Tania Kindersley's Blog, page 15

November 17, 2016

Stuff.

There is stuff at the moment. Stuff, stuff, stuff. I didn’t write the blog for a couple of days because I did not really know what to say about the stuff. It’s the same old stuff and it’s quite catastrophically dull. Don’t tell them about the stupid stuff, says the stern voice in my head. They’ve all got stuff of their own; they don’t need to hear about yours.

I feel a bit stuck. I get stuck sometimes. I’m like a car whose gears don’t work. I’m in neutral, gunning my engine, going nowhere.

As always, when this happens, the one place where everything moves and flows and is good and right is on the back of my red mare. Her power and glory gives me strength. She does not get stuck. She moves out into the green world with her authentic mind and her athletic body and when we’ve done some good work she flutters her enchanting eyelashes and goes to sleep. She is at one with herself. I sometimes gaze at her in awe and wonder and try to work out how she does it. She is her own absolute self at every moment of every day.

Some of the best things I learnt about life, I learnt from this horse. I learnt about giving rather than demanding, about kindness rather than impatience, about concentration rather than showing off. I learnt the value of steadiness and consistency and clarity. I learnt about category errors. I learnt not to take out my messy emotions on her. My nonsense is my nonsense, and it is not her job to make that better. (Although of course she does, simply by being her fine self.)

I always think: why can’t you take that best self out of the field and apply it to humans? When I am with that horse, I am a far, far better thing. Then I get back to my desk and my ordinary life and I grow flawed and scratchy. My frailties flock back like homing pigeons, the little buggers.

Everyone has stuff, says my kind, rational, adult voice. Everyone deals with it in different ways. It’s not failure. You don’t have to shut yourself up in the Cupboard of Shame. You are human, that is all, and this is life, and there’s a supermoon and strange things going on in American politics and you still really, really miss your mum. You are not impervious, nor should you be.

At least, I think, I have that one true thing. Every day, for a couple of hours, I know what it is to give myself utterly to the happiness and well-being of someone else, even if she has four legs and does not speak English and cannot do abstract thought. This is not selfless, because the happier she is the better she goes and the more delight I feel on her grand back. But it is an offering, rather than a taking, and I find that oddly important and consoling.

I can write a sentence, I think. I know what to do with the language of Shakespeare and Milton. I have dancing, antic dogs. I have the hills and the trees. They will all endure, whilst the stupid stuff will pass.

Everybody has stuff. It’s in the contract. There’s no point in trying to fight it or getting bent out of shape or sitting furiously in a room attempting to think it away. Open yourself to it and let it run through you and know that soon, soon, it will sail out to sea, off to another port of call.

Published on November 17, 2016 06:36

November 14, 2016

Try for better things.

I snapped at someone today. I am very ashamed of myself. I did not say anything rude or unkind, but the tone of my voice was rough and impatient. I try so hard to be polite and I fear I was rude.

This horrid snapping voice tends to come when I am driven into the ditch. It’s a three strikes and you are out deal. I can take the first thing, I can grit my teeth at the second thing, but the third thing sends me into the rude voice. This is not a voice I want to have. It is not my voice, I always think; I am not that sharp, impatient person. Of course I am that person, on rare occasions. I can’t slide out of it so easily.

When you work a horse, you are always thinking about what it really going on. Did she leap in terror at that pheasant, or was it nothing to do with the absurd old bird at all? Had the worry been cooking for a while, and had you done nothing to let that worry out?

So, rather startled by my own flying pheasant, which was that horrid cross voice, I go back to see what was really going on.

Two things I really hate are being told what to do and negativity. Sometimes these come together, in a hideous pincer action, where unsolicited instructions are given in a voice of doom. I want to crawl away into a hole somewhere. I love the answer to be yes. Why not take a flier? Why not try that oddity? Why not cast out into the unknown? Well, say the doomy people, you can’t do that, or that, and that is going to be a problem, and that won’t work, and that’s a lot of nonsense. I am a lot of nonsense. I’m used to being a lot of nonsense. I’ve been nonsense for my entire life and it’s not going to change now. I sometimes can pretend to make perfect sense for short periods if I really concentrate, but nonsense and I are old, old friends. Mostly people laugh at this, kindly, not with too much mockery. Sometimes, they point it out ruthlessly and I feel all the air go out of my antic red balloon.

And because I am crushed and squished and crashed, I stomp my feet and use the horrid sharp voice, in instinctive defence.

But here is the thing. And I really do believe this. You can’t make other people do what you would love them to do. It is not their job to take care of your tender feelings. It’s lovely if they do, but those ones are your three best friends and you great-aunt Maud who understands everything. Most people are far too busy thinking about their own singed feelings and their own lost dreams and their own fragile desires to have much time to worry about your little three-act drama. So the snapping is not only unfair and rude, but irrational and pointless.

A small voice, deep in the recesses of my tangled brain, says: be the grown ups. Roll with the punches, says that voice. Know that you don’t always get what you want. Allow other humans to say what they say and think what they think and then carry on along your own primrose path. Wave and smile, says the wise voice, laughing a little. Every day is not Doris Day.

I called a friend after the terrible snapping incident and she laughed and sympathised and did not judge and disentangled the tangle with wisdom and grace and then told me such an excellent dog story that I almost fell off my horse. The red mare, who was practising for the Standing Still Olympics, flicked her ear back towards me, in easy pleasure. She adores the sound of human laughter.

There are always two choices, I thought, as I sent her into a rolling cowgirl canter. I can lash myself into a frenzy because I was ungracious and sharp, or I can see why it happened and use that knowledge to make it less likely in future. Knowledge is power, as I said to the vet today. I love going to the vet. We talk about Donald Trump as he examines my little brown mare and he understands that it breaks my heart that she is not right and he does not do the empirical dry scientific thing but allows space for emotion. It looks like we are not going to be able to fix her up as we had hoped, but are now in the stage of managing her condition. Although officially I am filled with purpose and hope for this new plan, perhaps I am sadder about that than I will allow. Perhaps that was partly why there was the sharp, snapping voice. Everything has a reason.

Humans are not perfect, I tell myself, sternly. They make mistakes and are not always their best selves. But they can try and hope for better things. That is my resolution of the day. Try for better things. It’s not splitting the atom, but it’s something.

Published on November 14, 2016 06:18

November 11, 2016

With the dead.

At 11am on the 11th of November 1918, the guns of the Great War fell silent. Almost one hundred years later, I sit on my red mare, looking out over the snowy hills. We are at the top of a small rise, on rough ground, a gnarled old oak on one side and a bright beech, glimmering with its autumn pomp, on another. The ground is covered in hoar frost and there is a slight hint of mist in the air, almost like gunsmoke.

At 11am on the 11th of November 1918, the guns of the Great War fell silent. Almost one hundred years later, I sit on my red mare, looking out over the snowy hills. We are at the top of a small rise, on rough ground, a gnarled old oak on one side and a bright beech, glimmering with its autumn pomp, on another. The ground is covered in hoar frost and there is a slight hint of mist in the air, almost like gunsmoke. The church bells toll the hour.

The mare and I stand very still. I think of the dead. They were once called the glorious dead, but there was nothing glorious about that carnage. I think of the frightened boys and the weary officers and the doctors desperately trying to put back together shattered bodies. I think of the war horses struggling through the mud and the pointless bayonet charges and the blind generals.

Remembrance comes to me in two waves, each year. On the 11th of November I think of the First World War. On Remembrance Sunday, I think of all the dead, as the veterans of every battle from El Alamein to Musa Qala march up Whitehall, smart and upright, medals blazing on their chests, a haunting mixture of pride and grief and regret on their stoical faces.

After two minutes, I look at my watch and stroke the mare’s strong neck and say: ‘Right. Back to the living.’

As we strike our way down the slope and across the wide meadow, still in the shadow of the hills, I think of my own dead. It is just over a year since my mother died. I’ve been missing her lately, so much that I sometimes can’t breathe. Grief works in hard tandem with time; the two trot along like trained carriage horses. Time is good and true, and gradually, kindly, pulls the lance from the side and gives the wound the air to heal. The scar remains. Sometimes, someone says something or does something that slices the top off, and the pain is so intense that it makes me gasp out loud. The missing never goes away, but it comes at intervals now. The bashed heart begins to understand that there can be true happiness alongside sorrow, that grief does not cancel joy, but can live with it. Everyone in the middle of their life discovers this truth. It’s a hard truth but a consoling truth.

Early this morning, as the bright frost glittered and the mercury hovered at minus three, I read that Leonard Cohen had died. Songs of Love and Hate was one of the first albums I ever heard, at the age of seven. It was a bit of a leap from Puff the Magic Dragon, but I made it. I fell in love and I never fell back out. Cohen went with me to school, through the lonely years when I got things wrong and never quite fitted in with the group. (I did not understand how groups worked, and was always transgressing unspoken rules and being hurled out without a word of warning.) He came with me to my first grand romance. It was a hopeless romance and it made me cry a lot, and crying to Cohen made me feel less alone. The album of those years was simply called Songs of Leonard Cohen, and I listened to ‘Hey, that’s no way to say goodbye’ over and over and felt that he was tracing the contours of my heart.

He came with me through my older years. He was there through all the heartbreaks, all the family dramas, all the funerals, all the knocks and blows and shocks. He was the old friend who did not say pull yourself together, or you should do this, or you are hopeless at that, or butch up, but said instead, I know just how you feel because I have been there too. That is a great gift.

So, this morning, I wept for him as I would weep for a friend. I cried because he was a gentle soul and a great poet. I cried because my mother loved him, rather surprisingly (her other favourites were Neil Diamond and Harry Nilsson and The Carpenters), and whenever someone put ‘Diamonds in the Mine’ on the record player her eyes would light up with mischief and she would sing along, because she knew all the words. I cried because another piece of my childhood has gone.

I’ve mourned many of the great old gentleman in the last couple of years – a godfather, a cousin, an uncle, my father’s best friend – all of that age, the ones born in the thirties, who remembered the war and knew what stoicism was, and wildness and romance too. As they go, one by one, gentle into that good night, I feel an acute sense of loss, as if someone is slowly dismantling a wonderful old building, so that its venerable stones litter the ground like fallen giants. I have to pick up those stones and build something new from them. I, like everyone my age, have to build my own building.

All morning, I was with the dead. I carried them with me like a weight, the ones I knew, the ones I did not. And then, when I said to my mare, ‘Back to the living’, she pricked her ears and stretched out her great, powerful, thoroughbred body, and struck out into the green fields, and she was so alive, so present, so authentic, that the weight lifted and light returned. When you are on a creature who lives on a different plane, who is so elemental, whose mysterious mind you can only barely touch, whose every instinct is different than yours, and when that creature gives you her consent, across the species barrier, there is something so visceral about it that it is like a distillation of living. It is very pure, and very beautiful. I feel that I am in partnership with something much greater and finer than I can ever be. And that extraordinary feeling banishes the shadows. The dead retreat, with a melancholy, long, withdrawing roar. I think of Matthew Arnold. Ah, love, let us be true to one another.

There is a scattering sound, as the bright scarlet leaves fall suddenly from the trees, surprised by the hard frost. The mare opens her eyes. The leaves are done, for this year. But in the spring, the tiny buds will appear as if by magic, and the stinging emerald leaves will fight their way out and unfurl in their canopies of green, and the world will be new again.

Published on November 11, 2016 05:04

November 9, 2016

Persuasion

I get on the telephone. I ring people up. ‘What the buggery just happened?’ we ask each other. Nobody knows. None of the conventional explanations seem quite enough. Was it the failure of capitalism? Was it the rise of social media? Did bloody Twittermake the difference?

‘All I hope,’ says one friend, ‘is that the poor Queen never has to sit next to him.’‘Yes,’ I say. ‘State banquets for anyone else. Bhutan, Estonia, the People’s Republic of Absolutely Anywhere.’ We contemplate the horror of Donald Trump sitting next to the Queen. Then we contemplate the horror of Donald Trump. We discuss the elements of narcissism. It is such a doleful list.

After a while, I give up. I can’t read the news. It’s like one of those awful, nihilistic, purposely shocking novels that you’ve always avoided because you don’t want to sear your eyes with such shoddy prose. I read Persuasion instead, for the twentieth time. I need manners. I need wit and delicacy and good-heartedness and truth and a happy ending. I need sweet, kind Anne Elliot and dashing, adoring Captain Wentworth.

In the gloaming, down at the horse’s field, the good, quiet, trusting creatures eat their evening hay. I shake it into perfect piles for them and they breathe contentedly through their noses. An indigo mist is rising and a hunter’s moon sails, amber and serene, in a mauve sky. Everything is very real. The dogs dance and play, antic silhouettes in the fading light.

I think of the things one cannot change. Away across an ocean, a great country has been gatecrashed by a man of no mind, no manners and no morals. ‘America,’ I had said this morning, ‘gave us jazz and Dorothy Parker and Scott Fitzgerald and Hollywood and the Algonquin Round Table and Louis Armstrong, and now it gives us this.’

I wonder: will the world change? Perhaps the shock of the vulgar will make the good people, the brave people, the clever people stand up and do something magnificent. Perhaps, this time in four years, Elizabeth Warren, who is a real revolutionary instead of a fake one, who is a real femme du peuple instead of a prancing poseur, who is a proper human being instead of an empty suit, will be swept to power on a tide of relief. Perhaps the grown-ups will be the grown-ups. Swagger and bombast can only go so far.

I turn back to my book. ‘I hate to hear you talk about all women as if they were fine ladies instead of rational creatures. None of us want to be in calm waters all our lives.’ I think: I would not mind some calm waters.

Published on November 09, 2016 09:39

November 8, 2016

That is what a friend can do.

Yesterday, I was so bent out of shape that I could not even write the blog. I had a tipping point, and I fell into the abyss. In 77 Ways, I write a whole chapter about the tipping point. I was really proud of this because it was my own idea. I did not pinch it from the Wise People. I thought it up all by myself. It’s about that thing when one tiny remark, one minuscule set-back, one minor disaster can send you spinning out into space. You don’t think: ah well, the dog crapped on the floor. You think: this is the end of everything and I can’t cope and it’s all gone to hell.

I decided that if you could understand about your tipping point, you could head it off at the pass. You could look for the warning signs and start to protect yourself. You could eat more green soup, take more iron tonic, get more sleep. You could at once recognise when you were treading into the danger zone.

Theory and practice, my darlings. Theory and practice. My theory is so good. My practice is a constant embarrassment.

So I sat at my desk with my face set and my teeth gritted and a weight pressing on my head, unable even to type.

Today, the sun came out and the land looked pretty again and I felt the vague stirrings of ordinary humanity. I was no longer entirely a wreck. My friend was at the field, looking after her Paint, and I told her the whole sorry story. She did not fix anything or give me words of wisdom, although she is very wise, or tell me what was going on. She listened and nodded and understood. Two other people were involved in the tipping point, and she knew at once what was going on with them. So we sorted that out and then we galloped off into the steppes of human mystery. We talked about societal expectations and gender difference and the intricate psychology of marriage and why it is that some friends just get you and some don’t; we talked about displacement and category errors (my favourite subject) and children and literature and how life works when you are a bit different.

We talked about everything. We shook out the whole bag of tricks and scattered them on the floor and sifted through them.

This all took quite a long time. She was late for her life, by the time we had finished. She looked at her watch and said, rather ruefully, ‘I haven’t done anything today.’

‘Well,’ I said, ‘you have taken a great big sword out of my side, so that’s not quite nothing.’

‘Thank you,’ I said, waving as I drove off, ‘for restoring my sanity.’

That is what a friend can do.

It’s sort of a miracle really. You feel like crap and you feel a bit ashamed about feeling like crap and you crossly refuse to do anything about the crap and then a kind person with a sympathetic heart listens and talks and laughs and does not run away screaming and all the crap fades away as if it had never existed in the first place.

The red mare ate her breakfast with a secret, glimmering glint in her eye, as if to say: ‘those two old humans do love to talk.’ The great horseman who sold her to me is married to my oldest friend. He always says, with an equal glimmering glint, when I arrive in the south: ‘So, you’ll start talking the moment you get out of the car and you two will still be talking when you get back in the car to drive away.’ And it is true, because the power of those words is beyond price, beyond adjectives, almost beyond imagination. That talking, which makes people laugh, has kept me standing upright for thirty years. Here, in Scotland, the daily paddock therapy, as we call it, is the restoration to sanity.

I crave solititude. I live alone and I like doing things alone and I have a stupid pride in being independent. But you can’t do everything alone. Sometimes, when the tipping point comes and it all goes to hell in a handcart and you find yourself staring into the void, you need the incomparable balm of another human who really, really gets it. And they take you and put you back together, very gently, piece by piece, and you walk away and think: how did they do that? And: isn't it lovely that they can do that, and they take the time to do that, and they know exactly how to do that? Somehow, with kindness and thought and wisdom and humanity, they give you back to yourself. That is what friends can do.

Published on November 08, 2016 04:04

November 4, 2016

Love.

For a moment, my life grows complicated. I look at the complication and think I can make this as Byzantine or as straightforward as I want. I can tie the knots tight, or untangle them and let them loose. There is a choice. Life isn’t just what happens to you, it is what you think about what happens to you.

I ring up the Beloved Cousin, my oldest and dearest friend, the one who has been with me in the trenches for thirty years. I can’t tell you how many complications we have been through together. There was one spring where we seemed to do nothing but go to funerals.

I ring her up and she listens to everything and then she gives her words of wisdom. She is all Occam’s Razor now, as she grows older and more and more sage. She slashes through a problem or a sadness or a tangle with wit and brio. Then we talk about Jane Austen and Trollope and shout with laughter about a joke which only we can understand.

I thank her. ‘I could not have got through this year without you,’ I say. This is factually correct and literally true. I try to explain it a bit. I say: ‘It’s having someone you can ring up when you are at your worst and you know that they won’t judge and they will listen and they won’t tell you what to do and they will make a joke at just the right moment. It’s that thing,’ I say, ‘of not having to explain yourself, because you know the person gets it.’ We mull this over. ‘I’m not sure,’ I say, ‘that everyone has someone like that and I don’t take it for granted.’

In the spirit of simplicity, and in homage to the Small Things, I do a very small thing for a very magnificent person. I collect together some photographs of the magnificent person doing a magnificent thing, and I edit them and make them as good as I can get them, and I send them to her. She sends a message at once, of charming thanks. It really was a small thing; it took half an hour of my time. But it ended up having a big effect. ‘I will treasure those pictures and memories for ever,’ she wrote. I felt ridiculously tearful.

The funny thing is that I suddenly realised I was taking my own advice. I don’t do this nearly as often as I would like. In Seventy-Seven Ways, I wrote that when you feel emptied out, finished, beaten, the way to get yourself back is to do something for someone else. I completely made up this theory from some sticky-back plastic and one of Mum’s old Fairy Liquid bottles. (This is a Blue Peter joke that only Britons over forty will understand.) I did do some research for this book and found some nice empirical ideas that have studies and proofs behind them. But in some chapters I let my own flaky notions off the lead. This was one of those chapters. I decided that when you think you’ve got nothing left to give, you should give something. And it reminds you that the human spirit is infinite and that is a very comforting thought indeed.

I’ve had a long week and there are those horrid complications and I’m missing my mother a lot and I feel a bit beaten. And, in a very, very small and humble way, I did give something and the magnificent person gave right back and I’m going into this dark, wet Friday night with a song in my heart instead of a weight on my head. My flaky theory really did work. I’m more pleased and more surprised than I can say.

Ring up your best friend and tell her why you love her. Think about someone else instead of yourself, just for half an hour. Give something when you have nothing left to give. I have to keep writing these things down because I forget them, when the tangles come. My Occam’s Razor is sometimes rusty and blunt instead of shining and bright.

Love does it, in the end. All these small things are about love. Love and trees, my darlings; love and trees. And you’ll be all right.

Published on November 04, 2016 11:34

November 3, 2016

I damn well choose.

I get one of those telephone calls which is like a blow to the heart. It contains, at second-hand, carelessnesses and unkindnesses from someone I hoped might be careful and kind. The darts sting into their soft target, so that I can almost hear them as they fly through the air. The poor messenger is awkward and apologetic. I don’t shoot the messenger because I never saw the point of that. ‘Poor you,’ I say, telephone tucked under one ear, kneeling in the mud as I anoint the wound of my little brown mare. I wish, slightly ironically, that my own wounds could be cured with a bit of Manuka honey.

After you lose someone you love, your skin is thin as paper for quite a long time. You look normal on the outside, but you are not normal. You have been stripped of a protective layer and you have no defences. Rather as if you were recuperating from a long illness, you have to give yourself metaphorical beef tea and bed rest.

So I have no defences for this. I feel sad and battered and bruised.

I trudge back from the field, in the rain. In the kitchen, I make soup and voices on the radio talk about Brexit and the high courts. I feel myself falling down the rabbit hole of sadness and regret.

Then I think: you have a choice. I love the power of binary choice. In 77 Ways, I devote an entire chapter to binary choice.

So I tell myself that I can be sad and woeful and doleful and miserable, if I want to. That is absolutely allowed and possibly the correct response. If something sad happens, one should probably feel sad. Or, I tell myself, I can eat my soup and let the thing go and stop being tragic and read Pride and Prejudice for the ninth time. (Jane Austen is like my rock in a stormy sea.)

I choose soup and Austen.

I choose.

I damn well choose.

It’s not quite as simple as that, but it’s nearly as simple as that.

Published on November 03, 2016 10:48

November 2, 2016

The unsung.

Sometimes I see things which are not small, which must be written down, which must be remembered. I think: I want to put this in my memory box and have it always. (I sometimes wonder what this blog is for; now I think it is that memory box, where the precious things can live.)

Today, I saw one of those things.

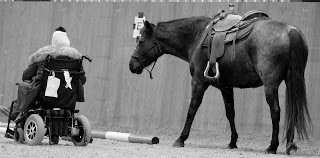

Up at HorseBack, a young girl was working a horse. Nothing especially wonderful in that, you might say. Except that this particular girl had been in a car crash that induced catastrophic brain and body injuries, so that her life would never be the same. She was going to be a jockey, had graduated from racing school, and then, in seconds, all that future was taken away.

I’m pretty good now with people who have parts missing. I used not to know where to look when I met someone who had no legs or no fingers or no arm or no eye. For God’s sake, shouted my British, embarrassed voice, don’t mention the war. Now I’m so used to it that sometimes I literally don’t notice. But someone in a chair is a whole other order of magnitude. I don’t know why it is different, but it is. I feel myself putting on the pity face, and the pity face is the last thing in the world that anybody wants. The thought of not being able to do everything for myself is my own greatest fear, and I am projecting that onto the chair-bound person.

The interesting thing is that this lasts for about five minutes. I can’t seem to stop myself doing it at the very start, but, before long, the chair fades into the background and the human comes into sharp focus. That human might have a body that has been wrecked, and a brain that has been battered, but they still have their character and their spirit and their idiosyncrasies. Once I get that, I can put the stupid pity face away.

This girl worked a sweet little mare on the ground. The mare is called Ellie-May, and she is one of the kindest horses at HorseBack. She is universally beloved and very well trained, but she is not a trick pony. Nobody taught her to follow a motorised chair, and at first she would not do it. The human had to have some skills. She had to gain Ellie’s trust and empathise with the equine mind and send out signals which the horse would believe. Undaunted, she did all that, and then the mare followed her accurately through a fairly complex obstacle course.

‘I can’t believe she just did that,’ I said. It was a raw, cold day, but I felt as if I were standing in shafts of sunlight.

Perhaps the most wonderful thing was the girl’s mother. I can’t imagine what it would feel like if you see something like this happen to your beloved child. I can’t imagine what you do with all those hopes and dreams you had for that child. I can’t imagine how your heart must break for that child. Yet this mother was making jokes. She made me laugh so much that I had to be asked to be quiet, since I was distracting the horse. The mother not only was full of merriment, but she made jokes about her daughter’s physiotherapy, and told me of the teases they have together. There was not a trace of regret or self-pity.

What strength, I thought in awe, some people have. There are so many unsung people. They are not film stars or famous footballers or prime-time politicians; they grace no magazine covers and win no prizes. They mostly don’t have much money and they have no fame. But there they are, unbowed, getting on with it, making jokes about something which should not really be that funny. They are the kings and queens of the human spirit, but they wear no crown and demand no protocol. They remind me that, whatever happens, one should never give up.

And that was why I wanted to remember, to write it down, to put it safe in the box. That is a memory to keep.

Published on November 02, 2016 10:22

November 1, 2016

The man of my dreams.

The sun shines like a proper, blazing thing. It shines so hard that it cuts through the hard cold of the frosty night and brings warmth and life to the field.

The sun shines like a proper, blazing thing. It shines so hard that it cuts through the hard cold of the frosty night and brings warmth and life to the field.I ride the red mare. Three weeks ago I had a massive sciatica attack after my piriformis muscle went into wild spasm. The clever doc fixed me up and gave me the good drugs but ever since I’ve been feeling as if I had been in a bar fight.

Today, I think, is the day to butch up and get back in the saddle. I decide sensibly that I’ll just get on and have a little walk.

We have a little walk. Ah, I think, I am home. This is where I live. The mare feels so soft and happy in herself that I let her roll into a canter, and she gives me her best cowgirl canter, her Green Grass of Wyoming canter, so I only have to keep a fingertip on the rein and I can scan the horizon for all those imaginary cows that must be rounded up.

I’m back, I think.

Fired with achievement, I ring the AA. The day before the piriformis went nuts, I had driven my car into a hitherto unperceived block of granite and ripped one tyre to pieces. Because of the bar fight, I had not had the strength to deal with it. Besides, there is always the terrible embarrassing moment when I have to admit to the AA that I am fifty years old and I can’t change a tyre. I will put off that moment for any money.

The man on the telephone is enchanting, and laughs at my feeble jokes. ‘What we’re here for,’ he says, with happy sincerity. ‘You might as well give us a job to do.’

And in an hour flat the mobile goes and a voice says: ‘I’m Martin from the AA.’‘Martin,’ I say with joy, ‘you are my dream man.’Martin takes this on the chin.I am not exaggerating. At this point in my life, the man of my dreams is one who pitches up with an implement and gets me back on the road.

He gets out his special implement and in two minutes the tyre is changed. The little brown mare wanders up to say hello. I assume this will be a great treat for Martin, and introduce him. He looks faintly dubious, but hides any doubt behind perfect politeness. I tell him about thoroughbreds and how my dad rode in the Grand National. Sometimes, when I veer off onto tangents like this, I catch the flicker of fear in people’s eyes. Not in the eyes of the AA. Martin is a warrior of the road and it would take more than a woman with crazy hair and old horse stories to alarm him.

My kind friend then follows me to the garage so I can drop off the car to get the temporary tyre switched for a proper one and sweetly drives me home. As I get out, she says something so funny that I stand in the drive for three minutes, immobilised with laughter.

The sun goes on shining as I edit 82 pages. Cut, cut, cut, shout the voices in my head. I am warring with the weakness of self-indulgence. There are passages I love, but I know they must go. I stare dubiously at the dead darlings file. I really don’t enjoy this process. When it is over, I feel as exhausted as if I have been working in a factory. I mock myself for this. You are really not putting in rivets on an assembly line, I tell myself sternly. But the stretched brain has had it, and snaps into uselessness.

It was a good day. I’m glad I wrote down this day. It was filled with very, very small things, but they glittered and gleamed in the sun like jewels. They meant nothing to anyone else, but they meant a lot to me. The red mare was mighty, the AA was kind, the good friend was funny, the manuscript was polished. The poor old car, which had stood so forlornly in the field that it actually began growing grass under the windscreen wipers, is now in the safe hands of the garage and will be fixed. Things got done. That, in my book, is a day.

Published on November 01, 2016 08:57

October 31, 2016

In which I am in dire need of imaginary cows.

It is a gloomy Monday with surly rain falling from a sky the colour of disappointed pigeons. A cross voice in my head says: don’t write the buggery blog. You won’t have anything lovely to say, says the cross voice, so don’t say anything.

Oh, says a sterner voice, write five sentences and even if they are absolute crap you have still recorded your day.

‘Why do I need to record my day?’ I ask the stern voice.

The stern voice considers.

‘Because even on a rainy Monday there will be one good thing,’ it says.

The farrier came. That is a good thing, because she is young and wryly funny and good at her job. I love people who are good at their jobs. The horses now have neatly trimmed hooves. Their frogs have been inspected and pronounced tremendous. I have horses with tremendous frogs. This, I think, still quite grumpy, is not nothing.

I do 80 pages of editing. I loathe editing. But I suppose at least there are words to edit. There is a whole novel to edit. One day, if I work hard enough and the wind is coming from the right direction, that story might even end up in a bookshop. ‘Oh,’ someone will say to someone, taking it down from the shelf, ‘that looks like it might be interesting.’

I make green soup. Any day that has green soup in it is not lost. As I make the green soup, quite crossly, I remember that I did find a baby bison on Facebook this morning. In fact it turned out to be a baby musk ox, but it was very sweet. A small, adorable, woolly mammal can lift a rainy heart, even for ten minutes.

Then I made some chocolate fridge cake in case the Halloween children come. I loathe Halloween, but even I can’t stare at the small people with basilisk eyes and tell them to go home and eat broccoli. I don’t like sweets and don’t have any in the house, so I make the chocolate fridge cake. (Dark chocolate, butter, honey, almonds, goji berries. It’s the kind of thing that grown-ups wish children would like and the children have to look tragically polite whilst wishing that there was a lifetime supply of those disgusting chewy things in neon green. But it’s the best I can do.)

I think of yesterday, which was lovely. The sun shone and my friend Isla came to ride the red mare and they did beautiful cantering together whilst I shouted ‘Green grass of Wyoming,’ at the top of my voice. This is my idea of teaching riding. As they go into the canter, I bellow: ‘Open everything up. Open your shoulders, open your mind. Green grass of Wyoming, wild plains of Montana, imaginary cows. Go and round up those imaginary cows. Open, open, open.’ Then I think of the proper riding teachers. I double up with laughter. ‘I don’t expect that is what Mrs B tells you,’ I bawl, hysterical with mirth. But the funny thing is that the incredible rider does open her mind and think of the imaginary cows and the red mare senses it and extends her body and lengthens her pace so that she is rocking and rolling. Buck Brannaman always says, when a horse does something delightful, 'there's the change.' There was the change, even if it did not come about from the orthodox.

‘That girl,’ says my friend with the Paint, as we stand in the doleful field in the doleful rain in the doleful afternoon, ‘has an incredible seat.’‘Yes,’ I say. ‘She most certainly does.’I feel very pleased about the incredible seat.

Open your mind, I tell myself. Imaginary cows. So what if the rain is falling?

Published on October 31, 2016 09:59