Tania Kindersley's Blog, page 52

July 17, 2014

The nicest of them all.

At last, my mother is home from the hospital. I lie on her bed and talk of Michael Scudamore, who has died.

‘I can see him now,’ says my mother. ‘Sitting on the lawn, in a director’s chair, drinking Pimm’s.’

I think how racy my mother must have been, to have a director’s chair on the lawn in the late fifties.

‘He was a very good jockey,’ she says. ‘He rode with your father. But the real thing about him is that he was so nice. He was the nicest of them all.’

Nice is considered a poor word. Writing manuals strictly instruct you not to use it, not if you want to be taken seriously. I like it. It is a small, humble, unassuming word. It does not show-boat, or take up all the oxygen in a room. And it does, whatever the sneery received wisdom says, mean something.

When I was young and heedless, I suspect I probably agreed with the sneerers. Who wanted to be nice? It was so dull, so safe, so workaday. Much better to be charming or wild or reckless. Now I am older, and chipped around the edges, I crave niceness. How lovely and reassuring to be nice, in a rushing, technological world, where internecine battles break out at the drop of a hat, and trolls stalk the internet, spreading their bile.

He was a nice man, Mr Scudamore, and that is a proper epithet for a gentleman of the turf.

My mother tells me about Dave Dick, who was the joker of the pack, and drove a car like a maniac. ‘He never had his eye on the road,’ says my mother. ‘He was always looking at you to see if you got the joke of the week. Oh, I was so frightened.’

‘Fred Winter was my hero,’ says my mother. ‘Because of how he rode a horse. He was the most beautiful jockey I ever saw over a fence.’

She pauses, remembering. ‘Then Francome came along. And he was beautiful too.’

I remember watching John Francome ride. There was a poetry in it.

‘The one I love watching at the moment,’ I say, ‘on the flat, is Ryan Moore. I watched him educate a two-year-old colt in a race the other day. He took him through the whole thing, very gently, step by step, letting him find his stride, sitting perfectly still, and then picking him up a furlong out and letting him rock into a flying rhythm and showing him his business. He won, and he never picked up his whip, just hands and heels.’

‘So the horse would not know he had a race,’ says my mother, smiling. ‘Scobie Breasley used to do that. He was a genius with two-year-olds.’

We talk of the Hannon two-year-olds, and how beautiful they are. Many trainers have a stamp of a horse. You can often tell, seeing the mighty creatures in the paddock, which yard they come from. The Hannons love big, strong, close-coupled horses, very deep through the girth, with short, powerful necks and finely-carved heads. ‘And Mark Johnston,’ says my mother, ‘likes those honest, long horses, rather old-fashioned types.’

‘Who look as if they might go hurdling,’ I say.

Almost under her breath, almost wistful, my mother says: ‘The most beautiful of them all was Frankel.’

We remember Frankel, as if we are paying homage, which in a way we are.

‘They have a presence,’ I say. ‘Those great ones.’

‘Nijinsky had it,’ says my mother. ‘You could feel it the moment you stepped onto the course. Although he wasn’t much fun to see in the pre-parade ring.’

‘Because he got so lathered up?’ I ask.

‘Oh,’ says my mother, indulgently,as if describing a naughty schoolboy, ‘he got himself in such a state. But it never seemed to make any difference. He just went and won anyway.’

‘Michael Scudamore,’ says my mother, reverting to our point of origin, ‘made a dynasty. Imagine that. His grandson is riding now.’

‘Tom Scu,’ I say. ‘He’s a lovely jockey. And a gentleman too.’

We contemplate the Scudamores, the nicest of them all, a family which knows horses like sailors know the sea. I think of the brothers, who only this week carried the coffins of their grandfather and grandmother into a Norman church. The old lady died, and her husband followed her three days later.

What loss they must be feeling: two blows coming so close together, two mighty oaks felled. I look out at the sunshine. It was sunny like this when my father died, that impossible, improbable sun which is not supposed to shine on dear old Blighty, not on these islands of mist and rain. The Scudamores must have that same feeling of unreality that I remember so well. They must be looking out into the blinding light and waiting for the world to make sense again.

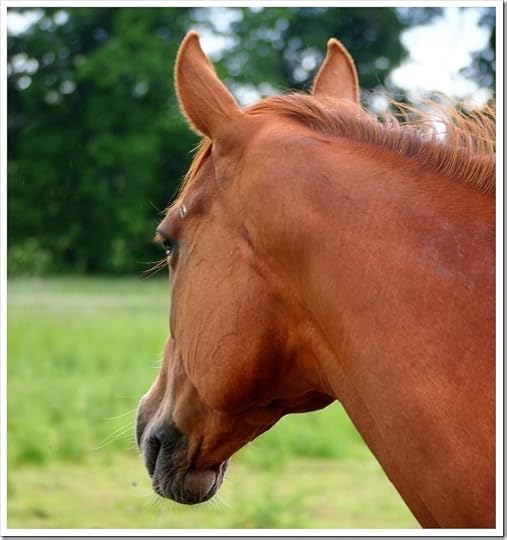

Today’s pictures:

The red mare is having a well-deserved day off. Today, she just gets to be a horse, out in the long grass, with her dear friend for company and the sun on her back:

July 16, 2014

PS.

I have that undefended, deflated feeling which comes after too much excitement. It is like a child going to a party. You eat too much chocolate cake, do a tap dance, play kiss-chase with all the boys, and, as your mother predicted, there are tears before bedtime.

I am prone to passions. When one has me in its grip, I feel certain that it must be shared. There is a regrettable lack of editing or restraint.

Afterwards, as the waves of angst crash on the shore, my sensible mind says: nobody has to read it. It is your blog. It is free. And maybe someone who is having a shitty day will smile. And maybe someone who is feeling dislocated might sigh and say: me too. And maybe there is a life lesson in there somewhere.

That is the hope.

Here is the fear, which comes from the snapping jaws of the irrational mind. There you are, says the fear, which is a hag-bitch from hell, banging on again. On and on with the monomania. Not everyone has to know. You should just think these things, and not write them all down. People have lives to lead, and not enough time. It’s just a DAMN HORSE.

Sometimes, the rational mind fears the irrational mind may have point. This is one of those times.

I also had angst because I suddenly thought I had pushed the mare too much. I had asked a vast deal of of her. I went down to the field and stood with her for a long time, rubbing her and relaxing her and putting her to rights. I apologised, just in case. She wibbled her lower lip and sighed. I interpreted this as a sign of forgiveness.

I apologise to the Dear Readers too. I really will write of something else. You are kind and good and you put up with a lot.

Don’t apologise, bawls the defensive brain. Don’t show weakness. Once there is blood in the water, the sharks will gather.

But frailty is part of the human condition. Vulnerability is what makes people interesting. There is no point building a castle keep and retreating inside it. The passions make me stupidly vulnerable, and there is no point pretending they don’t. It was a big day, and I told it in too much detail, and now I am crashed.

Miss Overshare sends her regrets, like Miss Otis.

But the lovely thing is that tomorrow the sun shall rise again, and with it shall come brevity and pith.

The Great Moment.

Warning: this is crazy long. It also involves an awful lot of horse. It’s a story I really wanted to tell, and it has taken many, many words. Feel free to skip on and come back tomorrow, when there will be pith.

The Great Moment arrived.

Of course, in the manner of so many great moments, it did not turn out quite as I had dreamed it. There was no swoony Disney effect, with a sweeping string section and not a dry eye in the house. No Hollywood producer, had she been passing, would have stopped and said: ‘I must make a damn film out of that.’

It was very ordinary, and very, very sweet.

I’d worked the mare on the ground and under the saddle for a long time in the morning, to prepare her. She did an enchanting free-school, with floating transitions between walk and trot from my body only, and then hooked on and walked round the field with me, her head low and her ears in their donkey position.

In the saddle, I did something which I should have been doing every day, and have not. As I learn this new kind of horsing, I get so excited that I skip parts and jump around and do not do the things in order. Let’s do that today, I say to myself, galvanised because I’ve just seen it demonstrated. Or let’s try this, just for fun. In fact, one should roll through the foundational steps, in their right sequence, every single day, as automatically as if one were brushing one’s teeth.

I finally got the message, and put into action one of the most brilliant techniques I have ever learnt. It is a mental thing. You get on your horse and you say: where would you like to go today? The horse moves off. Usually it will go to the gate or where the feed is or the place where its buddies are hanging out. When you get there, you make it work. You disengage the hindquarters and turn it in tight circles and, as Warwick Schiller says, the brilliant Australian horseman from whom I learnt this method, annoy the hell out of it. Not in a mean way, but just because you are continually asking something. Then, when you are facing away from the favourite spot, you let it go on a long rein and the moment it moves off, you leave it alone. You go from work, work, work, to bluebirds and butterflies.

Sure enough, Red wanted to go to the top gate where the feed lives. Circle, circle, circle. She got the message very quickly. Off we went in the opposite direction, on the buckle. Then she tried the bottom gate, where the grazing is. Circle, circle. Then she tried her little paint friend. Circle.

She is so clever that she got it at once, and she stretched out her duchessy neck and strode off, athletic and relaxed, to the easy places.

I love this method because it means you are not saying no. You are saying: of course you can go over here if you want, but if you do, there will be work. On the other hand, if you go over here, where I want, there will be only lightness and ease. It’s what Buck Brannaman calls offering the horse a good deal.

Usually we have a bit of an argument as we leave the field. She wants her breakfast; she wants her pal. I want to go riding. Argy, bargy. Today, because I finally went back to proper basics, there was no argument, only a polite conversation.

It also has the miraculous ability to relax them. I’m still not sure entirely why it has this effect, but it is as if some lovely Zen mistress has come and sprinkled cooling fairy dust in the air.

Out in the hayfields, we did another foundational exercise, again of a simplicity so delightful that a child of nine could do it. If your horse wants to go left, you turn it right, and vice versa. Again, the miraculous relaxing. We did this out in the hayfields, and at one point she actually breathed out a gusting sigh of happiness and relief.

This was the preparation. I write it all down because the work to get to the Great Moment was as important as the moment itself.

Into the brave new world we went. It was twenty times better than yesterday. There was no snorting, and no spooking. Buses honked and hissed, tractors and trailers clanked past, bicycles whooshed by. The red mare twitched her ears and walked boldly on. We met another tiny child. There was the same awe-gazing that we had seen before. My heart, as it always does when I see this look cast upon my beautiful red girl, flew into the light Scottish air.

Down to the care home we travelled, going kindly within ourselves. And just as we arrived, and I was about to break out the swoony string section in my head, the mare, with perfect bathos, lifted her aristocratic tail and took a huge dump right by the tubs of begonias.

I let sentiment go by, and laughed and laughed. ‘Good for the roses,’ said one of the carers, staunchly.

Out came the old people. All of them were suffering from the various indignities of age, as time ruthlessly ravaged their minds and bodies. Some were in stages of dementia, some had physical infirmities. Some had words which made no sense; some had no words at all. One or two were hovering on the cusp, just holding on before the final infirmity caught them in its crocodile grip. They came out with sticks and walking frames and wheelchairs. The carers, capable and brisk, said: ‘Look, here is a horse. A HORSE.’

‘This is Phoenix,’ I said. ‘She is a thoroughbred.’ And, I’m ashamed to say, I told them, because I can never resist it: ‘Her grandfather won the Derby.’

‘Hello, Felix,’ said a chorus of amazed voices.

She did not, as I had slightly hoped she would, at once stick her dear face out and tickle them gently with her whiskers. She was a little astonished by such a gathering of strangers. A great murmuring had broken out, a chorus of exclamation. It was a very familiar sound to me and it took me a moment to realise what it was. It was the exact same noise that the crowds make when they gather round the winner’s enclosure at the races. At last, I thought, this finely-bred racehorse, who trundled round the back at gaff tracks, is in the winning circle.

Like a winner, she caught a wing of adrenaline, and stuck her head in the air and let out a calling whinny. The old people found this hysterical. They smiled at her and laughed at her and gave her carrots. She was a little restless, more reactive than I would have liked, but it was a small space, filled with humans she had never met before, and, considering it was only her second visit to the village, I thought she comported herself amazingly. She took the carrots and amused her audience by flinging little orange scraps about the place as she chomped.

It was not quite the Disney moment. She did not lay her velvet muzzle on a frail old hand and let out a low breath of recognition. She was not yet relaxed enough for that. But she will be, in time. We shall go again, and she shall get to know them, and I’ll work sternly on those foundations, and we’ll get that magic moment.

It was an ordinary grey day, in an ordinary little village, outside one of those ordinary buildings thrown up in the 1970s with no thought for aesthetics. It was an ordinary group of humans, carrying the ordinary afflictions of age. It was an ordinary horse, with her ordinary rider.

It was not a movie. It was real life. And damn, she did make those people laugh and smile.

Today’s pictures are a photo essay of the morning:

Before work:

After desensitising:

Free-schooling. Notice her ear turned in towards me:

Transitioning down to walk:

Hooking on:

Resting, after all her good groundwork:

Out into the hayfields:

At the care home, I walk away to take pictures. Big whinny. WHERE ARE YOU GOING????:

And what’s over there?:

Well, I suppose it is all right:

Are we really on the Deeside way?

Answer: yes. And there is the village:

And the hills:

And the long view east:

And back to the village again:

Going home:

The end of the mighty ride. She can hear her little Paint friend calling:

Hosed off and shaking it all out:

And having a well-deserved pick in the long grass:

There is a postscript to all this.

Because I had made my offer to go to the old people, I really had to go back and concentrate on the work I do with this mare. You can’t just take a thoroughbred on a mission like that and kick on and hope for the best. I grew up in the old school of kicking on and hoping for the best, and I don’t disdain that. Using those traditional English methods, I did dressage and working hunter and cross-country and showing and won many red ribbons and silver cups.

But I like this new school because it has a simple solution for every problem. The minute you see the world through the horse’s eyes, everything can get fixed. I find a delightful utility in it. I like it too because although I think of it as a new school, it is in fact very old. It does not belong to anyone. The great horsemen are like aristocrats with their stately piles: they are not owners, they are custodians, passing on the wisdom to the next generation. The knowledge that I now use was passed along by Ray Hunt and the Dorrances, men whose names I did not even know until two years ago, men now departed on whose sage words I hang.

Through the miracle of the internet, one of the holders of that flame makes it available to neophytes like me, in a practical, easily accessible form. I went back to the school of the magnificent Mr Schiller and did not muck about this time. The mare and I had a serious purpose, and I could no longer be cavalier. I had to be rigorous, and follow the steps. The difference in my horse was immense.

The discrete purpose had a lovely unexpected consequence. It set us free. Even though I’m very proud of everything the mare has achieved, I still was conscious that I had a great, powerful thoroughbred under me. Because I am still in the learning stage, there were days when she could be unpredictable. I am middle-aged, and I have not ridden seriously for thirty years. I saw no reason to take unnecessary risks. We kept to the safe places, the quiet fields and tracks near home. The main road was a Rubicon for us; there was no thought of crossing it. Why should we? We could play in the hayfields and the sheep meadows and the home paddocks.

After we left the care home today, I took her out on the Deeside way. I would never have dreamed of doing this before, in a million years. Why not? I thought, seeing the sign; let’s just go. And suddenly there were the bright open fields and the long blue hills and the unknown spaces. And there we were, in them, on a loose rein, in perfect harmony.

I realised that I had been hamstrung by fear, by horrid imaginings, by doubt. But because I had gone back to the beginning, and concentrated my mind, and applied the proper techniques in the proper order, I was utterly liberated. We could go anywhere, in our rope halter.

She had a bit of a look, and a bit of a tense, and then she took confidence from me and walked out, easy and relaxed, with that lovely sway of pride that the fine ones have.

Who would have guessed, I thought, that a visit to the old people would have set us free?

And finally, this quote about the horse from Ray Hunt is like a prose poem. I’m going to recite it in my head every morning:

‘You want your body and his body to become one.

This is our goal.

It takes some physical pressure naturally, to start with, but you keep doing less and less physical and more and more mental. Pretty soon, it’s just a feel following a feel, whether it comes today, tomorrow or next year.

So one little thing falls into line, into place.

I wish it would all fall into place right now for you, but it doesn’t because it has to become a way of life.

It’s a way you think.

It’s a way you live.

You can’t make any of this happen, but you can let it happen by working at it.’

July 15, 2014

What do you think?

I need to do some crowd-sourcing for one of the secret projects. Even though they have both now been read and green-lit by the agent, they still feel like secret projects to me. I rather enjoy this small absurdity, as if, in the mazy corridors of my own mind, I am an International Woman of Mystery.

The crowd-sourcing is because I have read the experts, wrangled my own brain, mined close, observed experience, and now I want the view from the internet. This is where the internet is brilliant. In my own tiny corner of it, I find people I should never, ever meet in real life. There is the intensely kind lady in Sri Lanka, who is one of the original readers of the blog, and the brave woman who went through the Christ Church earthquake. There is the Dear Reader in Canada, who also loves horses. There is the number one Stanley the Dog fan, and the lady who adores chickens. There is my friend in the north, who knows all about animals breaking your heart, and missing departed fathers. (I say friend, because she feels like a friend. I don’t expect we shall ever see each other, face to face, but that is how this odd intimacy works.) There are my blogging sister-in-arms, some of whom I have actually met, but whose support comes most keenly through the ether, which is our place of mutual connection.

I feel that connection, with everyone who comes here, and one of the things I think over and over again is what a great leveller the internet is. We may have very different life experiences, but it comes back to that meme which did the rounds a while ago: be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle. I feel that everyone here is fighting their battles. There is death and divorce, professional set-backs, illness and physical pain, aging parents and the daily frets of bringing up children. Everyone, it strikes me, is really trying their best, sometimes against long odds. There is a lot of quiet courage, and a lot of stoical grace.

Because of this, I sense there is a wisdom in this crowd, and that is what I want to tap.

My subject today is irritation. I was thinking about the things that drive me nuts in the head. I was thinking about the human things which are the most annoying. I don’t mean the big catastrophic faults, like war crimes and corruption and corporate greed. (Although, this morning, I felt a twisting spasm of rage at the man in charge of Nestlé, who has said that water is not a human right.) Those are horrors, and deserve a stronger emotion. I don’t even mean things like unkindness, which is a serious ill and should be regarded with gravity. I mean the small things which don’t really matter, but which produce a disproportionate response. I mean the things which make you want to throw heavy objects, and then, afterwards, you say to yourself in puzzlement: what button did that press?

On my own list would be: people who do not listen, people who are rude generally, but in particular to waiters, people who look over your shoulder at parties to see if there is someone more interesting or important to talk to. Also: personal remarks, bad-timekeeping, dangling modifiers, jargon, condescension, smugness, and being cheap. I get the nails on the blackboard feeling from people who say one thing and do another, who never listen to the other side of the argument, and who jump on bandwagons, particularly those that involve conspiracy theories or intellectually lazy received wisdom.

But at the moment, my number one, five star, ocean-going, fur-lined bête noire is: people who offer unsolicited advice.

Why should this drive me so demented? It really does not matter, in the wider scheme, not when Israel and Palestine are going up in smoke, and the refugee camps spread on the Syrian border, and Mr Putin grows daily more unpredictable. It produces a visceral reaction, a desire for violence, when I am by nature a pacific person.

I can perfectly well listen to it and let it go. I do not have to follow it. I can politely nod and smile and ignore it. But oh, oh, it makes me want to scream and shout.

I think: why would anyone tell another human what they should be doing when they have not asked? Why should someone think that other people are such idiots that they cannot manage their own life or make their own decisions or know their own minds? To me, it is the height of bad manners. The implication is that they are such fools that they need a dose of superior wisdom in order to straighten themselves out. It is, psychologically, an act of aggression. It is an invasion of personal space. It is a denial of autonomy and agency. It is a way of saying: I am brilliant and you are stupid. It is almost a negation of self.

I need to go back and have a hard search in the darker regions of my soul, in order to work out why this small irritation makes me go bat-shit crazy. Almost certainly it is some kind of failing in my own self. I have many failings. But one thing I can say with certainty is that I have never, ever told another person what to do unless they have requested the advice. I think it is an affront.

The line that comes to me now is – I am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul. I smile as I write it. No busybody, however well-meaning, can take that away from me.

I want your own irritations. Will you tell me? I am consumed with anticipation and curiosity to know what they are.

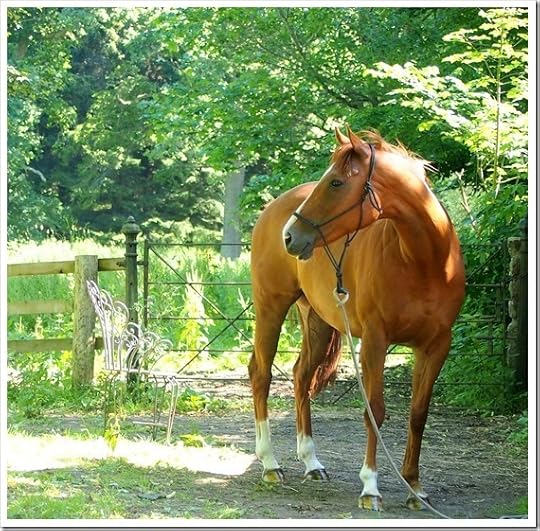

No time for pictures now, just this one of my best beloved:

We did our big practice run into the heart of the village, to get ready for the old people tomorrow. There were huge hissing buses, rattling dustbin trucks, squealing schoolchildren in high-visibility vests, men hurling building waste into industrial skips, and all sorts. The red mare spent her competitive life on quiet grass, working always with other horses, away from the hurly-burly of humans. Until she came to me, she had never been out on her own or seen anything busier than a tiny country lane. This was a lot of stimuli for a sensitive thoroughbred.

All the hard graft I have been putting in paid off. She was a little more reactive than I would like, which means I need to go back and check my working. She had a damn good snort and a look around. But the lovely fact remains that I took a fine thoroughbred into a completely new environment, riding only in a rope halter, and for all that she was sometimes uncertain and alarmed, she listened to me. I was very, very proud of her.

In a most touching moment, she stopped kindly and made friends with the small children, and she stood graciously and sweetly as they gazed up at her and stroked her nose. ‘She is very big,’ said one. ‘And very beautiful,’ said another.

Then we met a smiling old lady. Again, we stopped to talk. The lady told me that she had been in signals, in the army, in 1946. ‘With Louis Mountbatten in South-East Asia Command,’ she said, beaming. ‘It gave me a taste for travel. I’m off to Africa next week.’ I was so awe-struck by this extraordinary piece of information that I reverted to the language of my teen years. ‘That is so cool,’ I exclaimed.

She smiled up at Red, and gave her a gentle stroke down the neck. ‘You know,’ she said, ‘I’m afraid of horses. So that’s something.’

That is something. I rode home grinning all over my face.

July 14, 2014

Brick by Brick. Or: of horses and grammar and small things.

As I am taking the red mare to the village on Wednesday for her first visit to the old people’s home, I am spending a lot of extra time working with her, to make sure she is ready for the Great Moment. I am going right back to the foundations, and checking that they are dug deep.

In this remedial horse work, I have been reminded of something very important. It is that it is crucial to get the little things right, so that the big picture becomes a joyful one. If you get sloppy or careless or hubristic, the whole thing cracks and crashes.

Every time you take a step with a horse, you are teaching it something. That is why the small things are so vital. I keep thinking that this must apply to human life too. When I write a book, I do an entire semi-colon edit. I make jokes about this, because it is so absurd and anal. But one punctuation mark in the wrong place can make an entire sentence collapse.

I’ve heard people say that insisting on correct grammar and spelling and punctuation is the elitist howl of the snob and the pedant. Yet language should sing, and it cannot do that if the apostrophe’s are incorrectly placed. (Do you see what I did there?) Prose has a rhythm and syncopation, like music. I listen to it with my ear as well as read it with my eye. Sometimes, I will change one syllable, because it throws the beat off.

Stern, joyless grammar is empty and wrong. Sometimes, an infinitive should damn well stay split. Twisting yourself into a pretzel to avoid ending a sentence with a preposition can be a pointless task, and can deaden the words on the page. I still insist that the general rule of correctness holds. Paradoxically, it is liberating, for the writer and the reader. The reader need not worry that the eye will be arrested, nor fear she will be yanked out of the fictional world by a howler. If the words flow in the right order, and the commas are nicely placed, and the apostrophes do not belong to the grocers, the reader will have the delightful subliminal feeling of comfort and ease that comes from being in safe hands.

For the writer, knowing the foundations are fine and sturdy means that the imagination can fly. If you are constantly stopping to wonder whether that modifier is dangling, or whether this colon is ill-timed, you cannot let yourself canter across the prairies of invention. Only when you know the form can you play with it. Then, confident, you can throw the language of Shakespeare and Milton into the air and watch it fall.

I galloped my red mare this morning, out in the hayfields, on a loose rein, as a reward for all her hard work. I let her go, and boy, did she shift. I could do this because I had run through twenty tiny checks on the ground first, from yielding her hindquarters to lateral flexion. Only when all that was working, and she was sweet and relaxed and responsive to a soft cue, could I let her run. She was confident and I was confident, and we flew over the shorn grass like the swifts that played over our heads.

I talk a lot about the small things, in the context of happiness. If I can love and notice the moss, the trees, the moving clouds, the song of the birds, then I know that I am in a good place. Now I see the small things matter in the context of work and achievement too. Start with the tiny steps, and you can climb to the highest peaks. It’s what Emperor Hadrian said about the building of Rome. Brick by brick, my citizens. Brick by brick.

July 11, 2014

The universe sends an unexpected present.

A few days ago I wrote that the only thing to do in the face of the madness of the world is to find your one small thing which adds to the sum total of human happiness, and to do it.

Since then, I have been in a non-specific fury. The world news is bad, my poor mum is still in the hospital, my beloved Arab Spring got stuffed yesterday, with my money on his bonny back. I was going to deal with the jangles by drinking some gin last night, and getting sloppy drunk, but better angels prevailed and I went to bed early and got up with the sun.

As the red mare and I continued to take one glorious step forward, and one prosaic step back, I had returned to my internet horse training guru, the brilliant Warwick Schiller, and looked at some of his amazingly helpful videos. There were two things that stood out to me. One was the importance of balancing your horse. The other was making it do more than you do. (This is a clever idea based on herd psychology.) It also chimed with something another wise Australian, Ian Leighton, had written not long ago, about love and horses. He was concerned that some people get a bit soppy with their equines (at which point I mentally shuffled my feet and cleared my throat) and confused good, honest, tough love with the sentimental sort, which does a horse no favours. Horses need good boundaries; it makes them feel safe.

With all this in mind, I girded my loins, and went out into the glorious Scottish sunshine.

The mare was soft and sweet. I was patient and rigorous. I did not skip a step, but went slowly through the foundations. I got on, and all the scratchiness was gone. There was my lovely, easy, confident girl again. Two days ago, she leapt in the air at the sight of a duck. Today, she walked past a strange man wielding a loud strimmer, dressed as if he were attacking an outbreak of Ebola in a disaster movie, without twitching an ear.

And then, out of the clear blue sky, the universe sent me my one small thing.

We came across a care worker pushing a very old lady in a wheelchair. The old lady was clearly not well, and beyond speech. But she looked up at my mare, and the shadow of a smile crossed her ancient face. A fleeting gleam came into her empty eyes.

The care worker and I fell into conversation. The red mare stood stock still, occasionally bending her dear head to regard the old lady with gentleness. A line from Yeats came into my head. ‘Dream of the soft look your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep.’

‘Do you think,’ I said hesitantly, to the care worker, ‘that your old people would like it if I brought the mare to see them one day?’

I am an absolute pushover for therapy animals, in particular service dogs. One of the beautiful things about the internet is that these wonderful creatures are brought daily to my eyes, as I see pictures of sweet canines in hospitals with the gravely ill, and great guide dogs, and brave Labradors working in the dust of Helmand. Horses too are increasingly used in service roles, with autistic children, and people with special needs, and even young offenders. I see their power every week, in my work at HorseBack, especially with those who are fighting the long fight with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. I’ve often thought that I should like the red mare to go to the old people’s home, but have always been too shy to ask.

The care worker looked delighted and amazed. ‘Would you do that?’ she said. ‘They would love it.’

The red mare is going to be a therapy horse.

I kept my countenance and finished the conversation and politely said goodbye and moved off. The mare was relaxed and low under me, her lovely neck stretched out, her stride easy and free. The sun dappled through the trees. In the distance, the blue hills glimmered in the light.

‘You amazing girl,’ I said, out loud. ‘You are going to be a therapy horse.’

I wonder sometimes what all this striving is for. I want a happy horse, I want to be able to do everything with her using only my little finger, I want to be able to go down to the field and leap on her back without having to fear catastrophe. That, of course, is the point. But sometimes, when I am a bit jangled up, I get confused, and think that I must show off. That’s when I start posting endless stupid updates on the internet, begging for praise. That’s when I think I should school her for some competitive purpose, so that we can win prizes. Perhaps, lurking in the back of my mind, there is her mighty pedigree. When they bred her, they must have thought she could win the Oaks, even the Arc, with all the titanic middle distance champions that inhabit her bloodlines. She ended up trundling round the back at Thirsk. Perhaps there was a part of me that felt she should finally live up to her aristocratic billing. I don’t know.

All I know is that, in that moment, everything fell into place. This, this, is what all the work is for. It is so that a fine thoroughbred can calmly go into the village and put her dear head through the window and make the old people smile. That is the point of the desensitising and the balancing and the endless groundwork, and my dogged attempts to make myself a better horsewoman.

‘You beautiful, clever girl,’ I said. ‘That is your one thing.’

Sudden tears came, I’m not sure why. For all of it, I suppose. I was blinded. I had to take off my spectacles. The good horse walked on, finding her own way, until I had gathered myself again.

I believe that horses feel pride. You can see it in some of the great champions, as they lift their heads and prick their ears after the winning post, and turn to regard the cheering crowds. The look of eagles, my mother calls it. Desert Orchid had it, and Kauto Star, and Frankel. ‘He really soaked it all up,’ Tom Queally once said of Frankel, after his storming victory at York. ‘He knew he was the man.’

As I felt the gladness pour out of me, I sensed pride in my red mare. It was very quiet, and very contained. But it was there. She is going to be a damn therapy horse. I could kiss the sky.

Today’s pictures:

Before the ride:

Hosed off and relaxed afterwards:

Synchronised grazing:

July 10, 2014

Rage.

I am in a rage today. I have no idea why. There is something about which I am furious and I have no idea what it is. The red mist is swirling about me. My whole body is tense and livid.

I write here sometimes about moods. I like to think I don’t really do moods. I like to think that I feel emotions in their appropriate places. If something sad happens, I feel sad. If something good happens, I feel happy. I am a fairly simple soul. Quite rarely, but quite acutely, I sometimes wake up in a fog of paralysed gloom, for no reason at all. I can’t fight my way through it. The only thing to do is to sit and suffer until it passes. If I were a better psychologist and had paid more attention to my Jung, I expect I should be able to get to the bottom of these mysteries, but I can’t.

Today, it is fury. It’s been brewing for a while, leaking out about the edges. I am lacerating myself, castigating myself for not coming up to scratch. It is not specific, just a general sense of being useless and pointless and feckless. I am ashamed to say that I shouted at the dog. (Luckily, he is a lurcher, so he just gives me his lurcher look, and carries on with his business.) I even had a moment of irritation with the red mare today, and had to walk quickly away from the field before I did something I would regret. She is the love and light of my life. How can I feel cross with her?

It is a beautiful sunny day, and I have written 1503 pretty good words. I have all my arms and legs. I live surround by ancient blue hills. I do not have to walk ten miles each morning just to get water. My good fortune is ridiculous. How can I feel anger in the midst of such bounty? I have done all my work and am going to give myself the luxury of watching the July Meeting at Newmarket, where some of my favourite horses in the world are gathered. I shall be able to watch soaring beauty on that storied green turf. I should be in a maze of joy.

Instead I want to kick things and throw things and shout fuck fuck fuck fuck at the top of my voice.

I suppose this is called: being human. I once wrote that the mark of being a grown-up is the ability to sit with uncomfortable feelings. As I say, over and over again, every day can’t be Doris Day. This is more Doris Karloff.

Ah well. Deep breath and count to ten. If dear Arab Spring can fulfil his promise and win the 2.40 then all manner of things will be well. If not, then I don’t know what will happen.

Just time for one picture, before the racing starts. Here is the duchess, shaking off those damn horseflies which are out to get her. I feel pretty much like she looks:

July 9, 2014

One thing.

Sun shining; red mare worked; breakfast for lovely stepfather cooked; 1746 words of book written; HorseBack work done.

My mum is on the mend, which is a huge relief for all of us.

I have a new hard deadline, so am galloping through my days like a sprinter at full stretch. Today, the brain has gone snap since I fear I hit the front too soon, so there are no words for you.

I did have one thought, which I may be able to articulate. The news is very bad at the moment. The news is often bad, but it seems especially acute this week, one horror story is piling on another, particularly with what is going on between Israel and Palestine, and the terrifying revelations of the child abuse cover-up here. In their different ways, they are stories which leave an individual feeling a catastrophic combination of rage, sorrow and sheer helplessness. At times like this, it is easy to fall in the slough of despond, and believe that the puny human heart is no match for atrocity.

What does one do, in the face of that? I think, although I am not sure, that it is important to find one thing, however small, which contributes to the sum total of human happiness, and to do it. You can’t save the world, or stop the hatred, or fix the dark side of the psyche. But if everyone does one thing, then miracles may happen.

That is why I go to HorseBack. I do it for many reasons. Perhaps the most vivid is because I am so filled with admiration for the veterans I see there. They have waded out to the wilder shores, and have courage and grace that I shall never know. But since I have been volunteering, I realise that it is a largely selfish act. It is so that I do not collapse into a puddle of despair, every time I see the news.

Find your one true thing, and do it. It’s not much of an answer, but it’s the only one I have.

Today’s pictures:

Are a rather random selection from the archive:

This one is all blurry and out of focus, but I love it, because it is filled with happiness. It is my oldest brother and my mother, at her 80th birthday party:

Stan the Man does high nobility:

And hard-core DON’T MESS WITH THE STICK:

Sweet questing face:

Ha. I suddenly realise I have at last written a whole blog without banging on about the red mare. I should hang out more flags. *faints with disbelief*

July 8, 2014

Red mares and life lessons.

Author’s note:

This is for the horsey ones. To the other ones I apologise and say please do come back tomorrow. It does contain some human life lessons, but it centres around the horse. It is also absurdly long. So sorry about that.

The kind of horsemanship I practice has many names. The one that people seem to dislike is natural horsemanship. I can see why. It is a contradiction in terms. There is nothing natural about horsemanship. You are taking a herd animal out of its native habitat, strapping a bit of another animal to it, this one dead, and asking it to perform actions it would never dream of in the wild. You carry your hands exactly where its predators sink in their claws when they strike. You stroke it in the exact place that those predators plunge in their sharp teeth, to sever the spinal cord. Just because you keep it in a field and work with it at liberty and try to mimic its lead mare does not mean any of this is natural. That is why working with a horse is so elemental and astonishing, because, mostly, it gives its consent to all this.

I think of this new horsemanship, which is in fact very old but never had a name before, as mostly practical. Sure, I get a bit misty and hippy from time to time, and think about the universe, and believe that my mare contains it in her deep eye. I like to believe that these methods have taught me to understand her and be in harmony with her. But mostly, they have a strict utility. I grew up in the old school, where the solution to most problems was hard schooling and more tack. The idea was that you got so good at riding that you would not come off when they bronced or bolted or bucked. If a horse was a rearer, it was a rearer. If it was a spooky bugger, it was a spooky bugger. If it was a bolter, it was a bolter, and you either rode it in the strongest bit you could find, or you just stuck on and prayed. There was absolutely no notion that you could change any of these behaviours. You might be able to teach a horse to settle in a race, to conserve energy, and you could brush up its jumping; you could educate a pony to go on the bridle, and make some nice transitions; but that was it.

This new school says that you can get a horse so relaxed and responsive that it will not pull, or buck, or shy, or rear, or charge off into the blue horizon. You can teach it not to barge, not to rush, not to bash into your personal space. The techniques for this are not complicated, but they require a lot of patience, consistency, thought and time. You can’t get lax or skip bits. You can’t take your frets and tensions down to the field and expect your horse not to notice. You have to be your best self, the good leader, who will keep your kind equine safe from mountain lions.

The red mare has been a bit reactive and tense in the last couple of days. She went from dozy old donkey, walking out so relaxed that I dropped the reins and the irons and just rode her with my body, to fired-up thoroughbred, snorting and staring and jumping at shadows. She even did a fabulous cartoon spook at a duck, with skittering hooves and airborne leap, something she has not done for months.

Well, I thought, she was a racehorse. Her grandfather did win the bloody Derby. I’m still riding her in a rope halter. We have not ended up halfway to Inverness. And she is a horse, after all, whatever human methods I apply to her.

There is a tremendous Australian horseman called Warwick Schiller, whose precepts I follow. There are many great horsemen and women on the internet, and I learn avidly from all of them. Some of them are no longer here, but their words and wisdom survive, in the ether. I learn from the late Ray Hunt and the Dorrances; I learn from the very much alive Buck Brannaman and Ian Leighton and Richard Maxwell and Robert Gonzales.

Schiller is particularly good, because he puts up practical videos, where one can see the ideas in action, and he also has a forum, where he patiently answers endless questions about groundwork and lateral flexion and all sorts.

On this forum, yesterday, I posted a question. Will a horse always be a horse, I asked, and have its moments of reaction to unexpected stimuli, or, if you are doing everything right, should it remain relaxed and soft and focused? I think I was looking for excuses. I think I knew the answer to my own question. I think I knew that when the tense snorting comes, it is always to do with human failing. Still, everyone was thoughtful and kind, and people wrote of the importance of building the foundations and remembering to take Square One with you wherever you go and minding your body language and getting your head straight.

Inspired by these good reminders, I took the red mare out this morning and went through all the foundational steps, one by one. I did not let anything slide. I was firm and rigorous and fair and even. I thought a lot about feel, and practised it. And I got my lovely, low, easy girl back again.

SUCCESS, I shouted in my head, like John Malkovich in Dangerous Liaisons. Success. We were Olympians; we were Grand National winners; we were golden.

And then, fatally, I got cocky, and pushed her a little too quickly, and everything fell apart. I could not get the canter. Her stride was all broken up, her head was in the air, her neck was braced, she was rushing and pulling and not listening to me. I had envisaged a beautiful cowboy lope, and instead we had a Calgary Stampede plunge. (My old dad once rode in the Calgary Stampede. It was not his most glorious moment. ‘On for nine seconds,’ he said, laconically, afterwards; ‘and out for nine hours.’)

I was furious with myself. Fuck bugger bollocks and arse, I shouted in my head. My unbalanced horse was all over the shop. Her unbalanced human was all over the shop. Failure, I thought bitterly. Failure, failure, failure.

I took a deep breath, and went back to the beginning. We are going to be here for hours, I thought, in rage and I’ve got work to do. I counted to ten. I did the lateral flexion. I got the easy walk on a loose rein. Her ears flicked back towards me, listening again. I thought beautiful thoughts and relaxed my body and invited her into a canter, trying not to expect the awful ragged gait we had just suffered through.

And suddenly, like a miracle dropping from a fine blue sky, there it was – light as air, easy as breathing. ‘Yes, yes,’ I said, out loud. The reins were loose, and I kept my hands soft, opening the door for her. She went through the door. She was carrying herself. I went with her, keeping out of her way, letting her feel the confidence of being a horse at home in her own powerful body.

We went round again to check it was not a fluke.

It was not a fluke. We were flying like the swallows which swoop over this wide green meadow. We were of the earth, the sky, the trees, the hills. There was no telling where the world began and we ended.

As we walked back, her head low, my hands off the reins, I gently scratched her withers in love and congratulation, and I thought about all the things this great professor teaches me.

There were two huge lessons. The first is: everything is my responsibility. Mares have different moods and off days and mornings when they get out of bed on the wrong side, just as humans do. But if I am doing my job well, she will be well. I can’t blame her, or her high breeding, or her previous job. I can’t blame what is going on in the world. If I am right, she is right. My absolute number one job is to let her know, at every moment I am with her, that I have what it takes to keep her safe. Actions have consequences, one of the great rules of life.

There was a small sub-lesson in this one too, which is: you have to be dogged. Never give up. Don’t let discouragement whack you round the head. Keep on until you find that lovely shining note, on which to end.

And the second lesson was how I thought about that morning. I could have taken the negative from it. The rotten part was pretty rotten. We were both at our worst, for those horrid minutes. I could have seen this as a rank failure and castigated myself and decided all the work I have done so far was for nothing and I should not be allowed to keep a gerbil, let alone a thoroughbred. Instead, I decided to take heart from the beautiful parts.

There were two steps backwards, and I shall learn from those. But there were floating, dancing, magical steps forwards, and they cannot be sullied by what came before. They existed; they shine in my memory as I write this. Nobody can take those away from us.

And perhaps my last great lesson is a very simple one, which I should really know by now, but which I need to be reminded of, often. It is: if you want something lovely and fine and effortless, you have to strive. You have to practice. You have to be rigorous. It’s exactly like writing. Gleaming prose is not sent by the language gods. It is the result of daily struggle. If I want a soft and happy and light horse, I have one great tool at my disposal. It is free, and it is available to everyone. It is the most valuable bit of kit in any horsewoman’s box. It is: time.

Two quick pictures, after all that ridiculous prose -

After a hose-down and a damn good roll, she moseyed over with her Minnie the Moocher face to have one last scratch before I left her:

And then a very well-deserved drink:

Oh, that face. It never fails to make my heart sing.

July 7, 2014

Ordinariness.

I never wrote that book, in the end perhaps because it was too ordinary. In the end, perhaps, because the only answer is that you keep buggering on, and one really can’t make a whole book out of that. Some days one buggers better than others. Occasionally, the demons wrestle you to the floor, but you do not speak of that, especially if you are British. Even now, with the internet age and reality television, the default mode of the Ordinary Decent Britain is a sort of resigned and humorous stoicism. Worse things happen at sea.

My mother is in the hospital. It is not a grave ailment, but she is having a horrible time. I tell myself not to fret. The redoubtable stepfather travels in and out of Aberdeen, carrying on, making no fuss. I cook him breakfast. ‘You will need an egg,’ I say, seriously, ‘for strength.’ Then we discuss tribalism, and its discontents. We love a bit of geo-politics with our eggs.

I ride my horse and do my work and eat some fish for my brain.

My childish mind shouts: I want my mum to be better. My adult mind says, calmly: come along, better do the washing up and then take the dog for a walk.

Today’s pictures are two little photo essays, one of a happy horse, and one of a happy dog, who has a handsome new boyfriend:

As I finish this, an email pings into my inbox, with an update from a fellow blogger. I have met her in real life, and we are connected through mutual friends, but she is truly a blogging friend, a kindred spirit I met through this funny new medium. She has heartbreak because a gentleman she thought might be The One turned out not to be. (Reading between the lines, I suspect he has not quite behaved like a gentleman either.)

There is an ordinary grief for you. Every day, all over the world, people leave, and there is only a blank space where all the hopes and dreams were. Every day, women like my friend do exactly what she is doing which is: admit the pain, and bash on through it. Every day, there are good women downing a stiff gin, swearing a bit, reading themselves lectures on their own folly (it is always our own female fault, in the irrational mind), picking themselves up, dusting themselves off, and starting all over again.

My friend is doing this in a gloriously British way, with understatement and quiet courage. In fact, she is half Norwegian and lives in America and is really an International Woman of Mystery. But the good old British phlegm is there, even as she writes ravishing heartbroken prose, shining like a beacon, calling to me like across the ocean like a homing pigeon.