Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 198

May 28, 2020

my expert opinion

Americans have never more desperately needed reliable knowledge than we do now; also, Americans have never been less inclined to trust experts, who are by definition the people supposed to possess the reliable knowledge. There are many reasons why we have landed ourselves in this frustratingly paradoxical situation, and there’s no obvious way out of it. But I want to suggest that there’s one small thing that journalists can do to help: Stop using the word “experts.”

Of course, expertise is a real thing! — though perhaps not quite as commonplace a thing as is widely believed. In most of life’s situations we understand the value of expertise: few of us try to repair our own computers, and none of us decides to remove his own spleen. But occasionally we draw a line.

Some are inclined to draw that line in strange places — say, believing that the moon landing was faked, or that the world is ruled by lizard people. But the really common dissents seem to come in matters of health: you might not know any moon-landing skeptics or lizard-people True Believers, but you surely have an anti-vaxxer cousin, or an aunt whose belief in the healing power of essential oils persists in defiance of her doctor’s counsel. And if you’re going to try to persuade those dissenters from standard opinion to change their minds, almost the worst thing you can do it appeal to “experts.”

There are three reasons for this. The first is that many people with genuine expertise in a given field have a difficult time staying in their lane. I have long thought that the perfect example of this is the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The question of whether we are close to nuclear war is a political question, not a scientific one; an “atomic scientist” has no reasonable claim to knowing any more about it than you do, at least, not by virtue of being an atomic scientist. (Factoring climate change into the Doomsday scenario doesn’t help matters much, because atomic scientists aren’t climate scientists any more than they are psychiatrists or nutritionists.)

A second reason that invocations of expertise often fail is simply that people with equivalent expertise in the same field often disagree. This leads to the phenomenon, familiar to anyone who has ever flipped from one cable news station to another, of Dueling Experts.

The third, and most important, reason why appeals to expertise are futile is that the term “expert” functions as a kind of class marker. An expert is One Who Knows, a member of the noocracy or epistocracy — and you are not. “Experts say” is a phrase that often carries a strong implication: “So shut up and heed your betters.” This is not the sort of message that Americans like, even when maybe they ought to.

My suggestion to journalists, then, is simple: Never use the word “expert.” If you are tempted to say “We talked to an expert,” say instead that you talked to an immunologist, or an epidemiologist — and then take a moment to explain what an immunologist or epidemiologist actually is. Tell us that you talked to someone who has spent twenty years studying the ways that diseases are transmitted, especially from one person to another. Yes, that takes longer than saying “expert,” but it’s worth it. To describe the person you’re interviewing or quoting in that more detailed way tells a little story, a story not about someone standing on a pedestal labeled “EXPERT,” but rather a person who is continually working to learn more. A person who has thought hard, and tested her ideas, and worked with colleagues who care about the same things. A person whom we should listen to not because she belongs to a certain class that’s higher than ours, but rather because she‘s dedicated to gaining knowledge — and knowledge directly relevant to the questions we’re all asking right now.

It should be obvious that this discipline will also ensure that journalists rely on people with the appropriate knowledge. When you’re scrambling to find someone to interview or cite and can only find someone whose field is but tangentially related to the question at hand, he word “expert” can neatly obscure your problem.

All this takes more time and effort. But the word “expert” has been poisoned now for millions of people, and not always for bad reasons. I know that in journalism time is often short and word-count limited, but journalists have a responsibility to educate as well as inform their public, and this is a way to do that better. After all, you want to be an expert communicator, don’t you?

May 27, 2020

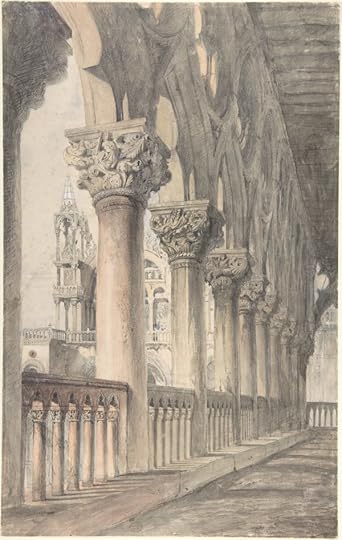

St. Mark’s

I love these pencil sketches by Ruskin that he later filled in with watercolor or colored pencil

I love these pencil sketches by Ruskin that he later filled in with watercolor or colored pencil

May 26, 2020

Palazzo Dario, Venice

“Titanic insanity”

And among such false means largeness of scale in the dwelling-house was of course one of the easiest and most direct. All persons, however senseless or dull, could appreciate size: it required some exertion of intelligence to enter into the spirit of the quaint carving of the Gothic times, but none to perceive that one heap of stones was higher than another. And therefore, while in the execution and manner of work the Renaissance builders zealously vindicated for themselves the attribute of cold and superior learning, they appealed for such approbation as they needed from the multitude, to the lowest possible standard of taste; and while the older workman lavished his labor on the minute niche and narrow casement, on the doorways no higher than the head, and the contracted angles of the turreted chamber, the Renaissance builder spared such cost and toil in his detail, that he might spend it in bringing larger stones from a distance; and restricted himself to rustication and five orders, that he might load the ground with colossal piers, and raise an ambitious barrenness of architecture, as inanimate as it was gigantic, above the feasts and follies of the powerful or the rich.

John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice

May 25, 2020

“I hated it with, like, a powerful hate”

on misunderstanding critical theory

Recently there’s been a lot of talk among conservatives about “critical theory,” and it’s been puzzling me. So finally I looked into the matter and think there’s some confusion that needs to be sorted out.

The person who has been leading the charge in the identification and denunciation is James Lindsay, of the grievance studies hoax fame, and he has helped to generate a whole discourse about critical theory, much of which you can find at Areo Magazine. If you look at the essays there, you’ll see some that identify critical theory quite closely with the works of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer — the leading members of the so-called Frankfurt School — but then others, who clearly think that they’re talking about the same phenomenon, lump Adorno and Horkheimer together with thinkers who differ from them quite dramatically, like Heidegger and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Lindsay himself uses the term “critical theory” in extraordinarily flexible ways, sometimes quite narrowly and sometimes expansively. It can be hard to tell in any given sentence of his what the intended range of reference is.

To someone like me who has been studying and teaching and writing about this stuff for thirty years, the whole discourse is pretty disorienting because, frankly, so much of it is just wrong. It’s like listening to people talking about a “Harvard school” of political theory that features John Rawls and Robert Nozick; or a “California school” of governance to which both Ronald Reagan and Gavin Newsom belong.

However, the folks who write for Areo didn’t arrive at this confusion all by themselves. It’s endemic to the humanistic disciplines, in which “theory” can be used in many ways, some of which involves the acts of social and cultural and literary “criticism” — which of course is also an ambiguous word, since it can denote close attentiveness or a negative view of something. I am an Auden critic, but that doesn’t mean I am critical of Auden. All these things get mixed up together, and have done so for a long time. Decades ago, when I started teaching a class on these themes at Wheaton College, the class was called “Critical Theory,” but what it was really about was “Literary Theory.” I asked for the name of the course to be changed because I thought that the phrase “critical theory” should be reserved for the Frankfurt School tradition, but several of my colleagues were puzzled by this request, thinking that “critical theory” and “literary theory” were functionally synonymous terms. I seem to recall one saying that the existing description was better because the class was really about literary criticism rather than literature as such. Theory of criticism = critical theory.

So no wonder Lindsay and his colleagues get confused. But let’s try to straighten things out a bit.

In the broadest sense, literary theory and cultural theory are academic disciplines based on the conviction that the ways we think about our humanistic subjects are not self-evidently correct and require investigation, reflection, and in some cases correction. This impulse arises in part from the experience of teaching, in which we discover that our students tend to do things with literary and historical texts — for instance, decide whether they like a book or a historical account on the basis of whether or not they “relate” to its most prominent characters — that we would prefer them not to do. But also, there was some 80 years ago a fight in America (it happened earlier and rather differently in the U.K.) to convince academic administrations that the study of literature was not simply impressionistic, like some higher book club, and writing about literature was not merely belletristic. Rather, we’re doing serious, disciplined academic work over here! And to prove it, and then to teach our students, we’re developing a theory.

All this ferment is of course related to science envy: the need to reckon with the fear that science has a method and humanistic study does not. A theory at least approximates a method, and there arose some considerable agitá about whether there’s anything scientific (truly methodical) about what literary critics do. The most influential literary critic of the middle of the twentieth century, Northrop Frye, said in his landmark book Anatomy of Criticism that literature is not a science but literary criticism is, or should be. Not everyone agreed, but everyone did seem to think that literary criticism needed to give an account of itself, needed to specify and enumerate its procedures. In a famous essay, Steven Knapp and Walter Benn Michaels defined theory as “the attempt to govern interpretations of particular texts by appealing to an account of interpretation in general.” They didn’t think this could actually work, which is why they called their essay “Against Theory,” but even people who agreed that it didn’t work, like Stanley Fish, still acknowledged the necessity of “theory talk.”

So this theory talk — which started in Europe well before the likes of Northrop Frye came around — spawned a proliferation of schools, and not just in literary study but also in other humanistic disciplines, among which there was a great deal of overlap in terminology and approach. And, in relation to the arguments that James Lindsay makes, almost none of this was closely related to the Frankfurt School’s “critical theory.” Adorno and Horkheimer and friends had some influence, to be sure, but not not nearly as much as, say, the structuralism that made its way into literary study via Claude Levi-Strauss’s anthropology, or the various psychological theories that stemmed from the work of Freud and Jung. Then came post-structuralism, deconstruction, feminism, gender theory, body theory, postcolonial theory, ecocriticism — all of which were critical and theoretical but usually had only minimal overlap with the concerns of the Frankfurt School. (The figure that I think most generative for Critical Race Theory, Franz Fanon, was in no way connected to the Frankfurt School’s critical theory, as far as I can tell. All of his guiding lights were French.) Certainly each movement operated according to their own internal logic.

But there is among all of these a family resemblance, just not one in which the Frankfurt School has any kind of initiating role. All of these movements assume that (a) most of the time we don’t really know what we’re doing and (b) we’d rather not know, because if we did know why we do the things we do we might not like it. The French philosopher Paul Ricoeur famously wrote that all of these recent movements descend from the three great nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century “masters of suspicion”: Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud, the “destroyers” of the common illusions from which we derive so much of our placid self-satisfaction. So if you’re going to blame anyone for the corrosive skepticism of Critical Race Theory and the like, you’ll need to start well before the Frankfurt School.

And one more thing: as Ricoeur knew perfectly well, there were other great destroyers of illusions in the nineteenth century, perhaps chief among them Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky — but those two did it in the name of the Christian faith. Because no less than Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud, Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky knew that the human heart is deceitful above all things, and added that it is deceitful in ways that we cannot through our own efforts fix. Perhaps the chief problem with the masters of suspicion, and their heirs, is not that they are too suspicious but that they are not suspicious enough. Especially about themselves.

fifteen years ago

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers

John Ruskin

John Ruskin

John Ruskin

John Ruskin

By Giacomo Boni;

By Giacomo Boni;  This thing is going crazy

This thing is going crazy

Teri took this picture of Wes and me on our visit

Teri took this picture of Wes and me on our visit  This is where we were headed (photo by me)

This is where we were headed (photo by me)