Arlene Miller's Blog, page 66

November 29, 2013

Parallel Structure Is Crucial to Good Writing

What is parallel structure, anyway? Isn’t parallel a term that belongs in math class?

Parallel structure means that elements in your sentences or lists are expressed with the same syntax, or wording. For example, all the items in your lists should be complete sentences—or none of them should be complete sentences. If you have a series of phrases or clauses in a sentence, they should all be expressed using the same structure.

Parallel structure is important in

1. writing lists

2. writing series in sentences

3. using correlative conjunctions (Correlative conjunctions are the connectors that come in pairs: either/or, both/and, not only/but also, whether/if, neither/nor.)

1. Here is a list that is not parallel:

At this seminar you will learn

how to be a better manager

how to inspire your employees

how to use your time effectively

evaluating your employees fairly

how to handle office conflicts

It is easy to see which item in the list is not parallel. The item that begins with “evaluating” should read how to evaluate your employees fairly.

2. In addition to parallelism in lists, it is important to structure your sentences so that that are parallel. Here are some examples:

Not parallel: When writing your essay, you should check for correct grammar, capitalize all your proper nouns, and it is important to use transition words.

Parallel: When writing your essay, you should check for correct grammar, capitalize all your proper nouns, and use transition words.

In the parallel sentence above, the clauses all begin with verbs.

Here is another example:

Not parallel: On our trip to Paris, I wanted to go shopping, eat in nice restaurants, and visiting my old friends.

Parallel: On our trip to Paris, I wanted to go shopping, eat in nice restaurants, and visit my old friends.

Not parallel: When I shop for Christmas gifts, I pay close attention to the price of the gift, the quality of the item, and whether my friend will like it.

Parallel: When I shop for Christmas gifts, I pay close attention to the price of the gift, the quality of the item, and the appropriateness of the item for that friend.

3. It is also important to use parallel structure when you use correlative conjunctions. Here are a few examples:

Not parallel: I like to spend my free time either reading or I will go to the movies.

Parallel: I like to spend my free time either reading or going to the movies.

Not parallel: I love both salads and grilling a steak.

Parallel: I love both putting together a salad and grilling a steak. (There is always more than one way to fix something. Of course, you could also say I love both salad and steak.)

Not parallel: I don’t know whether my brother is driving from Arizona or he might take the train.

Parallel: I don’t know whether my brother is driving from Arizona or taking the train.

Parallel writing flows much better and doesn’t have that awkward sound that “nonparallel” writing has. It is easy to overlook mistakes in parallel construction, so always proofread!

Remember that books make great holiday gifts, either in paperback or ebook format. And what better gift can you give this season than the gift of better writing?

November 22, 2013

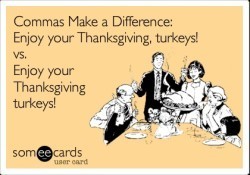

Some Real Grammar Turkeys! Happy Thanksgiving!

Ah, Grammar: The difference between knowing your shit and knowing you’re shit….

Ah, Grammar: The difference between knowing your shit and knowing you’re shit….

I thought for turkey week, I would write a blog with some real grammar turkeys! Hope you get a chuckle or two…

Some of My Favorite Goofs

Ambiguous modifier: Visiting relatives can be boring.

Misplaced modifier: For sale: Beautiful oak desk perfect for student with large drawers

Shouldn’t there be a comma somewhere? I just love to bake children.

Misplaced modifier: While still in diapers, my mother remarried.

Ambiguous modifier: He heard about the wedding in the men’s room.

Misplaced modifier: Wanted: A room by two gentlemen 30 feet long and 20 feet wide.

Some Real Newspaper Headlines

4-H Girls Win Prizes for Fat Calves

Big Ugly Woman Wins Beauty Pageant (Newspaper in town of Big Ugly, WV)

Body Search Reveals $4,000 in Crack (from the Jackson Citizen-Patriot, Michigan)

Chef Throws His Heart into Helping Feed Needy (from the Louisville Courier Journal)

Drunk Gets Nine Months in Violin Case

Eye Drops off Shelf

Hospitals are Sued by 7 Foot Doctors

Include your Children When Baking Cookies

A Little More Humor…

Butcher’s sign: Try our sausages. None like them.

A tailor’s guarantee: If the smallest hole appears after six months’ wear, we will make another absolutely free.

Lost: A small pony belonging to a young lady with a silver mane and tail.

Barber’s sign: Hair cut while you wait.

Lost: Wallet belonging to a young man made of calf skin

How About These?

It takes many ingredients to make Burger King great, but the secret ingredient is our people. (Yuck)

Slow Children Crossing

Automatic washing machines. Please remove all your clothes when the light goes out.

“Elephants Please Stay In Your Car.” (Warning at a safari park).

And Some Easy-to-Understand Jargon!

These guidelines are written in a matter-of-fact style that eschews jargon, the obscure and the insular. They are intended for use by the novice and the experienced alike. [From the United Kingdom Evaluation Society 'Guidelines for good practice in evaluation']

This is a genuine ground floor opportunity to shape a front line field force operating in a matrix structure. [As stated on the 'Take a Fresh Look at Wales' website]

The cause of the fire was due to a malicious ignition incident that was fortunately contained to the function and meeting room area of the hotel. [News statement about a fire at a hotel]

Its clear lines and minimalist design provide it with an unmistakable look. It is daring, and different. So that your writing instrument not only carries your message, but lives it. [Promotional literature for ... pens]

Where the policy is divided into a number of distinct arrangements (‘Arrangements’) where benefits are capable of being taken from on Arrangement or group of Arrangements separately from other Arrangements, then this policy amendment will not apply to any Arrangements in respect of which the relevant policy proceeds have already been applied to provide benefits. The policy amendment will apply to all other Arrangements under the policy. [Policy amendment, Norwich Union]

And here is one that truly appeared in the newspaper; it was intended as a brief description of a Peter Ustinov documentary:

“Highlights of his global tour include encounters with Nelson Mandela, an 800-year-old demigod and a dildo collector”. (This quote is obviously British, since the period is after the quotations! And look what can happen if you leave out the Oxford comma!)

I you haven’t had enough yet, please check out these websites for some funny bad grammar/spelling photos:

10 Unfortunate Grammar and Spelling Mistakes - http://www.buzzfeed.com/copyranter/10-more-unfortunate-grammar-and-spelling-mistakes

15 Hilarious Newspaper Errors - http://www.oddee.com/item_97261.aspx

Grammar Mistakes on Signs - http://www.bitrebels.com/lifestyle/grammar-mistakes-on-signs/

Punctuation Mistakes in Advertising - http://theadgrad.wordpress.com/2010/05/22/the-three-most-hideous-punctuation-errors-in-advertising/

Enjoy your turkey!

November 15, 2013

It’s All About “The”….

funny thing about “the”…

Another inspired blog post…..last week’s blog post was inspired by a former student of mine. This week’s blog post was inspired by something I heard on the radio this week. I was listening to KGO 810 AM and heard Ronn Owens, a popular KGO host, talking about the word the. I started thinking about the quirkiness of the word and decided it would make a fun post.

The is, of course, an article in the English language, along with a and an. In fact, I wrote a post about articles just a couple of weeks ago. But this is different.

Ronn Owens, if you read this post, please know that I borrowed some things from your broadcast, but I am giving you full credit, and I will post the link to the radio show at the end of this post!

Okay. So what does the word the mean? What is it used for? It is the definite article in the English language . The indefinite articles are a and an. When you talk about “a book,” you could be talking about any book (using the indefinite article). However, when you talk about “the book,” you are talking about a specific book (using the definite article). That part is pretty straightforward.

Most languages have articles, but then some don’t. For example, Japanese and Russian don’t have articles. However, before you think how much less confusing that might be, consider that French and Spanish are among the languages that have articles with gender! Every noun is either feminine or masculine, and the gender doesn’t really have much to do with the noun at all. In French, the indefinite pronoun is un (masculine) or une (feminine). The definite pronoun (the in English) is la for feminine, le for masculine, and les for plural. And German has masculine, feminine and neuter articles!

But back to English. The is a quirkly word in itself, and someone new to the language must have a difficult time figuring out whether or not to put the before a world at all. Consider these:

Up here in Northern California, we travel (or sit in traffic) on 101. In Massachusetts (I know because I used to live there), we risk our lives on 128 and 495. But (and if you watch Saturday Night Live, you know all about this one)….you take the 405 to the 110. (Forgive me if I have my freeways confused!) So why don’t we take the 101?

In Boston you take the T. But in San Francisco, you don’t take the BART. You take BART.

In America we go to the hospital, but in Britain, you go to hospital.

You go to the mall, to the park, to the store, and to the lake…..but you go to school and to work. You can go to the school, but it implies a slightly different meaning. Perhaps we don’t put the in front of school or work because they are repetitive activities, more like verbs in a way. You go to school, if you attend regularly. You go to the school if you are visiting, or if your child is in trouble there.

You go to the Golden Gate Bridge, the Empire State Building, and the Grand Canyon. But you go to Yosemite.

You go to the police station. But then you go to jail.

You go to the bathroom. But then, you go to bed.

You take the bus and the train, but do you take the plane? Taking the plane sounds as if you stole it. Most of the time we simply fly.

You go to the bank. But then you pay your taxes at city hall.

You go on the rides at the fair, but then you eat funnel cake and fried Twinkies.

You get the point….it sure takes the cake……

Here is a link to the podcast of Ronn Owen’s November 11 show….it is November 11, 11 a.m. segment, about 15 minutes in.

November 8, 2013

Weird and Wonderful Words (Part 1 A–D)

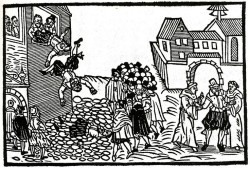

The Defenestration of Prague

A couple of years ago, one of my seventh grade students told me about this great word she had learned (I don’t know where she had learned it). The word was defenestrate, which means to throw something or someone out of a window. This was a new word for me too (not being much of a history student, it turns out). She was such an enthusiastic student, and I liked the word so much, I added it to my students’ vocabulary list, where it remains to this day. All the students love the word and I doubt if any of them will ever forget what it means! In fact, when we were recently talking about their novel, The Outsiders, and I asked them how Ponyboy and Johnny saved the children from the church fire, they replied (with glee, I might add), “They defenestrated them!”

Turns out that the word was coined in 1618 from the Latin prefix de (down or away from) and fenestra, which means window. It originates from two incidents in Prague, known as the Defenestrations of Prague. In 1419 several town officials were thrown from the windows of the town hall. Then, in 1618, two imperial governors and their secretaries were tossed from Prague Castle. This event began the 30 Years War. Who knew?

So, I decided to find some other fascinating words I could tell you about. Thus, I launch the Weird and Wonderful Words Series. The posts won’t appear every week; after all, there is still grammar to be done! Today, here are ten unusual words that begin with the letters A, B , C, and D.

Although my company is called bigwords101, I am not a proponent of using big, fancy words in your speech or writing. However, sometimes new and unusual words can be fun to use!

1. aglet (noun) – You may know this one. I once knew it, but quickly forgot. The aglet is that plastic thingie at the end of your shoelace. (Origin: 1400-1450 from Middle English and Middle French).

2. bastinado (noun) – This is a type of torture by beating the soles of the feet (or sometimes the buttocks) with a stick. (Origin: 1570-1580 from the Spanish baston, meaning stick.)

3. bibcock (noun) – This is a faucet that has a downward-bent nozzle (origin 1790). Question: Don’t they all? Wouldn’t we get really wet otherwise?

4. bibliobibuli (noun) – Obviously from biblio, meaning book. This one was coined by H.L. Mencken in 1957: ”There are people who read too much: the bibliobibuli. I know some who are constantly drunk on books, as other men are drunk on whiskey or religion. They wander through this most diverting and stimulating of worlds in a haze, seeing nothing and hearing nothing.” So there! Proud to be one!

5. boondoggle (noun) – This word refers to unnecessary activity or wasteful expenditure. It is an Americanism apparently coined around 1930 by R. H. Link, an American scoutmaster, referring to simple tasks the scouts were taught.

6. bumf (noun) – Slang for toilet paper and informal for junk mail and other worthless paperwork. It is 1889 British schoolboy slang.

7. cataglottism (noun) – This one, as bibliobibuli, is in the Urban Dictionary. It is from the Greek cato (down) and glotta/glossa (tongue). You figure it out! Seriously, it means French kissing.

8. corybantic (adjective) – This one means frenzied or agitated, so you will probably be able to put this one to work pretty quickly! In classical myth, Corybants was a wild attendant of the goddess Cybele.

9. defenestrate (noun) – To throw something or someone out the window.

10. discalced (adjective) – This word means barefooted, usually referring to friars and nuns who wear sandals. (Origin: 1625 from the Latin)

Would you rather be defenestrated or the victim of bastinado when you are discalced?

November 1, 2013

“A” Historic Blog Post

Articles: A, An and The

I have been asked several times recently (mostly by writers) about using a versus an. The questions were primarily about which of these articles to use in front of the word historic. Is it a historic or an historic? They both sound all right, but are they? Well, the old rule still applies: Words that begin with a vowel sound (not necessarily a vowel, just a vowel sound) use an. Words that begin with a consonant sound (not necessarily a consonant, just a consonant sound) use a. Some words that begin with h, like historic, have a definite consonant sound at the beginning; others, such as honor, begin with a vowel sound.

For some reason, both a and an sound natural with historic (and other similar words).

Following the rule, use an with honor (it begins with an o sound—the h is silent). However, use a with historic, since the h, a consonant sound, is pronounced.

These words should be prefaced with the article a:

historic

hysterical

These words should be prefaced with the article an:

honor

herb

You may notice that when you put the a in front of historic, you pronounce is as a long a, while in front of most words you would pronounce it “uh.” But pronouncing it isn’t so much of a problem; that is simply the way it rolls off the tongue—which is exactly why a fits in front of some words, and an fits in front of others.

Follow the basic rule, and you won’t go wrong.

What about the other article, the? Well, the goes in front of any letter. However, you will notice that there are two ways to pronounce it . One way is thuh (rhymes with duh); the other way is thee (rhymes with tree). When you put the before a word that begins with a vowel sound, you will automatically say thee because it just rolls of the tongue that way. Before a consonant sound, you will generally say thuh. Try saying the in front of historic. You might say it either way because, once again, they both sound okay. Since the is always spelled the same, there is no problem here.

Not already a subscriber? Subscribe to The Grammar Diva Blog!

Want more grammar, punctuation, word usage, and writing information?

October 25, 2013

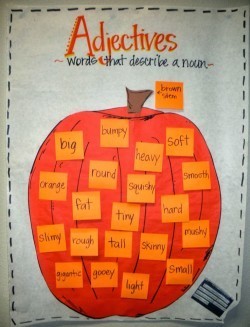

A Few Things About Adjectives

Adjectives are a pretty friendly part of speech; they don’t cause too many problems in our writing. However, there are a couple of things that might cause a question or two: compound adjectives and consecutive adjectives.

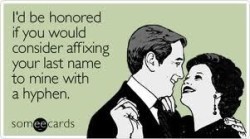

Compound adjectives are just what they sound like—more-than-one-word adjectives. For example, I just made one up that contains four words! And yes, they are hyphenated and sometimes “made up” by the writer.

1. The first thing to know is that these compound adjectives are generally hyphenated when they appear directly before the word they describe, but not if they appear after the word. Here are some examples:

I have a self-published book. BUT My book is self published.

He has a three-year-old son. BUT His son is a three year old.

I am baking an eight-layer-high cake . BUT This cake is eight layers high.

Often, the hyphen (or the elimination of a hyphen) can clear up confusion:

A pink-horned owl is in that tree. (The owl has pink horns. ) Compare that to

A pink horned-owl is in that tree. Now the whole owl is pink. See the difference?

You also want to make sure that the adjective, compound or not, is in the right place:

Two-year-old teacher wanted for new daycare center. (This is a real example! Yes, a very precocious toddler indeed!)

Striped baby’s dress for sale. (Striped dress or striped baby????)

2. By consecutive adjectives, I am referring to two or more adjectives before the same noun. Is there a comma between the adjectives, or isn’t there? Yes. Both.

If one of the adjectives is modifying the other adjective rather than modifying the noun, there is never a comma between them. For example,

bright blue dress (Here, we mean bright blue, not bright dress.)

If the second adjective really goes with the noun, don’t use a comma.

new hit song (Here, hit really goes with song. It is a hit song.)

strict second-grade teacher (second-grade, a compound adjective, really goes with teacher.)

If both of the adjectives are describing the noun, sometimes there is a comma between the two adjectives. The quick way to figure it out is to put and between the two adjectives. If it makes sense to say and between them, you need a comma.

old, torn dress (old and torn dress)

hot, humid day (hot and humid day)

long, narrow hallway (long and narrow hallway)

Happy Halloween and Happy Describing!

October 18, 2013

Dots and Lines: Hyphens, Dashes—and Ellipses . . .

Hyphens, Dashes, Ellips

Hyphens, dashes, and ellipses are less talked about punctuation than, let’s say, commas and semicolons, but they are important to use correctly, nonetheless. And actually many of us use (and overuse) the dots and lines that are dashes and ellipses.

First, let’s talk about hyphens and dashes—the lines. There are three sizes of lines, all different punctuation marks with different uses. Sometimes the problem is the ability to make the different lines on your computer!

- This little one is a hyphen.

–This medium one is an en dash.

—This long one is an em dash.

I have a Mac. The hyphen is on the number line. That one is easy. I made the en dash with Option/Hyphen. I made the em dash (the longest one) by pressing Shift/Option/Hyphen. You can also use Insert Symbol for the long one, and just choose a long line. These symbols, of course, are in the middle of the line. They are not underscores (_). Some people use two hyphens in a row for an em dash. Often (but I could never figure out when), the computer will put them together for you. It results is a short em dash, but it works. We rarely use the en dash, the shorter one, for anything, so generally an en might substitute for an em. However, if your writing is being editing, your editor might fix those dashes to make them proper em dashes.

Hyphen - The hyphen is used to separate words; that is its only function. It separates words that don’t fit on a line. This use becomes more obsolete as computers can fit the type without splitting words at the end of the line. Or, the computer splits the word for you. If you are writing by hand, make sure that words split on the end of the line are split at the syllable break. One-syllable words cannot be split, and proper nouns should not be split either.

Hyphens are also used in some words that have a prefix, where running the whole thing together might be unclear. There may be two vowels in a row, for example.

Example: co-op is different from coop.

However, most words like this are clear and do not need the hyphen: cooperate, reorder, reestablish

Some words with a short prefix still usually use a hyphen: ex-husband

In a word’s evolution, the word often starts out as two separate words (e mail). As the word becomes more common, it is often hyphenated

(e-mail). When the word becomes very common, it often becomes one word (email).

To determine whether of not to hyphenate a word, look it up in the dictionary. If the dictionary gives you a choice, or two dictionaries disagree, choose one way and stick to it. Consistency always give you an air of expertise!

In addition to splitting words with hyphens, you use a hyphen in some compound adjectives, but only if the adjective comes before the noun.

Examples:

I like well-done steak. BUT I like my steak well done.

I have a three-year-old daughter. BUT My daughter is three years old.

Hyphens are also used in the numbers twenty-one to ninety-nine, which are often spelled out; and fractions used as adjectives:

My piggy bank is two-thirds full. BUT I have two thirds of a cake left. (not an adjective here)

En Dash – The en dash is not used very often. It is used as the minus sign in math, and it is used in number ranges. So, you will see it in indexes for sure!

Examples: pages 25–30 OR Jim Jones (1825–1900) was a hero to us all.

Em Dash — The em dash is used (and often overused) to indicate an abrupt change in thought or to emphasize something. If the section to be put within dashes is not a complete sentence, commas can sometimes be used instead (you cannot put a complete sentence in the middle of a sentence and put commas around it; you will have a run on). Parentheses can also be used instead of an em dash, but are far less dramatic!

Examples: I was looking for the cat—I hadn’t seen her in over a week—when I found her in the attic.

My daughter—looking so radiant—got married yesterday.

To make sure you have your dashes in the right place, take out the portion of the sentence within the dashes. The rest of the sentence should be a complete sentence and should make sense on its own without the words that are within the dashes.

Important Note: There are no spaces before or after a hyphen, en dash, or em dash.

Ellipsis . . . The ellipsis is commonly used when something is left out of a quote to make it shorter. Just be careful that you don’t change the meaning of the quote by leaving out selected material. An ellipsis is also used to indicate an unfinished list or unfinished thought at the end of a sentence.

The ellipsis is made with three periods. There is a space before the first period, a space between each of the periods, and a space after the last of the three periods if the ellipsis is in the middle of a sentence or at the end of something that is not a complete sentence. If the ellipsis is used at the end of the sentence, the ending punctuation comes after the three periods. So, if the sentence would end in a period, the ellipsis has four dots instead of three. Another form of punctuation, if necessary, instead of a period, would come after the ellipsis.

Examples:

The mayor said, “There is no reason to increase our taxes in this city . . . would cause the taxpayers great hardship.”

The mayor said, “There is no reason to increase our taxes in this city . . . . (There is more to the speech, but the part given is a complete sentence, so there are four periods.)

She thought to herself, I need to get out of this place because if I don’t . . . (There is no ending period because there is no end to the speaker’s sentence. She is trailing off.)

And this is the end of this blog post . . . .

October 11, 2013

Do I Feel Bad? or Do I Feel Badly?

Bad Versus Badly

Many people are confused about bad versus badly—and for that matter, good versus well. Bad is an adjective; badly is an adverb. Good is an adjective; well is an adverb.

So….do you feel bad or badly? Good or well?

Let’s start a few steps back. Adjectives (one of the parts of speech) are generally used to describe nouns. They tell what kind, which one, or how many.

Examples of adjectives:

pretty dress (what kind?)

bad dream (what kind?)

seven books (how many?)

this tree (which one?)

Adverbs (another part of speech) are generally used to describe verbs. Many times (but not always), adverbs end in -ly and are formed by adding the -ly to an adjective. For example, quick (adjective) and quickly (adverb); soft (adjective) and softly (adverb); and bad (adjective) and badly (adverb). Adverbs tell when, how, and to what extent.

Here are some examples of adverbs in action:

He dances well (how)

He will go soon (when)

He is too thin (to what extent – and an adverb modifying the adjective thin)

Most of the time adjectives are placed before the noun they modify in a sentence. For example,

I have three (adjective) wishes (noun).

I bought the blue (adjective) dress (noun).

However, sometimes adjectives appear away from the noun or pronoun they modify. For example,

The dress is blue.

I am quiet.

Joan is intelligent.

In the above examples, blue describes, or modifies, dress; tired describes I, and intelligent describes Joan.

Now, look at these sentences, which are structured in the same way, but use adverbs instead of adjectives:

Joan speaks intelligently (adverb).

I walk quietly (adverb).

The dress fits perfectly (adverb).

In the above sentencers, the adverbs describe the verbs (as adverbs usually do): speaks how? (intelligently); walk how?(quietly), and fits how? (perfectly).

Now, look at these sentences:

The pizza looks good. (Good is an adjective describing pizza)

The man looks at her carefully. (Carefully is an adverb describing looks.) (Looks how?)

The fabric feels soft. (Soft is an adjective describing fabric.)

The woman feels the fabric lightly. (Lightly is an adverb describing feels.) (Feels how?)

Okay. Let’s explain all this. If you look at the first pair of sentences, with look as the verb, you will discover that there are two kinds of look. In the first sentence, no one is looking at anything. Pizzas don’t have eyes. The looks verb here is not an action verb. Now look at the second pair of sentences. In the first sentence, there is also no action. The fabric has no fingers, and it isn’t feeling anything. However, in the second sentence, the woman is feeling using her fingers.

Some verbs (most verbs) are action words even if they represent mental action (think, consider, wish) rather than physical action. However, some verbs do not represent action. They represent a state of being, emotion, or sense. These verbs are often called linking verbs. Some verbs can be both action and state of being, depending on how they are used in the sentence (feel, taste, sound, and grow, for example).

Linking verbs include the following (not an all-inclusive list):

to be (is, am, are, was, were, will be, has been, have been, etc.)

look

sound

taste

feel

seem

become

grow (The tomatoes are growing quickly – action; I am growing tired – linking)

If this were a math lesson, the linking verb would be an equal sign.

I am tired. I = tired.

Sue is tall. Sue = tall.

The pizza looks good. Pizza = good.

If you try this with an action verb, it doesn’t work:

I play chess. I = chess? No.

She walks the dog. She = dog. No.

Now, what does this all have to do with bad and badly, you ask? After a linking verb, you use an adjective, not an adverb. (The grammatical term for this adjective is predicate adjective). I feel bad is correct bercause feel is a linking verb here. To say I feel badly would imply that feel is being used as an action verb. In other words your fingertips are not working, so you feel badly!

What about I feel good? Or is it I feel well? Grammatically, it is I feel good, since good is the adjective and well is an adverb. However, in this case (yes there is always an exception), you can correctly use well, because well has been accepted to mean a state of good health. So, either way, you are correct.

Now, I feel bad if I have confused you, but I feel good if I have helped to “unconfuse” you!

October 4, 2013

Two, To, Too, Tutu

Most of us know the difference between two, to, and too, but there is some confusion about the correct punctuation with too. Oh, are we really going to talk about tutu too? (No, I’m just pulling your leg warmers!)

Two is obviously the number. No problem there.

To has two uses. First, it can be a preposition. In this case, to is in a phrase and is followed by an article (sometimes) and a noun or pronoun

Example: I went to the mall.

Second, to can be part of an infinitive. In this case, to is followed by a verb.

Example: I want to go with you.

No problem there, although sometimes I do see to used instead of too.

Too also has two uses. First, it can mean also.

Example: I want to go too!

Second, too can mean an excessive amount.

Example: I have too much candy. (Is this even possible?)

It is the first use of too that we are going to talk about in terms of punctuation. Is there a comma before too, or isn’t there?

Which is correct? I want to go, too. OR I want to go too.

There is no real hard and fast rule that makes it incorrect to write it either of those ways. However, there is no reason to put the comma before too. It is preferable to not use a comma.

What about if the too is in the middle of the sentence?

Example: I, too, would like to go.

In this case, especially if the too comes directly after the subject (which it does in the above sentence), the comma is used. Here, the too is used for emphasis, and you would put the commas around it.

A few examples:

I love peanuts, and I love peanut butter too.

We are hiking up that mountain too.

We too are hiking up that mountain. OR We, too, are hiking up that mountain (if you want to emphasize the too).

So, in conclusion — here is one case where there is no real right and wrong. However you don’t need a comma before too at the end of a sentence. If you use too and want to emphasize it, especially right after the subject, go right ahead.

Most of us remember learning to put a comma before too at the end of the sentence. However, not true.

September 27, 2013

Those Pesky Pronouns!

First of all, please excuse a few mistakes I made in last week’s post, which I did eventually correct — after the posts were sent out. I left out the date in September on the opening page of the post. Then, I included an example that was a misplaced modifier. It was a busy week. But no excuse.

Pronouns

Pronouns are one of the eight parts of speech. They are used to stand in for a noun (or another pronoun), and they probably cause more trouble than any other part of speech. There are six varieties of pronouns.

1. Personal Pronouns:

I me my/mine

you you your/yours

he him his

she her hers/her

we us our/ours

they them their/theirs

it it its

who whom whose

The pronouns in the first column are used for subjects in a sentence (nominative case). The ones in the second column are objects (objective case). Those in the last column are possessive (possessive case).

If you took Latin, you might remember these as nominative, accusative, and genitive (I think!)

A. She and I went to the movies.

She and I went to the movies with him and her. (If you have a problem deciding, just take out the other person, and see which sounds right by itself.)

B. It’s between you and me (Not you and I….these pronouns are the objects of the preposition between. You wouldn’t say between we, would you??)

C. Trouble with who and whom? Try substituting he and him. If he works, use who. If him works, use whom.

Who is going with you? (He is going with you.)

Whom are you inviting to the party? (I am inviting him to the party.)

With whom are you going? (I am going with him.)

D. Remember that none of the possessive pronouns (right-hand column) have apostrophes, so its doesn’t either when it implies ownership.

2. Demonstrative Pronouns:

This, that, these, and those — and they don’t usually cause problems. Just remember to use this and that with singulars, and these and those with plurals (not these kind of books, but these kinds of books).

3. Interrogative Pronouns:

Used to ask a question: Who, whom, whose, what, and which – These generally don’t cause a problem.

4. Reflexive/Intensive pronouns:

These are the pronouns with -self at the end: myself, yourself, himself, herself, itself, ourselves, yourselves, themselves

Remember: The only time you can correctly use myself in a sentence is when I is the subject. Likewise, you can use yourself only when you is the subject, and so on.

Correct: I made myself a fancy dinner.

Incorrect: She told a story to him and myself. (should be me)

5. Indefinite Pronouns:

There are many of these including the ones ending in -thing, -one, and -body: Nothing, something, anybody, everything, anyone, etc.

Those are all singular, which leads to a problem! (There are several indefinite pronouns that are plural.)

Everyone is bringing their tents. (Everyone is singular and so is the verb is. But their, which stands in for everyone, is plural. This “mistake” is frequently made because there is no singular pronoun for a human that isn’t gender specific. ”Him or her” is awkward to say. Therefore, it has actually become acceptable to use the singular their. I don’t like it and would recommend just rewriting the sentence to avoid the problem:

Technically incorrect (but acceptable) – Everyone is bringing their tents.

Correct, but awkward – Everyone is bringing his or her tent.

Rewritten to solve the issue – Everyone is bringing a tent.

6. Relative Pronouns:

These pronouns introduce clauses: which, that, who, whom, and whose.

Examples:

This is the boy who lives next door.

That movie, which I saw last year, is now out on DVD.

Just remember to use which and that for things; and who, whose, and whom for people. Also, use commas around the clause if you could take it out and preserve the meaning of the sentence. Use no commas around the clause if you need it to understand the sentence or identify whom or what you are talking about.

For more information on pronouns, you might want to buy my books.  (just a suggestion)

(just a suggestion)