Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 45

October 19, 2023

Ida York Abelman, “Man and Machine”

Ida York Abelman, “Man and Machine”

October 18, 2023

diseases of the intellect

Twenty years ago, I had an exceptionally intelligent student who was a passionate defender of and advocate for Saddam Hussein. She wanted me to denounce the American invasion of Iraq, which I was willing to do — though not in precisely the terms that she demanded, because she wanted me to do so on the ground that Saddam Hussein was a generous and beneficent ruler of his people. That is, her denunciation of America as the Bad Guy was inextricably connected with her belief that there simply had to be on the other side a Good Guy. The notion that the American invasion was wrong but also that Saddam Hussein’s tyrannical rule was indefensible — that pair of concepts she could not simultaneously entertain. Because there can’t be any stories with no Good Guys … can there?

This student was not a bad person — she was, indeed, a highly compassionate person, and deeply committed to justice. She was not morally corrupt. But she was, I think, suffering from a disease of the intellect.

What do I mean by that? Everyone’s habitus includes, as part of its basic equipment, a general conceptual frame, a mental model of the world that serves to organize our experience. Within this model we all have what Kenneth Burke called terministic screens, but also conceptual screens which allow us to employ key terms in some contexts while making them unavailable in others. We will not be forbidden to use a word like “compassion” in responding to our Friends, but it will not occur to us to use it when responding to our Enemies. (Paging Carl Schmitt.)

My student’s conceptual screens made certain moral descriptions — for instance, saying that a particular politician or action is “cruel” or “tyrannical” — necessary when describing President Bush but unavailable when describing Saddam Hussein. But I seriously doubt that this distinction ever presented itself to her conscious mind. It worked in the background to determine which thoughts were allowed to rise to conscious awareness and therefore become a matter for debate. To return to a distinction that, drawing on Leszek Kołakowski, I have made before, the elements of our conceptual screens that can rise to consciousness belong to the “technological core” of human experience, while those that remain invisible (repressed, a Freudian would say) belong to the “mythical core.”

I could see these patterns of screening in my student; I cannot see them in myself, even though I know that everything I have said applies to me just as completely as it applies to her, if not more so.

Certain writers are highly concerned with these mental states, and the genre in which they tend to describe them is called the Menippean satire. (That link is to a post of mine on C. S. Lewis as a notable writer in this genre, though this has rarely been recognized.) In his Anatomy of Criticism, Northrop Frye wrote,

The Menippean satire deals less with people as such than with mental attitudes. Pedants, bigots, cranks, parvenus, virtuosi, enthusiasts, rapacious and incompetent professional men of all kinds, are handled in terms of their occupational approach to life as distinct from their social behavior. The Menippean satire thus resembles the confession in its ability to handle abstract ideas and theories, and differs from the novel in its characterization, which is stylized rather than naturalistic, and presents people as mouthpieces of the ideas they represent…. The novelist sees evil and folly as social diseases, but the Menippean satirist sees them as diseases of the intellect. [p. 309]

Thus the title of my post.

I think much of our current political discourse is generated and sustained by such screening, screening that an age of social media makes at once more necessary and more pathological. Also more universally “occupational,” because in some arena of our society — journalism and the academy especially — the deployment of the correct conceptual screens becomes one’s occupational duty, and any failure so to maintain can result in an ostracism that is both social and professional. And that’s how people, and not just fictional characters, become “mouthpieces of the ideas they represent.”

None of this is hard to see in some general and abstract sense, but it’s hard to see clearly. What Lewis calls the “Inner Ring” is largely concerned to enforce the correct conceptual screens, and because those screens don’t rise to conscious awareness, much less open statement, the work of enforcement tends to be indirect and subtle, and perhaps for that very reason irresistible. It’s like being subject to gravity.

In certain cases the stress of maintaining such conceptual screens grows to be too much for a person; the strain of cognitive dissonance becomes disabling. Crises in one’s conceptual screening, as Mikhail Bakhtin wrote in Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, were of particular interest to Dostoevsky:

In the menippea there appears for the first time what might be called moral-psychological experimentation: a representation of the unusual, abnormal moral and psychic states of man — insanity of all sorts (the theme of the maniac), split personality, unrestrained daydreaming, unusual dreams, passions bordering on madness, suicides, and so forth. These phenomena do not function narrowly in the menippea as mere themes, but have a formal generic significance. Dreams, daydreams, insanity destroy the epic and tragic wholeness of a person and his fate: the possibilities of another person and another life are revealed in him, he loses his finalized quality and ceases to mean only one thing; he ceases to coincide with himself. [pp. 116-19]

This deserves at least a post of its own. But in general it’s surprising how powerful people’s conceptual screens are, how impervious to attack. But maybe it shouldn’t be surprising, since those screens are the primary tools that enable us to “mean only one thing” to ourselves; they allow us to coincide with ourselves in ways that soothe and satisfy. The functions of the conceptual screens are at once social and personal.

All this helps to explain why the whole of our public discourse on Israel and Palestine is so fraught: the people participating in it are drawing upon some of their most fundamental conceptual screens, whether those screens involve words like “colonialism” or words like “pogrom.” But this of course also makes rational conversation and debate nearly impossible. The one thing that might help our fraying social fabric is an understanding that, when people are wrong about such matters — and that includes you and me —, the wrongness is typically not an indication of moral corruption but rather the product of a disease of the intellect.

And we all live in a social order whose leading institutions deliberately infect us with those diseases and work hard to create variants that are as infectious as possible. So my curse is straightforwardly upon them.

I don’t want to pretend that I am above the fray here. I have Opinions about the war, pretty strong ones at that, and I have sat on this post for a week or so, hemming and hawing about whether I have an obligation to state my position, given the sheer human gravity of the situation. But while I’m not wholly ignorant, I don’t think that my Opinions are especially well-informed, and if I put them before my readers — well, I feel that that would be presumptuous. (Even though I live in an era in which most people find it disturbing or even perverse if you hold views without proclaiming them.) There are thousands of writers you could read to find stronger and better-informed arguments than any I could make.

But I do think I can recognize and diagnose diseases of the intellect when I see them. That’s maybe the only contribution I can make to this horrifying mess of a situation, and I’m counting on its being more useful if it isn’t accompanied by a statement of position.

I hope this won’t be taken as a plague-on-both-your-houses argument, though I’m sure it will. (I have made such arguments about some things in the past, but I am not making one here.) When you write, as I do above, about the problem with a conceptual screen that requires one purely innocent party and one purely guilty party, you will surely be accused of “false equivalency” or “blaming the victim.” But you don’t have to say that a person, or a nation, or a people is utterly spotless in order to see them as truly victimized. Sometimes a person or a nation or a people is, to borrow King Lear’s phrase, “more sinned against than sinning” without being sinless. And I think that applies no matter what role you assign to which party in the current disaster.

With all that said, here are some concluding thoughts:

A monolithic focus on assigning blame to one party while completely exonerating the other party is a sign of a conceptual screen working at high intensity. Such a monolithic focus on blame-assignation is also incapable of ameliorating suffering or preventing it in the future. (Note the use of the italicized adjective in these two points: the proper assessment of blame is not a useless thing, but it’s never the only thing, and it is rarely the most important thing, for observers to do.) If you are consumed with rage at anyone who does not assign blame as you do, that indicates two things: (a) you have a mistaken belief that disagreement with you is a sign of moral corruption, and (b) your conceptual screen is under great stress and is consequently overheating. It is more important, even if it’s infinitely harder, for you to discover and comprehend your own conceptual screens that for you to see the screens at work in another’s mind. And it is important not just because it’s good for you to have self-knowledge, but also because our competing conceptual screens are regularly interfering with our ability to develop practices and policies that ameliorate current suffering and prevent future suffering. A possible strategy: When you’re talking with someone who says “Party X is wholly at fault here,” simply waive the point. Say: “Fine. I won’t argue. So what do we do now?” Then you might begin to get somewhere — though you’re more likely to discover that your interlocutor’s ideas begin and end with the assigning of blame.October 16, 2023

Mark C. Taylor:

I do not think human beings are the last ...

I do not think human beings are the last stage in the evolutionary process. Whatever comes next will be neither simply organic nor simply machinic but will be the result of the increasingly symbiotic relationship between human beings and technology.

Bound together as parasite/host, neither people nor technologies can exist apart from the other because they are constitutive prostheses of each other.

But which one’s the parasite and which the host? Add odd point to be omitted, considering its importance.

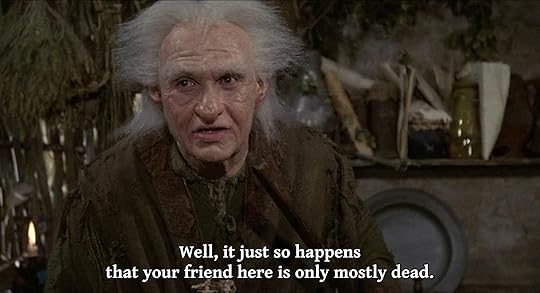

only mostly dead

The other day I wrote about the absolute cataract of essays and articles these days proclaiming the death of something — something, anything, everything: capitalism, liberalism, Trumpism, tradition, conservatism, the novel, poetry, movies … the list goes on and on.

Today I’m wondering how much this habit of mind arises from an economic system built around planned obsolescence and unrepairable devices. If we are deeply habituated to throwing away a bought object when it is no longer performing excellently, then why not do the same with ideas? Hey, this thing I believe in no longer commands universal assent. Let’s flush it.

And for that matter why not take the same approach to people? If you’re in Canada and having suicidal thoughts, then you just might have a counselor suggest medically-assisted suicide. You’re hardly worth repairing, are you? Let’s just ease you into death and get you off our books.

It shouldn’t take a Miracle Max to tell the difference between dead and mostly dead, which is also slightly alive. But our social order can’t even tell the difference between dead and imperfect — because the Overlords of Technopoly profit when that distinction is unavailable to us. And we should always remember that when someone declares that one object or idea is dead, they’re probably quite ready to sell us a new one.

Where there’s life, there’s hope; and where there’s hope, there’s the imperative to repair. Technopoly is a system of despair.

October 12, 2023

begin here

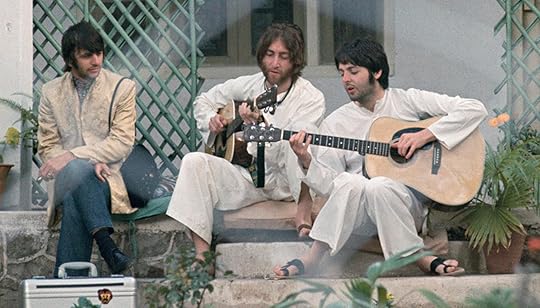

The essay that I published earlier this year on “Resistance In the Arts” was largely inspired by my reading of one book, Ian MacDonald’s simultaneously maddening and magisterial Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties. It’s important to to pay attention to that subtitle. McDonald wants to argue that the music that the Beatles made exemplifies the cultural movement that we call “the Sixties” better than anything else does, and he makes a very good case for that idea, in which I’m quite interested. But I’m even more interested in the final words of the actual narrative of the book, words written by way of introduction to a chronology of the 1960s. (That chronology, which serves as an appendix to the book, consists of four columns: what the Beatles were doing; what else was happening in pop music in the UK; key political and social events; and developments in the arts more generally — for instance, cinema, jazz, classical music, poetry, etc.) Here’s what MacDonald says to conclude his narrative and introduce that chronology:

There is a great deal more to be said about the catastrophic decline of pop (and rock criticism) — but not here. All that matters is that, when examining the following Chronology of Sixties pop, readers are aware that they are looking at something on a higher scale of achievement than today’s — music which no contemporary artist can claim to match in feeling, variety, formal invention, and sheer out-of-the-blue inspiration. That the same can be said of other musical forms — most obviously classical and jazz — confirms that something in the soul of Western culture began to die during the late Sixties. Arguably pop music, as measured by the singles charts, peaked in 1966, thereafter beginning a shallow decline in overall quality which was already steepening by 1970. While some may date this tail-off to a little later, only the soulless or tone-deaf will refuse to admit any decline at all. Those with ears to hear, let them hear.

So that’s MacDonald’s blunt assessment. And what launched my essay was a double response to that paragraph. On the one hand, I thought that in relation to pop music, he is 100% correct. But the sweeping judgment I have highlighted, about “the soul of Western culture,” is less readily defensible. He wrote those words in the mid or late 1990s. In retrospect, it seems to me that classical music was in a much, much better place in the 1990s than it had been in the 1960s; similarly, the architecture of the Nineties was significantly more varied and inventive than architecture in the Sixties, partly as a result of certain technical changes, including CAD (computer-assisted design). I could give other examples.

Thus MacDonald’s Grand Narrative about Western culture — his assumption that Western culture is one giant, uniform Thing that is always on a single trajectory, either ascending or descending — is just nonsense, if also an all-too-common form of nonsense.

But: at any given moment in history in any given location, certain specific arts may operate at a higher level than they do at other times, or in other places. So I began my essay by noting how much better English drama was in the period between 1590 and 1620 than it ever had been before or ever would be again — and that is true even if you factor Shakespeare out of the equation. (You still have Marlowe, Webster, Jonson, Beaumont & Fletcher, etc.) Ditto the outpouring of genius in pop music between, say, 1962 and 1975, an outpouring that’s astonishing even if you factor the Beatles out of the equation. And what such stories suggest, or anyway what they suggest to me, is that circumstances can conspire to make a particular art form more dynamic at some moments than it is at others.

I’m not sure that I made myself perfectly clear in that essay. I’m a bit frustrated with it. But I still think that the chief point that I was pursuing is an absolutely vital one. We need to think about what kinds of circumstances encourage outstanding art and what kinds militate against outstanding art. In the essay I argued that there must be a balance between forces that enable and forces that resist, and that that balance is at once technological, economic, and social. You have to be able to do and make certain things, but the making should not be too easy, just as you should not be totally blocked from achieving what you’re trying to achieve. I mentioned the Beatles song “Tomorrow Never Knows,” which creates special effects through the use of five tape loops, loops which are placed within the song in a cunningly designed sequence. The loops (made by Paul McCartney on a tape recorder he had at home) were not easy to create, which is why there were only five of them; but five turned out to be the perfect number, because that allowed both repetition and variation, both of which are key to successful art. Moreover, while the Beatles were free to add those tape loops to the song, they were not (yet) free to spend six months in the studio or to make 10-minute songs.

The Beatles were immensely talented, to be sure, and were surrounded by equally talented support in the producer George Martin and the engineer Geoff Emerick; but Taylor Swift is also extremely talented and knows how to surround herself with gifted producers, engineers, and musicians, and yet, for all her enormous popularity, she isn’t changing the face of music. Her musical language is basic and predictable: given any two consecutive chords of a Swift song, the listener can predict with a high degree of confidence what the next one will be. She has not, to my knowledge, written or performed a single song that alters even in the tiniest way the landscape of pop music, while, by contrast, there was a period of five years during which the Beatles were doing that every few weeks. Maybe those conditions simply can’t be recreated; maybe Taylor Swift, and indeed everyone working in the aftermath of the Beatles’ meteoric career, is, in Harold Bloom’s term, belated. But, on the other hand, maybe we’re too quick to accept belatedness.

One of the reasons we still listen to the Beatles (one of the reasons we still read or watch Shakespeare) is that for them, in their time and place, they discovered the ideal balance between enablement and resistance; the stars aligned for them. (When the Beatles broke up the stars went out of alignment, forever; even if John Lennon had lived and the band had reassembled, they wouldn’t have been able to come close to what they achieved in the Sixties. The balance of resistances had altered, and for the worse.) I tried — and, I think, failed — to figure out what specifically it looks like when the stars so align for artists, and then to go beyond that to ask a question: Is there anything that we can do to help those stars to align?

You know, when absolutely staggering greatness shows up, I don’t think we can pay too much attention to it. We should not just look at it and applaud it, but also try to ask ourselves, in the most serious and intense way possible, What enabled that, and how can we enable something else that’s equally great?

I don’t know the answers to those questions, but I keep thinking about a tossed-off comment in Ian MacDonald’s book. He’s writing about a song that John and Paul wrote together — I don’t remember which one, but it doesn’t matter — and in that song there’s a moment when the standard, the expected, harmonic progression calls for an A major chord — but the Beatles go to A minor instead. Many sophisticated musicologists, MacDonald says, have studied this moment and written with analytical rigor about the harmonic language the Beatles employ at this moment and the different ways one might conceptualize it. But that’s all wrong, MacDonald says.

The key point is this: John and Paul were sitting in a room and each of them had a guitar on his lap. That’s the thing to remember, because every guitar player knows how much easier it is to play an A minor chord than an A major one — and, even more important, how much easier it is to riff on an A minor chord, to introduce hammer-ons and pull-offs that make the song sound better. (This is true when using standard tuning anyway — what I like to call Em7add11 tuning — which the Beatles almost always did.) Almost certainly, MacDonald says, at the moment when the A major chord would’ve been the most obvious thing in the world to play, either John or Paul went to the A minor instead — and lo and behold, it sounded cool. So they kept it.

Handmind at work.

You have to remember that neither of those guys could read music; neither of them wanted to read music. Nor did they have access to modern digital tools for music creation. What did they have? Four things:

guitarsearshandsmusical memoriesAnd those were the tools they needed.

And maybe that’s Step One. If we want to reinvigorate the arts, if we don’t want culture to come to a standstill, maybe we need to start with a radical minimalism. Artists: deprive yourselves of everything except the absolutely essential tools. You can’t stream, you can’t use a DAW, you can’t look anything up online, you don’t have an iPad. You have your sensorium and you have the most basic tools imaginable — a pencil, a lump of clay, a pennywhistle or a ukelele. Go.

October 11, 2023

the wisdom of Sturgeon

It seems that literary fiction is dead — it even has a gravestone. Capitalism? Also dead. Tradition and conservatism apparently achieved a murder-suicide pact, which I guess makes it inevitable that the Judeo-Christian tradition is equally defunct; the fact is pushing up daisies; a consensus of some kind has shuffled off its mortal coil; the metabolic processes of socialism have long been history; liberalism joined the Choir Invisible some time back; even Trumpism has expired and gone to meet its maker. At this point, wouldn’t it be simpler for someone to write to tell us what isn’t dead? Maybe something out there is merely pinin’ for the fjords?

It’s a regrettable rhetorical tic, closely related to others, like the claim that “the internet” — all of it! All trillion pages! — is no fun any more, or the even vaster claim that “culture” — all of it! Everything that humans do together! — has come to a standstill. These vast sweeping hand-wavy universal assertions … is there no end to them? Why can’t they come to a standstill? Why can’t they shuffle off their mortal coil?

You need a generalization you can rely on, and I’ve got one for you. It’s called Sturgeon’s Law: “Ninety percent of everything is crap.” You can do the hand-wavy thing and moan the words “over” and “dead” and “no fun,” or you can follow a better path: sift through the cascade of human productions that come your way to find, and then preserve, the small percentage of it that’s golden.

My name for that pursuit is the Gandalf Option, and I recommend it to you, because (to shift metaphors) it is always better to light a candle than curse the darkness.

back to my books

Pretty much all my life I have been fighting against my instinctive introversion, and now that I have turned 65, I’ve decided to stop fighting. I hope people will see this as the legitimate prerogative of a senior citizen.

When someone – anyone, except those I know very well indeed – asks me to have coffee or a beer, I am filled with a feeling not far from dread. But I have always thought that I shouldn’t give in to the anxiety; instead I have tried to push back. It’s just grabbing a cup of coffee and having a little chat, for heaven’s sake! I tell myself. You’re not being taken in by the Stasi for interrogation. So I make myself say yes, and I make myself go … and while I can manage to be friendly and engaged during the meeting — indeed, more than friendly, way too talkative, out of sheer nervousness — when we’re done I want to go home and sleep for a day or two.

There’s nothing wrong with the people who invite me — indeed, they’re often interesting or even charming, which is the primary reason why I feel I should push back against my instincts. But it’s still taxing to push back. If I were invited to dinner by Bob Dylan or Thomas Pynchon, I’d think, Do I really have to? (But I doubt I can make you believe how serious I am about that.)

There’s a passage in Lynne Sharon Schwartz’s delightful book Ruined By Reading that I think about at least once a week:

Were books the world, or at least a world? How could I “live” when there was so much to be read that ten lives could not be enough? And what is it, anyway, this “living”? Have I ever done it? … Reading is not a disabling affiction. I have done what people do, my life makes a reasonable showing. Can I go back to my books now?

I will continue to attend required meetings, and make plans with my colleagues, and connect with my students during my office hours; and I will with great delight have coffee or beer or dinner with my dearest friends, of whom I am blessed (despite my weird disability) to have a few.

But the main thing is this: I have done what people do, my life makes a reasonable showing. I have a house full of books and music and movies, and I shall go back to them now. If you write to invite me out for coffee or a beer, I will probably send you a link to this post. So please remember: It’s not you, it’s me.

October 9, 2023

vehicles to devices

Here is Ivan Illich, from Energy and Equity (1974), his book written in the midst of a global energy crisis that heightened everyone’s sense of our dependence on fossil fuels for transportation:

The habitual passenger cannot grasp the folly of traffic based overwhelmingly on transport. His inherited perceptions of space and time and of personal pace have been industrially deformed. He has lost the power to conceive of himself outside the passenger role. Addicted to being carried along, he has lost control over the physical, social, and psychic powers that reside in man’s feet. The passenger has come to identify territory with the untouchable landscape through which he is rushed. He has become impotent to establish his domain, mark it with his imprint, and assert his sovereignty over it. He has lost confidence in his power to admit others into his presence and to share space consciously with them. He can no longer face the remote by himself. Left on his own, he feels immobile.

The habitual passenger must adopt a new set of beliefs and expectations if he is to feel secure in the strange world where both liaisons and loneliness are products of conveyance. To “gather” for him means to be brought together by vehicles…. He has lost faith in the political power of the feet and of the tongue.

It’s interesting to reflect that you could replace just a few words here and have a good description of our current moment. For instance, “To ‘gather’ for him means to be brought together by vehicles” would make perfect sense today if you substituted “devices” for “vehicles.” In “He has lost the power to conceive of himself outside the passenger role,” the term “passenger” could be replaced by “user.” A technological regime centered on the automobile has been replaced by one centered on smartphones. This is why teenagers today absolutely must have smartphones but are often indifferent to the possibility of learning to drive.

For Matt Crawford in Why We Drive (2020), to drive an automobile is to assert one’s freedom and responsibility. Crawford’s vision is compelling to many of us in a way it would not have been to Illich, and that is because we live in the Smartphone Era. For those of us who live under technocracy, to contemplate a previously dominant technology feels like sniffing the air of freedom. Which suggests to us, or ought to, that technological development may bring certain kinds of ease and speed but also strongly tends to bring constraint — certain procedures of use are enforced, and variations in such procedures are discouraged or forbidden. We move closer and closer to a world in which all must use the same devices, and in which those devices can be used in one way and one way only.

October 6, 2023

the danger of eulogy

In 1975 Seamus Heaney’s second cousin Colum McCartney — whom it seems he did not know personally — was murdered by members of the Glenanne Gang, Ulster Protestants engaged in a campaign of terror that largely involved killing Catholics at random. McCartney and a friend were returning to their homes in Ulster from a football match in Dublin when they were stopped at a police checkpoint — which turned out to be not a police checkpoint at all. Both were shot in the head.

Soon thereafter, Heaney wrote a poem, “The Strand at Lough Beg,” in memory of McCartney. (It is in his collection Field Work.) In the poem’s final stanza the dead man appears to the poet, appears not where he was killed — that happened “Where you weren’t known and far from what you knew” — but at Lough Beg, a place familiar to the family:

Across that strand of ours the cattle graze

Up to their bellies in an early mist

And now they turn their unbewildered gaze

To where we work our way through squeaking sedge

Drowning in dew. Like a dull blade with its edge

Honed bright, Lough Beg half shines under the haze.

I turn because the sweeping of your feet

Has stopped behind me, to find you on your knees

With blood and roadside muck in your hair and eyes,

Then kneel in front of you in brimming grass

And gather up cold handfuls of the dew

To wash you, cousin. I dab you clean with moss

Fine as the drizzle out of a low cloud.

I lift you under the arms and lay you flat.

With rushes that shoot green again, I plait

Green scapulars to wear over your shroud.

A scapular, worn primarily by monks and priests, offers here an image of prayer and hope, and the poem is prefaced by a quotation from Dante’s Purgatorio. In caring for the body of his dead cousin, then, Heaney is preparing him for his final journey.

Some years later, in Heaney’s harrowing sequence “Station Island” — a sequence shaped more thoroughly by long meditation on Dante than the earlier poem had been — the poet is again visited by his dead cousin, and the visit is not pleasant. In the first poem the poet speaks while the murdered man is silent; in the second the poet must listen to the voice of man he had eulogized. The sequence narrates a pilgrimage to St. Patrick’s Purgatory, a journey involving several encounters with the dead, very like those Dante experiences in his voyage through the Three Realms — except often more uncomfortable.

We have reached the eighth station. Heaney is conversing with “my archaeologist” — Tom Delany, his friend, who died of tuberculosis at age 32 — when suddenly his cousin Colum appears, with a word of accusation:

But he [Delany] had gone when I looked to meet his eyes

and hunkering instead, there in his place

was a bleeding, pale-faced boy, plastered in mud.

‘The red-hot pokers blazed a lovely red

In Jerpoint point the Sunday I was murdered,’

he said quietly. ‘Now do you remember?

You were there with poets when you got the word

and stayed there with them, while your own flesh and blood

was carted to Bellaghy from the Fews.

They showed more agitation at the news

than you did.’

(The Fews is the part of County Armagh where McCartney was murdered; Ballaghy is the village in County Londonderry where Heaney was born and raised and where McCartney was buried.) You did not clean my body and lay me out for burial. You remained in the company of your fellow poets. Heaney pleads for himself, says that the news made him “dumb,” describes the image of Lough Beg just outside Bellaghy that rose unbidden to his mind. (His mind went to the home town they shared, but his body did not.)

Colum is not appeased.

You saw that, and you wrote that — not the fact.

You confused evasion and artistic tact.

The Protestant who shot me through the head

I accuse directly, but indirectly, you

who now atone perhaps upon this bed

For the way you whitewashed ugliness and drew

the lovely blinds of the Purgatorio

and saccharined my death with morning dew.

You confused evasion and artistic tact. You told yourself you heeded your calling by shaping the story artfully, festooning it with imagery; in fact you merely whitewashed the ugliness of my murder. To this charge the poet makes no response — except, of course, the poem itself, which is in fact made of Heaney’s own words, not Colum McCartney’s.

And this is both the problem and the wonder. Philip Larkin once said, in response to a comment about how “negative” his poems are, that “The impulse for producing a poem is never negative; the most negative poem in the world is a very positive thing to have done.” Colum’s accusation against his cousin is just this, that he has done a positive thing — but then, the accusation itself, being couched in masterful verse, is also a positive thing. The poet’s eulogy must be beautiful, even (especially?) when the dead one’s murder was hideous beyond our ability to confront it. It is only in the language of poetry that the poet can acknowledge the limits of the language of poetry.

October 3, 2023

Austen and parents

One of the most notable traits of Jane Austen’s fiction is its gently ironical attitude towards many of its own readers. Consider Emma, for instance. Here is Austen’s description of the key event in Emma Woodhouse’s life: “It darted through her, with the speed of an arrow, that Mr. Knightley must marry no one but herself!” Every reader of the novel (myself included) will tell you that this is a glorious moment. But note: the novel consists of 55 chapters, and this decisive moment occurs in the 47th of them; in the 49th Mr. Knightley proposes to her and is accepted; and so everything that the reader most cares about is wonderfully sorted out. But six whole chapters remain. And why is that? Because Jane Austen is interested in certain matters that her audience is not especially interested in – but (she thinks) ought to be.

Or consider Mansfield Park, in which Austen signals her deviance from popular expectation in a different way. Fanny Price has carried her torch for her cousin Edmund helplessly and hopelessly for several hundred pages – this is the longest of Austen’s novels – and then, a mere seven paragraphs from the end, we get this:

I purposely abstain from dates on this occasion, that every one may be at liberty to fix their own, aware that the cure of unconquerable passions, and the transfer of unchanging attachments, must vary much as to time in different people. I only entreat everybody to believe that exactly at the time when it was quite natural that it should be so, and not a week earlier, Edmund did cease to care about Miss Crawford, and became as anxious to marry Fanny as Fanny herself could desire.

As much as to say: “Oh, you still want Edmund and Fanny to marry, do you? Well, if you insist, be it so – but I really can’t be bothered to narrate their courtship.”

What Austen cares about – what she devotes her extraordinary intellectual energies to – is the moral and intellectual formation of young women. Austen perceives her society to be one in which people have great expectations for young women, and place exceptionally great demands upon them, but does almost nothing to prepare them to meet either the expectations or the demands.

In Mansfield Park Sir Thomas Bertram, the head of the family with whom the story is concerned, is a good man, an admirable man in many respects, but is regularly described as “cold” and “severe”; his wife, Lady Bertram, is called “indolent”; and Lady Bertram’s sister, the Mrs. Norris, who has the greatest influence over their daughters precisely because the parents are either cold or indolent, is “indulgent.” In Emma, Emma’s mother is dead and her father a hypochondriac whole manifold sensitivities make him, in his own way, as indolent as Lady Bertram.

Pride and Prejudice is more conventionally structured around the marriage of its heroine – which is perhaps why Austen thought that “The work is rather too light, bright and sparkling: it wants shade” – but even there one might argue that Elizabeth Bennett suffers in several ways from the moral idiocy of her mother and the ironic detachment of her father. But these, I submit, are not the typical dispositional errors of parents: the typical ones are laid out in Mansfield Park: severity, indolence, and indulgence.

Fanny Price and Emma Woodhouse from their childhood have older men in their lives who provide them guidance, counsel, and (in the end, as we have seen) matrimony. But along the way to that conventional Happy Ending they suffer many vicissitudes, painful episodes that, Austen suggests, they might not have suffered if their parents had provided them with consistent and loving guidance. When parents are badly formed, Auden consistently indicates, their children will be badly formed as well; and while poor moral formation is unfortunate for any children, in that particular society the girls consistently paid a bigger price. And not many girls are fortunate enough to have the regular attention of a Mr. Knightley or cousin Edmund.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers