Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 199

May 24, 2020

serious questions for churches

The question I would ask churches that are re-opening without masks or distancing, but with lots of congregational singing, is: How do you think infectious disease works, exactly? How do you think COVID–19 is transmitted? What’s the theory you’re operating on?

I’m going to assume that the leaders of such churches believe that infectious diseases exist, that there are illnesses that pass from person to person via contact or proximity. I am also going to assume that they believe that COVID–19 is one of these infectious diseases.

I wonder how many such leaders are aware that health organizations all over the world — not just American organizations run by Trump-hating libtards — generally agree about how COVID–19 is transmitted? See for instance this poster from the Japanese Ministry of Health:

And perhaps they have read about the dramatic and terrible rate of illness among the members of this community choir?

Given all the information available, I’m wondering what they actually believe — not just about what their rights are, or about what they should be allowed to do — but rather about this disease. Some of the more likely options:

It’s all fake news, even that thing from Japan. There’s nothing to worry about, COVID–19 is no worse than the flu. All those reports of death? FAKE NEWS. Massive conspiracy concocted by global elites.

Some of it is true, but the dangers are dramatically exaggerated by the global elites, we’ll probably be fine. Also, masks don’t work.

It was very dangerous, but it’s all over now — the President wouldn’t be telling us to open up if it weren’t safe to do so.

It’s still dangerous, but we’re putting our trust in God, counting on Him to protect us.

It doesn’t matter whether it’s dangerous or not. If we perish, we perish. We may all get sick, we may all even die, but we’re not supposed to count the cost of following the Lord.

My guess is that the churches choosing to open — when they can; some that want to are now forbidden to do so — are using any and all of the above options as needed. Theirs is a castle with many mottes and many baileys. I don’t believe that churches re-opening for business-as-usual, or seeking to re-open for business-as-usual, have assessed the evidence and made prudential judgments in light of that evidence. They have decided to act on what they want to do, and then will employ whatever ex post facto justifications seem best in the moment, according to the arguments marshaled against them.

So we should expect to see any of the five defenses listed above, and perhaps others I have neglected, deployed from once moment to the next, even though those defenses aren’t necessarily consistent with one another. The answer to my initial question, then, is that the leaders and members of such churches will believe whatever at a given moment seems useful to justify acting on their desires. ’Cause in much of America today, that’s how we roll.

May 21, 2020

thread

Nothing is stupider than using Twitter to write anything longer than, you know, a tweet. This we know.

It’s a terrible experience first for the writer and then for the reader. Thread Reader is meant to make things less miserable for readers, and to some degree it accomplishes that, but whenever someone sends me a thread — I would never choose to look at one — you know what I inevitably think? Lordy, this is badly written. See, Thread Reader can’t do anything to reverse the damage the 280-character limit inflicts on a person’s writing: such writing is invariably choppy, imprecise, abstract, syntactically naïve or incompetent, lacking in appropriate transitions — a total mess in every respect. (Some of this happens because the writers get distracted by comments that start coming in before they’ve finished the thread, but an undistracted threader is still a poor writer.)

When you write a Twitter thread, what you are telling me is that you don’t care about your own ideas enough to articulate and display them in a proper venue. And if you don’t have respect for your own ideas, you certainly can’t expect me to.

You don’t have to create a blog of your own to post something to the web. You can use a free service like Rentry — I used to recommend also txt.fyi but I think it’s dead. You can even do what the celebs do and write something in Apple Notes, screenshot it, and tweet it as an image. There are a hundred ways to post longer-than–280-characters writing to Twitter, and when you write threads you are choosing the very worst one.

May 20, 2020

Wittgenzen

In a new and extra-special edition of his newsletter, Robin Sloan writes about why he likes texts that have “a modular structure, an accelerated pace — a bit of TV’s DNA grafted into the capacious form of the book.” And he thinks about how this kind of writing, as exemplified by Georges Simenon’s brief, arrowing Maigret novels, court the world of pulp:

And while the utter disposability of a lot of pulp (culturally as well as physically) isn’t appealing, some of its other characteristics are VERY appealing. Speed! Unpretentiousness. Accessibility. And seriality, of course: the feeling of discovering the first installment in a series and, if you like it, zooming forward, absolutely devouring it, until you join the mass of readers who are caught up, waiting for the next release.

And then he says, “Okay, so, for many years, I’ve thought, wouldn’t it be wonderful to produce something with that shape? — an ongoing series of relatively small pieces published at a steady clip, gathered up later into something substantial.”

I find this thought both interesting and appealing, and I want to expand it. because Robin is also helping to write a video game, creating his own video game, sending little stories in the mail … and I wonder whether the idea of many “small pieces published at a steady clip, gathered up later into something substantial” might encompass not just pieces that are published in the familiar genres of fiction but might also extend to other genres and even other media altogether. You could end up with something like a multifaceted jewel, a body of work that has a kind of thematic integrity, but an integrity that might be discernible in full only by the person who made it.

But maybe to some considerable degree by the most sympathetic and attentive of readers/viewers/listeners/ players. Owen Barfield once wrote of his friend C. S. Lewis, “There was something in the whole quality and structure of his thinking, something for which the best label I can find is ‘presence of mind.’ If I were asked to expand on that, I could say only that somehow what he thought about everything was secretly present in what he thought about anything.”

A consummation devoutly to be wished, as I think about my own career anyway.

Bruce Sterling has just announced that he’s wrapping up his 17-year run on his blog. I’m going to quote at length:

I keep a lot of paper notebooks in my writerly practice. I’m not a diarist, but I’ve been known to write long screeds for an audience of one, meaning myself. That unpaid, unseen writing work has been some critically important writing for me — although I commonly destroy it. You don’t have creative power over words unless you can delete them.

It’s the writerly act of organizing and assembling inchoate thought that seems to helps me. That’s what I did with this blog; if I blogged something for “Beyond the Beyond,” then I had tightened it, I had brightened it. I had summarized it in some medium outside my own head. Posting on the blog was a form of psychic relief, a stream of consciousness that had moved from my eyes to my fingertips; by blogging, I removed things from the fog of vague interest and I oriented them toward possible creative use….

A blog evaporates through bit-rot. Yet even creative work which is abandoned and seen by no one is often useful exercise. One explores, one adventures by finding “new ground” that often just isn’t worth it; it’s arid and lunar ground, there’s nothing to farm, but unless you venture beyond and explore, you will never know that. Often, it’s the determined act of writing it down that allows one to realize the true sterility of a silly idea; that’s how the failure gets registered in memory; “oh yes, I tried that, there’s nothing there.”

Or: maybe there is nothing there yet. Or: it may be ‘nothing’ for me in particular, but great for you. “Nothing” comes in many different flavors.

What I find interesting is how Sterling thinks of the whole set of writing venues, from private notebook to blog to published fiction and nonfiction, as a single endeavor, each element of which is necessary but not in predictable ways. And what those elements are necessary to is the development of his own thinking.

I think what Robin Sloan and Bruce Sterling in their posts are pointing me towards, whether they mean to or not, is a different way of looking at these matters. Maybe the really important thing is not whether an idea gets published, or the genre or medium in which it makes its way into the world, but the integrity of my Gedankenwelt, my thoughtworld. A kind of Wittgensteinian reorientation in which publication may happen, but whether it does or not is effectively external to the real project.

I’d like to get to that posture of serenity and unconcern, but instead I spend a lot of time worrying over the relations among the various kinds of writing I do. And it occurs to me that the major impediment to my achieving what I have just decided to call Wittgenzen is the publishing industry.

Now, to be sure, and without any doubt, the publishing industry has been very good to me. I am enormously grateful to my agent and my editors for bringing my voice before the public. But one thing the publishing industry, for understandable reasons, doesn’t like is to pay for something that has been made public, even in part, somewhere else. The more I write about something on this blog, the lower the chance that I will be able to sell a more-fully-developed version of it to a publisher.

And yet blogging, for reasons Bruce Sterling has laid out, is good for thinking, for my thinking anyway. To borrow a metaphor from my friend Sara Hendren, who borrow it from engineering, blogging is a kind of sketch modeling: something more ordered and structured that notebook jottings, and less fixed and complete than a published book. Moreover, blogging is formally networked in ways that neither notebooks or books are: each post is linked not only to the online writings, or images, or films that it interacts with, but also via tags to other similar posts. Properly executed, a blog can approximate Walter Benjamin’s Arcades project, for reasons suggested by Eli Friedlander in this essay on Benjamin. Or, to put it another way, a blog is a Wittgenzen garden.

So here’s my situation: the more I write at this blog, the less opportunity I will have to publish my work in book form; but also, the more I write on this blog, the better I will think. I still believe in lateral thinking with seasoned technology; I am still trying to put myself in a position where I don’t know where I’m going. But it’s not only easier, it somehow feels more responsible to take advantage of my publishing opportunities, which so many people would love to have. (Also: cash money.)

As those posts I just linked to will show, I’ve been going around in this circle for years now. But one of these days I’m gonna figure it out. One of these days I’m gonna take the plunge into the who-knows-what of Wittgenzen. These posts are here to give me courage and wisdom for that day.

May 16, 2020

deep literacy?

The problem here is the lack of evidence that “deep literacy” really is in decline. Decline from what height? Starting when? Also:

The rise of deep literacy in enough people in early modernity — mightily aided, of course, by Gutenberg’s invention of movable type — was a precondition of Protestantism’s firm establishment and rapid growth, and its establishment was in turn a major accelerator of deep literacy in the societies in which it became the principal faith community, in large part because Protestants ordained compulsory schooling for all children. The Reformation found a very powerful engine in the establishment of these schools: Wherever Protestant beliefs spread, state-mandated education soon followed, each reinforcing the other.

“Protestants ordained compulsory schooling for all children” — all of them? Everywhere? I don’t think so. When and where did this happen? Perhaps Maryanne Wolf provides evidence for these claims in her book, but if so citations of some kind would have been useful. And in any case Wolf is not a historian. Here’s a widely-cited article from 1984 that asks about the relationship between literacy and the Reformation in Germany. The authors conclude that the early Lutherans weren’t especially interested in promoting general literacy — they devoted themselves to promoting catechesis in schools, and this was done orally — and relatively little progress was made in promoting general literacy until the Pietists in the eighteenth century became influential. And even then the achievements were modest:

Besides reorganizing and revitalizing school systems still suffering from the effects of the Thirty Years War, the eighteenth-century ordinances set targets gradually achieved over time. Indicative of the type of incremental progress that was made are some statistics from East Prussia, one of the poorest rural areas in Germany. The percentage of peasants who could sign their names rose from 10 per cent in 1750, to 25 per cent in 1765, to 40 per cent in 1800. Another sign of increasing literacy was the exponential growth in the book trade in the last half of the eighteenth century as the number of titles for sale at the Leipzig book market, the largest in Germany, increased by over 50 per cent between 1740 and 1770 and more than doubled between 1770 and 1800. To be sure, the increase in literacy and reading in the late eighteenth century was still spotty and varied widely in depth and intensity from place to place. Best estimates of school attendance in the second half of the eighteenth century range from one-third to one-half of German school-age children.

How much deep literacy could there be in an environment in which basic literacy was by no means complete — in some areas not even widespread? That’s just in Germany, of course; comparative study needs to be done to make a more general case.

You can’t effectively make an argument like this without being able to answer some questions:

How, specifically, do we distinguish deep literacy from more basic kinds of literacy?

Where and when have rates of basic literacy been highest?

What data do we have, for any of those places and times, to indicate the proportion of people achieving deep literacy (measured in relation both to basically-literate persons and to the whole population)?

Just to start. And I would ask a deeper and harder-to-answer question: For the overall health of a society, is it the number of people who achieve deep literacy that matters? Or is it the social and political influence of the deeply literate?

May 15, 2020

mail time

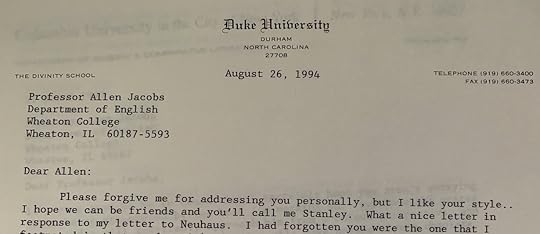

When I was writing my previous post I dug through my ancient folder of correspondence — which documents the pre-Cambrian era during which people wrote letters to one another — to find my exchanges with Father Neuhaus, and in so digging I found a couple of other things of interest.

On of my first essays linked some of Auden’s work to the thought of Alasdair MacIntyre, and I decided to send an offprint of the article to that philosophical hero of mine, with my compliments. I was, as you might expect, delighted with this reply:

A few years later, I wrote for First Things an essay that was rather critical of Stanley Hauerwas, so I didn’t send that one to its subject. But Stanley read it and soon thereafter I got this in the mail:

“I like your style.” What a guy. Even if he spelled my name wrong.

what to say about First Things?

People keep writing to me about the Reno Incident, usually wanting to know what I think it says about First Things as a magazine, and aside from saying, on Twitter, that I think this post by Rod Dreher puts the whole business in the proper context, I’m not sure what to add. But I’m gonna give it a try.

My history with First Things is long and rather complicated. I’ve written about it before, in bits and pieces, but let me sum up here. When the magazine was just a few months old, I found a copy when, on a visit to the University of Chicago, I ducked into 57th Street Books to browse the periodical shelves. There was nothing like it at the time, at least that I knew of, and I fell in love right away. A magazine that took both religion and ideas seriously! First I subscribed, and then I submitted two shortish essays to the editors. Jim Neuchterlein wrote back accepting one of them — strangely enough, it was about Talking Heads — and a beautiful friendship was born. Over the next two decades I appeared in the magazine approximately fifty times: feature essays, shorter opinion pieces, book reviews.

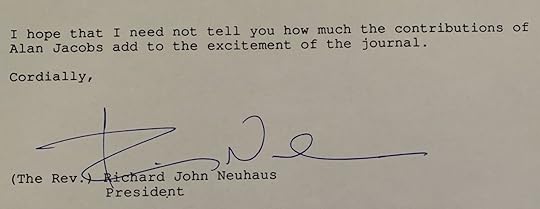

I did sometimes feel, after Richard John Neuhaus became a Roman Catholic and then a priest — having before that been a Lutheran minister —, that the evangelical wing of small-o orthodox Christendom was occasionally slighted in the pages of the journal, and once I wrote to Father Neuhaus to tell him so. After a few days he replied:

Well, I thought, that’s generous. And then a bit of gentle pushback, followed by further reassurances:

And, as if he hadn’t completely won me over, this concluding flourish:

He could charm, that man.

I loved writing for First Things, and if I had had my way, I’d have spent the rest of my career writing for that magazine and for John Wilson at the late and so-deeply-lamented Books & Culture. (John’s greatest gift to me, as an editor, was to connect me with books that I could interact with creatively; Jim Neuchterlein’s greatest gift was to teach me about the control of tone, something I really struggled with early in my career.) But I did not get my way. B&C was shut down, and even before that things started getting weird at FT. I have always liked Jody Bottum, and admire him as a writer, but as an editor he was difficult to work with, and when Jim retired and Jody took over, he simply rejected everything I sent him. I had had no rejections from FT in twenty years, and now I could get no acceptances! It was never clear to me exactly what was going on — especially since Jody kept telling me what a wonderful writer I was — but eventually I gave up and started looking elsewhere. Which is how I ended up writing for places like the Atlantic and Harper’s and the New Yorker — because I wasn’t good enough for First Things. Or was no longer “a fit,” anyway. It was, and still is, hard for me to know how much I had changed and how much they had.

Not, for a long time, being willing to give up altogether, I managed to get a handful of things in the magazine, but it was obvious that my relationship with it was never going to be the same. And then things started getting more generally strange. A kind of … I’m not quite sure what the word is, but I think I want to say a pugilistic culture began to dominate the magazine. When I submitted a piece to an editor, another editor wrote me an angry email demanding to know why I hadn’t submitted it to him; whenever I disagreed with Rusty Reno about something, he would, with such regularity that I felt it had to be intentional, accuse me of having said things I never said; once, when I made a comment on Twitter about the importance of Christians who share Nicene orthodoxy working together, another editor quickly informed me that I’m not a Nicene Christian. (Presumably because, since I’m not a Roman Catholic, I don’t really believe in “the holy Catholic church.”)

I suspect all these folks would tell a different story than the one I’m telling, so take all this as one person’s point of view, but more and more when I looked at First Things I found myself thinking: What the hell is going on here? Sometimes the whole magazine seemed to be about picking fights, and often enough what struck me as wholly unnecessary and counterproductive fights. (Exhibit A: the Mortara kerfuffle.) So I stopped submitting, and then I stopped subscribing, and then for the most part I stopped reading. This isn’t a matter of principle for me: Whenever someone recommends a piece from the FT magazine or website to me, I read it, and if I like it I say so (usually on Twitter). But effectively there is no overlap any more between my mental world and that of First Things. I regret that.

Rod Dreher is correct to say, in a follow-up to the post I linked to at the top of this piece, that no other magazine of religion and public life, or religion and intellectual life, has the reach of First Things. But I think the decision by the editors of FT to occupy the rather … distinctive position in the intellectual landscape that they’ve dug into for the past few years has left room for a thousand flowers to bloom in the places that FT is no longer interested in cultivating. I have gotten more and more involved with Comment; they’re publishing some outstanding work at Plough Quarterly; even an endeavor like The Point, not specifically religious at all, makes room for religious voices: My recent post there on Terrence Malick’s A Hidden Life would surely have been an FT essay in an earlier dispensation of the magazine. All is not lost. But I fear that First Things — at least in relation to the mission it pursued so enthusiastically for a quarter-century — is lost.

May 14, 2020

QAnon: costs and benefits

In Toledo, I asked [a woman named Lorrie] Shock if she had any theories about Q’s identity. She answered immediately: “I think it’s Trump.” I asked if she thinks Trump even knows how to use 4chan. The message board is notoriously confusing for the uninitiated, nothing like Facebook and other social platforms designed to make it easy to publish quickly and often. “I think he knows way more than what we think,” she said. But she also wanted me to know that her obsession with Q wasn’t about Trump. This had been something she was reluctant to speak about at first. Now, she said, “I feel God led me to Q. I really feel like God pushed me in this direction. I feel like if it was deceitful, in my spirit, God would be telling me, ‘Enough’s enough.’ But I don’t feel that. I pray about it. I’ve said, ‘Father, should I be wasting my time on this?’ … And I don’t feel that feeling of I should stop.”

Why do people believe such things? After all, there is no evidence that anything Q says is true; there is no reason to believe in Q’s Gospel. Or even to believe that Q is a single person. Or, if Q is a single person, that he or she isn’t doing it for the lulz.

The answer, I think, is pretty straightforward: Believing in Q has many benefits but very low marginal costs. Believing in Q gives people a sense of having tapped into the hidden meaning of things, an explanation for their low social status, and a strong network of like-minded people. WWG1WGA, as the QAnon mantra goes: “Where we go one, we go all.” These are significant benefits!

And those marginal costs? I suppose time spent on matters Q is time one can’t spend on Netflix; and if educated people mock and laugh at the followers of Q, well, weren’t they already mocking and laughing at people like Lorrie Shock? How does believing in Q change anything in that respect? Nor does Q-following affect the ability of those followers to do their jobs or raise their children.

Again: significant benefits, low marginal costs. Looked at from that point of view, belief in Q demonstrates a kind of rationality.

LaFrance writes, near the end of her excellent report,

The Seventh-day Adventists and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are thriving religious movements indigenous to America. Do not be surprised if QAnon becomes another. It already has more adherents by far than either of those two denominations had in the first decades of their existence. People are expressing their faith through devoted study of Q drops as installments of a foundational text, through the development of Q-worshipping groups, and through sweeping expressions of gratitude for what Q has brought to their lives. Does it matter that we do not know who Q is? The divine is always a mystery. Does it matter that basic aspects of Q’s teachings cannot be confirmed? The basic tenets of Christianity cannot be confirmed. Among the people of QAnon, faith remains absolute. True believers describe a feeling of rebirth, an irreversible arousal to existential knowledge. They are certain that a Great Awakening is coming. They’ll wait as long as they must for deliverance.

In order to evaluate this view of the matter, I think we need to press hard on the word “adherents.” People who spend a lot of time chasing down Q on the internet don’t really qualify. Even the occasional IRL meetup won’t do it. A movement gains genuine adherents when the costs of belonging to it — financial, social, intellectual, legal — reach a kind of critical mass of pain. The blood of the martyrs is the seed of every church.

May 13, 2020

how hard

I know that one of the most frustrating things you can say to a software developer is “It can’t be that hard.” Because unless you actually are a developer you really don’t know how hard something can be. That said …

I was very excited about the new release of iA Writer because it promises something that I’ve been hoping for for years: the ability to post directly, from its iOS app, to a self-hosted WordPress site. All that the app has previously offered is a super-kludgy way to, basically, copy what you’ve written and paste it into a text field in the WordPress app. (In which case you might as well, you know, write in the WordPress app.) So I downloaded the new version, fired it up … and found out that it requires me to install a WordPress plugin before it can publish. But the required plugin, it seems, does not work with my hosting provider — or something: for whatever reason, it doesn’t work.

Here’s the thing, though: Byword is not nearly as elegant or capable a text editor as iA Writer, but it has featured the ability to post to any WordPress-based site, directly and frictionlessly, for years. No kludges, no plugins; just write and publish. So, I just can’t help saying to the people at iA Writer: It can’t be that hard, can it?

(Post written in, and published from, Byword.)

free as in more coffee

I use the Freedom app to keep me off Twitter for 22 hours a day. I get an hour in the morning and an hour in the evening to check what’s happening.

Freedom isn’t perfect: especially on iOS it sometimes fails to kick in until I open the app. (Today mid-morning I reflexively checked Tweetbot and chatted with folks for a few minutes before I realized that I shouldn’t be able to do that. I quickly opened Freedom and then found my way blocked. Relief!) But overall it’s great.

I tend to think of Freedom in theological terms, as a technological instrument to produce instant infused righteousness. After all, did not Augustine say — see the last paragraph of the City of God — that the blessed are truly free because they are unable to sin? And does not Freedom prevent me from tweet-sinning? (I see that I need to add prevenient grace to my theology-of-social-media vocabulary.)

Anyway, here’s the best thing about Freedom: It allows whole cycles of tweet-rage to pass me right by. Sometimes I wake up in the morning and check Twitter and see some outrageous thing that some dunce tweeted the previous day or evening, something that I might be very tempted to respond to — but by the time I see it that person has already been raked over the coals so thoroughly that he’s already dead. It’s great. Thanks, friends, for doing the Lord’s work for me so I can have another peaceful cup of coffee.

May 12, 2020

another case for the humanities

Samuel Johnson was impressed by the intelligent and ambitious structure of learning that Milton laid out in “Of Education,” but, as he explains in his Life of Milton, he thought the scheme gave too much attention to what Milton would have called “natural philosophy” and what we call “science.”

But the truth is that the knowledge of external nature, and the sciences which that knowledge requires or includes, are not the great or the frequent business of the human mind. Whether we provide for action or conversation, whether we wish to be useful or pleasing, the first requisite is the religious and moral knowledge of right and wrong; the next is an acquaintance with the history of mankind, and with those examples which may be said to embody truth and prove by events the reasonableness of opinions. Prudence and Justice are virtues and excellences of all times and of all places; we are perpetually moralists, but we are geometricians only by chance.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers