Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 46

October 2, 2023

a path forward

September 30, 2023

I’m with “the bloggers”

Noam Scheiber’s report on the controversies surrounding the work of Francesca Gino is … well, it’s terrible. Let me count (some of) the ways.

Let’s start with the title: “The Harvard Professor and the Bloggers.” Now, journalists typically don’t title their own pieces, but throughout the report Scheiber refers to the people who run Data Colada as “the bloggers.” The point seems to be to contrast a Figure of Recognized Authority (“the Harvard professor”) with her online critics (“the bloggers”) — a tactic reminiscent of the days when journalists sneered at people who sit around in their pajamas typing on their laptops. But these critics are also professors, at ESADE Business School in Barcelona, the Wharton School at Penn, and the Haas School of Business at UC-Berkeley. It’s only late in the report, after an extensive and fawning portrait of the suffering Professor Gino, that Scheiber acknowledges the academic credentials of those who have called attention to apparent anomalies in Gino’s research. But he still calls them “the bloggers.”

Second: Scheiber writes, “Even the bloggers, who published a four-part series laying out their case in June and a follow-up this month, have acknowledged that there is no smoking gun proving it was Dr. Gino herself who falsified data.” What does “even the bloggers” mean? There’s nothing unusual or noteworthy about “the bloggers” not directly accusing Gino of dishonesty, because that’s not what they do. They point to apparent anomalies — often, inconsistencies between (a) the conclusions drawn by scholars and (b) the data they claim to be drawing on — in research papers; it is not their job to figure out how the anomalies got there. They aren’t looking for a “smoking gun” in the hands of Professor Gino.

In general, Scheiber seems to have seen it as his job to take up Gino’s sense of outrage. He says very strange things, like “She did not present as a fraud.” Well, of course. One cannot succeed in deceiving people if one presents as a fraud. The statement is an irrelevance. Similarly, Scheiber says that Gino often provided “a plausible answer” when he questioned her. But what his questions were, what her answers were, why he found them plausible, and how all that relates to the evidence provided at Data Colada — we’re not told any of that.

Finally: Scheiber seems not to have asked what, to me, would be the single most obvious question: Why is she suing “the bloggers”? Apparently the cause is “defamation,” but how does the think they have defamed her simply by pointing to anomalies in her published research papers? The closest Scheiber comes to approaching the issue is in this passage:

… the bloggers publicly revealed their evidence: In the sign-at-the-top paper, a digital record in an Excel file posted by Dr. Gino indicated that data points were moved from one row to another in a way that reinforced the study’s result.

Dr. Gino now saw the blog in more sinister terms. She has cited examples of how Excel’s digital record is not a reliable guide to how data may have been moved.

“What I’ve learned is that it’s super risky to jump to conclusions without the complete evidence,” she told me.

Nothing about this makes sense. First of all, what is “sinister” about noting a manipulation of data in an Excel sheet? If that’s wrong, what’s wrong about it? What “conclusions” did the Data Colada investigation “jump to”? And above all, even if all of her criticisms are correct, why not offer a rational refutation rather than file a lawsuit? Suing her employer, Harvard, makes obvious sense, since Harvard has suspended her from her job without pay and is seeking to revoke her tenure. Faced with similar circumstances I might also sue. But suing people for writing that the data meant to support certain conclusions seems to have been manipulated by person or persons unknown? That requires some explanation.

Scheiber doesn’t ask any of these questions. He’s not interested in anything except a profile of a wounded person. But I agree with the lawyer for “the bloggers” who says that such a lawsuit is “a direct attack on academic inquiry.” What Gino is doing certainly looks like a straightforward attempt to intimidate into silence anyone who might ask hard questions about her research. I came away from Scheiber’s pseudo-inquiry thinking that I need to contribute to Data Colada’s legal defense fund. I don’t believe that’s what Scheiber intended.

September 29, 2023

Auden, fifty years later

W. H. Auden died fifty years ago today.

He is the single most important writer and thinker in my life, and has been ever since, in my very last class in graduate school, I read his collection of essays The Dyer’s Hand. (Though it’s more than a collection of essays: it’s Auden’s Ars Poetica or Biographia Literaria.) The prose led me to the poetry and then there was no going back.

I wrote my first book (a book that had a peculiar route to publication) about Auden, featured him as one of the central figures in my The Year of Our Lord 1943, and have now produced three critical editions of his books: The Age of Anxiety, For the Time Being, and (forthcoming) The Shield of Achilles.

Some of my essays and reviews about Auden available online:

“Auden and the Dream of Public Poetry” “The Poet’s Prose” “Auden and the Limits of Poetry” “Sandfield Road” (an imaginary conversation) “The Love Feast” (a review of the Complete Poems) There are many posts on Auden here on this blog — see the tag at the bottom of this post — but this is one of the more important ones.He was, shall we say, quite a character, and the anecdotes about him — about his titanic messiness and equally exceptional kindness — may readily be found. I do wish I had known him personally, but his work is so filled with his distinctive personality that I always feel that I do.

Auden has done more than anyone else to help me understand what it means to be a Christian in my own moment — one neither hankering after a vague Utopia or pining for an illusory lost Arcadia. In poetry and prose alike, he has given me great pleasure and inexhaustible food for thought. One of the great themes of his work is the necessity and the blessing of gratitude, and thus he has been my primary instructor in how to be grateful. Today, especially, I am grateful for him.

September 28, 2023

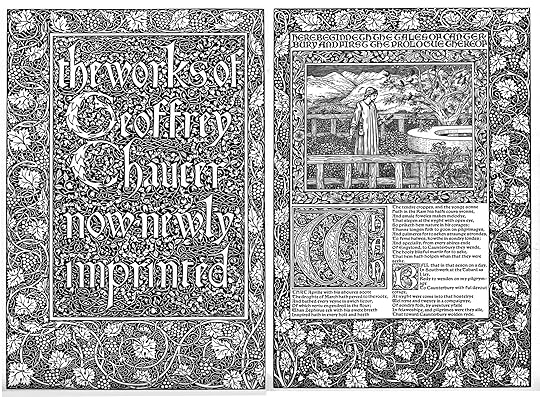

Michael John Goodman:For me (though I am sure others will...

For me (though I am sure others will disagree!), the artistic power of the Kelmscott Chaucer is in the harmonious balance that is achieved between Burne-Jones’ illustrations and Morris’ frames, borders, typography and the visually striking double-page spreads. And users can investigate each of these aspects individually in turn on the website. The decision to make it a primarily visual experience is both practical and editorial. Practically, it just would not be worth the time and effort to digitize nearly 600 pages, especially when the complete works of Chaucer are available for anyone to read almost everywhere and for very cheap. Even if this aim was desirable and could have been achieved efficiently, it would have changed the very nature of the project, bloating it out into a project where the focus became so broad that the visual aspects would have become, if not diluted, then certainly more obscured amongst a sea of similar-looking text-based pages.

September 27, 2023

department of corrections

danah boyd: “Over the last two years, I’ve been intentionally purchasing and reading books that are banned.” The problem here is that none, literally not one, of the books on the list boyd links to have been banned. Neither have they been “censored,” which is what the article linked to says. That’s why boyd can buy and read them: because they’ve been neither banned nor censored.

What has happened is this: Some parents want school libraries to remove from their shelves books that they (the parents) think are inappropriate for their children to read. You may think that such behavior is mean-spirited or otherwise misconceived — very often it is! — but has nothing to do with either banning or censorship.

But, of course, the American Library Association has been quite effective in redefining the words “banning” and “censorship” to include actions that are far less drastic — less drastic and not especially common: as Micah Mattix has documented here and here, there simply is no widespread movement to keep books off school library shelves.

In a sane world, the term “ban” would be reserved for books whose sale and circulation are illegal in some given place, and “censorship” would refer to the removal, by some legal or commercial authority, of certain portions of a text or film or recording. (I say “commercial” authority because sometimes companies that own the rights to works of art decide, without legal pressure, to delete some lyrics in a song or change certain words in a book.) But thanks to people who want to smear their RCOs, it is now common to use precisely the same words to describe (a) what the nation of Iran did to Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses and (b) a polite letter from a parent to a school librarian asking that books that offer anatomically detailed descriptions of sexual practices not be readily available to third graders. Of course, many concerned parents are not polite, but polite letters on this topic still count, for the ALA, as a “challenge,” and the organization defines a challenge as an attempt at censorship or banning.

This failure to make elementary distinctions is neither politically nor intellectually healthy.

I sometimes wonder whether this kerfuffle isn’t something of a smokescreen, intended to distract our attention from more serious and troubling attempts at what George Orwell called “the prevention of literature” — for instance, removing books from sale altogether, pulping offensive books, or ensuring that they aren’t published at all. (In some cases that means that the authors aren’t published at all.) You can buy books that some parents have protested; you can’t buy books that, because of political pressure, have never seen the light of day. So you know what I’m craving today? A little perspective.

September 25, 2023

my testimony

This is an except from my least-read book, a small treatise on narrative theology called Looking Before and After . Much of the book concerns the question of what it means, if it means anything coherent, to say that I have a “life story.” At one point I tell a bit of my own story, as I understand it, and that’s what follows.

The summer before I was to begin high school, my family moved from one end of Birmingham, Alabama, to another. “Zoning” had begun in Birmingham a few years before, and had we remained in our old neighborhood I would have been one of ten or so white students in a high school with a total population of more than a thousand. My parents didn’t believe that would be such a good thing for their son, so we moved to an all-white neighborhood within the “zone” of a mostly white school. My parents considered that the move encouraged fresh starts in other ways too, so within a few weeks they had picked out a nearby church, 85th Street Baptist, and we became fairly regular attendees — at least on Sunday mornings. (Sunday evening services or Wednesday prayer meetings remained well beyond the scope of our discipline.) This lasted only about a year before we lapsed back into our old habits of rare attendance, but in the meantime I got myself saved. Or so I think.

Southern churches — I have learned that this is a source of amusement to many of my fellow Christians from outside the South — often schedule revivals, bringing in guest evangelists to stir up the faithless and backslidden. But even with a revival a week away, our pastor, Brother McKee, still conducted his usual invitation at the end of the Sunday morning service. (I was an adult living in the Midwest before I ever heard the term “altar call.”) I had sat throughout the service with my friends, giggling and whispering as usual, and in silent moments doodling on the little magazine of devotional articles for teenagers that had been handed out in Sunday school an hour earlier and for which I was always thankful, since it provided fifteen minutes or so of distraction. The sermon eluded my attention, but I stood up with everyone else as the choir sang “Softly and Tenderly” — or perhaps it was “Just As I Am.” I was thirteen years old.

At that moment the Holy Spirit, with overwhelming force, called me to walk down the aisle and make my profession of faith. My will was clearly being commanded by something not me — something I knew could only be God. When, years later, I read John Wesley’s account of how in a meeting his heart was “strangely warmed,” I thought I knew just what he meant: I seemed for those moments to be heated from within. I had never experienced anything remotely like it before; nor, I must say, have I since. It was all I could do not to run down the aisle; but I did not run down the aisle. In fact, I remained fixed in my place. I stood as the choir and congregation sang, gripping the pew in front of me fiercely — I can see even now, in my mind’s eye, my knuckles going white with the effort of restraining myself from flying toward the pastor.

I was ashamed. I knew that I had paid no attention during the service, that I had snickered with my friends, and I feared their mocking judgment and that of any adult observers of my antics. I felt certain that if I walked down the aisle and “made my profession of faith,” everyone would be puzzled — they would wonder if I was joking, or, worse, mocking. So I stayed rooted at my pew.

Nevertheless, the experience shook me. I tried all week to forget it and was able occasionally to put it from my mind; but I could not pretend that I had any other explanation for what had happened to me — I knew that the power that had invaded me was not me, and I knew its real name. The sense of being strangely warmed remained with me through the week.

The following Sunday, as I walked once more with my parents into the church, a large banner outside proclaimed that the revival would begin that evening. Our pastor’s sermon topic, in his last message before the revival, was an interesting one: he said that sometimes God gives you only one chance to repent; we cannot presume upon his grace, we cannot count on His offering endlessly repeated opportunities to turn aside from our evil ways and dark paths. He told a story about a young man who rejected an opportunity to repent and was almost immediately thereafter struck by a car and killed — not as punishment, mind you: it was just that the fellow’s time was up, and he had wasted all of his chances.

The service drew to a close; we sang a final hymn; and Brother McKee did not issue an invitation, but merely dismissed us with a prayer and a reminder of the evening service.

At home, over lunch, I told my parents that I thought I would like to go to the revival that evening. They looked blankly at me. My father shrugged; my mother said, “Well, good for you.” I walked the eight blocks to the church, taking extreme care when crossing streets; I arrived early and took a seat on the right side, in the second row. I heard as little of this sermon as I had of the one preceding my unexpected Call, though for very different reasons. When the preacher began to intone the familiar words of invitation from what I now think of as the Southern Baptist revival liturgy — “with every head bowed and every eye closed” — and asked for a show of hands from those interested in repenting, my arm shot upward. At the first opportunity I bolted for the front. A few Sunday evenings later I was baptized.

And that was all. I had my insurance; if I wandered into the street and got hit by a car, I would be OK. Before long we stopped going to church. I gave God no thought for another six years.

September 20, 2023

The Child of Nature and the Citizen

Francois Truffaut’s The Wild Child is a truly remarkable movie that has never gotten the attention it deserves. And so I’m going to begin this post by saying that (a) it deserves a place in the Criterion Collection and (b) I hereby volunteer to write an essay introducing it. (Actually, my suspicion is that Criterion would’ve created such an edition a long time ago if they had been able to get the rights.)

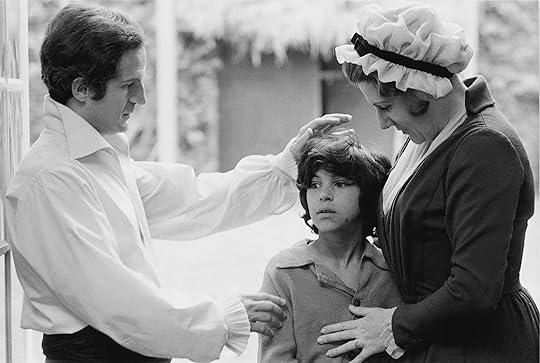

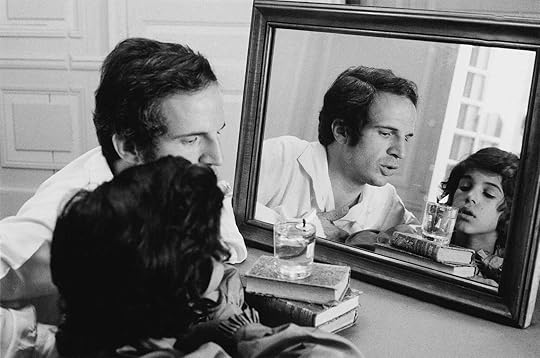

The movie’s story is based on a historical event, the discovery of the so-called Wild Boy of Aveyron and the attempts of a physician named Jean Marc Itard — played in the movie by Truffaut himself — to educate him. One tiny, easily-missed element of Truffaut’s version of the story provides what I believe is the key that unlocks the whole narrative.

Occasionally Dr. Itard takes Victor (as he names the child) to visit some friends of his who live on a farm. We’re never told why, but the obvious suggestion would be that their rural life is for Victor a return to something like the open, free, “natural” life that he lived before he was discovered. Dr. Itard and his friend sit inside and play backgammon while — we see this sometimes through an open door — the friend’s child pushes Victor in a wheelbarrow.

But the key point is that Itard consistently refers to his friend as Citoyen — which reminds us, and is very much meant to remind us, that these events are unfolding in the aftermath of the French Revolution. That is to say, the Wild Boy was discovered within the country that had gone further than any other in ordering itself by the inexorable strictures of Reason. This, I think, is the primary source of Truffaut’s interest in the story. He is fascinated by the contrast between two models of ideal humanity: on the one hand, the Natural Man uncorrupted by society; and on the other hand, the Citoyen governed by pure Raison — reason understood as requiring the elimination of the church, the proposed redrawing of the departments of France into geometric forms, the renaming of the months and regularizing of the calendar, and so on. As Simon Schama has convincingly argued, “If one had to look for one indisputable story of transformation in the French Revolution, it would be the creation of the juridical entity of the citizen.”

(Not germane to this particular post, but it’s perhaps worth saying that the combination of this emphasis on the universal equality of citizens with the determination to overcome Nature with Reason helps explain the profound ambivalence of the Revolutionaries towards Rousseau: in many ways he lays the groundwork for the Revolutionaries’ political project while utterly repudiating their understanding of human nature.)

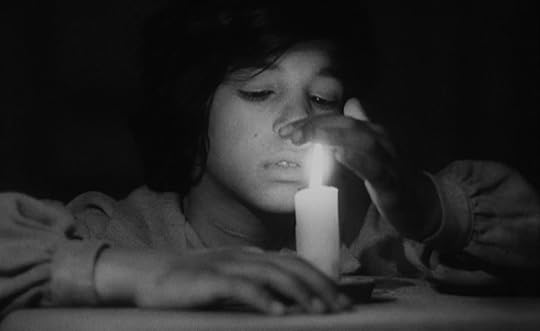

These two images are placed side by side, in fierce opposition to each other. And thus the most interesting character in the movie is not Victor — though he is fascinating, as played by the young Romani boy Jean-Pierre Cargol, who is compelling throughout — but rather Dr. Itard himself. Throughout the story the good physician is quietly torn between his desire to “transform” Victor into a rational man, a potential Citoyen, and his natural compassion. At times he treats Victor with a harshness that he hates to perform, but he does so anyway, because he believes that he is acting in accordance with the demands of reason. After all, the stakes for Victor are so very high. Schama again:

Suddenly, subjects were told they had become Citizens; an aggregate of subjects held in place by injustice and intimidation had become a Nation. From this new thing, this nation of citizens, justice, freedom and plenty could be not only expected but required. By the same token, should it not materialize, only those who had spurned their citizenship, or who were by their birth or unrepentant beliefs in capable of exercising, yet, could be held responsible. Before the promise of 1789 could be realized, then, it was necessary to root out Uncitizens.

Dr. Itard could not allow Victor to become, or rather to remain, an Uncitizen.

All his life Truffaut was fascinated by wayward children and outraged by the social structures devised to control them. He himself had always struggled in school and spent much of his adolescence bouncing between school and institutions for “troubled youth.” He dramatized his experiences in his first feature, The 400 Blows, and returned to such themes often in his later films. (In this post I mention Truffaut’s interest in a man named Fernand Deligny, who devised imaginative ways of aiding neurodivergent children. Truffaut had consulted with Deligny in making The 400 Blows and consulted him again when making The Wild Child.)

As Truffaut sees it, French society’s standard way of dealing with difficult children can be summed up in two words: Discipline and Punish. The whole strategy is one of negative reinforcement, and the most touching thing about Dr. Itard is that he is an immensely kind man who, thanks to his intellectual formation, has only those tools at his disposal. His own character — his own nature, we might say — is at odds with his professional commitments. As a physician he is a Skinnerian avant le lettre, believing that Victor can be turned into a rational man and potential Citoyen simply through operant conditioning. He doesn’t seem to realize that what Victor craves is affection. He loves to touch and to be touched. And while Dr. Itard does not by any means withhold such touch from him — he often holds his shoulders or embraces him — he does not realize how essential such physical affection is to Victor’s upbringing and improvement.

What is essential, for Dr. Itard, is to constrain Victor’s nature — to bring it, as it were, within a frame, and here we should notice how many scenes in the movie are framed by windows and doors. Sometimes we are on the outside looking in, and sometimes on the inside looking out. Sometimes the frames are multiple, especially when we consider that the cinematic image constitutes its own frame. There’s an extraordinary moment early on when the still-wild boy climbs a tree to escape some pursuers, and the camera, positioned at the height of the forest canopy, pulls back to show the boy in this vast unbounded wilderness. But when he is brought to Paris, and then to Dr. Itard’s house on the outskirts of Paris, he is surrounded by right angles that enclose small spaces.

(This distinction is powerfully dramatized through the magnificent photography of the great Nestor Almendros, who in the wilderness scenes gives us a world of light and shade captured fleetingly by a moving camera, while in Dr. Itard’s house all is still and lit with a Vermeer-like gentleness and evenness. This movie should be on anyone’s short list of masterworks of black-and-white cinematography.)

Near the end of the movie, Victor, frustrated by Dr. Itard’s rigid and incessant lessons in the rational order of language, runs away, and finds himself once more in a State of Nature. But, after a brief period of delighting in his freedom, he discovers, or rediscovers, that human life in the State of Nature is pretty much what Hobbes said it was: “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Victor struggles to find food: because he is now in a place that is at least sparsely populated, and perhaps because he has forgotten some of the skills that he had developed when living alone in the wild, he finds his primary option is theft — and theft is both difficult and dangerous. So eventually he returns to Dr. Itard.

Dr. Itard is thrilled to have him back and sees this return as a sign that his program is working, that Victor is becoming more rational. And so as Madame Guérin — the kindly housekeeper, who had already warned the doctor about his overly harsh methods — leads Victor up the stairs to get him a bath and a change of clothes, Dr. Itard cheerfully calls out to Victor, “We will resume our lessons tomorrow!” And in the very last shot of the movie, Victor looks back at his benefactor — or his jailer — with an utterly inscrutable expression on his face. You might perceive it as obedient, or sullen, or resentful, or even hateful. It’s impossible to say. Victor still cannot speak. But he surely knows he has given up his freedom, his wildness, for a civilized life. In a civilized world, he has safety, and cleanliness, and food, and even companionship and affection. These are all wonderful things, great achievements of the kind of social order that ultimately produces Citoyens. But he can’t seem ever to forget the very different world that he has left behind; nor can we. This finely-poised ambivalence is the essential achievement of a very great film.

September 18, 2023

a silent adventure

Whenever people speak in L’Avventura I find their talk intrusive. I imagine a Phantom Edit of the movie that removes all the scenes in which people speak, and in which all sounds are replaced by one of Eno’s ambient compositions, so I could then contemplate the evocative images without distraction.

September 16, 2023

A letter from François Truffaut to Jean Renoir, telling t...

A letter from François Truffaut to Jean Renoir, telling the old master how much The Rules of the Game meant to him. Truffaut had lovely handwriting, I think, and made use of it in The Wild Child, where we see him, as Dr. Itard, writing in a journal about Victor’s progress, or lack thereof.

Truffaut wrote thousands and thousands of letters; he seems to have found it easier to speak his mind, and heart, in letters than in either phone calls or face-to-face meetings. Had he lived in the Age of Email I am certain that he would have continued to communicate by handwriting.

gardening strategies

I love this by John Holt, transcribed by my buddy Austin Kleon:

You learn to teach by teaching. I never had any educational training, luckily. I say “luckily” because I went into the classroom knowing that I didn’t know anything, and therefore realizing that if I wanted to learn something, I’d better keep my eyes and ears open and think about what I was seeing and hearing. The only way you learn about teaching is to do it and to see which of your inputs into this environment produce helpful results and which don’t, and maybe to talk about your problems with other teachers and say, “How are you making out?”

I would just add one point: What you can do might be something different than what another teacher can do.

Many years ago, I was asked to observe the teaching of one of my colleagues, Christina Bieber Lake. I walked into her classroom, saw 32 students, and thought Hmmm, I wonder how she’s going to handle this. I thought that because I knew that Christina strongly preferred leading discussions to lecturing, and how do you manage a discussion with that many people in the room?

The answer was: Easily. The conversation flowed both smoothly and energetically, and in the one-hour-plus-change that I sat in the back of the room, 27 of the 32 students spoke up — without prompting. I think my jaw literally dropped. My first thought was: I want to teach that way.

But upon some reflection I had a second thought: I don’t think I can teach that way. I realized that just don’t have the skills, or, maybe more accurately, the feel for the thing. Now, to be sure, I knew I could be better at leading discussions. But I wasn’t going to be a better teacher by trying to imitate Christina, even if I could learn from her.

I often think of something Bob Dylan once said:

I’d like to drive a race car on the Indianapolis track. I’d like to kick a field goal in an NFL football game. I’d like to be able to hit a hundred-mile-an-hour baseball. But you have to know your place. There might be some things that are beyond your talents. Everything worth doing takes time. You have to write a hundred bad songs before you write one good one. And you have to sacrifice a lot of things that you might not be prepared for. Like it or not, you are in this alone and have to follow your own star.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers