Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 116

May 17, 2022

welp

More than twenty years ago Malcolm Gladwell published a fascinating essay about two different modes of failure in sports: panicking and choking. “Panic … is the opposite of choking. Choking is about thinking too much. Panic is about thinking too little. Choking is about loss of instinct. Panic is reversion to instinct. They may look the same, but they are worlds apart.” Over the past decade, Arsenal have become masters of both modes of failure. When a player flies into a late tackle or drags down an attacker, he’s panicking (hello Xhaka, hello Rob Holding), but what happened to the side yesterday was a unanimous collective choke: when they needed a solid performance, everyone became paralyzed.

Arsenal are like the Ship of Theseus: All the players change, all the front office people change, nothing is what it was a decade ago … except the panicking and choking. Those endure. It’s a mystery to me, but if you’re going to be an Arsenal supporter you have to learn to live with it, because it’s hard to imagine it changing — it’s part of the DNA of the club now.

I’d prefer to be a supporter of any other kind of club, but it’s difficult (I’m inclined to say impossible) to choose these things. You end up emotionally attached to a team for reasons unknown and probably unknowable. So I would drop Arsenal in a second if I could, and turn, not to a better club, but a less neurotic one. But I don’t think I can.

this is your brain on shuffle

Every morning — and I mean every single morning — when I awaken from slumbers, my brain serves up a song. A different song each day, as a rule. Never merely a chune, as the Scots fiddlers would say, but always a song with words, and usually a pop song from any time in the past fifty years. Rarely it’s a hymn, and even more rarely a pre-Sixties pop song; but from within that fifty-year window it can be pretty much anything, including songs I haven’t thought of in years or even decades. A few times it’s been a theme song from an old TV show.

The only exceptions to the Random Shuffle Rule come when I’ve had a song on heavy playing rotation. For instance, last year when I was obsessed with Big Red Machine’s gorgeous “Phoenix” it became my morning song on several occasions. But typically what turns up as I lift my head from the pillow is a surprise and I love that.

This morning it was “Gates of the West” (a neglected little gem, that one); yesterday it was “Mykonos”; and that’s all I’m going to say. I’ve never actually written or (except to my family) spoken about this oddity of mine, and I’ve never made a record of the songs — I’m superstitiously afraid that any such documentation will put an end to the service. So this post is as far as I’m willing to go in self-revelation.

But I mention it because I wonder how many other people have something like it — a central element of daily experience that no one else (or hardly anyone) knows about. Some quirk, some habit, whatever; but something that for you is a major feature of life even though no one would have any way of knowing it.

May 16, 2022

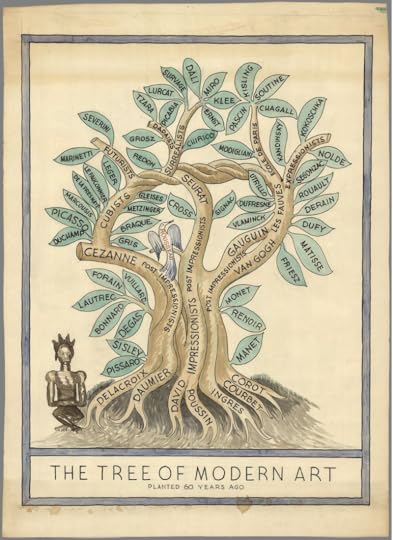

Miguel Covarrubias, The Tree of Modern Art (1940)

reification and metaphysical capitalism

I’ve written occasionally here about what I call “metaphysical capitalism” — see the relevant tag at the bottom of this post — but one thing I have neglected to note is that one of the most powerful elements of the Marxist critique of capitalism has been the argument that it is the nature of modern capitalism to extend its understanding of the world into the personal, the emotional, the spiritual — in general the metaphysical realm.

A key text here is George Lukács’s famous essay on “Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat,” where he writes of “the split between the worker’s labour-power and his personality, its metamorphosis into a thing, an object that he sells on the market.” This happens in varying ways in the varying professions of the capitalism world; for instance, in any bureaucracy:

The specific type of bureaucratic ‘conscientiousness’ and impartiality, the individual bureaucrat’s inevitable total subjection to a system of relations between the things to which he is exposed, the idea that it is precisely his ‘honour’ and his ‘sense of responsibility’ that exact this total submission all this points to the fact that the division of labour which in the case of Taylorism invaded the psyche, here invades the realm of ethics.

And when Taylorism conquers both the psyche and ethics, we get self-Taylorizing — the complete internalization of metaphysical capitalism and the consequent redescription of a condition of enslavement as a condition of self-making. People come to believe that they’re expressing themselves on social media when in fact they’re doing Mark Zuckerberg’s bidding for free. They’re like Eloi thinking that they’re the masters of the Morlocks when in fact they’re merely food.

What I found especially interesting in my re-read of Lukács (for the first time in many years) is his demonstration that this commodification of the human person goes back a long way, much longer than we might typically think. For instance, he notes that in the Metaphysics of Morals (1797) Kant defines sex and marriage in the most commodified way imaginable: “Sexual community is the reciprocal use made by one person of the sexual organs and faculties of another,” while marriage “is the union of two people of different sexes with a view to the mutual possession of each other’s sexual attributes for the duration of their lives.” Lukács comments, “This rationalisation of the world appears to be complete, it seems to penetrate the very depths of man’s physical and psychic nature.” It’s capitalism all the way down.

I am anything but a Marxist, but it’s important for me to realize (however belatedly) that some of my own recent arguments were anticipated by Marxist thinkers a hundred years ago. I should probably be making better use of that critique — if not of their suggestions for what should replace capitalism.

May 14, 2022

I was very interested in this Jonathan Malesic essay on h...

I was very interested in this Jonathan Malesic essay on how college students are or are not coping with the stresses of Covidtide. For what it’s worth — all such reports are anecdotal, but, despite what people say, the plural of anecdote is data, when there are enough anecdotes and they’re read with sufficient intelligence — my Honors College students have been much more like those at the University of Dallas than the ones at SMU, where Malesic teaches. I have been consistently surprised and gratified by how cheerfully and competently my students have navigated the various complexities of this era. Indeed, they’ve handled it all with considerably more grace than I have. I can’t be sure why they’ve managed so well, but I think it has something to do (in many cases anyway) with Christian formation and something also to do with the sense of community and common purpose fostered by Doug Henry, the Dean of the Honors College, and those support staff who work regularly with the students.

Self-portrait as I begin eight months of research leave

Self-portrait as I begin eight months of research leave

May 13, 2022

Your periodic reminder from Leszek Kołakowski: It’s possi...

Your periodic reminder from Leszek Kołakowski: It’s possible to be a conservative-liberal-socialist.

on resembling the Angel of History

Okay, so, first we have Andy Crouch’s book The Life We’re Looking For.

Then we have Brad East’s essay-review on Andy’s book in The New Atlantis.

Then we have three follow-up posts by Brad: one, two, and three.

Got all that? Trust me, it’s all worth reading. Okay, then let’s proceed. (Oh, also: I know both Andy and Brad so I will be using first names.)

Those follow-up posts concern Brad’s reservations about Andy’s book, but as he rightly points out, his review is a positive one, and we shouldn’t forget that. The reservations can be summed up in this passage from the review:

[Crouch’s] counsel is wise. But I worry that it understates the problem we face, particularly the extent to which it has infiltrated, and is already integrated with, each of our households. For Crouch agrees that the evils of Mammon and Digital and Acedia amount to something like a globalized conglomerate or racket. Before such an overwhelming power, how could my household be in a position to “choose a different vision,” even for its own members? We are too beholden to the economic and digital realities of modern life — too dependent on credit, too anxious about paying the rent, too distracted by Twitter, too reliant on Amazon, too deadened by Pornhub — to be in a position to opt for an alternative vision, much less to realize that one exists. We’ve got ends to meet. And at the end of the day, binging Netflix numbs the stress with far fewer consequences than opioids.

This is the burnout society, as Han calls it; or the Machine, in the label of Kingsnorth, who learned it from R. S. Thomas. We are sick. It would be unfair to fault Crouch for lacking the cure. The terrifying fact may be that there is none. Moreover, Crouch insists as a matter of principle that the life he commends to us is a life worth living for its own sake, not because it will Change The World. He is right about that. He is right as well to warn against the temptation to look for a magical elixir in the manner of the alchemist. That way lies danger: the quest for power to match the might of Mammon. As he writes, most people who want to influence the culture want to be a force, whereas “Jesus calls us to be a taste.” The book succeeds in offering us a taste, and it is unquestionably a taste of the good life. Whether that life is truly available to most of us, and how, is another matter.

My chief response to this is that I don’t read Andy’s book the way that Brad does, at least in the sense that I don’t see Andy making heroic demands upon us. There’s a point near the end of The Life We’re Looking For where Andy is talking about his use of his iPhone:

It would not be quite right to say that it is entirely up to me whether my iPhone, or future computational technology yet to be developed, becomes an instrument or a device – although it is true enough that every day I can choose which way to use it, within the limits of the programs and interfaces that others have designed it to provide.

But it is certainly true that in the long run that choice is up to us: what we ask our technology to do, what we ask its designers to optimize, what we believe is the good life that we are pursuing together.

That last sentence is the real key. I see the core purpose of Andy’s book to be not a denunciation of even a critique of technology but rather an attempt to orient us towards a vision of the kind of life that we want, individually and collectively, with the emphasis that if we really understand “the life we are looking for” we will be able to alter our technological environment, albeit in incremental ways. That doesn’t seem to me to require heroism; in fact, I would say that it’s pretty sober: our choices will not bring down the power of what Brad calls the Digital and what Andy (I think more accurately) calls Mammon – the Digital is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Mammon – but I think that those choices can create a subtle and over time significant redirection of our energies.

So I’m inclined to think that Brad’s question of whether “the good life … is truly available to most of us” is not the best one to ask. A better question – I think Andy pushes us towards this one, though maybe it’s just me who’s doing the pushing – is Augustinian in that it’s about orientation. Orientation is one of the most fundamental Augustinian concepts. He believed that caritas is “the motion of the soul towards God”; by contrast, cupiditas is the motion of the soul towards itself, which makes one incurvatus in se, curved in on oneself. For Augustine the initial question to be asked of anyone is: Which way are you facing? And I think what Andy is trying to do in his book is get people facing in the right direction – towards the life they really desire, as opposed to the life that Mammon wants to sell them – so that they may begin their pilgrimage, become true wayfarers. Wayfarers often have a long road ahead of them, but one of the best reasons to read Augustine, and to think along with that great saint, is to be reminded that what matters most is not the distance from our goal but whether we are facing it. Even if we never achieve “the good life” — in the Christian sense or even in a Stoic sense — surely we can today orient ourselves a little more accurately towards it than we did yesterday. (Maybe start by reading some Dickens?)

It’s true, as Brad suggests, that mighty Powers are arrayed against the wayfarer, such that we may end up looking more like Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History than Gandalf plodding towards the Shire; but better to be the Angel of History than one who strolls smilingly into Mammon’s glamorous emporium.

Paul Klee, Angelus Novus

Yann Kebbi’s drawings for the movie C’mon C’mon

May 12, 2022

nerves

Well, the North London Derby will be kicking off in a few minutes, and my nerves are tingling. I won’t be watching the match — I’m gonna practice meditation or something. But I have some thoughts.

I don’t expect Arsenal to win — Spurs are playing at home and they need the points more than Arsenal do — but that doesn’t mean anything because I never expect Arsenal to win. My son asks me before every Arsenal match how I think it’ll go, and I always explain, patiently and rationally, why they can’t possibly take all three points.

It may therefore come as no surprise that I would’ve been absolutely shocked at the beginning of the season — and even more after the first three matches of the season — to learn that the Gunners would be in the top four in May. But then everyone else would’ve been shocked also.

So, whatever happens from here on out, the lads have been great, and they deserve plaudits.

You might therefore expect that I am fully supportive of the decision to extend Arteta’s contract. In fact I am not —I am seriously doubtful about the decision. The achievements of this year are mainly due to the excellent construction of the squad, which has enabled a degree of success even in the face of many injuries. And that’s down to the front office. They’re the ones who deserve the same applause we give the players. (That said, with European football coming next season, they need to do some major reinforcement work in the offseason.)

Arteta, I think, has been the weak link. The problem is that he’s very poor at one aspect of the manager’s job: making in-game adjustments. He’s good at general strategy — though there he has a lot of help from the front office — and good at setting up his tactics for any given match. But when things go wrong (and in soccer you must expect that things will regularly go wrong) he seems befuddled. Several of Arsenal’s losses could have become wins if Arteta had acted more swiftly, decisively, and intelligently to make changes, whether in formation or personnel or both. But making the necessary adjustments just doesn’t seem to be in his skill set.

But I’m only doubtful that his contract should have been extended, not certain that it shouldn’t have. He may get better; and there aren’t many clearly superior candidates out there. (Though that Emery guy at Villarreal — he’s impressive! I wonder if he could be talked into moving to London….) And in any case the deal is done. But while I always worry about Arsenal, a good deal of that worry centers on whether Arteta will be able to handle the demands of a tough match. Arteta is my second-biggest concern; the first, as always, is whether Xhaka will decide that he needs to get himself sent off.

UPDATE: For “Xhaka” read “Holding.” Arteta’s complete inability to teach his players on-pitch discipline — very few of their many red cards in recent years have been undeserved — is another mark against him.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 529 followers