Derren Brown's Blog, page 66

November 1, 2010

Fingers detect typos even when conscious brain doesn't

"Expert typists are able to zoom across the keyboard without ever thinking about which fingers are pressing the keys. New research from Vanderbilt University reveals that this skill is managed by an autopilot, one that is able to catch errors that can fool our conscious brain.

The research was published in the Oct. 29 issue of Science.

"We all know we do some things on autopilot, from walking to doing familiar tasks like making coffee and, in this study, typing. What we don't know as scientists is how people are able to control their autopilots," Gordon Logan, Centennial Professor of Psychology and lead author of the new research, said. "The remarkable thing we found is that these processes are disassociated. The hands know when the hands make an error, even when the mind does not."

To determine the relationship between the autopilot and the conscious brain, or pilot, and the role of each in detecting errors, Logan and co-author Matthew Crump designed a series of experiments to break the normal connection between what we see on the screen and what our fingers feel as they type.

In the first experiment, Logan and Crump had skilled typists type in words that appeared on the screen and then report whether or not they had made any errors. Using a computer program they created, the researchers either randomly inserted errors that the user had not made or corrected errors the user had made. They also timed the typists' typing speed, looking for the slowdown that is known to occur when one hits the wrong key. They then asked the typists to evaluate their overall performance.

The researchers found the typists generally took the blame for the errors the program had inserted and took the credit for mistakes the computer had corrected. They were fooled by the program. However, their fingers, as managed by the autopilot, were not – the typists slowed down when they actually made an error, as expected, and did not slow down when a false error appeared on the screen."

Read more at Lab Spaces (Thanks Johnny5)

A mysterious group of early humans who made tools 55,000 years ahead of their time

Blombos Cave in South Africa may have harbored a group of early humans whose tool-making techniques outpaced those of other groups by many thousands of years. Today scientists announced the discovery of more sophisticated tools from this unusually advanced civilization.

Previously, researchers have found evidence that people who lived in Blombos Cave 75,000 years ago produced jewelry and shell beads that only became common among other groups of humans roughly 30,000 to 20,000 years ago. And now a research team led by Vincent Mourre has more evidence that the people of Blombos were the high-tech civilization of the early human world.

Apparently these people invented a tool-making technique called "pressure flaking," a way of creating very sharp knives, about 55,000 years before humans elsewhere in the world did it.

Full Story over at io9

October 31, 2010

Christopher Hitchens vs. Tariq Ramadan: Is Islam a Religion of Peace?

Christopher Hitchens and Tariq Ramadan Debate: Is Islam a Religion of Peace? Moderated by Laurie Goodstein.

Via Atheist Media

Moving illusions: Impossible objects made real

"The artist M. C. Escher was renowned for creating drawings of imaginary spaces that could not exist in three dimensions. Or could they?

Kokichi Sugihara at Meiji University in Kawasaki, Japan, has been using computer software to bring impossible drawings to life. The video above shows some of the objects he has made moving in ways that appear to defy geometry.

When the models are turned around, however, the trick is revealed: the objects are not what they seem. That's because we constantly make assumptions about perspective and depth in order to move about in a 3D world, and these models take advantage of those assumptions.

Sugihara used computer software to analyse seemingly impossible drawings and come up with solid shapes that might look like the drawing from one perspective, but not from others.

It's not the first time Sugihara has tricked New Scientist readers with his illusions. Earlier this year, the engineer won first prize in the 2010 Illusion of the Year contest in Naples, Florida."

Read more at New Scientist (Thanks @XxLadyClaireXx)

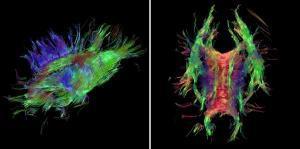

Three-Dimensional Maps of Brain Wiring

A team of researchers at the Eindhoven University of Technology has developed a software tool that physicians can use to easily study the wiring of the brains of their patients. The tool converts MRI scans using special techniques to three-dimensional images. This now makes it possible to view a total picture of the winding roads and their contacts without having to operate. Researcher Vesna Prčkovska defended her PhD thesis on this subject last week.

To know accurately where the main nerve bundles in the brain are located is of immense importance for neurosurgeons, explains Bart ter Haar Romenij (professor of Biomedical Image Analysis, at the Department of Biomedical Engineering). As an example he cites 'deep brain stimulation', with which vibration seizures in patients with Parkinson's disease can be suppressed. "With this new tool, you can determine exactly where to place the stimulation electrode in the brain.

More at Science Daily

Lies, Damned Lies, and Medical Science

"IN 2001, RUMORS were circulating in Greek hospitals that surgery residents, eager to rack up scalpel time, were falsely diagnosing hapless Albanian immigrants with appendicitis. At the University of Ioannina medical school's teaching hospital, a newly minted doctor named Athina Tatsioni was discussing the rumors with colleagues when a professor who had overheard asked her if she'd like to try to prove whether they were true—he seemed to be almost daring her. She accepted the challenge and, with the professor's and other colleagues' help, eventually produced a formal study showing that, for whatever reason, the appendices removed from patients with Albanian names in six Greek hospitals were more than three times as likely to be perfectly healthy as those removed from patients with Greek names. "It was hard to find a journal willing to publish it, but we did," recalls Tatsioni. "I also discovered that I really liked research." Good thing, because the study had actually been a sort of audition. The professor, it turned out, had been putting together a team of exceptionally brash and curious young clinicians and Ph.D.s to join him in tackling an unusual and controversial agenda.

Last spring, I sat in on one of the team's weekly meetings on the medical school's campus, which is plunked crazily across a series of sharp hills. The building in which we met, like most at the school, had the look of a barracks and was festooned with political graffiti. But the group convened in a spacious conference room that would have been at home at a Silicon Valley start-up. Sprawled around a large table were Tatsioni and eight other youngish Greek researchers and physicians who, in contrast to the pasty younger staff frequently seen in U.S. hospitals, looked like the casually glamorous cast of a television medical drama. The professor, a dapper and soft-spoken man named John Ioannidis, loosely presided.

One of the researchers, a biostatistician named Georgia Salanti, fired up a laptop and projector and started to take the group through a study she and a few colleagues were completing that asked this question: were drug companies manipulating published research to make their drugs look good? Salanti ticked off data that seemed to indicate they were, but the other team members almost immediately started interrupting. One noted that Salanti's study didn't address the fact that drug-company research wasn't measuring critically important "hard" outcomes for patients, such as survival versus death, and instead tended to measure "softer" outcomes, such as self-reported symptoms ("my chest doesn't hurt as much today"). Another pointed out that Salanti's study ignored the fact that when drug-company data seemed to show patients' health improving, the data often failed to show that the drug was responsible, or that the improvement was more than marginal."

Read more at The Atlantic (Thanks Elke)

Fingerless Robotic Hand Can Pick Anything

"A small bag filled with coffee grounds is lending robots a fingerless hand. The new kind of gripper, described online the week of October 25 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is capable of grasping all sorts of different objects with ease.

"This could be game-changing technology," says mechanical engineer Peko Hosoi of MIT, who was not involved with the new study. "The idea is so simple, yet effective and robust."

The simple gripper is made of a bag of coffee grounds and a vacuum, though other grains such as couscous and sand also work, says study coauthor Eric Brown of the University of Chicago. To pick something up, the bag of loose grounds first melds around the object. Then, as a vacuum sucks air out of the spaces between grains, the gripper stiffens, packing itself into a hard vice molded to the outline of the object. Reducing the bag's starting volume by just a teeny amount — less than 1 percent of the total — was enough to make the gripper latch on, the team found.

This transition from fluidlike behavior (such as dry sand flowing out of a bucket) to solid (a hard-packed sand castle) is a physical process called "jamming." Because the gripper's bulb conforms to any shape evenly before the vacuum jams it, it's extremely versatile. "Our goal was to pick up objects where you don't know what you're dealing with ahead of time," Brown says."

Read more at Wired (Thanks @XxLadyClaireXx)

October 30, 2010

Giant pumpkin engineer finds the secret to size

Not only does the Great Pumpkin exist, but scientists have figured out how he manages to get so big. In a sort of self-perpetuating cycle, the bigger a gourd gets, the more physical stress it experiences — thus triggering giant pumpkins to grow even more.

"Their weight generates tension, which pulls cells apart and accelerates growth," says David Hu, a mechanical engineer at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, whose team has submitted a paper to a peer-reviewed journal.

Such research doesn't just illuminate the story behind record-setting pumpkins, like the nearly 1,811-pound behemoth recognized this month by Guinness World Records. The work also addresses larger questions of plant development, such as how tissues cope under stress, Hu says.

All giant pumpkins are grown from a single strain, the Atlantic Giant seed, which has a longer growing season than normal pumpkins. The fruits start out round, but once they get to about 220 pounds, they begin to flatten under their own weight, eventually resembling a giant deflated sack.

The New York Botanical Garden, where the world's biggest pumpkin will be carved this weekend, says that a 2,000-pound pumpkin could be grown within the next few years.

Read the full story at Wired

Monet meets the internet

[image error]

A wonderfully crafted website has been put together to help announce the Monet exhibition at Les Galeries Nationales, Grand Palais in Paris. The exhibition runs from this September to January 2011. Even if you can't make it the website visit is well worth the loading time wait.

October 29, 2010

Dream recording device 'possible' researcher claims

[image error]

A US researcher says he plans to electronically record and interpret dreams. Writing in the journal Nature, scientists say they have developed a system capable of recording higher level brain activity.

"We would like to read people's dreams," says the lead scientist Dr Moran Cerf.

The aim is not to interlope, but to extend our understanding of how and why people dream. For centuries, people have been fascinated by dreams and what they might mean. In Ancient Egypt they were thought to be messages from God.

More recently, dream analysis has been used by psychologists as a tool to understand the unconscious mind. But the only way to interpret dreams is to ask people about the subject of their dreams after they had woken up.

Derren Brown's Blog

- Derren Brown's profile

- 797 followers