Gainesville to see about a tax matter when Mary goes into labor pains. The couple pull over at the Dixie Delite Motor Lodge, but there aren’t any rooms, so they take shelter in an abandoned trailer out back. The baby is born, swaddled in a comforter, and laid in an apple crate.

This was my first talk since November. I’ve been very busy the past few months finishing my next book, a history of barbecue for the University of Georgia Press. As I took the podium, I was afraid that I’d start blathering about wet ribs vs. dry ribs, but I needn’t have worried: I fell back into Koinonia and Americus High and Greg Wittkamper and his classmates like I’d never left them.

It was a great audience: about 70 people representing the dozen or so book clubs that meet regularly at Cresswind. One of them, a group of men, call themselves the Curmudgeons. If I were writing a Cotton Patch translation of the New Testament, I would definitely include Paul’s Epistle to the Curmudgeons.

Many thanks to Wilson and Kris Golden (seen in the photo with Pam and me) for inviting us to Cresswind for a lovely evening.

October 20, 2016

Was that profiling?

I’d like to talk about something that happened on the way home from a book talk last night -- something related to our discussion that troubled me.

I was invited to speak about “The Class of ’65” at North Springs United Methodist Church in Sandy Springs, north of Atlanta. After a fine barbecue dinner in the fellowship hall, the pastor, Sara Webb Phillips (seen here), introduced me and we talked about the book and its themes of forgiveness and reconciliation. Near the end of the session, one of the members said that her children were much less race-conscious than older generations and expressed hope that the passage of time will help heal our divisions. I nodded in agreement. Then, on the way home, my wife and I encountered something that reminded me that some attitudes are so deep-seated that it takes more than time to unravel them.

Pam and I stopped by a Kroger store to pick up some milk and were approached in the parking lot by two African-American boys, maybe 12 years old, who said they were selling peanut brittle for a school fund-raiser. We found it odd that they were doing that at 8:45 p.m., but they were polite and had a clipboard to write down orders, so we came away thinking that maybe it was all legit.

As we approached the store, two white women who looked to be college-age motioned us over and asked what those boys were doing.

"They said they were selling peanut brittle for a school project," I said.

"Well," one of them replied, "I had my car window broken the other night, and I just didn't want to deal with that again.

Pam and I glanced at each other knowingly and walked on.

I don’t blame the young women for being suspicious of someone selling candy in a parking lot after dark. I mean, we were. But to see two black kids like that and immediately think about your car having been vandalized -- some people would call that racial profiling. It’s a good example of the tribal assumptions we all make in our day-to-day lives. This is the hard part, people: facing our attitudes honestly and dealing with them.

Maybe we can discuss it at my next book talk.

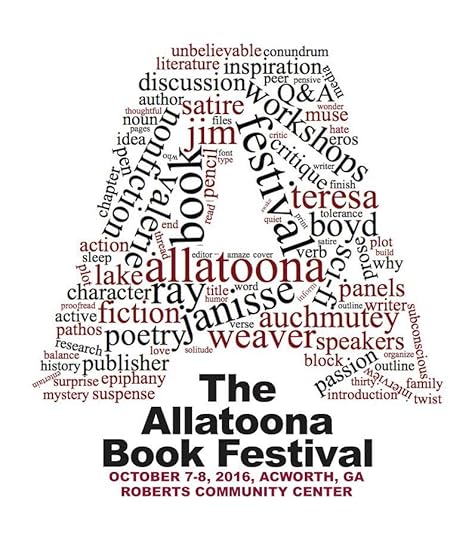

October 10, 2016

A book festival reunion

You usually run into people you know at book festivals, but the one I did this past weekend felt more like a mini-reunion.

It started when a former editor of mine invited me to speak about “The Class of ’65” at the first-ever Allatoona Book Festival in Acworth, northwest of Atlanta. Since we worked together at the AJC, Ellen Kennerly has become executive director of the Acworth Cultural Arts Center, the group that staged the event. That’s her on the right in the photo. The person on the left is another Ellen -- Ellen Ward of the FoxTale Book Shoppe in Woodstock, who was a classmate of mine at Avondale High School.

There’s more: The picture was taken by Teresa Weaver, another editor of mine, who was also on the program because of her long tenure as book critic at the AJC. She came to the festival with Valerie Boyd, another former colleague of ours, who was on a panel to share her experiences as a successful biographer of Zora Neale Hurston.

Not done yet: The speaker before me was an old friend, author Eric Haney, who came with his wife, Dianna Edwards, another former AJCer. And when I took the podium, I looked out and saw Brian O’Shea, yet another former newspaper colleague. (Rest assured, there were many people in the audience I had not worked with or gone to school with.)

It was nice to see so many familiar faces. After my presentation, we had a lively question-and-answer session about the book’s themes of forgiveness and reconciliation -- and the limits thereof -- and we talked about the state of race relations in America. All in all, it reminded me of some of the difficult but important discussions we used to have during story meetings at the newspaper.

Thanks for inviting me, Ellen, and good luck to the Allatoona Book Festival. We need more book festivals in Georgia.

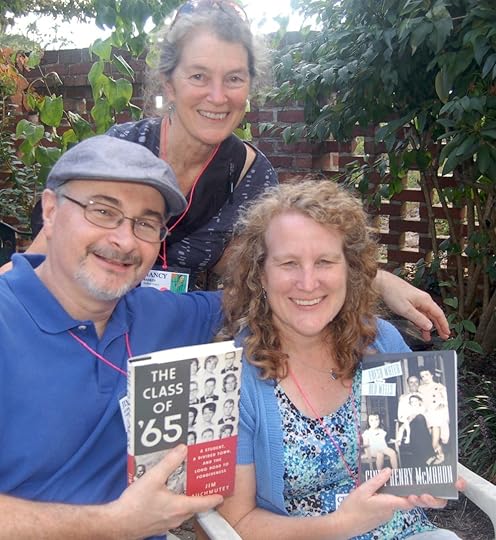

September 12, 2016

Finding forgiveness in God's country

When I was working on “The Class of ’65,” I learned about Al and Carol Henry, an outcast minister and his wife who moved to Koinonia with their family in 1965, the year Greg Wittkamper graduated from Americus High. I later heard that their youngest daughter, Cindy Henry McMahon, had completed a memoir about her family’s colorful and painful journey, “Fresh Water from Old Wells.” I had the pleasure of meeting Cindy last weekend at the Carolina Mountains Literary Festival in Burnsville, near Asheville, where we both made presentations and then did a program together. I’d like to tell you a little about her story.

Cindy was born in 1966 at Koinonia, a year after her father lost his pastorate in Birmingham because he had participated in the Selma voting rights march and other civil rights activism. The family came to Koinonia to lick its wounds and restore its spirit. Things didn’t quite work out that way. While they were living at the farm, Cindy’s father began to show signs of bipolar disorder. He became violent toward their mother and eventually abandoned the family to become something of a hobo. Carol and her daughters scraped by in Atlanta and then settled in Celo, a Quaker community in the shadow of Mount Mitchell, N.C., where they finally found peace and acceptance.

In our joint session, Cindy and I talked about the themes of forgiveness in our books: how she had to come to terms with her father, how Greg reconciled with the classmates who had shunned and harassed him in high school. Forgiveness, we agreed, does not mean forgetting or pretending that some wrong never happened. It’s something you do for you. Anger, Cindy said, paraphrasing a Buddhist proverb, is like a hot coal you clutch in your hand. It burns no one but yourself. Forgiveness is the act of putting down that stone and moving on.

I’ve done numerous talks and book festivals since “The Class of ’65” came out; this was one of the most meaningful. Thanks to Lucy Doll, Kathy Weisfeld and everyone with the Carolina Mountains Literary Festival for including me in your lovely event. Thanks to Cindy for sharing the stage and for writing such a fine memoir (available from Mercer University Press). And special thanks to her big sister Nancy Raskin (shown in the photo behind Cindy and me) for facilitating the whole thing and for taking such good care of Pam and me at the Celo Inn, which she runs with her husband, Randy. The scenery was wonderful, the conversation was lively, the coffee was good and strong -- who could ask for anything more?

July 18, 2016

Must read

The Georgia Center for the Book has chosen “The Class of ’65” as one of one of its Books All Georgians Should Read for 2016. Your not-quite-humble correspondent is honored to be included in this annual rite of recognition.

The list is compiled from nominations received by an advisory council made up of writers, educators, librarians, media members and others. More than 125 books about Georgia topics or by Georgia authors were considered for the latest roster. Among the 10 titles that made the cut: “Where We Want To Live” by Ryan Gravel, the man who conceived Atlanta’s Belt Line; “Blue Laws” by poet extraordinaire Kevin Young; “Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty” by Charles Leerhsen; and “How I Shed My Skin: Unlearning the Racist Lessons of a Southern Childhood” by Jim Grimsley. I was pleased to see Jim’s name on the news release; we shared a stage last September at the Decatur Book Festival.

There’s also a list of 10 Books All Young Georgians Should Read that includes the delightful “The Wheels on the Tuk Tuk” by Kabir Sehgal and Surishtha Sehgal.

The Georgia Center for the Book is the state affiliate of the Library of Congress’s Center for the Book. The center is hosted by the DeKalb County Public Library and sponsors lectures and other programs promoting Georgia’s literary tradition. One of those programs will be in August at the Decatur Library auditorium to present the latests lists of books all Georgians should read.

It’s free and open to the public. 7:30 p.m., Thursday, Aug. 18. Come by and join us if you can.

June 6, 2016

A special letter

I mentioned recently that my friend Jane Lamkin had sent a copy of “The Class of ’65” to the novelist Anne Tyler. Guess what? She actually read it, in one gulp.

Jane has corresponded with Tyler since the 1980s, when she first became well-known for “The Accidental Tourist” and the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Breathing Lessons.” Jane thought she would be interested because Tyler spent part of her childhood at Celo, a Quaker commune in the mountains of western North Carolina, and would probably know something about Koinonia and the persecution it experienced in Georgia.

A few days after sending the book, Jane received a thank-you letter from Baltimore. “I sat down with the book yesterday afternoon intending just to read the first chapter,” Tyler wrote, “and lo and behold, I finished it by evening; it was that riveting! Gosh, adolescence is hard enough without going through Greg Wittkamper’s ordeal. He was remarkable.”

I couldn’t agree more about Greg. Thank you, Jane, and thank you for reading, Anne Tyler.