L. Andrew Cooper's Blog, page 7

February 7, 2024

Interview with Filmmaker Michelle Iannantuono: Livescream and Livescreamers

Premieres FREE on YouTube 2/10/24!

Premieres FREE on YouTube 2/10/24!Every day, over 200 loving fans watch Scott Atkinson play horror games online. After a lifetime of failures and false starts, streaming games is the only thing he’s good at. It’s the thing he loves the most. Until it becomes a nightmare. Enter Livescream—a mysterious horror game sent to him by an anonymous fan. At first, he thinks the game is a low-quality indie title. But when his followers start dying one by one, he soon realizes the game is far more sinister. Now, Scott will be forced through nine levels of video game hell, each level representing a different horror game niche, in order to walk away alive. It might just cost him his fans, and his soul, in the process.

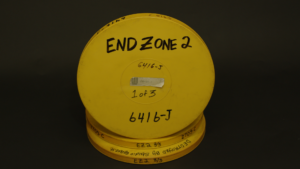

Livescreamers Coming May 2024! Click for the trailer!

Coming May 2024! Click for the trailer!In this sequel to 2020’s Livescream, a popular group of content creators face the ultimate lesson in teamwork when a haunted video game begins killing them one by one.

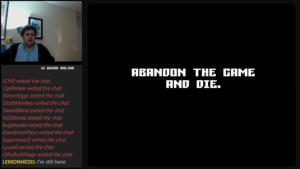

The Interview1. Streamscreen. Livescream mimics a streaming experience, splitting the screen into areas where the audience can see Scott, the game player who talks to his stream’s viewers, in the upper-left corner, his viewers’ text-based commentary in the lower-left corner, and the game Scott is playing on the right. The story unfolds in all three areas and through their interactions. While the form makes sense for the content, the split-screen approach is unusual and got me thinking about films as different as Carrie (1976) and Timecode (2000). What inspired your approach? It seems risky because it demands more from the audience—how does the film manage the audience’s cognitive workload? How do you think managing information from three sources (in three media: video, text, and digital animation) affects the viewers’ responses in terms of fear and horror? How do you think the film’s form plays post-COVID, a time when, thanks to the rise of platforms like Zoom, people are more accustomed to split-screen/multimedia communication interfaces?

MI: It was really important to be aware of “eye tracking” during the editing of Livescream, which is a technique best demonstrated in movies like Mad Max Fury Road. There are a lot of cool video essays and literature about this, but essentially, you want to anticipate where you are pulling the audience’s eye from moment to moment and ensure there is good flow.

Plus, even though the story is divided between chat, gameplay, and Scott, there is only ever one essential thing happening on screen at any given time. In terms of managing horror, it is a way to pull some visual sleight of hand. For instance, most people cite that they never realize Scott gets up and leaves frame, because they’re too busy watching all the viewers leave the chat in that moment. It’s a bit easier to pull off scares in the game when they happen immediately after distracting the audience with the chat.

Finally, it is interesting to think about the impacts of COVID on screenlife, good and bad. On one hand, I feel like the market has been deluged with “in screen” movies, and I have faced some hurdles in marketing the sequel, Livescreamers, post-COVID. I get a lot of comments that no one wants another “Zoom Movie” even though both films are massively more ambitious and stylized than a simple video chat. However, having other comp titles is a bit of a strength. Back during 2018, I had few movies to really compare Livescream to, which made it hard to describe to people.

2. Longstream. Speaking of Livescream’s experimental form, Scott’s video portion of the narrative (with a brief exception) takes place in real time in his corner of the screen as if it were from an uninterrupted run of a webcam. In other words, as a movie unto itself, Scott’s portion might join the “single take” horror/thriller tradition, the most famous member of which is Hitchcock’s Rope (1948), a more recent example of which is Silent House (2011). Both of those movies faked it. Is Scott’s portion an uninterrupted, single take? If so, why was getting that take important enough to go to the trouble, and how much trouble was it? If not, why was the effect important enough to simulate, and how did you pull it off?

MI: It is faked by stitching three takes (again, stitched the two times he exits frame and comes back), although the middle take was a long, uninterrupted 35 minutes. I think this was really important to simulate because we’re supposed to be doing a livestream on Twitch. Those would be uninterrupted and done in real time, inherently.

3. Streaming Countdown. Another horror tradition in which you could position Livescream is the body count film, the slasher or mutations of the slasher such as Saw (2004) that, like Livescream, have victims “dying one by one.” In what ways do and don’t you see Livescream using, and perhaps playing with, slasher conventions? Which do you think are scarier, the glimpses of violence we catch onscreen or the moments of violence we catch by implication? Why?

MI: It is nice to see it recognized as a slasher, as a lot of people miss that. It gets classified more often as tech horror, found footage, screenlife, etc, but at its core, it is a slasher. Scream is one of my favorite horror films, and I always borrow a lot from that movie’s plot progression. You have to cross into Act 2 with a body that the main characters know about. You have to have a consistently dwindling cast, although you also have to have some moments where your characters eke out of a set piece alive – otherwise every set piece becomes a repetitive and suspenseless endeavor where you know they’re doomed.

The limited onscreen violence is mostly a result of budget and format – you just don’t really see your followers’ faces, as a content creator – but I think it worked out for the best. Scott has a moment at the end where he finally sees the faces of the folks he lost, including someone who was a dear friend, and that’s pretty emotionally impactful, I think. Wouldn’t have been the same had you seen the blood spray earlier or known what these guys had looked like. I had to kill one of them on screen in order to sell the idea that the game was actually killing people, but beyond that, the film is deliberately vague.

I’ve lost a lot of internet friends over the years who just kind of vanished from social media or LiveJournal or whatever out of the blue, and I still to this day wonder what happened to them. There is definitely something haunting about not having answers to the fates of your online friends.

4. Screaming Countdown. The diminishing numbers of the living in Livescream are also diminishing numbers of Scott’s followers, and much of the drama and suspense in the film surround Scott’s relationships with those followers, as they are his social lifelines and the keys to the only activity that gives him fulfillment. How does your film reflect on people’s relationships with online personalities and those personalities’ relationships with their followers? How much of the horror comes from the psychological impact of Scott’s crumbling community and the way he diminishes along with his numbers?

MI: Livescream is a rather optimistic look at online community, as I was on the fan side of things at the time. I was inspired by how people found solace and friends within fandoms, rallying around a creator to make connections. Even Scott’s relationship with his mod, JumpingWolf, is an emotional core to reinforce the idea that a follower/creator relationship can be really pure and inspiring, and it doesn’t always have to be a toxic parasocial hellscape.

Part of the horror of losing these followers is because Scott genuinely recognizes and cares about them as people. He is a smaller streamer who is not really depending on this following for income or enterprise. To see them harmed because of his stream is deeply disturbing to him because he has felt like he has a bit of responsibility for his community all this time, creating a safe space for the lonely misfits of the world, and that space becomes immediately unsafe when playing Livescream. Losing this one thing he loves so much is pretty horrific when you realize all this guy wanted was community.

The sequel Livescreamers is a total inversion, showcasing what happens to the relationship between community and creator when it does become a business relationship. When fans equal income, when clout equals better business, and when creators ascend into idols. It was a reflection of my life after years of becoming a creator myself, having my own audience and experiencing invasive dynamics, as well as navigating the waters of asking for money in an ethical way.

5. Streaming Archives. The film we see is (mostly) Scott’s page for streaming his game-playing, which might very well be archived, so it could be an internet artifact we as viewers have stumbled upon—the online equivalent of found footage (if you’ll forgive me—found footage 2.0). In what ways do and don’t you see Livescream using, and perhaps playing with, found footage horror conventions? At least since The Blair Witch Project (1999), found footage films have been tied to internet-supported lore. The seemingly predatory game within Livescream, also called Livescream, may well be the gaming world’s answer to Slenderman. What, if anything, does Livescream have to say about internet artifacts and internet lore?

MI: I always thought it would be fun if MatPat got ahold of the film and broke it down in one of his Game Theory/Film Theory episodes. I suppose that’s really all of it – more than commenting on creepypasta or internet lore directly, the film features some aspects that could have been bait for folks who are into that sort of thing to take and run with. What is the Siren? Why is the game doing this? These are questions that don’t really have good answers – albeit somewhat elucidated in Livescreamers but still not too literally. They’re mostly fun carrots for folks to chew on in a Reddit thread. Borderline ARG, if you will!

For Livescreamers, we also have janusgaming.com which is an “in universe” website for the characters. I post in-character reels on the social media for Janus Gaming too. Just a bit of a fun way to expand the world and let the audience get to know the characters like they’re real humans.

In terms of found footage conventions, I don’t think I borrowed much. For a long time, people thought it had to be Cloverfield or Blair Witch adjacent to be found footage – shaky cam, shot on tape, narrator cameraman. Screenlife was a bit burgeoning in 2018, although The Collingswood Story and Unfriended had broken ground. But in a lot of ways, Livescream and Livescreamers do a lot of new things that no one else has (or had). Livescream is one of the first movies – I think – to incorporate some sort of “chat” element, which is now pretty popular with movies like Spree, Deadstream, Chad Gets the Axe. There aren’t many found footage films that incorporate gaming, sans Deadware. But what all these movies have in common is immense creativity, and that’s really the heart of the genre. If there’s a convention I love about found footage, it’s the constant opportunity to do something innovative.

6. Indie Scream. The game within the film goes through different phases and styles of varying graphical quality. At one point Scott comments on graphics getting an “upgrade,” but he refers to the graphics in general as being “indie,” meaning low-quality. To me, they look like older—let’s say “vintage”—game graphics, and they go well with music (both diegetic and extra-diegetic) with a vintage edge. Why does the game go through different vintage styles, and why did you choose (if you agree with my characterization) a vintage aesthetic? Do you think there’s something scarier about a less sophisticated gaming interface? Why or why not?

MI: Well, that’s low budget for you (lol). I made all the games myself with no experience and with purchased assets. Much like how the webcam format masks the fact that I’m a weak cinematographer, doing it in an indie game aesthetic masked the fact that I was a weak game designer.

But also, most of the games homaged were of similar simplicity and low resolution. There’s a reason I saved Resident Evil for the sequel, and focused on stuff like Slender The Eight Pages, or Five Nights At Freddys for the first Livescream. That being said, I just announced that Livescream is getting a rebuilt remaster later this year, with better looking game design, a 4K and 5.1 mix overhaul, and new graphical design throughout. And it will be an interesting needle to thread, to preserve the “indie” origins of some of the games homaged, while also making the games have far greater visual finesse. I’m already predicting some backlash, funny enough, because some people really dig the lo-fi gutter aesthetic of Livescream’s games! I guess some people do think there’s something creepier about it, even more than the much more polished House of Souls game that the characters play in Livescreamers.

7. Living Hell. The description of Livescream that I cribbed from IMDb describes Scott going through “nine levels of video game hell,” suggesting an extended Dante reference as well as a potential moral dimension, which might become stronger toward the end as continuing to play becomes a deeper and deeper moral quandary. Does Scott go through hell due to some sin or moral imperfection? Does the game Livescream—and/or your film Livescream—have a moral message or mission? If so, what can you say about it without giving too much away? If not, what’s the significance of morality’s absence in a video game hell?

MI: I have always been drawn to Dante’s Inferno – it creeps up in a lot of my work, including stuff that never saw the light of day. Maybe there’s just something sublime about the number 9, as Livescreamers also features nine characters.

But I don’t really think I present the idea that hell = a morally motivated punishment ever. More often I present the idea that hell = any punishment at all, very often unjust or undeserved. Every character I’ve ever put through a sort of hell didn’t really deserve it but was actually oppressed in some way. Leave it to the queer person with no religious background to basically say, “this shit is made up and hell is not fair.”

8. Live Upgrade. With only Scott on the screen for any extended length of time, Livescream feels very intimate despite the reach of its horrors. Livescreamers focuses on a multiplayer gaming experience, leaving out the viewer commentary and instead focusing on a group that inhabits the same physical and digital spaces. What new opportunities for character-driven horror alongside conceptual and visceral scares does this shift in focus open? The graphics are much better—do you feel there’s more of a focus on the digital components? Yes or no, what difference do you think the graphical upgrade makes to your storytelling?

MI: Gunner Willis was a powerhouse solo performance in Livescream, and it also utilized some of my novel writing chops to inspire the audience to connect with characters whom you only ever meet in text. But with only a couple main characters at the core of the story, the emotional arcs are pretty simple. A lot of the entertainment of the film then becomes about “spot the homage!”

Even though Livescreamers is a visual facelift, I actually think the game is less of a focus. The first Livescream is very much a love letter to existing horror games. The chat is drowning in easter eggs. We trade a lot of that winking and homaging in Livescreamers for character and drama instead. The games are set pieces filled with tension, but that tension often comes from shining a light on the flaws of the characters or on good old-fashioned scares. Sure, Livescreamers has its share of borrowed mechanics and familiar aesthetics, but it’s not nearly as much of a fandom parade.

As for multi-player, it was a huge opportunity to work with an ensemble of on-screen actors who you can see, you can hear, and who you can actually see die. I’m really proud of my cast for bringing nine very different humans to life, all of whom represent some form of monster that has been created by the gaming and streaming industry. And hey, it’s less reading for the audience, which I think a lot of folks appreciate.

9. Livescream and Livescream Again! Horror sequels generally up the ante for onscreen action and violence as well as, when mystery with potential for deepening lore is involved, greater development of mystery and lore. At one point a character in Livescreamers refers to ongoing events as “al dente creepypasta.” What are the sequel’s attitudes and—vaguely, without spoilers—contributions to the larger lore of the game and its imperiled players? What can viewers expect in terms of upgrades to the horror’s visibility onscreen?

MI: In terms of upgrades, it is hella gorier and more violent than the first one, including emotional violence. While Livescream touched on the horrors of depression, loneliness, and those who seek purpose in a punishing world, Livescreamers goes even deeper in real world horror, touching on sexual harassment, corporate greed, racism, queerphobia, PTSD, and more.

The larger lore wasn’t really going to be explored, because I just hate when tech horror tries to explain itself too hard. Just slows down the whole movie and ruins disbelief when you have some crone whip out an old Bible and say, “the demon Azazel is now targeting cell phones!” or some shit. I actually was told in an early development note to explain the motive of the game more, and while I took that note a bit to expand upon the rules and motives of “the House” and “the Siren,” I refuse to give any sort of explanation as to where this all began and where it came from. I cannot think of an answer that doesn’t amount of “midichlorians.”

Because ultimately, a rigged game that forces characters against each other is just an allegory for capitalism. Even if you “win” the game, there will be consequences waiting just outside the door – a bigger game you cannot win, no matter how ruthless you are to your equals in the gutter. Scott is an example of someone who is trapped in such a game and can’t really win as a solo person, even with best intentions. The characters of Livescreamers show that if you abandon your peers, you’re similarly doomed. The only real way out is teamwork.

10. Access! How can people learn more about you, view your films, purchase your films, and generally get access to your world (please provide any links you want to share)?

MI: Big things coming to the Octopunk Media channel on YouTube this year (http://youtube.com/octopunkmedia), including the worldwide FREE premiere of Livescream on Saturday 2/10! I am also on Instagram @octopunkmedia, and if you’d like to join our community, you can check out our Discord server https://discordapp.com/invite/evxxwef

About the FilmmakerMichelle Iannantuono is an award-winning writer/director from Charleston, South Carolina. Her previous features include 2018’s Livescream, which was nominated for a Rondo Award and won Best Director at Nightmares Film Festival; 2020’s Detroit Evolution, a queer transformative fan film in the Detroit Become Human video game universe that has surpassed 2 million views on YouTube; and 2023’s Livescreamers, recipient of Best Screenplay at Genreblast and Best Director at NYC Horror Film Festival.

Her previous shorts include “Fame Fatale,” “Seven Deadly Synths,”, and “Detroit Reawakening,” which has half a million views on YouTube. She also produced Michael Smallwood’s “What a Beautiful Wedding,” which screened at FilmQuest, NYC Horror Film Fest, and more.

She is at the helm of Octopunk Media, a media production company with over $25,000 raised for charity to date, a combined 70,000+ worldwide followers, 150+ paying monthly patrons on Patreon, and with fan events hosted in NYC, Munich, Detroit, and London.

The post Interview with Filmmaker Michelle Iannantuono: Livescream and Livescreamers appeared first on L. Andrew Cooper's Horrific Scribblings.

January 31, 2024

Interview with Author Jeff Strand: Demonic, Veiled, It Watches in the Dark (Eek!), and Nightmare in the Backyard (Eek!)

Celebrated author Jeff Strand kindly agreed to answer some questions about his two most recent novels and two more coming soon!

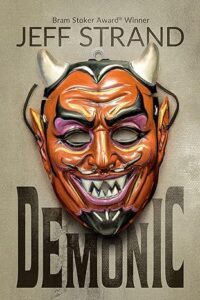

Demonic Click the pic for more!

Click the pic for more!From the Bram Stoker Award-winning author of Pressure and Autumn Bleeds into Winter comes a new novel of unrelenting terror.

Corey is falling in love with his co-worker Quinn. This is a problem. Not only because Quinn is married, but because her husband is a serial killer known as the Toledo Trasher, who has been forcing her to participate in his savage crimes.

With nothing but Quinn’s best interests in mind, Corey shows up at their home with a gun in his pocket and a knife in his hand.

Unfortunately, there are some very dark forces at work, and Corey makes Quinn’s situation worse than he could have ever imagined. And now things are about to get really, really bloody…

With his trademark frenetic pacing and pitch-black humor, Demonic is Jeff Strand at his devilish best.

The first time their eyes lock, it’s an amused and sympathetic look from Alice at the next table. She can tell Nate’s blind date is going horribly awry.

The second time is a chance meeting at a grocery store. Or is it by chance? It’s a little weird, but either way, Nate and Alice hit it off immediately.

He really likes her. They have great chemistry. But there’s something a little off—okay, a lot off—about her. Not just the unexplained sadness. It’s an intense desire, almost a desperation, for things to move much faster than Nate is comfortable with.

Alice has an obvious secret. What’s she hiding?

When Nate finds out…well, nobody said this was a romantic comedy…

From the Bram Stoker Award-winning author of My Pretties and Autumn Bleeds into Winter comes… Veiled.

It Watches in the Dark (Eek!) Available April 2, 2024! Pre-order the hardcover now!

Available April 2, 2024! Pre-order the hardcover now!“She glanced over her shoulder. Had the scarecrow moved? It stood there, smile stitched on its face, but now it felt like a smirk.”

Prepare to be scared silly in this creepy middle-grade novel! Twins seek medical help in a remote village after their father is in a canoeing accident… only to discover the scarecrow that stands watch in town may have a stronger hold over the residents than expected. Perfect for fans of R.L. Stine, Dan Poblocki, and Mary Downing Hahn.

Twins Oliver and Trisha love going on adventures with their dad. Canoeing and camping on the Champion River will be their best trip yet! But when they capsize in rapids, their father is knocked unconscious. Alone and without cell phone reception, their only choice is to continue down river for help.

Hours of paddling brings them to an old dock, and a narrow path leads them to a small village. The townspeople are kind and helpful but strangely focused on the giant scarecrow in the village square. “He watches over us,” the twins are told in whispers. “He keeps us safe.”

An old woman warns the twins not to spend the night in the village. Not if they ever want to leave. But with the sun soon to set and their father not well enough to be moved, how can they escape? More importantly, can they survive?

Nightmare in the Backyard (Eek!) Available August 6, 2024! Pre-order the hardcover now!

Available August 6, 2024! Pre-order the hardcover now!When the scratching starts on the tent, a backyard camping trip turns terrifying for three friends. Prepare to be scared silly in this creepy middle-grade novel for fans of R.L. Stine, Dan Poblocki, and Mary Downing Hahn.

Chloe, Avery, and Madison can’t wait to spend the night camping in the backyard. Smores! Spooky stories! Trading secrets! It’s going to be awesome. Sure, Elijah the kid next door keeps trying to prank them, but it’s all in good fun. Who doesn’t like a little scare after the sun has set and the moonlight casts creepy shadows everywhere?

Then the scratching starts on the tent fabric. The girls think it must be Elijah again, but there’s no one outside. As the scratching gets more insistent, the girls may need to start asking WHAT is making that noise rather than WHO. Can they make it through the night?

The Interview1. Speed Demon. The description of Demonic refers to your “trademark frenetic pacing.” I’m still learning about your trademarks, but Demonic’s breakneck narrative speed is definitely a standout quality: it starts on a roll, gets faster, and never slows down. How do you plan a story so that the action and horror will proceed with nary a pause? How do you manage characterization while the characters can hardly catch their breaths? “Pitch-black humor” is another trademark, and aspects of Demonic are indeed quite funny. Where does the humor come from, and how do humor and pacing relate?

JS: The pacing doesn’t require that much planning ahead, beyond coming up with a concept that will sustain it. I worked out the big turning points of Demonic, and I knew I could tell the story without any padding. I try to maintain a fast pace even in something like Veiled, which is a psychological thriller without a lot of action.

Characterization is always my primary focus. The goal is to create compelling characters very quickly, but also never to lose sight of their personalities when the action kicks in. There’s an extended car chase in Demonic, but it’s Corey and Quinn in the vehicle, not some 1980’s video game characters, and how they’re reacting to the situation is what’s important. Corey has never experienced anything like this. He works a desk job. Corey and Quinn’s relationship is in a very weird place at the moment. That’s all key to the scene, though, obviously, I also want the reader to think “Woooo-eeeeee, that was a kick-ass car chase!”

For me, the humor is usually instinctual. I write humor pretty naturally, so if it’s a novel like Demonic, I’m not thinking, “Okay, I need a good joke here.” (Unlike, say, my novelization of Attack of the Killer Tomatoes, where the whole point was to be funny.) I allow myself quite a bit of creative license, but I do try to keep the humor believable within the context of the story.

2. Demon Theory. I don’t think I’m spoiling anything by saying that conflicts involving forces one might describe as “demonic” occur in Demonic, but they seem very different from Exorcist-style battles between the forces of Heaven and Hell. How would you describe the demonic in this novel’s universe? What, if any, religious context might it have? What makes this version of the demonic scary?

JS: Without giving too much away, they’re humans who have pledged their loyalty to somebody very bad, and this loyalty comes with certain benefits. There’s not much in the way of religious context—there aren’t any Bible passages quoted in the book. You’re not going to close the book and question your existing worldview. They’re scary because, as our heroes discover early on, they don’t exactly die the way a normal person would.

3. Demon Hunter? Corey, Demonic’s protagonist, fumbles his way into the main plot, and he does a few things that are remarkably heroic yet (forgive me) remarkably stupid. How would you describe Corey, and why did you design your protagonist this way? How sympathetic do you think readers generally feel toward him? Do you feel his character says something about “regular” guys? Why or why not?

JS: Flawed heroes are a recurring theme in my work, and it’s always a tricky balancing act. Unless it’s in something like Bang Up, purely for comedic effect, I don’t want to write about characters who are stupid. Corey isn’t an idiot. He’s just in waaaayyyyy over his head, and not every decision he makes is the best one. My goal is always to show things from the character’s perspective and have the reader think, “Okay, that worked out badly, but I might have done the same thing.”

You’re supposed to be rooting for the guy, and based on the reviews, I think readers do. I assume that most “regular” guys accept that if they were in this kind of mess, they might not handle it like Jack Reacher. I’m an intelligent guy who is extremely savvy about online scams, but not too long ago one of them got me and I clicked a link that subscribed me to several hundred mailing lists. Hopefully that didn’t make me too dumb to live!

4. Femmes Fatales. Quinn in Demonic and Alice in Veiled both know a lot more than they initially share with their male co-stars and, at least partly through their feminine allure, get the guys involved in overwhelmingly dangerous situations. They’re not noir stereotypes, but they do seem like femmes fatales. Do you see them that way? What might be the consequences of seeing either character through such a lens? Alice’s situation, not revealed until halfway through the book and developing until the end, makes her character particularly problematic, so I’ll repeat what I asked about Corey: how sympathetic do you think readers generally feel toward her?

JS: I don’t really see Quinn that way. She’s not manipulative and wasn’t trying to pull Corey into this situation. She had too much to drink and told him more than she should have, and he took the initiative to try to solve her problem without telling her. He got himself into this mess and made things much worse for her.

Obviously, Alice is difficult to discuss without spoilers, but the question is “How far would you go?” Because much of the plot of Veiled is a closely guarded secret and reviewers have (mostly) been considerate about not blabbing the details, I haven’t received much feedback on that aspect, but I have heard from readers who told me they can relate and would do the same thing. But if a reader hates her, that’s also a valid response, and I don’t think it takes away from the experience!

5. At Home with the Range. Your bio says your novels are “all over the place,” and I get a taste of that moving from Demonic, which focuses on fast action and explicit horror, to Veiled, which focuses on suspense, subtler, grounded horror, and so much mystery that asking questions about it without revealing too much is challenging. How and when do you determine which genre conventions, moods, and styles will govern a project? Do you deliberately change focuses as you move from one project to the next?

JS: Very deliberately. I don’t want to write the same book over and over. When I go really, really dark, as with My Pretties or Bring Her Back, I try to follow it up with something more fun. If my last book was supernatural horror, I might try a thriller. Every once in a while, I’ll do a complete outlier like Kumquat, a romantic comedy. Within the very important context that writing is my only source of income and I have to write stuff that my readers want to buy, I try to mix things up.

6. Veiled Inspiration? A couple of familiar nightmares seem to lie in Veiled’s foundation. The first, mentioned in the description, is the girlfriend who wants too much commitment too soon. The second—hopefully not too much of a spoiler—is saying something insensitive in the wrong company and having it come back to haunt you. Did first- or second-hand experiences with such nightmares inspire you? Where did (what you can share about) Veiled originate?

JS: Veiled originated with that great big reveal at the halfway point. It wasn’t going to be a secret; it was simply going to be the plot of the book. But when I began to construct the story, I realized that it would be more effective if the reader didn’t know what was happening, and so I reworked it as a mystery.

I haven’t had any experience with girlfriends who want too much commitment too soon, but I also haven’t had any experience with werewolves, so I was able to fake it. As for saying the wrong thing… I’m still haunted by stuff I said thirty years ago to people who probably forgot it thirty seconds later. In my non-fiction book The Writing Life: Reflections, Recollections, and a Lot of Cursing, I wrote about an event where a woman came up to my table to rave about how much she loved Cyclops Road. We talked for a couple of minutes, and then a friend I’d never met in real life came up behind me to introduce herself. My attention was pulled away with a quick “Hey, great to finally meet you!” and when I turned back, the woman was gone, never to be seen again. She probably thought I was a complete douchebag. It makes me sick to think about that moment, but what if she obsessed over it even more…?

7. Childhood Inspiration. More than once, Corey in Demonic retreats into happy childhood memories of the Scholastic Book Fair to escape the horrors around him. I get the feeling you might have similar memories (I certainly do). Now you write middle-grade novels that might be the stuff of such memories for a new generation. Does enabling those kinds of experiences motivate your middle-grade writing? What inspired you to target younger readers with It Watches in the Dark and Nightmare in the Backyard, both of which are forthcoming later in 2024?

JS: Though I do think “Okay, how would I have reacted to this situation at this age?” there’s almost none of my personal experience in either of these books. I just try to create characters and have them behave in a believable manner. I keep the slang and pop culture references to a bare minimum because that kind of stuff can become hilariously out of date very quickly. The inspiration for writing these came from my editor at Sourcebooks saying, “Hey, you wrote a few YA comedies for us, would you now like to write some middle-grade horror novels?”

The inspiration for the specific books was from my frequent process of asking, “What horror trope haven’t I tackled yet, and how can I twist it around?” In this case it was folk horror and Lovecraftian horror.

8. Eek! Maybe I’m just sensitive to the idea of being trapped overnight in a small village that seems to be controlled by an evil scarecrow, but It Watches in the Dark sounds freaky to me, and I’m a hardcore horrorhound. Is it as scary as it sounds? How do you measure out the fright factor to make the level appropriate for middle grade? How do you feel about giving kids nightmares?

JS: It’s even scarier than it sounds. You definitely can’t handle it. But seriously, it’s really just about walking the line between “fun creepy” and “disturbing creepy.” I want it to live up to the promise of a book that has a great big scarecrow on the cover, but my goal is not for the kids to close the book and stare off blankly, their fragile minds coping with the nihilism of existence. It’s the scariness of a campfire story or a rollercoaster. (Admittedly, my editor did ask me to tone down some bits that went a little too far.) If a kid has to sleep with the lights on for a couple of nights, that’s part of the fun of being a horror fan. There’s no bait and switch–the hope is that a kid who picks up a book with that cover is looking for that kind of reading experience!

9. Backyard Universe. I remember the backyard being a place to build worlds in my imagination, but home was always nearby for a quick escape. In Nightmare in the Backyard, how do you transform the girls’ backyard camping excursion into a universe remote enough for help to seem out of range and the dangers to seem life-threatening?

JS: A big part of their problem in the book is that their cell phones don’t work, and nobody in the neighboring yards can seem to see or hear what is happening. Chloe’s mother is right there inside the house, but she has no idea what’s going on! They aren’t in a cabin deep in the woods, but they might as well be.

10. Maddening. Your bio says several of your books are in development as motion pictures, and you’re MOSTLY not allowed to blab any details. I’m seizing on that “mostly” and asking—what details CAN you share? Which books? Can you say anything about timelines? Are you involved with the screenwriting? Your writing is very visual and could translate well to the screen. Exciting stuff!

JS: There’s a lot of stuff going on, but I’ve found the idea of “Don’t ask how a bad movie got made; ask how anything gets made at all!” to be entirely true. It’s unreal. I’ll just go ahead and bombard you with a list of titles that are in some stage of development: I Have a Bad Feeling About This, Wolf Hunt, Clowns Vs. Spiders, Allison, A Bad Day For Voodoo, Kutter, The Greatest Zombie Movie Ever, Kumquat, An Apocalypse of Our Own, and The Odds. For some of these I wrote the screenplay; for most I didn’t. Some have been in the works for several years. One is a big-studio production that earned me my WGA card for writing the script. None of them have yet involved somebody turning on a camera to record a moving image.

About the Author

About the Author

Jeff Strand’s bio was funnier when he talked about losing the Bram Stoker Award four times, but he’s now a Bram Stoker Award WINNER!

His novels are usually classified as horror, but they’re really all over the place, almost always with a great big dose of humor. He’s written five young adult novels that all fall into the “really goofy comedy” category.

Several of his books are in development as motion pictures, and he’s mostly not allowed to blab any details, which he finds MADDENING.

He currently lives in sunny, warm Duluth, Minnesota.

The post Interview with Author Jeff Strand: Demonic, Veiled, It Watches in the Dark (Eek!), and Nightmare in the Backyard (Eek!) appeared first on L. Andrew Cooper's Horrific Scribblings.

Interview with Author Jeff Strand: Demonic, Veiled, It Watches in the Dark (Eek!), and Nightmare in the Back Yard (Eek!)

Celebrated author Jeff Strand kindly agreed to answer some questions about his two most recent novels and two more coming soon!

Demonic Click the pic for more!

Click the pic for more!From the Bram Stoker Award-winning author of Pressure and Autumn Bleeds into Winter comes a new novel of unrelenting terror.

Corey is falling in love with his co-worker Quinn. This is a problem. Not only because Quinn is married, but because her husband is a serial killer known as the Toledo Trasher, who has been forcing her to participate in his savage crimes.

With nothing but Quinn’s best interests in mind, Corey shows up at their home with a gun in his pocket and a knife in his hand.

Unfortunately, there are some very dark forces at work, and Corey makes Quinn’s situation worse than he could have ever imagined. And now things are about to get really, really bloody…

With his trademark frenetic pacing and pitch-black humor, Demonic is Jeff Strand at his devilish best.

The first time their eyes lock, it’s an amused and sympathetic look from Alice at the next table. She can tell Nate’s blind date is going horribly awry.

The second time is a chance meeting at a grocery store. Or is it by chance? It’s a little weird, but either way, Nate and Alice hit it off immediately.

He really likes her. They have great chemistry. But there’s something a little off—okay, a lot off—about her. Not just the unexplained sadness. It’s an intense desire, almost a desperation, for things to move much faster than Nate is comfortable with.

Alice has an obvious secret. What’s she hiding?

When Nate finds out…well, nobody said this was a romantic comedy…

From the Bram Stoker Award-winning author of My Pretties and Autumn Bleeds into Winter comes… Veiled.

It Watches in the Dark (Eek!) Available April 2, 2024! Pre-order the hardcover now!

Available April 2, 2024! Pre-order the hardcover now!“She glanced over her shoulder. Had the scarecrow moved? It stood there, smile stitched on its face, but now it felt like a smirk.”

Prepare to be scared silly in this creepy middle-grade novel! Twins seek medical help in a remote village after their father is in a canoeing accident… only to discover the scarecrow that stands watch in town may have a stronger hold over the residents than expected. Perfect for fans of R.L. Stine, Dan Poblocki, and Mary Downing Hahn.

Twins Oliver and Trisha love going on adventures with their dad. Canoeing and camping on the Champion River will be their best trip yet! But when they capsize in rapids, their father is knocked unconscious. Alone and without cell phone reception, their only choice is to continue down river for help.

Hours of paddling brings them to an old dock, and a narrow path leads them to a small village. The townspeople are kind and helpful but strangely focused on the giant scarecrow in the village square. “He watches over us,” the twins are told in whispers. “He keeps us safe.”

An old woman warns the twins not to spend the night in the village. Not if they ever want to leave. But with the sun soon to set and their father not well enough to be moved, how can they escape? More importantly, can they survive?

Nightmare in the Backyard (Eek!) Available August 6, 2024! Pre-order the hardcover now!

Available August 6, 2024! Pre-order the hardcover now!When the scratching starts on the tent, a backyard camping trip turns terrifying for three friends. Prepare to be scared silly in this creepy middle-grade novel for fans of R.L. Stine, Dan Poblocki, and Mary Downing Hahn.

Chloe, Avery, and Madison can’t wait to spend the night camping in the backyard. Smores! Spooky stories! Trading secrets! It’s going to be awesome. Sure, Elijah the kid next door keeps trying to prank them, but it’s all in good fun. Who doesn’t like a little scare after the sun has set and the moonlight casts creepy shadows everywhere?

Then the scratching starts on the tent fabric. The girls think it must be Elijah again, but there’s no one outside. As the scratching gets more insistent, the girls may need to start asking WHAT is making that noise rather than WHO. Can they make it through the night?

The Interview1. Speed Demon. The description of Demonic refers to your “trademark frenetic pacing.” I’m still learning about your trademarks, but Demonic’s breakneck narrative speed is definitely a standout quality: it starts on a roll, gets faster, and never slows down. How do you plan a story so that the action and horror will proceed with nary a pause? How do you manage characterization while the characters can hardly catch their breaths? “Pitch-black humor” is another trademark, and aspects of Demonic are indeed quite funny. Where does the humor come from, and how do humor and pacing relate?

JS: The pacing doesn’t require that much planning ahead, beyond coming up with a concept that will sustain it. I worked out the big turning points of Demonic, and I knew I could tell the story without any padding. I try to maintain a fast pace even in something like Veiled, which is a psychological thriller without a lot of action.

Characterization is always my primary focus. The goal is to create compelling characters very quickly, but also never to lose sight of their personalities when the action kicks in. There’s an extended car chase in Demonic, but it’s Corey and Quinn in the vehicle, not some 1980’s video game characters, and how they’re reacting to the situation is what’s important. Corey has never experienced anything like this. He works a desk job. Corey and Quinn’s relationship is in a very weird place at the moment. That’s all key to the scene, though, obviously, I also want the reader to think “Woooo-eeeeee, that was a kick-ass car chase!”

For me, the humor is usually instinctual. I write humor pretty naturally, so if it’s a novel like Demonic, I’m not thinking, “Okay, I need a good joke here.” (Unlike, say, my novelization of Attack of the Killer Tomatoes, where the whole point was to be funny.) I allow myself quite a bit of creative license, but I do try to keep the humor believable within the context of the story.

2. Demon Theory. I don’t think I’m spoiling anything by saying that conflicts involving forces one might describe as “demonic” occur in Demonic, but they seem very different from Exorcist-style battles between the forces of Heaven and Hell. How would you describe the demonic in this novel’s universe? What, if any, religious context might it have? What makes this version of the demonic scary?

JS: Without giving too much away, they’re humans who have pledged their loyalty to somebody very bad, and this loyalty comes with certain benefits. There’s not much in the way of religious context—there aren’t any Bible passages quoted in the book. You’re not going to close the book and question your existing worldview. They’re scary because, as our heroes discover early on, they don’t exactly die the way a normal person would.

3. Demon Hunter? Corey, Demonic’s protagonist, fumbles his way into the main plot, and he does a few things that are remarkably heroic yet (forgive me) remarkably stupid. How would you describe Corey, and why did you design your protagonist this way? How sympathetic do you think readers generally feel toward him? Do you feel his character says something about “regular” guys? Why or why not?

JS: Flawed heroes are a recurring theme in my work, and it’s always a tricky balancing act. Unless it’s in something like Bang Up, purely for comedic effect, I don’t want to write about characters who are stupid. Corey isn’t an idiot. He’s just in waaaayyyyy over his head, and not every decision he makes is the best one. My goal is always to show things from the character’s perspective and have the reader think, “Okay, that worked out badly, but I might have done the same thing.”

You’re supposed to be rooting for the guy, and based on the reviews, I think readers do. I assume that most “regular” guys accept that if they were in this kind of mess, they might not handle it like Jack Reacher. I’m an intelligent guy who is extremely savvy about online scams, but not too long ago one of them got me and I clicked a link that subscribed me to several hundred mailing lists. Hopefully that didn’t make me too dumb to live!

4. Femmes Fatales. Quinn in Demonic and Alice in Veiled both know a lot more than they initially share with their male co-stars and, at least partly through their feminine allure, get the guys involved in overwhelmingly dangerous situations. They’re not noir stereotypes, but they do seem like femmes fatales. Do you see them that way? What might be the consequences of seeing either character through such a lens? Alice’s situation, not revealed until halfway through the book and developing until the end, makes her character particularly problematic, so I’ll repeat what I asked about Corey: how sympathetic do you think readers generally feel toward her?

JS: I don’t really see Quinn that way. She’s not manipulative and wasn’t trying to pull Corey into this situation. She had too much to drink and told him more than she should have, and he took the initiative to try to solve her problem without telling her. He got himself into this mess and made things much worse for her.

Obviously, Alice is difficult to discuss without spoilers, but the question is “How far would you go?” Because much of the plot of Veiled is a closely guarded secret and reviewers have (mostly) been considerate about not blabbing the details, I haven’t received much feedback on that aspect, but I have heard from readers who told me they can relate and would do the same thing. But if a reader hates her, that’s also a valid response, and I don’t think it takes away from the experience!

5. At Home with the Range. Your bio says your novels are “all over the place,” and I get a taste of that moving from Demonic, which focuses on fast action and explicit horror, to Veiled, which focuses on suspense, subtler, grounded horror, and so much mystery that asking questions about it without revealing too much is challenging. How and when do you determine which genre conventions, moods, and styles will govern a project? Do you deliberately change focuses as you move from one project to the next?

JS: Very deliberately. I don’t want to write the same book over and over. When I go really, really dark, as with My Pretties or Bring Her Back, I try to follow it up with something more fun. If my last book was supernatural horror, I might try a thriller. Every once in a while, I’ll do a complete outlier like Kumquat, a romantic comedy. Within the very important context that writing is my only source of income and I have to write stuff that my readers want to buy, I try to mix things up.

6. Veiled Inspiration? A couple of familiar nightmares seem to lie in Veiled’s foundation. The first, mentioned in the description, is the girlfriend who wants too much commitment too soon. The second—hopefully not too much of a spoiler—is saying something insensitive in the wrong company and having it come back to haunt you. Did first- or second-hand experiences with such nightmares inspire you? Where did (what you can share about) Veiled originate?

JS: Veiled originated with that great big reveal at the halfway point. It wasn’t going to be a secret; it was simply going to be the plot of the book. But when I began to construct the story, I realized that it would be more effective if the reader didn’t know what was happening, and so I reworked it as a mystery.

I haven’t had any experience with girlfriends who want too much commitment too soon, but I also haven’t had any experience with werewolves, so I was able to fake it. As for saying the wrong thing… I’m still haunted by stuff I said thirty years ago to people who probably forgot it thirty seconds later. In my non-fiction book The Writing Life: Reflections, Recollections, and a Lot of Cursing, I wrote about an event where a woman came up to my table to rave about how much she loved Cyclops Road. We talked for a couple of minutes, and then a friend I’d never met in real life came up behind me to introduce herself. My attention was pulled away with a quick “Hey, great to finally meet you!” and when I turned back, the woman was gone, never to be seen again. She probably thought I was a complete douchebag. It makes me sick to think about that moment, but what if she obsessed over it even more…?

7. Childhood Inspiration. More than once, Corey in Demonic retreats into happy childhood memories of the Scholastic Book Fair to escape the horrors around him. I get the feeling you might have similar memories (I certainly do). Now you write middle-grade novels that might be the stuff of such memories for a new generation. Does enabling those kinds of experiences motivate your middle-grade writing? What inspired you to target younger readers with It Watches in the Dark and Nightmare in the Backyard, both of which are forthcoming later in 2024?

JS: Though I do think “Okay, how would I have reacted to this situation at this age?” there’s almost none of my personal experience in either of these books. I just try to create characters and have them behave in a believable manner. I keep the slang and pop culture references to a bare minimum because that kind of stuff can become hilariously out of date very quickly. The inspiration for writing these came from my editor at Sourcebooks saying, “Hey, you wrote a few YA comedies for us, would you now like to write some middle-grade horror novels?”

The inspiration for the specific books was from my frequent process of asking, “What horror trope haven’t I tackled yet, and how can I twist it around?” In this case it was folk horror and Lovecraftian horror.

8. Eek! Maybe I’m just sensitive to the idea of being trapped overnight in a small village that seems to be controlled by an evil scarecrow, but It Watches in the Dark sounds freaky to me, and I’m a hardcore horrorhound. Is it as scary as it sounds? How do you measure out the fright factor to make the level appropriate for middle grade? How do you feel about giving kids nightmares?

JS: It’s even scarier than it sounds. You definitely can’t handle it. But seriously, it’s really just about walking the line between “fun creepy” and “disturbing creepy.” I want it to live up to the promise of a book that has a great big scarecrow on the cover, but my goal is not for the kids to close the book and stare off blankly, their fragile minds coping with the nihilism of existence. It’s the scariness of a campfire story or a rollercoaster. (Admittedly, my editor did ask me to tone down some bits that went a little too far.) If a kid has to sleep with the lights on for a couple of nights, that’s part of the fun of being a horror fan. There’s no bait and switch–the hope is that a kid who picks up a book with that cover is looking for that kind of reading experience!

9. Backyard Universe. I remember the backyard being a place to build worlds in my imagination, but home was always nearby for a quick escape. In Nightmare in the Backyard, how do you transform the girls’ backyard camping excursion into a universe remote enough for help to seem out of range and the dangers to seem life-threatening?

JS: A big part of their problem in the book is that their cell phones don’t work, and nobody in the neighboring yards can seem to see or hear what is happening. Chloe’s mother is right there inside the house, but she has no idea what’s going on! They aren’t in a cabin deep in the woods, but they might as well be.

10. Maddening. Your bio says several of your books are in development as motion pictures, and you’re MOSTLY not allowed to blab any details. I’m seizing on that “mostly” and asking—what details CAN you share? Which books? Can you say anything about timelines? Are you involved with the screenwriting? Your writing is very visual and could translate well to the screen. Exciting stuff!

JS: There’s a lot of stuff going on, but I’ve found the idea of “Don’t ask how a bad movie got made; ask how anything gets made at all!” to be entirely true. It’s unreal. I’ll just go ahead and bombard you with a list of titles that are in some stage of development: I Have a Bad Feeling About This, Wolf Hunt, Clowns Vs. Spiders, Allison, A Bad Day For Voodoo, Kutter, The Greatest Zombie Movie Ever, Kumquat, An Apocalypse of Our Own, and The Odds. For some of these I wrote the screenplay; for most I didn’t. Some have been in the works for several years. One is a big-studio production that earned me my WGA card for writing the script. None of them have yet involved somebody turning on a camera to record a moving image.

About the Author

About the Author

Jeff Strand’s bio was funnier when he talked about losing the Bram Stoker Award four times, but he’s now a Bram Stoker Award WINNER!

His novels are usually classified as horror, but they’re really all over the place, almost always with a great big dose of humor. He’s written five young adult novels that all fall into the “really goofy comedy” category.

Several of his books are in development as motion pictures, and he’s mostly not allowed to blab any details, which he finds MADDENING.

He currently lives in sunny, warm Duluth, Minnesota.

The post Interview with Author Jeff Strand: Demonic, Veiled, It Watches in the Dark (Eek!), and Nightmare in the Back Yard (Eek!) appeared first on L. Andrew Cooper's Horrific Scribblings.

January 24, 2024

Interview with Author Ryan Harding: Transcendental Mutilation

Hardcore horror writer and pioneer of body horror in print Ryan Harding is here to discuss his new collection of short stories, Transcendental Mutilation, a collection of tales interconnected on several levels.

Transcendental Mutilation Click the pic for more!

Click the pic for more!SIGILS INCISED, A COMMUNION WITH THE BLADE. A trio of young people stranded on an uncharted island discovers its sickening secrets. A man contracts a degenerative disease through a webcam encounter. An office worker follows the object of his affection into a mysterious club where life, death, and anatomy have no limits. A reforming necrophiliac struggles to maintain the illusion of normalcy in a new relationship. A woman awakens with other captives in the basement of a madman using them to attract impossible prey.

UNLOCK THE GATES OF FLESH, WORLDS WITHIN FLAYED. A decade after the infamous Genital Grinder, Ryan Harding returns with ten more stories, collected for the first time— including the Splatterpunk Award-winning tales “The Seacretor” and “Angelbait”— which plunder the depths of depravity and obsession, yielding offenses and transformations of the flesh never before seen or carved. His first solo work in years dissects its themes and characters alike in a sublime autopsy worthy of the hardcore horror pantheon. Even the vomitorium has its philosophy, and the keys to revelation are all serrated.

EVERY JOURNEY BEGINS WITH A SINGLE SLICE… TRANSCENDENTAL MUTILATION

The Interview1. Transcendental Details. In your “Prelude to Repulsion” at the beginning of Transcendental Mutilation, you mention that stories in the book link to each other as well as to your other works, and indeed, references to Sarah Putnam, Geisha Hammond, the Woodsman, and Agent Orange recur, places such as Morgan, Sandalwood, and Iona come up repeatedly, and the character Kendall appears more than once. Tell us more about your interconnected universe (or, if it’s a multiverse, your multiverse). Which details tend to reappear and why? What do they add to the stories and to readers’ experiences? Without giving too much away, what elements from Transcendental Mutilation might readers expect to see again?

RH: This is something I started in Genital Grinder. That interconnectedness resonated with me in a collection like Bret Easton Ellis’s The Informers. It adds another layer, turning it into its own world with a recurring cast, hopefully investing readers that much more in what’s going on. As stories like “Final Indications” (in GG) and “Last Time at Thanksgiving” (in Transcendental Mutilation) threaten something more apocalyptic, I suppose they function more like resets, although there are recurring threads from GG in TM, and characters and ideas from TM could also manifest in other stories or books one day. The Woodsman is something I’ve thought about revisiting, for instance, and I keep threatening to continue the misadventures of Von and Greg from GG.

2. Transitory Bodies. Aside from his involvement in the plot of “Orificially Compromised,” who is “Dr. Braedon Obrist,” and what is “Transitory Bodies?” Why have you added a quotation from this work to each tale? Do the quotations point toward a larger, coherent philosophy behind Transcendental Mutilation? If so, would you please—in brief—explain the core of that philosophy?

RH: Dr. Braedon Obrist is sort of like TM’s answer to Brian O’Blivion from Videodrome—a philosopher for a world influenced by technology in ways both physical and metaphysical. You only get so much insight into his views in “Orifically Compromised,” so I thought it would be interesting to use excerpts from his Transitory Bodies book as epigraphs. I imagine TB to be a collection of essays where he explores existential questions proposed by the changing nature of our psyches with technology and the imminent threat of InterphaZ. I just sat down one day and wrote them all, and I liked how they came out. The excerpts obliquely lay out themes for each story. If there is a coherent philosophy, it is the idea that the modern world is altering us in ways we haven’t seen before, connecting us more but also enhancing our individual alienation. We’re patient zeros of a technological and resulting metaphysical virus. The characters in TM are often transformed by that virus or willing to alter themselves, sometimes as an escape, other times as an assimilation. In stories where technology fails, there tends to be something older and darker lurking.

3. Long Live…. “InterphaZ,” mentioned in several stories, especially “Orificially Compromised,” seems right at home with David Cronenberg’s Videodrome and eXistenZ, and since you contributed “Orificially Compromised” to the collection The New Flesh: A Literary Tribute to David Cronenberg, I’m guessing that’s no coincidence (you also praise Cronenberg extensively in your postscript to Transcendental Mutilation). What is InterphaZ, and how specifically does it relate to or reflect on Cronenberg’s creations? More broadly, how have Cronenberg and other filmmakers influenced your writing? What, if anything, is cinematic about your style?

RH: InterphaZ is a mega corporation furthering technology and the subtle (and not so subtle) mutation of its customers. I think it’s a more cynical interpretation of some of the organizations from Cronenberg’s films, slowly recreating the world in its preferred image. In “Orificially Compromised,” doctors must be approved for any treatment pertaining to an InterphaZ product. That only seems barely absurd these days. They also play a role in mind control technology in a novella I wrote called The Profile, part of the Call Me Hoop anthology. I love David Cronenberg, and his body horror films had a major impact on me. It’s something we all have to confront if we live long enough. Our bodies will change and ultimately fail us. It’s a more visceral metaphor for the dying process. I believe graphic horror is especially the province of horror films, where gore in splatter movies like Dawn of the Dead preceded the works of Clive Barker and the Splatterpunks in the 80s. Extreme horror is often like elaborate special FX work, e.g., the exploding head in Scanners, the transformations in Videodrome, The Thing, etc., and the carnage of Italian horror like Fulci, Argento, etc.I try to be as descriptive as I can with those sequences, although ideally they will feel more like something readers are experiencing than merely witnessing.

4. Genital Mutilation. The title of your previous collection, Genital Grinder, seems to warn of this motif: you write about violent damage to or transformation of genitalia in quite a few tales in Transcendental Mutilation. What’s your attraction to this region of repulsion? What do you think attracts readers to genital chaos (I squirmed but couldn’t stop reading)? Except when characters enjoy it (and they usually don’t), do you see genital mutilations as punishments for wayward desires? Why or why not?

RH: That was something tabooer when I began writing my hardcore stories. I mentioned how splatter was prevalent in horror movies, but anything genital related was scarce compared to eviscerations or head explosions. I would say disembowelment was the ultimate splatter effect (anything involving genitals was quick to hit the cutting room floor to avoid an X rating), but the rarity and intimacy of a scene like the castration in Make Them Die Slowly could make an indelible impression, too. In 1999, I read Edward Lee and John Pelan’s Shifters, which includes this excruciating moment with a woman and a pizza cutter. I planned to read at the Gross-Out contest at World Horror Con, and that book (as well as some of the other hardcore epics of the day by Edward Lee) awakened me to just how far I would have to go to really stand out. You couldn’t just use splatter horror for a template—you had to go beyond what even movies would show. That was much of the impetus, particularly in trying to create that feeling of shock some of us felt watching a movie like Make Them Die Slowly or Joe D’Amato’s Buried Alive on video back in the day. Something that went far beyond the Freddy and Jason fare that had lapsed into greatly diminishing returns. Since even mainstream horror goes so much farther now, it’s harder to conjure the feeling of witnessing something you weren’t meant to, like those Euro horror atrocities in the video age or the imagery and lyrics of the Chris Barnes era of Cannibal Corpse. Do I see that genital violence as a punishment? That element is sometimes there, but not always. Sometimes it’s just the random cruelty of fate. It’s also a part of you that is usually hidden from the world, so there’s an added element of violation to it, as well as the awareness of how sensitive those areas are.

5. Mutilation Pro Quo. Along lines similar to the last question, some of the violence in your stories seems rooted in payback, particularly payback for men who have sexually objectified or harassed women. Even though in the postscript you say you’re “not big on moralizing,” is cosmic justice ever at work? Do you see yourself indulging a feminist—or at least anti-misogynist—streak? Why or why not? How do you think your own treatments of gender relations compare with gender relations in hardcore horror more generally?

RH: It is a little funny to get a question like that, because after Genital Grinder, many would swear I must be an avowed woman hater. I feel like there was equal opportunity eradication in that collection, but there are prevalent misogynistic attitudes in it for sure, since some of the stories are about killers, and I was influenced by reading a lot of true crime back then. I wasn’t trying to redress a balance in Transcendental Mutilation, so much as just exploring the consciousness of the kind of person who would be amenable to revenge porn (“Threesome”) or online indecent exposure (“Junk”). I see these stories in particular as part of the EC Comics end of the spectrum, where somebody receives an ironic comeuppance, so I suppose that’s a sort of cosmic justice at play. As for my treatments of gender relations, though, like you alluded, I try to avoid moralizing. I don’t want to come off as didactic. I’m trying to present everything as part of a story, not a sermon. I don’t know that it’s necessarily a hardcore horror staple to go the other way with it, but it seems like a broader tendency in books and film in general now, to their detriment. I want my work to stand apart from that.

6. Transcendental (Sub)genres. While most of the tales have what we might fairly call supernatural components, some come closer to more familiar supernatural subgenres, such as tales interested in the modern mythic, (sub)urban and internet lore—“Down There” and “Junk,” perhaps “Threesome”—and stories of the occult/religious—“Angelbait” and “Temple of Amduscias.” Did you set out to write out in these subgenres, or did you follow your muse and end up there? How do you feel about these categories and this sort of categorization?

RH: “Down There” just sort of happened. I owed a story to Matt Shaw’s Masters of Horror anthology, and there was a news item about the girls in Michigan who stabbed another friend as a sacrifice to the Slender Man. I started thinking about how ominous the woods seemed when I was a kid, riding past them on the school bus, and how eerie the woods still seem. I started from that fear and “Down There” just revealed itself to me day after day. That doesn’t often happen for me with short stories. I usually have to know where they’re going in advance, or they don’t go anywhere. With “Angelbait,” I was reading about some of the sickening things saints had purportedly done, and how an angel was said to have appeared at one martyrdom. I thought, “What if that was someone’s goal?” Everything fell into place with that. “Temple” was intended for a King Diamond tribute anthology. Jarod Barbee of Death’s Head Press reiterated to me that he wanted something a lot more reliant on atmosphere, so I needed a place that was quiet and isolated. A lot of King Diamond/Mercyful Fate music has occult themes, too, which was another important element, although what unlocked that story for me finally was just figuring out Olivia, the protagonist.

7. Mutilation for Heavenly Purposes. Speaking of “Angelbait,” it is one of the two Splatterpunk Award winners in this collection, and it’s powerful, reminding me of two of my favorite filmic works of extreme horror, John Carpenter’s Cigarette Burns (from the anthology TV series Masters of Horror) and Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs (one of my favorite films of all time). Be as vague as you need to be to avoid spoilers: is what this story says about the nature of transcendence, however good or bad, a view of transcendence you mean to profess? Why or why not? Do you think that perhaps, over the years, horror has transitioned from asking “Why is there evil in the world?” to asking “Does good even exist?” Why or why not?

RH: I loved Martyrs, too! I think it’s the rare kind of movie able to resurrect that old feeling of shock over what you are seeing, with a lingering aftermath of disturbance. I’m sure I had it in mind writing “Angelbait,” and maybe subconsciously Cigarette Burns, too. I think a good summary of it thematically is a Satyricon lyric: “Damned or saved, how could we ever know?” In the world of this story, being chosen is a curse, and divine intervention comes with its own horror. Likewise, I think transcendence elsewhere in the collection (“Divine Red”) is something positive, however deranged. In “Orificially Compromised,” it’s more ambiguous… how much of Porter’s euphoria is even his own at the end? Transcendental Mutilation to me means the willingness to ascend above the inherent banality of existence, with characters willing to mutilate their lives, themselves, and/or others in pursuit of whatever higher meaning they aspire to. That’s an interesting question about horror and the existence of good. There does seem to be more cynicism now. Even someone like David Lynch who clearly believes in diametrically opposed good and evil can really drag you through the dark. Perhaps there is this decaying belief in everything—government, media, law, religion, etc., and it manifests in more creative expressions of hopelessness and pessimism.

8. Transcendental (Sub)genres II. In this collection’s other Splatterpunk Award winner, “The Seacretor,” I think what I like best is what I see as transformations among genres, unified by horror: first a shipwreck scenario following Robinson Crusoe (which you tag), which segues into sci-fi, which segues into weird tale. Did you know you would be taking such turns when you first drafted, or were you pantsing it? What do you think the different genre elements contribute to the atmosphere, character development, and impact of the story? Why tree-fucking?

RH: A year or two before I wrote “The Seacretor,” I was watching a movie set on an island, and I started thinking about what I would write with that kind of setting. I came up with the final reveal rather quickly. I also had an older idea about someone crash-landing on a strange planet and becoming “fixated” by a tree, and it made sense to transplant that idea into what became “The Seacretor.” A tree just made sense as something that would be in that landscape, and I came up with what I thought was the most unexpected effect it could have on the characters. I remembered the idea when I owed Jack Bantry a story for Splatterpunk Forever. I didn’t have the group dynamic figured out beforehand, but as soon as I started writing it in first person, it all came together. I had a couple of Stephen King stories in mind—“Beachworld” from Night Shift and “Survival Type” from Skeleton Crew. I think there’s something really potent about a scenario where characters are stranded, because you’re immediately thinking about what you would do in that situation. How long could you do the sensible things before desperation drove you to something you wouldn’t have ever considered a few days before? And what if your only options ended up transforming you? There’s a contrast I like in the story about the beauty of the scenery with the loneliness of Ben, the protagonist, who may be losing Tanya to an annoying rival. In stories without a technological backdrop, I like the conflict to be born of something primal or ancient, and who knows how many strange aeons that island has been there?

9. Transcendent Transgression. Barring child pornography, can you imagine a story that would go too far to write? If so, what would it involve? If not, why not?

RH: I have found myself thinking certain scenes might be going too far sometimes. There is one in The Night Stockers where I knew some people were likely to quit reading then and there. There’s one in The Profile, too, where I thought maybe it was too much. But I also felt good about both those scenes, that they turned out well and had the effects I wanted. I even read the latter at KillerCon last year, and people laughed in all the right places. The wanton violations and mutilations of Von and Greg were perhaps viewed differently in 2012 when Genital Grinder was published than they would be now, but I think that’s probably also the appeal for readers just discovering GG… some stories may seem even more hardcore now than what I wrote them in 1999-2002 or so. I feel like a book with Von and Greg in such a different social climate is a bigger challenge now. I have to do it, though, one of these days. What would such a story look like? Our luckless duo will be attending college in this scenario. Anyone familiar with them can see why that would be such a disaster, with all the collateral damage of gender relations and generational and class differences, among others. Something with all the wrongness and hilarity of Edward Lee’s Header 2 that remains true to the respective personalities of our beloved degenerates, such as they are.

10. Access! How can readers learn more about you and your works (please provide any links you want to share)?

RH: I have a Linktree here: https://linktr.ee/necroaf?utm_source=linktree_admin_share..

That covers a lot of ground, but I’ll also go ahead and throw in my Amazon page here: https://www.amazon.com/stores/Ryan-Harding/author/B01N1HSDZ5

And Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ryanhardmorbid

Thank you for this interview and the insightful questions!

About the AuthorRyan Harding is the four-time Splatterpunk Award-winning author of books such as Transcendental Mutilation, Genital Grinder and collaborations with Jason Taverner (the Agent Orange slasher novels Reincarange and Reincursion), Kristopher Triana (The Night Stockers), Lucas Mangum (Pandemonium), and Edward Lee (Header 3). He contributed the novella The Profile to the anthology Call Me Hoop, and his short stories have appeared in anthologies such as Brewtality, The Distended Table, The Big Book of Blasphemy, The New Flesh: A Literary Tribute to David Cronenberg, Splatterpunk Forever, Past Indiscretions, Into Painfreak, and The Year’s Best Hardcore Horror Vol. 3. His work has also been published in German, Italian, and Polish. Upcoming projects include a novel with Bryan Smith and the third book in the Agent Orange series.

The post Interview with Author Ryan Harding: Transcendental Mutilation appeared first on L. Andrew Cooper's Horrific Scribblings.

January 17, 2024

Interview with Author Christine Morgan: Trench Mouth, The Infernal Series, The Night Silver River Run Red, and More

Award-winning, extreme, and diabolically clever horror author Christine Morgan is here to discuss some books you can get your filthy hands on now and a few more coming monstrously soon.

Trench Mouth Click the pic for more!

Click the pic for more!Fathom Five … a state-of-the-art oceanic research facility, suspended far below the surface. There, in the dark and the deep, a team of top-notch scientists studies the ecosystems and denizens of an aquatic environment as alien as another planet.

There, they also conduct illicit experiments upon hapless human subjects, with the goal of giving our species a chance to adapt to a changing world. Or, at the very least, to create mutant freaky fish-people, because, why not?

Oh, the arrogance and hubris of genius! Oh, the freaky things that already dwell in the strange, hostile depths! In the cold, crushing, silent pressure of a blackness lit only by eerie bioluminescence. Things that don’t take kindly to intruders. Things that are ancient, and enormous, and hungry.

Things like … TRENCH MOUTH.

“Think Sea Lab of Dr. Moreau meets Jersey Shore, plus enough gore and body parts to fill entire coal hoppers; add to that, Morgan’s uniquely visual style that rams it all in our faces in glorious Technicolor.”

—Edward Lee, author of White Trash Gothic

“This is exactly the kind of book I love. Supersonic pacing. Blood spilled on every page. A grisly weird-science techno-thriller set in the crushing stygian darkness, Morgan’s Trench Mouth lures you in and leaves you gasping.”

—Lee Murray, three-time Bram Stoker nominee and author of Into the Mist

Lakehouse Infernal

“Lakehouse Infernal is the coolest, ball-bustingest, most outrageous, and most ENTERTAINING horror novel you’re likely to find in a long time.” – Edward Lee, author of City Infernal

Lake Misquamicus was an unremarkable lake in Florida, unremarkable that is until suddenly it was filled with six billion gallons of blood, bile, pus, piss, shit and …things… directly from the pits of Hell. First the public was in shock, then the government built a wall, and as time passed it became another urban legend. But for some, it has become a travel destination. Spring-breakers, drug-runners, and religious nuts. But a weekend getaway on the shores of Hell may not be the safest idea…

With an introduction by and officially endorsed by splatterpunk legend Edward Lee, Lakehouse Infernal is an official entree in Lee’s infamous Infernal series. Christine Morgan (Spermjackers from Hell) expands on this universe with her own twist on hardcore horror tourism.

“Think Spring Break, only instead of a beach house, it’s a lakehouse, but the lakehouse IS IN FUCKIN’ HELL, that’s right, a chunk of Hell that’s been upheaved and pushed up into our pretty little world—sunny Florida, no less!” – Edward Lee

Warlock Infernal

6 6 6

Six minutes into the unholy consummation, someone finally thought to cut the live feed … but the momentous events were only just getting underway! As the Hell-Centurion Favius claims his kingdom and queen, as the Wall rises and the Dome descends, the survivors trapped inside will face some critical decisions.

Six hours ago, Gregory Nachtwald was holding hands with an angel … and how can anybody go back to any sort of normal life after that? Especially as a newly-awakened warlock with a dark and mysterious family legacy, possessing powers he hardly understands?

Six days later, they went for the nuclear option… a disgruntled and betrayed nation, and a terrified world, preparing to unleash their ultimate weapon against the diabolical stronghold that had once been a remote Florida lake.

Welcome back to Lake Misquamicus for another smutty, gory, depravity-laden adventure in Warlock Infernal, sequel to the Splatterpunk Award winning Lakehouse Infernal!

The Night Silver River Run Red