Jeff Sayre's Blog

September 15, 2014

Joining The Band, The Apple Watch Band

Months before the Apple Watch was revealed (then speculatively referred to as the iWatch), there were rumors that the watch may have as many as ten biosensors. However, at the big reveal this past Tuesday only one biosensor, a heart-rate monitor, was mentioned.

This week new reports came out reaffirming the rumors that the Apple Watch may indeed have more sensors yet to be revealed. One exciting possibility that struck me as I was watching the live reveal video was that the wristband may be one of the secrets Apple is planning to leverage.

Based on the below images, which are screen captures from the above linked to reveal video, could Apple be scheming to place additional sensors in the wristbands?

Does this show that the Apple Watch Bands have the potential for electronic contacts?

Look at the image above. Do you see the three “contacts” on the inside surface of the removed band’s base? The center “contact” is likely part of the band’s release mechanism, but the outer two “contacts” are darkened, as if nothing is there.

Does this show that the Apple Watch Bands have the potential for electronic contacts?

Now look at the next image above showing a sports band. Do you see how the outer two “contacts” have something in those positions?

The differences in renders between the two video graphics might have a simple explanation. For instance, it may just be a minor detail that was not caught when the graphic animations were created (I assume these are graphic animations and not actual video of a real life Apple Watch). Perhaps all three of what I am calling “contacts” may be required to properly secure the band to the Apple Watch body. But it might also be that the two outer “contacts” could serve in an additional capacity — that of signal transmission.

Could these outer “contacts” allow a connection to the Apple Watch’s processors? Could they allow for signals to be sent between wristband-based sensors and the Apple Watch’s onboard computer? If so, the possibilities could be astonishing!

Why Put Tech In the Wristband?

In a Google Plus post I made two and a half months ago, I offered the following thoughts on the Apple Watch (then called the iWatch):

If the iWatch (Apple’s, Google’s, etcetera) does not utilize as much of the wristband as possible to position sensors and other components, then I will not be interested. I’m not looking for another wristwatch that has interchangeable bands that require the user to pony up more money.

That is a big waste of real estate. I gave up wearing watches more than ten years ago as the wristband annoyed me. It did nothing other than hold the device on your wrist. I decided I would not put any type of bracelet on my wrist until it maximized the benefit for the space it occupied on my skin.

If the iWatch is supposed to be a health (even medical) device, then drop the tech-free strap and add a series of sensors into the band. Let’s be fashion forward by being future forward. Wristbands without tech should be a thing of the past.

Note: Since that post, I am beginning to understand why Apple views wearable tech as a fashion accessory. Such devices that touch your skin, that hug your body, are personal objects. Having choices matter to users.

If this conjecture is true, that some Apple Watch wristbands will have embedded sensors, then I retract my above comment that “I’m not looking for another wristwatch that has interchangeable bands that require the user to pony up more money“. If Apple has innovated the Apple Watch to enable Apple Watch bands that have interchangeable tech, that have additional sensors, then it could very well be of great interest to me and many others.

A Few of My Previous Apple Watch Posts on Google Plus

I’m Not Sure What To Think Of Smart Watches In General

More iWatch Speculation. Only “Time” Will Tell…

Some Outside Resources

March 13, 2014

The Superorganism, Superorganization, and The Global Brain

I finally had time this morning to read Gideon Rosenblatt’s latest thought piece, Are Organizations Alive? A Different Take on the Evolution of Technology on his The Vital Edge blog.

It is another wonderful piece and an excellent read. It is not long, so please read it before continuing with my post.

So as not to thread jack his post announcing his article, I’ve written this post as my ideas might be considered tangential to his concept. But I believe they are actually a different way to approach the same issue.

It’s Alive!

Science (biology specifically) has very salient definitions of what determines if an entity is a life form, of what it means to be alive. From a purely scientific definition, an organization, an entity that is basically an artificial construct defined and made possible by laws created by humans, will never be considered a living object.

This basic definition of life, one that is at the center and foundation of modern biology, cannot offer support for Gideon’s premise. However, by moving up one level of system abstraction to the field of ecology, there are theories and observations that can be used to realign his basic premise offering solid support for his idea.

Nested CASs

Organizations are artificial systems that leverage collective intelligence to accomplish a specific set of goals. As organizations deploy technology into and integrate technology from the Internet’s rising mesh network, these seemingly disparate conglomerates of collective intelligence (collectives) will become a self-assembling and self-organized connective made possible by the AI systems within the evolving global mesh network itself. In other words, collective intelligence will be augmented and transformed by connective intelligence. Collective intelligence will eventually merge with connective intelligence.

What does this mean?

Each organization can be viewed as a single complex adaptive system (CAS). The theory of complexity has been studied in many fields with ecology perhaps offering the most salient examples. I wrote a post on this issue a few years back. If you want to learn more about complexity, I encourage you to read my piece, The Ecosphere And the Economy.

Via the revolutionary and evolutionary advantages offered to organizations that plug into the Connective, the single complex adaptive systems that neatly define (and compartmentalize) each organization will transform into a human-machine augmented nested complex adaptive system. This is where Gideon’s premise takes flight, in my opinion.

The Superorganism

In biology and ecology a superorganism is a collection of the same or similar organisms that are connected in a functional unit all working to accomplish the same set of goals. Whereas I’ve purposefully distilled the concept down to this simple definition, it is sufficient to elucidate the bigger picture.

Gideon’s idea deals with organizations, and not organisms. I propose that we adopt the meaning and concept of ecological superorganism and apply it to the organizational connective discussed above. I propose that we call this the Superorganization.

At its foundation, the Superorganization can be considered a natural outgrowth of the ecosphere. It is a manifestation of the collective energies and connective intelligence of the currently dominant life forms on Earth (okay, perhaps microorganisms deserve that title). As such, the Superorganization will become an integral part of our life support system. It may not be alive in a classical scientific definition, but it is alive via some of the subsystems that build, protect, and grow it.

The Superorganization is an artificial construct made possible by the larger superorganism that is Earth (see, Gaia theory).

Moving Beyond The Superorganization — The Global Brain

The organizational connective, the Superorganization, will be an artificial nested complex adaptive system (i.e., created by humans and machines). It will help support, transform, nurture, and even challenge (not necessarily in positive ways) the living (biological based) systems of our ecosphere (Gaia).

Once the Superorganization blinks into existence, parts of humanity will merge with it, becoming co-dependent on this higher-level organizational connective. I talk about this concept in my piece, The Emerging Global Brain and the Internet’s Future.

Learn More

If you are interested in learning more about the ecological and sociological concept of superorganism, you cannot do any better than reading E. O. Wilson’s and Bert Hölldobler’s seminal work on this topic, The Superorganism: The Beauty, Elegance, and Strangeness of Insect Societies.

Also here are a few of my thought pieces on the future of humanity that fit within the interest graph of this topic:

The HyperWeb: it’s All About Connections

Cybernetics, the Social Web, and the (Coming?) Singularity

February 28, 2014

Are You “Ment” To Be A Great Leader?

What makes a great leader? Is it solid management acumen? Is it an aggressive drive? Is it the desire to win?

What makes a great leader? Is it solid management acumen? Is it an aggressive drive? Is it the desire to win?

The sign of a great leader is often more nuanced than a set of applied, outwardly facing skills or a shared attitude. Not even impressive accolades and sterling credentials are signs of a great, or even good, leader.

Great leaders are evident by the subtle ways in which they interact with a company’s three human asset groups — employees, clients, and the public. Great leaders strip away the preconceived notions of management when engaging with these human asset groups.

How do they do this? By focusing solely on the “-ment” in management. Great leaders remove the blinders of discrimination. They strip the gender (the “man” in management) and age (the “age” in management) out of the equation.

Instead of biasing, or even thinking about, a person’s worth by considering their gender or age, they try to determine how to interact and communicate with a person based on the below “-ments”.

The Three “Ment” Categories Of Great Leaders

Great leaders utilize these “-ments” to assess others:

achievement

agreement

alignment

commitment

engagement

improvement

involvement

Great leaders leverage these “-ments” to make others successful:

acknowledgement

advancement

assessment

compliment

development

encouragement

enjoyment

enlightenment

equipment

excitement

experiment

fulfillment

investment

nourishment

readjustment

realignment

reinforcement

Great leaders do not practice, or are slow to apply, these “-ments”:

argument

bewilderment

commandment

debasement

denouncement

detachment

diminishment

disagreement

disappointment

discouragement

displacement

embarrassment

entitlement

entrapment

harassment

judgement

micromanagement

misstatement

mistreatment

nonengagement

noninvolvement

outplacement

punishment

resentment

underinvestment

underpayment

Great leaders focus on what others need and what others, and themselves, lack. They learn by listening to those around them. They do not judge until they have all the facts, and then they judge in a way that is not accusatory, condescending, or unproductive. Great leaders are focused on helping others win and in that process they win too.

If you wish to be a great leader, ignore the outward facade of people — their age, their gender, their sexual preference, their size, their style. Ignore all the obvious characteristics with which people are labeled, grouped, and judged. Focus, develop, and nurture the inward attributes of people and in doing so you will help them and you to both succeed.

Great leaders practice “-ment”!

March 11, 2013

Google Plus Communities: Analyzing The Impact On User Engagement

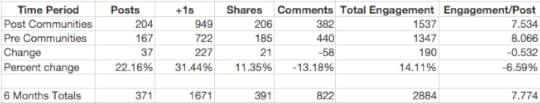

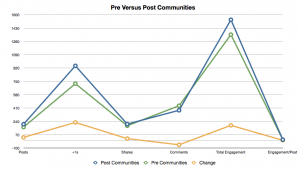

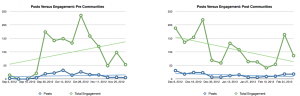

Google Plus Engagement Pre Versus Post Communities; clicky to embiggen

I’ve suspected for awhile that since the launch of Google Plus Communities three months ago, I am not receiving the same level of engagement as I did in the past. My analysis does confirm my suspicions. I now have to work harder to receive the same overall level of engagement as in the past. More over, the quality of that engagement is declining.Whereas these results reflect my experience, they might not necessarily be applicable to all users and may not be as meaningful when applied across the entire Google Plus ecosystem. There are some power users, or more accurately G+ attractors — people who attract massive followings — for whom the quantity and quality of engagement is most likely constant or even increasing. However I do believe that for the majority of Google Plus users, these results most likely apply.

Want the synopsis? For a tl;dr version click here, but you’ll miss all the cool charts!

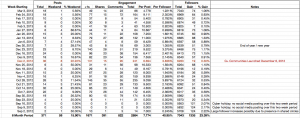

Basic Methodology

I assessed engagement with my content over the most recent six month period. I choose a six-month period of time for a reason. Google Plus Communities launched on Thursday, December 6, 2012. It has been three months since the launch — actually, thirteen weeks have passed. I gathered data for the 13 weeks prior to the launch of Communities and the 13 weeks after. The week Google Plus Communities launched was used as the dividing point and did not go entirely into one content bucket or the other (more on that below). Thus I gathered data over a 27 week period.

All data comes from personal Stream and Community Stream posts that I initiated. As I rarely post to a limited audience, all data comes from public posts. In fact, since I first started using Google plus, I’m guessing that Ninety-eight percent (or more) of my posts are to the public. That aspect of my posting behavior remains unchanged.

For a given post, engagement was calculated by tallying all the +1s, Shares, and Comments for each post. Plus Ones were only counted for the OP and not for any received on comments I made within my own posts. Also, I excluded any comments I made to the comment stream of my own posts and any shares I initiated of my own posts as I wanted to get an accurate assessment of engagement with me, with my content. My engagement with my own content did not count.

Each comment (excluding my own) was counted as a single point of engagement. On numerous occasions the same person would add more than one comment to a post’s comment stream. Each comment was counted as one point. In other words, I did not count unique users commenting. I counted each piece of engagement.

The total engagement for a given week is simply the summation of all engagement across three categories (+1s, Shares, and Comments) for all posts in a given week. I then calculated engagement per post per week by dividing total engagement for that week by the number of posts for that week.

The engagement per follower ratio is not an actual calculation of engagement activity per follower. It is a coarser metric to see how total weekly engagement with my posts has varied as my follower count has changed over time.

Follower numbers by week come from CircleCount. Here is the link to my CircleCount data.

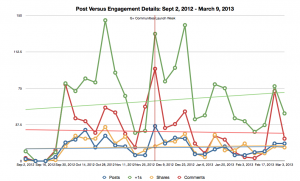

Raw Engagement Data; clicky to embiggen

Each regularly active Google Plus user understands engagement activity differs on weekends versus weekdays. For most of us, engagement is lower on weekends than weekdays, often with a noticeable decrease in engagement starting Friday afternoons. Therefore, I tallied posts made on the weekend in a separate column. So, as an example, the week that just ended — the week of March 3 — I made a total of 18 posts across all seven days. Out of all the posts made for that week, one was made on a weekend and the other seventeen were posted during the work week (Monday through Friday). I captured these data to see if there was a significant difference between my weekend-posting patterns pre Communities versus post Communities and, if so, whether or not there might be some correlation with impact on engagement.

Finally, engagement across the three categories is not weighted. Each point of engagement is given an equal weight. Even weighted, the percentage change between pre and post Communities would be unaffected.

All engagement is not equal. A Plus One is the lowest quality of engagement. It is analogous to a Facebook Like and is a quick and simple way for someone to acknowledge your post (or comment). A Share is of higher quality as it sends your thoughts into the Streams of those who follow the user that shared your post. A share also may result in new users following and possibly engaging with you. But, in most cases, shares fracture your post and result in engagement and conversations occurring outside of your original piece of content. A comment is the highest quality of engagement as it starts or adds to a conversation about the content of your post and is contained entirely within your post. When reading the below analysis, keep in mind that there is a qualitative difference in quality of engagement with type.

A note about the charts. The trend lines on each chart are software calculated. In other words, I did not eyeball draw them.

Results and Analysis

Overall engagement with my posts (threads, OPs) has increased by 14.1 percent since Google Plus Communities launched but the clear trend is decreasing engagement over time since the launch. Communities appear to be cannibalizing user attention from personal posts and the type of engagement has shifted from higher quality to lower quality.

Over the recent six-month period, my follower count has increased by 23.4 percent. Whereas that is a nice gain, the metrics show a mixed picture. Total engagement has increased 14.1 percent but the figure for engagement per post has actually deceased 6.6 percent.

All things being equal, with more followers — more people who actively choose to follow you — you would expect an increase in overall engagement, or at least for engagement to have remained consistent over this period of time. Yet the quality of engagement is not keeping up with my gains in follower count.

Pre Versus Post Communities: The Trend Is Not Your Friend

To assess what might be going on, I divided this six-month period (27 weeks actually) into two buckets — a 13 week pre-Communities bucket and a 13 week post-Communities bucket. The week in between these two buckets, the week of December 2, 2012, is the week that Google Plus Communities launched. I split that week up as well, placing the data from the first four days of the week in the pre-launch Communities bucket and the last three days of the week in the post-launch Communities bucket.

Pre Versus Post Communities’ Data

Google Plus Engagement Pre Versus Post Communities; clicky to embiggen

In the sections below, you will see that I created charts for the entire six-month period, adding a trend line to each chart. I also created two additional charts that broke down engagement into pre- and post-Communities — the two different buckets I described in the above paragraph. Looking at the six-month chart gives you one picture. But looking at the pre- versus post-Communities charts reveals something else.

In the sections below, you will first see the six-month chart with a brief assessment. Then you will see the pre- and post-Communities charts.

Quantity Versus Quality

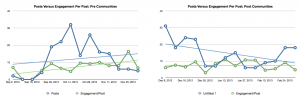

The quality of engagement has changed. Post Communities I’ve seen a respectable 31.4 percent increase in +1s to my posts and a healthy 11.4 percent increase in Shares of my posts. However, I have also experienced a 13.2 percent decrease in Comments to my OPs. Taking all together, this results in a modest gain of 14.1 percent in total engagement.

That does seems like a net positive. But remember that Comments are the highest quality of engagement and Plus Ones are the lowest. Even though I have more overall engagement, the lion’s share is coming from a large percentage increase in Plus Ones. The quantity of engagement has increased but the quality has also decreased.

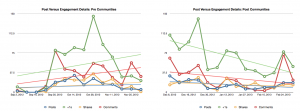

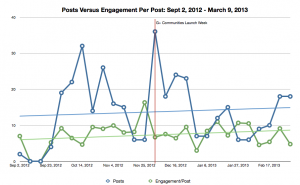

Clicky to embiggen

When I looked at Posts versus Engagement breakdown of the data for pre and post Communities, the nicely inclined trend line in Plus Ones that is seen over the six-month period is revealed to be anomalous. The trends for engagement metrics (+1s, Shares, and Comments) since the launch of Google Plus Communities are actually on a decline. You will also notice that the trend line for my posting activity is also on a decline.

Pre- Versus Post-Communities Engagement Details; clicky to embiggen

With regards to posting frequency, pre Communities, I averaged 12.8 posts per week. Post Communities, my average number of posts per week increased to 15.7. But as the charts reveal, my weekly posting averages are now on the decline as well. I talk about why I’ve decreased my posting frequency in the conclusion section below.

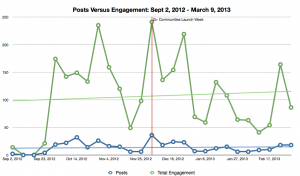

Here are the charts combining all weekly engagement. The six-month chart does show an increasing trend in total engagement whereas posting frequency remains relatively steady and level.

Clicky to embiggen

However, the pre- and post-Communities’ charts show a different picture. There has been a downward trend, a steady erosion in total engagement since Google Plus Communities launched three months ago.

Pre- Versus Post-Communities: Posts Versus Engagement; clicky to embiggen

When engagement per post per week is considered, it is clear that overall engagement is actually slightly lower than before. Prior to Communities, my engagement per post average was 8.1 precent. But since the launch of Communities, my engagement per post average has declined by 6.6 percent to 7.5.

Click to embiggen

Pre- versus Post-Communities: Posts Versus Engagement Per Post; clicky to embiggen

As most Google Plus users know, engagement on the weekends tends to be noticeably lower than with weekday postings. I looked at any impacts that weekend versus weekday posting might be having on the results. Prior to Communities, 19.8 percent of my posts we placed on weekends. After Communities, my weekend posting average declined to 12.8 percent of all posts. As a greater percentage of my posts were made during the weekdays after the launch of Communities, I would have expected to see more overall engagement per post. But that was not the case as detailed above.

What does this all mean? Whereas total engagement has increased, and my follower count has ballooned, the average engagement per post is decreasing and the quality of that engagement has changed. I am having to work harder — post more often than in the past — to draw people’s attention and the quality of the interactions are of lessor value than before.

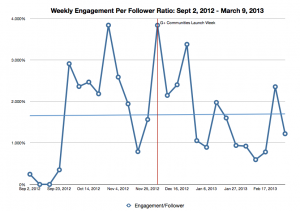

Engagement Per Follower

Another ratio I looked at was engagement per follower. This is a coarser metric to see how total weekly engagement with my posts has varied as my follower count has changed over time.

In theory, as you gain more followers you would expect engagement to increase. Indeed, as discussed above, with a follower increase of almost 25 percent over the most recent six-month period, I have experienced an overall engagement increase of 14.1 percent.

As the chart below shows, over the six-month period in question, there does not appear to be any apparent change in weekly engagement per follower ratio. The trend line is ever so slightly upward slanting, but for the most part it is level.

Clicky to embiggen

However, when I looked at the pre versus post Communities weekly engagement per follower ratio, a different picture emerges. The trend before and after Communities is very evident. Before Communities launched, the trend was an increase in my weekly engagement per follower ratio. But over the past three months, since the launch of Communities, the trend has reversed with an obvious steady decline in my weekly engagement per follower ratio. I am gaining more followers but it is not resulting in a corresponding increase in engagement.

Clicky to embiggen

One, of several, explanations for this observed trend is that my follower base is actually becoming less active over time. So, whereas I have more overall followers, the percentage of those followers who are (still) active is decreasing. This may point to a more systemic issue with Google Plus — inactive followers. Could the decrease in engagement quality and the fracturing of personal brands be driving once frequent, active users away from Google Plus?

Conclusion

(tl;dr)

After three months of Google Plus Communities, there is sufficient data and user experience to properly analyze what impact Communities may be having on user engagement. The engagement data from my Stream clearly demonstrates that Communities are impacting engagement — and most of it is not positive. Although I do think there is value in the Community model, through fracturing our Streams, Communities are diluting personal brands.

Competition for user attention has increased as user Streams have fractured and become more saturated with content from individuals and Communities. It is easier to give a quick +1 or an easy Share than it is to take some time and leave a comment, to engage in a conversation. The unveiling of Communities has changed the nature of engagement in Google Plus.

My data indicates an increase in overall engagement rates since Communities launched in early December. However the specific data clearly shows that there has been a reduction in the quality of user engagement. Whereas Plus Ones have gone up by 31.4 precent, Comments have decreased by 13.2 precent. But any gains in overall engagement may have been fleeting as the trend line indicates a decline in all engagement metrics since the launch of Communities.

Furthermore, Plus Ones are not the same as engaging in conversation by leaving a comment. A comment is a much higher level of engagement. It is a higher quality type of engagement. Receiving more Plus Ones is not the same thing as spawning more conversation. Google Plus was once referred to as a conversation ecosystem. Has that time come and gone?

A result, I’m having to work harder to attract user engagement, posting more posts on average per week while at the same time seeing a decline in the overall engagement per post metric. Even though my follower count has increased by almost 25 precent over the past six months, and my average post count per week is higher than before Communities launched, the engagement I receive per post has declined by almost seven percent.

Now it might be that I’m simply sending more noise into others’ Streams than before Communities launched. In other words, it might have nothing to do with Communities. However, I’m pretty sure that my signal to noise ratio is roughy the same. It could also be that the quality of users that are now following me is not as high as in the past. Perhaps the interest levels and engagement coefficient (whatever the heck that means) of the overall pool of Google Plus users is being reduced, diluted as more people join. This could explain why my posts’ engagement levels have declined even though my follower count has noticeably increased.

Whereas these other factors could be partially in play, I’m guessing that the social dynamics of Google Plus have been shifted by Communities. I know that I’m having a difficult time keeping up with all the content flowing into my Stream — much of the new flow the result of posts from the couple dozen of Communities I’m a member. Also, I too am guilty of providing lower quality engagement as I find it easier to give a quick +1 than to leave a comment.

My analysis does show that since the launch of Google Plus Communities, I have averaged more posts per week than prior to its launch. However, it also shows (via the trend line) that my posting frequency is now declining.

Perhaps the trend of my declining posting frequency is the result of my intuition, the realization that the investment I’ve been putting into Google Plus is not accruing the same benefits as in the past. Investing time into Google Plus is simply not as rewarding as before.

It is clear that, at least for my personal brand, the launch of Google Plus Communities has changed the nature of interaction, of engagement. Google Plus now is less about the personal brand and more about homogenizing our individuality into Community Streams. Whereas I believe Communities offer some value, it is too bad that the ad hoc conversation ecosystem that used to exist before its launch has become attenuated.

As a result of what I’ve described above, I have lost touch with a number of people with whom I used to engage a consistent and regular basis. Many of these people have diverted a significant portion of their Google Plus time into Communities — or so I assume. That is an issue because it is harder to follow a given person’s posts in a Community — their posts get diluted by all the other members of the Community and soon get sent below.

The reason I follow people is so that their ideas will flow into my Stream. But with Communities, you get the ideas of everyone, not just the people who you personally selected. I cannot spend the time clicking on users’ profiles just to keep caught up on their activities and thoughts across the Google Plus ecosystem. That is inefficient.

What action do I need to take to address this change in engagement quality and quantity? What can be done to shift the trends? How can I reconnect with those users that used to be a big part of my Google Plus experience?

Post Conclusion

It would be interesting to look at these same metrics for other Google Plus users and see whether my results bear out for them as well. If you are interested in performing your own analysis, you’ll have to gather the data on your own. It is an easy, straight forward process, but it does take time. You might be able to cut some code using the Google Plus API to pull these figures automatically for you. I decided not to do that as this was a one time effort and I do not plan to continue tracking these metrics.

What are your pre versus post Google Plus Communities’ experiences? Have you noticed a change in engagement levels (both quantity and quality) since the new Community model was launched? Has the change been positive, neutral, or negative?

Epilogue

During the first full week of the Google Plus Community role out, I wrote four posts on the topic of what Communities might mean for personal brand and user Stream management. You can find those posts here:

My Individuality Atoms Are Derezzing

Duplicating Old Posts Into New Communities

Google Plus, G+ Communities, And Your Stream

Google Communities And Personal Brand Dilution?

Based on the analysis of the data presented here, I still believe that the best way for Google to integrate the Interest Graph into Google Plus is by enabling user-based Content Channels. I’ve written several posts on that topic before. Here is an excerpt of one of my comments in the comment stream of my post, Google Communities And Personal Brand Dilution? (See above link)

Whereas G+ Communities are helping to create the Interest Graph within G+, the way they are currently implemented means that your interests do not necessarily get connected to your personal brand in a way that is easy for your followers to see.

Whereas all of your public posts and posts within public Communities do seem to appear on your personal profile page, I think it is too much to ask or expect your followers to click through to your profile just to make sure they did not miss anything of interest to them. Your followers deserve the right to stay within their Stream, to discover your content in the container that they spend the most time.

I still want the facility to follow people’s interests via Content Channels. I want to subscribe to your posts about your interests and not have to follow you into various Communities just so that I might get to see what your thoughts may be about a certain topic (interest).

January 15, 2013

The Death of Ecommerce Startups?

Imagine having to collect and remit sales tax to hundreds of taxing authorities. For etailers, that nightmare may soon be a reality.

I’m working on several startups concurrently. One which will hard launch later this year is in the epublishing space. The second one is in the biotech space. This startup is in its nascent stages as my partner and I are still building out the founding team and working on the business model. The third, and newest concept, is an ecommerce startup in the health and fitness space.The last mentioned opportunity is actually not a startup yet as I am in the information-gathering stage. Whether I decide to promote it to a viable startup depends on the results of what I call my startup due diligence process.

Red Flags A Waving

As I’m going about the process of due diligence with this concept — determining whether or not this opportunity makes business sense — a big potential red flag has become apparent. This year or next, there might very well be a massive headache with respect to collecting online sales tax from out-of-state customers.

Since the inception of ecommerce on the Web, online sales have been exempt from state sales tax — with the exception of the state(s) in which you have had a physical presence. It is believed that this respite from the burden of having to comply with the varying taxing laws of hundreds (thousands) of different taxing authorities helped skyrocket the success of the Web as a business platform.

But if various state governors get their way and manage to persuade the US Congress to implement an out-of-state sales tax, it could be curtains for online retailing — at least the startups and small to medium sized etailers. Why?

If some form of this legislation gets signed into law, online ecommerce sites would be required to determine the proper sales tax owed by each customer based on the geographic location in which they reside and then collect and remit taxes to each of those taxing jurisdictions. Since there are literally thousands of different taxing authorities in the United States, that would be a hellish burden. Remember, this is compared to an in-state, Brick-and-mortar retailer who collects at just one state and one local sales tax rate.

Benefits Derived Versus Payment For Nothing

In theory, both online and brick-and-mortar businesses receive some benefit from state and local government services and programs. However, that is only if they are physically located in the jurisdictions of those governmental entities. What kind of relevant, realistic benefits and services would an online business receive from the hundreds or thousands of out-of-state taxing authorities to whom they may soon be forced to remit sales tax payments?

Let’s look at this from the standpoint of a brick-and-mortar store (B&M) being required to charge a sales tax based on the state and county of each of their customers. Although most customers of B&Ms are likely in-state, local citizens, many B&Ms have customers from different counties within the state, and different states. What if these B&M retailers had to ask each customer their home address and then make sure they charged the proper state and local sales taxes for that customer? They would then have to remit the sales tax to each state and local authority.

How many small mom and pop shops would be able to comply with that requirement? How many people would decide not to open up a new business, or expand into a new physical location in another state, if they were under the same onerous taxing rules?

Legally-legislated Enforcement Money?

Requiring online etailers to monitor, collect, and remit out-of-state sales tax is tantamount to the days of gangs and mobs charging local shop owners enforcement money. If the shops kept paying the money, the mobs would not hurt the owners nor shut down their businesses. Other than those benefits, they did not truly derive any useful services in return for monies paid.

Yet that is exactly what this legislation will amount to for tens of thousands of small- to medium-sized etailers. They will be forced to collect and remit payments with no benefits received in return — other than the promise of not being fined, sued, or shutdown.

The threat of a nightmarish onslaught of paper work may very well make me decide not to pursue this startup concept. The regulatory overburden might cause other ecommerce startups to fail, or not even get out of the starting blocks. It could be the end of ecommerce startups.

How Likely Is This Threat?

There is proposed legislation in the US Congress by Senator Mike Enzi (R-WY) that would reverse the legal precedent set by the Supreme Court that exempts online and catalog businesses from having to collect out-of-state sales tax. According to this resource, in past rulings that dealt with the issue of out-of-state collection of sales tax, the Supreme Court has basically stated that:

…the interstate commerce clause of the Constitution bars a state from compelling an out-of-state retailer from collecting taxes on sales to its residents…that collection is a burden on interstate commerce…[and] that taxes must be fair and nondiscriminatory, that there must be substantial nexus with the jurisdiction and a relationship between the tax and any state-provided services.

Requiring out-of-state businesses to manage the collection and remittance of in-state sales tax would cause an undue burden on the etailer — a burden that would not come with any viable, tangible, or reciprocal benefits.

If passed, this law would make etailers cringe each time they obtained a new customer that came from a state or locale to which they had previously not sold anything. With each new geographic location served, additional paperwork, sales tax remittance checks mailed, and compliance monitoring would be required.

In an attempt to provide a simplified method for collecting sales tax, some legislators have proposed what they call a Streamlined Sales Tax Agreement (SSTA). Would this make it easier for out-of-state retailers to comply with this new law? Not really.

Also from the above linked-to resource:

To start with, mandatory tax collection under the SSTA would cause thousands of merchants throughout the United States to be confronted with the entirely new obligation of collecting tax for over 7,500 local tax jurisdictions (including school districts, transportation districts, sanitation districts, sports arena districts, etc.) This will create an enormous increase in the complexity of doing business for interstate marketers –certainly not a move towards simplification.

To make matters worse, the drafters of the SSTA failed in their original mission to reduce the number of tax jurisdictions. Under the terms of the SSTA, the number of tax rates could actually increase to over 15,000 (each tax jurisdiction is permitted to have two rates).

Even with the proposed Streamlined Sales Tax Agreement, etailers would have a massive tangle of red tape and paperwork to figure out and stay up to date on. It would essentially be an overly costly, impossible task.

To Etail Or Not Etail?

As I was going through my startup due diligence checklist, the issue of taxes came up. After a little research, I learned that the promise land of the etailing space might soon be corralled by the myopic acts of local, state, and federal legislators.

If you are concerned about the very-real possibility of this narrow-minded legislation, please contact your local, state, and federal officials and express your support for a fair across-the-board sales tax policy for all retailers. If etailers have to collect out-of-state sales tax from their customers, then so should brick-and-mortar retailers.

Better yet, let’s keep innovation on the InterWebs alive and well by siding with the Supreme Court on this issue. Taxes should only be collected and remitted in return for direct, tangible benefits from local and state government.

Other Resources

Tax Break Nears End for Online Shoppers

What You Should Know About Potential Federal Tax Law Changes

What You Need to Know About Online Sales Tax

Thanks to this resource for the copyright and royalty free piggy bank image used as the foundation of the above graphic.

October 23, 2012

Coders Of The Future Will Not Be Engineers

When most people who read my blog see the word engineer they immediately think of those who write code for a living. In other words, computer programmers who may or may not have actual degrees in computer engineering. This is the definition of engineer that you should be thinking of in the title to this post.

When most people who read my blog see the word engineer they immediately think of those who write code for a living. In other words, computer programmers who may or may not have actual degrees in computer engineering. This is the definition of engineer that you should be thinking of in the title to this post.

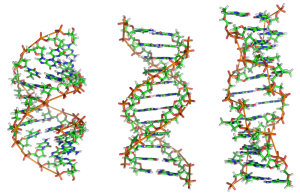

Two-years ago this Saturday, Peter Thiel made a still-controversial announcement that kids are better off dropping out of college — or not going in the first place — and instead starting a company. To help motivate his quarry, and entice (grab) young talent twenty-years old and younger, Thiel offers a two-year mentorship and $100k. However, the thumbing of a college education may be a short-lived trend. Why? Because the next version of hacker will not be the computer whiz kid who is touted as the up and coming coding guru.* The next celebrated hackers will not be able to safely learn how to cut complex code in their bedroom.

If you have kids, siblings, nephews or nieces that are ten-years old or younger, you should advise them not only to go to college, but also consider biology, chemistry, biochemistry, or molecular engineering as their major. Why? Because in as few as ten years from now, the need for and desirability of computer coding skills will plateau and the frenetic pace of new InterWeb startups will be past peak.

In fact, experienced, high-quality coders will be a dime a dozen as the wild-west decades of the InterWeb come to an end. After about 30 years of growth, dominance, and innovation, the InterWeb as the hotbed of revolutionary innovation will come to pass. Instead, biology will experience a Cambrian explosion of revolutionary innovation, a renaissance period. More precisely, synthetic biologist will be like the much-hailed hackers of today.

Biologists who code with genes will be the new cool kids on the block. Web-2.0 startups will be a thing of the past. Whereas there will be some innovation in the Web-3.0 and Web-4.0 space, the true revolutions will be occurring in the hard sciences.

Startup successes will shift from coding in binary to coding in quaternary — the base-4 system of the genes. Other revolutions will occur in the nanotech space, coding products from the atom up using the periodic table of elements as ingredients.

Hacking will not mean coding in binary on a computer to create a new app, Web-2.0 service, or SaaS product. Instead, biohacking will be the hot pursuit. This I call CaaS — Cells as a service. Cells will be our manufaturing plants. Cells will be our computers. Cells will be our platform on which we innovate. CaaS will be the new open source mantra.

DNA may be the oldest operating system (OS) on Earth, but it is also one of the most powerful OSs. We now have the tools and technology to cheaply manipulate genes, to create synthetic genomes, and to store those genomes digitally. This means that genetic innovations — for instance new medicines, new products — can be electronically shared across the InterWebs and then printed out and enabled elsewhere with ease.

Of course, in the near term, molecular assemblers will be biologically based, they will be living cells. Novel, synthetic products will be created by encoding genes to produce the molecules of which nanotechnologists dream.

So if your are thinking about a future as a coder, a current-day hacker, a computer engineer, you might want to consider biohacking instead. And please, if you are in high school and considering not going to college because you believe all the real action, innovation, and opportunities lie in cutting code at a startup, think again. The code cutters of the near future will be slicing genes, not spitting out binary.

*Note: Thiel’s 20 Under 20 Fellowship is targeted at many different areas, not just InterWeb startups. However, very few (if any) teens will be truly able to compete with university-trained nanotechnologist, biochemsits, or molecular engineers.

Image Source: Visualizations of A-, B-, and Z- DNA strands via Wikipedia user Zephyris. Image is licensed under GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 and Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

October 12, 2012

Software With Freedoms, Not Free Software

I’ve been an open source advocate, devotee, user, and developer for many years. I’m a member of the Free Software Foundation (FSF). I frequently write about the Open Web, Social Web, and Open Source of all types (software, hardware, science, data, Web standards).

I’ve been an open source advocate, devotee, user, and developer for many years. I’m a member of the Free Software Foundation (FSF). I frequently write about the Open Web, Social Web, and Open Source of all types (software, hardware, science, data, Web standards).

Much of my recent work has been licensed under the GPL. The GPL is administered and promulgated by the FSF. Apparently what is now considered the open source movement, actually was the result of a schism from the free software movement. In other words, open source was spawned out of the free software movement, not the other way around.

To some, there are philosophical differences between the two movements. They can best be summed up as follows: all free software is open source but not all open source software is free (although much of it is). You can learn more about the subtleties of this argument in this article on the GNU website, Why Open Source misses the point of Free Software.

Not Free As In Cost

This brings me to the point of this post. The usage of the word free has caused and continues to cause confusion — so much so that the article linked-to above spends time defining what is meant be the word. There are additional places on GNU’s website that take time to explain what is meant by the word free. In fact, there is even an entire article devoted to defining the phrase “free software” and the word “free” (see, What is free software?).

When you have to spend paragraphs, yet alone entire articles, defining and explaining two simple words in a two-word phrase, something is wrong.

The various paragraphs and articles on this topic on GNU’s website use catchy phrases to better define the “free software” phrase.

think of “free speech,” not “free beer”

“free software” is a matter of liberty, not price

Why is this such a big deal?

To the passerby, to the casual user, the word free has an obvious connotation — free as in zero cost. But this is absolutely wrong. It is not what is meant by the phrase “free software” and is exactly why there’s a problem. The GNU website once again has another article to help dispel the assumption that free software is free as in zero cost (see, Selling Free Software).

This issue has caused numerous headaches for me and other developers of FOSS (Free and Open Source Software ) projects. For instance, there are many WordPress, BuddyPress, and Drupal users who wrongfully assume that plugins are mandated by the GPL to be free as in cost. When this incorrect assumption is corrected — by pointing them to the Selling Free Software article on GNU’s website — they then take the stance that open source software should not cost anything. After all, they can download WordPress or Drupal for zero cost. So why shouldn’t all plugins or modules be free as in cost?

Of course, these same people often have no qualms with purchasing a premium theme from a design shop. They fail to see the irony in expecting developers to code and support their work for free, but smiling at designers who create high-quality themes and charge for them.

To be fair, there have been developers who have sold their work for years. In fact, there are more starting to do so each day. However, the concept of free as in zero cost is a direct result of using the phrase “free software”. It has caused and continues to cause issue for those of use who wish to make a living creating high-quality software with freedoms.

I wrote about the “free software” conundrum from a developer’s perspective in an article two-years ago (see, How Can BuddyPress Developers Earn a Living?). Reading the comments sheds more light on this issue.

It’s Software With Freedoms

In essence, free software is software with freedoms. Saying that would be straight forward and lead to a lot less confusion. Time could then be spent on defining and discussing those freedoms without any need to bother defining the ambiguity of a word like free.

It seems to me that the phrase “free software” is more of a marketing slogan or buzzword. Whereas “free software” does roll off of the tongue, and it does sound more tasty, the fact that it requires so much time and effort to effectively define is a problem.

I propose all FOSS / FLOSS advocates start using the phrase “software with freedoms” instead of “free software”. That way time can be spent on discussing those freedoms and not correcting the mistaken assumptions of cost. As an additional benefit, I imagine that the phrase “software with freedoms” would translate very well into a majority of languages keeping its contextual semantics intact — that is for languages that have a word for software.

About The Free Beer Logo

The Free Beer logo is an inside joke based on the issues discussed above but has transformed into a movement of its own . You can learn more about it here, The Geekiest Beer on Earth, and here, Free Beer! You can also get your own zero-cost copy of the Free Beer logo to use on your own craft brews by visiting the Free Beer project.

September 26, 2012

Kaufman Field Guide to Nature of the Midwest

Most of you know me as someone who thinks and writes about, and works and lives in, the Social Web and Future Space. Some of you have noticed my mysterious absence from the various social channels I used to participate in on a daily basis. In fact, since posting my last article on my blog more than four months ago, I seem to have derezzed from the metaverse.

Most of you know me as someone who thinks and writes about, and works and lives in, the Social Web and Future Space. Some of you have noticed my mysterious absence from the various social channels I used to participate in on a daily basis. In fact, since posting my last article on my blog more than four months ago, I seem to have derezzed from the metaverse.

I my previous two blog articles I shared with you another side of me — that of naturalist and ecologist. What I did not share at the time was that I was embarking on a new short-term project. This post describes that project in detail.

I’m Co-authoring a Field Guide!

What is this secret project I have embarked upon? I’m co-authoring a field guide with the respected, and respectable, naturalist Kenn Kaufman. For those of you who do not know of Kenn, here is a brief biography of his life and work.

My wife April and I have had the privilege of knowing Kenn Kaufman for almost 18 years since we first met him at a birding and nature conference in Sierra Vista, Arizona in 1995. Besides a lifelong intrigue with the natural world, I quickly found out that I shared another commonality with Kenn — we were both originally from South Bend, Indiana.

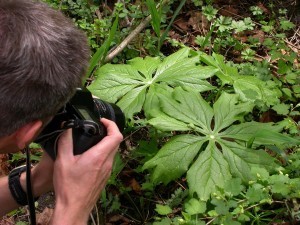

Jeff (right) spending some field time with Kenn Kaufman

This past spring, during festival — an annual celebration of bird migration and nature — Kenn approached me with a proposal. He was interested in having me as his co-author on the next book in his acclaimed Kaufman Field Guide Series. My primary responsibilities would be the botanical sections of the book.

As this would be a big responsibility and would require a big time commitment on my part, I spent five days seriously weighing the pros and cons of Kenn’s offer. As much as I needed to remain focused on my InterWeb startup, this project was captivatingly enticing.

In the end, the decision was clear. This was an opportunity I could not decline. With my years of experience as a restoration ecologist, my time at JFNew running their native plant nursery, my love of botany, and my hands-on time caring for and studying the more than 400 species of native plants that we had planted on our acre-and-a-half piece of land, this project was a perfect fit.

My decision process required considerable soul searching and resulted in two long blog articles: The Wilder Side of Me and A Migration Celebration.

The Kaufman Field Guide (KFG) Series is an important body of work. Whereas there are a number of other worthy nature field guide series currently in print, Kenn’s series is built around the simple yet hard-to-actualize concept of crafting expert guides that are accessible to beginners. In my opinion the KFG series has accomplished that difficult task with an elegant brilliance.

The book I am co-authoring will be entitled, Kaufman Field Guide to Nature of the Midwest. I am primarily responsible for the botanical sections but will also be providing assistance in a number of other ways with the project. This book will be the second in KFG’s regional guides. The first in the regional series, Kaufman Field Guide to Nature of New England, will be released this October on the 16th — in three short weeks!

A Summer of Field Work

Co-authoring a field guide to nature requires not only prior knowledge but also lots of research. It is not sufficient to rest on past experience nor rely on previous adventures. Since the KFG series is crafted to be welcoming to the novice naturalist, you must attempt to view the world through the eyes of those who have yet to develop a keener awareness of the natural world. To do that, you must get out in the field and visit places that are likely to be visited — or could be visited — by your target audience.

From the moment I agreed to share a co-author spot with Kenn, I jumped into this project with both feet. It was not going to be acceptable to spend some time in the field. Instead, I knew I was going to spend a lot of time in the field — field time is what naturalists, ecologists, birders, botanists, environmental researchers, etcetera call time spent outdoors in habitats suited to your line of study.

Jeff stands in an old-growth field of Prairie Dock Plants (Silphium terebinthinaceum).

With North America experiencing a record warm and dry spring and summer, it has been a challenging field season to say the least. Capturing target species often required visiting multiple locations to find a specimen that was in healthy-enough condition to photograph. On the other hand, we were amazed by the resiliency of some species to thrive in seemingly-impossible conditions. Our efforts to get out in the field, even on the hottest and driest of weeks, were often rewarded with great finds.

The time April and I have spent in the field over the past four months has been nothing short of amazing. We visited numerous places throughout six Midwestern states taking notes, photos, and simply reveling in the breathtaking species richness, unique geology, and stories of the many local, state, and national parks that we visited.

Although I am co-authoring the book with Kenn, it has been a wonderful experience to spend so much time in the field with April. Nature is a core interest that brought us together almost twenty-five years ago. April is a very successful children’s book author focused on science and natural history. Our travels this field season will surely inspire her to pen another award-winning children’s book or two!

Part of the task I have assigned myself with this project is to photograph as many plant species in high-definition detail as possible. Next field season, in addition to revisiting a number of places, we will be covering the remaining areas of our territory to capture additional species. We will be visiting upper Minnesota, all of Ohio, lower Illinois and Indiana, and the eastern half of the lower peninsula of Michigan.

The map to the right shows the places we visited this field season.

Here are some statistics from our summer field season:

Miles traveled: 3,618

Photos taken: 11,919

Places visited: 42 over six states

Species photographed: 306

In our travels we have experienced some ecological jewels and have been awestruck by the beauty and resiliency of these ancient ecological marvels. Treading on virgin pieces of habitat — land that has neither seen nor felt the destructive forces of humankind (well, minus global climate change) — it is hard not to be moved.

Whereas we’re fortunate to have had the opportunity to experience nearly pristine habitats, we also have many fond memories from our visits on lands that have not be as fortunate to escape the plow, bulldozer, or poison. There is always a gem to be found if you know where to look. Many local and state parks and private preserves are working hard to reclaim and restore the land. We were honored to have met and been guided by a number of stewards who are the true heroes in the fight to preserve and return nature to its former grandeur.

A gallery of some places, species, and sights seen (click thumbnails for larger images):

Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore

The Federally-endangered Pitcher’s Thistle (Cirsium pitcheri) blooming on a Michigan dunescape.

Jeff walks a very-dry trail at Schlitz Audubon Nature Center near Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

iPhone photo of Jeff’s forty-pound photo pack. Try carrying that for ten hours each day in 100 degree heat up and down dune trails, into bogs, or through chest-high prairies.

A rare plant that is considered endangered or threatened in Illinois and Indiana, the Royal Catchfly (Silene regia) is stunning when in full bloom.

Why is it named catchfly? The calyx of each flower is covered with glandular hairs that exude a sticky substance. Small insects that land on this part of the plant often get trapped. Here yet-to-open flowers of a Royal Catchfly (Silene regia) demonstrate the reason for the name.

A beautiful eroded limestone rock formation within the forest of Picture Rocks National Lakeshore in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

An unusual orchid, Green-leaved Rattlesnake Plantain (Goodyera oblongifolia), in full bloom deep within the forests of Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore.

Clark Lake Bog in Tahquamenon State Park in the UP of Michigan.

Jeff carefully steps out on to the fragile — and potentially deadly — bog mat near Clark Lake Bog to photograph the scene. The area is punctuated with Tamarack trees (Larix laricina), a species closely associated with acidic bogs.

Jeff carefully positions himself and his tripod on a tenuous platform jutting out into Clark Lake Bog. What is he attempting to photograph? See the next image.

Success! I captured this other-worldly image of the small, carnivorous Spatulate-leaved Sundew (Drosera intermedia) as the sun began to set.

A macro shot of a beautiful Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina).

Am amazing Hummingbird Clearwing Moth (Hemaris thysbe) pollinating a Prairie Monarda (Monarda fistulosa).

Viper’s Bugloss (Echium vulgare), also known as Blueweed, is an attractive non-native plant that can be found on roadsides and waste places of limestone regions.

The individual flowers on the floral spike of the aptly-named Obedient Plant (Physostegia virginiana) will remain for a time in whatever position they are moved.

Count the deer flies. We were bitten by numerous deer flies and uncountable mosquitoes during our time in the field. How many deer flies do you see swarming around Jeff? At least 21.

It’s all about timing. We returned to this particular spot four times just to get this picture of a Michigan Lily (Lilium michiganense).

Unseen Benefits of This Endeavor

This field guide project has provided me with the opportunity to reconnect to the natural world in a way that I had been missing for some time. In retrospect, had I not accepted this project, I believe that the work I do in the world of technology would not be as meaningful to me going forward.

Besides providing me with an excuse (did I really need one) to spend more time out in nature, out in the field, this project enabled me to unplug from the metaverse, to hit the reset button and reevaluate what is truly important. It had become too apparent that I was spending more and more time in the metaverse, posting and chatting on various social channels in ways that truly did not prove useful to me nor my startup.

Although I claimed it was of little relevance to me, I did actually care about my social metrics — number of Twitter and G+ followers, my Klout score, etc. Whereas putting more time into the metaverse did maintain and sometimes increase my overall social metric rankings, the reality was that time spent in the metaspace did very little to improve my existence in the physical world. Breaking free of the shallow and often hollow trappings of the metaverse has allowed me to reassess what is truly important.

In the metaverse, there seem to always be an unlimited number of opportunities with which to get involved — open source projects, other startups, W3C groups, lengthy Google Plus threads. But few if any of these projects helped pay my bills nor did they result in long-term, meaningful work.

At first it was hard to unplug from the artificial and reinsert myself into the physical world. But after a week of immersive nature therapy, key synapses began to restrengthen. An important and essential core of my life began to reawaken.

I have made many friends in the metaspace and do strongly believe in the worth of open source and W3C groups. However, my involvement in various initiatives did not help my startup move anywhere closer to launch. If anything, it distracted me from my efforts.

You may be thinking that taking on the duties and responsibilities of co-authoring a field guide is an even greater hindrance to launching my startup. In a sense, that is true. However, as stated above, this project has rescued me from a deep dive into the metaverse. For that alone I am thankful.

Much of my writings about the Social Web and the Future of Humankind are rooted in my understanding and appreciation of the natural world and in particular ecology. However, I had become so immersed in the metaverse that I was spending fewer and fewer hours each week within nature and had reduced my time working on my startup. Instead, I was lost in conversations and thought. Although I would take breaks to walk in our native plant gardens, to go birding during migration, or to watch an occasional nature documentary, I was not tuned into the patterns of nature, I did not feel part of the natural world.

Have I Given Up On The Social Web?

Whereas I have not been working full-time on my current startup nor spending hardly any time on Twitter, Google Plus, or even on W3C committee work, as this field season comes to a close, I will be refocusing more of my efforts in these areas once again. Of course I will be putting in more field time next spring and summer and will be working on the field guide this winter — writing, photo sorting and editing, and range map creating.

With a very successful field season completed this year, and the reintegration of a core piece of myself, I feel confident that I can now juggle two disparate jobs — that of smartup entrepreneur and that of field guide author.

Coming in 2014!

Do you live in the Midwest, plan to visit the Midwest, or have friends or family that live in the Midwest? If so, look for my Kaufman Field Guide to Nature of the Midwest book to come out some time in 2014. I’ll keep you posted on a more precise release date.

A wondrous high-quality sand terraced dunal habitat on the western shores of the Mississippi River, Weaver Dunes Scientific and Natural Area is protected thanks to The Nature Conservancy of Minnesota.

In my article, The Wilder Side of Me, I ended with this thought that I think is appropriate to revisit:

E. O. Wilson says that, “Nature holds the key to our aesthetic, intellectual, cognitive and even spiritual satisfaction.” I have known this to be true for decades. But nature also holds the keys to our species future, keys that can only be utilized if we take the time to truly comprehend the marvel that is the Web of Life.

While you eagerly await the publication of my latest tome, I encourage you to step back a little from the metaverse and reengage and immerse yourself in the physical world. Take a walk at a local park during a lunch break, visit a state park this weekend, or just spend time in your yard or on your porch watching the marvels of nature. As our society accelerates toward increasingly-complex technologies, let’s not forget the foundation upon which our lives and livelihoods depend — the natural world.

May 19, 2012

A Migration Celebration

Some of you have undoubtably noticed my lack of presence over the past several weeks on the various Stream channels I participate in throughout the day. Whereas my cessation of postings on Google Plus and Twitter might be a relief to some of you, there is a logical reason that I’ve gone missing — I have turned my thoughts and gaze outwards to the physical world, shifting my focus away from the virtual world of tech startups and online social connections.

Why on Earth would I do this? It is spring migration!

Jeff in the field birding

The past several weeks, my wife April and I have been taking in the spectacle of animal migration — primarily birds. We’ve done this together each year for more than two decades. We are birders and proud of it!

A Great Nature Event

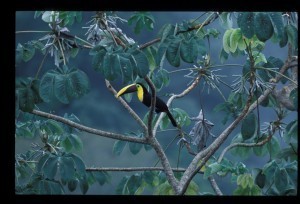

At this time of year in the eastern US, there is a free great nature event that anyone with a pair of eyes or even ears can experience. It is the time of year when part of the tropics returns to your backyard — with birds passing through on their way to prime breeding grounds further north. Literally billions of migrating birds make a dangerous, arduous journey from their wintering grounds, primarily in Central or South America, to their breeding grounds in North America (north of Mexico).

When thinking about the spectacle of mass animal migration many people may think of the massive movement of large ungulates on the Serengeti plains, or the throngs of North American Caribou on the Arctic tundra, or even the Humpback Whales’ long journey from wintering to breeding grounds. Yet the biennial migration of neotropical birds between the American continents may be the largest, if not greatest, mass animal migration on Earth. More than 250 species of birds are considered neotropical migrants. From hawks, to shorebirds, to waterfowl, to songbirds, these avian pilgrims make a twice-a-year journey from wintering grounds to breeding grounds and back.

The sheer number of migrating neotropical birds is astounding. It is estimated that approximately 5 billion birds migrate from the subtropics and tropics each spring to the United States and Canada. Even with the high mortality rates of adult birds during spring migration and while on breeding territory, the number of birds making the southward journey in the fall is probably greater as the adult birds are joined by juveniles.

Although you can experience bird migration in the western and central parts of the United States, if you live in the eastern third of the country (east of the Mississippi River), the number and diversity of migrating terrestrial-based bird species is significantly greater. Furthermore there are some gems of the avian world that are best seen in their eastern migratory flyways — primarily the group of birds generally called the New World wood-warblers as many of them require some degree of forest habitat for breeding.

Prothonotary Warbler

Northern Parula

Chestnut-sided Warbler

Blackpoll Warbler

Blackburnian Warbler

Black-throated Green Warbler

A Male Cape May Warbler

A Celebration of Migration

April and I have traveled all over North America and several other continents to study birds. But this time of year, we do not venture too far from our home as we let the birds do the traveling to visit with us. Over the past several years, we have been spending more and more of the spring migration time in northwest Ohio in what is becoming known as the Warbler Capital of the World. We spend much of our time in and around the Magee Marsh Wildlife Area, a world-renowned migrant trap: a place where, if conditions are right, large numbers and a great diversity of neotropical migrants may stopover on their journey north.

Birders at The Biggest Week

The past three years we have participated in a new birding festival known as . It is a celebration of migration, a wonderful place to see some of the jewels of the avian world, interact with birders from around the world, and meet people of all skill and interest levels. Literally thousands of birders flock to this location each year to take in the experience.

Beyond The Count

Although we do not keep year lists or even a life list anymore — a tally of the total bird species we have seen over a given time period and/or at a given geographic location — I did tally up the species we encountered during our most recent Biggest Week sojourn. We saw or heard a total of 154 species of birds — some of them were year-round residents and thus non-migratory species.

Whereas to hardcore, consummate birders that number may seem a little low given that over 230+ species were theoretically possible, to us the list, the tally, is not important. Once we hit 1000 bird species on our life list, we grew tired of chasing a number. We learned that what brought the most joy and happiness to our natural wanderings was getting to know a species better, getting to truly understand its behavior and the ecological niches on which it depends. That requires studying a bird well, observing it whenever you have the opportunity. It also requires getting to know its habitat — the plants, the prey, the biogeographic makeup of its niche. Thus finding rare birds is still fun, but what provides us with greater insight is the time we spend with species that we have seen many times before.

Although we keep field notes from each of our major trips and could come up with a total life list, we no longer enter any of our data into a birding database. Now, after two decades plus of tropical travel, we do not have a concrete count at where we stand — although I have a relatively good idea at where our life list probably stands.

Birding’s Cool And Birders Rock!

At The Biggest Week festival, we attended a keynote by world-renowned bird expert, naturalist, and field guide series author and editor Kenn Kaufman, who made a powerful, impassioned plea for the need to rebrand the activity of birding. I’ll attempt to encapsulate the essence of his speech in this section.

Jeff with his good friend Kenn Kaufman study a Prairie Warbler

Kenn remarked that the old-school view of birdwatchers as dweebs or nerds is passé. Birders come from diverse professional and personal backgrounds. From lawyers and doctors, to corporate executives and military Generals, to past Presidents of the United States and renowned conservationists, to scientists and school children of all ages, birders and the activity of birding are cool.

Birding is growing in popularity. This is a positive trend as there are real-world political, economic, and environmental consequences of humans gaining a better insight into and deepening their appreciation of the larger ecological connections that power our ecosphere.

Whereas avocations like running, tennis, golf, and even NASCAR may provide an important respite to participants, their benefit to the ecosphere is nil — in some cases these pursuits actually have a net-negative to the overall health of the planet. However pursuits such as birding that help participants reconnect to the natural world can accrue net-positives for the Earth over time. Birders’ activities can even provide useful scientific data for monitoring species and ecosystem health.

Prairie Warbler

Tower at Magee Marsh

A packed boardwalk of eager birders hoping to see a Golden-winged Warbler

Golden-winged Warbler that was just banded

The Wilder Side of Me

Although I spend much of my professional time thinking about and working on the issue of the technological transformation of society and our world, I lead a double life. These days my vocation is InterWeb technologist and technological futurist, yet my avocations are naturalist and ecologist. But in the past, these roles have been reversed.

If you’re interested in learning more, please read my recent post, The Wilder Side of Me.

Outside Resources

May 18, 2012

The Wilder Side of Me

From the title you may assume that this post will wax ineloquently about my party lifestyle (which I don’t have), possibly sharing some links to Facebook photos that I probably should have never set free into the InterWebs. You would be mistaken.

This post is an celebration of life — literally. It is a celebration of the wonders of the natural world and my seemingly-innate connection to it from an early age. It is an autobiographical essay about how I become a naturalist and ecologist.

Jeff photographing a Tree Frog on a Mayapple leaf

Although the vast majority of readers of my blog know me as an InterWeb technologist and technological futurist, I am as much a naturalist as I am a technologist. To me, the study of the natural world, the drive to understand the intimate connections of the Web of Life, and my fascination with the complex adaptive systems that power our ecosphere, provide me with unique insights into the technological challenges our species faces. Thus, being a naturalist makes me a better technologist and futurist.

An Exotic Bird Sparks My Imagination

From my earliest memories, I was fascinated by the natural world. Although I was a very sickly kid, that did not stop me from dreaming about animals, wishing to explore the wilds of my backyard. As a kid, I collected spiders and insects in jars so as to study them. I watched the Red-headed Woodpeckers that nested in our ancient Red oaks. I absorbed every wildlife documentary and Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom episode I could watch.

Red-headed Woodpecker

In summer my family would travel to Cape Cod, to Plymouth Beach. We would spend two weeks at the beach in a cottage that my mother’s sister, my aunt, owned. The cottage was on the shore with great views of the ocean. There I would explore the shoreline, study the intertidal pools, and try not to let my terrible asthma ruin my time.

When I was six or seven, I encountered an exotic bird at this cottage. I was transfixed by its song. I would spend long periods of time just sitting on the front porch, looking out over the ocean, and listening to the wonderful, melodious song of this bird. I had no idea what it was and only occasionally caught glimpses of it perched on a shrub down below me.

Each year when our vacation was over and we were jumping into the car for our long drive home, I would intently listen, trying to catch the song of this exotic bird one last time. Each year I looked forward to returning to the cottage so as I could hear the music of this marvelous creature again.

It was not until I was nine or ten years old that I figured out the mystery of this bird. One summer’s day in South Bend, I heard the mystical song of this bird at our home. I grabbed our Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America and finally identified my exotic quarry. It was a Song Sparrow! It turned out to be a rather common sparrow with a wide distribution throughout most of the United States and Canada. But for some reason, I had never heard it anywhere else except in Cape Cod — that was until now.

Although I had been fascinated by the Red-headed woodpeckers that nested in our yard and the Common Redpolls that showed up only in the wintertime at our feeders, it was this common bird, the Song Sparrow, that sparked my interest in and love of birds.

To this day whenever I hear a Song Sparrow singing I am transported back to the front porch of that cottage on Plymouth Beach. I am a six-year old kid once again and anything seems possible. To me, a Song Sparrow remains an exotic, mystical bird.

Song Sparrow

=”300″ height=”215″ class=”size-medium wp-image-1815″ />[/caption]With my growing interest in birds, it was not long until I started going out into the field (our neighborhood) to actively pursue them. When I was ten or eleven, my Father’s father, my grandfather, moved to Green Valley, Arizona. One summer we traveled to Arizona to visit him. I remember the evening when my father announced that he planned to wake up at 5:30 am to go bird watching in and around Mount Wrightson — one of the sky islands of Arizona’s Sonoran Desert region. That sounded interesting to me so I asked him if I could join him. Our first bird of the morning, and the first bird that I saw as an official traveling birder, was a Phainopepla — a Northern Cardinal shaped and sized bird but that is all black.

Lessons From A Big Brown Bug: I Started Fifth Grade With Four Insects In A Jar

The summer before fifth grade, my classmates and I were sent a letter from our soon-to-be science teacher instructing us on the insect collection we were to assiduously begin while we were on summer break. We had to collect a minimum of 30 insects making sure that we had a good variety of species. I refused to collect any insects — at least in the way we had been instructed — in a jar partially filled with alcohol.