Matt Ruff's Blog

September 8, 2025

60

Still the coolest thing to happen to me this year

Still the coolest thing to happen to me this yearI am sixty years old today.

It’s been a wild decade. On this day in 2015, I’d finished copyediting Lovecraft Country and was waiting on the first-pass galleys. The book was due to be published in February and I was hopeful that it would do well, but I had no idea what was waiting for me just a few months down the road. It must have been April when I got a call from Matthew Snyder at CAA saying that Jordan Peele wanted to talk to me. “He’s mostly known for comedy, but apparently he’s looking to break into horror.” No kidding.

The Big Phone Call with Jordan Peele and Misha Green took place on May 5, 2017, and things just snowballed from there. Fast forward to 2019 and I was in southwest Chicago, dressing up as an extra and staying up all night to watch the filming of the big block party scene for the pilot episode of HBO’s Lovecraft Country. The show debuted on August 16, 2020, in the middle of the pandemic—we held a socially distanced viewing party in a friend’s yard on Mercer Island—and three weeks later I cracked the New York Times bestseller list for the first time ever (great timing, as COVID had eaten the publicity tour for my more recent novel, ). And while the show only ran one season, its success gave me the opportunity to write my first-ever sequel, The Destroyer of Worlds.

Me dressed as a Chicago fireman for the Lovecraft Country pilot episode; Lisa meets Courtney B. Vance during the filming of episode 7.

Me dressed as a Chicago fireman for the Lovecraft Country pilot episode; Lisa meets Courtney B. Vance during the filming of episode 7.…so that was fun.

My own fifteen minutes of fame notwithstanding, it’s been a rough decade for the publishing industry. The most recent Really Bad Sign was the announcement by the Associated Press that they won’t be doing weekly book reviews anymore, as the audience for those is too low to make them cost-effective. I know I should be more worried about this, but the thought I always come back to is that telling stories was never a practical way to make a living, and yet somehow I’m still doing it after all this time. And a nice side-effect of Lovecraft Country‘s success is that it’s opened up some new opportunities for me that may help keep the lights on even if this whole “literature” thing turns out to have been a passing fad.

This was also the decade in which I got my first taste of what it means to get old. Your exact mileage may vary, but somewhere around fifty, your body parts start going out of warranty, and by fifty-five, any meet-up with friends of a similar age is likely to include a certain amount of conversation about what new aches and pains you’ve developed. Thankfully in my case these have all been minor so far, the sedentary nature of my job being balanced by the fact that I never learned to drive and hike pretty much everywhere. My joints and spine are a little worn, but my heart and lungs are still fine.

And I am cautiously optimistic about the future. People in my family tend to die early or late. My mother was only fifty-four when she passed, my dad sixty-nine, but I’ve got aunts and uncles on both sides who lived into their nineties, so if I can make it another ten years without any major health issues popping up, I figure I’ve got a decent shot at making it another thirty. And dementia doesn’t seem to run in my family, so with a little more luck I should be able to keep writing right up until the end.

I will save the bucket list of Stories I Still Want to Tell for my next milestone birthday in 2035, except to note that I have a couple more Lovecraft Country novels that I intend to get to before I’m done. But my next published novel, which I just signed a contract for, will be something new and different. More details about that soon.

Anyway, happy birthday to me—and if you should find yourself in the Nordelta suburb of Buenos Aires today, please tell the capybaras I’m thinking of them.

August 1, 2025

I will be at Seattle Worldcon (8/13-8/17)

This year’s World Science Fiction Convention is being held in my hometown of Seattle, and the full programming schedule is now available on the con website, here.

Earlier this summer there was some controversy when it was revealed that the convention’s organizers had used ChatGPT to help screen prospective panelists. The good news is, I passed with flying colors. My list of events is as follows:

Thursday, Aug. 14, 1:30 PM, Room 345-346 — Reanimate This! — A panel about contemporary reinterpretations of Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos, featuring me, Evan J. Peterson, Nelly Geraldine Garcia-Rosas, Sadie Hartmann, and Usman T. Malik.

Thursday, Aug. 14, 3 PM, Room 435-436 — Realism as It Relates to Fear — A panel about the use and importance of realism in horror stories, featuring me, Gordon B. White, Clay Vermulm, MJ Kuhn, Nicholas Binge, and Usman T. Malik

Thursday, Aug. 14, 6-7 PM, Garden Lounge (3F) — An autograph session featuring me and ten other authors.

Saturday, Aug. 16, 1:30 PM, Room 433-434 — Your Book Became a Movie/Show. How Did It Go? — Panel about the joys of having your work adapted, featuring me, Luke Elliott, Caitlin Rozakis, Holly Black, Nicholas Binge, and Leigh Bardugo.

Saturday, Aug. 16, 3-4 PM, Dealer’s Room/The Book Bin — Signing books at the booth of Salem, Oregon’s The Book Bin.

I hope to see you there!

April 29, 2025

I’ll be at Seattle Crypticon this Saturday (5/3)

I will be appearing at Seattle Crypticon this weekend. The convention is being held, as usual, at the Doubletree by Hilton Hotel near SeaTac Airport (18740 International Blvd).

On Saturday, May 3, I’ll be on the “Writer’s Workshop: Bridging the Gap: Overcoming Writer’s Block and Idea Generation” panel at 1 PM, and the “Writer’s Workshop: Adaptations” panel at 2 PM, both of which are in Cascade 10.

Also, a quick heads-up that I will be at this year’s Worldcon in Seattle (August 13-17 at the Seattle Convention Center Summit Expansion). The panels haven’t been scheduled yet, but I’ll post my full itinerary on the appearances page as soon as they are.

January 27, 2025

The big South America trip, part five

Iguazú Falls (Brazilian side)

Iguazú Falls (Brazilian side)We cross back into Argentina from a place called Porto Mauá. There’s no bridge here, so we do it the old-fashioned way, by barge. Finding the Brazilian customs house and figuring out where to buy our barge ticket takes longer than the actual crossing.

On the far side of the river is Misiones Province, which of all the places we have visited so far comes closest to resembling the jungle of my mother’s stories. The one thing that disappointed me about Urwahnfried was that I didn’t see any scorpions, which were ubiquitous in Mom’s tales of her childhood, but if I were to beat the underbrush in the stretches of forest we are passing now, I bet I could find some.

We stop to take photos in a village called 25 de Mayo, where my grandmother lived for many years. Grandma was very unhappy in Buenos Aires; she missed the countryside, and grew so miserable that eventually Grandpa arranged to get her a plot of land up here. Like a German-Russian Henry David Thoreau, she went to live alone in a cabin in the woods while the kids remained with Grandpa in the big city.

I wonder aloud whether this is where Grandma decided to become a Mormon. Silvia says no, she’s pretty sure Grandma joined the LDS church after she moved to America. This surprises me—I’d always been under the impression that her conversion took place earlier. And with my brain already in story mode thanks to the landscape, the notion that it occurred here has a certain appeal.

I imagine a hot summer day in the 1960s. Two well-dressed young men, sweat staining the armpits of their white dress shirts, are forging a path through the nearby jungle. One uses a machete to break trail while the other clutches a mildewed copy of the text the angel Moroni supposedly revealed to Joseph Smith. They crash through a last stand of brush into a clearing. An assortment of dogs and cats and a one-horned cow all turn to look at these strangers, while chickens strut about unconcerned, and a mule hitched to a small wagon stamps its hooves impatiently. As the men approach the cabin at the clearing’s center, an old woman in a babushka emerges onto the front porch. She glares and brandishes the cane she uses to threaten unruly children, but the missionaries are undeterred; the one with the book steps forward. “Señora,” he says, “may we tell you about another testament of our Lord Jesus Christ?”

Yeah, OK, it probably didn’t happen that way. But a boy can fantasize.

Grandma doing a little light construction work on Long Island in the 1980s.

Grandma doing a little light construction work on Long Island in the 1980s.We continue driving north and reach Puerto Iguazú in the early afternoon. Like Niagara, Iguazú Falls straddles the border between two countries, with Brazil playing the role of Canada here (Paraguay is very close as well, and there are observation points where you can stand and see all three countries at once).

Each side of the falls has its own unique attractions. Today we visit the Brazilian side, whose cliffside trails offer panoramic vistas like this one:

When I’m not gawking at the view, I keep an eye out for wildlife, which Iguazú also has in abundance. I’m trying to get a picture of one of the big black hawks that keep swooping past us when a family of ring-tailed mammals emerge from the brush below the trail:

These are coatis. They seem completely unafraid of humans, though as with their American relatives, the raccoons, this should not be mistaken for friendliness. Signs posted throughout the park warn that coatis have sharp teeth and don’t like being petted. (You’re also not supposed to feed them, though I’m guessing the coatis’ own policy on snacks is more liberal.)

The next morning we check out Iguazú from the Argentinian side. Here you can get up close and personal with the falls, on elevated platforms built directly over the cataracts. The most impressive of these is ‘the Devil’s Throat,’ which you reach by following a long series of walkways across the upper rapids. You know you’re getting close when you see clouds of mist up ahead:

While I’m sure this view would be nightmare fuel to some folks, my biggest fear standing on this platform is that the iPad I’m using as a camera will get knocked out of my hands by one of the other tourists jockeying for position by the railing. Between the crowds and the windblown spray, you really need to take your selfies quickly here.

By mid-afternoon, we’re on the road again. It’s about a sixteen-hour drive back to Buenos Aires, but tonight we’re only going as far as Oberá, which should take only four hours. A traffic jam stretches the actual travel time to five hours and change, and when we finally arrive there are additional complications, like a noisy street festival being held in front of the hotel where we were hoping to sleep tonight. Once again I am thankful for my companions; though we are all exhausted, we treat it like a comedy of errors, greeting each new hurdle with a fresh round of jokes, and in the end we are rewarded with a good dinner and a good night’s rest.

We spend the entire next day on the road, except for a quick stop at Las Marías, a tea and maté plantation in Corrientes Province that is known for its resident population of capybaras. Alas, the woman in the gift shop tells us that we’ve come too early in the day; the capys are most active in the afternoon. I do manage to catch a passing glimpse of one submerged in a pond near the plantation’s entrance, but it’s clearly not interested in saying hello to me.

It’s after dark by the time we return to the house in Hurlingham, where Mika is overjoyed to see us. Karl’s flight home is in two days, so before going to bed we make plans to visit the city tomorrow.

The Obelisco de Buenos Aires, marking the spot where Colonel Sanders first raised the Argentine flag over the city in 1812.

The Obelisco de Buenos Aires, marking the spot where Colonel Sanders first raised the Argentine flag over the city in 1812.I like Buenos Aires a lot more than my grandmother did. My brain keeps trying to slap a New York vibe onto it, which doesn’t make a ton of sense at first, since architecturally the two cities don’t resemble each other: B.A., with more room to sprawl than Manhattan, has fewer and shorter skyscrapers, and none at all in the old city center. Part of it is my knowledge of my family’s history here, which gives me a feeling of belonging even as a first-time visitor. The snatches of overheard Spanish in the street also remind me of New York, as do, in a different way, the omnipresent burglar bars and the graffiti. Even the birds are familiar: instead of parrots or horneros, downtown Buenos Aires has pigeons.

Tony and Silvia do their best to show us the sights in the limited time we have. We take a guided tour of the Teatro Colón, where Grandpa used to go with my mother to see operas and musicals. We walk by the Pink House, where President Milei works, and visit the tomb of José de San Martín, the general who liberated Argentina, Chile, and Peru from the Spanish Empire. We cross the Avenida 9 de Julio, which according to Guinness is the widest avenue in the world.

Not all of the day’s highlights are on the official itinerary. We stop to get lunch at a restaurant just off the Avenida. As we’re going inside, a beautiful woman who seems way overdressed for this place brushes past me. We’re deciding what to order when music starts playing, and I see through the window that the woman is dancing around the outdoor tables with a guy I’d assumed was a waiter. So this is Buenos Aires, I think: You’re just minding your own business and suddenly a tango breaks out.

The next day, Karl’s last, we drive to a suburb called Nordelta. It’s a gated community, but they’ll let you in if you ask nicely, which we do. Nordelta sits beside a wetland. We drive slowly down a road between two huge ponds, scanning the edge of the water. I don’t see anything, but Tony’s eyes are sharper; he pulls the car over and points, and there they are: a pair of capybaras.

Capybaras, known as “carpinchos” in Argentina, are the largest rodents in the world. Their docile nature has made them internet famous, though as I quickly discover, wild capybaras are more skittish than the ones on YouTube, especially when their babies are nearby. But by crouching down and moving slowly, I’m able to get pretty close to them.

Tony calls out again; there are more capybaras on the other side of the road. A lot more:

I’ve still got two more days before I fly home, but for me, the real climax of the trip is here, standing on the banks of Nordelta with my cousins and these ridiculously oversized rodents. It’s like a scene from one of my mother’s stories—or, if we could figure out a way to work in a mule, one of my grandfather’s stories.

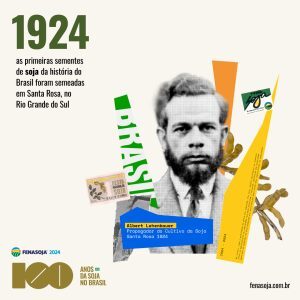

I’m so very happy that I made it here. And I’m grateful to everyone—Gerda Shiavoni, my family, the organizers of Fenasoja, and the people of Santa Rosa—who helped make it possible for me to finally see the place where my mother came from, and to learn a little more about Grandpa and the mark he left on the world.

I cannot say how much I am refreshed by a return into the full enjoyment of the manifold blessings of civilization during my stay in Germany and the United States… But there is no place just like Urwahnfried, and there is no substitute for the special blessing of God in the mission field.

— Albert Lehenbauer, “Roughing it for Christ in the Wilds of Brazil”

January 21, 2025

The big South America trip, part four

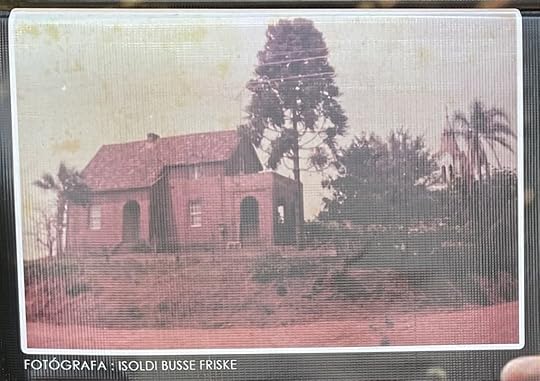

Detail from a banner showing a photograph of the old parsonage.

Detail from a banner showing a photograph of the old parsonage.The next day is the day I’ve been waiting for. We are going to the site of Grandpa’s old parsonage to attend a ceremony declaring it Ground Zero of the Brazilian soy industry. For me it is a more personal point of origin: the place where my mother was born. It is also the setting of many of her stories about her childhood, though this gets complicated, since in my mother’s tales, and perhaps in her own memory, the Brazilian and Argentinian wildernesses blend together to form one big fantastical jungle.

It is a place out of myth, and like all such places, it’s got a cool name. Grandpa called the parsonage Urwahnfried: “[It] is a word composed of old German word roots, and means in modern English, ‘Fulfillment.’ Or, more explicitly, ‘The Place where my Fight for the Highest and Broadest Ideals of Life Came to an End in the Peace of Victory.'” The same word was inscribed on his and Grandma’s wedding rings.

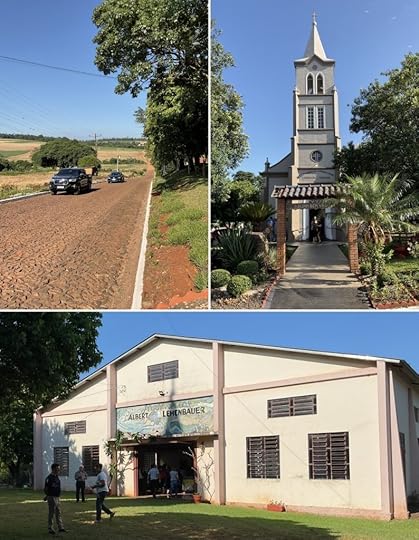

Márcio picks us up at the hotel early in the morning. It’s about a fifteen-mile drive, the last stretch along a dusty road paved with cobblestones. Most of Mom’s jungle is long gone, replaced by cultivated fields. The old parsonage is gone, too. In its place is a meeting hall where breakfast is waiting for us.

Urwahnfried today.

Urwahnfried today.As we eat, people continue to arrive. There are many reporters, and politicians eager to give speeches. When I step back outside, I spot a camera drone hovering overhead, a detail that strikes me as particularly surreal in this setting; I wonder what Mom’s five-year-old self would make of it.

Everyone gathers for the ceremony. After Cousin Walter gives the opening invocation, the rest of the family is invited up on stage. Karl and I are at the back, in front of a stand of flags, which becomes an issue when the wind picks up behind us. But the real problem is the sun; I’ve forgotten to wear my hat. I grab one of the billowing flags and on the pretext of holding it steady use it as a sunshield, which is disrespectful but preferable to skin cancer. This works until some well-intended soul yanks the flag out of my hand and ties it down to the flagpole. I scoot sideways into a narrow band of shadow cast by a tree bough. As the assembled dignitaries go on speaking, the sun and I continue to subtly shift position.

At last the Ground Zero plaque is unveiled, to much applause. Then it’s time for church. Karl hurries to get a good seat, but I take my time, as do Tony and Silvia; we’re all sweating in long pants, and it’s going to be even hotter inside.

It is a long service, conducted entirely in Portuguese. I stay through the end of Walter’s sermon, but when the regular pastor gets up to speak as well, I quietly slip out. I get coffee and leftover pound cake from the meeting hall and find a shady spot outside to sit. I survey the landscape and try to imagine what it was like here a century ago. I think about Mom.

My mother was an incurably restless person, and one of the ways that restlessness expressed itself was through driving, a trait I borrowed for the character of Hippolyta in Lovecraft Country. But where Hippolyta has the consolation of at least knowing what career she’d like to have, my mother didn’t even get that far. Though one of the smartest people I ever met, she spoke of being frustrated by the sense that she’d never found her true calling in life. She was always incredibly supportive of my own ambition to be a writer; the greater part of that was a mother’s love and the generosity she showed to everyone, but I think she also felt that if I’d been lucky enough to discover my life’s purpose, she was bound to do whatever she could to help me pursue it.

And she loved to drive. She was happiest when she was in motion, traveling to some other place that might be a little closer to whatever it was that she was looking for. She’d take any excuse to get behind the wheel and put another thousand miles on the odometer. Growing up, I spent a lot of time on the road with her, and when I started college, she drove me to and from Cornell every semester.

In my senior year, something happened; between the time she dropped me off in September and the time she picked me up in December, she appeared to age ten years—the result, I suspect, of some longstanding health problems finally catching up to her. I wasn’t entirely surprised, nine days into spring semester, when I learned that she was dead.

She had driven on her own to the vacation house she and Dad had bought in the Poconos. Like Urwahnfried, the Pocono house sat atop a low rise in the middle of the woods. It had been snowing, so she parked at the base of the driveway and started up to the house on foot, but before she reached it, her heart gave out. My father, who found her there, said that judging from the condition of the snow around her body, she made no attempt to get up after she fell, so she must have passed very quickly. And while some might be horrified by the thought of dying in the wilderness, to my mother, it would have been like going home again.

When my father died four years later, I was at his bedside, holding his hand. But Mom’s funeral was closed casket, so I never actually saw her dead. From my perspective, it’s always been as if, after dropping me off at school that last time, she got back on the road and just kept driving. There have been times in my life since when I’ve had things I wished I could share with her, and I have pictured her out there, still behind the wheel somewhere. Still searching.

And this is the point where, if I were describing my visit to Urwahnfried in a novel, I would be tempted to include some ambiguously supernatural occurrence, some sign that my mother really is still out there. In reality, no such thing happens. I know the reason why, and it’s got nothing to do with the Lutheran doctrine that ghosts don’t exist. My mother’s spirit does not appear because it’s already here, in the form of me still thinking about her thirty-seven years after I watched her drive away for the last time. And years from now, even after my own memory fails, the consequences of her life, like the consequences of my grandfather’s life, will persist and endure.

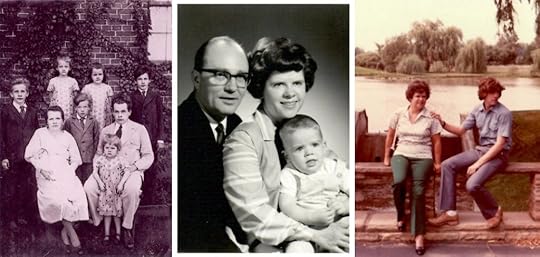

From left: Mom (the blond toddler) with her family in 1936; Mom with Dad and me in 1966; Mom with me and my big hair in 1981

From left: Mom (the blond toddler) with her family in 1936; Mom with Dad and me in 1966; Mom with me and my big hair in 1981• • •

Another day, another honor for Grandpa: the main thoroughfare at the Santa Rosa fairground is being renamed the Rua Pastor Albert Lehenbauer.

It’s the second time he’s been commemorated in this way. There’s another Rua Pastor Lehenbauer closer to the city center; Márcio was kind enough to take us there earlier. Karl and I had already known from Google Street View that the old Rua Lehenbauer wasn’t particularly impressive—it’s a little three-block residential strip—but when we got there we were surprised to discover that all the street signs were misspelled, and in different ways: “Rua Pastor Lemembauer,” “Rua Pastor Lehembawer,” etc. I should stress that no one was upset by this, in fact Karl and I thought it was pretty funny, but of course the first thing we do when we arrive at the fairgrounds is check the spelling on the new signs. Good news: they got it right this time.

How it started / How it’s going

How it started / How it’s goingFour of the fairgrounds’ cross streets are also being renamed, in honor of four of Grandpa’s parishioners who were important early contributors to the spread of soy cultivation in the region: Gustavo Bessel, Emanuel Brachmann, Johan Müller, and Bruno Schwartz. Their descendants are here to celebrate as well. We board electric carts and get driven around from intersection to intersection, so everybody gets a chance to take selfies with their ancestor’s street sign.

Then it’s on to the festival hall, where each of the five families will be called up in turn to receive a special plaque, along with other gifts. But first we are treated to a musical extravaganza. A boy playing Grandpa is joined by a group of singing and dancing young women in brown skirts and lamé tops. I start laughing as I realize that these women are the soybeans. (There are also four black cubes that get picked up and moved around during the dance numbers. Do these represent the Bessel, Brachmann, Müller, and Schwartz families? Maybe. Or maybe I’m overthinking it.)

I can’t say what Grandpa would make of this, but I find the whole thing delightful. There’s a point during the third or fourth number where I flash back on the last live musical I saw—Hamilton—and burst out laughing again. Lin-Manuel Miranda was right: Immigrants get the job done.

Before we know it, our time in Santa Rosa is over. On the morning of December 4, we join the other cousins for a farewell breakfast in the hotel restaurant. We share a few more family stories and joke about coming back for the bicentennial. We take our time saying goodbye.

Everybody else is headed home now, but Tony, Silvia, Karl, and I have a sidetrip planned before we return to Buenos Aires. We get in the car and drive north, to Iguazú Falls.

From left: Brigida (our Fenasoja coordinator), Ruth, Walter, Norma, Silvia, Tony,

From left: Brigida (our Fenasoja coordinator), Ruth, Walter, Norma, Silvia, Tony,Janis, Karl, Carolyn, me, Ingrid, Lia, Vera, and Lisete Friske.

January 18, 2025

The big South America trip, part three

Karl, me, Silvia, and Tony. Behind us is the Uruguay River, which forms part of the border between Argentina and Brazil.

Karl, me, Silvia, and Tony. Behind us is the Uruguay River, which forms part of the border between Argentina and Brazil.A few words about my travel companions.

Karl is the son of Freddy, my mother’s youngest brother and the only one of her siblings to be born in Argentina. Freddy came to the U.S. around the same time Mom did. Karl and I knew each other as kids, but since Mom’s death we’ve only seen each other a couple of times—once at Freddy’s funeral, and more recently at our aunt Elisabeth’s ninetieth birthday party.

Tony is the son of Aunt Flora, the woman who, while staying at our house in the 1970s, taught me how to touch type. I got to know Tony and his wife, Silvia, when they were visiting my cousin Norbert (one of Aunt Naomi’s kids) on Long Island in the 1990s; we got along well back then, but people change, and Silvia will later confess she was worried that after thirty years, we might not like each other anymore.

But we do like each other, a lot. We are an amiable group, the missionary zeal that runs in the family being tempered by an easygoing irreverence. Maybe it’s the Argentine influence—or in my case, the Ruff influence. We all have our opinions, but we know how to distinguish between the few beliefs that matter and the many that don’t, and we don’t take ourselves too seriously. By the time we return to Buenos Aires, we will have driven nearly eighteen hundred miles together without ever once raising our voices in argument. For Lehenbauers, this is a feat akin to walking on water. I end up being very glad that I accepted Silvia’s invitation.

About 50 miles from Buenos Aires, just outside Zárate.

About 50 miles from Buenos Aires, just outside Zárate.The first day, we’re on the road by 7 AM. At our breakfast rest stop, Silvia introduces me to the medialuna, Argentina’s version of the croissant, which is smaller than its French cousin and commonly glazed with sugar.

I’m still licking my fingers as we come to first of the many police checkpoints we will encounter on our journey. It looks like the cops have set up a used car lot by the side of the highway. They run Tony’s license and registration before waving us on, and I realize the “used cars” belonged to people whose I.D. didn’t pass muster. Thinking of the burglar bars on the house in Hurlingham, I assume that this has something to do with cracking down on car theft. But Tony explains, in the deadpan way he has, that the reason for the checkpoints is that the police are bored and don’t have enough to do.

It doesn’t take long for us to think of some things they could be doing. The highway is in bad shape; Tony is constantly swerving around potholes, and adding to the obstacle course are many uncollected strips of rubber shed by the retread tires of long-haul trucks. At one point, traffic slows to let a pair of skinny dogs cross the road, but elsewhere we see the corpses of animals that weren’t so lucky. Among these is a creature I take to be a javelina or a wild pig, but which Silvia informs me was a capybara—the first one I have ever seen in the wild. I’m glad I didn’t get a better look at it.

There are also many tollgates, which sparks a joking discussion about what, exactly, the toll money is being spent on. Tony suggests that it goes to pay for the superfluous warning signs marking the worst stretches of unrepaired highway; this becomes a running gag, which Karl and I proceed to drive into the ground. Silvia meanwhile insists we’re looking at it backwards. You need to imagine what the road would be like without the tolls, she says.

For all our good-natured complaining, we know how lucky we are, traveling sixty miles an hour in air-conditioned comfort with only an occasional thrashing of the axles. In Grandpa’s day, not only was there no A/C, there wasn’t even, in the most literal sense, any horsepower, the terrain in Guarany being so rough that he took to riding mules instead:

On another occasion I had bought a number of maps for my schools at Ijuhy. To make sure that they would reach home in a dry state, I wrapped them up in my raincoat and sent them on with a driver. It was a fine, sunny day in winter. I intended to take a round-about way, raising the distance to 20 hours. But I meant to ride this distance without a stop, keeping at it all night, in order not to miss the hour of catechism instruction at home. Towards evening it began to drizzle, and the darker it got, the harder it rained, and the harder it rained, the colder it got. And poor me with only a khaki riding suit! At about seven o’clock we, meaning myself and the mule, fell into a ditch. I have always maintained that this was intentional on the part of the mule. But I did not want to risk it again. By the momentary illumination of a streak of lightning I picked out a thorn bush under which to seek shelter. Not that it was raining less fiercely there, but still there is a certain feeling of protection under a bush, in the midst of the wide plain in rain and lightning and thunder. In order not to tire, I stood first on my eastern leg and then changed about to the western one. The mule did about the same. After nearly twelve hours of this changing about the morning dawned, and the rain abated and finally stopped. The warm sun went to work on my wet clothes, and when after ten more hours in the saddle I reached home, I had no need to fear a scolding for having gotten my nice clothes wet. I even found a long rod of iron on the road, picked it up and returned it to the driver who had lost it, making him very happy.

— Albert Lehenbauer, “Roughing it for Christ in the Wilds of Brazil”

Google Street View image showing a typical roadside scene in Argentina’s Corrientes Province.

Google Street View image showing a typical roadside scene in Argentina’s Corrientes Province.The uniform line of trees in the distance are eucalyptus being grown for timber.

By late afternoon we are in Santo Tomé. We have reservations for the night at the Condado Hotel. When I get to my room I find a slot on the wall, just inside the door, where I have to insert my keycard to turn on the power. This is an energy-saving feature that prevents guests from running the A/C all day while they’re out. It’s a clever idea, and Tony predicts that it will eventually be adopted by American hotels as well, though he notes there are still some kinks to be resolved: removing the keycard turns off all the power, including the socket for the mini-fridge, and of course you can’t leave your devices in the room to charge.

We have dinner in the hotel’s casino, a banquet hall with rows of slot machines. Due to hyperinflation, the Argentine peso is currently trading at a thousand-to-one against the American dollar, which combined with the fact that the peso is denoted by a dollar sign makes for some crazy-looking menu prices. I have a $14,000 steak with fries and a $3,000 bottle of Sprite. Karl orders a $25,000 bottle of wine. The full price of dinner for the four of us comes to $88,000, which Karl insists on paying. He’s being generous, but he’s also hoping that the unconverted peso figure will show up on his credit card bill where his wife will see it.

Santo Tomé is a border town; the next morning we drive to a bridge that crosses the Uruguay River into Brazil. The new visa requirement for American tourists has been postponed until 2025, so all I have to do is fill out a digital form and show my passport. Ten minutes later we’re in the old country.

The landscape on the far side of the river is very similar—farmland with scattered patches of forest—but I notice the Brazilians are growing a different mix of crops, including the soybeans that are Grandpa’s legacy. The highway is in better shape, but the paucity of road signs triggers another round of toll-related jokes. It’s OK, we’ve got GPS to find our way.

We reach Santa Rosa at around 1 PM and drive to the Imigrantes Hotel, our home for the next four nights. Cousins Ingrid and Norma are waiting to greet us (along with Walter, Lia, and Vera, they are the children of Uncle Siegfried, Mom’s eldest sibling). Our rooms aren’t ready yet, but Fenasoja’s organizers have arranged a lunch for us at the fairgrounds, and they’ve also assigned us a minibus for the duration of our stay. Our driver is a very friendly guy named Márcio; later he will ask to take a photo with us, to prove to his family that he was the Lehenbauers’ chauffeur.

We meet up with the other cousins at the fair. Cousin Walter is a big star; his work helping Fenasoja prepare for the centennial has made him the public face of the family, and he’s constantly being pulled aside to do interviews. Lia and Vera are there as well, along with Walter’s wife, Ruth, and Janis and Carolyn, granddaughters of Grandpa’s sister Katharina, whose family now own the West Ely farm.

After lunch we have a brief look around the fairgrounds. Among other things, Fenasoja is a tech expo, with a whole section devoted to the latest farm equipment, everything from drones and tractors up to house-sized harvesters (if you’ve ever wanted to sit in the cockpit of one of those things, you can, though you’ll have to wait your turn behind a line of little kids). They’ve got farm animals too, and amusement park rides, an open-air concert arena, and crafts pavilions offering the expected (leather goods, jewelry, organic preserves) and the unexpected (Brazilian timeshares). I feel sorry for the people trying to sell clothing, especially handknit stuff. When they paid for their booths, they thought Fenasoja would be taking place in May—late autumn—but the six-month delay caused by the floods means it is now the beginning of summer, and with the temperature in the nineties and humidity at seventy percent, nobody is looking to add layers.

It’s a relief to get back to the air-conditioned hotel. We check in, and after a quick shower, I join my cousins for coffee and cake with a woman named Lisete Friske. Ms. Friske is a historian whose research helped make the official case for Grandpa’s foundational role in the Brazilian soy industry.

It turns out that Grandpa did not literally bring the first soybeans to Brazil (though he does get credit for introducing the Common Yellow cultivar, the variety of soy he transported in his bottle). The earliest record of Brazilian soy cultivation was in Bahia at the end of the 19th century. But previous attempts to commercialize soy didn’t go anywhere. Ironically, part of the reason Grandpa’s efforts had such an impact was that he wasn’t worried about profit; he just wanted to make people’s lives better. And crucially, he was a pastor, at a time when the pastor’s word was law. He didn’t have to answer to investors or provide any sort of practical timetable for when his soybean scheme might start to pay off. He just told people to try planting soy and they did, even if they had no earthly idea what it was good for.

This makes sense to me. I remember when I was a kid, the way strangers talking to my Dad would turn instantly deferential when they found out he was a preacher. And that was in the 1960s and ’70s, when the cultural force of organized religion was waning in America. The ability of a pastor to command respect and obedience in rural Brazil in the 1920s would have been much greater. I am glad Grandpa used his power for good—and that his soybean scheme actually did pay off.

Pizza night with the Lehenbauers and the Priebes

Pizza night with the Lehenbauers and the PriebesIn the evening, Márcio drives us into town to a restaurant called Pizzaria Veneza, which is like a dim sum house for Italian flatbread. Waiters circulate with a seemingly endless variety of thin-wedged pizza slices; some of the more exotic toppings include figs, chicken hearts, and Doritos. (There are dessert pizzas too, topped with berries and chocolate, but by the time these make an appearance I’ll already be stuffed.)

We are joined by some of Grandma’s people, the Priebes. Unfortunately, the language barrier prevents me from really connecting with any of them, but through Cousin Walter, I try to get an answer to a question Karl and I have been debating: Where exactly was Grandma born? According to the Lehenbauer Book, the pre-Ancestry.com genealogy of the family, Helene Priebe’s birthplace was “Lubatscheck, Russia,” but if you search for Lubatscheck on Google, the only hit you get is from an online scan of the Lehenbauer Book.

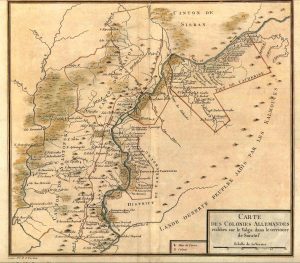

1788 map of Volga German settlements

1788 map of Volga German settlementsby Pierre Francois Tardieu

[click to enlarge]

Walter says that nobody really knows the answer. Lubatscheck may well have existed at one time; it wouldn’t be the first Russian village to have vanished without a trace. We do know that the Priebes were Volga Germans, German immigrants invited by Catherine the Great to settle and cultivate the steppes around the lower Volga River. So Grandma’s birthplace would have been somewhere in that general area.

The Priebes left Russia just a few years before the outbreak of World War I. Whether that was luck or foresight, Walter can’t say, but he can tell me why they decided to emigrate to Brazil. At the time, immigration officials in the U.S. had a reputation for being very picky about who they let in and who they didn’t; the smallest thing might get you bounced back to Europe. Brazil was known to be far less discriminating. So rather than take their chances at Ellis Island, the Priebes chose to go to Guarany, in the process making it possible for Grandma and Grandpa to meet. I owe my existence to America’s illiberal immigration policy.

On the way back to the hotel, Cousins Lia and Vera share another immigration story. When they first came to the U.S., they lived with Walter in Arkansas, where he was serving as a pastor. Later they moved to New Jersey. When they went to get new driver’s licenses, the woman at the Jersey DMV insisted that there was no such place as Arkansas. As Lia and Vera would know if they were American, the real state was called Kansas; their old licenses were obvious forgeries. Being Lehenbauers, Lia and Vera stood their ground, and the situation escalated until another DMV employee came over and confirmed that Arkansas existed. He knew this because the president was from there.

So thanks to Bill Clinton, Lia and Vera got their New Jersey driver’s licenses.

January 17, 2025

The big South America trip, part two

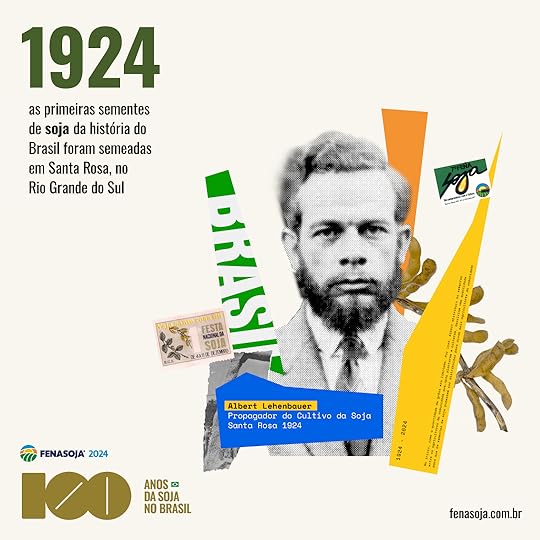

Now that I’ve decided to attend Fenasoja, I have to figure out how to get there. Travel has gotten a lot faster since Grandpa’s day, but Guarany is still relatively remote. To reach Porto Alegre from Seattle takes a minimum of three plane flights, and from there I’ll either need to get on a small commuter plane that only flies every other day, or take a nine-hour bus ride.

I jump on the Lehenbauer mailing list to ask if there are any other options I’ve missed. I also mention that as long as I’m coming all the way south, I’d like to work in at least one side trip, to either Brasilia or Buenos Aires. Does anyone have any thoughts on that?

One of my Argentine cousins, Silvia, replies that she and her husband Tony are planning to drive to Fenasoja from their home in Buenos Aires. I’m welcome to ride along with them, and if I do, I can spend some time exploring B.A. either before or after the festival. I immediately say yes—in addition to simplifying things, a road trip with family sounds a lot more fun than wandering around Brazil on my own.

I book my plane ticket and get to work on travel permissions. To enter Argentina all I need is my passport; this used to be true of Brazil as well, but starting in April of 2024, American citizens will require a tourist visa. This raises the question of whether I should claim Brazilian citizenship, which I’m entitled to do since my mother was born there. The idea of having a second passport is intriguing, and Brazil’s is one of the best in the world, but without talking to a lawyer about possible downsides—like tax liability—I’m reluctant to open that door for the sake of a five-day visit. For now, I decide to stick to being American. I go online, pay a small fee, and within a week I’ve got a downloadable evisa that’s good for ten years.

Next up, vaccinations. The CDC’s specific recommendations for travel in Rio Grande do Sul include hepatitis A and B, measles, typhoid, and yellow fever. That last one is a bit spicy: the yellow fever vaccine is a “live” vaccine, meaning it uses a weakened version of the actual hemorrhagic virus that causes the disease. As long as you’re not immunocompromised or a member of the Kennedy family, it’s considered low-risk, but the list of potential side effects is eye-opening. The doctor who gives me the jab tells me that fever and chills are a common reaction to the vaccine, and “vomiting is OK too,” but if I experience numbness or any other neurological symptoms I’ll want to get to a hospital as soon as possible. Fortunately, a lifetime of sanitary practices like picking up and eating food off the floor has given me the immune system of a junkyard dog; I don’t even get the fever and chills. Thanks, five-second rule!

By the time I’m fully vaxxed, it’s almost time to go. I’m due to fly on May 16. But on the 7th, Silvia gets in touch with bad news. There’s been massive flooding in Rio Grande do Sul. Though the floods have spared Santa Rosa, where Fenasoja is held, much of Porto Alegre is underwater, and with the state’s main travel hub shut down, the festival will have to be postponed. We say our prayers for the people affected and start making new plans. Fenasoja is rescheduled for late November/early December. I rebook my flight for the day before Thanksgiving.

The months pass quickly. There are no further acts of God, but Delta keeps things interesting by rescheduling my flight several times. By Thanksgiving week, my original 7:20 AM departure has been changed to 6 AM, which means I’ve got be up at 2:30.

I wake before the alarm goes off, triple-check that I’ve got everything, kiss Lisa goodbye, and head out the door. Everything goes smoothly until I reach the airport.

It’s been a long while since I’ve a checked a bag for a flight, and 3 AM on minimal sleep is not the best time to be remembering how to do that. I print out my baggage tag at a kiosk and proceed to overthink the simple instructions for how to attach it. I get so focused on this that I forget I’ve got a carry-on bag, too. Fortunately, the baggage thieves and bomb-sniffing dogs are all still in bed, so when I come running back to the kiosk in a panic fifteen minutes later, my carry-on is still there.

Up in the air, the excitement continues: about an hour out of Seattle, a flight attendant gets on the intercom to ask if there are any doctors on board. I look around and see that a guy in an aisle seat a couple rows behind me is slumped unconscious. From what I overhear, it sounds like he’s having a heart attack. I check the inflight map and try to work out where the emergency landing will be. But the plane keeps flying, and after a couple army medics give him oxygen, the passenger revives. Soon enough he’s sitting up with a sheepish look on his face. I guess he just forgot to take his blood pressure medication.

I spend my seven-hour layover in Atlanta exploring the airport’s many terminals, taking care not to lose sight of my carry-on again. Shortly before my connecting flight to Buenos Aires is due to board, an alarm sounds, and a recorded voice announces, over and over, that an emergency has been declared. The airport employees strolling through the concourse don’t seem very concerned, so I conclude that this is probably just a drill. Nothing explodes or catches on fire, and after about five minutes, the alarm shuts off.

The flight boards on time and soon we are airborne. I’ve got the collected works of Julio Cortázar on my iPad, and I was thinking I’d read Hopscotch on the way down to Argentina, but it turns out the inflight entertainment system has got the entire John Wick series available to stream. So much for literature. I watch Keanu Reeves kill people for a few hours and drift off somewhere over the Caribbean. Then around 4 AM, give or take a time zone, someone starts screaming for help. It’s another medical crisis, this one involving a woman who’s had a stroke. Except that she hasn’t. After a brief flurry of activity, we’re told that “she’s fine” and everyone goes back to sleep.

We land in Buenos Aires without further incident.

Tony and Silvia are waiting in the terminal, along with my cousin Karl, who’s just arrived from Nashville. It’s been a long time since we’ve seen each other—decades, in Tony and Silvia’s case—so we all stare for a moment, making sure we’ve got the right old people.

Tony and Silvia live in Hurlingham, a suburb about forty-five minutes’ drive from downtown Bueno Aires. Like most of the other buildings in the area, their house is heavily fortified, with bars on the windows and a metal gate over the front door. Burglary is a big problem here, Silvia explains.

Inside, the house is lovely. It’s actually two houses, the main house in front and a separate guest house in back, where Tony and Silvia’s daughter Stefanie lives with her husband. Sandwiched between the two dwellings is a beautiful walled garden that I instantly covet. The garden is the domain of Mika (pronounced Micah, like the prophet), a very sweet Labrador who becomes my new best friend.

It’s about ten-thirty in the morning now, so after Karl and I wash up, we go out to breakfast at Lo de Carlitos, a restaurant chain whose specialty is “panqueques,” Argentine crepes piled with sweet or savory toppings. I go for one with chicken, cheese, roast vegetables, and a fried egg on top, which is delicious.

We have dessert at an ice cream parlor down the block, then head over to Concordia, the seminary that Grandpa founded in the 1940s. We visit his old office, the chapel, and the library that was, of course, his favorite room in the building. All of this is cool, but if I’m honest, it’s the wildlife that makes the biggest impression on me. Out on the grounds, I see parrots flitting between the trees. Tony tells me the parrots aren’t true natives; like their cousins on Telegraph Hill in San Francisco, they are escaped pets who became naturalized.

The native birds are down on the ground, pecking at the dirt: horneros, who use mud to build hut-shaped nests in the crooks of trees or atop utility poles. Once you know what the nests look like, you see them everywhere.

Seminario Concordia

Seminario ConcordiaFrom Concordia we drive to San Martín Cemetery, where Grandpa’s ashes are interred. Tony says that Grandpa could have chosen to be buried at the old parish in Brazil, but speculates that he opted for cremation here instead in order to avoid having his gravesite become a shrine. This seems a wild notion at first, but when I get to Santa Rosa and see how Grandpa is still revered there it makes a lot of sense.

We find Grandpa’s niche in an alcove on the top tier of the columbarium. The alcove is rather gloomy and run down, but it’s got a nice view of the cemetery below. Not that Grandpa would have cared. Lutheran doctrine is clear: the souls of the departed do not remain on earth, and they certainly don’t haunt graveyards. But we pay our respects just the same.

Then we head back to the house. After an early dinner, we all turn in. We’ve got a long drive tomorrow.

January 16, 2025

The big South America trip, part one

The story of my recent trip to South America to attend the Fenasoja Festival actually begins more than a century ago, in 1915, when my grandfather, the Lutheran missionary Albert Lehenbauer, accepts a call to the southernmost state of Brazil.

He leaves his home in West Ely, Missouri and takes ship for Porto Alegre. During a port stop in the state of São Paulo he is nearly left behind when his steamer sails ahead of schedule. To avoid being stranded, he’s forced to hire a rowboat to chase after the big ship. They manage to catch it, but the incident leaves him with no money to buy food for the rest of the voyage.

He arrives in Porto Alegre thinner but wiser. After a couple days’ rest at the local seminary, he heads into the interior, traveling by railroad and horse buggy to his new parish.

Guarany is its name, and by an unconscionable oversight of the mapmakers it is not to be found on most maps… Pronounce it “gwah-rah-nee,” with a strong accent on the last syllable. This final “y” in so many South American words is an Indian word for “water” or “river.” But Guarany is at present not the name of a river, but that of a large colonization conducted by the State Government of Rio Grande do Sul. Of this large colony I was interested only in a small part, which is settled almost exclusively by German Russians. Try to imagine a huge piece of crumb cake about 15 miles long and 7 miles wide. The crumb part of the cake is pure, unbroken Brazilian forest primeval, consisting of trees with crooked trunks and a dense undergrowth of vines, shrubbery, bamboo, ferns, etc. Now imagine yourself cutting this cake lengthwise into strips 1.2 miles wide. I am sorry to burden your mind with these fractions, but they are caused by the fact that the metric system of weights and measures is used by the Brazilian government. I wish it were so in the United States, too. Where the knife has passed in cutting the cake we shall imagine bridle paths, in places even closed at the top by the dense branches of the trees and the vines growing on them. Later on these paths will be widened out into wagon and automobile roads, and a few of the most important ones could be used for wagon traffic when I arrived. Now, please, one cut across the middle of the cake, converting each long strip into two shorter ones. This is our only crossroad, and a poor one at that, as most of the stumps seem to have chosen their places in the road and not beside it, and the one gutter or drainage ditch runs exactly down the center of the road. Now and then you meet a mud hole at the sight of which you feel uncertain whether to walk, swim, jump, or fly. As recently as 1921 I know of a case where the horse of an immigrant suddenly and completely disappeared in such a hole and was barely saved from drowning. Your uncertainty is, however, not the hole’s fault, but is due to your inexperience. You are still a greenhorn in matters of Brazilian roads. You’ll learn soon.

— Albert Lehenbauer, “Roughing it for Christ in the Wilds of Brazil”

State of Rio Grande do Sul, circa 1915. The X marks the approximate location of Guarany.

State of Rio Grande do Sul, circa 1915. The X marks the approximate location of Guarany.He lives at first in an old millhouse, with the miller serving as his mentor. “I learnt to understand and to speak the particular brand of German that these people use; I became thoroughly acquainted with the good and bad sides of their characters, I learnt to see the good kernel under the rough shell, whenever there was one; I became thoroughly conversant with the tricks and arguments used by the various enemies of true Lutheranism, and had some powerful weapons against them put into my hands by that ‘old’ miller-theologian; I underwent a thorough postgraduate course in the application of our Lutheran doctrine to the special new conditions that were confronting me in my work.” After months of instruction, he earns his missionary diploma “after a debate with a chief enemy that lasted from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. without so much as an intermission to drink a glass of water.”

Now the real work begins. He rides a circuit between seventeen different mission posts, spending as much as twenty hours in the saddle at a stretch. At home, in the newly-built parsonage, he meets regularly with a group of “progressive young men” and makes plans to improve the material as well as the spiritual conditions in the colony. They do what they can to consolidate the scattered congregations; they also reform the local postal service, organize schools and enlist volunteers to teach in them, and create a circulating library to further increase literacy.

In 1918, Grandpa marries one of his congregants, a young woman named Helene Priebe. “She is a German Russian by birth, a Brazilian by adoption since her eleventh year, and American by sympathies and by marriage. Having had no school, she is a wonderful reader. In her confirmation days and after, she memorized all of the synodical catechism, including most of Luther’s introduction. In her girlhood days she made 14 miles afoot and back on the same day, in the rain and barefoot, of course, to hear one of our chorus concerts. As a mother, she is one of the most up-to-date scientific child raisers I know of.”

They will go on to have eight children, all of whom survive to adulthood. My mother, Monica, born in 1932, is the sixth child and the youngest of three daughters. But that’s getting ahead of the story.

In 1923, Grandpa takes a sabbatical, traveling with Grandma and little Uncle Siegfried to Germany and the United States. At the old farm in West Ely, he collects some soybeans to bring back to Brazil, as part of another plan to improve life in Guarany. This is the single most consequential thing he will ever do, but he almost abandons the plan out of concern that the beans will spoil on the long boat ride through the tropics. It’s Grandma who saves the day by telling him to pack the soybeans in a sealed glass bottle.

Her suggestion works. The beans survive the trip and germinate successfully in Grandpa’s test plot back in Guarany. He takes a portion of the crop and distributes it to a group of his parishioners, instructing them to reserve a portion of their first harvest to share as well. The beans adapt well to the local soil and the yield is phenomenal, so there’s plenty to share. The only trouble is, nobody knows what to do with the soybeans they don’t give away. At this point in Rio Grande do Sul’s history, Japanese restaurants are thin on the ground, and the local gauchos have yet to discover the joys of tofu and edamame.

They do like pork, though. And it turns out that if you feed soybeans to pigs, they get very fat very fast and have lots of babies. Soon the people of Guarany have more pigs than they know what to do with, and this, along with the continued expansion of soybean farming and related industries, begins to transform the local economy.

Grandpa and Grandma remain in Brazil for another decade and a half. In 1938, Grandpa receives a new call, to a school in Argentina. The family packs up and moves to Crespo in the province of Entre Ríos. In 1941 they move again, to Buenos Aires, where Grandpa embarks on his last great work, the founding of Concordia Seminary. In 1955, Grandpa attends a pastoral conference in Paraná. On his way back to Buenos Aires, he suffers a stroke. He’s taken off the train in Zárate and dies in the hospital there.

My mother emigrates to the United States. Eventually she meets a hospital chaplain named Jack Ruff. They marry in 1964 and I’m born a year later. Our house in Queens becomes the first stop for other South American relatives coming to the U.S.

In 1970, Grandma moves in with us. In the years since Grandpa’s death, she has converted to Mormonism. My mother knows better than to fight against this, but some of our other house guests can’t help themselves; often their first act after putting their luggage down is to grab a Bible and try to argue Grandma back to the True Faith. Their efforts are in vain; she will die a Latter Day Saint.

Growing up in this multicultural theological debate society has a profound effect on my later career as a novelist. Long before “diversity” becomes a progressive buzzword, I learn that I will be spending my time on this planet surrounded by people who do not share my worldview and cannot be magically converted to my way of thinking, but who I nevertheless need to find a way to get along with. The good news is that it’s actually not that hard to understand people who are different from you; it’s mostly a matter of practice, and I get a lot of practice. Years from now, when puzzled interviewers ask me how a white guy managed to write Lovecraft Country, I will tell them I have my family to thank.

In 1982, my parents take a trip to Brazil and Argentina. I have school so I can’t go with them. Later I will regret this, but at the time I’m all too happy to be left unchaperoned for several weeks. I tell myself that there will be other opportunities to tour South America with my folks. Unfortunately, this isn’t true. My mother dies in 1987, during my last semester of college, and Dad dies four years later. The South America trip goes on that list of things I intend to do eventually, but never quite get around to.

Fast forward several decades, to the amazing future year of 2022. My cousin Walter posts a message to the Lehenbauer mailing list. Soon it will be the hundredth anniversary of Grandpa bringing soybeans to Brazil. There are plans to celebrate the centennial at the 2024 Fenasoja festival in Santa Rosa, and as Grandpa’s descendants, we are all invited to attend as honored guests.

If I’m ever going to make that South America trip, this is my chance. And if the Lovecraft Country HBO series were still on the air, it would be a no-brainer. But the show only got one season, and while Lisa and I still have plenty of savings, I am at one of those points in the feast-or-famine cycle of my career where I have to think carefully before spending several thousand dollars. I tell myself I’ve got two years to decide, but before I turn around it’s late 2023 and my cousin Lia posts a reminder that Fenasoja is coming up fast. Thousands of people will be attending the festival and hotel space in Santa Rosa is limited, so anyone who wants to come should book now.

I’m still trying to make up my mind when out of the blue I get another email. It’s from Gerda Shiavoni, a former coworker of my mother’s and a very old friend of the family—I was the ringbearer at Gerda’s wedding when I was just seven years old. Gerda is in her eighties now, and she’s emailing to ask for my address. She’s got something she wants to send me, as a thank you for the kindness my parents showed her when she first came to America. The something turns out to be a check in almost the exact amount I need to cover my travel expenses to Fenasoja.

I know a sign when I see one. I call Gerda on the phone to say thanks and to let her know that the timing of her gift could not have been better. Then I start making travel plans.

January 1, 2025

Hello, 2025

Wow, a quarter of the new century gone already. How did that happen?

Judging by my social media feeds, a lot of people are glad to put 2024 behind them. But to me, it will always be the year I finally got to see the place where my mother was born. My trip to Brazil and Argentina was as wonderful as I hoped it would be, and I’ll be posting a report of my adventures among the gauchos and capybaras in the next few days.

As for the frequently asked question, “What are you working on? Another Lovecraft Country sequel? A different novel? Some other creative project?” the answer is, “All of the above.” My chief new year’s resolution is to figure out which of the many irons I’ve got in the fire to prioritize. But there are worse problems for an artist to have, and as I contemplate turning sixty this September, it’s a comfort to know that while I can’t help getting old, I’ve still got more ideas than I know what to do with.

November 13, 2024

Back to the old country

In two weeks I will be on my way to South America.

My maternal grandfather, the Lutheran missionary Albert Lehenbauer, was the man who brought the first soybeans to Brazil. This year is the hundredth anniversary of that event, and Grandpa is being honored at the Fenasoja soybean festival in Santa Rosa, Rio Grande do Sul.

I’ve never been to Brazil before, and I figured if I was ever going to visit the place where my mother was born, this was the time to do it. Because of the centennial, many of the surviving Lehenbauers will be there, as well as a number of my grandmother’s people, the Priebes, so I’m sure I’ll hear lots of great stories about the old days.

Even in the twenty-first century, Santa Rosa remains a remote location. To travel there by air from Seattle requires a minimum of four flights: three to reach the state capital of Porto Alegre, and then a hop to the interior on a commuter plane that only operates three times a week. Fortunately, my Argentine cousins Silvia and Tony are also planning to attend, and they invited me to tag along with them, so what I’m actually going to do is fly to Buenos Aires, embark on an epic 700-mile road trip to southern Brazil, and then, after the festival, return to Argentina and spend some more time exploring B.A. before I head home.

I’ve been anticipating this trip for more than a year, and it’s hard to believe that it’s almost here. All the important preparations were taken care of months ago, and now I’m down to making sure I haven’t forgotten anything and compiling a wish list of stuff I want to see while I’m there.

People who know me will not be surprised to learn that the list includes wildlife. Capybaras are native to the region, and I am going to do my best to meet one, or a dozen (in 2020, an army of capybaras invaded the Nordelta suburb of Buenos Aires, but alas, Silvia tells me they’ve since been relocated).

I’ll be taking lots of pictures and posting them to my Twitter feed (whether this happens during the trip or after will depend on the wifi situation and Elon Musk’s relationship status with the governments of Brazil and Argentina). And there’ll be a detailed trip report here on the blog when I get home. Stay tuned.