L. Andrew Cooper's Blog

October 16, 2025

Supercosmic Dark Heroes: No One Can Save Us by Kendall Phillips

Adam always keeps his powers in check. As the world’s only superhero, he must know his limits. Defeat the master criminal, repel an army, stop a natural disaster, but never let himself go too far.

Until Syangnom.

The world has grown accustomed to the feats of its only superhuman. Adam’s wife, Sara, a celebrated journalist and periodic hostage, regularly reports his exploits, and the agents of Extra-Judicial Affairs handle all the legal issues.

But when Adam becomes enraged in the reclusive regime of Syangnom, he leaves 14 million people dead and the world recoiling from the destruction he has wrought.

Now Adam’s wife Sara and EJA Agent Pia Mercado must track down the conspiracy behind Adam’s breakdown and discover the otherworldly source of his powers. Their search will bring them face to face with supervillains, eldritch gods, and the mysterious figure who defends Chicago from the shadows, the armored hero known only as No One.

Click the image for more on Amazon!The Review

Click the image for more on Amazon!The ReviewThe fusion of comic book superhero action with Lovecraftian weird and mythos elements to form the backbone of Kendall Phillips’s No One Can Save Us places the book in rare company (think Dr. Strange), inviting readers to share in its deep indulgence of the thoughtful, scary fantastic.

What makes the book’s company even rarer is its addition of unsettling depth and realism in its characters, exemplified in the story’s depiction of the impact of charged-with-superheroic-powers Adam’s activities not just on the world but on his wife, Sara, who had the leading career in the relationship until he got his powers. Adam’s zealousness in protecting Sara, logically, makes Sara a target, a prisoner of his escapades, but with her own heroic streak, she rises to a series of challenges, becoming a protagonist rather than a background character waiting to be rescued. The sharp edge of Adam’s protective instinct and Sara’s response to it are only the beginning of how the story takes apart simple notions about superheroes and heroism. Score one for the title.

Another rare but logical aspect of superheroic existence that the book includes is government response, not just the violent stuff, which is familiar enough, but bureaucratic effort and meltdown, which is scary in a way that should remind us that Kafka and Lovecraft were contemporaries.

A lot of the real fun, though, is the action sequences, which flow in Phillips’s smooth prose like invisible editing of shots that cost millions and millions to produce, explosions and cars flying and OMFG superheroes mean supervillains with super-gadgets and super-weapons, and as the situation escalates, things get more super. The villains deserve special note. They’re as unusually well-rounded as the heroes, and they have wonderful toys, nanobots and giant robots capable of virtual magic. As the story progresses, things get messier, with lines between hero and villain becoming blurrier, which increases the dark fun.

As the story progresses, things also get weirder, and Lovecraft fans will enjoy a trip to Miskatonic University when the Lovecraftian elements start to take center stage. Characters contemplate their smallness compared to both the titanic monstrosities they face and the implications of the powers involved, invoking true cosmic horror. The tentacle count gets very, very high.

While the horrors are considerable, I’d say this novel is still mostly about heroes and heroism, so Phillips’s choice to put Homeric wordplay front and center is apt. The book offers itself as pure enjoyment, but if you’re so inclined, you can think of it as a meditation on heroes—in the tradition of Odysseus—who have enormous power. It considers who really might use such power to do some saving, the implications of the saving (or not saving), who needs to be saved, and who doesn’t. Salvation is, after all, big business. Cosmic business. Score two for the title.

The bottom line: No One Can Save Us is a romp with superheroes, supervillains, and Lovecraftian monsters, at times light-hearted and at times cosmically dark, that combines city-levelling action with well-crafted characters and prose that keeps the pages turning. The richness of its people and plot will reward genre fans and more casual readers alike.

The post Supercosmic Dark Heroes: No One Can Save Us by Kendall Phillips appeared first on L. Andrew Cooper's Horrific Scribblings.

August 22, 2025

COVER REVEAL: Battling Darkness and the Divine during CRAZY TIME (Second Edition)

Once again, I am indebted to the brilliance of cover designer Ruth Anna Evans:

Horrific Scribblings is publishing a second edition of my surreal horror novel Crazy Time. I adore the new cover and am happy to have made the book better in other, subtler ways. The story is not splatterpunk or “extreme” in the subgenre sense, but it is transgressive and very, very dark. People have been offended (yay!) and found it too damned weird (yay!), but otherwise, I haven’t had many complaints. But I haven’t had many readers, either, so I’m hoping this new edition will find Lily Henshaw, the main character and possibly my favorite creation, many new admirers.

Reviewers are at work! More information is coming!

Oh, what’s the book about?

On a dark urban highway, bright, introspective thirtysomething Lily Henshaw survives a brutal attack by men who announce that “It’s Crazy Time!” and kill her friends. Months later, still crushed by survivor’s guilt, Lily suffers another serious trauma—and another, and another, and another. Deaths, especially suicides, surround her, as do strange occurrences that, despite her agnosticism, seem to have Biblical import. She becomes convinced she is cursed like Job from the Bible, but unlike Job, she doesn’t assume God is the good guy. While intense stresses foster an unlikely romance with her boss, she goes on a quest for answers that involves a psychic, a Satanist, a Protestant preacher, and others, gaining resolve and a destination: the skyscraper where she might confront the supernatural forces aligned in a conspiracy to destroy her life.

If you haven’t read it–and chances are, you haven’t–prepare for a dark treat. The new edition drops November 18, 2025 in e-book and paperback. For sale now on Amazon.

The post COVER REVEAL: Battling Darkness and the Divine during CRAZY TIME (Second Edition) appeared first on L. Andrew Cooper's Horrific Scribblings.

July 30, 2025

COVER REVEAL: Psychology Gets Under the Skin in THE SKINNER EFFECT

After university authorities observe a gruesome experiment that psychologist Dr. Stanley Burrows performs on rats, an experiment during which one of his graduate student assistants is injured, Dr. Burrows and his only loyal assistant, Edward Pine, accept exile from the academic world and embrace new supporters who want them to do different sorts of experiments on human subjects. Dr. Burrows has limitless resources to develop innovative processes for behavioral conditioning that achieve extreme outcomes. He programs his subjects with violence so they will commit violence. Spurred by conclusions drawn from the thinking of radical behaviorist B.F. Skinner, he will use his subjects to demonstrate not only the bloody extremes for which he can program a “human” but also a new understanding of “the human” susceptible to programming.

Click the image to order The Skinner Effect (~27,000 words, or 84 pages) on Amazon

Click the image to order The Skinner Effect (~27,000 words, or 84 pages) on AmazonCOVER ART BY THE MAGNIFICENT RUTH ANNA EVANS

“The Skinner Effect by L. Andrew Cooper is not for the faint of heart… a complex psychological experiment wrapped in an extreme horror disguise… fans of extreme horror will love this book.” –JG Faherty, author of Hellrider and The Malthusian Correction

“Somehow, the author manages to mix psychological horror with a gorefest and a bit of conspiracy theory on the side with excellent results in this book. Truly terrifying. This story will haunt my nightmares for a long time.” –Maria, ARC reviewer

“I can’t say I will now be frequenting the splatterpunk genre, but I know I will be reading more from L. Andrew Cooper. It’s dark, it’s messed up… I put my stomach aside and read it all. Ravenously. I know I will be reading this again in the future.

My only complaint is as the book progresses the horrors become so outlandish that I ceased to be fazed…

Or… maybe now I’m numb.

Perhaps…

Perhaps I’ve been conditioned.” –Jonny, ARC reviewer

The post COVER REVEAL: Psychology Gets Under the Skin in THE SKINNER EFFECT appeared first on L. Andrew Cooper's Horrific Scribblings.

July 2, 2025

Interview with Author Joseph Murnane: It Eats Your Hunger and Dead Rabbit

The talented Joseph Murnane shares some of his elegant prose in reflections on his novel It Eats Your Hunger and his novella Dead Rabbit. exploring how dangerous appetites become terrifying tales.

It Eats Your Hunger“It Eats Your Hunger is the kind of horror that takes up residence in your soul. It’s Hunter S. Thompson, it’s Kerouac, and it’s Straub. It’s shocking that this is Joseph’s debut novel. Many of the most seasoned writers couldn’t pull off the level of raw grit and honest, saw-tooth prose this book punches with.”

—Gage Greenwood, Author of On A Clear Day, You Can See Block Island

Ren has a problem, and it’s not his heroin addiction.

Or that he’s wanted for murdering his stepfather.

He’s being haunted by something far worse than the ghost of his dead sister.

When he hitches a ride with Lefty, Jersey, and Geena, a group of itinerant addicts on the run from their own problems, he starts to believe maybe things are looking up.

But there’s something wrong with Lefty. Something unnatural.

Something that wants to see them all dead.

Can Ren stop it in time, or will he end up torn apart on the side of the highway?

Or worse?

Click the image for more on Amazon!

Dead Rabbit

Click the image for more on Amazon!

Dead Rabbit

From the award-nominated author of It Eats Your Hunger comes the story of Adam Bell, a young man who accepts a job at Wild Mountain Wolf Sanctuary, a hidden facility in a secluded corner of the New Mexico desert. The work is hard but fulfilling, helping Adam come into his own and take hold of his humanity. However, beneath the earth, The Rabbit Man is awakening, a wretched terror hellbent on stripping that humanity away. Plagued by horrific visions and running out of time, he has a choice: fight to survive or become nothing more than a forgotten Dead Rabbit.

The Interview

The Interview1, Horror Class-ification. Before I read Gage Greenwood’s blurb (above), I’d already thought of your novel It Eats Your Hunger as blending aspects of Kerouac and Thompson with the supernatural horror genre (I didn’t think of Straub in particular). Are these authors influences, and if so, how? If not, why do you think people like me see connections? Your novel as well as your novella Dead Rabbit engage significantly with aspects of road narrative and American regionalism common to both Beat and Gonzo writing but also often—like a focus on disaffected, introspective youth coming of age, which you also have—qualify works as “literary.” Do you think of your work as literary? Why or why not? What’s at stake in calling a work “literary horror?”

JM: Thompson is probably the biggest influence in the bunch for me, but it wasn’t intentional. When I got that blurb back from Gage, it honestly made me quite weepy. It really meant a lot to me. Thompson is probably my favorite writer and was the reason I majored in journalism in college—at least until general life pulled me away from academia. I’ve always been attracted to the way he can swing from the most outlandish, probably-not-true-but-who-knows beats, over to deep, hard hitting truths that are as undeniable now as they were when they were written. Seriously, go back and read some of the essays in The Great Shark Hunt, maybe swap out the name of a politician or two, and it’ll be hard to tell they weren’t written for the era we live in.

Not too long ago, I did my first speaking event where I read a few pages of Hunger and chose a topic to talk about in a mini-lecture. I decided to talk about “the truth in the lie,” as I like to call it, which for me is the heart of what I’m always shooting for. Especially with Hunger, it exists because I needed it to. It really helped me to process some things I still hadn’t quite allowed myself to feel, even years after the truths my lies are based on. I don’t just want to write scary stories, though of course that’s always at the forefront of my mind—this IS horror, after all— but I want to write stories that really mean something to people. I never saw a point in trying to write something until I felt like I really had something important to say. Does that make me literary? I honestly don’t know. I like to think it does, but in the end, I’ll leave that definition up to the people that encounter my body of work. For me, I’m just trying to say the things I need to in an entertaining and meaningful way.

2. Hunger I: The Feeding Experience. Another commonality It Eats Your Hunger shares with works by Beat and Gonzo writers is that it reports, in a fictionalized manner but with accuracy your afterword links to experience (and that I can partially confirm with my own experience), first-hand perceptions influenced by various drugs. To what extent do you set out to create fiction about altered states of consciousness? How might representing characters in altered states enhance your options for characterization? You represent various drugs that lead to diverse experiences: cocaine, LSD, a variety of opiates. Are you cataloguing different drugs’ highs and lows as characters take them to feed their appetites? Why or why not?

JM: Well, it’s not something I intend to make too much of my work about. I’d hate to pigeonhole myself, but addiction will come up as a theme from time to time. It’s been too much a part of my life not to. In Hunger, it’s not so much a cataloguing as a tool of characterization. They all have different “poisons.” so to speak, and in turn, I consider each of the different central characters little pieces of myself. Stuff like dream sequences, psychedelic trips, and the like all served to enhance this feverish, disoriented state that I spent so long living in. That being said, I feel like I got most of what I needed to out on the subject, and I’m looking forward to other ideas I’d like to explore. Take for example our protagonist in Dead Rabbit. As it’s also semi-autobiographical, we do get a mention of addiction at the top as part of the inciting incident that puts Adam in the setting of the story, but I was very intentional in not revisiting those feelings throughout the story, because while it played a role, it’s not what that story was about.

3. Hunger II: Inviting Monstrosity. The title It Eats Your Hunger suggests something undesirable feeds on the desire to feed…. Your book doesn’t focus on appetites for food or non-alcoholic beverages; it focuses on intoxicating and self-destructive appetites. What’s different about these appetites, and why do they invite an it that wants to feed on them? What’s so delicious about them? Are they evil appetites? Does your book make any moral judgments about such appetites in general or at all? How do you think an it that eats such appetites qualifies in the moral realm?

JM: To put it simply, these appetites stem from a need for comfort. They thrive on fear, pain, and sadness, providing a sort of mental kill switch that allows us to turn away from those feelings. The “It” that they invite comes in all sorts of forms, but they mostly take the shape of consequences. They’re delicious because they let you look away, but they’re insidious because all those things are still there, just out of frame, waiting for you when you wake up, only now they’re a little bigger, a little harder to carry.

Are they evil appetites? I actually fully reject that they could be. Selfish, maybe, but evil? Is it evil to be in pain and seek relief? I think not. Especially as somebody who’s been there, it was important to me NOT to moralize over the actions they took. Lefty is an asshole. He’s manipulative, mean, aggressive, and all kinds of bad. He also deeply loves his brother, even if he rarely shows it. And just like anybody else, he’s in great pain. Sure, he commits some evil acts under the spell of his addiction and trauma but no, I wouldn’t call him evil. He plays his hand, and it brings him where he’s going, but in the end, he’s just hurting like so many of us, and I have great love for him.

4. They Do Not Mean To, But They Do. In the cluster of young people at the center of It Eats Your Hunger, traumatic pasts are the norm. In their historical moment and/or the present, do you think they represent the condition of youth? If so, what has given rise to that condition? If not, why put this exceptional group in the center? At least as many parents and stepparents in your novel seem to be abusive as not—why these extraordinary circumstances, or, to borrow from Stephen King’s Christine, do you think “part of being a parent is trying to kill your kids?”

JM: Hunger isn’t really trying to make a statement about society, the youth, or anything on such a wide scale. This story is about me, and to a lesser extent, some of the people I came up with. However, it’s become a lot more acceptable to talk about and acknowledge these traumas in the public sphere, so it can seem like there’s more of that, but I don’t think that’s the case. I think we just talk about it now, and that’s great. That’s how we heal. As for how it pertains to the characters in Hunger, I’ve known a lot of road-bound punks in my day, and so many of us have similar stories. I think that’s part of what put us on the road to begin with. Whatever mistakes get made along the way, we step out onto the highway, not looking for trouble, but for freedom. It doesn’t matter if we’re running away from or toward something—some of us just need to run.

If it does speak to anything in wider youth culture, I like to think it’s speaking to a mentality that’s dying out. Kids now are encouraged to feel their feelings a lot more than I was in the 90s, and even more than generations before me. There’s still a lot of work to do, but in my opinion, the kids are going to be okay.

5. Being a Monster. Your characters in It Eats Your Hunger have more in common than trauma. Theft and other smaller crimes don’t seem to faze them, and more than one of them commits murder while others aid and abet. Do you expect readers to find your characters sympathetic and/or relatable? Do their traumatic pasts and/or material circumstances and/or other factors mitigate their more questionable acts? What’s scarier or more monstrous about this novel—the supernatural elements or the characters’ downward spirals and escalating depravity?

JM: This sort of goes back to what I was saying earlier about refusing to moralize over the decisions they made. These are people forever living in fight-or-flight mode. Whatever pain they inflict isn’t born out of a desire to cause harm, but of the tools they have at their disposal to survive. We all like to think we’d be above certain actions, even in the worst of scenarios, but how can we know? Do I expect readers to empathize with them? I don’t know, but I certainly hope so. If I did my job, I painted a picture of people at their most human, which is to say their most flawed. Understanding will always have more value to me than judgment, and as somebody that’s done things I would have told you never could have happened until they did, I really believe most people are just a month of bad luck away from making some pretty questionable choices themselves. As for the last question, the human side is always going to be scarier to me than the monstrous, because that’s us. That’s what we have to contend with. I don’t believe in any demons other than the ones we build ourselves.

6. The Big Good Wolf. Your afterword for your novella Dead Rabbit also links it to personal experience, working with a wolf refuge, and your admiration for the animals shows in both It Eats Your Hunger and Dead Rabbit. In the horror genre, wolves usually get a bad rap, serving Dracula-types or being of the undesirable were- variety. To what extent is Dead Rabbit a redemption of the wolf for the horror genre, an entry that shows them as beautiful creatures in harmony with nature? What’s so majestic about wolves, anyway (this is your invitation to gush, please)? While wolves are in harmony with nature, they’re also connected with the cosmic… why?

JM: Yeah you actually really nailed it here. People have such misconceptions about wolves, especially in media. They’re so often depicted as monstrous, ravenous enemies, and I’ve always hated that. When Adam arrives at the sanctuary and meets a wolf for the first time, he looks into its eyes and falls into tears, thinking of everything that brought him to that moment. That’s pretty much exactly how it happened for me. That first encounter was one of the closest things I’ve ever had to a religious experience. It’s so hard to describe, but I encourage you to meet them for yourself. There’s a lot that people don’t understand about them, from their absolutely vital role in their ecosystems, to their family dynamics, to how differently they’re wired from dogs. Take for example the “lone wolf” stereotype. Whenever I hear somebody describe themself as a “lone wolf,” I can’t help but smirk because there is only one thing a lone wolf is doing, and that’s searching for a family. To be a lone wolf as a point of pride is to deny yourself one of the most important things that make us what we are.

As for the connection to the cosmic, we only need to go back to the moment we’re looking into those eyes. You can feel the depth there. Wolves have such deep insight and intuitiveness that’s so hard to quantify. That old cliche, the one about looking straight into your soul, isn’t something I could ever feel in such a concrete way until I looked into those eyes and felt seen in a way I never had through the eyes of an animal. As a matter of fact, I never really believed in the concept of a “soul” until my relationship with wolves showed it to me.

I lived at Wild Spirit for a year, and during that time, we lost plenty of animals to old age, illness, etc. When a wolf passes away, something interesting happens. The others mourn in such a clear, direct way. Their playfulness drops, their body language changes, and while usually any howl is cause for the whole facility to break into chorus, when a wolf is in mourning, they often howl alone, with the others just…holding space? It’s a different sound, one you feel in your bones. It’s not a wild, raucous song like the typical sounds we’d expect to hear. It’s the mother, weeping over her child’s casket as it’s lowered into the earth, and it’s impossible to hear without being profoundly affected.

7. The Gothic Manuscript. Dead Rabbit uses a trope as old as Gothic/horror itself, the “found manuscript” that becomes part of the manuscript and eventually allows the past to become an integral part of unraveling the mystery of the present. Why did you decide to include the diary as part of your story? Why include images of the handwriting? To what extent did you think of the tradition of manuscripts in Gothic/horror (recall that Frankenstein and Dracula are both made of letters and diaries)? Do you want Dead Rabbit to appear to be more in line with tradition, or would you prefer people to see it as an unconventional departure from horror’s touchstones?

JM: I initially decided to use the journal entries as a purely structural/mechanical choice. My goal for the story was always a 30k novella, and I knew we were going to spend a significant portion of that just travelling and world building. The journal entries were a way to sort of say “the horror bit’s coming. Bear with me!” I wanted to spend all the time I needed on pure character, while also making sure it’s clear from the outset that this is still a horror story. Also, yes, I did intend for this story to be more in line with traditional horror writing. I love epistolary stuff, and after the experimental fever dream of Hunger, it was quite refreshing to tell a more traditional creepy mystery. And showing the actual handwritten journal entries? That was all my wonderful editor Jyl Glenn’s idea. She even hand wrote them herself and formatted them into the final product. At the time, I didn’t intend on this one having an audiobook, so that extra flair was sort of a way to bring a little theatricality to the text. And if I can plug Jyl for a second, I highly recommend checking out her website for anybody in need of an editor who’s going to put their all into enhancing your voice.

8. Hunger III: Meat. Dead Rabbit and It Eats Your Hunger both deal with supernatural hunger. How do the hungers in the two works compare? A wolfish hunger seems like something to fear, but ultimately The Rabbit Man becomes the ultimate source of fear in the novella. Why? I ask this question even having seen David Lynch’s Rabbits: what makes rabbits scary? Your Rabbit Man, like your wolves, has a cosmic dimension. Why would a cosmic entity have a rabbit form? What about a rabbit—physically, psychologically, sexually—makes it significant to humanity and beyond?

A different sort of rabbit man from David Lynch

A different sort of rabbit man from David LynchJM: The Rabbit Man all comes down to my real-life experience, namely the scene where RB and Adam go hunting. That’s exactly how it happened in real life, and I’ve always carried that. The original concept was completely born out of killing a rabbit wastefully, and what revenge from a supernatural entity might look like. I’m a bit of a pantser though, so as I went, it all grew into something else on its own. The hunger aspect here is sort of a nod to the phenomena of rabbit starvation (which was almost the title!). It’s incredibly lean meat and can’t keep a person going on its own. If all you eat is rabbit, it just isn’t sustainable long-term. It’s really fascinating to look into so I encourage digging that up! The significance of the rabbit to humanity and beyond isn’t something I put much thought into. I can only truly honestly speak from my own perspective, and I tried to keep a narrow focus on that, but if I had to draw one line between them and us, it would be that universal need for companionship, love, safety, and the consequences when that need is denied.

As for comparison, the hunger in IEYH is more about a craving for relief from existential horror, while the hunger in DR is about physical need as a symptom of greater problems, so I sort of look at them as two sides of a coin.

9. Audiobooks. You were kind enough to share audiobooks of It Eats Your Hunger and Dead Rabbit with me. I think I’m weird in that I look at the words as an audiobook reads to me, but doing so increases the enjoyment immeasurably. How do you imagine people generally using your audiobooks, and what do you think is the importance of audiobooks, especially for indie/rising horror authors, in general? Your audiobooks feature Tom Jordan, whose articulation is as crisp as his tones are mellow and soothing (except during moments of character distress, of course). What do you think makes him a good match for these two stories? Do you see yourself doing audiobooks in the future? Why or why not?

JM: By day, I’m a chef. I work alone, and I listen to audiobooks almost every day. It’s how I keep myself in words when I struggle to pick up a book to physically read. I struggle with depression and anxiety, and sometimes I just can’t connect with physical reading because my thoughts are too scattered. I think audiobooks are so important to accessibility, and without them, I wouldn’t be the reader or writer I am today. Tom specifically just lines up perfectly with my audio goals. I was maybe 10k words into Hunger the first time I heard his work on Andrew Van Wey’s Head Like A Hole, and I just fell in love with it. I wrote the rest of Hunger with him in mind. He really elevates the material in such a way that when I’m listening through and proofing his work, I can’t even believe that I wrote it! Whenever possible, I will always have audio available, and while I have other narrators I plan to work with for specific stories, Michael Crouch and Joe Hempel both high on my list, Tom’s always going to be my default for as long as he’ll have me. Like I said before, I originally didn’t plan on doing an audio for DR due to budget constraints, but Tom read it and actually came to me with an opening in his schedule, asking me if he could produce it at a royalty share rate, so we were able to make a deal.

10. Access! How can readers learn more about you and your works (please provide any links you want to share)?

JM: I distribute through KDP, so my work can be found on Amazon primarily, and is included in KU! I also sell signed copies from my personal shop:

Also, I’m featured in several anthologies. One unannounced that I can’t mention here yet, but Crumpled, organized by Jyl Glenn, as well as another called Phobophobia by Jyl Glenn and Savannah Fischer, which is an exploration of unique fears. That one was released on June 30th.

Also keep an eye out, because Jyl and I are partnered up on an Iron Maiden tribute anthology, which we’ve just finalized the TOC on, that will be releasing around October.

On socials, I’m active on Facebook for my main profile and an author profile: Joseph Murnane-Author

IG: 2_Buck_Yuck and joeykoyote4752

TikTok: Joseph.murnane

About the Author

Joseph Murnane lurks at the mouth of a cave off the banks of the Eno River in Durham, North Carolina, with four hellish animal companions and an eldritch queen of terrifying beauty. They say you can see him there just before dawn, but only out of the corner of your eye, and only if he wants to be seen.

The post Interview with Author Joseph Murnane: It Eats Your Hunger and Dead Rabbit appeared first on L. Andrew Cooper's Horrific Scribblings.

June 4, 2025

Interview with Author Ed Downes: Frozen Echoes

Novelist Ed Downes discusses filling his new creation, Frozen Echoes, with horrors of Antarctica touched by several of horror history’s greatest and reflects on what makes the alien really alien–and what might happen if we came across aliens for real.

Frozen EchoesDr. Flint Hill, an Antarctic researcher, has a centuries-old frozen ship burst through the ice near his base.

Dr. Eva Ward, a cultural anthropologist, journeys deep into the Amazon jungle to investigate a strange flute recovered at a dig site.

Hill is overwhelmed when a mysterious duo shows up in a helicopter, followed by the United States Navy, both drawn by a strange signal emitting from the frozen ship.

Back in Sao Paulo, Eva fights off an attacker set on stealing the flute and ending her life, fleeing to a hacker friend to hide.

Aboard the ship, Hill and the Navy discover the remains of a strange creature before the ice closes around them, threatening to end their investigation prematurely.

Eva’s friend takes her prisoner, forcing her to escape and make her way toward the one clue he provided: Antarctica.

Joining forces, Flint and Eva use the Navy’s resources to head under the ice, where they find the frozen echoes of a civilization waiting to be reborn. But is the cost one they’re willing to pay?

Click the pic for more on Amazon!The Interview

Click the pic for more on Amazon!The Interview1. “Anything weird with the penguins?”: Antarctic Echoes. What inspired you to write a story primarily set in Antarctica? What moods, themes, and images do you like best when surrounding your characters with so much cold, ice, and inhospitable water? While the Antarctic remains a great unknown for most people and relatively unexplored in both reality and fiction, it does appear in two pillars of the horror tradition: Edgar Allan Poe’s underread novel The Narrative of Arthur Pym of Nantucket (1838) and what is probably H.P. Lovecraft’s most influential novel, At the Mountains of Madness (1936). Lovecraft’s work certainly echoes Poe’s. To what extent, if at all, does Frozen Echoes echo either or both of these works? For Lovecraft—and I’d say for Poe as well—there’s something cosmic and horrifying about the sublimity of Antarctica. Do you find Antarctica cosmic and horrifying? Why or why not?

ED: I have always been fascinated by stories that take place in isolation. And I can’t think of any more isolated place on the planet than Antarctica. I grew up watching movies and reading books that depict horrific scenarios set deep in the Arctic ice shelf. Specific examples that come to mind include John Carpenter’s The Thing, which was one of my favorite movies growing up. Another story that sends chills up my spine was an accurate account of an exploration expedition of Sir Ernest Shackleton when he led the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition in 1914. This expedition’s purpose was to embark on a trek across the Antarctic continent. Inevitably, Shackleton’s ship became ice-locked in the Arctic for a long period of time. And the third example that comes to mind is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, where the climax takes place in the Arctic, where Victor Frankenstein confronts his creature.

I have always enjoyed reading the works of H. P. Lovecraft and Edgar Allan Poe. I won’t get into either of their personal lives or belief systems. I will just comment on their writing capabilities. Both were very talented in creating stories that instill fear. From the suspenseful horror of Edgar Allan Poe to the immense cosmic horror of H. P. Lovecraft, I have always found myself immersed in their stories. There’s no doubt that both of these prolific authors had an influence on the stories that I want to tell. I’ve always loved the way H. P. Lovecraft can make us feel so small and isolated in his storytelling. His ability to weave a story of dread is still unmatched in my opinion. Also, I have always found Edgar Allan Poe to have a unique talent of building suspense that draws the reader in and makes the story unputdownable.

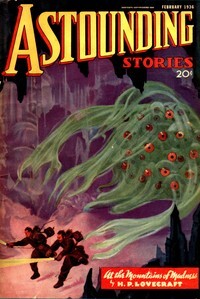

Lovecraft’s classic Antarctic horror

Lovecraft’s classic Antarctic horrorPutting aside for a moment the concept of horror fiction, the mere idea of going to Antarctica gives me anxiety. What I mean is that Antarctica is so far away from civilization and so difficult to travel to and from that going there puts anyone in a highly isolated and vulnerable position. Not to mention, the inhospitable conditions and lack of resources make Antarctica a very high-risk place to visit. That alone to me makes Antarctica a very cosmic place that lends itself to being the fuel of nightmares.

2. Alien Attraction, Alien Horror. A mysterious signal, which your Antarctic scientists think might be a distress signal or could be a warning (like the signal at the beginning of the movie Alien, 1979, another possible influence for you), lures your characters toward discoveries. This initial signal seems to reflect a quality of the idea of the “alien” throughout the book: it is simultaneously too attractive to resist and too horrific to approach. Why the attraction? Why the horror? Why the duality? Without giving too much away, how would you compare your “civilization waiting to be reborn” to other “alien” discoveries? What’s fascinating and terrifying about it?

ED: It’s funny that you bring up the movie Alien. When Alien first hit the movie theaters back in 1979, I was only nine years old. At that time, my parents did not approve of me seeing an R-rated film. So, I could not see Alien for a few years after it came out, and it wasn’t for the lack of trying. I managed to find a book called The Making of Alien, which was a behind-the-scenes coffee table-style book. I drew inspiration from some of the early sketches by HR Giger, whose works of art sparked my imagination to go where it had never gone before. The gothic and ominous nature of his artwork was like nothing I had ever seen. To this day, I find his drawings to be among the most interesting sketches depicting alien life forms and worlds.

Well, eventually I got to see Alien, and it did not disappoint. The pictures in my coffee table book did not do the movie justice. Yes, I had seen the image of the alien bursting through the chest of Kane, played by John Hurt, but seeing it on the big screen in full motion color was a fantastic experience. I still remember the tagline, “In space, no one can hear you scream.”

Alien, no doubt, has influenced my storytelling. And there’s something irresistible about a signal coming from a mysterious place. Especially a signal coming from a place where no signal should come from, a place that almost seems impossible. Really, who could resist trying to find out where that signal originated and who sent the signal?

When looking at comparing of my alien civilization born against other alien civilizations depicted in movies, especially the one in Alien, I am reminded that the unfortunate truth is that if and when we do encounter an alien race sometime in the future, it might not go well.

3. Dual Narrative. As the description (above) indicates, your book has two major protagonists, Flint and Eva, and much of the novel has them in separate places and follows them on separate narrative lines, switching back and forth between their experiences and perspectives. Why did you choose this (mostly) dual structure for telling your story? How do you think keeping your main characters apart—and then in key moments bringing them together—shapes the reading experience for your audience? How did it affect the writing experience? Do you expect readers to enjoy both narrative lines equally? Relate to both characters equally? What’s the thinking behind your expectations?

ED: When I was contemplating this story, I struggled with how to create fascinating characters. In doing so, I realized that the two main characters are vastly different from one another. They both contrast with and complement each other at the same time. It made sense to put them in various settings at the beginning to help build them as characters. First, you have Flint, who is older and set in his ways, lives by a code, and has a pretty solid moral compass. Then you contrast that with Eva, who is younger, ambitious, and damaged, but is looking to discover herself and rebuild her life.

Many of the stories I have read and truly enjoyed follow a similar model, where one or more characters embark on their journey in different places or settings and then come together later in the story. I love the storytelling of Clive Cussler, Preston & Child, or James Rollins, as they have a knack for building these types of stories in a fun and engaging way. However, they are in the traditional action-adventure genre. I still thought it might make sense to follow this formula in the sci-fi horror genre.

I hope the readers will enjoy discovering each of these main characters and see the contrast not only in the characters but in the geographies and climates from which they originated at the beginning of the story. The alternating between the two characters in their respective settings at the start of the book creates a pleasant rhythm, shifting from hot to cold. I am interested in seeing how readers embrace each of the characters and learn which ones they like better or dislike, and why. That’ll be a big fun part for me to experience and learn about building interesting characters for future stories.

4. Narrative Authenticity. I see “scuba diving” in your bio (below), but I don’t see anything about diving in the Antarctic… how much research did you do to capture the experiences of living, working, and exploring in Antarctica, both on the surface and in the surrounding waters? Your characters are scientists, an anthropologist, and military personnel: what sort of research did you do when crafting their personalities, determining the sorts of things they would know, and figuring out how they would talk? In short, what did you do to make your characters, settings, and situations feel authentic?

ED: I started scuba diving back in the early 90s and have loved it ever since. My first exposure to scuba diving was in college as a physical education class. Taking this class qualified me for PADI Open Water certification. A few years later, I continued my certification path with PADI Advanced Open Water, Adventure Diver, and Rescue Diver certifications.

Although I’ve never had the opportunity or desire to dive in cold water, such as the icy waters near Antarctica, I could learn about this type of diving. The cold-water technical diving depicted in my story combines elements from cold-water dives and technical dives. Each has special equipment and skill set requirements. For example, cold-water dives require special heated dry suits, and technical dives require specialized equipment and tools for underwater engineering and labor activities. In such equipment, helmets are worn not only to protect the divers from the harsh elements but also to facilitate radio communication between divers. As part of my research, I had to become more familiar with this type of equipment and its applications.

5. Antisocial Academics. Flint, Eva, and other characters have strong ties to the academic world, but to me at least, those ties don’t seem connected to characters’ more admirable traits. Flint is a consummate loner, annoyed by graduate students… Eva once used her academic access for criminal activity… a villain is an academic known for sexually exploiting students… why does ugliness seem to surround academia in your novel? Is the book consciously critical of academia as an “institution?” What about the military, which also seems to be involved in questionable decisions and activities? If—and feel free to tell me I’m off track—the academics and military personnel are tainted by their institutional identities, is there anybody left to model “good?” If so, who and how? If not, why not?

ED: In the context of this novel, the portrayal of academia and the military has a negative tone, aligning with the story’s narrative and supporting the plot. Flint is an old, crotchety researcher living out his last days in isolation, hiding from the world. He has little patience for tolerating nonsense. At the same time, he enjoys working with students and seeing them discover and fall in love with Antarctica.

Eva, on the other hand, is a different type of character. She’s no longer involved with academia, but she still conducts her consulting work in examining antiquities. She has compromised principles and a moral compass that is off-kilter. This is part of her character arc, which changes throughout the story. A big part of Eva’s outlook on life and compromised ethics stems from the negative experience that she had with a former professor who took advantage of her in a personal relationship and then took credit for her work, all while tarnishing her reputation in academia.

As far as the Navy goes, they are just doing their job in following the mysterious signal coming from under the ice. That irresistible signal that we talked about earlier is so enticing that it can’t be ignored. That and the Navy’s need for security and secrecy as they explore and discover the national security implications of the signal source.

6. “A little lady named Pandora.”: The Ethics of Exploration. On a related note, from the moment the scientists decide to investigate the signal that could lead to something dangerous for them and perhaps for humanity, the impulse to explore and solve mysteries comes into question. Like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), a book that begins and ends with polar exploration, does your novel question the ethics of exploration? Does Flint’s ambition to garner achievements like Shackleton stem from a character flaw? Why or why not? Knowing that gaining access to the echoes of the civilization beneath the ice might be like opening Pandora’s box, do your characters have a moral and/or ethical duty to step away? Why or why not?

ED: It’s like most scientists to be curious about discoveries. In many cases, this desire to discover can be reckless and dangerous. From the beginning of the story, various elements reveal this curiosity. We see students arriving to learn and do research. We see Flint working in the weather station, and we get a glimpse into Flint’s personality and character. Then, with the helicopter crash. And the curiosity surrounding the signal emanating from a mile below the ice.

It truly is a Pandora’s box. And a slippery slope as the scientists and the Navy don’t see what’s coming, and they slowly slip closer and closer into the danger zone as they become more aware of what is going on. I don’t want to reveal any plot details that would spoil the story for the reader.

Interestingly, you ask about Flint’s motivations compared to Shackleton’s. I see your point that some of his actions could be driven from a place of scientific ambition and therefore recklessness. I view Flint as a highly ethical scientist who consistently strives to do the right thing. This can be challenging to balance against the ambitions of scientific discovery. I think in an ideal world, the scientists and the Navy would have a moral and ethical obligation to step away from the dangers to humanity as soon as they realize them. I also believe that a combination of human curiosity and scientific ambition makes it almost impossible for the characters in this story. They cannot avoid Pandora’s box, no matter the cost.

7. Alienness. Although I don’t want to give away too much, your characters do find something “alien,” and your book provides detailed descriptions of alien places and things. Start with the flute: why did you decide to make sound integral to the alien technology? What, in your imagination, helps make technology seem alien? Similarly, you deal with forms of connectedness and communication that are alien to human experience, based more on a “hive” model. Why turn to the “hive” for a sense of alien interconnectedness? You describe alien architecture. What shapes and structures strike you as alien, and why? Eventually, your story calls for narration from the perspective of someone having an alien experience, i.e. going through something humans couldn’t normally feel or perceive. How did you manage that?

ED: Yes! Let’s not give away too much lol. But to answer your question, I’ve always had a fascination with exploring alien worlds and what that might look like. I’ve also contemplated various questions about what alien technology might look like or feel like for humans at length. It’s all an exercise in imagination, but in the world that I painted here in this story, I see the alien species as seeking a parasitic existence with humankind.

One of the plot elements that I was looking to engineer for my story was some sort of artifact that would be the catalyst for Eva to become part of the story. This artifact also had to hold significant meaning in the latter part of the story. All the while, it contributes to the ticking clock through its exposure to the surrounding people. And I’ve always wondered what a flute might sound like if it’s played underwater, and what could that mean, or what could that do? So that’s what I built into the story.

The technology depicted in this story had organic and biomechanical foundations. Materials, tools, and equipment are bio-engineered organically rather than manufactured. It almost had a similar look and feel to H.R. Giger’s concepts from Alien. This type of technology is so foreign to humans that it lends itself to creating more tension in the story and emphasizing the contrast between the human world and the alien world. I think this also can make the reader a little uncomfortable, which contributes to the reading experience.

In thinking about the species of beings encountered by the researchers, I wanted them to be a kind of like the Borg from Star Trek, but my version of that hive mind. I’ve always been a little freaked out by body horror in mutation, so it seemed like a natural direction for me to go in. Because if I’m a little freaked out writing it, I’m sure people are going to be a little freaked out reading it.

As the story progresses, we hear the viewpoint of a human going through a transformation and becoming part of this new species. It brings to mind elements from the movie The Fly. Humans can comprehend and articulate what is going on inside of them. I think this makes the story more relatable and personal for the reader, creating more tension and fear of loss as it progresses.

8. Unpredictable Bodies. Early in the novel, characters learn that exposure to the alien artifacts and structures affects human bodies, leading to death for some and odd changes for others. The term “body horror” has been popular lately: did you write the changing bodies in Frozen Echoes with “body horror” in mind? What do you think of “body horror?” Another work of Antarctic alien horror that might be an influence, John Carpenter’s film The Thing (1982), predates the term’s popularity but qualifies as a masterwork of body horror—to what extent might it have influenced you? Why do you think “body horror” is enjoying a spike of interest for horror’s readers and viewers today? Not all of the physical changes your characters experience are necessarily bad… is an unpredictable, alien, physical transformation ever not horror? Why or why not?

ED: The alien artifact, specifically the flute, was an integral part of the story—almost a nonplayer character, so to speak. I touched on it in a previous question, but let’s go deeper into what’s going on behind the scenes with the flute. Exposure to the energy emanating from the flute has adverse effects on the human body, killing some people and altering others. This is coming from a place of body horror. It’s also a contribution to the ticking clock and helps to establish the stakes at the beginning of the story.

It’s funny that we come back to John Carpenter’s The Thing. Undoubtedly one of my favorite movies of all time and highly influential in my writing. A combination of the isolated setting and the body mutations that take place through exposure to the alien being.

In recent years, we’ve seen an uptick in body horror, I think, and I’m not sure where it’s stemming from, but people seem to love it. Body horror, as I mentioned earlier, has always freaked me out. I think the reason it’s so bothersome to me is that there are changes that the human body undergoes in some situations that there’s no coming back from. One movie I saw recently was called Tusk. That movie gave me nightmares, and I just kept saying to myself, “Well, there’s no coming back from that!”

As you mentioned, not all the physical changes that the characters undergo in this story are bad; a prime example of that is Flint. At the beginning of the story, we see his struggle with his arthritis and his raw hands and the difficulties they create for him in just functioning daily. This is contrasted by the version of Flint at the end of the story, where he has completely changed, and those shortcomings are no longer present, although they are replaced by changes that might not be seen as positive. But I’ll leave that for the reader to decide.

9. Proof? I’m not saying what characters do or don’t discover—and I’m not saying whether your characters or even the planet survives—but I will say that questions arise about what might happen if scientists discovered proof positive of intelligent (even superior) alien life. What do you think: if a team like the one in your novel managed to reveal proof of an intelligent alien species, how would the world react? How would the world change? How much and what kind(s) of proof would scientists need to be generally believed? Would people tend to assume that such a species poses a threat? Why or why not? Do you think the existence of such a species would likely be a threat? Why or why not?

ED: I touched on this briefly in the earlier part of the interview, but I’m glad you brought it up again. There is intelligent life in the universe that humankind will come into contact with in the future. The universe is a big place, and it’s just a matter of time. It sparks the question of what that would look like. And why haven’t we experienced an interaction so far?

An interaction with an alien species could go in many directions. Humans, by nature, are predisposed to fear what they don’t understand and, therefore, would most likely default to a defensive or offensive posture. This could easily lead to violence and either the killing of the alien species or the eradication of humanity.

When asked why we haven’t experienced an interaction with another race in the universe, there are infinite possibilities. There is a concept known as the Fermi Paradox, which is a contradiction between the high probability of extraterrestrial intelligence existing in the universe and the lack of evidence for such civilizations. There are a few theories that speculate on why this might be the case. Now, given the size of the universe, there’s a high probability that life exists beyond our own. And despite decades of searching and monitoring, we still have found nothing. At least nothing that the government has shared with us.

Possible explanations include the Great Filter, a barrier that prevents intelligent life from reaching a particular stage of development. Self-destruction, that’s self-explanatory. Too far away. Unrecognized signals. Or the one that scares me the most, the dark forest, which suggests that advanced civilizations are deliberately hiding to avoid destruction. There could be alien species that are close by, equivalent to or superior to our technology, and choose to remain anonymous because they’re aware of humankind’s violent nature.

It’s also possible that we’re just plain old lucky that the wrong alien species hasn’t noticed us yet. In other words, the species that would see us as a threat that has far superior technology and is willing, able, and ready to wipe us out. That’s the worst-case scenario.

10. Access! How can readers learn more about you and your works (please provide any links you want to share)?

ED: Sure, I would love to hear from my readers. Feel free to reach out to me on my website www.eddownes.com. You can also find me on Facebook, Instagram, and other social platforms. And if you enjoyed the story, please consider posting a review or sending me a selfie of you holding my book so that I can add it to my website. Pictures of my happy readers are little trophies for me, and that’s what keeps me writing!

About the Author

Ed Downes writes stories that are suspenseful, sometimes scary, and always thrilling, where things are not always what they seem. His entertaining yet vulnerable characters usually find themselves thrust into situations that appear to be no win. Ed is the author of many short thriller fiction stories including “Qalupalik,” “Regrets,” and “Dr. Bonz.“ He has recently completed his Master of Fine Arts degree in Writing Popular Fiction from Seton Hill University. A publishing industry marketing strategist by day, and novelist by night, he is a Boston native, and a lover of tennis, skiing, and scuba diving.

He currently lives in Raleigh, NC, most likely reading or writing thriller fiction or doing fun stuff with his wife Jeanie and two daughters Melissa and Jessica.

The post Interview with Author Ed Downes: Frozen Echoes appeared first on L. Andrew Cooper's Horrific Scribblings.

May 21, 2025

Interview with Author JG Faherty: The Malthusian Correction and The Nightmare People

Almost two years since our last interview, accomplished author JG Faherty checks in to discuss two horror novellas, The Malthusian Correction and The Nightmare People, both on the edge of release, very different stories but both stunning–enjoy the insights!

The Malthusian Correction (available May 27, 2025!)When Roger Brenner leaves the house because he has the urge to take a walk, no one, not even him, realizes he is about to change the world as we know it.

Roger’s sudden desire quickly turns into something more as both his mind and body begin to change. He is consumed by his need to keep walking, and soon he is leaving the small town of Rocky Point behind. By the time his family realizes he’s gone, he’s miles away and entering an altered state of consciousness.

As the days go by and Roger continues his unnatural journey, his body begins to deteriorate. He also attracts followers, all of them murmuring the same chilling phrases: “Walking” and “Must keep walking.” The growing horde travels down the East Coast, getting larger every day, with more and more of the walkers devolving into shambling, undead creatures. In less than a week, the phenomenon spreads across the world, causing religious and political upheaval. The governments fear it’s a disease. Religious leaders claim it’s a sign of the apocalypse. And scientists say it’s nature correcting overpopulation.

The same questions plague all of them:

When will it end?

And what happens next?

The world is about to find out.

Click the pic for more on Amazon!

The Nightmare People

(available June 10, 2025!)

Click the pic for more on Amazon!

The Nightmare People

(available June 10, 2025!)Forty years ago, rookie cop Bill Furman pursued suspected serial killer Arthur Blanke into the basement of Blanke’s house and witnessed something that has given him nightmares his entire life.

Blanke turning into a demon and disappearing from a locked room.

Now Furman is Chief of Police, and gruesome murders are once again rocking the small town of Moonrise Cove in North Carolina. Children and their parents torn to pieces. Other children missing. The crimes are eerily similar to the ones Arthur Blanke committed. But they also seem to have something to do with Allison Navarro’s family. Furman is aware Allison and her children survived an attack by a similar serial killer in Rocky Point, New York, twenty-five years ago. His suspicions about her family’s involvement grow stronger when Allison’s estranged son, Ken, is arrested at one of the murder scenes telling tales of a Japanese demon, the oni, being responsible.

Furman’s life is turned upside down when he and Ken come face to face with the demon and he learns that it’s been responsible not just for the deaths in Moonrise Cove and Rocky Point, but for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of deaths around the world. Because the oni is the Boogeyman of legend.

And it’s out to finish the game it started decades ago.

The Interview

The InterviewThe Malthusian Correction

1. The Malthusian. The description of The Malthusian Correction (above) overstates the unity of scientific opinion in your book, but one character does refer to population correction and the theories of the eighteenth-century political economist Reverend Thomas Malthus, named in your title. I’m only familiar with Malthus because of a very weird course I took in college. How did you come across his thinking? What gave you the idea of exploring his ideas in horror fiction? Did Malthusian thinking spark the idea for the novella, or did its inclusion come later? Either way, how did this unusual storyline take shape in your mind? To some, Malthus’s ideas might seem a little crazy… but he was a legitimate forerunner of Darwin, whom history takes much more seriously. Do you think there might be any validity to the idea that nature could “correct” overpopulation through its own devices? Why or why not?

JG: I was a biology major the latter half of my college years and also in grad school. One of the classes I took involved population modeling for an ecosystem, and we briefly touched on Malthus’s theories as they related to biological systems—like what you see in rodent populations when things get too crowded, or when predator-prey numbers get out of whack. Of course, that was 40 years ago, so I had to go back and look up some of the details to make sure I remembered things correctly.

The idea for the story didn’t come from that, though—that came from me reading the news and seeing all sorts of stories about plane crashes, wars, rising murder rates, etc., and wondering “what if all of this, the death tolls, the rising hatred and frustration we see in social media, the so-called ‘accidents,’ was really just the result of us over-populating the world? In nature, when one species gets out of control, some kind of check always balances it out. Either predator numbers increase, or the species consumes all its food sources, and starvation thins the herd. In rodents, especially mice and rats, if there are too many in a closed system (like a cage), they begin to murder and even cannibalize each other. Heck, even primate troops resort to violence when things get crowded, either killing or driving out members of the tribe.

So, once I had my plot, it was simply a matter of figuring out the basics: what tone did I want (scary, weird, action-oriented), what kind of correction would it be, and what was the outcome. And the answer came to me almost immediately. Lemmings. Now, we know that in real life, the whole idea of lemmings committing mass suicide is not really a thing. But it was perfect for my story, and since lemming suicide isn’t real, I needed a different scientific explanation. And that’s where natural correction came in, and from that the side-track of Malthus, and from that both the tone (weird) and the title.

It sounds like a lot, but I needed probably all of ten minutes to think of the plot once the idea appeared and another ten to look up the Malthus information to make sure I remembered it correctly.

As for my premise being true (nature correcting overpopulation), who knows? I do believe that overcrowding leads to violence and anger and stress. I think it’s why you see more violent crime in cities than in suburbs or the country. The more people you have jammed together, the higher the stress levels and the shorter the tempers. And in a way, rising grocery prices are the modern equivalent of natural resource shortages. Look what happens when there are empty shelves in the stores. People instantly turn feral. Most of us are one bad month, socio-economically, from going full lizard-brain.

The real question becomes, is there an overall driving force behind all this—God, Mother Nature, some higher power or almighty entity—or is it just how all things are hardwired at the most basic genetic levels? That any species will inherently do the same things in a similar situation because that’s simply how it has to be for nature to work properly?

I actually have a couple of short stories that explore this from different angles, which I hope will see the light of day (publication) in the near future.

——————

2. The Surreal. When Roger’s wife tries to communicate with him during an early phase of his walk, she experiences the interaction as “like a dream. Or an acid trip.” Readers know Roger feels “purpose” in walking, but the nature of that purpose—the motivation behind his and others’ bizarre, self-destructive behavior—remains obscure, making me feel like Roger’s wife does during that early moment through much of the story. Did you set out to create a surreal reading experience? If so, why, and what aspects other than the walkers’ bizarre behaviors contribute to the surreality? Either way, what do you think “acid trip” moments contribute to the story’s horrific impact? What does the bizarreness of what’s happening do to people in the world of the story, and what do you expect it to do to people reading the story?

JG: I absolutely wanted the entire story to feel surreal, but not in a Twilight Zone way. I was going for weird. Keep the reader guessing to the very end, yet with a few clues scattered around. I didn’t want “scary.” Not in the usual sense. In order to do that, and to make sure neither Roger’s wife nor the authorities could stop him and his followers, I had to create something that was somewhere between zombie and fanatic. One of the examples I use in the story is when Roger’s lawyer reminds people that no one blinks an eye when someone wants to walk across the US for charity or swim the English Channel or do other crazy-sounding stuff. But I also needed Roger not to be “normal” anymore. Is it a disease? Has he been taken over by a higher power? Obviously, something supernatural is at play, as we see throughout the story’s progression. But it’s slow, and by the time people realize it, the whole phenomenon is in full force.

In a way, this is an offshoot of a non-zombie, non-apocalyptic zombie apocalypse novella I wrote (along with a follow-up short story) a few years ago. It’s called December Soul (the short story is “The Lazarus Effect”). Both are in my collection Houses of the Unholy, and they describe how a growing segment of the population suddenly stops eating, stops speaking, and just starts gathering in large groups. Wherever those groups appear, more people become like them and join them. No one knows why. No one can explain how they don’t starve to death or die. But as more and more of them happen, suddenly society is in trouble because it’s breaking down. All these peaceful people just standing around or walking in big groups through the streets and parks and neighborhoods. I won’t give away the ending, but it turns out to be something other than what it seems to be.

That was another part of The Malthusian Correction that I enjoyed exploring. The idea of zombies that didn’t eat brains, weren’t violent, weren’t really zombies except that they were dead and still walking.

My hope for this story is two-fold. One, that readers are entertained. And two, after they experience the thrills and chills of the story, the chills part sticks with them and comes back each time they read the news about another plane crash or mass murder.

——————

3. Voyeuristic Frenzy. You provide a fair bit of information about the media response to the walker phenomenon, and some media representatives seem to try to prolong the phenomenon because it gets good ratings. Are you critiquing how media outlets tend to respond to unusual and potentially tragic events? Showing what you think would be a realistic response to such events? Both? What about people who come to watch the walkers as their numbers grow—does your book judge their voyeuristic curiosity? Why or why not? What’s significant about the desires to see and to know that you portray? How do they relate to your readers’ desire to “see” and know more as they read along?

JG: I think it’s a pretty realistic representation of how we’ve seen both media and onlookers react to tragic and tumultuous events. Would the media exploit something like this? Absolutely! Look at coverage for everything from storms (often blown out of proportion for days in advance), wars, politics, everything. It’s 100% about ratings now, and scooping the competition, and keeping people glued to their TVs, phones, etc. There is no journalistic integrity anymore, and even if a reporter had some, the station would either poison it or fire them.

As for the people—there would definitely be hordes of onlookers. People come from miles away to see anything unusual. Dead whale on the beach? Let’s go! Brush fires in the hills? Let’s drive past and see them. Sinkhole opens up? Plane crashes in the woods? Gotta check it out! It’s simple curiosity, and in some folks it overrides common sense. You’ve seen them. The ones that have to get right to the very edge of the Grand Canyon, where one wrong step sends them over the edge, just for the perfect selfie. The ones who stand and watch while a crime is being committed, like a bank robbery or a hostage situation, all of them right up to the edge of the police barriers. Do I think people would come watch dead people marching through town, even at the risk of becoming one? Yes, I do.

Does that relate to readers wanting to keep going with the book? No, I don’t think so. One is voyeuristic curiosity; the other is being caught up in an interesting story. Although I guess an argument could be made that the onlookers are there because in a way they’re being entertained.

——————

4. Religious Frenzy. When Roger’s wife tries to stop his walking legally on mental health grounds—he may be a danger to himself or others—people object for various reasons, particularly because he has a right to go on a religious pilgrimage even if doing so is detrimental to his health. Why are people so quick to ascribe religious significance to his seemingly inexplicable behavior? As more people join the walk, religion and public health concerns come more and more into open conflict. To what extent did similar conflicts over vaccination, particularly during the COVID crisis, influence your representation of this conflict? Does your book take a position? Why or why not? Caring for the mental health of walkers seems to be especially at odds with religious aims. How does this conflict resonate with what you see in the world outside your fiction?

JG: One of the things I’ve found about my writing is that rarely are the underlying themes or subthemes—in this case, religion vs. science, religion vs. politics, politics vs. science, etc.—part of what I have in mind when I start writing. Often, I don’t even catch them until after I’m going back to edit, or, in some cases, when reviewers mention them. That was a huge shock for me when I wrote my very first novella (The Cold Spot) back in 2012 (wow, so long ago!). In that book, I came up with the title because the main character, a kid who’d been bullied because of a birthmark on his face, discovers a cold spot in a cemetery that is from the presence of ghosts. It was only later, when a reviewer pointed things out, that I realized the title had multiple meanings. The boy’s birthmark (he’s cruelly nicknamed Spot) has turned him emotionally cold. And he’s placed in situations where the people (and ghosts) closest to him end up doing terrible things (he is in cold, hard environments).

A similar thing happened with The Malthusian Correction. I definitely wanted there to be some involvement with religious groups. How could there not be? Once it’s shown that Roger and his followers are dead but not-dead, and especially after the one scene where they should all be dead but they “return,” it’s like events from different religious tales are occurring in real life. Is it a second coming? Is Roger Jesus? Is it the apocalypse? Or, as some of the atheists and scientists proclaim, does it mean that there is no heaven, no hell, that non-death, or after-death, is simply another state of being? Do the dead have souls, or are they simply automatons?

Religious groups would be arguing like crazy. And, again reverting back to basic human nature, new religions would spring up. Humans are nothing if not predictable.

On the other hand, when it came to the health aspects of the situation (dead people marching through towns, possibly carrying deadly diseases), I had no thoughts about COVID as a key plot point. I simply went with what I thought would be a standard healthcare and military reaction to a situation like that. I’ve worked in the biological sciences, including some time working with infectious diseases, and I have friends who are virologists and bio-geneticists. Who’ve worked at the CDC or NIH. I didn’t want this book to be a statement about COVID; however, there were obviously some basic parallels because even if COVID never happened, a situation like this would still require an epidemic/pandemic-type of response at some point. Those procedures were always in place; COVID simply made more people aware of them.

——————

5. The Walking Dead. The description of your book mentions the walkers becoming “undead.” I’ll venture that it’s atypical, but how is and isn’t The Malthusian Correction a zombie story? You give Jonathan Maberry and Brian Keene cameo appearances and mention other horror along the way—what works were your major influences? Did you set out to write a fresh take on the zombie? If so, why do we need a new zombie for 2025? If not, even though the Z word is one of many conceptual frameworks people use to try to explain your walkers, how are your walkers not zombies? Why would and/or wouldn’t you want to put The Malthusian Correction in the zombie subgenre?

JG: I’ve written a lot of zombie stories, despite the fact that I don’t typically enjoy zombie stories (or movies, or TV shows). The reason I don’t usually enjoy them is they are so predictable. Slow moving zombies take over the town, or the world, or whatever. Fast moving zombies take over the town or the world, or whatever. People have to band together to stop them. Keene’s zombies were a bit different because some of them could think. Maberry’s zombie books are good in large part because he focuses more on the people than the zombies, making the terrors more realistic. But stuff like The Walking Dead, man, that gets old real fast. That series should’ve stopped after Season 3. Same with The Last of Us – it’s already reaching the point where it’s right back to the overused “warring communities” plot. (I can’t comment on either of the comic series because I don’t read comics much and haven’t since the mid-90s.)

What happens with me is that when I come up with a zombie-type story, I immediately throw it out unless it happens to take the genre in a very different direction. For instance, in “Home on the Range,” zombies are trainable and can be used as day labor and illegally as sex workers. In “Family First,” a man succumbs to a zombie bite and then wakes up to find that as long as he eats brains, he can remain a normal, fully functioning rational person, and now he has to rescue his family before the zombies get them—except the effects of brain eating only last a few hours. In “Marshal Law,” the reanimated corpses have an agenda, which you can guess from the title. In “Street Action,” zombies are part of society but there is a serious prejudice against them, and one decides to rebel. Most recently, “Mezzamort” is featured in the GabaGhoul anthology, with warring zombie mobsters as the heart of the plot.

I love taking the idea of the zombie and turning it around, twisting it into new shapes, making it something it’s not. So, as I wrote The Malthusian Correction, I consciously made sure it wouldn’t be a Walking Dead knock-off. Are Roger and his followers zombies? I guess that depends on your definition. At some point, they are dead. And they still move. If the definition of a zombie is that, then yes. But then vampires, mummies, ghouls, Frankenstein’s monster, and lots of other scary creatures would be zombies. Roger et. al. don’t eat flesh. Don’t kill anyone. Haven’t emerged from graves.

Would I put it in the zombie subgenre? Maybe, in the broadest sense.

Do we need a new zombie for 2025? Probably, and probably not. Unlike me, a lot—a real lot!—of people enjoy the tried-and-true zombies. So I think you could maybe have a new kind of zombie, but it would be in addition to the classic ones, rather than replacing them.

——————

The Nightmare People

6. Nightmare Influences. References to serial killers run through The Nightmare People. On the one hand, serial killers are a rationalization of the demonic, but on the other—are serial killers the kernel of your monster’s horror? A real serial killer, John Wayne Gacy., who killed children, gets mentioned at least once, and a fictional serial killer who kills children, Freddy Krueger, gets mentioned at least twice. In his movies, Freddy gets called “the boogeyman” and is certainly a nightmare person—how do real-life child-killing nightmare people, movie-spawned child-killing nightmare people, and your child-killing boogeyman relate? Your novella also mentions Stranger Things, a TV show in which entities from another realm repeatedly threaten kids. Your story alludes to another realm, and “Nightmare People” might refer to characters having nightmares as well as “people” monstrous enough to inspire nightmares—would you place your novella in a cluster with serial killer stories, Nightmare on Elm Street, and Stranger Things (perhaps with the horror turned up to eleven)? Why or why not?

JG: Wow, that’s a lot to unpack! Like I mentioned above, I don’t usually think about that deep stuff when I’m writing, at least not consciously. I think, for my thought process, it was more basic. If the boogeyman really did exist, it (or they) would be considered the most outrageous and prolific serial killer(s) / psychopath(s) in history. Frightening children. Stealing them. Killing them. Depending on which legend you examine, the boogeyman (or equivalent) is pretty awful.

With that in mind, I had to look at it from a cop’s point of view (because in book 1 of the trilogy, The Nightmare Man, a cop was one of the main characters, and that continues into books 2 and 3). No cop is going to believe in a supernatural serial killer. Heck, my two cops don’t, and they’ve both encountered the boogeyman! In these books, the cops do what most people would: try to rationalize what’s happening. The pop culture references, like Freddy Kreuger or John Wayne Gacy, I threw in because I think people would talk about them in conversation. The cops I know certainly would. And the manner of the deaths—the bodies being sliced up, chopped up—is reminiscent enough of horror movies to make those comparisons logical.

Imagine you’re in a dimly lit room and you see this tall, monstrous thing with long claws butcher someone. All adults know monsters don’t exist. So there’d very quickly be rationalizations. Man in a gorilla suit. Man with home-made Freddy Kreuger knife-gloves. Eventually, our heroes come to accept that there is no rational explanation except that the kids in the story are right: it’s the boogeyman. But without having seen it themselves, many of the adults, including FBI agents, learn the lesson too late.

I suppose that someone somewhere has done psychological studies about serial killers of children, people who think they’re the boogeyman, who were scarred as little kids by those stories or by being victims of serial killers or whatever. My books aren’t the place for that. I think if you start going that deep with what is essentially a horror thriller, you steal some of the inherent fear from it and it becomes more of a study object than entertainment.