Arlene Miller's Blog, page 67

September 21, 2013

National Punctuation Day

Punctuation Rules!

September 24th is National Punctuation Day. It seems right that we should pay homage to punctuation in this blog post……

How? Well, I will briefly go through the common punctuation marks and when to use them….and then the best part will be at the end. Here goes:

Period: (.) Use at the end of a sentence. Also use in some abbreviations. Not generally used in acronyms that are capitalized such as IBM, AARP, etc. Used for the abbreviation for inch (in.), so it doesn’t get confused with the word in.

Comma (,) Oh, do we have to? There are so many rules! Here are the important ones:

1. Use a comma to separate the two complete sentences that make up a compound sentence.

I am doing the laundry, and I am cleaning the bathrooms.

2. Use a comma to separate items in a series whether they are words, phrases, or clauses.

I like peppers, onions, and mushrooms on my pizza.

I like to ride horses, play volleyball, and knit blankets.

3. Use a comma after introductory words, phrases, or clauses.

Finally, we are going to Paris.

After the movie, we are going to dinner.

Whenever we go to dinner, we eat dessert.

4. Use a comma to set off interrupters in a sentence.

I know, however, that he isn’t home.

The world, in my opinion, is flat.

The watch, which I got on sale, is very valuable.

5. Use a comma with quotations.

He said, “I am not hungry yet.”

“I am not hungry yet,” he said. TIP: Commas always go inside quotation marks in American English. Periods do too, by the way.

6. Use a comma with direct address.

Mary, clean your room.

Clean your room, Mary.

No, Mary, he isn’t here yet.

7. Use a comma with dates and addresses (sometimes).

I was born on September 8, 1980, in Lincoln, Nebraska, on a Friday afternoon.

I was born in September 1980 in Nebraska on a Friday afternoon.

He lives at 45 Main St., Boston, MA 01932

8. Use a comma with contrasting elements.

She was tall, yet graceful.

It was a warm day, but very rainy.

9. Use a comma when not using one would cause confusion.

While we were eating, ants arrived on our blanket.

The two dresses were blue and white, and green and gray.

Semicolon (;) Use a semicolon to separate two sentences that are closely related when you do not want to make two separate sentences or use a conjunction and comma. (Semicolons always goes outside quotations marks.)

I went to college in Boston; my brother went to school on the West Coast.

Also use a semicolon (or rewrite) to clear up a series that already has commas.

The committee included Jane Green, the major; Jim Cotton; Helen Cleary; the comptroller; and four other employees.

Colon (:) Use a colon to introduce a list whether it is horizontal or vertical. (Colons are also used in digital time). Colons can also be used to introduce other things, such as quotes, but not in dialogue. (Colons always go outside quotation marks.)

Please buy these ingredients: chcolate, flour, sugar, and milk.

In his speech the major talked about the new mall: “I think the economy of our city will be greatly enhanced by the 101 additional businesses in the new mall.”

Question Mark (?) Use a question mark after a question. Question marks can go inside or outside quotes, depending on the sentence.

He asked, “Are we there yet?” (Quote is a question.)

Did he say , “I recognize you”? (Whole sentence is a question.)

Did he ask, “Are we there yet?” (Both sentence and quote are questions.)

Exclamation Point (!) Use when expressing emotion. Please don’t use more than one at a time. Please (!). With quotes, follow the same guidelines as with question marks.

Hyphen (-) Use a hyphen in compound words (sometimes). Consult a dictionary if you are unsure if a word has a hyphen; if you can’t decide (or dictionaries disagree), just be consistent! Hyphens also split words on the syllable at the end of a line—mostly before computers. (There are no spaces around hyphens.)

Dash (—) A short dash (en dash, longer than a hyphen) is used in number ranges and as the minus sign. The long dash (em dash) is used to indicate a big break in thought. Please don’t overuse long dashes. They have no real place in formal writing. (There are no spaces around dashes.)

My dog—he isn’t trained yet—is in a crate all night. (You can also use parentheses, but don’t use commas. You might be trying to connect two complete sentences with a comma—a definite NO-NO.)

Parentheses ( ) Use parentheses to enclose additional information. If the content of the parentheses is a complete sentence, punctuate it as such.

Turn to Chapter 5 (page 66).

Turn to Chapter 5. (This chapter is the most challenging one in the book.)

Brackets [ ] Use brackets if you need parentheses inside of parentheses. Also use brackets to explain part of a quote that may not be understood because it was taken out of context.

The President said, “It [the war] will cost us over 6 billion dollars.

Quotation Marks (“) Use to enclose the exact words someone says. Also use to enclose short stories, poems, song titles, articles, chapter titles, and other parts of larger things. Use italics for books, movies, CDs, magazine titles, and other larger things.

Single Quotations (‘) Use single quotes only for quotes inside of quotes. Do not use them for emphasis! Use italics, or sometimes double quotes, for emphasis.

Apostrophes (‘) Use apostrophes to indicate possession. Use apostrophes to form contractions. TIP: Don’t use apostrophes in plurals (please) unless not doing so would cause confusion.

A‘s, 1990s, ’90s (all correct).

Ellipsis ( . . . ) Use to indicate missing words in a sentence or a trailing off at the end of the sentence. Often used in dialogue. Use three periods with spaces between each, and if you use an ellipsis at the end of the sentence, use four periods.

OK. Now for the fun. I told you to wait until the end. Here are some links to more unusual punctuation marks, for example, the interrobang!

Happy Punctuation Day!

P.S. If you are new to the blog, please look at the other Grammar Diva blog posts!

September 13, 2013

Winston Tastes Good Like (As) a Cigarette Should!

Like Versus As

You may not be old enough to remember the television commercial in the headline of this post. However, it is commonly used as an example of incorrect grammar: the difference between the use of like and as.

And it is a very common error. Like is often used when as, as if, or as though should be used instead.

In fact, recently I edited a couple of novels, where I couldn’t decide whether or not to change like to make it correct. If the grammatical mistake was in dialogue, I figured that the character would probably say it that way, so I didn’t correct it. You can get away with a lot in dialogue! If it was in the narration, I still pondered over whether or not to change it. After all, we must consider the narrator ‘s grammar as well.

Well, enough of this….what is the rule, anyway?

Like is used for simple comparisons. It is generally followed by just a noun.

As, as if, and as though are used when they are followed by a clause—a group of words contining a subject and a verb. Compare these two correct examples:

She acted like a queen.

She acted as if she were a queen.

The first example is a simple comparison between she and queen.

In the second example, there is a clause after the as if. She is the subject and were is the verb.

Now look at the slogan in the headline:

“Winston tastes good like a cigarette should.”

(The verb taste is actually implied, but not there, after should: Winston tastes good like a cigarette should taste.)

These, therefore, are both correct grammar:

Winston tastes like a cigarette. (meaning that Winstons taste like cigarettes–a simple comparison)

Winston tastes good, as a cigarette should (taste).

Here are some examples of like and as used correctly:

She talks like a New Yorker.

She talks as if she is from New York.

Mabel acts like the boss.

Mabel acts as if she is the boss.

It looks like rain.

It looks as if it will rain.

So, to sum up….

Use like if what follows is just a noun, or a noun modified by an adjective.

Use as (or as if or as though) if what follows is a clause with a subject and a verb.

Well, it seems like a nice day, so it looks as though this is the end of this blog post!

September 7, 2013

More Misplaced Modifiers: Prepositional Phrases

Prepositional Phrases

In last week’s post, we talked about the correct placement of the words only and almost. The week before that we talked about dangling participles. This week we continue our discussion of the correct placement of modifiers with prepositional phrases.

Here is an example of a prepositional phrase that is in the wrong place in the sentence:

She walked her dog in a bikini.

Unclear? Fuzzy? Silly? Yup! Those are words that describe incorrectly placed prepositional phrases. Although we might assume that it was the girl who was wearing the bikini, who really knows? The sentence says it was the dog who was wearing the bikini because the phrase in a bikini comes right after dog.

First, let’s talk about what prepositional phrases are. A phrase is a small group of related words without both a subject and a verb. Prepositional phrases can function as adjectives or adverbs, describing nouns or verbs, so they commonly tell where, when, or what kind.

All prepositional phrases have the same basic structure. They begin with a preposition (one of the parts of speech), followed by an article (not always, but much of the time), and then a noun or pronoun. Remember that the articles are a, an, and the. There may be additional words, such as an adjective describing the noun in the phrase.

Here are some prepositional phrases that tell where:

over the rainbow

in the kitchen

around the corner

at school

up the spiral staircase

Here are some prepositional phrases that tell when:

after the game

before breakfast

past midnight

within the hour

Here are some prepositional phrases that tell what kind or which one:

with the blue stripes

for my friend

Prepositional phrases should generally be placed near what they describe. Often they fit best at the beginning of the sentence. One place they do not belong is near a word that they don’t describe.

Let’s look back at our first example:

She walked her dog in a bikini.

There are always many ways to fix a sentence. One way to fix this one would be to put the prepositional phrase in a bikini at the beginning of the sentence.

In a bikini, she walked her dog. Or,

Wearing a bikini she walked her dog. Or

While she was wearing a bikini, she walked her dog.

Here is another example. In this sentence, the mistake is much less obvious:

Several people congratulated him on his speech at the end of the meeting.

Can you find the problem? It sounds as if his speech was at the end of the meeting. The sentence probably means to say that several people congratulated him at the end of the meeting.

At the end of the meeting, several people congratulated him on his speech.

Here are a few more examples:

I heard about the meeting in the men’s room.

Was the meeting in the men’s room? That is what the sentence says. More likely, you heard about the meeting while you were in the men’s room.

While I was in the men’s room, I heard about the meeting. Or

In the men’s room, I heard about the meeting.

Did you see the hurricane on the morning news?

Was there really a windy newsroom?

Did you see the report about the hurricane on the morning news?

That desk is perfect for a college student with large drawers and sturdy legs.

I guess you see the problem here!

That desk with large drawers and sturdy legs is perfect for a college student.

As you can see, the mistakes in placement are easy to make! But they are also easy to fix. All it takes is a little care while writing and maybe some proofreading. Although much of the time, the reader will “get” what you are saying, it is much clearer to put things where they belong.

Arlene Miller, also known as The Grammar Diva, has written the two popular books you see here as well as a grammar lesson plan book. She is a teacher, author, speaker, grammar and business writing workshop facilitator, and a copyeditor. She is a member of Redwood Writers and a board member of the Bay Area Independent Publishing Association. Come hear her grammar workshop at the Sonoma County Book festival on September 21 at 3:15.

Click on either book to buy!

August 31, 2013

A Little Lesson About “Only”

In last week’s blog post, I talked about dangling participles, one of the categories of misplaced modifiers. Misplacement of the word only can also be described as a misplaced modifier. A modifier is something that describes or somehow changes something else in the sentence. Modifiers are generally either adjectives (modify nouns and pronouns) or adverbs (modify verbs) or some other grammatical structure being used as an adjective or adverb.

The word only is sometimes an adjective (only child) and sometimes an adverb (I only danced in my last play; I didn’t sing.)

The placement of only in a sentence can really change the meaning of the sentence, as you will see in the series of sentences below. However, most of the time, the placement of only is not a problem at all. There is one common misplacement of only, and it is extremely common and usually is not even noticed. (Yes, I notice it much of the time, but it usually doesn’t really affect anyone’s understanding of the sentence.) But first, look at these sentences, all with only in a different place, giving each sentence a completely different meaning

Only Judy kicked her friend in the leg. (Modifies Judy. No one else kicked the friend, just good old Judy.)

Judy only kicked her friend in the leg.(Modifies kicked; she kicked her friend, but she didn’t do anything else to her.)

Judy kicked only her friend in the leg. (Slightly different meaning: Judy didn’t kick anyone else, just her friend, thank goodness!)

Judy kicked her only friend in the leg. (Modifies friend; no surprise this was her only friend.)

Judy kicked her friend only in the leg. (She didn’t kick her anywhere else.)

Judy kicked her friend in her only leg. (Modifies leg; poor friend.)

Now, no one is going to say Judy kicked her only friend in the leg, when he or she really means Judy kicked her friend in her only leg. However, there is a sentence in that list that is often used instead of the one that is really meant. Can you find those two sentences?

The answer? Sentence #2 is often used to mean Sentence #5. The person saying it would emphasize the word leg, and it would probably sound OK to many people (yes, you’re right; not to me…)

Here is another similar example:

I only have five dollars.

The correct way to phrase this is I have only five dollars.

Only goes with the five dollars, not with have.

Another similar word is almost. Check out these sentences:

We almost made ten dollars.

We made almost ten dollars.

Although many people would say or write the first sentence when they actually mean the second sentence, they have different meanings. In the first sentence, you may have been selling a book for $10. Someone was very interested in the book and nearly bought it, but they didn’t. So, you didn’t make any money. But since they almost bought it, you could have made ten dollars; in other words, you almost made ten dollars.

In the second sentence, you actually did make some money; you made almost ten dollars. So, perhaps you made $9.99!

Although many times no one will notice the placement of only or almost, and will assume the intended meaning anyway, you might want to add this to your bag of grammar tricks!

August 29, 2013

Special Edition: “Bloglight” on Linda Jay Geldens

Linda Jay Geldens

I have known Marin-based copyeditor and promotional writer Linda Jay Geldens for a while through BAIPA (Bay Area Independent Publishers Association), where we both sit on the Board, Linda Jay as newsletter editor and me as Board Secretary. I knew Linda was a great copyeditor; after reading a book that she edited and finding it flawless, I hired her to copyedit my second grammar book. But until more recently, I didn’t know some very interesting facts about Linda!

Linda’s father was a radio and TV writer who worked with Rod Serling before The Twilight Zone; in fact, as a child, Linda vacationed with her family and the Serlings.

Linda dated Governor Jerry Brown when they were students at UC Berkeley and Jerry’s father Pat was governor.

Linda used to be a professional jazz singer, and when she was 19 she had a gig at the Hangover Lounge in her hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio, singing jazz while standing on a piano!

Linda Jay was born in New York City to a Methodist dramatic writer (who had studied to become a minister) and a Jewish kindergarten teacher. An only child, Linda moved a lot because her dad was a freelance writer, but she always connected to her new environment by joining the staff of the school newspaper. Her parents teamed up to write murder mysteries and dramas on TV and radio from the 1940s through the 1970s. Their writing included two scripts for the famous radio show The Shadow in the 1940s. Her father, Verne Jay, also wrote an episode of the TV series Gunsmoke. While he was working for WLW, the NBC radio station in Cincinnati in 1950, a new writer was hired. His name was Rod Serling. Rod and Linda’s dad teamed up to write a murder mystery, A Walk in the Night, for the Phillip Morris Television Playhouse before Serling moved to Hollywood to find his fame and fortune — which he did with The Twilight Zone.

Linda Jay, always an English major, started college at Miami University in Ohio. On Serling’s recommendation, she transferred to Antioch. After leaving Antioch, Linda went to New York City for several months, where she hung out in Greenwich Village listening to jazz, while working as a secretary at Columbia University. She then moved to California to attend UC Berkeley, where she met Jerry Brown at the International House, where they both lived. On their second date, he said they were going to Sacramento to visit his parents. Linda had no idea who his father was! When Jerry said his father was the Governor, Linda was just a little surprised!

Eventually, Linda attended George Washington University in Washington, DC, where she graduated with her degree in English.

Her first job out of school was for the well-known Boston publishing house, Little-Brown, where she was an advertising copywriter. Since then, Linda has written for The Artist’s Magazine, Television Technology, websites, blogs, and book covers. She has also been editing manuscripts consistently, about 25 books a year, ranging in genre from business to memoir to fantasy to spirituality.

Her Favorite Genre: Linda’s favorite genre to edit is memoir. “You get the whole picture of someone’s life,” she says. “Not just the facts, but what they’re really all about — their heart, their soul.”

Her Most Unusual Projects: At 19, Linda edited The Tight White Collar, a novel by Grace Metalious, the author of Peyton Place. She also wrote the back cover copy for Johnny, We Hardly Knew Ye, a book about John F. Kennedy. Most recently, Linda collaborated on the book Ring EXchange — Adventures of a Multiple Marrier by Pam Evans.

Linda says, “I don’t have a book in me. I have many 1500-word articles in me. In six months I will be 75 years old, and I have just barely scratched the surface of what I can do in editing and writing. Odd, huh?”

Linda is an expert copyeditor, or line editor.She goes over every line of a manuscript to make sure it is publisher-ready, whether it is to be self-published or traditionally published. It is extremely important to her that she not change the author’s authentic voice and that all final decisions belong to the author.

Her grammar pet peeves? “Between you and I” (rather than “me”) and “lay and lie.”

Although we are both copyeditors, we are friends and not really competitors. I would be the first to tell you that Linda is a great editor. We will be representing BAIPA at the Booktoberfest at the Mechanics Institute in San Francisco on September 27.

If you would like to contact Linda Jay, her e-mail is LindaJay@aol.com.

August 23, 2013

Don’t Dangle Your Participles!

Dangling Participle!

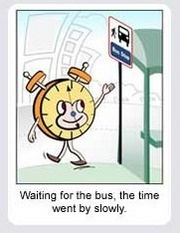

You might read the sentence underneath the cartoon on the left and not notice that anything is wrong with it. But read it again (or just look at the picture) and you see that it makes no sense — and is in fact ridiculous. We probably read, write, and speak such sentences frequently without even noticing what they really say! We call this particular error a dangling participle. They are best avoided! The way to avoid writing them is to be careful.

The caption under the cartoon means that time passed slowly for the person waiting for the bus. But is that what the sentence says as it is written? No. It says (and illustrates) that the time is waiting for the bus. Why does it say that? Well, in the English language, , words are assumed to go with other words or phrases that are near them. Since time is placed right after the participial phrase waiting for the bus, it is assumed that they go together and that waiting for the bus describes the word time.

Let’s start out by defining what a participle is. You know what a verb is. A verb is usually an action word of some kind, even if it isn’t a physical action (for example, think, wonder, assume, and determine are not physical actions, but they are verbs). A participle is one of the verbals — it used to be a verb, but it is now an adjective. An adjective is not an action word; an adjective describes a noun (person, place, thing, or idea) or a pronoun (I, me, you, they, he, etc.).

A participle comes in one of two types: present or past. So we need to take a verb and add something to it to make it an adjective. To make a present participle, we add -ing to the end of the verb. To make a past participle, we use the past tense form of the verb (often an -ed ending, but not always).

Here are some present participles in sentences:

1. The growling dog tried to bite the child. (The participle growling comes from the verb to growl, but is now an adjective describing dog. (Note that in the sentence The dog is growling at the child, growling is no longer a participle; is growling is now a verb.)

2. I saw a dancing elephant at the circus. (The participle dancing comes from the verb to dance, but is now an adjective describing elephant.)

Here are some past participles in sentences:

1. Skating on a frozen lake can be dangerous. (The past participle frozen comes from the verb to freeze in its present perfect form — the form you would use with “has” or “have” or “had.” It is now an adjective describing lake.)

2. The burned building was unrecognizable as the school that it once was. (The past participle burned comes from the verb to burn in its present perfect form — the form you would use with “has” or “have” or “had.” It is now an adjective describing building.)

It is when we use a participle in a phrase (a few related words strung together), usually to begin a sentence, that we run into trouble with dangling participles. (However, it doesn’t have to be a phrase, and it doesn’t have to be at the beginning of the sentence, as the examples below will show.) Since the participle or participial phrase is an adjective, it is thought to describe whatever noun or pronoun comes right after it. Therefore, you want to make sure that when you are writing, you place whatever that participle or participial phrase is describing, or modifying, directly after the phrase!

Here are some goofs!

1. Reading the newspaper by the window, my cat jumped into my lap. (Who was reading?)

2. Growling, I fed my hungry dog. (Who was growling?)

3. While still in diapers, my mother remarried. (Who was still in diapers?)

4. I saw the beautiful red tulips running down the street. (What was running down the street?)

5. Freshly painted and waxed, I picked my car up from the shop. (Who was freshly painted and waxed?)

There are usually several ways to correct a sentence. Here is one way to correct each of the above examples. In these “fixes,” the sentence was rewritten without participial phrases.

1. While I was reading the newspaper by the window, my cat jumped into my lap.

2. Because my dog was growling from hunger, I fed him.

3. My mother remarried while I was still in diapers.

4. I saw the beautiful red tulips as I was running down the street.

5. My car was freshly painted and waxed when I picked it up from the shop.

You could rewrite the sentences keeping the participial phrases, but the rewrite might be awkward or change the meaning of the sentences, so it isn’t necessary to keep the structure the same. Here are the “fixes” using the same participial phrases:

1. Reading the newspaper by the window, I was surprised when the cat jumped into my lap.

2. Growling, my hungry dog was finally fed.

3. While still in diapers, I saw my mother remarry.

4. Running down the street, I saw the beautilful red tulips.

5. Freshly painted and waxed, my car looked great when I picked it up from the shop.

It is easy to correct the mistakes once you notice that your participle or participial phrase is dangling and doesn’t make sense. One way to find these mistakes is to carefully proofread your writing!

There are other things in sentences that can also be misplaced. But that’s another blog post!

Til next time -

The Grammar Diva

August 16, 2013

How to Write Possessives

How to Write Possessives

Possessives are one of the three cases in the English language (the other two are nominative and objective, but let’s not worry about those!). Latin has five cases and some languages have seven or eight, so we are doing well here. In any case (pardon the pun), possessives imply ownership.

We all learned in grade school that to make a noun possessive, we add an apostrophe and an s. Not wrong, but not the whole story.

The only words that can be made possessive are nouns and pronouns. People have difficulty with both. Just remember that no possessive pronouns have an apostrophe! Here are the possessive pronouns:

First person singular: my, mine

Second person singular and plural: your, yours

Third person singular: his, her, hers, its (without the apostrophe)

First person plural: our, ours

Third person plural: their, theirs

Okay. Now on to the nouns.

Generally, for singular nouns you add an apostrophe and an s to make them possessive:

This is Mary’s book.

My dog’s bowl is empty.

Your essay’s introduction is very good. (Doesn’t need to be a person to be a possessive.)

Plural nouns that don’t end in an s are also made possessive by adding an apostrophe and an s.

The children’s playground is across the street.

The mice’s home is in that hole in the wall.

Plural nouns that end in s (which is most of them) are made possessive with the addition of only an apostrophe.

Her two sisters’ bikes are in the driveway. (One sister’s bike; two sisters’ bikes)

The parties’ themes were both tropical. (One party’s theme; two parties’ themes)

Most singular nouns that end in s or ss are made possessive by adding an apostrophe and an s (yes, really!)

The bus’s tire is flat. (Think of how you would pronounce it. It is spelled exactly as you would say it.)

My boss’s desk is really messy. (Once again, that is how you would say it.)

Thomas’s new car is over there. (You wouldn’t pronounce it Thomas new car, would you??)

I had to memorize Frederick Douglass’s speech. (Yup!)

The princess’s slipper fit perfectly.

Now, lets talk about a few of those words made plural.

What if you had two bosses, and they both had messy desks? My bosses’ desks are really messy. (You have used the plural of boss, which is bosses, and you have added just an apostrophe, like in other plurals that end in s. Once again, that is how you pronounce it. You don’t add another syllable. You don’t say bosses’s, so you don’t spell it that way either. My boss’s desk and my bosses’ desks are pronounced exactly the same way, even though they are spelled differently–because one is singular and one is plural.)

What if there were three princesses whose slippers all fit perfectly? Same as bosses. The three princesses’ slippers all fit perfectly. (You make princess plural by adding -es, and you add an apostrophe like in plurals that end in s. Once again, princess’s and princesses’ are pronounced the same way, although they are spelled differently because one is a singular possessive and the other is a plural possessive.)

All right. Let’s do the other three examples:

All the buses’ tires are flat. (Bus’s is singular possessive; buses’ is plural possessive)

The two Thomases’ last names both begin with L.(Correct, but you might just want to rewrite it!)

Well, there is only one Frederick Douglass, so I guess we can’t do that one!

Exceptions? Well, of course!

If a word ends in -es that sounds like -ez, you just add an apostrophe to make it possessive — no s.

Examples: Socrates’ (possessive), Hippocrates’ (possessive)

Also, the possessive of Jesus is Jesus’, and I would suppose Moses is treated the same way.

I hear that today is International Apostrophe Day. How appropriate!

If you read these posts on Facebook,Twitter, or LinkedIn, why don’t you subscribe and have them delivered directly to your emailbox?

August 9, 2013

Apostrophes: When To Use Them – And When Not To

Some apostrophes are not OK!

Apostrophes—those things that look like single quotes, or maybe commas hanging in the air—have a couple of uses in the English language. First, they are used for contractions. Second, they are used to indicate possession. We are going to talk all about possessives in next week’s blog post (can you wait?). That leaves us with contractions.

Contractions are word combinations with letters left out to save space, I guess. Or perhaps to make it easy to say in conversation. They slide off the tongue much more easily than two separate words. The apostrophe is put in place of the missing letter (or letters). The common words to be shortened in a contraction are not, have, and are (am, is)

Some contractions with not: didn’t, isn’t, aren’t, haven’t, wouldn’t, won’t, can’t.

Some contractions with have: could’ve, would’ve, I’ve, you’ve, we’ve

Some contractions with the to be verb (are, am, is): I’m, you’re, we’re, he’s, it’s, they’re

Well, you know I’m not writing this blog post to talk about contractions. You know all about them. Almost. So here is all I am going to say about contractions, before I move on to when NOT to use apostrophes:

1. In formal writing (as opposed to conversation or a friendly e-mail), I would suggest avoiding some contractions. The contractions with n’t for not are fine, but I would spell out words such as could have, would have, should have, I have, you have, we are, most of the time. In particular I would not use contractions where the shortened word is have. Is it wrong? No. But it does sound more conversational and less professional.

2. Oh, please, remember that the contraction meaning it is is the one with the apostrophe (it’s).

3. Oh, please remember to put the apostrophe in the you’re that means you are (not your)!

Possessives is the topic for next week, so now we have come to the when not to use an apostrophe part.

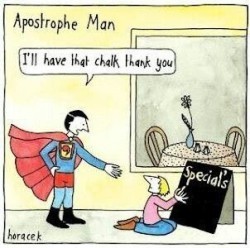

Turn your attention to the apostrophe man cartoon above. Yup, you have seen the apostrophe used this way. You have seen it on signs, you have seen it in menus, and you have seen it on Facebook. DO NOT USE an apostrophe for plurals. Plural words, unless they are plural possessives, do not have apostrophes! EVER, almost. That means no apostrophes in plural words, numbers, letters, or symbols.

The only time you need an apostrophe in a plural is when the word, number, letter or symbol would be confused with another word if there were no apostrophe. Let’s see…how many things does that include?

If you are talking about the letter A, use an apostrophe to make it plural. Otherwise, it will look like as.

I got all A’s on my report card.

If you are talking about the letter I, use an apostrophe to make it plural. Otherwise, it will look like is.

Make sure you capitalize all your pronoun I‘s.

If you are talking about the letter U, use an apostrophe to make it plural. Otherwise, it will look like us.

There are two u‘s in the word uncut.

It doesn’t matter whether you use the letter in uppercase or lowercase.

Also, note that when you use a letter, number, word, or symbol as itself, it is italicized. However, the apostrophe/s is not in italics. This goes for words, numbers, letters, and symbols without apostrophes as well. The s is not italicized.

There are too many ands in your sentence. (The s at the end of and is not in italics.)

Yes, this rule applies to numbers too.

Do you remember the 1960s? (not 1960′s)

Do you remember the ’60s? (Here, the apostrophe is standing in for the 19, making it a contraction of sorts. But there is no apostrophe after 60.

The letters a, i, and u need apostrophes in their plurals to avoid confusion. That is just about it.

Next week, apostrophes return as we talk about possessives.

August 2, 2013

Wake or Awake: What’s the Difference?

Wake or Awake: What’s the Difference?

It seems as if many people are confused about wake and awake. Are they they same? If not, which one is correct? When do I use wake and when do I use awake?

Relax. No matter what you do, you will probably be correct. There is really no difference between the two words. They are a bit confusing, though: (1) They can be used as either transitive or intransitive verbs, (2) Some variations are more commonly used as adjectives, (3) There is some variation in past-tense formation, (4) Some forms may be preferred in passive voice rather than active, and (5) Some forms may be used in a more figurative sense, perhaps in literature.

So while wake and awake aren’t really difficult, it gives me a chance to explain the meanings of several words that are important in the discussion:

1. Transitive verb: A transitive verb has a direct object. A direct object is the noun or pronoun that receives the action of the verb. Examples:

I woke the baby. I awoke the baby is also correct but not as common.

He woke me up. He awoke me is also correct, but not as common.

When used transitively, woke often is followed by up.

2. Intransitive verb: An intransitive verb has no direct object. Examples:

I wake up at 8 a.m. I awake at 8 a.m. is also fine.

He wakes at midnight to go to work. He awakes at midnight to go to work is also correct.

3. An adjective describes a noun, pronoun, or other adjective. Awake is most often use as an adjective. Examples:

I am awake now. (describes I)

I like teaching the awake students! (describes students)

4. Active voice: In a sentence where the verb is in active voice, the subject performs the action of the verb. Examples:

He woke up early this morning.

I woke her up to get to work on time.

5. Passive voice: In a sentences where the verb is in passive voice, the subject is acted upon and doesn’t do anything. Examples:

I was awakened by the dog’s barking.

He was woken up by his roommate.

Generally, awakened is used in the passive voice. However, I have awakened my brother (active voice) is correct, but not as common.

6. Literary: Having to do with literature. Awake and its various tense forms (awakened, awoke, awakening, etc.) is more likely to be used in creative writing, or literature. Wake, woke, woken, etc., is more likely to be used in conversation and ordinary writing. Examples:

I was awakened by the music of the rain. (literary)

The rain woke me up. (conversational)

7. Literal: Not to be confused with literary, literal means “based on the actual meaning of the words used.” Examples:

I woke up late today.

I am awake after all that noise you were making.

8. Figurative: Not in its original, or literal, sense. Awake and its various tense forms (awakened, awoke, awakening, etc.) is more likely to be used figuratively. Examples:

He was awakened to the realities of life at an early age.

Awaken, birds, and sing to me a song of joy!

To sum it up, you can use pretty much whichever word you like, but in general, you will probably use wake more often than awake, except to use awake as an adjective (for example, I am awake now. )

Here is how you conjugate the words:

Wake:

Present: Wake: I wake up. I wake up my brother.

Past: Woke: (or waked , but not common) I woke up. I woke up my brother.

Past Participle: Have woken (or have waked, but not common). I have woken up. I have woken up my brother. I have been woken up.

Awake:

Present: Awake. I am awake.

Past: Awoke (or awaked, but not common). I awoke from my nap.

Past Participle: Has awoken (or has awaked, but not common). Sleeping Beauty has awoken.

Awaken - Can’t forget this one.

Present: I awaken the princess. The princess awakens.

Past: I awakened the princess. The princess awakened.

Past Participle: I have awakened the princess. The princess has awakened.

However, unless you are writing a fairy tale, you can just use wake!

The Origin of Wake (in case you cared)

From Middle English waken, from Old English wacan (to awake),

First known use is before the 12th century.

Origin of Awake

From Middle English awaken, from Old English awacan and awakien.

First known use is before the 12th century.

Something you might want to know about wake and awake:

Knock up is a synonym in British English!

More examples of how you might use these words:

She fell asleep immediately but awoke an hour later.

She fell asleep immediately but woke up an hour later.

I woke her just past midnight.

I awoke her just past midnight.

I awoke several times during the night.

I woke up several times during the night.

I was awakened several times during the night.

I was awake several times during the night.

The baby awoke from his nap.

The baby woke up from his nap.

The baby was awakened from his nap by the doorbell.

The alarm awoke me early.

The alarm woke me early.

They were awoken by a loud bang.

They were woken by a loud band.

July 27, 2013

Quotations with Other Punctuation Marks: You Can Quote Me on This!

Quotation marks are used around the exact words someone says and around certain titles (song titles, chapter titles in books, magazine article titles — see my blog post on quotes versus italics.)

Single quotes (‘), as opposed to double quotes (“), are used for quotes inside of quotes and nothing else. Do not use single quotes to emphasize text (do not use double quotes either); use italics or bold for emphasis.

It is often necessary to use other types of punctuation along with quotation marks: commas, periods, colons, semicolons, question marks, and exclamation points. So which comes first, the quotation marks or the other punctuation? Well, it depends….

Here are the rules:

1. Periods and commas ALWAYS go inside the quotation marks. ALWAYS.

Examples:

“Make sure you pack your summer clothes,” Mom said.

Mom said, “Make sure you pack your summer clothes.”

She said, “My favorite song is ‘Somewhere over the Rainbow.’” (Yes, even when there are three quotation marks, one belonging to the song title and the other two belonging to the whole quote. The period or comma is inside all three quotation marks.)

2. Semicolons and colons ALWAYS go outside the quotation marks.

Example:

She said, “I don’t know what to do”; he answered “I don’t know what to do either.”

It is probably never necessary to use colons and semicolons with quotations marks, so I wouldn’t worry about this one.

3. Question marks and exclamation points …. WELL, IT DEPENDS. These can go either way,

If the question mark or exclamation point belongs to just what is in the quotes, it goes inside the quotes.

If the question mark or exclamation point belongs to the entire sentence, it goes outside the quotes.

If the question mark or exclamation point belongs to both, it goes inside the quotes. Just use one.

Examples:

He said, “Who are you?” (The question mark belongs to the quote only and it goes inside.)

Did he say, “I am John”? (The whole sentence is a question, but the quote itself isn’t. The quote goes outside.)

Did he ask, “Who are you?” (The quote is a question, and the whole sentence is also a question. Don’t use two question marks. Use only one, and place it inside the quotation marks.)

Exclamation points are treated exactly the same as question marks.

He screamed, “Help me!” (Quote itself is the exclamation, so the mark goes inside the quotes.)

He had the nerve to say to me,”You are an idiot”! (The whole sentence is exclamation, but the quoted part really isn’t . Mark goes outside.)

I freaked out when he screamed, “You are on fire!” (Both the quoted portion and the whole sentence are exclamations. Use one mark and put it inside.)

Please refrain from using question marks and exclamation points together.

He screamed, “Do you know the way?” ( You don’t need an exclamation point after the quotes. It already says he screamed.)