Tarek Osman's Blog, page 4

September 23, 2016

The Future of European Muslims – An Essay

But a slow pace can be dangerous. It makes ordinary people gradually come to accept ideas and “realities” that, were they to be introduced suddenly, would have elicited acute rejections.

This characteristic has been a key factor in the rise, over the past two decades, of far-right parties in the Continent and the UK. Slowly, what seemed shocking a decade ago – say that Austria almost elected an extremely far right politician as president, or that such parties would command significant presence in European parliaments – came to be seen as normal outcomes.

For some, this phenomenon is a threat to the liberal-democratic order upon which post-Second World War Europe was built. In this view, the rise of the far right is not just a consequence of populism at a moment of economic weakness; it is a peril to what Europe came to mean in the last few decades: a sanctuary of freedoms, political and civil rights, plurality, and individuality, all anchored on, supposedly, deeply held lessons gained from colossal mistakes that cost the lives of tens of millions of people.

Other Europeans see Europe differently. Wide sections of the middle and especially working classes, regard Europe not as a political project situated in a historical context, but as a social order: a set of shared values and various yet relatively similar ways of living. Many Europeans won’t be able to clearly define what “European” means; but they would be able to identify that which, for them, does not culturally fit their Europe. And so, for a significant percentage in these social segments, the rise of the far right in Europe is a consequence – or reaction – to the entrance of new, and what they sense are culturally unfit, elements in European societies.

In this view, these elements are non-ethnically European, and especially Muslim, immigrants. For at least a decade now, these feelings about cultural fitness have been interacting with gloomy economic trends in large parts of Europe and have already created strong nationalistic – and nativistic – political currents that see non-ethnically Europeans, and especially Muslims in Europe, as a problem.

This is a different view from the one held by those who regard Muslims in Europe as a threat. The latter get most of their facts about Islam, Islamic history, and Muslim communities in Europe, wrong; and generally they have antagonistic positions towards Islam and Muslims. But those who see Muslims in Europe as a cultural problem (not a threat) have no quarrels with Islam as a religion or with Muslims as individuals. However, they believe that the inherent values that are engendered within the largest segments of Muslim communities – in or outside Europe – are incompatible with the way of life, social norms, mannerisms, and indeed values, of European societies. And so, from their standpoint, the rise of the far right in Europe, though highly distasteful, can be explained as a (crude) defence mechanism against elements that the European body is uneasy about.

Those who invoke the rise of the far right as a threat to Europe’s liberal democratic order, typically, see immigration as one problem among others, in the complex challenges facing the European project of the past half century. And so they put immigration in perspective: about 15 million Muslims, the vast majority of them peaceful, productive members of society, in a continent of almost 500million people. But for the large social segments who are less obsessed with the ‘European project’, immigration, and that specific concern of cultural fitness, is the single most important challenge they want addressed – now.

Some factors make the urgency understandable. After half a century of slow but continued growth of Muslim communities in Europe, neither Europe nor the majority of European Muslims have figured out a workable and sustainable emotional link between the two sides. Many, especially in Francophone and Germanic Europe, continue to see Muslim communities as immigrants, outsiders who even if they would never leave, would also never become part of “us”. For most people here “us” is not a race-based collective; it is the reservoir of society’s cultural heritage. On the other side, many European Muslims, especially of the elder generation that had settled in Europe in the period from the 1960s to the 1980s, were keen to acquire and pass to their children European passports, but they abhorred that those children would “God forbid, become, Europeanised”.

That emotional detachment – from both sides – is becoming more fraught. Unlike their parents and grandparents, second and third generation European Muslims are not overly sensitive to the apprehensions of the majority of their fellow citizens. They see the cities and towns they grew up in as their homes. They believe – and have solid legal, political, and moral reasons to back them – that they have equal claim to Europe as ethnic Europeans do. But political correctness aside, that belief, confidence, and justified sense of entitlement is seen, from the other side, as another reason to address the “immigration problem” now. The segments that see most Muslims as culturally unfit outsiders want a strict and quick limit on the number of “immigrants”, and especially Muslims, who would be “at home in our” societies. It is easy to succumb to knee-jerk accusations of bigotry. But that does not alter the fact that these feelings are increasingly one of the most powerful trends in European politics.

The second reason justifying the urgency is that all major integration and assimilation strategies of the past few decades seem to have failed. Time was supposed to bring about a meeting of minds, values, and lifestyles. For most Europeans this meant that the Muslims in their midst were expected to gradually discard the world-views of their original countries and adopt the values of the societies they chose to come to. Despite the cultural condescension inherent in that view, it was reasonable to assume that second and third generation European Muslims would indeed transcend many cultural barriers and internalise a lot of the values and mannerisms of the societies they grew up in. Some did. Many demonstrated the classic desire for success, characteristic of minorities all over the world, and so we see in Europe a lot of doctors, lawyers, and professors (especially in scientific disciplines) of Islamic background. But the majority, even in the second and third generations, did not internalise the values of their new societies.

Partly, this was the result of the fact that most of the Muslim migrants who came to Europe in the period from the 1950s to the 1980s belonged to the lower middle, working, and poor classes of their original societies. Their exposure to their home countries’ experience of modernisation (in the century from the mid 19th to mid 20th century) was limited. And so, they were particularly susceptible to the cultural shock of being in-rooted in extremely modern, secular, liberal, and individualistic societies.

Partly, it was the fault of the European elite that wanted them to come as cheap labour, especially in the two decades after the Second World War, but never invested in enabling them to integrate and assimilate. This was understandable in the 1950s and 1960s. But, by the 1980s and 1990s, it became one, among several, confirmations that many in Europe’s elite defined Europe narrowly; they failed to imagine a European norm that transcends the foundational culture.

The third reason is that most of the ‘solutions’ that seem to have some authority, the ones that European Muslim intellectuals put forward, have limited resonance amongst most European Muslims. These ‘solutions’ delve into Islamic theology to prove, both, to the large European audience that Islam is peaceful, tolerant, and has no quarrels with secular modernity, and to European Muslims, that they can find, within the recesses of Islamic jurisprudence, flexible answers to any dilemma they might have about being Muslims living in today’s Europe. Many of these interpretations are selective and could easily be refuted. But the real flaw of this approach is that it assumes that a significant percentage of Muslims are waiting for philosophically rich discussions of centuries-old concepts, put forward by scholars they hardly have heard of, who supposedly have the ability to forge interpretations of what a European Muslim means, or how he or she ought to see his or her identity, and live life. It is amazing, and yet fully understandable, that a cottage industry has grown around that illusion.

Actually, these ‘solutions’ exacerbate the problem. Approaching the place of European Muslims in their societies through theology, even if by the most enlightened Islamic scholars, entrenches the distinction between Muslims and the rest. It is also misguided. It frames the question as: how can we reconcile the most dominant interpretations – which are far from the most enlightened – of fourteen-centuries old religious rules with the norms and values of the most liberal and modern group of societies in human history. This framing addresses a different problem.

And then, of course, there is militant Islamism. Whether organized or the acts of “lone wolves”, the more Islamists attack Europe, the more difficult the positioning of European Muslims would be. The majority of Europeans will not condemn their fellow Muslim citizens as guilty by association (though increasingly, some do). But feelings of unease and anguish will deepen.

Because of the declining competitiveness of most European economies relative to Asian ones and concurrent technological advances, joblessness in Europe will increase and living standards will suffer. Expectations, however, will not adjust quickly. And so, many in Europe will lose both, the resources and patience, they have had when dealing with intractable problems, such as immigration.

The changing nature of European politics will exacerbate the problem. Many talk of a leadership crisis in Europe. But irrespective of assessments of personalities and capabilities, European politics will become more prone to populism. As most European societies grow older, and face adverse economic conditions, young Europeans will face mounting financial pressures. The gap between their economic expectations and the reality of their lives will become increasingly painful. Many will grow disillusioned with their countries’ political-economic systems. Anger, and the need for a scapegoat, will rise.

The far-right and far-left will become much more powerful across Europe. Many European legislatures and governments will face difficult situations in which wide segments of the electorate will demand discriminatory policies that favor ‘the natives’. And whilst some European countries have strong and deeply entrenched cultures of fairness and equality, many will succumb to the pressures from below. As a result, there might be a rapid change in the relationship between the state and some of its citizens, especially European Muslims. State neutrality with regard to race and religion could face a serious shock.

Top-down solutions will not work. Young European Muslims have no choice but to take ownership of the problem. The widespread abdication of responsibility many European Muslims have towards their own future will give rise to colossal challenges, and potentially threats, to their presence in Europe.

Three points could be a start. One: stop focusing on Islam. There are, at least, half a dozen major interpretations of the key theological foundations of this 1500 year old religion. And for each, there are different views on how to reconcile that interpretation with secular modernity. Anyone with a decent command over Islamic history (which spanned three continents and vastly different political and socio-economic epochs) and an above-average exposure to its multiple disciplines can pick and choose from a stupendously rich heritage, to forge an argument for or against “Islam’s” compatibility with secular modernity. All of these arguments are, by default, selective and subjective. None will be the final word. And it won’t make any difference, in terms of credibility, or resonance within European Muslim communities, if some European, Arab or Islamic governments endorsed the most flexible and liberal of these arguments.

Two: focus on Islamism: the different manifestations of the myriad of interpretations of Islam in politics, legislation, social dynamics, and identity. Invariably, these manifestations are functions of bottom-up socio-economic and country-and-often-community-specific circumstances. Local cultures play a crucial role in shaping and developing these manifestations. And in the context of the situations of European Muslims, a lot of the heritage and circumstances surrounding – and making – the local cultures – pose problems to any cultural reconciliation with today’s Europe. But only through understanding these local versions of Islamism (in different European societies) would serious and practical solutions emerge. And almost certainly for these solutions to be implementable, they would have to come from youths within these local Muslim communities.

And third: apply the emerging ideas through working with the local civil society – not state vehicles, religious authorities, or political parties. The objective is to get the small educational, occupational, entertainment, and other social organizations that serve local Muslim communities to interact with counterparts that serve the ‘rest’. ‘Communities’ is the key word here. Hundreds of thousands of European Muslims have rich, varied, and multi-faceted interactions with their wider societies, but many of those are at the upper (affluent) segments of European Muslim communities, which as a whole, often have shockingly limited exposure to the ‘rest’. Working with these local civil society organizations would not only expand Muslims’ realm of interactions with their wider milieus, but also channel these interactions away from top-down structures (including political elites) who have nothing to offer, and whose interventions are likely to complicate these community-based interactions. Gradually, significant percentages of young European Muslims (primarily at the lower socio-economic segments of Muslim communities) will build and gain trust, become less detached, and experience commonalities with their countrymen and women. This is a key basis of any collective identity. As simple as this might sound, it has not taken place on any major scale in almost any European country with a sizable Islamic presence.

Community leaders and financially successful young Muslims (the thousands of high earning professionals) should support artistic work and initiatives, in particular. Because of many of the background factors highlighted above, the first generation of European Muslims (in the past four decades) had a limited contribution to mainstream European art, philosophy, and culture in general. This is changing, though at a very slow pace. And the vast majority of emerging Muslim European artists tend to focus on amusement and farce, for example stand-up comedians in the UK. In addition, in the past two decades, the vaguely defined sensibilities of Muslims, and especially European Muslims, have set them apart as a group that should be protected from freedom of expression. All of this meant that, despite half a century of being a component of some of the largest and most dynamic European societies, Muslims have not yet left a mark on Europe’s contemporary collective consciousness. This is particularly saddening given that the presence, integration, and future of European Muslims have become a key issue in Europe’s socio-politics. That is why Muslim communities should strongly encourage their young’s artistic endeavors, experimentation, and entrepreneurship. Art – in its broadest definition – has always been the most effective, and noblest, medium through which the ‘other’ manages to shed the layers of alienism and the ‘rest’ sees the depth beneath the veneer.

All of this would not magically solve the problems that have bedeviled the situations of European Muslims. But they could mitigate against the host of emerging challenges. On the contrary, characterizations of “Islam”, empty political talk that eschews real problems, and rhetoric steeped in theology will yield nothing – as has been the case in the last few decades.

If young European Muslims fail to take ownership of their future in their societies, they might find themselves in an acute predicament, sooner than many of them think.

You can also read this article at this address:

http://yalebooksblog.co.uk/2016/09/23/the-future-of-european-muslims-an-essay-by-tarek-osman/

August 9, 2016

Tarek Osman’s interview with Lebanon’s Future TV English on Muslims in Europe

Tarek Osman’s interview with Lebanon’s Future TV English on ISIS, Middle Eastern politics, and Lebanon

May 24, 2016

Audio of Tarek’s interview with Canadian Broadcasting Corp on Redrawing the Map of the Middle East

May 23, 2016

Tarek Osman with Alaa el-Aswani, Hugh Kennedy, and Wendy Steavenson on BBC’s Start the Week

May 11, 2016

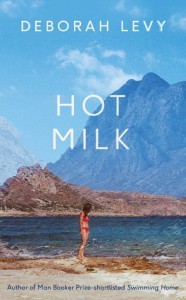

Review of “Hot Milk” by Deborah Levy

A mother and a daughter in a town in southern Spain in August. The mother, unable to walk, feels being there, even if on a medical trip, even if the Mediterranean for her is a mere view from the terrace of the chalet they rented, is a test – potentially in liberation; does she want, is she able, to embrace that liberation, or is it too difficult to abandon one’s comfort zone of anger? On her first day, the daughter, Sophie, rushes to the sea, is stung by shellfish, or the “Medusas” – do the Spanish call them that because their long limbs resemble the Medusa’s hair, or is the sting a metaphor for shocking stares that will stone both, mother and daughter.

“Hot Milk’s” main character, Sophie, takes us on a journey of two hundred pages to graduate herself from that designation we first meet her as – the daughter – to emerge as a full human being. Sophie’s ’emergence’ takes place as she unfolds layers of herself, by airing her shortcomings and grasping new glimmers of potential. At the beginning, most of Sophie’s disappointments are at herself; as the pages – and encounters – accumulate, her disappointments become richer; those at herself get entwined with those at circumstances and at others. In a book full of introspection and subtle analysis of wants and needs, it is remarkable that these heaps of disappointments, and in turn “Hot Milk”, bear no bitterness. Disappointments make Sophie look for different routes, ones that slowly seduce us, the readers, to turn the pages, to listen to her thoughts, see her perspectives, and to join her in her journey to lean away from the disappointments towards the potential.

This is not a book about taking control. It is not about empowering oneself. And it is the farthest thing from a subtle feminist argument. It could be about acceptance, of oneself. At moments, “Hot Milk” seems to hypnotize us into believing that the best journeys are the ones in which we lose control. Perhaps it is fitting. The novel unfolds on the shores of the Mediterranean, where for centuries local myths (on the sea’s northern and southern shores) venerated drifters: those who appear out of nowhere, sons and daughters of the waves, who are themselves on journeys, and who, in the courses of these journeys, meet, illuminate, and often set free, others.

Equally plausible, the novel could also be seen as an attempt to escape being a drifter in life. Sophie comes to al-Meria (the Andalusian town whose name means “the mirror” in Arabic) and sees her life as following her mother, attending to her as she (the mother) seems to be succumbing to a mental paralysis, a resignation of the will. Sophie has abandoned her doctorate; has been living in a small room above the cafe she works in in London. None of that was supposed to be milestones of her career, landmarks of her life. None of that is truly hers, or truly her. She has been drifting. And it is here, in al-Meria, that she stops being a drifter. She makes decisions: from confronting her mother’s illness to connecting with her anger, insecurities, and libertinism. Sophie spends a lot of time on the pages of “Hot Milk” walking semi naked, on beaches, kitchens, makeshift rooms, and even in the desert. And yet, she ceases to be a drifter.

The setting of the novel has a meaning. The author, Deborah Levy, (most likely) intended al-Meria to reflect Sophie’s thoughts, her inner life. But there is also a reason for being on the Mediterranean in August: a milieu of freedom, joy, and sensuality. Sophie’s mind finds space to roam, in the same way that her mother’s legs – hesitating between walking and the wheelchair – are seduced by the beach, to move, to stroll. The geographic exile, even if only for few weeks, in a welcoming setting, sets emotions and desires free.

“Hot Milk” has a dark side, though. There is the vulnerability of those in geographic and emotional transit, those who feel they have a short window of time in which to explore what they have wanted, yet never dared, to discover; and those who have not yet figured out what they want. For Sophie, these range from a desire to pursue her dreams: owning her time, not being tied to her mother’s life of dependency and illness, sleeping with a carefree student who peeks at her, to finishing her PhD in America. Deborah Levy does not just show that vulnerability in a charming way, one that encourages the reader to let go of his/her inhibitions. She also – and with matching relish – uncovers the anxiousness that comes with being in the midst of emotional transition. Sophie does not regret any decision she acts on in “Hot Milk”. But in thinking about her wants, and in acting on them, she exposes wounds that were long covered in her normal life, before she came to al-Meria to see herself mirrored in front of the piercing eyes of her brain.

And then, there’s fear: “Fear of failing, falling, and feeling”. More anxiety: at seeing previously unchartered depths of one’s insides, at taking risks only to discover that leaving comfort zones can ascend us to where we want, or leave us to fall without the safety net of ignorance of who we truly are. And with all of that, there’s the fear of feeling: love and hate, longing and repulsion, wanting and discarding – to others, especially very close ones, and crucially to our own selves.

Deborah Levy exposes her characters’ myriad of sufferings. Suffering from unrealized aspirations, from confusion at what to do in the face of mounting difficulties, from lacking love, from finding love and feeling unable to achieve it, from the insecurities that come from achieving it and fearing to lose it, from fraught relationships with parents, from confronting unfamiliar circumstances that seem to be – or that our minds interpret them as – threatening, and, painfully, suffering from being disappointed with ourselves. Is it true that women suffer that last feeling more than men do? And if true, does it reflect more demanding minds or more sensitive dispositions, or both? “Hot Milk” leaves the feelings and the questions it raises in the reader’s mind, hanging. Deborah Levy is a pragmatic author; though “Hot Milk” is about interior lives, it is not concerned with answering the questions it compels our minds to ask. Deborah wants us to move on with her characters. They feel, we think (for few seconds after we raise our eyes from the novel’s pages), then they and us (the readers) move on, to more conversations, vulnerabilities, fears, and inevitably other questions.

Moving on is a way for the characters, and for us, to pretend not to notice the feelings “Hot Milk” stirred. And yet the commonality of this tendency of not-to-notice, the fact that we as readers immediately get what Deborah Levy is telling us, lies at the heart of what this book is about: that insecurities, introspection, fears, suffering, and feeling lonely are widely shared. We get what this book is about because Sophie is not particularly unique. Her emotions resonate with readers. “Hot Milk” is about the hope, though rarely the conscious act, of most people to have a life story, a real story that contains interesting characters, entails progress, is rich with raw emotions, that connects with base wants, and yet that is not devoid of meaning. This transcends desire. It is a need.

Abandoning that need creates rage. Losing the plot of what one’s life is about engenders rejection of circumstances, the first step towards descending into victimhood. Sophie’s mother is a prime example. That’s until Sophie challenges that narrative, by changing her mother’s circumstances. I will not be a spoiler. But perhaps one of the interesting features of “Hot Milk” is Deborah Levy’s ability to weave interesting events, sharp twists of the plot, into a book that is essentially a flow of introspection. There’s a bit of Woody Allen in Deborah Levy.

“Hot Milk” does not feel like a conceived, structured, and executed novel. Some critics scoff at that fluidity. Many consider it a post-modern prose that lacks the thinking depth upon which great literature stands. To a reader, however, that fluidity is the exact point of successful fiction: that you forget you’re reading a novel and be transported to the place, time, and milieu where the story unfolds. And if, as is the case in “Hot Milk”, the novel is wrapped in luscious wording (crucial if a writer is to avoid crossing the fine line between a sensual flow and a crude register), the transportation acquires an additional layer of joy.

March 19, 2016

Rereading the Yacoubian Building

Erected in the mid 1930s in Cairo’s newly Europeanized centre, the building is an architectural jewel, and was then the home of a multitude of Egyptian pashas, wealthy Europeans, and star artists. Al Aswany uses a set of characters and crucially the space—the building and its surroundings, Cairo’s downtown—to dissect society at the beginning of the twenty-first century, and how it became what it is.

Al Aswany’s judgement is uncompromisingly clear. As Egypt moved from its cosmopolitan, liberal age in the 1930s and 1940s towards the tumult of Arab nationalism in the 1950s and 1960s, the original residents of the architectural jewel quietly leave, mostly for self-imposed exile in Europe and the United States. A new elite drawn from the new cadres of power replaces them. These residents effect a gradual but conspicuous change in the look and feel of the building: less European, less cosmopolitan, and though Al Aswany does not spell it out, less refined.

By the 1980s and 1990s, Egypt’s arriviste ruling classes also leave for the new suburbs and gated communities far away from Cairo’s pulsating center. A melange of different social groups moves into the Yacoubian building: from affluent traders, to migrants from Upper Egypt and the Nile Delta who live in small “nests” on the building’s roof. The remains of a bygone era’s refinement struggle to survive in that crowded social hive.

Al Aswany strips down the contrasts between that marginalized, barely existing old refinement, and the now ubiquitous “monstrosity” through two specific characters: Zaki Bey, the Paris-educated son of a pasha, who even in his old age relishes the joys of life, and “Hajj” Azzam, a man who had started his life shining shoes close to the Yacoubian building and rose to own several commercial enterprises in downtown Cairo, including in the building itself. Apart from his self-gratifying exploits, Zaki has no real work. He lives his life in and around the Yacoubian building; he breathes the memories of his youth in the paradise lost of downtown. Azzam, on the other side, does not indulge in this downtown. It reminds him of his humble beginnings; he avoids old memories, disconnects time from space And as we come to know, he is in fact a drug dealer. One is idle, the other a criminal.

A key reason why the novel resonated so strongly with hundreds of thousands of Egyptian readers was that its characters were instantly recognisable. We all knew of a few Zakis, and many Azzams. Rather than being a journey, or even a tale where we (the readers) want to know the ending, the novel was a confirmation of what we have felt for years about our own society.

But Al Aswany is not a simple writer. He laments the liberalism and beauty that were; he abhors the fake religiosity, ugliness, and uncouthness that are. But he does not merely confirm what his readers already feel. When it was published, The Yacoubian Building expanded the way society looked at its recent past, transforming the narrative from one in which the people blame authority (power, the regime, recent political heritage, etc.) for society’s decline, to one in which the people reflect on the present they have created.

Al Aswany, however, doesn’t absolve the political elite that controlled Egypt at the time. He gives us El-Fouli: a symbol of oppression and corruption, and the sleazy blur between power and wealth. But El-Fouli is not there to take the blame. In the novel, he is hardly responsible for any of the ugliness, injustice, and chaos that Al Aswany unfolds in front of us. Al Aswany downgrades El-Fouli from being the villain, to being merely a product of the culture of decline that dominated Egypt in the second half of the twentieth century.

The real culprit is society—us, the readers. We have lost what was there and replaced it with what exists now. In this sense, The Yacoubian Building is not a struggle between good and evil, morality and depravity, or right and wrong. It’s a rich novel that shows us the beauty and ugliness within ourselves, as Egyptians. And, with quiet coldness (Al Aswany is a dentist), condemns us as the real culprits of what has happened to our society.

Reading The Yacoubian Building in 2016 feels different to reading it when first published. Egypt’s 2011 uprising could be seen as an expression of anger at the inheritance of the second half of the twentieth century. Today the picture is different. Now, a reader would inevitably contextualize the novel in the events and polarizations of the past five years. An optimist might look at that as evidence that large segments of Egyptians, especially within its youth, are acutely dissatisfied with their society’s recent history and its trajectory.

But reading the novel in 2016 could lead to another conclusion. The Yacoubian Building, and the novel’s bestselling success, could be a barely disguised condemnation of society. Death dominates the last section of the novel, and crucially none of the novel’s key characters arrives at a happy ending or even contentedness. This could mean that the anger that many felt towards their present and past, and the hope that sprang from that anger—to shape a vastly different future – have evolved into despair.

Ambiguity enriches the experience of reading any novel. The beauty of literature lies in the boundaries it opens for our minds to interpret a narrative, fall in love with a standpoint, or vehemently reject a view. What was certain about The Yacoubian Building when it was published over a decade ago, and remains true today, is that it forces us, as Egyptians, to think about ourselves and what we have done (and continue to do) to our society.

You can also read this article at this address:

http://www.thecairoreview.com/tahrir-forum/rereading-the-yacoubian-building-a-decade-later/

إعادة قراءة «عمارة يعقوبيان

لم يكُن التطوُّر الذي شهده العالم العربي في السنوات جاء حُكمُ الأسواني شديد الوضوح؛ فبعد انقضاء العهد الكوزموبوليتاني الليبرالي بمصر في ثلاثينات وأربعينات القرن العشرين، وتحوُّلها إلى القومية العربية في الخمسينات والستينات، رحل سًكَّان التحفة المعمارية عن مصر، فارضين على أنفسهم منفىً اختياريًا في أوروبا والولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. وجاءت لتحل مكانهم، النخبةٌ الجديدةٌ من كوادر السلطة التي ظهرت بعد سقوط الملكية. أدى هذا التغير التدريجيٍ في قاطني العمارة الى تغييرٍ واضحٌ في شكل المبنى وروحه. في فترة وجيزة صارت «عمارة يعقوبيان» أقل أوروبيةً، وأقل عالميةً، و- رغم أنَّ الأسواني لا يقولها صراحة – أقل رُقيًا.

وبحلول الثمانينات والتسعينات، حدث تغير أخر. غادرت الطبقات من كوادر السلطة إلى ضواحي جديدة بدأت في الظهور في تلك الفترة، ضواحي بعيدة عن «وسط البلد» النابض في قلب القاهرة. هذا التغير أدى بدوره الى ظهور خليطٌ من مختلف الفئات الاجتماعية في «وسط البلد» – ومن ثم في عمارة يعقوبيان. كان هذا خليطاً من التُجَّار الأثرياء إلى مُهاجرين من الصعيد والدلتا يعيشون في «أعشاش» صغيرة على سطح المبنى. ومع مرور الزمن أصبح على بقايا الرُقيِّ الذي ولَّى عهده الصراع من أجل البقاء في تلك البيئة الاجتماعية المزدحمة.

جرَّد الأسواني التناقضات بين الرُقي القديم -الذي أصبح مُهمَّشًا وبالكاد قائمًا – وبين «المسخ» الذي حلَّ الآن في كل مكان، عبر شخصيتين محددتين: «زكي بيه»، ابن الباشا المُتعلِّم في باريس، الذي يتمسَّك -حتى في شيخوخته- بتذوُّق مباهج الحياة، و«الحاج عزَّام»، وهو الرجل الذي بدأ حياته بتلميع الأحذية بالقرب من عمارة يعقوبيان لينتهي مالكًا عدة محال تجارية في وسط القاهرة، بما في ذلك في عمارة يعقوبيان نفسها. وبصرف النظر عن رقي «زكي بيه» وأيضا بصرف النظر عن انغماسه في ملذَّاته، فإنه بلا عمل. يعيش زكي حياته في عمارة يعقوبيان وما حولها؛ يتنفَّس ذكريات شبابه في جنة وسط البلد المفقودة. أمَّا عزام فلا ينغمس في وسط البلد تلك؛ فهي تُذكِّره ببداياته المتواضعة. إنَّه يهرب من ذكريات قديمة محاولًا فصل الزمان عن المكان. وكما نعرف لاحقًا فإنَّه تاجر مُخدرات. واحدٌ كسولٌ عاطل؛ والآخر مجرم.

كان أحد الأسباب الرئيسية في تردُّد صدى الرواية بين مئات الآلاف من القراء المصريين هو أنَّ شخصياتها كانت واقعيةً وحيَّة؛ فكُلنا قد قابَلَ في حياته بعضًا من أمثال زكي، والكثيرين من أمثال عزَّام. لا تسعى «عمارة يعقوبيان» إلى أن تكون رحلةً، أو حتى قصةً نريد نحن -القراء- أن نعرف نهايتها. إنَّها تأكيدٌ لما شعرنا به لسنوات تجاه مجتمعنا.

لكن الأسواني ليس كاتبًا بسيطًا. فهو يتحسَّر على انقضاء زمن الليبرالية والجمال، ويمقت التديُّن الزائف، والقبح، والفظاظة التي أصبحت سمات الحاضر، لكن روايته ليست مُجرَّد إقرار لما يشعر به قراؤه. عندما نُشرت «عمارة يعقوبيان» وسَّعت نظرة المجتمع المصري إلى ماضيه القريب، لتُحوِّل السردية من شعبٍ يلوم السلطة (الحكومة، والنظام، والتراث السياسي الحديث، إلخ) على التدني الذي أصابه، إلى سرديةٍ يتفكَّر فيها المجتمع في الحاضر الذي صنعه الناس بأنفسهم.

ولكن الأسواني لا يعفي النخبة السياسية التي سيطرت على مصر في ذلك الوقت من المسؤولية؛ فقد أعطانا في روايته «الفولي» رمزًا للفساد والحدود الغائمة بين السلطة والثروة. لكن دور «الفولى» في الرواية ليس تحمُّل المسؤولية عن كل شيء؛ فهو بالكاد مسؤول عن القبح، والظلم، والفوضى التي تتكشَّف أمامنا بين سطور الأسواني التي لا يؤدي فيها «الفولي» دور المذنب. انه هنا مجرَّد نتاج للتردي التي ساد مصر في النصف الثاني من القرن العشرين.

المذنب الحقيقي هنا هو المجتمع، أي نحن القراء. لقد فقدنا ما كان وأبدلناه بما حولنا وبين أيدينا الآن. وبهذا المعنى، فان «عمارة يعقوبيان» ليست صراعًا بين الخير والشر، أو الأخلاق والفساد، أو الحق والباطل. إنَّها روايةٌ غنيةٌ تكشف لنا الجمال والقبح في داخلنا نحن المصريين. وببرودٍ طبيب الأسنان (مهنة علاء الأسواني الأولى) يُديننا نحن القراء باعتبارنا السبب الحقيقي فيما حدث لمجتمعنا.

إنَّ لقراءة «عمارة يعقوبيان» في عام 2016 شعورٌ مختلفٌ عن قراءتها حين نُشرت أوَّل مرة. يُمكن أن ننظر إلى انتفاضة يناير 2011 في مصر باعتبارها صرخة غضبٍ ضد ميراث النصف الثاني من القرن العشرين، الميراث الذي أوجد ونما التردي الحزين الذي عاشته مصر. اليوم تبدو الصورة مختلفة؛ فالقارئ حتمًا سيؤطر الرواية بالأحداث والاستقطابات التي شهدتها السنوات الخمس الماضية. قد يرى المتفائلون في ذلك دليلًا على أنَّ قطاعات واسعة من المصريين -الشباب بخاصةٍ- غير راضين عن تاريخ مجتمعهم الحديث ومساره. وفي هذا طاقة تغيير وارادة بعث.

ولكن قراءة الرواية في عام 2016 يُمكن أن تؤدي إلى استنتاج آخر؛ فـ«عمارة يعقوبيان»، ونجاحها الكبير على مستوى المبيعات، يُمكن أن يكون إدانة صارخة للمجتمع. ليست مصادفةً أن الموت يسيطر على القسم الأخير من الرواية. وأيضاً ليست مصادفةً أنه لا يصل أيٌ من شخصياتها الأساسية إلى نهايةٍ سعيدةٍ أو حتى مُرضية. قد يعني هذا أنَّ الغضب الذي يشعر به الكثيرون تجاه حاضرهم وماضيهم، والأمل الذي أطلقه هذا الغضب في تشكيل مستقبلٍ مختلفٍ تمامًا، قد استحال يأسًا.

يُثري الغموض تجربة قراءة أيَّة رواية؛ فجمال الأدب يكمُن في الحدود التي يفتحها لعقولنا لتفسير سردٍ بعينه، والوقوع في حب موقف، أو رفض وجهة نظر. ما هو مؤكَّدٌ أنَّ «عمارة يعقوبيان» قد فرضت علينا، كمصريين، أن نُفكر في أنفسنا وما فعلناه (ونواصل فعله) في مجتمعنا. كان هذا صحيحًا وقت نشر الرواية؛ ويبقى صحيحًا اليوم.

Tarek Osman's Blog

- Tarek Osman's profile

- 17 followers