Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 16

December 20, 2024

the work itself

Robin Sloan recommends a post by Kyle Chayka on “the new rules of media.” But my immediate question, upon reading it, is: “Rules” for what or for whom? And the answer, when you think for a moment, is clear: Rules for people who want to cut a certain figure in the world, people who want to be independent media creators — people, in short, who want to be influencers. People who don’t really care what they’re influencing others to do or to be as long as they themselves are the ones doing the influencing, and (of course) getting paid for it.

Perhaps because I’ve been reading and thinking about Dorothy Sayers, for whom the nature and value of work is the essential obsession, I have come to be hyper-aware of the chasm that separates (a) those who desire a certain visible and acknowledged place in the world and (b) those whose desire is to do good work. There’s not one word in Chayka’s post on the quality of what you do; every word is, instead, about commanding an audience. It’s a post full of good advice (probably?) for people who simply and uncomplicatedly crave attention.

(Some of those people crave attention because attention leads to money, but I have a suspicion that more of them are interested in money only as a substantial token of attention. Almost everyone seeking a media career could make more dough in jobs that no one notices.)

Sayers originally expresses her convictions about the intrinsic value of good work in her detective novels, through the character of Harriet Vane. But the first writing of hers wholly devoted to this question is the play The Zeal of Thy House, which concerns an architect — a real one, William of Sens — who has to learn through great suffering that he does not matter as much as his work: the choir of Canterbury Cathedral.

(Ginormous version of that photo here.)

I would submit that it’s not even possible nowadays to think of a media career in terms of the work itself, the value of what one does. And maybe that’s what Robin Sloan is suggesting when, after citing Chayka, he continues:

Sometimes I think that, even amidst all these ruptures and renovations, the biggest divide in media exists simply between those who finish things, and those who don’t. The divide exists also, therefore, between the platforms and institutions that support the finishing of things, and those that don’t.

Finishing only means: the work remains after you relent, as you must, somehow, eventually. When you step off the treadmill. When you rest.

Finishing only means: the work is whole, comprehensible, enjoyable. Its invitation is persistent; permanent. (Again, think of the Green Knight, waiting on the shelf for four hundred years.) Posterity is not guaranteed; it’s not even likely; but with a completed book, a coherent album, a season of TV: at least you are TRYING.

Robin doesn’t present this as a refutation of Chayka, but it clearly represents an alternative point of view, one focused not on the public status of the maker but on the work itself. The maker recedes as the completed thing draws attention to itself. And then the completed thing makes its way into the world, and reshapes the world according to its virtue and power.

My favorite moment in The Zeal of Thy House comes in an Interlude between the first and second acts. It’s a kind of psalm, and it contains words worthy of remembrance:

Every carpenter and workmaster that laboureth night and day, and they that give themselves to counterfeit imagery, and watch to finish a work;

The smith also sitting by the anvil, and considering the iron work, he setteth his mind to finish his work, and watcheth to polish it perfectly.

So doth the potter sitting at his work, and turning the wheel about with his feet, who is always carefully set at his work, and maketh all his work by number.

All these trust to their hands, and every one is wise in his work.

Without these cannot a city be inhabited, and they shall not dwell where they will nor go up and down;

They shall not be sought for in public council, nor sit high in the congregation;

But they will maintain the state of the world, and all their desire is in the work of their craft.

great

I’m gonna beat my favorite antique drum here.

Ross Douthat asks, “Can We Make Pop Culture Great Again? — and the answer, of course, is Nope. Absolutely not. Just as our algorithmic culture enforces inflammation in the political sphere, it enforces mediocrity in the cultural sphere. Great works of art can still be made, but if they are great their social status will be marginal at best; anyone capable of appreciating them will be hard put to find them. (It’s not impossible, mind you; but it’s not easy.) And many people who could in time make great work will be deterred and, reasonably enough, give up before they get started and work instead for hedge funds.

If the truth of this assessment is not obvious to you, I’m not going to try to convince you. But I will say this: I’d bet a large sum of money that if you were to spend a year breaking bread with the dead, immersing yourself in the great works of the past, then at the end of that year the truth of my assessment would be obvious to you.

The good news is that there’s never been a better time to break bread with the dead. A vast cultural inheritance is ours for the taking, and to access is almost all we need is a computer with a web browser. We all know this, but I don’t believe we reflect on it often enough. Think of Project Gutenberg, Google Books, Google Arts and Culture, the websites of the world’s great museums, music of every kind available on dozens of platforms, the astonishing range of cultural achievement available in the BBC archives and the Internet Archive. Many of us can check out e-books from out local libraries and get access to the great collection of films at Kanopy.

Talk about an embarrassment of riches! When the algorithms are trying to sell you mediocrity (or worse) on the sole ground of its novelty, my suggestion is: Vote for something else. Vote with your attention … whenever you’re ready to stop eating grass.

December 19, 2024

five true things

All of these things are true, and by affirming or denying one you are saying absolutely nothing about any of the others. Distinguo!

December 16, 2024

unforgiven

A continuation of this post

~ 1 ~

I don’t suppose that there’s a sadder book in all the world to me than George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss. Though there are tragic elements and tragic characters in Eliot’s other novels, this book only is simply and straightforwardly a tragedy – and I scarcely know a darker one. It is like Hardy before Hardy; in many ways it prefigures Tess of the d’Urbervilles, though I find Maggie Tulliver a far more appealing figure than Tess Durbeyfield. And while Hardy can seem cold and passionless in his disposition of his dramatis personae, almost the icy voice of Fate itself, the manifest tenderness which Eliot shows to so many of her characters – even unappealing ones like Mr. Casaubon in Middlemarch – makes poor Maggie’s downfall especially hard to bear. George Eliot herself, her husband reported, wept ceaselessly as she wrote the book’s final pages; and how could she not have done so?

I speak of Maggie, though two people die at the book’s end: Maggie and her brother Tom. But Tom’s death, while it does not please me, causes me no pain or grief; Tom, to me, is one of the great villains of literature. He does not cause Maggie’s death, but he blights her life.

The tenderness that Eliot habitually extends to her characters she offers also to her readers, when she presents this as the epigraph to her book: “In death they were not divided.” In this way she gently suggests to us that at least two of the book’s major characters will die; and we don’t have to read very far into the book before we can make a very good guess about the identity of those who are doomed. We are thus given the opportunity to prepare ourselves for what is to come. It doesn’t really help, though; or anyway it doesn’t help me. But I appreciate the gesture.

There’s something else noteworthy about this epitaph: it’s a quotation, but a deliberately truncated one. The original appears in the biblical book of 2 Samuel, and is part of the song of lamentation that King David sings for two men fallen in battle: Saul, the first king of Israel, whom David replaced, and Saul’s son Jonathan, David’s dearest friend. Davis sings of them,

Saul and Jonathan were lovely and pleasant in their lives,

and in their death they were not divided:

they were swifter than eagles,

they were stronger than lions.

Thus his commendation of two men, one his sometime enemy, the other his dearest friend. This perhaps is meant to tell us a little about Eliot’s views of her two chief characters.

But there’s something more essential here: by saying of Tom and Maggie that “in death they were not divided,” she allows the correct inference that in life they very much were divided. And what divides them is Tom’s relentless cruelty to Maggie. Now, to be sure, Tom would say that it Maggie’s sins divide them, that he merely does his duty. But this is untrue. Tom is in fact not reliably dutiful. His self-image is false. When the call of duty conflicts with the impulse to be cruel, his cruelty always wins.

Very early in the novel, Tom quarrels with his scruffy friend Bob Jakin – a few rungs down the social ladder from middle-class Tom – and calls him a cheat. “I hate a cheat. I sha’n’t go along with you any more.” And thus he ends his relationship with Bob. Though many years later Bob will re-appear in Tom and Maggie’s life, Tom never would have sought Bob again, nor questioned the wisdom of his judgment against Bob. As Eliot comments at the conclusion of that chapter,

Tom, you perceive, was rather a Rhadamanthine personage, having more than the usual share of boy’s justice in him, – the justice that desires to hurt culprits as much as they deserve to be hurt, and is troubled with no doubts concerning the exact amount of their deserts. Maggie saw a cloud on his brow when he came home, which checked her joy at his coming so much sooner than she had expected, and she dared hardly speak to him as he stood silently throwing the small gravel-stones into the mill-dam. It is not pleasant to give up a rat-catching when you have set your mind on it. [Rat-catching is what Tom had planned to do with Bob.] But if Tom had told his strongest feeling at that moment, he would have said, “I’d do just the same again.” That was his usual mode of viewing his past actions; whereas Maggie was always wishing she had done something different.

(Re: the “Rhadamanthine personage,” Rhadamanthus, in Greek mythology, was a king of Crete who became a judge of the dead, and a strict and inflexible judge too.) And thus it always is. Again and again Maggie acts in ways that she comes to regret; again and again what she desires more than anything else is Tom’s forgiveness; again and again he denies it to her. Sometimes he forgets her sins, or grows tired of punishing her for them; but he never once forgives. In this he exaggerates the tendencies of his father, who not only refuses to forgive his greatest enemy but, when he thinks he is near death, commands Tom to write that refusal in the family Bible: “I don’t forgive Wakem for all that; and for all I’ll serve him honest, I wish evil may befall him.” Mr. Tulliver can think of nothing more sacred than a Bible, though he has no interest in practicing anything that might be taught therein.

Tom is his father’s son in this sense, though in others he is even stricter than his father. For instance, even when Mr. Tulliver is in great need of money he cannot make himself call in a debt his poor and unlucky brother-in-law owes him, because he he knows the pain it would cause his sister. In such a circumstance Tom would never hesitate. In the greatest crisis of Maggie’s life, when she has just barely escaped an elopement with her seducer, Tom turns her away: “You will find no home with me…. You have disgraced us all. You have disgraced my father’s name. You have been a curse to your best friends. You have been base, deceitful; no motives are strong enough to restrain you. I wash my hands of you forever. You don’t belong to me.” Further: “I have had a harder life than you have had; but I have found my comfort in doing my duty.”

You will find no home with me, no haven in a heartless world. You had to come to me — but I do not have to take you in, and I won’t.

~ 2 ~

This I think is the one truly essential point: Tom has not done his duty. He portrays himself as a man of filial piety; he prides himself on having worked hard to rescue his father from debt; he makes his father’s enemies his own. Yet here he refuses to obey the very last commandment his father gave him, in the minutes before his death: “You must take care of her, Tom – don’t you fret, my wench – there’ll come somebody as’ll love you and take your part – and you must be good to her, my lad.” (Mr. Tulliver always refers to Maggie, in the most affectionate tones, as “the little wench.”) This, when Maggie’s suffering is at its worst, Tom refuses to do — even though she had given years of her youth to caring for Mr. Tulliver, while Tom was out making a career for himself. But Tom thinks he has done his duty and Maggie has failed to do hers. This is because “duty” for Tom is a matter of public respectability, and the ascent of the social ladder. That we have a duty to charity and kindness never crosses Tom’s mind.

As I have said: Tom’s cruelty is his treasure, and where your treasure is, there will your heart be also. He delights to feel himself morally strong, and from that strength to judge those he feels to be weaker than he. When he repudiates Maggie, as he often does, it is hard not to feel that those are to him the best moments of his life: the ones in which he condemns, not his enemy, as his father had condemned Wakem, but his own flesh and blood, his own sister, who loves him more than she loves anyone and has all her life craves his approval. Tom Tulliver is not a good and responsible man who is sometimes overly strict; he is an absolute monster of cold-blooded savagery. His cruelty is limited only by the scope of his power; alas for his ego, he has only poor Maggie to tyrannize over.

Eliot says of Maggie that “she had always longed to be loved,” and that is true, but I think she longs for forgiveness even more, if indeed those two things can be divided. Perhaps she craves forgiveness as a token of love. And while from some who are dear to her she indeed receives forgiveness – that is almost the only thing that sheds light on the dark, dark road she is forced to walk – she is never forgiven by the person whose forgiveness would have meant the most to her: her brother.

Late in the book, Maggie speaks with a pastor, one Dr. Kenn – a wise and compassionate man, as his name might suggest. (Kennen in German connotes personal knowledge, what we might even call wisdom, as opposed to Wissen, which is the knowledge of facts.) Having spoken with Maggie, and having read the penitent letter of her would-be seducer, he says,

“I am bound to tell you, Miss Tulliver, that not only the experience of my whole life, but my observation within the last three days, makes me fear that there is hardly any evidence which will save you from the painful effect of false imputations. The persons who are the most incapable of a conscientious struggle such as yours are precisely those who will be likely to shrink from you, because they will not believe in your struggle.”

This is of course a shrewdly accurate summation of Tom’s attitude. And Dr. Kenn knows how widespread such attitudes are, even if they rarely appear in such undiluted malignancy as they do in Tom.

After Maggie leaves, Dr. Kenn reflects on the intractable difficulties of her situation, in a passage that quietly harmonizes the voice of Dr. Kenn and that of the author. Eliot thinks (Kenn thinks? They think?) that “the shifting relation between passion and duty” – the very problem with which Maggie has struggled and with which Tom can never imagine there being any struggle, thinking as he does that his passions are his duties – is so complex that it can have no plain general answer. We remember the Jesuit casuists, who declined to be governed by largely-framed rules and could always, it was said, find a way of avoiding an unwelcome bondage to them. (The word casuist comes from the Latin casus, case – a rule that applies generally may not apply to this case.) Such men, Eliot says, “have become a byword of reproach; but their perverted spirit of minute discrimination was the shadow of a truth to which eyes and hearts are too often fatally sealed, – the truth, that moral judgments must remain false and hollow, unless they are checked and enlightened by a perpetual reference to the special circumstances that mark the individual lot.”

It is good to despise casuistry in its usual pejorative sense, but not good to refuse the … well, the duty to make discriminations according to different circumstances. We cannot live wisely by ”maxims”:

All people of broad, strong sense have an instinctive repugnance to the men of maxims; because such people early discern that the mysterious complexity of our life is not to be embraced by maxims, and that to lace ourselves up in formulas of that sort is to repress all the divine promptings and inspirations that spring from growing insight and sympathy. And the man of maxims is the popular representative of the minds that are guided in their moral judgment solely by general rules, thinking that these will lead them to justice by a ready-made patent method, without the trouble of exerting patience, discrimination, impartiality, – without any care to assure themselves whether they have the insight that comes from a hardly earned estimate of temptation, or from a life vivid and intense enough to have created a wide fellow-feeling with all that is human.

~ 3 ~

But at this point I find myself under an unwelcome conviction. I must pause to note that Eliot says this: “Tom, like every one of us, was imprisoned within the limits of his own nature, and his education had simply glided over him, leaving a slight deposit of polish; if you are inclined to be severe on his severity, remember that the responsibility of tolerance lies with those who have the wider vision.” I shall strive to bear it in mind; but I am not confident of success.

The Mill on the Floss is Eliot’s most autobiographical novel. The scene is shifted from the West Midlands of her youth to Lincolnshire, but Tulliver family bears close affinities to that of the author, whose real name was Mary Ann (sometimes Marian) Evans. Kathryn Hughes:

Like her father and his brothers, she rose out of the class into which she was born by dint of hard work and talent. She left behind the farm, the dairy and the brown canal, and fashioned herself into one of the leading intellectual and literary artists of the day. But … she learned what it was like to belong to a family which regularly excluded those of whom it did not approve. When, at the age of twenty-two, she announced that she did not believe in God, her father sent her away from home. Fifteen years later, when she was living with a man to whom she was not married, her brother Isaac instructed her sisters never to speak or write to her again.

But though her father rejected her for her unbelief, in the last years of his life, when he could not care for himself, he expected Mary Anne to care for him. And she did. Hughes again:

At times, Mary Ann feared she was going mad with the strain of looking after him. He was not a man who said thank you, believing that his youngest daughter’s care and attention was his natural due. He was often grumpy and always demanding, wanting her to read or play the piano or just talk. During the ghastly visit to St Leonards-on-Sea in May-June 1848, Mary Ann reported to the Brays that her father made ‘not the slightest attempt to amuse himself, so that I scarcely feel easy in following my own bent even for an hour’. Trapped on the out-of-season south coast, she tried to stretch out the days with ‘very trivial doings … spread over a large space’, to the point where one featureless day merged drearily into the next.

Nevertheless,

Mary Ann’s devotion to her father never wavered. Mr Bury, the surgeon who attended Evans during these last years, declared that ‘he never saw a patient more admirably and thoroughly cared for’. Still deeply regretful of the pain she had caused him during the holy war [that is, during their conflict over her loss of religious faith and consequent refusal to attend church with her father], Mary Ann took her father’s nursing upon her as an absolute charge.

It became for a period, Hughes argues, Mary Ann’s vocation:

This makes sense of the puzzle that it was in the final few months of Robert Evans’s life that Mary Ann found her greatest ease. She was with him all the time now, worrying about the effect of the cold on his health, tying a mustard bag between his shoulders to get him to sleep, sending written bulletins to Fanny and Robert about his worsening condition. There are no surviving letters to Isaac and Chrissey, and no evidence that they shared the load with her. It was Mary Ann’s half-brother Robert who spent the last night of their father’s life with her, a fact she remembered with gratitude allher life. Yet although she declared that her life during these months was ‘a perpetual nightmare — always haunted by something to be done which I have never the time or rather the energy to do’, she accepted that she would have it no other way. To Charles Bray she reported that ‘strange to say I feel that these will ever be the happiest days of life to me. The one deep strong love I have ever known has now its highest exercise and fullest reward.’

So string was her love for her father that, she wrote in a letter as his death neared, “What shall I be without my Father? It will seem as if a part of my moral nature were gone.” Nevertheless, Robert Evans, who had managed to offer some occasional words of kindness to his daughter in his final months, was ungenerous to her in his will. (It is I think no accident that wills, and second thoughts over wills, play a large part in some of her fiction, especially in Middlemarch.)

Mary Ann was more generous to her father than he ever was to her — and not least through her portrayal of Mr. Tulliver, whose repeated expressions of affection for “the little wench” are very likely more than Mary Ann ever received from Robert Evans. She gives to that fictional father a generosity and sweetness which she rarely if ever experienced from her real one.

~ 4 ~

But Isaac Evans was a different story. As noted above, when Mary Ann started living with George Henry Lewes — who was unable to divorce his wife for complicated reasons you can read about here — Isaac cut her off completely and demanded that other members of the family do the same. Despite her attempts at reconciliation, he maintained her silence until, a quarter-century later, Lewes died and Mary Ann married a man twenty years her junior named John Cross. When he learned of this marriage, Isaac wrote to her:

My dear Sister

I have much pleasure in availing myself of the present opportunity to break the long silence which has existed between us, by offering our united and sincere congratulations to you and Mr Cross….

Your affectionate brother Isaac P Evans

The “opportunity” being her marriage — nothing less respectable could have induced him to write. Like the bank director brother of Silas in Robert Frost’s “Death of the Hired Man,” he looks upon a disreputable sibling as “just the kind that kinsfolk can’t abide.”

The generosity of Mary Ann’s reply is, to me, immensely moving: “It was a great joy to me to have your kind words of sympathy, for our long silence has never broken the affection for you which began when we were little ones…. Always your affectionate Sister, Mary Ann Cross.”

This is of course far better that Isaac deserves, Isaac with his own calculus of Deserving, Isaac with his indifference to any moral excellence he himself does not care to practice — Mary Ann’s faithful care for their dying father earned her no points from her brother. It is hard for me not to hate him, as it is hard for me not to hate Tom Tulliver. But then I hear the voice of George Eliot: “If you are inclined to be severe on his severity, remember that the responsibility of tolerance lies with those who have the wider vision.”

December 14, 2024

intellectual furnishings

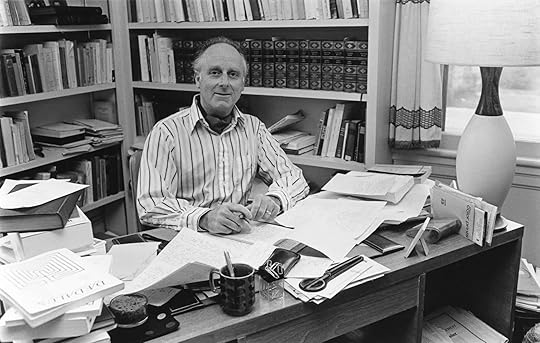

The photograph above features Victor Brombert, a professor of comparative literature at Princeton, who rates an obituary in the NYT not because of his academic career but because of what he did during the Second World War.

His personal story is a great one, but I like this photo as an exercise in the archeology of what Shannon Mattern calls “intellectual furnishings.” What might have been on a literature professor’s desk in 1985? In this case:

Books Academic journals Pen Pencil (I think that’s a pencil he’s holding, but it’s really thick — maybe some kind of editorial pencil?) Coffee mug serving as pen/pencil holder Ink blotter Home-style lamp Small Rolodex (or other brand) to hold cards with addresses Daily calendar (that’s the thing with the little stand on the back, next to the Rolodex: it shows what day it is and when you come in the next morning you tear off Yesterday and throw it away, revealing Today) Sponge for wetting postage stamps Paperweights (at least two) Magnetic box for holding paperclips Mail (under the scissors-paperweight) Envelope containing photographic prints, probably picked up from a drugstore on Nassau Street Small personal notebook (under a sheet of paper next to the coffee mug) A loop handle (next to his right forearm), presumably attached to something — a small instant camera, perhaps? The camera with which he took the snapshots he had developed at the bookstore?What’s absent? There’s no computer — there’s not even a typewriter, though there may be one elsewhere in the room. It’s possible, though, that Brombert had a secretary to type up, when necessary, his handwritten texts. I mean, the guy is wearing an ascot, and it is a truth universally acknowledged that men who wear ascots do not do their own typing.

December 12, 2024

further contributions to a demonology

Anyone who spends a lot of time online will be familiar with the sense of witnessing a collective hive-mind in action. I linked this recently with a phenomenon of widespread re-enchantment, in which re-attunement to pattern recognition via digital reading has meshed with post-atomic physics to re-open cultural space for the uncanny. And while you can think perfectly well about egregores without agreeing with any of the above, or indeed without opening any old books, it’s also true that many longstanding traditions already exist for understanding egregores – including Christianity. For example we might recall the passage in the Gospel of Mark that describes Jesus casting out multiple demons possessing a man in terms that plausibly map onto what I’m calling egregoric desire: “My name is Legion”, says this collective, “because there are many of us inside this man.”

Many of those now exploring such ideas are ambivalent on the ontology of these non-material realities. But perhaps, if we want to be able to make sense of our moral intuitions concerning a phenomenon such as Lily Phillips, we should consider not re-inventing the wheel. Bluntly: I want to consider the possibility that Phillips’ stunt is more intelligible understood not in terms of liberal feminism or the sexual revolution or whatever, but as an instance of what we might describe as egregoric capture, and the medievals would have called demonic possession.

I would refer the interested reader to an essay I wrote three years ago:

I am myself a Christian, but I do not write here to issue an altar call, an invitation to be saved by Jesus. Rather, I merely wish you, dear reader, to consider the possibility that when a tweet provokes you to wrath, or an Instagram post makes you envious, or some online article sends you to another and yet another in an endless chain of what St. Augustine called curiositas — his favorite example is the gravitational pull on all passers-by of a dead body on the side of the road — you are dealing with powers greater than yours. Your small self and your puny will are overwhelmed by the Cosmic Rulers, the Principalities and Powers. They oppress or possess you, and they can neither be deflected nor, by the mere exercise of will, overcome. Any freedom from what torments us begins with a proper demonology. Later we may proceed to exorcism.

December 10, 2024

family matters

~ 1 ~

When Christopher Lasch’s Haven in a Heartless World: The Family Besieged appeared in 1977, some critics on the Right denounced it as Marxist, while other critics on the Left denounced it as reactionary. On both sides there was, I think, a failure to understand what Lasch was primarily trying to do, which was to demonstrate the woeful inadequacy of then-current social-scientific thinking about the family — and to indicate some of the dire consequences of that inadequacy.

But the anger from the Left is certainly understandable, since Lasch really was goring some of their sacred cows. He had little patience with the then-widespread belief that women could achieve complete and completely equal integration into the workplace at no cost to anyone. (Such integration should happen, Lasch thought, but the costs needed to be inventoried and addressed.) He had even less patience with the tendency among many feminists to blame the “traditional family” for the subordinate social position of women.

In his preface to the paperback edition of his book, Lasch asks his critics, especially his feminist critics, to consider two major points. First, that “indifference to the needs of the young has become one of the distinguishing characteristics of a society that lives for the moment, defines the consumption of commodities as the highest form of personal satisfaction, and exploits existing resources with criminal disregard of the future.” And second, that “the problem of women’s work and women’s equality needs to be examined from a perspective more radical than any that has emerged from the feminist movement. It has to be seen as a special case of the general rule that work takes precedence over the family.”

By “work” here Lasch means work outside the home, work that someone else pays you to do. This is a point that Wendell Berry would later make repeatedly: that when Americans today talk about work, we always mean work that happens in the marketplace in exchange for money, and no other kind.

That second point was one that he had emphasized in the final paragraph of the book:

Today the state controls not merely the individual’s body but as much of his spirit as it can preempt; not merely his outer but his inner life as well; not merely the public realm but the darkest corners of private life, formerly inaccessible to political domination. The citizen’s entire existence has now been subjected to social direction, increasingly unmediated by the family or other institutions to which the work of socialization was once confined. Society itself has taken over socialization or subjected family socialization to increasingly effective control. Having thereby weaken the capacity for self direction and self control, it has undermined one of the principal sources of social cohesion, only to create new ones more constricting than the old, and ultimately more devastating in their impact on personal and political freedom.

For Lasch, the Left and the Right alike consider the family largely sentimentally — the sentiments from the Right being positive, those from the Left negative — rather than analytically. And Haven in a Heartless World, while being in part a contribution to that analytical task, is more fundamentally a plea to Lasch’s fellow scholars to get to work to provide a deeper understanding of the extraordinarily complex situation of the modern family.

Here again I want to invoke Wendell Berry, who made this very point at some length in his seminal 1992 essay “Sex, Economy, Freedom, and Community”:

The conventional public opposition of “liberal” and “conservative” is, here as elsewhere, perfectly useless. The “conservatives” promote the family as a sort of public icon, but they will not promote the economic integrity of the household or the community, which are the main stages of family life. Under the sponsorship of “conservative” presidencies, the economy of the modern household, which once required the father to work away from home – a development that was bad enough – now requires the mother to work away from home, as well. And this development has the wholehearted endorsement of “liberals,” who see the mother thus forced to spend her days away from her home and children as “liberated” – though nobody has yet seen the father’s thus forced away as “liberated.” Some feminists are thus in the curious position of opposing the mistreatment of women and yet advocating their participation in an economy in which everything is mistreated.

This is effectively the conclusion that Lasch came to by the end of his book: that the conservation of the family is something that can only be achieved by politically and economically radical means. (Related: that’s why Lasch, like Berry, can’t be accurately described as a liberal or a conservative. That binary opposition is useless in many contexts.)

One of the difficult questions Lasch raises is this: Why had parents, in the decades preceding the writing of the book, so often acquiesced in being sidelined? Why had they agreed to allow schools and institutions linked to schools — primarily clinical counseling of various kinds — usurp the role of formation that had once been essential to the family? Perhaps realizing that he had not clearly addressed this issue in the book proper, Lasch uses the Preface to the paperback edition to venture this idea:

The school, the helping professions, and the peer group have taken over most of the family’s functions, and many parents have cooperated with this invasion of the family in the hope of presenting themselves to their children strictly as older friends and companions.

— the idea being, Lasch thinks, to eliminate conflict from the home. A fruitless notion, says Lasch, in his quasi-Freudian mode: “The attempt to get rid of conflict succeeds only in driving it underground.”

My purpose in this post (and subsequent ones, when I can get them written) is to indicate some of the ways in which Lasch’s half-century-old book illuminates current ideas about the family — for the trends he identified in 1978 have continued to this day. And much can learned by juxtaposing the family’s complicity in its own marginalization with another point, one raised by one of Lasch’s critics from the Left. That critic, Mark Poster, rejects Lasch’s argument for the necessity of the family in these terms: “The only way to [ensure] democracy for children is to provide them with a wide circle of adults to identify with, the ability to select their sources of identification, and a separation between authority figures and nurturant figures.” (Poster published a book in the same year, 1978, that the paperback edition of Haven appeared: it is called Critical Theory of the Family and its argument is pretty much what you would expect from that title.)

There’s much that could be said about each of Poster’s criteria for ensuring “democracy for children,” but I think the key one is this: “the ability to select their sources of identification.” I believe that for Poster — and this is true of many, if not most, leftist critics of the family — the ineradicable failing of the family is simply that it is given, not chosen. From this point of view, only what the individual chooses for him- or herself can be valid for that individual. (Except in the case of race, which, as we learned some years ago from the cases of Rachel Dolezal and Rebecca Tuvel, simply though mysteriously cannot be chosen.) Poster’s user of the term “identification” is prescient, especially when one thinks of people who who say things like “I was assigned male at birth, but I identify as female.” I reject what was given and I choose otherwise. And the value of what I choose is determined wholly by the fact that I choose it. It is not something that anyone else has a right to an opinion about. (I find myself here thinking of Roger Scruton’s comment in The Meaning of Conservatism that the primary goal of liberalism is “the satisfaction of as many choices as short time allows.”)

This mode of conceiving the person can shape how people think about their families as well, something readily seen in a recent New York Times article about people who end all contact with their families. One woman interviewed in that article — who cut off her father because he demonstrated “a lack of interest in my life as I got older” — articulates the key principle of this movement: “It is not a child’s responsibility to maintain a relationship with their parent(s).” In family matters, there are no responsibilities — at least none that bind me; there — again, for me — are only free choices. It would be interesting to know whether people who adhere to this principle think that parents have any responsibilities to their adult children.

~ 2 ~

I was effectively raised by my paternal grandmother, because my mother worked long hours to keep a roof over our heads and my father was in and out of prison. He was a drunkard, and a violent one, so for me things were better when he was locked up. Not that we didn’t have good moments; you just never knew when the pivot to darkness would come. But you did know that it was coming. My mother was in a bad situation and did the best she could; but she was never an emotionally demonstrative woman, and at the end of the working day she didn’t have much energy left. Almost all of the demonstrated affection I received came from Grandma. Often she and she alone kept my head above water.

At age twenty-one, when I married the woman who has now been my wife for forty-four years, I entered a new family. I was not then merely rough around the edges — all my surfaces were abraded and abrasive, and I quiver slightly whenever I think about the conversations Teri’s parents must have had about the boy their daughter had determined to marry. Lord knows they had hoped for, and expected, someone much better than I was. But here’s the thing: once Teri’s father had said Yes to my request for his daughter’s hand in marriage — and yes, that’s how Teri wanted it: not just to give her consent, but to ask for and abide by the consent of her parents — I was his and his wife’s son. From that day forward I belonged to them just as securely and unquestionably as the children of their own marriage. I was not what they had chosen; I was handed to them not on a silver platter but on a chipped dinner plate; but they welcomed me into their home, into their life, into their hearts, and they never looked back. They could have said No; instead they said Yes, to me and all that I was and wasn’t.

It is impossible for me to overstress how much that welcome meant to me, and how determinative that was for my future. Gradually I became someone not unlike the person they would have chosen if they had been the ones choosing, and one of the most gratifying moments of my life came when I was around fifty years old, and my father-in-law — a working man from Columbiana, Alabama, a simple man with a high-school education and a great big heart — gave me one of his characteristic bone-cracking hugs, looked me right in the eye, and said: “Alan, I’m so proud of the man you’ve turned out to be.” A Nobel Prize wouldn’t have meant so much to me as that word of praise from that man.

But all this began when they accepted me without question and without reservation, and committed themselves to my flourishing, as they were already committed to the flourishing of their biological children. I truly do not know what would have become of me if not for the constancy of their love. They loved their daughter; their daughter loved me; they were therefore called to love me too. So they did. To them it was as simple as that.

Everything I think about family arises from this experience.

~ 3 ~

The phrase “haven in a heartless world” is Lasch’s but it is adapted from Karl Marx, who (in the introduction to his Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right) wrote that “Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.” Lasch’s phrase is thus more ambivalent and ambiguous than it appears to those who do not know what it borrows from, and have not grasped his long argument. That argument is: The modern economic order simultaneously creates the need for family to be a haven and prevents it from serving as a haven. (To get Marx’s argument, substitute “religion” for “family” in the previous sentence.) Lasch:

The same historical developments that have made it necessary to set up private life — the family in particular — as a refuge from the cruel world of politics and work, an emotional sanctuary, have invaded this sanctuary and subjected it to outside control.

As our socio-economic order has extended itself into what I call metaphysical capitalism, its power to penetrate and demolish all would-be havens has only increased. It strives to render us all homeless, and then to sell us the goods and services that, it is claimed, compensate for any and all losses. And homelessness is a key concept here. The comforts intrinsic to family life are those that arise from what a family at its best does, which is to make a home.

When people are groping about for a good quote about home, they typically turn to a couple of lines from a poem by Robert Frost: “Home is the place where, when you have to go there, / They have to take you in.” But the quoters rarely know the context.

Those lines come from a dialogue in verse called “The Death of the Hired Man” (1915). The participants in the dialogue are a farmer named Warren and his wife, Mary. When Warren returns from errands, Mary greets him with the news that Silas — a man who had worked for them but had departed at a time when Warren needed him — has returned. Warren had told him that if he left he could not come back; but he has come back. Silas “has a plan,” Mary says, he has ideas for how he can help them; but, she also and more pertinently says, “His working days are done; I’m sure of it.” In fact, “‘Warren,’ she said, ‘he has come home to die.’”

Warren “mocked gently” the word “home.” To which Mary:

“Yes, what else but home?

It all depends on what you mean by home.

Of course he’s nothing to us, any more

Than was the hound that came a stranger to us

Out of the woods, worn out upon the trail.”

It is in reply to this that Warren says “Home is the place where, when you have to go there, / They have to take you in.” In the context of this story it’s an ambiguous statement, leaving open the possibility that since “he’s nothing to us” they do not in fact have to take him in. Why does Silas not go to his brother, a wealthy man, “director in the bank”? What might have divided Silas from her brother is not made explicit, but Mary says, “Silas is what he is — we wouldn’t mind him — / But just the kind that kinsfolk can’t abide.” That is, precisely because he is nothing to them, Warren and Mary can accept the shiftless and feckless Silas, but his “kinsfolk” are ashamed of him, reject him: should he ever go to them, he knows, they would not take him in. So, in extremis, to Warren and Mary’s farm he comes.

In any event, Mary’s reply — never cited by quote-hunters — dissents from Warren’s way of putting the matter. She says, instead, “I should have called it / Something you somehow haven’t to deserve.” Thus Mary thinks that Silas’s brother “ought of right / To take him in,” regardless of what he deserves. Obligations to family are not, in Mary’s view, to be subjected to a calculus of deserving, even if that is precisely what “kinsfolk” tend to do.

The debate is ended when Warren, urged on by Mary, goes to check on Silas and finds him dead. The hired man has come home, or come to the nearest thing to home he could conceive. And Warren and Mary, however they may have quarreled with Silas, have become the nearest thing to family he could conceive.

Mary’s attitude towards Silas is rather like Teri’s parents’ attitude towards me: I was like a hound wandering in from the woods, nothing of theirs, but they fed me, they took me in. I was “nothing” to them until they took me in and by that very generosity made me something.

Silas’s brother, by contrast, resembles the woman I mentioned in the previous section of this essay, the one who cut off her father altogether for being insufficiently “interested” in her adult self. She has taken out the calculator of Deserving and found her father unworthy. She will not share a home, or anything of her life, with him. But we readers get the feeling, do we not, that she knows perfectly well that if she should ever have to go to her parents, they would have to take her in. They might well do so gladly, and strive to be for her a haven in a heartless world. Be that as it may, perhaps she thinks that she’ll never need such a haven — or that such a haven as she needs can be bought in the marketplace in the form of material possessions, or therapy, or even chatbot friends and companions.

About all that, time is the great teacher.

Let’s meditate on these matters for a while. I’ll return to this theme soon, I hope, in a post on George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss. It’s going to take me quite a few posts, I suspect, to put these various pieces together, but (IMO) that’s what a blog is for: tentative explorations, further developments, second and third thoughts, elaborations and corrections. Complex and difficult issues deserve such gentle treatment.

December 7, 2024

ars longa

Ten years ago I gave a talk at Vassar College and participated in some conversations with faculty of various liberal-arts colleges. During those conversations I met and had some great chats with an art historian named Andrew Tallon. We hit it off, I thought — he seemed at once utterly gentle and immensely intelligent — and I started scheming ways to get him to Baylor. I thought he would be a great conversation partner, particularly for those of us interested in Christianity and the arts — I especially wanted to introduce him to my colleague Natalie Carnes, who works on the theology of beauty. And I also thought that Andrew, who was a Catholic Christian but did not feel especially comfortable being vocal about his faith, might benefit from spending some time around people who are quite public about their Christianity.

We exchanged some emails, but eventually Andrew fell silent, and later I learned that he was gravely ill with cancer. I never did manage to get him to Baylor. In November of 2018 he died, aged 49.

When I met him, Andrew had already made a complex series of high-resolution digital scans of the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris — a building that had obsessed him since he spent a year as a child living in Paris. (His birthplace was Leuven, Belgium.) He told a journalist that “There was a biblical, a moral imperative to build a perfect building, because the stones of the building were directly identified with the stones of the Church” — that is, the people of God. “I like to think that this laser scanning work and even some of the conventional scholarship I do is informed by that important world of spirituality. It’s such a beautiful idea.” It turns out that, however diffident Andrew was, or thought he was, about his faith, that faith informed his work thoroughly.

And when the cathedral was maimed by a terrible fire in April 2019, just a few months after Andrew’s death, everyone involved in the restoration immediately realized that Andrew’s work would prove invaluable in the enormous task facing them.

So when I saw images of the completely and magnificently restored cathedral, my first thought was: Well done, Andrew. Well done, good and faithful servant. I hope you can see what you helped to make possible.

December 6, 2024

the facts don’t care about your educational philosophy

This post by Freddie is a reminder that about education he has three major points to make:

In any given population, the ability to excel academically (whether or not you call it “intelligence”) is, like almost all other human abilities, plottable as a normal distribution: that is, a few people will be really bad at it, a few people will be really good, and the majority will be somewhere near the middle. Because some people are simply better at school than other than other people, any pedagogical strategy, practice, or method that improves the performance of the worst students will also improve the performance of the best students; this means that “closing the performance gap” between the worst and best students will only be possible if you use the best strategies for the worst students and the worst strategies for the best ones — and even then the most talented students will probably adapt pretty well, because that’s what being a talented student means. (N.B. I am assuming that “Harrison Bergeron” strategies will not be employed, though maybe that’s not a safe assumption.) Another way to put it: if every student in America were equally well funded and every student equally well taught, point 1 above would still be true. Resistance to these two points is pervasive because we collectively participate in a “cult of smart” that overvalues academic performance vis-à-vis other human excellences. That is, because we value “intelligence” as a unique excellence, necessary to our approval, we cannot admit that some people simply aren’t smart. (By contrast, we have no trouble admitting that some people can’t run very fast or lift heavy weights, because those traits are not intrinsic to social approval.)Each of these three points is incontrovertibly true — indeed, if you think for a moment, the first two are blindingly obvious — but each is unwelcome to those who’d very much like to believe that equal/equal-ish/equitable educational outcomes are possible, and attainable through (a) more money or (b) better methods or (c) both. So again and again readers (a) misread, probably deliberately, Freddie’s arguments or (b) attack his character or (c) both. It would be funny if it weren’t so sad.

December 4, 2024

reasons for tolerance

There are two major reasons to practice tolerance of ideas that differ from, or conflict with, your own:

Epistemic humility: You may be wrong about some things, and even if you’re not wrong, may not fully understand your own position and may not be equipped to defend it against your opponents. Therefore you extend tolerance not only for the sake of your opponents but also for your own intellectual good. (This is a major theme in John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty.)

Political pragmatism: If you’re not powerful enough to silence your enemies, your attempts to do so may bring on a fight you can’t win. Worse, the attempt to silence others may lead to their attempting to silence you — and if they’re sufficiently strong that attempt might just succeed. And then where would you be?

In our current political moment, it is trivially easy to find strong, confident voices that confirm our opinions. And because we do not understand scale, it is easy to believe that everyone who matters, everyone who thinks, everyone who is decent is on our side. Securus judicat orbis terrarum. It is virtually impossible in such a climate to make an appeal to epistemic humility. Therefore tolerance can really only be recommended on the groud of political pragmatism.

But even this is difficult for people for whom political opponents are the Repugnant Cultural Other. As I wrote in yet another essay, “For those who have been formed largely by the mythical core of human culture, disagreement and alternative points of view may well appear to them not as matters for rational adjudication but as defilement from which they must be cleansed.” What is happening on the American left right now, in the wake of the recent election, is a struggle between political pragmatism and the deeply felt need for social hygiene.

Which will win?

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers