Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 12

March 17, 2025

a key distinction

Thesis: A cosmos in which “the heavens declare the glory of God” (Psalm 19) is the opposite of an enchanted cosmos.

March 15, 2025

distributed localism

A premonition is growing. I believe large swaths of the internet will be ceded, like it or not, to the creatures of the digital night: ghostly bots, cackling trolls, the baying hounds of attention. I imagine this future internet as a vast, boiling miasma, punctuated by signal towers poking up into the clear air: blogs & shops, beacons of reality & sincerity, nodes of a human overlay network.

So, I am planning ahead, contemplating new (old) systems that might be better suited to the media ecology & economy of the 2020s & beyond.

I couldn’t agree more, and in my own tiny way I want to join Robin in this endeavor. There are three elements to Robin’s plan:

Traditional book publishing Writing on the open web Selling and sending via the mailRobin’s celebration of the U.S. Postal Service is inspiring! — I especially like how he’s applying to his personal writing what he has learned from selling and shipping olive oil. Though that’s the one part I’m not doing. Maybe I should re-think that, but for now I’m writing books and posting to the open web.

What Robin says about the “signal towers poking up into the clear air” is a regular theme in Auden’s poetry, especially in his first years in America, as he was striving to build a community of like-minded people. Thus the comment in “September 1, 1939” that, though “Defenceless under the night / Our world in stupor lies,” still, “dotted everywhere, / Ironic points of light / Flash out wherever the Just / Exchange their messages.” Robin actually quoted that recently, noting that Auden came to disown that poem — but he didn’t disown that idea, which he has many versions of. My favorite is this, from “New Year Letter,” in which he celebrates his time visiting the Long Island house of his friend Elizabeth Mayer:

What we’re counting on is a “local understanding” that’s shared across great spaces by internet protocols and the mail. Distributed localism.

(This is of course not true localism, but is a partial compensation for the loss of strong communities; also an aid and comfort to those who have strong interests and convictions that are not shared by many, or any, where they actually live.)

More about my particular contribution to all this in a future post.

March 14, 2025

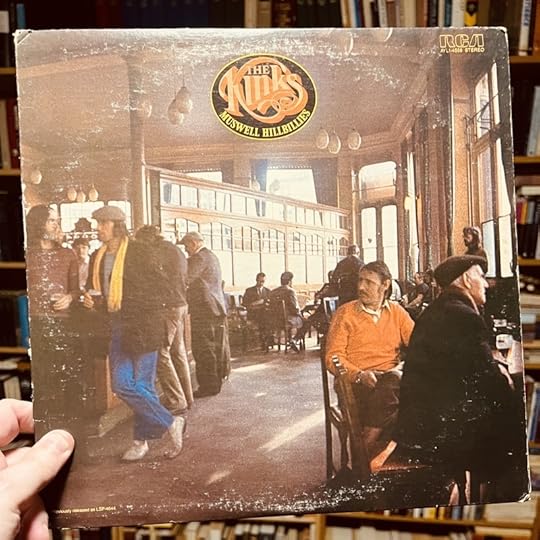

vinyl space

In the summer of 2013, when we were getting ready to move to Texas, I went through our basement storage to figure out what we would keep, what we would sell, and what we would throw away. I lingered a long time over several boxes of LPs — records that I had owned for decades, but that I hadn’t listened to in … well, in at least a decade. After a long mental struggle, I asked my son to gather up the records and sell them to Half Price Books. I didn’t do it myself because I thought I might well chicken out and bring them back home. But the age of vinyl was over, right? We’d be streaming and listening to MPs from here on out, yes?

I try not to think about what we sold that day, because over the past few years I’ve resumed listening to vinyl, and am gradually rebuilding my collection. (So far I’ve managed to keep it small — fewer than 100 discs. So far.) Some blame for this state of affairs must be laid at the feet of my friend Rob Miner, whose record collection and vintage stereo system I used to enjoy when he still lived here in Waco. Damn, this sounds good, I would think.

The online wars between the Vinyl Partisans and the Digital Defenders are endless and not worth rehashing here, or anywhere else. But in essence the Defenders point to the indisputably greater fidelity of digital recordings, while the Partisans speak more vaguely of “warmth” and “presence.” And it’s hard to speak any less vaguely! While many, though not all, music lovers believe that recordings can have distinctive “character,” it’s not clear how to identify the particular sonic features of a given recording — beyond obvious and not-especially-helpful things like dynamic range and audio spectrum.

Pascal said of the Copernican universe, “Le silence eternel des ces espaces infinis m’effraie,” and while digital recordings do not frighten me, they estrange me: they seem to be coming from a great vacuum, some featureless un-environment, a cold and boring non-place. But when I listen to a well-engineered record, especially one made in the analog era, on vinyl, I feel that I’m sharing a perceptual space, a sensorium, with the musicians. I wish I could describe it better. It’s an experience the opposite of alienating; it’s what the Germans call heimlich. Digital recordings, by contrast, often seem to be unheimlich, uncanny, slightly and uncomfortably weird.

If you don’t feel that way and feel it pretty strongly, then vinyl isn’t for you. It’s kind of a pain in the neck to use — I am not one of those people who enjoys the “ritual” of changing records; I would strongly prefer to be able to listen to a record straight through, as I do when I put on a CD. For me it’s the sound only that appeals. Well, that and the packaging: readily visible cover art! Readable liner notes!

So, yeah, I spend a lot of time wishing that I still had those records I sold in 2013. But to be fair to myself, I think most music-lovers in that year would’ve been surprised to know that in the year 2025 vinyl records would still be made at all — and thus far more surprised that they now outsell CDs.

March 13, 2025

green tea and mescaline

Here’s yet another post stemming from my reading for my biography-in-progress of Dorothy L. Sayers.

Harriet Vane is not a version of Sayers, though they do have some things in common. Both of them are writers of detective fiction with an interest in certain Victorian novelists who blended what now might be called genre fiction – tales of detection, ghost stories, other supernatural stories – with at least some of the concerns of the social novel. You see this in Dickens, of course, especially in Bleak House, where there are mysteries of identity, shocking revelations, one of the first fictional detectives, and death by spontaneous combustion; but when people talk about this kind of story, often called the sensation novel, the name most closely associated with it is Wilkie Collins, while another is Sheridan Le Fanu. Sayers wrote several chapters of a biography of Wilkie Collins — eventually abandoning it largely because Collins didn’t lead a very interesting life — while Harriet Vane, when she visits Oxford in Gaudy Night, officially does so in order to work on a book about Le Fanu.

I know Collins’s major novels, but I hadn’t until recently read much Le Fanu, and right now I’m immersed in his ghost stories or “weird tales.” (Le Fanu is often associated with the rise of “weird” fiction, as later dominated by H. P. Lovecraft, largely because two collections of his stories published after his death were titled The Watcher and Other Weird Stories [1895], and A Stable for Nightmares; or, Weird Tales [1896].)

A collection of Le Fanu’s stories called In a Glass Darkly links them to one another by presenting them as items from the collected papers of Dr. Martin Hesselius, a German physician who is interested in the convergence of certain forms of physical illness and encounters with the supernatural. He calls his speciality “metaphysical medicine.”

I may remark, that when I here speak of medical science, I do so, as I hope some day to see it more generally understood, in a much more comprehensive sense than its generally material treatment would warrant. I believe the entire natural world is but the ultimate expression of that spiritual world from which, and in which alone, it has its life. I believe that the essential man is a spirit, that the spirit is an organised substance, but as different in point of material from what we ordinarily understand by matter, as light or electricity is; that the material body is, in the most literal sense, a vesture, and death consequently no interruption of the living man’s existence, but simply his extrication from the natural body — a process which commences at the moment of what we term death, and the completion of which, at furthest a few days later, is the resurrection “in power.”

I’m not sure what he means by “resurrection ‘in power’” (though I think I know what the apostle Paul means), but the key point I want to emphasize now is this: When people experience terrifying supernatural visitations, Dr. Hesselius often traces those visitations to what the sufferers eat and drink — for instance, the story “Green Tea” concerns a man whose nightmarish experiences began when he drank too much green tea. But Dr. Hesselius thinks that these experiences, while triggered by the consumption of certain substances, are actual encounters with the supernatural. He does not explain every occult experience thus — some happen because spirits of the dead are seeking vengeance upon those who injured or killed them — but he seems always to look first to see if there is a material catalyst for the person’s affliction. Should this be the case, then he pursues a course of treatment that, by eliminating the catalyst and therapeutically addressing its effects, gradually shrinks and eventually closes the window into the demonic realm. But Dr. Hesselius never doubts that the demonic realm is real.

So you get a story introduced by our unnamed editor thus:

The curious case which I am about to place before you, is referred to, very pointedly, and more than once, in the extraordinary essay upon the drugs of the Dark and the Middle Ages, from the pen of Doctor Hesselius.

This essay he entitles “Mortis Imago,” and he, therein, discusses the Vinum letiferum, the Beatifica, the Somnus Angelorum, the Hypnus Sagarum, the Aqua Thessalliæ, and about twenty other infusions and distillations, well known to the sages of eight hundred years ago, and two of which are still, he alleges, known to the fraternity of thieves, and, among them, as police-office inquiries sometimes disclose to this day, in practical use.

When I read all this I found myself remembering Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception and its appendix, Heaven and Hell. Huxley records at great length his glorious experiences under the influence of LSD and mescaline, during which he feels that he has a direct encounter with Ultimate Reality, with the Ground of Being. This encounter poses some problems for him — for instance, ethical problems:

Now I knew contemplation at its height. At its height, but not yet in its fullness. For in its fullness the way of Mary includes the way of Martha and raises it, so to speak, to its own higher power. Mescalin opens up the way of Mary, but shuts the door on that of Martha. It gives access to contemplation — but to a contemplation that is incompatible with action and even with the will to action, the very thought of action.

But despite such reservations he never questions that what he experiences is (a) real, (b) ultimate, and (c) wonderful.

That said, he cannot help knowing that some people have bad trips — nightmarish trips, trips in which they feel that they have been exposed to something demonic, just like those characters in Le Fanu’s stories. In such matters I’m of Dr. Hesselius’s mind: as I wrote some years ago, “the porous self is open to the divine as well as to the demonic.” But Huxley is deeply reluctant to take that path, and so … well, basically he blames the victims:

Most takers of mescalin experience only the heavenly part of schizophrenia. The drug brings hell and purgatory only to those who have had a recent case of jaundice, or who suffer from periodical depressions or a chronic anxiety. If, like the other drugs of remotely comparable power, mescalin were notoriously toxic, the taking of it would be enough, of itself, to cause anxiety. But the reasonably healthy person knows in advance that, so far as he is concerned, mescalin is completely innocuous, that its effects will pass off after eight or ten hours, leaving no hangover and consequently no craving for a renewal of the dose. Fortified by this knowledge, he embarks upon the experiment without fear — in other words, without any disposition to convert an unprecedentedly strange and other than human experience into something appalling, something actually diabolical.

Huxley’s advice to those who would encounter the Ground of Being resembles Aragorn’s advice to those who would enter Lothlorien: that land is “perilous indeed, fair and perilous; but only evil need fear it, or those who bring some evil with them.” If you experience terror when contemplating the Ultimate Reality, that can only be the manifestation on a cosmic canvas of your own internal demons.

Still, having said that, Huxley continues to worry about bad trips, and returns to the subject in Heaven and Hell, in the last paragraph of which he writes,

There is a posthumous state of the kind described in Sir Oliver Lodge’s book Raymond; but there is also a heaven of blissful visionary experience; there is also a hell of the same kind of appalling visionary experience as is suffered here by schizophrenics and some of those who take mescalin; and there is also an experience, beyond time, of union with the divine Ground.

The book he refers to is an account by Lodge of how he and his wife visited a medium and made contact, they believed, with their son, who had been killed in the Great War. Having read the book, I see that it describes several different kinds of “posthumous state,” so I have no idea what Huxley is talking about. Perhaps — this is only a guess — he’s referring to the matter-of-fact ordinariness of Raymond’s reports from the Other Side. Huxley’s point seems to be that it takes all kinds to make an afterlife.

But I noticed in Raymond something that intrigues me, something that reminds me very much of Huxley’s own views on what Lewis’s Screwtape calls the Miserific Vision. Late in the book Lodge summarizes what several spiritualist writers have said about the world to which the dead go, and one of them, whom he quotes at length, says this:

“Cease to be anxious about the minute questions which are of minor moment. Dwell much on the great, the overwhelming necessity for a clearer revealing of the Supreme; on the blank and cheerless ignorance of God and of us which has crept over the world: on the noble creed we teach, on the bright future we reveal. Cease to be perplexed by thoughts of an imagined Devil. For the honest, pure, and truthful soul there is no Devil nor Prince of Evil such as theology has feigned…. The clouds of sorrow and anguish of soul may gather round [such a man] and his spirit may be saddened with the burden of sin — weighed down with consciousness of surrounding misery and guilt, but no fabled Devil can gain dominion over him, or prevail to drag down his soul to hell. All the sadness of spirit, the acquaintance with grief, the intermingling with guilt, is part of the experience, in virtue of which his soul shall rise hereafter. The guardians are training and fitting it by those means to progress, and jealously protect it from the dominion of the foe.”

Isn’t it pretty to think so?

March 11, 2025

on Pygmalion

One way to interpret the story of Pygmalion, it seems to me, is to see it as a tale in which the monster wins — because Henry Higgins is, quite obviously, a monster. The darkness of the story can be felt more strongly in the 1938 film version than in the play, largely (though not wholly) because of the magnificent performance of Wendy Hiller, in her first film role, as Eliza. I’ll consider the key differences between play and film later, but I won’t say anything about My Fair Lady, which is effectively a different thing.

The story is, I guess, still widely known. When Henry Higgins, the great scientist of phonetics, meets a poor flower-seller named Eliza Doolittle in Covent Garden, he bets his new friend Colonel Pickering that in just a few months he can transform her speech so completely that even the snobbiest of snobs won’t be able to tell that she’s not one of them. Thanks to Eliza’s smarts and skills, Higgins wins that bet. (Marginal notation: Eliza is typically called a Cockney, but whether that’s right or not depends on how you define “Cockney”: the strictest definitions confine the term to the East End of London, but Eliza is from Lisson Grove in the City of Westminster. In what follows I will use “Cockney” to mean a style of spoken English shared by many Londoners of the working classes: whether or not Eliza is a Cockney, she speaks Cockney.)

Back to the Monster: Henry Higgins’s behavior in this movie, and in the play, is so bad that you find yourself casting around for a character to notice it. For much of the story the only plausible candidate for Conscience here is Henry Higgins’s mother. Colonel Pickering is certainly kinder to Eliza than Higgins, and this is true throughout the play/film: in the first scene, when an accusing crowd gathers around Eliza, he defends her, and when Higgins is trampling her he asks Higgins to consider the possibility that the girl has feelings. (Higgins considers it and decides that she doesn’t.) But after Eliza triumphs at an elegant ball, charming everyone and dancing with a prince, when they return to Higgins’s flat to celebrate, Pickering ignores Eliza about as completely as Higgins does. It is only Higgins’s mother who suggests, later, that they might have thanked Eliza for all the work she did to win Higgins’s bet for him. But Higgins does not thank her, and he does not apologize for her months of verbal abuse. There’s only one moment when he acknowledges her quickness and resourcefulness, and he does so out of her hearing. It is only Mrs. Higgins who criticizes her son for his bad behavior; Pickering is perhaps a little too afraid of him to do so. But any criticism he receives is mild in comparison to what he deserves — at least until the final minutes.

Now, about Eliza herself. Wendy Hiller got an Oscar nomination for her performance, and of course she should have won; perhaps her status as a newcomer worked against her. It’s difficult to overstress how great she is here, in an exceptionally challlenging role. At the outset she’s doing broad comedy and doing it fabulously, but then she has go go through several stages of development.

First of course she’s a poor lass who talks pure Cockney, easy enough for a reasonably skilled actress to mimic. But then, as Eliza undergoes her training, Hiller has to overlay a labored R.P. on Cockney vocabulary and diction — which, by the way, leads to the funniest moment in the whole movie, when as she leaves a tea party the besotted toff Freddy (about whom more later) asks her if she’s walking across the park: she replies with her newly-acquired cut-glass diction, “Walk? Not bloody likely! I’m going in a taxi.” Watch the whole scene and on the basis of that alone you’ll be ready to give Wendy Hiller every Oscar statuette ever made.

Eventually Eliza matches her grammar to her new accent; and finally — this is the most astonishing thing about Hiller’s performance — in a moment of great emotional distress she loses her grip on her training and partly regresses to her native speech, wavering between her recent acquirements and her whole personal history. Higgins loves to hear this, because he treats it as proof that her changes are superficial and that she will always remain the “guttersnipe” he likes to say she is. (In the play he calls her an “impudent slut.”) He wants at one and the same time to celebrate his great achievement and to dismiss it as little more than putting lipstick on a pig.

It’s not just vocally that Hiller excels. Throughout the whole ballroom scene, and especially as she’s dancing with every eye on her, she seems to be in a dream — at one and the same time committing to the role demanded of her but also comprehensively dazed by the coming-true of a poor girl’s fantasy. And afterward, as Higgins rejoices and Pickering (though he has lost the bet) shares hie delight, Eliza looks absolutely devastated, and we can see that’s she is not merely exhausted from the demands of her command performance, but also is just beginning to realize how few genuine choices now lie before her.

She has seen a world of elegance, beauty, and plenty, and, should she go back to her old life selling flowers on the streets, or even should she achieve her former ambition of working as a clerk in a flower shop, she won’t be able to forget everything she now knows. Near the end, Higgins’s casual demand that she fetch his slippers and become a kind of servant to him infuriates her, and Freddy’s obsessive puppy-like love for her brings no comfort. It seems clear that she has come to love Henry Higgins, though it’s not clear just what kind of love it is. Would she want to marry him? Or does she simply want to force him to treat her as a human being?

After their big blow-up, in the final scene of the movie she returns to his flat. But why? She doesn’t say. And with his back to the camera, Higgins once more, in a light-hearted tone, tells her to fetch his slippers. The End.

So does the monster win? Will Eliza fetch Henry’s slippers? Or will she walk out on him again as a hopeless case? Does he mean it jokingly, or does he mean it as a final refusal either to apologize or to treat her with courtesy? It’s hard for me to see this as anything but Henry’s reassertion of his contempt for Eliza, and if I could write my own ending for the film I’d have her fetch the slippers, set them on fire, and shove them into his eye-sockets. But that’s just me.

In any case, the filmmakers are leaving room for us to think that Henry is making light of his earlier fight with Eliza in order to create room for reconciliation. This is more than Shaw had done in the 1913 play, which ends with Eliza refusing to be his servant and stomping out of his house and maybe his life, after which Higgins dismissively insists that eventually she’ll do as she’s told. Curtain.

But even that was not sufficient to dissuade audiences who wanted to believe that Higgins and Eliza would eventually marry. Still less would the film’s ending do so. Shippers gonna ship. What shall we call their image of the characters’ future? How about: The Shipping Forecast.

In any event, this kind of response bothered Shaw sufficiently that he ended up writing an epilogue in which he effectively said to the shippers: Not bloody likely.

What is Eliza fairly sure to do when she is placed between Freddy and Higgins? Will she look forward to a lifetime of fetching Higgins’s slippers or to a lifetime of Freddy fetching hers? There can be no doubt about the answer. Unless Freddy is biologically repulsive to her, and Higgins biologically attractive to a degree that overwhelms all her other instincts, she will, if she marries either of them, marry Freddy.

And that is just what Eliza did.

Shaw actually writes the outline of a second play, or maybe a novel, in which Freddy and Eliza marry and start a flower shop; in which Freddy’s family is reconciled to the marriage through reading the more hortatory works of H. G. Wells; and in which — this is my favorite part — Colonel Pickering “has to ask her from time to time to be kinder to Higgins.” And you know what’s great? She doesn’t do it. I would love to see that play or movie, for sure.

I feel so strongly about all this largely because of Wendy Hiller’s magnificent performance — and especially that moment of bleak collapse after the ball, when, as Higgins capers about in triumph, she feels that she has lost everything. It’s one of the most memorable moments in film and drama, for me. It’s wondrous what a great actor can do to transfigure a scene without saying a single word, in Cockney or R.P. or anything else.

March 7, 2025

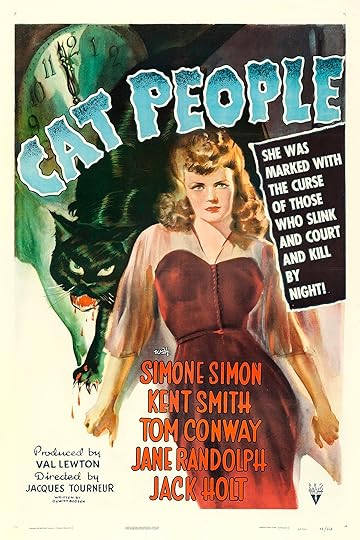

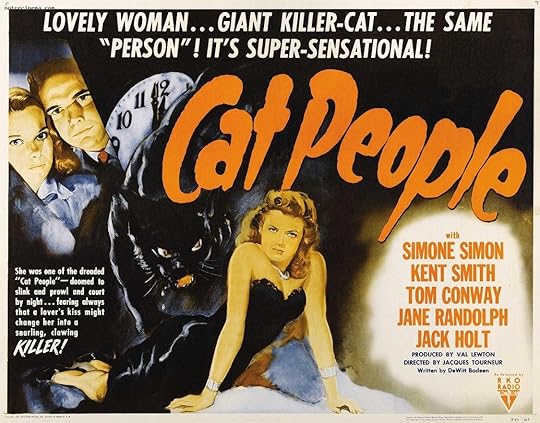

Cat People

It’s clear that the people who did the marketing for Cat People (1942) didn’t know what happens in the movie — or maybe just didn’t understand it. They made Simone Simon look sultry and dangerous:

But in the movie mainly she looks like this:

A neatly, modestly dressed young lady who is slightly worried — worried that if she is sexually aroused she will turn into a black panther and kill the man who wants to be intimate with her. (This is explained, sort of, by her being descended from Serbian cat people. At one point in the movie a very catlike woman addresses her, in Serbian, as moja sestra — “my sister.”)

All this is usually seen, by nod-nod-wink-wink viewers and critics, as an allegory for the fear of sex. But it’s a little more complicated than that. Three times in the film we see — well, actually we don’t see anything: this is a Val Lewton film, and the guiding principle of Lewton’s horror films is that you’re more afraid of what you imagine than what you directly perceive.

So: three times in the film Irena turns into a panther. (Maybe four, but it would be a total spoiler to get into that question.) The first one happens when she comes to suspect that her husband — whom she will not have sex with or even kiss: their physical relationship seems to max out at sitting next to each other at a restaurant — is growing close to Alice, a woman he works with, sometimes late into the evening. Her suspicions, not incidentally, are justified. Once Irena follows Alice along a dark city street, the women’s heels clicking on the sidewalk … but then the clicking of Irena’s heels stops, after which slight rustling sounds are heard in nearby overhanging bushes. (The sound design here is terrific, and the scene ends with what may well be the very first jump scare in movie history.)

Later, Irena follows Alice into a Y.W.C.A, where Alice regularly swims. Here’s a clip — in which, by the way, we see Jane Randolph’s Alice in a wet swimsuit, in contrast to Irena’s consistently buttoned-up style. (The movie thus sexualizes Alice and desexualizes Irena, which is just what the marketing people couldn’t understand. They obviously figured that Irena was catlike in a sexually predatory sense.) When Alice hears strange sounds around her, she leaps into the pool to get away, is eventually confronted by human-Irena, and when she emerges, discovers that her robe has been torn to shreds by something with claws.

The third transformation is the most interesting one. Irena has agreed to see a psychiatrist, who tells her that her fear is irrational — and then seeks to prove it by seducing her. He kisses her, and then … well, let’s just say that wasn’t his best play. But the key point, it seems to me, is that she is obviously not aroused, nor interested, nor even pleased. See for yourself.

So: while the general context of Irena’s transformations is the realm of sex, she never transforms because she experiences sexual desire, but rather because she experiences jealousy and anger. That is to say, Irena’s problem is not sexual passion but rather passion more generally: unbridled emotion, emotion that we suffer (Latin passio, yielding the English “passive”) rather than control. This I find curious, and I suspect that the Hays Code was responsible for this generalization — a generalization amounting to misdirection. Perhaps the filmmakers didn’t dare show Irena being turned on by her husband and having to struggle against it, and aroused by the kiss of her suave psychiatrist. Or were they trying to show a character so deeply sexually repressed that her sexuality could emerge only through other emotions? If the latter, then maybe the Hays Code actually worked in their favor.

One last point, on a related matter. In the Lewton horror films of the Forties, there are several characters like Irena: let’s call this type the Unsuitable Wife, the woman who blocks the male lead from marrying the Normal Woman he loves and is obviously meant for. Oliver can’t marry sexy Alice as long as sexless Irena is in the way. (The locus classicus for this theme is obviously Jane Eyre.)

A different version of the same problem appears in I Walked with a Zombie (1943): poor Paul is clearly attracted to his wife’s nurse, but how to get rid of the wife? She’s a zombie, after all. Can’t have sex, or even companionship, with a zombie, and murdering her would be complicated — as well as immoral, of course. Jessica is not a zombie in the George Romero sense, but nevertheless is locked away in her own wing of a compound, sort of like Ed at the end of Shaun Of The Dead but not as much fun.

And in The Seventh Victim (also 1943 — Lewton’s studio worked fast) poor Gregory is married to a Satanist when the woman he really loves is the Satanist’s cute kid sister. About that … I don’t mean to be judgmental, but if you marry a woman without knowing that she worships the Devil then maybe your engagement wasn’t long enough.

In each case we’re encouraged to think: Ah, wouldn’t it be great if the Unsuitable Wife died and left the guy free to marry the Normal Woman and get it on with her? And in each case we get what we wish for. Call it the Hollywood version of no-fault divorce.

March 5, 2025

words, words, words

I’ve read several detective novels by Freeman Wills Crofts, and my one most constant thought is: He is an utterly inept writer. His style only occasionally rises to the level of woodenness, and is usually sub-wooden. Like charcoal, maybe: dry and brittle, no longer alive, an ex-style.

Here’s a typical passage, from Antidote to Venom (1936):

His thoughts swung round into a familiar channel. If only his old aunt would die and leave him her money! She was well-to do, was Miss Lucy Pentland, not exactly wealthy, but obviously with a comfortable little fortune enough, and she had on more than one occasion told him that he would be her heir. Moreover, she was in poor health. In the nature of things she could not last very much longer. If only she would die!

Surridge pulled himself up, slightly ashamed of himself. He did not of course wish the old lady any harm. Quite the reverse. But really, when people reached a certain age their usefulness was over. And in his opinion she had reached and passed that stage. She could not enjoy her life. If she were to die, what a difference it would make to him!

Next chapter:

Then there was his aunt’s legacy. He did not know what she was worth, but it must be several thousand: say seven or eight thousand at the most moderate estimate. And at her death he would get most of it — she had told him so. What, he wondered, would his share amount to? After death duties were deducted and one or two small legacies to servants were paid, there should be at least five thousand over. Five thousand! What could he not do with five thousand? Not only would it clear him of debt, but he could get that blessed car for Clarissa as well as several other things she wanted. They could take a really decent holiday; she had friends in California whom she wished to see, and for professional reasons he had always wanted to visit South Africa. In countless ways the friction and strain would be taken from his home life. And all this he would get if only the old lady were to die! Last night she had looked particularly ill; pale like parchment and more feeble and depressed than he ever remembered having seen her. Again he told himself that he didn’t wish her harm, but it was folly not to recognise facts. Her death was the one thing that would set him on his feet.

Later:

With growing frequency his thoughts turned towards his aunt, Lucy Pentland. If only he could get that money that was coming to him, not at some time in the distant future, but now! Not only would it remove this ghastly financial worry, but it would mean greater safety in every way. With more money he and Nancy could take better precautions.

She could give up that wretched job of hers and go and live in decent surroundings in some place in which he could visit her. A tiny cottage somewhere with a garden and roses on the porch! He grew almost sick with desire as he thought of it. And it might become a possibility — if Lucy Pentland were to die.

We get it! He wants his aunt to die! Enough already! And there are five or six more passages just like this. You can almost see Crofts bent over his desk, gripping his pen fiercely, muttering to himself Must … make .. motivation … clear. And he does, with one calcified stock phrase after another.

But of course what Crofts is famous for is the mechanics of plot — and in this novel the means of one death is so arcane and intricate that we need not only a map (of a zoo, as it happens) but also a detailed diagram of the device employed:

In other news, Fang Apparatus is the name of my new band.

Speaking of bands, and bear with me as I develop this comparison, but in a way Crofts reminds me of Roger Waters. Waters has said that in Pink Floyd he and Nick Mason were the group’s architects while David Gilmour and Richard Wright were the musicians. Sometimes when he tells this story he complains that Gilmour and Wright looked down on him; other times he insists that the architects are the real bosses because you can always hire musicians — they lie thick on the ground, but an architect is a rara avis. (Waters actually studied architecture before turning to music.)

Crofts too is an architect, and puts all his best energies into construction. He couldn’t be bothered with the music of language, with wit, with nuances of character; he didn’t see those as essential to success in writing a detective story. Even though Crofts was a religious man, when he brings a religious theme into Antidote to Venom he treats it as quickly and cursorily as possible; he seems embarrassed to have brought it up.

Me, I’m a music guy, in fiction and actual music alike. If I had to choose between Waters/Mason and Gilmour/Wright, I’m taking the latter pair every time: their contributions to the Floyd seem to me to dwarf those of Waters, who, given his freedom, inevitably sank into dreary pretentiousness and tub-thumping. If he had been a novelist, he’d have written over and over and over, “If only she would die!”

March 3, 2025

method and madness

I think often of a passage from Patricia Hampl’s gorgeous memoir, The Florist’s Daughter. Scattered through the book are images of her father, short films as it were that emerge from memory. Here’s my favorite one:

He’s in the design room, just off the first greenhouse where all the shiny green plants are kept. He’s holding a knife, the pocketknife every florist has in his pocket at all times, the knife that is never loaned to anyone else.

It must be a Sunday afternoon. The greenhouse is closed, the design room silent. He’s getting something ready, no doubt for a funeral or the early-Monday hospital delivery round. I’m sitting on the stool by the design table, as I always do, just watching.

He emerges from the walk-in cooler with an armload of flowers — tangerine roses and purple lisianthis, streaked cymbidium orchids, brassy gerbera daisies and little white stephanotis, lemon leaf, trailing sprengeri fern, branches of this, stems of that. He tosses the whole business on the big table, and stands in front of what looks like a garbage heap. An empty vase is set in front of him. He appears to ignore it. He just stands there, his pocketknife in his hand, but not moving, and not appearing to be thinking. He doesn’t touch the mess of flowers, doesn’t sort them. He just stares for a long vacant minute. He’s forgotten I’m sitting there.

Then, without warning, he turns into a whirlwind. Without pause, grabbing and cutting, placing and jabbing, he puts all the flowers into the vase, following some inner logic so that — as people always said of his work — it looks as if the flowers had met and agreed to position themselves in the only possible way they should be. He worked faster than anyone else in the shop, without apparent thought or planning. I could distinguish his arrangements — but they weren’t anything as artificial as an “arrangement” — from across the room from the dozens lined up on the delivery table for the truck drivers.

(What a writer Hampl is.) Now, I am no artist — it seems that Hampl’s father was an exceptional artist indeed — but there is something here that reminds me of my own working methods. I often hear about writers who write 500 words a day, come rain or sleet or snow or Breaking News. And that’s admirable! But I have never written that way and never will.

Now, to be sure, I always have at least one and usually two writing projects going on, and I’m working on something almost every day — but the working doesn’t always mean writing words. I can’t write words until the words are ready to be written, and sometimes they might not be ready until I’ve read and re-read books, until I’ve made and then deleted and re-made outlines, until I’ve re-ordered my index cards in half-a-dozen ways, or — this is most common — until I’ve just sat in my chair and thought for a long time about what I need to say. Then I write.

So it’s not uncommon for me to go ten days or even two weeks without writing a single word that ends up in the book or essay I’m working on, and then write 6000 words in a morning. I’ve learned not to force it, I’ve learned to recognize the symptoms of readiness — and maybe more important, learned to note and heed the absence of such symptoms. Whenever I have tried to do the 500-words-per-day thing I’ve just ended up with more stuff to delete. My job, as I understand it, is to wait patiently and be ready when the words are ready.

I don’t recommend this method to anyone else. It’s simply the only one I’m capable of following. And I describe it here only because it may be encouraging to some other people who feel guilty about not being able to be perfectly regular in their habits. It’s possible to follow a practice that looks highly inconsistent and irregular and yet, over the long haul, ends up being consistently fruitful.

February 28, 2025

retirement

Universities love to have productive senior faculty, and when they can they pay such faculty well — but they also don’t really mind when the people near the top of the salary ladder retire. (I say “they,” meaning primarily the people who handle the budgets.)

Here at Baylor there’s been a program in effect for the past few years that gives a gentle nudge to people trying to decide whether it’s time for them to retire. If a person eligible for retirement gives two years’ notice — and does so by signing a binding contract! — then the university

provides a nice little cash bonuspromises a decent pay increase for each of the faculty member’s last two yearsexempts the faculty member from service on committeesallows the faculty member, in his or her final year, to (a) teach half time for the whole year or (b) teach full time for one semester and take the final term as a farewell sabbaticalI never seriously considered this option — thinking of myself as, if not a young whipper-snapper, then at worst a semi-grizzled veteran — until I learned that the year 2024 marked the end of the program. I could take advantage of it then or say goodbye forever to the cash bonus, the sabbatical, and (above all) the exemption from committees. And in any case I’m not that far from retirement….

So I signed up.

My most recent paycheck contained the lagniappe. Then, just this week, I got an email from Baylor’s Committee on Committes asking me to fill out a form identifying the committees I am serving on, the ones I would be willing to serve on, etc. I clicked the link and the first page gave me a series of options by which I could identify my status. One of them was “I have signed a retirement contract.” I clicked that one and the next screen of the questionnaire bade me a courteous farewell. At that moment I knew I had made the right decision.

When I retire, in December 2026 (though I will be paid through May 2027), I will have been teaching for forty-four years — and I love teaching as much as I ever have. My students are a joy to me, they really are. With a few exceptions, of course, let’s be honest.

But the increasing bureaucratization of the university is the opposite of a joy — it is a misery. The endless and often incomprehensible online forms (many of them obviously designed by trainee or incompetent programmers); the annual online “learnings” (shudder) about Title IX, racism and sexism, travel policies, etc. etc.; the Finance Officers and Accommodation Offices; the annual enrollments in ever-changing health insurance policies … all this has worn me down, and the genuine joy I experience in teaching is being overwhelmed by these characteristic demons of late modernity. I’m ready to quit.

Or was at the time I made the decision; the prospect of Elon and his merry pranksters blowing up Medicare was not yet on anyone’s bingo card when I had to make the call. If it had been, I very likely would have chickened out. The deed is done, so I can say is what I often say: Fare forward, voyagers.

And — this is something I think about a lot — maybe my retirement will mean one more job for a highly-qualified humanist in a terrible job market. Of course, I might not be replaced at all … or I’ll be replaced by a scientist or an engineer or a marketing consultant … but there’s at least a chance that I’ll be replaced by someone who loves literature and ideas. Someone better qualified than I was when I entered the workforce all those years ago, but a kindred spirit who might not otherwise find a tenure-track position. One can but hope.

But after all these decades of teaching, how will I cope without the foundational temporal structure of my life for the past sixty years: the annual round of the blessed School Year? Honestly, I don’t know. I’m hoping that I will finally be fully governed by the rhythms of the church year.) At the moment all I’m really thinking about is the books and essays I may now finally have time to write — perhaps that time will compensate for the loss of structure — and the loss of regular human connection, especially with young people who have not yet become jaded.

I have always thought that one of the greatest moments in all of literature, in all of human art, comes at that point in The Tempest when Miranda — who all her life has known only her father, Caliban, and Ariel — sees the party of the Milanese court approaching and cries, “O brave new world, that hath such people in it!” To which Prospero: “‘Tis new to thee.” What makes the moment so absolutely brilliant is that both of them are right. We really need both ways of viewing the human creature. But what will I, a ragged and grumpy old Prospero, deprived of staff and book, do without my Mirandas?

February 26, 2025

dueling letters

Those of you uninterested in Wheaton College or in Christian higher education more generally — which is to say, most of you — should feel free to skip this one.

So the open letter by Wheaton College alumni denouncing the school for capitulation to wokeness, which as I write has 1277 signatories, has been countered by an open letter by Wheaton College alumni denouncing the school for failing to repudiate Project 2025, which has 1653 signatories.

I therefore declare the lefties the winners of this referendum!

Just kidding. I do, however, have some thoughts.

I notice that while the first letter (“For Wheaton,” hereafter FW) denounces Wheaton for allowing “unbiblical” practices to occur on campus, it does not actually cite the Bible. The other letter (“Open Letter,” or OL), by contrast, cites thirty-six passages from Scripture. Hey FW, you seriously need to raise your game in this regard.

FW is pretty explicit in what it wants, most notably “an audit of every single faculty and staff member’s commitment to the Statement of Faith and Community Covenant” — an interesting idea, since it directly copies Ibram X. Kendi’s old plan for every university to have an “antiracism task force” appointed by university administrators and unaccountable to standard procedures of governance. I wonder how such an audit would work. Would the task force decide in advance what is and is not biblical and seek to dismiss those who disagree? Could those whose views are deemed unbiblical defend themselves by citing relevant scriptures? What happens to people who fail their audit?

OL is less programmatic, but it says that Project 2025 is “antithetical to Christian charity” and that “Silence in the face of such an anti-Christian vision is complicity.” So presumably (?) this means that Wheaton should denounce Project 2025 rather than be “complicit” in it. But what is “Wheaton” in this scenario? The President? The administrative cabinet? The Board of Trustees? And what to do with faculty or staff who think that Project 2025 is perfectly consistent with Christian orthodoxy?

Five years ago I wrote that there are two political parties in America today: the Manichaeans and the Humanists. It seems to me that FW and OL alike belong to the Manichaean Party; they just represent two mutually-hostile wings thereof.

More specifically, it seems to me that both sides here — but FW more belligerently, in “tough negotiator” mode — are demanding the same thing of Wheaton: Tell me that God endorses my politics. But I don’t think Wheaton will do that, because it’s foundationally built on the idea that people who affirm its Statement of Faith and Community Covenant will not agree about everything in the political and social and personal and even the theological realm but will be able to argue charitably and constructively on the basis of their shared commitments — which are substantial indeed, but not without controversy.

If people at Wheaton can disagree about when Christians should be baptized, about the proper form of church governance, about predestination and election, about the role of the Holy Spirit in the Christian life, you’re going to tell me that there’s no room to disagree about DEI initiatives and immigration policy? If so, then you’re placing political unanimity above theological conviction, and — I have to consider this possibility — that just may say something about what your actual core commitments are. And if your political commitments are non-negotiable, then maybe — probably — almost certainly — Wheaton isn’t the place for you and you should devote yourself to some other institution. Wheaton is a place where faith seeks understanding; those of you who have already solved all the problems that beset the political realm and don’t want to face disagreement likely would be happier at a more seeker-unfriendly institution.

If Wheaton ceases to orient itself to controversy and disagreement in the way it historically has, then I don’t know what its raison d’être would be. To settle this mess by taking one side or the other would be to yield a great victory to the Manichaean Party at a great cost to Christian charity. That may be tempting to the people who run Wheaton simply because Manichaeanism is increasingly dominant on our political scene, but, for one thing, I don’t think that it will always be so dominant, and, for another, I don’t think Wheaton’s survival at that price would be worth it. What does it profit a college to achieve political unanimity but lose its soul?

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers