Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 115

May 19, 2022

The coming food catastrophe | The Economist:

By invading ...

The coming food catastrophe | The Economist:

By invading ukraine, Vladimir Putin will destroy the lives of people far from the battlefield — and on a scale even he may regret. The war is battering a global food system weakened by covid-19, climate change and an energy shock. Ukraine’s exports of grain and oilseeds have mostly stopped and Russia’s are threatened. Together, the two countries supply 12% of traded calories. Wheat prices, up 53% since the start of the year, jumped a further 6% on May 16th, after India said it would suspend exports because of an alarming heatwave.

The widely accepted idea of a cost-of-living crisis does not begin to capture the gravity of what may lie ahead. António Guterres, the un secretary general, warned on May 18th that the coming months threaten “the spectre of a global food shortage” that could last for years. The high cost of staple foods has already raised the number of people who cannot be sure of getting enough to eat by 440m, to 1.6bn. Nearly 250m are on the brink of famine. If, as is likely, the war drags on and supplies from Russia and Ukraine are limited, hundreds of millions more people could fall into poverty. Political unrest will spread, children will be stunted and people will starve.

Mr Putin must not use food as a weapon. Shortages are not the inevitable outcome of war. World leaders should see hunger as a global problem urgently requiring a global solution.

It’s hard to imagine anything more important for the world’s governments to focus on. I doubt that they will; I pray that they will.

Quanta Magazine interview with Leslie Lamport:

One last t...

Quanta Magazine interview with Leslie Lamport:

One last thing, about another side project of yours with a sizable impact: LaTeX. I’d like to finally clear something up with the creator. Is it pronounced LAH-tekh or LAY-tekh?

Any way you want. I don’t advise spending very much time thinking about it.

Kent Russell:

By accident of birth I am a modern, which m...

By accident of birth I am a modern, which means I will never know a charmed world. A world of consecrated hosts and faerie-haunted forests, where the line between individual agency and impersonal force is blurred at best. Gone is the idea of a porous human self, vulnerable to immaterial forces beyond his control. Significance has retreated from the outer world into our respective skulls, where, over time, it has stiffened, bloated, and finally decomposed into nothing, into dust.

This decay of faith — in institutions, in other people — is practically audible to me. I exist within a purely immanent culture in which the value of human life has been reduced to the parameters of the marketplace, where little is sacred and even less is profane. And I cannot take this shit much longer, I said.

So he started getting to know a man who says he can summon demons. An extraordinary essay. For context, I would — with all due humility — suggest that you read two pieces by me:

“Fantasy and the Buffered Self” “Something Happened By Us: A Demonology”May 18, 2022

I very much enjoyed the recent Rest Is History podcast ep...

I very much enjoyed the recent Rest Is History podcast episode on Agatha Christie — and if you did too, you might be interested in this essay of mine. I don’t think many people have ever read it, but it’s one I especially enjoyed writing, and the New Atlantis editors supplied some illuminating images. Give both the podcast and the essay a try, please!

The Incapable States of America? – Helen Dale:

State capa...

The Incapable States of America? – Helen Dale:

State capacity is a term drawn from economic history and development economics. It refers to a government’s ability to achieve policy goals in reference to specific aims, collect taxes, uphold law and order, and provide public goods. Its absence at the extremes is terrifying, and often used to illustrate things like “fragile states” or “failed states.” However, denoting calamitous governance in the developing world is not its only value. State capacity allows one to draw distinctions at varying levels of granularity between developed countries, and is especially salient when it comes to healthcare, policing, and immigration. It has a knock-on effect in the private sector, too, as business responds to government in administrative kind.

Think, for example, of Covid-19. The most reliable metric — if you wish to compare different countries’ responses to the pandemic — is excess deaths per 100,000 people over the relevant period. […]

The US has the worst excess death rate in the developed world (140 per 100,000). Australia has the best: -28 per 100,000. Yes, you read that right. Australia increased its life expectancy and general population health during the pandemic. So did Japan, albeit less dramatically. The rest of the developed world falls in between those two extremes: Italy and Germany are on 133 and 116 per 100,000 respectively, with the UK (109 per 100,000) doing a bit better. France and Sweden knocked it out of the park (63 and 56 per 100,000 excess deaths).

Dale’s takeaway: “Americans are individually charming and pleasant people who deploy their wits to get around a state that doesn’t work.”

pandemic and biopower

“Permanent Pandemic,” by Justin E. H. Smith:

When I say the regime, I do not mean the French government or the U.S. government or any particular government or organization. I mean the global order that has emerged over the past, say, fifteen years, for which COVID-19 served more as the great leap forward than as the revolution itself. The new regime is as much a technological regime as it is a pandemic regime. It has as much to do with apps and trackers, and governmental and corporate interests in controlling them, as it does with viruses and aerosols and nasal swabs. Fluids and microbes combined with touchscreens and lithium batteries to form a vast apparatus of control, which will almost certainly survive beyond the end date of any epidemiological rationale for the state of exception that began in early 2020.

The last great regime change happened after September 11, 2001, when terrorism and the pretext of its prevention began to reshape the contours of our public life. Of course, terrorism really does happen, yet the complex system of shoe removal, carry-on liquid rules, and all the other practices of twenty-first-century air travel long ago took on a reality of its own, sustaining itself quite apart from its efficacy in deterring attacks in the form of a massive jobs program for TSA agents and a gold mine of new entrepreneurial opportunities for vendors of travel-size toothpaste and antacids. The new regime might appropriately be imagined as an echo of the state of emergency that became permanent after 9/11, but now extended to the entirety of our social lives, rather than simply airports and other targets of potential terrorist interest.

An absolutely brilliant, disturbing, essential essay — to be considered in light of certain reflections by Giorgio Agamben. From later in the essay:

There is no question that changes of norms in Western countries since the beginning of the pandemic have given rise to a form of life plainly convergent with the Chinese model. Again, it might take more time to get there, and when we arrive, we might find that a subset of people are still enjoying themselves in a way they take to be an expression of freedom. But all this is spin, and what is occurring in both cases, the liberal-democratic and the overtly authoritarian alike, is the same: a transition to digitally and al- gorithmically calculated social credit, and the demise of most forms of community life outside the lens of the state and its corporate subcontractors.

I’m annotating this in detail — and by the by, there ought to be a better way for me to share my annotations. You can do some cool stuff with Hypothesis, but not all the things I want and need. Maybe more on those wants and needs in another post, but for now, back to my PDF of Smith’s terrific essay.

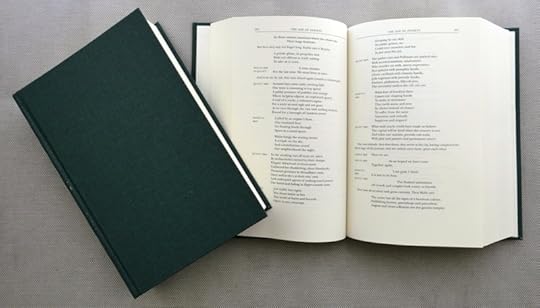

These beauties arrived: So now the set is complete: Had ...

These beauties arrived:

So now the set is complete:

Had to do my review from PDFs, so this seems my just reward.

May 17, 2022

Cory Doctorow:

Writing for a notional audience — particul...

Writing for a notional audience — particularly an audience of strangers — demands a comprehensive account that I rarely muster when I’m taking notes for myself. I am much better at kidding myself my ability to interpret my notes at a later date than I am at convincing myself that anyone else will be able to make heads or tails of them. […]

Blogging isn’t just a way to organize your research — it’s a way to do research for a book or essay or story or speech you don’t even know you want to write yet. It’s a way to discover what your future books and essays and stories and speeches will be about.

I like this post very much — and especially Doctorow’s idea of a blog as a place to make your commonplace book public. I hesitate to go all-in with this approach simply because I don’t want to overwhelm my readers with stuff.

I’m trying it out, but this is my fifth post today, which seems massively self-indulgent. On the other hand, it is rather odd for me to have two separate collections of notes, one on my computer and one on my blog.

notes

Interesting convo at micro.blog about what people use to take notes. Me?

Handwriting in notebooks (usually Leuchtturm) Marginal commentary and sticky notes in books Voice notes in .mp3 format (the plain text of audio) Plain text notes on the computerI want my notes to be future-proof and platform-agnostic.

For what it may be worth: As the years go by my opinion o...

For what it may be worth: As the years go by my opinion of OK Computer ascends and my opinion of Kid A descends.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 529 followers