Bryan Thomas Schmidt's Blog, page 52

April 10, 2011

Links of The Week Vol. 2 Issue 8

After a long delay, more helpful links:

http://blog.nathanbransford.com/2009/08/book-publishing-glossary.html -- Former agent Nathan Bransford offers a glossary of publishing lingo. Very helpful reference.

http://www.graspingforthewind.com/2011/04/07/sffwrtcht-a-chat-with-author-kristine-kathryn-rusch/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+GraspingForTheWind+%28Grasping+For+The+Win -- my interview with author Kristine Kathryn Rusch has a lot of good info for writers. First in a column I'll be doing weekly.

http://authorculture.blogspot.com/2011/04/how-to-offer-beneficial-critique.html -- How To Give a Beneficial Critique

http://www.kirkusreviews.com/blog/science-fiction-and-fantasy/sf-signal-how-start-reading-science-fiction-part-1/?fb_comment_id=fbc_10150149431281144_15894166_10150149648101144#f1390c056c -- SF Signal's John DeNardo offers a new series on how to start reading SF for novices.

http://www.newscientist.com/blogs/onepercent/2011/04/barcode-scanner-for-zebras.html -- Barcodes scanners for Zebras? Scientists develop a tool to identify unique animals by their stripes.

http://lifarre.com/socialnetwork/pg/blog/read/1181/my-unbreakable-heart-why-we-stay --- Author Kimberly Kincade's powerful essay about being in an abusive relationship

http://www.hbo.com/video/video.html?view=grid&vid=1170886&autoplay=true -- Awesome 15 minute preview of George R. R. Martin's "The Game Of Thrones" which comes to HBO next week.

http://blog.nathanbransford.com/2009/08/book-publishing-glossary.html -- Former agent Nathan Bransford offers a glossary of publishing lingo. Very helpful reference.

http://www.graspingforthewind.com/2011/04/07/sffwrtcht-a-chat-with-author-kristine-kathryn-rusch/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+GraspingForTheWind+%28Grasping+For+The+Win -- my interview with author Kristine Kathryn Rusch has a lot of good info for writers. First in a column I'll be doing weekly.

http://authorculture.blogspot.com/2011/04/how-to-offer-beneficial-critique.html -- How To Give a Beneficial Critique

http://www.kirkusreviews.com/blog/science-fiction-and-fantasy/sf-signal-how-start-reading-science-fiction-part-1/?fb_comment_id=fbc_10150149431281144_15894166_10150149648101144#f1390c056c -- SF Signal's John DeNardo offers a new series on how to start reading SF for novices.

http://www.newscientist.com/blogs/onepercent/2011/04/barcode-scanner-for-zebras.html -- Barcodes scanners for Zebras? Scientists develop a tool to identify unique animals by their stripes.

http://lifarre.com/socialnetwork/pg/blog/read/1181/my-unbreakable-heart-why-we-stay --- Author Kimberly Kincade's powerful essay about being in an abusive relationship

http://www.hbo.com/video/video.html?view=grid&vid=1170886&autoplay=true -- Awesome 15 minute preview of George R. R. Martin's "The Game Of Thrones" which comes to HBO next week.

Published on April 10, 2011 08:08

April 8, 2011

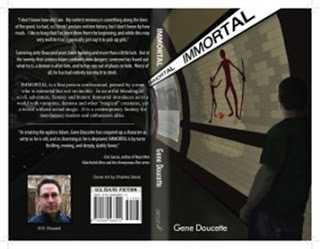

Immortal Blog Tour: Interview with Author Gene Doucette and an Excerpt From Immortal

My friend Gene Doucette has a new book out called Immortal. A combination of science fiction, fantasy, and horror, it's hard to categorize neatly by genre, but he's given me the opportunity to review the book and do an interview as well. As a bonus, you can find an excerpt below. I hope you'll check it out, [ Read More ]

Published on April 08, 2011 08:06

Immortal Blog Tour: Interview with Author Gene Doucette and an Excerpt From Immortal

My friend Gene Doucette has a new book out called Immortal. A combination of science fiction, fantasy, and horror, it's hard to categorize neatly by genre, but he's given me the opportunity to review the book and do an interview as well. As a bonus, you can find an excerpt below. I hope you'll check it out, and, if you like it, you can order the book here:

http://www.amazon.com/Immortal-ebook/dp/B004APA4ZW/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&m=AG56TWVU5XWC2&s=books&qid=1301763042&sr=1-1

Amazon.com says the following about Immortal:

I don't know how old I am. My earliest memory is something along the lines of fire good, ice bad, so I think I predate written history, but I don't know by how much. I like to brag that I've been there from the beginning, and while this may very well be true, I generally just say it to pick up girls.

Surviving sixty thousand years takes cunning and more than a little luck. But in the twenty-first century Adam confronts new dangers: someone has found out what he is, a demon is after him, and he has run out of places to hide. Worst of all, he has had entirely too much to drink.

IMMORTAL is a first person confessional, penned by a man who is immortal but not invincible. In an artful blending of sci-fi, adventure, fantasy and humour, Immortal introduces us to a world with vampires, demons and other magical creatures, yet a world without actual magic. It is a contemporary fantasy for non-fantasy readers and enthusiasts alike.

Here's my brief chat with Gene:

Immortality is a popular subject for a lot of writers. What made you decide to investigate it with Immortal?

To be honest, I had no idea how popular it was until I started promoting it. Then every few days it was, "Have you read…" or "Did you see…" I usually nod and try to point out where Immortal is different. And it is quite different. (I think the one story it has the most in common with is The Man From Earth, and the two stories are not at all close.)

I imagine I was drawn to it for the same reason most people were: the idea of being alive for long enough to have experienced things the rest of us have to read about is interesting. Maybe it's a fear of death manifesting itself creatively, I don't know.

In what way is Immortal different from the other stories?

When I began writing I posited one basic assumption: maybe this is all there is. I don't mean religiously (although it made sense for my main character Adam to be an atheist) so much as intellectually and socially. On the scale of Adam's lifetime societies are extremely temporary and knowledge is largely localized. There is a limit to the number of higher truths one can become aware of. In other words, grasping Plato doesn't change anything if you're still stuck in Aristotle's rational reality.

So there is no magic, or true gods, or unnamable higher powers. And Adam has not become so detached from the world that he's drifting through it like Bowie's character in The Man Who Fell To Earth. He experiences. He interacts. And he drinks too much. He is a living representation of the history of mankind, but that history is messy and violent and not particularly full of enlightenment.

But you've included vampires and demons in this world.

I did. And pixies and iffrits and dragons, and in the next book you'll see satyrs and werewolves and a few other things. But I took these beings and put them into a world without magic, and a world where history unfolds the way it has in the real world, in our world, meaning these creatures can't have been significant enough to have had a direct effect. These are beings on the margins.

Including extra-human creatures was a concession I found I had to make to tell the story. And I've found that as long as readers find Adam plausible—and so far they have—the beings he associates with occasionally are equally plausible.

One of Adam's themes throughout the book is that people exaggerate things, and that while some of the legendary things or events may have existed or happened, they were not as epic as described. It's not a leap to have your main character declare on one page that the French Revolution was just an after-the-fact rationalization of a street riot, and on another page point out that the proportion of vampires that are also evil killers is roughly the same as the proportion of humans that are also evil killers.

Is this book part of a series or a standalone?

It's part of a series now. When I first wrote it back in… good lord, 2004? I wrote a story that answered most of the questions raised within the book, such that a second or third book would have been less necessary, let's say. But in rewrites I realized I'd crammed far too much into the final portion of the novel and it was killing the pace. So I pulled out some things—the most significant being his history with a certain red-haired woman. And then I went and wrote a second book that still didn't answer those questions. So it's going to be at least three books long.

What other books have you written?

My other published work is in humor. In 1999 I put out a collection of my humor columns called Beating Up Daddy and in 2001 I released The Other Worst Case Scenario Survival Handbook: A Parody which is a collection of fake "chapters" I did on my old website for fun. I just released an anniversary edition of that with new chapters as an ebook. I also put out a second collection of humor columns called Vacations and Other Errors In Judgment as an ebook a year or so ago.

For novels, I wrote a book called Charlatan before Immortal. It was agented and shopped but didn't get published. I turned it into a screenplay a few years back, and that screenplay has won a few awards but isn't currently optioned. Which is a shame; I think it's better than most thrillers out there right now. And while Immortal was being shopped I wrote a novel called Fixer for which a deal may be pending. Then there's Hellenic Immortal, which is in process.

What made you decide to become a writer?

I don't think I ever made that decision. It was something I expected to be doing with my life as far back as when I learned how to read.

Do you outline, do character sketches, etc. or let the story unfold as it comes?

I start at the beginning and do the best I can to get to the end. So no outlines or character sketches or anything like that. But all that means is that I hold everything in my head rather than jotting it down. It's easier for me to make changes if it's not committed to "paper" somewhere. And my characters reveal themselves to me at the same time as the reader, usually through dialogue. It's not something I'd recommend to someone who isn't really good at writing dialogue, to be honest. (If I am allowed one moment of egotism: I am very good at dialogue.) Character delineation through conversation was one of the first things I learned how to do well, as a playwright.

Intrigued? I know I was. So here's an excerpt from Immortal chapter four, in which Adam ponders the nature of the only other immortal he's ever encountered, a red-haired mystery woman he's never spoken to and only seen in glimpses throughout history.

I ran through the possibilities again. Vampire was one that was most likely, as they are hypothetically just as immortal as me. Except I'd seen her in the daytime on more than one occasion. And, every vampire I ever met had black eyes. Possibly she was a vampire that didn't need to hide from sunlight and had blue eyes, but thats a bit like saying something is a cat except it walks on hind legs and has no fur or whiskers.I dont know any other sentient humanoids that have a get-out-of-death clause. Well other than me. And I don't have porcelain skin and haunting eyes. So she might be like me, but was she the same thing as me?

What was she?

Mind you, I'd run through all this before thousands of times. I've taken suggestions, too. A succubus I used to hang out with insisted my red-haired mystery girl was death incarnate, meaning my endless search for her was actually a complex working-out of my immortality issues. (A note: succubi are notorious amateur psychologists and have been since well before Freud. In fact I have it on good authority that Freud stole his whole gig from a particularly talkative succubus he used to know. And if you don't believe Freud knew a succubus, you haven't read Freud.) I didn't find the argument convincing. If I am to believe in some sort of anthropomorphic representation of mortality I should first develop a belief in some higher power, or at least in life-after-death.

I'm a pretty sad example of what one should do with eternal life. I've never reached any higher level of consciousness, I don't have access to any great truths, and I've never borne witness to the divine or transcendent. Some of this is just bad luck. Like working in the fishing industry in Galilee and never once running into Jesus. But in my defense there were an awful lot of people back then claiming to be the son of God; I probably wouldn't have been able to pick him out of the crowd. And since I don't believe there is a God, I doubt we would have gotten along all that well anyway.

I probably wasnt always quite so atheistic. I don't recall much of my early hunter-gatherer days, but I'm sure that back then I believed in lots of gods. And that the stars were pinholes in an enclosed firmament. There might even have been a giant turtle involved. And I distinctly recall a crude religious ceremony involving a mammoth skin and lots of face paint. But after centuries on the mortal coil I've come to realize that religion is for people who expect to die someday and really want to go to a better place when that happens. It doesn't apply to me.

Now be sure and check out the rest of the blog tour, offering new features every day: http://genedoucette.me/immortal-blog-tour-2011/

http://www.amazon.com/Immortal-ebook/dp/B004APA4ZW/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&m=AG56TWVU5XWC2&s=books&qid=1301763042&sr=1-1

Amazon.com says the following about Immortal:

I don't know how old I am. My earliest memory is something along the lines of fire good, ice bad, so I think I predate written history, but I don't know by how much. I like to brag that I've been there from the beginning, and while this may very well be true, I generally just say it to pick up girls.

Surviving sixty thousand years takes cunning and more than a little luck. But in the twenty-first century Adam confronts new dangers: someone has found out what he is, a demon is after him, and he has run out of places to hide. Worst of all, he has had entirely too much to drink.

IMMORTAL is a first person confessional, penned by a man who is immortal but not invincible. In an artful blending of sci-fi, adventure, fantasy and humour, Immortal introduces us to a world with vampires, demons and other magical creatures, yet a world without actual magic. It is a contemporary fantasy for non-fantasy readers and enthusiasts alike.

Here's my brief chat with Gene:

Immortality is a popular subject for a lot of writers. What made you decide to investigate it with Immortal?

To be honest, I had no idea how popular it was until I started promoting it. Then every few days it was, "Have you read…" or "Did you see…" I usually nod and try to point out where Immortal is different. And it is quite different. (I think the one story it has the most in common with is The Man From Earth, and the two stories are not at all close.)

I imagine I was drawn to it for the same reason most people were: the idea of being alive for long enough to have experienced things the rest of us have to read about is interesting. Maybe it's a fear of death manifesting itself creatively, I don't know.

In what way is Immortal different from the other stories?

When I began writing I posited one basic assumption: maybe this is all there is. I don't mean religiously (although it made sense for my main character Adam to be an atheist) so much as intellectually and socially. On the scale of Adam's lifetime societies are extremely temporary and knowledge is largely localized. There is a limit to the number of higher truths one can become aware of. In other words, grasping Plato doesn't change anything if you're still stuck in Aristotle's rational reality.

So there is no magic, or true gods, or unnamable higher powers. And Adam has not become so detached from the world that he's drifting through it like Bowie's character in The Man Who Fell To Earth. He experiences. He interacts. And he drinks too much. He is a living representation of the history of mankind, but that history is messy and violent and not particularly full of enlightenment.

But you've included vampires and demons in this world.

I did. And pixies and iffrits and dragons, and in the next book you'll see satyrs and werewolves and a few other things. But I took these beings and put them into a world without magic, and a world where history unfolds the way it has in the real world, in our world, meaning these creatures can't have been significant enough to have had a direct effect. These are beings on the margins.

Including extra-human creatures was a concession I found I had to make to tell the story. And I've found that as long as readers find Adam plausible—and so far they have—the beings he associates with occasionally are equally plausible.

One of Adam's themes throughout the book is that people exaggerate things, and that while some of the legendary things or events may have existed or happened, they were not as epic as described. It's not a leap to have your main character declare on one page that the French Revolution was just an after-the-fact rationalization of a street riot, and on another page point out that the proportion of vampires that are also evil killers is roughly the same as the proportion of humans that are also evil killers.

Is this book part of a series or a standalone?

It's part of a series now. When I first wrote it back in… good lord, 2004? I wrote a story that answered most of the questions raised within the book, such that a second or third book would have been less necessary, let's say. But in rewrites I realized I'd crammed far too much into the final portion of the novel and it was killing the pace. So I pulled out some things—the most significant being his history with a certain red-haired woman. And then I went and wrote a second book that still didn't answer those questions. So it's going to be at least three books long.

What other books have you written?

My other published work is in humor. In 1999 I put out a collection of my humor columns called Beating Up Daddy and in 2001 I released The Other Worst Case Scenario Survival Handbook: A Parody which is a collection of fake "chapters" I did on my old website for fun. I just released an anniversary edition of that with new chapters as an ebook. I also put out a second collection of humor columns called Vacations and Other Errors In Judgment as an ebook a year or so ago.

For novels, I wrote a book called Charlatan before Immortal. It was agented and shopped but didn't get published. I turned it into a screenplay a few years back, and that screenplay has won a few awards but isn't currently optioned. Which is a shame; I think it's better than most thrillers out there right now. And while Immortal was being shopped I wrote a novel called Fixer for which a deal may be pending. Then there's Hellenic Immortal, which is in process.

What made you decide to become a writer?

I don't think I ever made that decision. It was something I expected to be doing with my life as far back as when I learned how to read.

Do you outline, do character sketches, etc. or let the story unfold as it comes?

I start at the beginning and do the best I can to get to the end. So no outlines or character sketches or anything like that. But all that means is that I hold everything in my head rather than jotting it down. It's easier for me to make changes if it's not committed to "paper" somewhere. And my characters reveal themselves to me at the same time as the reader, usually through dialogue. It's not something I'd recommend to someone who isn't really good at writing dialogue, to be honest. (If I am allowed one moment of egotism: I am very good at dialogue.) Character delineation through conversation was one of the first things I learned how to do well, as a playwright.

Intrigued? I know I was. So here's an excerpt from Immortal chapter four, in which Adam ponders the nature of the only other immortal he's ever encountered, a red-haired mystery woman he's never spoken to and only seen in glimpses throughout history.

I ran through the possibilities again. Vampire was one that was most likely, as they are hypothetically just as immortal as me. Except I'd seen her in the daytime on more than one occasion. And, every vampire I ever met had black eyes. Possibly she was a vampire that didn't need to hide from sunlight and had blue eyes, but thats a bit like saying something is a cat except it walks on hind legs and has no fur or whiskers.I dont know any other sentient humanoids that have a get-out-of-death clause. Well other than me. And I don't have porcelain skin and haunting eyes. So she might be like me, but was she the same thing as me?

What was she?

Mind you, I'd run through all this before thousands of times. I've taken suggestions, too. A succubus I used to hang out with insisted my red-haired mystery girl was death incarnate, meaning my endless search for her was actually a complex working-out of my immortality issues. (A note: succubi are notorious amateur psychologists and have been since well before Freud. In fact I have it on good authority that Freud stole his whole gig from a particularly talkative succubus he used to know. And if you don't believe Freud knew a succubus, you haven't read Freud.) I didn't find the argument convincing. If I am to believe in some sort of anthropomorphic representation of mortality I should first develop a belief in some higher power, or at least in life-after-death.

I'm a pretty sad example of what one should do with eternal life. I've never reached any higher level of consciousness, I don't have access to any great truths, and I've never borne witness to the divine or transcendent. Some of this is just bad luck. Like working in the fishing industry in Galilee and never once running into Jesus. But in my defense there were an awful lot of people back then claiming to be the son of God; I probably wouldn't have been able to pick him out of the crowd. And since I don't believe there is a God, I doubt we would have gotten along all that well anyway.

I probably wasnt always quite so atheistic. I don't recall much of my early hunter-gatherer days, but I'm sure that back then I believed in lots of gods. And that the stars were pinholes in an enclosed firmament. There might even have been a giant turtle involved. And I distinctly recall a crude religious ceremony involving a mammoth skin and lots of face paint. But after centuries on the mortal coil I've come to realize that religion is for people who expect to die someday and really want to go to a better place when that happens. It doesn't apply to me.

Now be sure and check out the rest of the blog tour, offering new features every day: http://genedoucette.me/immortal-blog-tour-2011/

Published on April 08, 2011 08:06

April 6, 2011

Review: Star Wars-The Old Republic: Deceived by Paul S. Kemp

For me, Star Wars books are often like comfort food — familiar, not overly surprising, but good, an enjoyable way to pass the time. So when I scheduled Paul Kemp for my interview chat, I was surprised to learn his Star Wars books didn't include those familiar characters I'd grown to love–the characters who made [ Read More ]

Published on April 06, 2011 22:15

Review: Star Wars-The Old Republic: Deceived by Paul S. Kemp

For me, Star Wars books are often like comfort food -- familiar, not overly surprising, but good, an enjoyable way to pass the time. So when I scheduled Paul Kemp for my interview chat, I was surprised to learn his Star Wars books didn't include those familiar characters I'd grown to love--the characters who made me fall in love with science fiction, made me want to tell stories. But Paul Kemp wrote a Star Wars book (three now in fact), and we're close in age, so I wanted to commiserate. He must have viewed the saga at the same age I did with similar awe. What was it like to now be a part of that universe as a storyteller? So I ordered up some reading copies and read.

For me, Star Wars books are often like comfort food -- familiar, not overly surprising, but good, an enjoyable way to pass the time. So when I scheduled Paul Kemp for my interview chat, I was surprised to learn his Star Wars books didn't include those familiar characters I'd grown to love--the characters who made me fall in love with science fiction, made me want to tell stories. But Paul Kemp wrote a Star Wars book (three now in fact), and we're close in age, so I wanted to commiserate. He must have viewed the saga at the same age I did with similar awe. What was it like to now be a part of that universe as a storyteller? So I ordered up some reading copies and read.Imagine my surprise when I found myself engaged, even captivated by the characters. Kemp's ability to create immediate connections between characters and readers is admirable. He had me at "hello," you might say. And like a stalker, he never let me go, but in a good way. Even the antagonist, Darth Malgus is someone you can't help but feel sympathy for. He's relatable. He may be evil and dark and hateful, but he's human, just like the reader. And Kemp brings that out so well you almost root for him at times against the protagonists. That's great writing.

Like most Star Wars tie-ins the prose is kept simple, a few challenging words here and there, but not many. After all, these books are intended to be accessible for fans of all ages. And that requires talent, too. When the competition are sometimes books with extra effort at complex prose, to have written a book written simply but well which engages adults as well as children is a real accomplishment. One to be proud of.

I can't wait to chat with Paul and find out more about his writing journey, to soak up the lessons he has to teach us about writing, and to call him my friend. He tells me his assignment was to do a story with Darth Malgus, a character from the forthcoming online multi-player game "The Old Republic." He wrote a Malgus story with spades.

The book revolves around three central characters, the dark Sith Malgus, a rogue Jedi Aryn, and a pilot Zeerid. Malgus wants to conquer the universe for the Sith and rid them forever of the Jedi menace. Aryn wants revenge for the death of her mentor/father-figure at Malgus' hands. Zeerid, an old friend of Aryn's, is just trying to pay off a debt and provide artificial legs for his young daughter. Each of them gets sucked in by circumstance to a web of deception--both internal and external to themselves--and struggles to accomplish their goal. All of them wind up taking paths far different than they'd imagined in doing so. And all of them learn lessons that forever change them in the process.

Filled with action and moving at a steady clip, "Deceived" even includes a cute astromech droid character, who may remind us of ancestors to come. It has romance, betrayal, political intrigue, and rivalry. It's a well told tale that could be set in any universe but works exceedingly well in the confines of the familiar Star Wars one. Truly these are characters worth discovering and enjoying. I'd like to see more of each of them.

I can't wait to read more from Kemp. Highly recommended.

Published on April 06, 2011 22:15

April 3, 2011

Immortal Blog Tour: Interview with Author Gene Doucette and an Excerpt From Immortal

My friend Gene Doucette has a new book out called Immortal. A combination of science fiction, fantasy, and horror, it's hard to categorize neatly by genre, but he's given me the opportunity to review the book and do an interview as well. As a bonus, you can find an excerpt below. I hope you'll check it out, and, if you like it, you can order the book here:

http://www.amazon.com/Immortal-ebook/dp/B004APA4ZW/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&m=AG56TWVU5XWC2&s=books&qid=1301763042&sr=1-1

Amazon.com says the following about Immortal:

I don't know how old I am. My earliest memory is something along the lines of fire good, ice bad, so I think I predate written history, but I don't know by how much. I like to brag that I've been there from the beginning, and while this may very well be true, I generally just say it to pick up girls.

Surviving sixty thousand years takes cunning and more than a little luck. But in the twenty-first century Adam confronts new dangers: someone has found out what he is, a demon is after him, and he has run out of places to hide. Worst of all, he has had entirely too much to drink.

IMMORTAL is a first person confessional, penned by a man who is immortal but not invincible. In an artful blending of sci-fi, adventure, fantasy and humour, Immortal introduces us to a world with vampires, demons and other magical creatures, yet a world without actual magic. It is a contemporary fantasy for non-fantasy readers and enthusiasts alike.

Here's my brief chat with Gene:

Immortality is a popular subject for a lot of writers. What made you decide to investigate it with Immortal?

To be honest, I had no idea how popular it was until I started promoting it. Then every few days it was, "Have you read…" or "Did you see…" I usually nod and try to point out where Immortal is different. And it is quite different. (I think the one story it has the most in common with is The Man From Earth, and the two stories are not at all close.)

I imagine I was drawn to it for the same reason most people were: the idea of being alive for long enough to have experienced things the rest of us have to read about is interesting. Maybe it's a fear of death manifesting itself creatively, I don't know.

In what way is Immortal different from the other stories?

When I began writing I posited one basic assumption: maybe this is all there is. I don't mean religiously (although it made sense for my main character Adam to be an atheist) so much as intellectually and socially. On the scale of Adam's lifetime societies are extremely temporary and knowledge is largely localized. There is a limit to the number of higher truths one can become aware of. In other words, grasping Plato doesn't change anything if you're still stuck in Aristotle's rational reality.

So there is no magic, or true gods, or unnamable higher powers. And Adam has not become so detached from the world that he's drifting through it like Bowie's character in The Man Who Fell To Earth. He experiences. He interacts. And he drinks too much. He is a living representation of the history of mankind, but that history is messy and violent and not particularly full of enlightenment.

But you've included vampires and demons in this world.

I did. And pixies and iffrits and dragons, and in the next book you'll see satyrs and werewolves and a few other things. But I took these beings and put them into a world without magic, and a world where history unfolds the way it has in the real world, in our world, meaning these creatures can't have been significant enough to have had a direct effect. These are beings on the margins.

Including extra-human creatures was a concession I found I had to make to tell the story. And I've found that as long as readers find Adam plausible—and so far they have—the beings he associates with occasionally are equally plausible.

One of Adam's themes throughout the book is that people exaggerate things, and that while some of the legendary things or events may have existed or happened, they were not as epic as described. It's not a leap to have your main character declare on one page that the French Revolution was just an after-the-fact rationalization of a street riot, and on another page point out that the proportion of vampires that are also evil killers is roughly the same as the proportion of humans that are also evil killers.

Is this book part of a series or a standalone?

It's part of a series now. When I first wrote it back in… good lord, 2004? I wrote a story that answered most of the questions raised within the book, such that a second or third book would have been less necessary, let's say. But in rewrites I realized I'd crammed far too much into the final portion of the novel and it was killing the pace. So I pulled out some things—the most significant being his history with a certain red-haired woman. And then I went and wrote a second book that still didn't answer those questions. So it's going to be at least three books long.

What other books have you written?

My other published work is in humor. In 1999 I put out a collection of my humor columns called Beating Up Daddy and in 2001 I released The Other Worst Case Scenario Survival Handbook: A Parody which is a collection of fake "chapters" I did on my old website for fun. I just released an anniversary edition of that with new chapters as an ebook. I also put out a second collection of humor columns called Vacations and Other Errors In Judgment as an ebook a year or so ago.

For novels, I wrote a book called Charlatan before Immortal. It was agented and shopped but didn't get published. I turned it into a screenplay a few years back, and that screenplay has won a few awards but isn't currently optioned. Which is a shame; I think it's better than most thrillers out there right now. And while Immortal was being shopped I wrote a novel called Fixer for which a deal may be pending. Then there's Hellenic Immortal, which is in process.

What made you decide to become a writer?

I don't think I ever made that decision. It was something I expected to be doing with my life as far back as when I learned how to read.

Do you outline, do character sketches, etc. or let the story unfold as it comes?

I start at the beginning and do the best I can to get to the end. So no outlines or character sketches or anything like that. But all that means is that I hold everything in my head rather than jotting it down. It's easier for me to make changes if it's not committed to "paper" somewhere. And my characters reveal themselves to me at the same time as the reader, usually through dialogue. It's not something I'd recommend to someone who isn't really good at writing dialogue, to be honest. (If I am allowed one moment of egotism: I am very good at dialogue.) Character delineation through conversation was one of the first things I learned how to do well, as a playwright.

Intrigued? I know I was. So here's an excerpt from Immortal chapter four, in which Adam ponders the nature of the only other immortal he's ever encountered, a red-haired mystery woman he's never spoken to and only seen in glimpses throughout history.

I ran through the possibilities again. Vampire was one that was most likely, as they are hypothetically just as immortal as me. Except I'd seen her in the daytime on more than one occasion. And, every vampire I ever met had black eyes. Possibly she was a vampire that didn't need to hide from sunlight and had blue eyes, but thats a bit like saying something is a cat except it walks on hind legs and has no fur or whiskers.

I dont know any other sentient humanoids that have a get-out-of-death clause. Well other than me. And I don't have porcelain skin and haunting eyes. So she might be like me, but was she the same thing as me?

What was she?

Mind you, I'd run through all this before thousands of times. I've taken suggestions, too. A succubus I used to hang out with insisted my red-haired mystery girl was death incarnate, meaning my endless search for her was actually a complex working-out of my immortality issues. (A note: succubi are notorious amateur psychologists and have been since well before Freud. In fact I have it on good authority that Freud stole his whole gig from a particularly talkative succubus he used to know. And if you don't believe Freud knew a succubus, you haven't read Freud.) I didn't find the argument convincing. If I am to believe in some sort of anthropomorphic representation of mortality I should first develop a belief in some higher power, or at least in life-after-death.

I'm a pretty sad example of what one should do with eternal life. I've never reached any higher level of consciousness, I don't have access to any great truths, and I've never borne witness to the divine or transcendent. Some of this is just bad luck. Like working in the fishing industry in Galilee and never once running into Jesus. But in my defense there were an awful lot of people back then claiming to be the son of God; I probably wouldn't have been able to pick him out of the crowd. And since I don't believe there is a God, I doubt we would have gotten along all that well anyway.

I probably wasnt always quite so atheistic. I don't recall much of my early hunter-gatherer days, but I'm sure that back then I believed in lots of gods. And that the stars were pinholes in an enclosed firmament. There might even have been a giant turtle involved. And I distinctly recall a crude religious ceremony involving a mammoth skin and lots of face paint. But after centuries on the mortal coil I've come to realize that religion is for people who expect to die someday and really want to go to a better place when that happens. It doesn't apply to me.

http://www.amazon.com/Immortal-ebook/dp/B004APA4ZW/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&m=AG56TWVU5XWC2&s=books&qid=1301763042&sr=1-1

Amazon.com says the following about Immortal:

I don't know how old I am. My earliest memory is something along the lines of fire good, ice bad, so I think I predate written history, but I don't know by how much. I like to brag that I've been there from the beginning, and while this may very well be true, I generally just say it to pick up girls.

Surviving sixty thousand years takes cunning and more than a little luck. But in the twenty-first century Adam confronts new dangers: someone has found out what he is, a demon is after him, and he has run out of places to hide. Worst of all, he has had entirely too much to drink.

IMMORTAL is a first person confessional, penned by a man who is immortal but not invincible. In an artful blending of sci-fi, adventure, fantasy and humour, Immortal introduces us to a world with vampires, demons and other magical creatures, yet a world without actual magic. It is a contemporary fantasy for non-fantasy readers and enthusiasts alike.

Here's my brief chat with Gene:

Immortality is a popular subject for a lot of writers. What made you decide to investigate it with Immortal?

To be honest, I had no idea how popular it was until I started promoting it. Then every few days it was, "Have you read…" or "Did you see…" I usually nod and try to point out where Immortal is different. And it is quite different. (I think the one story it has the most in common with is The Man From Earth, and the two stories are not at all close.)

I imagine I was drawn to it for the same reason most people were: the idea of being alive for long enough to have experienced things the rest of us have to read about is interesting. Maybe it's a fear of death manifesting itself creatively, I don't know.

In what way is Immortal different from the other stories?

When I began writing I posited one basic assumption: maybe this is all there is. I don't mean religiously (although it made sense for my main character Adam to be an atheist) so much as intellectually and socially. On the scale of Adam's lifetime societies are extremely temporary and knowledge is largely localized. There is a limit to the number of higher truths one can become aware of. In other words, grasping Plato doesn't change anything if you're still stuck in Aristotle's rational reality.

So there is no magic, or true gods, or unnamable higher powers. And Adam has not become so detached from the world that he's drifting through it like Bowie's character in The Man Who Fell To Earth. He experiences. He interacts. And he drinks too much. He is a living representation of the history of mankind, but that history is messy and violent and not particularly full of enlightenment.

But you've included vampires and demons in this world.

I did. And pixies and iffrits and dragons, and in the next book you'll see satyrs and werewolves and a few other things. But I took these beings and put them into a world without magic, and a world where history unfolds the way it has in the real world, in our world, meaning these creatures can't have been significant enough to have had a direct effect. These are beings on the margins.

Including extra-human creatures was a concession I found I had to make to tell the story. And I've found that as long as readers find Adam plausible—and so far they have—the beings he associates with occasionally are equally plausible.

One of Adam's themes throughout the book is that people exaggerate things, and that while some of the legendary things or events may have existed or happened, they were not as epic as described. It's not a leap to have your main character declare on one page that the French Revolution was just an after-the-fact rationalization of a street riot, and on another page point out that the proportion of vampires that are also evil killers is roughly the same as the proportion of humans that are also evil killers.

Is this book part of a series or a standalone?

It's part of a series now. When I first wrote it back in… good lord, 2004? I wrote a story that answered most of the questions raised within the book, such that a second or third book would have been less necessary, let's say. But in rewrites I realized I'd crammed far too much into the final portion of the novel and it was killing the pace. So I pulled out some things—the most significant being his history with a certain red-haired woman. And then I went and wrote a second book that still didn't answer those questions. So it's going to be at least three books long.

What other books have you written?

My other published work is in humor. In 1999 I put out a collection of my humor columns called Beating Up Daddy and in 2001 I released The Other Worst Case Scenario Survival Handbook: A Parody which is a collection of fake "chapters" I did on my old website for fun. I just released an anniversary edition of that with new chapters as an ebook. I also put out a second collection of humor columns called Vacations and Other Errors In Judgment as an ebook a year or so ago.

For novels, I wrote a book called Charlatan before Immortal. It was agented and shopped but didn't get published. I turned it into a screenplay a few years back, and that screenplay has won a few awards but isn't currently optioned. Which is a shame; I think it's better than most thrillers out there right now. And while Immortal was being shopped I wrote a novel called Fixer for which a deal may be pending. Then there's Hellenic Immortal, which is in process.

What made you decide to become a writer?

I don't think I ever made that decision. It was something I expected to be doing with my life as far back as when I learned how to read.

Do you outline, do character sketches, etc. or let the story unfold as it comes?

I start at the beginning and do the best I can to get to the end. So no outlines or character sketches or anything like that. But all that means is that I hold everything in my head rather than jotting it down. It's easier for me to make changes if it's not committed to "paper" somewhere. And my characters reveal themselves to me at the same time as the reader, usually through dialogue. It's not something I'd recommend to someone who isn't really good at writing dialogue, to be honest. (If I am allowed one moment of egotism: I am very good at dialogue.) Character delineation through conversation was one of the first things I learned how to do well, as a playwright.

Intrigued? I know I was. So here's an excerpt from Immortal chapter four, in which Adam ponders the nature of the only other immortal he's ever encountered, a red-haired mystery woman he's never spoken to and only seen in glimpses throughout history.

I ran through the possibilities again. Vampire was one that was most likely, as they are hypothetically just as immortal as me. Except I'd seen her in the daytime on more than one occasion. And, every vampire I ever met had black eyes. Possibly she was a vampire that didn't need to hide from sunlight and had blue eyes, but thats a bit like saying something is a cat except it walks on hind legs and has no fur or whiskers.

I dont know any other sentient humanoids that have a get-out-of-death clause. Well other than me. And I don't have porcelain skin and haunting eyes. So she might be like me, but was she the same thing as me?

What was she?

Mind you, I'd run through all this before thousands of times. I've taken suggestions, too. A succubus I used to hang out with insisted my red-haired mystery girl was death incarnate, meaning my endless search for her was actually a complex working-out of my immortality issues. (A note: succubi are notorious amateur psychologists and have been since well before Freud. In fact I have it on good authority that Freud stole his whole gig from a particularly talkative succubus he used to know. And if you don't believe Freud knew a succubus, you haven't read Freud.) I didn't find the argument convincing. If I am to believe in some sort of anthropomorphic representation of mortality I should first develop a belief in some higher power, or at least in life-after-death.

I'm a pretty sad example of what one should do with eternal life. I've never reached any higher level of consciousness, I don't have access to any great truths, and I've never borne witness to the divine or transcendent. Some of this is just bad luck. Like working in the fishing industry in Galilee and never once running into Jesus. But in my defense there were an awful lot of people back then claiming to be the son of God; I probably wouldn't have been able to pick him out of the crowd. And since I don't believe there is a God, I doubt we would have gotten along all that well anyway.

I probably wasnt always quite so atheistic. I don't recall much of my early hunter-gatherer days, but I'm sure that back then I believed in lots of gods. And that the stars were pinholes in an enclosed firmament. There might even have been a giant turtle involved. And I distinctly recall a crude religious ceremony involving a mammoth skin and lots of face paint. But after centuries on the mortal coil I've come to realize that religion is for people who expect to die someday and really want to go to a better place when that happens. It doesn't apply to me.

Published on April 03, 2011 08:56

April 2, 2011

Guest Post: Defining Sword & Sorcery

Although it isn't original to this site, I can't resist reposting this article from www.howardandrewjones.com last December. Howard, one of the editors of Black Gate, is a talented author and somewhat of an authority on historical fantasy. His insights are well worth reading.

by Howard Andrew JonesSome years back I decided that if I was serious about writing fantasy I'd best understand the roots of the genre, and I threw myself into reading work by its founding fathers and mothers. I came away with a deep appreciation of a number of authors I'd never explored in much detail before (Robert E. Howard, Lord Dunsany, Clark Asthon Smith, Poul Anderson, C.L. Moore, and others) and a better understanding of the kind of fantasy I most enjoyed. Some call it heroic fiction, and others have tried other labels, but the one that seems to have stuck the most is sword-and-sorcery, a term coined by Fritz Leiber. While I think I know it when I see it, a lot of different people have attempted to define it. Back when I helmed the Flashing Swords e-zine I had to tell the readers exactly what kind of fiction I most wanted to print, and so I set out to describe what I thougth sword-and-sorcery was all about. That's been a few years ago, and the definitions have since been improved upon with some suggestions from John Hocking, William King, Robert Rhodes, and John "The Gneech" Robey.The Environment: Sword-and-sorcery fiction takes place in lands different from our own, where technology is relatively primitive, allowing the protagonists to overcome their martial obstacles face-to-face. Magic works, but seldom at the behest of the heroes. More often sorcery is just one more obstacle used against them and is usually wielded by villains or monsters. The landscape is exotic; either a different world, or far corners of our own.The Protagonists: The heroes live by their cunning or brawn, frequently both. They are usually strangers or outcasts, rebels imposing their own justice on the wilds or the strange and decadent civilizations which they encounter. They are usually commoners or barbarians; should they hail from the higher ranks of society then they are discredited, disinherited, or come from the lower ranks of nobility (the lowest of the high).Obstacles: Sword-and-sorcery's protagonists must best fantastic dangers, monstrous horrors, and dark sorcery to earn riches, astonishing treasure, the love of dazzling members of the opposite sex, or the right to live another day.Structure: Sword-and-sorcery is usually crafted with traditional structure. Stream-of-consciousness, slice-of-life, or any sort of experimental narrative effects, when they appear, are methods used to advance the plot, rather than ends in themselves. A tale of sword-and-sorcery has a beginning, middle, and end; a problem and solution; a climax and resolution. Most important of all, sword-and-sorcery moves at a headlong pace and overflows with action and thrilling adventure.The protagonists in sword-and-sorcery fiction are most often thieves, mercenaries, or barbarians struggling not for worlds or kingdoms, but for their own gain or mere survival. They are rebels against authority, skeptical of civilization and its rulers and adherents. While the strengths and skills of sword-and-sorcery heroes are romanticized, their exploits take place on a very different stage from one where lovely princesses, dashing nobles, and prophesied saviors are cast as the leads. Sword-and-sorcery heroes face more immediate problems than those of questing kings. They are cousins of the lone gunslingers of American westerns and the wandering samurai of Japanese folklore, traveling through the wilderness to right wrongs or simply to earn food, shelter, and coin. Unknown or hazardous lands are an essential ingredient of the genre, and if its protagonists should chance upon inhabited lands, they are often strangers to either the culture or civilization itself.Sword-and-sorcery distances itself further from high or epic fantasy by adopting a gritty, realistic tone that creates an intense, often grim, sense of realism seemingly at odds with a fantasy setting. This vein of hardboiled realism casts the genre's fantastic elements in an entirely new light, while rendering characters and conflict in a much more immediate fashion. Sword-and-sorcery at times veers into dark, fatalistic territory reminiscent of the grimmer examples of noir-crime fiction. This takes the fantasy genre, the most popular examples of which might be characterized as bucolic fairy tales with pre-ordained happy endings, and transposes a bleak, essentially urban style upon it with often startling effect.While sword-and-sorcery is a relative to high fantasy, it is a different animal. High fantasy, mostly invented by William Morris as an echo of Sir Thomas Mallory and then popularized by J.R.R. Tolkien, moves for the most part at a slow, stately, pace, meandering gently from plot point to plot point, or, as is often the case, from location to location. Movie critic Roger Ebert has some astute observations on The Lord of the Rings, which I will quote here. "The trilogy is mostly about leaving places, going places, being places, and going on to other places, all amid fearful portents and speculations. There are a great many mountains, valleys, streams, villages, caves, residences, grottos, bowers, fields, high roads, low roads, and along them the Hobbits and their larger companions travel while paying great attention to mealtimes. Landscapes are described with the faithful detail of a Victorian travel writer. … mostly the trilogy is an unfolding, a quest, a journey, told in an elevated, archaic, romantic prose style that tests our capacity for the declarative voice." While exotic landscape is present, even common, in sword-and-sorcery, it is displayed differently and toward a different effect. Sword-and-sorcery was birthed in an entirely different tradition. Robert E. Howard, its creator, wrote for the pulps. The pulp magazines, the television of their day, were fueled by quick moving action. The stories needed to grab you within the first few sentences so that if you were browsing the magazine at the news stand you'd feel compelled to purchase it to finish. The pulp stories were meant to seize your attention from the opening lines and never let go. This difference in pacing is crucial and there are hidden difficulties attendant in trying to create it on the page. My friend, the mighty John Chris Hocking, added this to the discussion: "Some sword-and-sorcery authors seem to believe that swift pacing must equal Action. And that Action must equal Violence. Neither of these things are true. All the fighting and running and frenzy you create will grow tiresome unless it is moving the story forward. Sure, Action is great unto itself, but it is the unfolding of the plot that truly captivates."The best way to acquaint oneself with this style of pacing is to READ the writers who did it. Certainly this is a far from exhaustive list, but this is a good start to the process. Read for enjoyment (if you're not reading for enjoyment you probably shouldn't bother trying to write in the style) but read critically as well. There are other fabulous works and fabulous authors, but this small selection cited here gives you a basic primer on sword-and-sorcery focusing mostly on shorter stories, short novels, and novellas. It is meant as an immersive introduction that will not take two or three years of study. Once you have the material in hand it would not take long to familiarize yourself with it.Robert E. Howard: There's a recent set of Howard books from Del Rey that collect all the Conan tales. Find a copy of The Coming of Conan and dip into the collection. At the least, read "Tower of the Elephant," "Queen of the Black Coast," and "Rogues in the House." Fritz Leiber: Leiber's famed Lankhmar stories have been reprinted so many times that it's hard to suggest any particular volume because the contents vary. Instead here are specific stories. Read three or four of any of these: "Thieves' House," "The Jewels in the Forest," "The Sunken Land," "The Howling Tower," "The Seven Black Priests," "Claws from the Night," "Bazaar of the Bizarre," "Lean Times in Lankhmar," "The Lords of Quarmall." Jack Vance: The Dying Earth – sword-and-sorcery, science fiction, planetary romance—whatever it is exactly that Vance wrote when he bent so many genres (long before that was in vogue) he wrote it well, with amazing world building and vivid imagination. Don't feel compelled to read the entire series, just the first short little novel.Michael Moorcock: The first Elric novel or the first Hawkmoon novel.Leigh Brackett: Beg, borrow, or steal the Sea Kings of Mars aka The Sword of Rhiannon. Sure, it's really sword-and-planet, but sword-and-planet is really just sword-and-sorcery with a science fiction veneer. And Leigh Brackett was one of the very, very best sword-and-planet writers.M.John Harrison: The Pastel City.What to look for when you're reading?First and foremost notice the pacing.Notice the tone in Howard, the somber, headlong drive.Notice how dialogue is used to reveal the character rather than to reveal plot points and backstory. Pay attention to how the characters sparkle this way particularly in Leiber and Harrison. Notice Howard's skill with Conan. He is far more than the stereotype suggested by his detractors, and more complex than barbarians crafted by most of his imitators.Notice how atmosphere permeates everything in Brackett and Harrison and Vance—study their world building, and the sense of wonder they constantly evoke. One thing you should note is that none of these authors worked from templates. The character classes as typified by role-playing games like Dungeons and Dragons were designed based on the works of these authors so that players might create characters like those from their favorite fantasy stories. Now many of those templates and settings have become rigid and unchanging. Castle, wizard with spell book, dragon, orc, halfing, thieves' guild (from Leiber), chaos, law (from Moorcock). Too many of us have forgotten the source material. Those templates need to be set aside. If you're writing for a game company by all means use elves, hobbits, ogres and the like, but otherwise leave them in their castles and invent something of your own. If you do want to write of elves or ogres, then you'll need to do something unique with them.

Published on April 02, 2011 19:57

March 29, 2011

The Importance of Preparedness In Event of Family Crisis

Okay, this is a departure from the usual focus of this blog. But most of you know I have been going through a huge crisis with my wife, Bianca. Bianca has Bipolar Disorder I, a serious mental illness which involves manic episodes in which she is very aggressive and angry and hard to control. Bianca hates lack of control anyway. I sometimes wonder if this is because her mind races out of control even when she's stable and so she constantly grasps for control to fight her sense of losing control. I don't know. I can't be inside the mind of a Bipolar person. But I know that if I had ever imagined how bad a crisis could be, I would have been more prepared.

When Bianca is having a manic episode, she can seem normal to people who don't know her. Sure, she talks a lot, but Bianca loves to talk even when she isn't manic. And she can definitely exercise her will and free choice. The problem is, she is not rational and her choices are wrong and not in her best interest or even crazy illogical. But because of the stupidly written HIPPA law given us by Nancy Landon Kassebaum and Ted Kennedy, hospitals must protect patient privacy and that means, since the law is so broad, they tend to obey patient's wishes until they are declared mentally competent by a court of law. So Bianca was able to shut me out of any health info, any visits, any decisions. She could order up medical tests which cost tons of money by claiming cancer or other ills. I don't think she did but she could have. And I would have a bill to pay with no input on the decision.

What Bianca and I needed is what all of you with spouses need: executed power of attorney and medical power of attorney documents (also called designated health care agent). These documents, fairly standard, can be prepared for you by an attorney at low cost, signed before a notary, and then ready if you need them. Dear God, I hope you never do, but what if you did. What if one of you became brain damaged and was in dementia, making insane decisions but not able to be declared mentally unsound easily. What would the other person do? Want to feel helpless? Wait for that to happen. What if one of you was in a coma and the other needed to make decisions on co-signed finances or finances you didn't know much about? About medical treatment, etc.?

If you don't have those documents, you will have to file for guardianship like I did and it will cost you 20 times more money and stress. Don't wait to find out, be prepared.

On top of it, if one of you handles all the bank accounts and stocks, etc., create a one sheet with passwords, account numbers, bank addresses, even phone numbers and contact persons for the other. Put it in a safety deposit box but let the other person and one friend you trust know it's there. The person you love may be so distraught they won't remember. The friend can remind them.

Here's an example of the document as it is statutory in Texas: http://www.ilrg.com/forms/states/tx-powerofattorneymed.html

In most cases, you will want to assign two designees with health care power of attorney. That's in case both of you are incapacitated at the same time in an accident, so someone can pay bills, take of the kids and pets, etc. Don't be afraid. The documents will specify the circumstances under which they can be used, and the length of time before the power is resumed by you. In case of divorce, the document can be listed as being nullified. It's not giving up your rights immediately at any time. It's for emergencies only. And it's worth it.

Trust me. You don't want to live the nightmare I am living. I hope to God you never face similar circumstances, but what if you do? It's hard enough seeing the person you love in this condition. Having them fighting your every decision when you're trying to just get them the best care. It's hard enough having a hospital treat you like a stranger with no say. Do you really want that? Being prepared is the only way to avoid the stress and bankrupting expense I am facing. And you'll be able to act quickly, not wait for court decisions. It may be the difference between life and death for your loved one. In my case, it's not, thank God. But what if it was? Can any of us afford to take that chance?

For what it's worth...

When Bianca is having a manic episode, she can seem normal to people who don't know her. Sure, she talks a lot, but Bianca loves to talk even when she isn't manic. And she can definitely exercise her will and free choice. The problem is, she is not rational and her choices are wrong and not in her best interest or even crazy illogical. But because of the stupidly written HIPPA law given us by Nancy Landon Kassebaum and Ted Kennedy, hospitals must protect patient privacy and that means, since the law is so broad, they tend to obey patient's wishes until they are declared mentally competent by a court of law. So Bianca was able to shut me out of any health info, any visits, any decisions. She could order up medical tests which cost tons of money by claiming cancer or other ills. I don't think she did but she could have. And I would have a bill to pay with no input on the decision.

What Bianca and I needed is what all of you with spouses need: executed power of attorney and medical power of attorney documents (also called designated health care agent). These documents, fairly standard, can be prepared for you by an attorney at low cost, signed before a notary, and then ready if you need them. Dear God, I hope you never do, but what if you did. What if one of you became brain damaged and was in dementia, making insane decisions but not able to be declared mentally unsound easily. What would the other person do? Want to feel helpless? Wait for that to happen. What if one of you was in a coma and the other needed to make decisions on co-signed finances or finances you didn't know much about? About medical treatment, etc.?

If you don't have those documents, you will have to file for guardianship like I did and it will cost you 20 times more money and stress. Don't wait to find out, be prepared.

On top of it, if one of you handles all the bank accounts and stocks, etc., create a one sheet with passwords, account numbers, bank addresses, even phone numbers and contact persons for the other. Put it in a safety deposit box but let the other person and one friend you trust know it's there. The person you love may be so distraught they won't remember. The friend can remind them.

Here's an example of the document as it is statutory in Texas: http://www.ilrg.com/forms/states/tx-powerofattorneymed.html

In most cases, you will want to assign two designees with health care power of attorney. That's in case both of you are incapacitated at the same time in an accident, so someone can pay bills, take of the kids and pets, etc. Don't be afraid. The documents will specify the circumstances under which they can be used, and the length of time before the power is resumed by you. In case of divorce, the document can be listed as being nullified. It's not giving up your rights immediately at any time. It's for emergencies only. And it's worth it.

Trust me. You don't want to live the nightmare I am living. I hope to God you never face similar circumstances, but what if you do? It's hard enough seeing the person you love in this condition. Having them fighting your every decision when you're trying to just get them the best care. It's hard enough having a hospital treat you like a stranger with no say. Do you really want that? Being prepared is the only way to avoid the stress and bankrupting expense I am facing. And you'll be able to act quickly, not wait for court decisions. It may be the difference between life and death for your loved one. In my case, it's not, thank God. But what if it was? Can any of us afford to take that chance?

For what it's worth...

Published on March 29, 2011 20:29

March 28, 2011

Space Opera: The Junction Between Worlds

Guest Post by John H. Ginsberg-Stevens

"But there was little sense, in criticism and reviewing of the fifties, of 'space opera' meaning anything other then 'hacky, grinding, stinking, outworn' SF stories of any kind" - Kathryn Cramer & David G. Hartwell, The Space Opera Renaissance (pp.11-12).

"Space Opera" always sounds so majestic when you first hear the term used. It conjures up a Wagnerian aesthetic, a vast, significant drama about to unfold. It evokes a grand canvas of interstellar wonders, of great empires and uncountable fleets clashing for the greatest prize: the galaxy itself! And then, you go to WIkipedia:

"Space opera is a subgenre of speculative fiction that emphasizes romantic, often melodramatic adventure, set mainly or entirely in outer space, generally involving conflict between opponents possessing advanced technologies and abilities. The name has no relation to music; it is analogous to soap operas . . . . "- Wikipedia entry for "Space Opera."

Well, heck. Space opera, while sometimes a magnificent, even ostentatious form of SF, is not the literary equivalent of "an extended, dramatic composition"(as dictionary.com puts it); in fact, its name signifies a past of pulpish adventures, base entertainments, and corny characters and ideas.

But this is as much of a stereotype as the former idea. As Kramer and Hartwell also make clear, there is no widely-accepted idea of space opera. Like a lot of genres, it is something that we recognize, rather than delimit. Space operas may be "space fantasy," but there can also have rigorous science behind them. Of course, even when grounded in science, space operas are rather fantastical. Even the most logical novum is overwhelmed by the combination of high and low drama that the stories contain. And, for me, the key element of space opera is drama, in space, of course. It is the transposition of two very human sorts of story, the epic and the romance (in the classical sense) into the vastness beyond our humble little planet.

The first SF book I ever read was space opera. When I was about 5 years old I was looking through some books at a yard sale, bored to death of Little Golden Books, Dick & Jane, and even Classics Illustrated comics (I had started reading when I was 3). I saw some paperbacks but they had pictures of swooning women, frowning men in suits, or bucolic scenes that were about as thrilling as watching a tree grow. But then, I found something that I had not seen before: a book with a rocket ship on the cover! It was expensive ($2!) but I convinced my father to buy it, and I brought it home and read it over the weekend, twice.

I have only two clear memories of the book: Jerry's constant need to overcome a string of obstacles, and the small rock hitting their ship. But it inspired me to find more books like it. The adventure was a draw, but so was the combination of drama and different worlds. It was not just the future that was compelling, it was the place, the venturing out to unearthly realms. The aliens may not have been terribly alien, but the otherness of the setting made the adventures more consequential to me.

I eventually abandoned westerns and dove into SF. I soon found that I liked certain types of books: I favored Heinlein over Asimov, Burroughs over Smith, Reynolds over Clarke. The big ideas were cool, but what made the stories compelling to me were the effects on regular people. Heinlein's juveniles were as much about coming-of-age and finding your way as they were about technology and galactic wonders. Burroughs' books, while more planetary romance, and Reynolds more socially-oriented works wedded high and low drama together. That fusion was what drew me to space opera, the mixture of (sometimes bombastic) epicness and (sometimes melodramatic) prosaic in the stories. My heroes were Bill Lermer, Podkayne, Rex Bader, and Tars Tarkas.

A few years after discovering SF I was pulled away from it by my family. When I started high school years later I picked right up back and read more Heinlein, Niven, Cherryh, Poul Anderson. I exhausted my tiny school library's resources, which turned out to be a good thing, because it pushed me out of my comfort zone and, with the assistance of an SF-loving teacher, I branched out and discovered the scope of not only SF, but all sorts of fantastika. But I still sought out stories like those I had looked for in space opera, what we nowadays call "character-driven" tales. I credit my early discovery of space opera with inculcating that proclivity in my reading habits, of the need to know how even the most cosmic,massive events affected regular folks.

That to me is the value of good space opera: thrusting average people into extraordinary situations in a world that might be possible someday. That fusion of spectacle and a good yarn was an excellent basis for becoming a good reader, and eventually a writer. Space opera taught me a few things about life, but more than that, it taught about how to look at life, to appreciate the great and the mundane and how they interacted with each other. Despite the roots of the word, space opera not only entertained me, but got me to appreciate the juncture between the marvels that could be and the people we are.

John H. Ginsberg-Stevens blogs at http://eruditeogre.blogspot.com/ is my writing blog. A frequent columnist for Apex, SF Signal and other sites, he's a writer, husband, Da, ponderer, anthropologist, geek, bibliophile, bookmonger, anarchist, and generally cranky malcontent.

"But there was little sense, in criticism and reviewing of the fifties, of 'space opera' meaning anything other then 'hacky, grinding, stinking, outworn' SF stories of any kind" - Kathryn Cramer & David G. Hartwell, The Space Opera Renaissance (pp.11-12).

"Space Opera" always sounds so majestic when you first hear the term used. It conjures up a Wagnerian aesthetic, a vast, significant drama about to unfold. It evokes a grand canvas of interstellar wonders, of great empires and uncountable fleets clashing for the greatest prize: the galaxy itself! And then, you go to WIkipedia:

"Space opera is a subgenre of speculative fiction that emphasizes romantic, often melodramatic adventure, set mainly or entirely in outer space, generally involving conflict between opponents possessing advanced technologies and abilities. The name has no relation to music; it is analogous to soap operas . . . . "- Wikipedia entry for "Space Opera."

Well, heck. Space opera, while sometimes a magnificent, even ostentatious form of SF, is not the literary equivalent of "an extended, dramatic composition"(as dictionary.com puts it); in fact, its name signifies a past of pulpish adventures, base entertainments, and corny characters and ideas.

But this is as much of a stereotype as the former idea. As Kramer and Hartwell also make clear, there is no widely-accepted idea of space opera. Like a lot of genres, it is something that we recognize, rather than delimit. Space operas may be "space fantasy," but there can also have rigorous science behind them. Of course, even when grounded in science, space operas are rather fantastical. Even the most logical novum is overwhelmed by the combination of high and low drama that the stories contain. And, for me, the key element of space opera is drama, in space, of course. It is the transposition of two very human sorts of story, the epic and the romance (in the classical sense) into the vastness beyond our humble little planet.

The first SF book I ever read was space opera. When I was about 5 years old I was looking through some books at a yard sale, bored to death of Little Golden Books, Dick & Jane, and even Classics Illustrated comics (I had started reading when I was 3). I saw some paperbacks but they had pictures of swooning women, frowning men in suits, or bucolic scenes that were about as thrilling as watching a tree grow. But then, I found something that I had not seen before: a book with a rocket ship on the cover! It was expensive ($2!) but I convinced my father to buy it, and I brought it home and read it over the weekend, twice.

I have only two clear memories of the book: Jerry's constant need to overcome a string of obstacles, and the small rock hitting their ship. But it inspired me to find more books like it. The adventure was a draw, but so was the combination of drama and different worlds. It was not just the future that was compelling, it was the place, the venturing out to unearthly realms. The aliens may not have been terribly alien, but the otherness of the setting made the adventures more consequential to me.

I eventually abandoned westerns and dove into SF. I soon found that I liked certain types of books: I favored Heinlein over Asimov, Burroughs over Smith, Reynolds over Clarke. The big ideas were cool, but what made the stories compelling to me were the effects on regular people. Heinlein's juveniles were as much about coming-of-age and finding your way as they were about technology and galactic wonders. Burroughs' books, while more planetary romance, and Reynolds more socially-oriented works wedded high and low drama together. That fusion was what drew me to space opera, the mixture of (sometimes bombastic) epicness and (sometimes melodramatic) prosaic in the stories. My heroes were Bill Lermer, Podkayne, Rex Bader, and Tars Tarkas.

A few years after discovering SF I was pulled away from it by my family. When I started high school years later I picked right up back and read more Heinlein, Niven, Cherryh, Poul Anderson. I exhausted my tiny school library's resources, which turned out to be a good thing, because it pushed me out of my comfort zone and, with the assistance of an SF-loving teacher, I branched out and discovered the scope of not only SF, but all sorts of fantastika. But I still sought out stories like those I had looked for in space opera, what we nowadays call "character-driven" tales. I credit my early discovery of space opera with inculcating that proclivity in my reading habits, of the need to know how even the most cosmic,massive events affected regular folks.

That to me is the value of good space opera: thrusting average people into extraordinary situations in a world that might be possible someday. That fusion of spectacle and a good yarn was an excellent basis for becoming a good reader, and eventually a writer. Space opera taught me a few things about life, but more than that, it taught about how to look at life, to appreciate the great and the mundane and how they interacted with each other. Despite the roots of the word, space opera not only entertained me, but got me to appreciate the juncture between the marvels that could be and the people we are.

John H. Ginsberg-Stevens blogs at http://eruditeogre.blogspot.com/ is my writing blog. A frequent columnist for Apex, SF Signal and other sites, he's a writer, husband, Da, ponderer, anthropologist, geek, bibliophile, bookmonger, anarchist, and generally cranky malcontent.

Published on March 28, 2011 20:21

March 25, 2011

Can you really tell within a few paragraphs if something is good?

Guest post by Patty Jansen

Many people are surprised when agents and editors say that they often don't need to read an entire story to know that they'll reject it. Some writers are even insulted. But if you read five to ten story submissions a day, and you keep this up for a few years, you tend to develop an eye for picking the 10% or so of submissions that show reasonable promise to pass onto editors. How do you do it? Here is a quick checklist I use to weed out the stories that I'll reject immediately from the ones I'll continue reading—in the first few paragraphs (I usually do read a bit more, or skip to a different part of the story to see if the story redeems itself). I want to stress that this is my list, and that other people may well have different criteria. That said, the issues below will raise their ugly heads at some point in the selection process.

A decent magazine gets hundreds, or even thousands of submissions each year. They typically have a number of first-line slush readers. Those people will see hundreds of submissions. They don't need to read an entire submission to know that they're not going to pass it to the next level. Sometimes they don't need more than the first sentence.

Why?

There is a myth in aspiring writer-land that grammar and style don't matter all that much. That it's the story's content which determines its publishability, and that beautiful prose alone won't sell your work.

Yes, yes, and yes.

That said, what sinks a lot of stories is a lack of what I'll call natural flow in the text. It comes both from not listening to writing advice to taking it way too seriously. It comes from trying too hard to sound interesting and from lack of cohesion in the writing. It comes from tics every writer picks up somewhere along the line.

The most important reason a story gets rejected after a paragraph or two is that there are issues with the writing style and occasionally the grammar.

What do I mean by this, and what sets red flags?

Apart from the obvious (is the text grammatically correct and are there spelling mistakes?), an experienced slush reader will see:

If first few the sentences are unwieldy and trying too desperately to fit in too much 'stuff'. Chances are that the rest of the story follows this pattern. Sure, this is fixable, but a lot of work for the editors, and a lot of communication with a writer who may not be ready for quite this much red ink. Too much effort. Reject.