Laura Kalpakian's Blog, page 3

March 16, 2022

The Great Timetable

Some ten years ago when Biblical-style rains pelted Western Washington, our basement flooded. In the yucky aftermath, I was obliged to wade through my family’s past which had been deposited there after my parents sold their house. Everything salvageable—boxes and bags of largely unmarked Whatever—I moved to the second floor, filling up a space that had once served as a toy room for my sons. Untouched ever since.

Then, last month, flailing through this stuff on an unrelated mission, I came, to my surprise, upon a box of photographs and memorabilia from my father’s family. I was especially happy to find again the photo of my Mormon grandfather, Will Johnson, posing in 1908, for his graduation from Ricks Academy in Rexburg, Idaho.

Then, last month, flailing through this stuff on an unrelated mission, I came, to my surprise, upon a box of photographs and memorabilia from my father’s family. I was especially happy to find again the photo of my Mormon grandfather, Will Johnson, posing in 1908, for his graduation from Ricks Academy in Rexburg, Idaho.

Founded in 1887 as a school for Latter-day Saint children, Ricks Academy later became Ricks College, offering Associate degrees. Will Johnson went there at the age of nineteen in 1906 because an uncle by marriage, Howard Hale, had become a new faculty member. Howard Hale prevailed upon Will’s parents to let him leave the farm and accompany him to Ricks for an education. Probably they let Will go because he was the eldest of five sons, and the other four could still work the farm. A family photo taken in front of their brick house in 1899, when Will was twelve, shows everyone in ragged, holey, half-patched clothes.

The young man in this studio photo, by contrast, is wearing a suit, a vest, a tie, a stiff collar and stiff cuffs. He has been posed beside artfully arranged flowers. He is a serious, unsmiling young man, his expression a mix of trepidation and pride. A bowler hat is perched upon his knee, as though immediately following this session, he will put the hat on, and dash out into the great world.

On the back of this studio photo, an inscription caught my eye, an inscription I had never before noticed. Faded words, visible only with a magnifying glass, read:

W.A. Johnson Jr.

May 22nd 1908 at Eighth Grade Commencement

age 21

George Johnson

This inscription, signed by Will’s brother George, shed a whole new light on my estimation of my grandfather. Before this moment I thought Will Johnson had faked graduation, in short, lied about it.

In this assessment I was hasty, and probably ungenerous.

I thought this because some years ago, readying a retrospective for my dad’s 90th birthday, I wrote to Ricks’ alumni office, and inquired after my grandfather as well. They had no record of William A. Johnson whatever. (They did have records of Howard Hale as a faculty member.) Ah, I thought at the time: Will Johnson had this picture taken to suggest graduation rather than document it. I repeated this judgment in the Johnson chapter of The Unruly Past: Memoirs (2021). In this assessment I was hasty, and probably ungenerous. Because Will had gone to Ricks at age nineteen, I assumed he must surely have already got beyond the eighth grade. I was wrong. He was twenty-one, a grown man, before he accomplished what he ought to have done by fourteen.

In the photograph there’s a tension in the way he holds the rolled-up, ribbon-tied diploma, as if he might use it to slash a path through the world, but none of Will Johnson’s many occupations were lucrative. He married in 1914, and over the years he taught in one room schools, he homesteaded, he dry-farmed; he worked in the sugar beet factory, and as a carpenter, house painter, mechanic. The family lived in hardscrabble, dismal poverty in Fremont County, Idaho. Later he, his wife and five children moved to Coeur d’Alene where, among other things, he taught naturalization classes for immigrants. At the end of his life in 1956 Will was a draftsman at Hill Field near Ogden, Utah. Where had he acquired drafting skills? Not from any school. He had taught himself through an endeavor that absorbed his whole adult life.

Will began this work in 1906 when he hadn’t even finished the eighth grade.

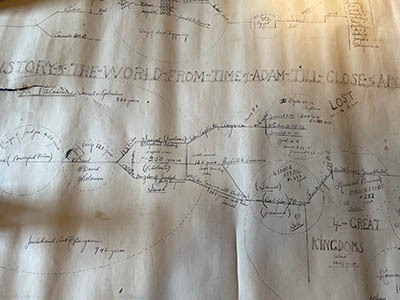

Will Johnson was a devout Mormon; the very core of his being was rooted in the church which he served in many capacities. But his most ambitious endeavor on behalf of his faith was “A History of the World from the Time of Adam to the Close of the Apostles’ Time,” a Great Timetable reconciling Biblical history, secular history and the history portrayed in the Book of Mormon. According to Howard Hale’s fulsome eulogy at his funeral, Will began this work at Ricks in 1906 when he hadn’t even finished the eighth grade.

Over decades, on long, furled painstaking blueprint charts and hand-drawn maps, he aligned these corresponding events, each year calibrated to a fraction of an inch. He drew a large, fanciful depiction of the woman mentioned in Revelations 12, the one with the sun and the moon under her feet, the one beset by dragons. The mind boggles at the research that went into this enterprise, to say nothing of the attention to detail. One slip of the pen, and he had to start anew—something that happened often because at his death in 1956 there were many such charts rolled up and stored in long cardboard tubes. These tubes came to my dad.

Over decades, on long, furled painstaking blueprint charts and hand-drawn maps, he aligned these corresponding events, each year calibrated to a fraction of an inch. He drew a large, fanciful depiction of the woman mentioned in Revelations 12, the one with the sun and the moon under her feet, the one beset by dragons. The mind boggles at the research that went into this enterprise, to say nothing of the attention to detail. One slip of the pen, and he had to start anew—something that happened often because at his death in 1956 there were many such charts rolled up and stored in long cardboard tubes. These tubes came to my dad.

Last month, having found the graduation picture, I poked among the boxes and bags in the former toy room, and found them. I took them downstairs, opened the tubes, unrolling the charts for the first time since 1978 when my dad had let me take them as research for These Latter Days.

I marveled at the precision, the ambition, the dedication.

Some tubes contained several versions, each six or eight or ten feet long, mostly white ink on blue paper. A very few were dated, 1945, 1950, none designated as the final. I marveled all over again at the precision, at the ambition, at the dedication that informed this whole undertaking. Unrolling these Great Timetables on which he so labored, re-assessing his life, I was moved to fresh respect for Will Johnson.

When I die what will happen to these Great Timetables?

I am older now than Will was when he died. Old enough, certainly to recognize a lifetime’s commitment to creating and expressing one’s deeply held convictions. I asked myself: when I die what will happen to these Great Timetables? None of my family has any connection with the Mormon church, nor any contact with whatever is left of the huge Johnson clan. In the back of my mind, I kept hearing Orson Welles’ breathy “Rosebud” as the sled was flung into the fiery furnace. The older I get, the more poignant is that moment.

Ricks College is now BYU-Idaho. I wrote to the Special Collections librarian there with backgrounds on the Great Timetables, and the fifty years of labor they represented. I offered to donate them to the place that had first inspired Will. To my delight, the librarian replied that they would happily accept.

In truth, I had no special affection, or even much recollection of Will Johnson, but in sending his work to BYU-Idaho’s library, I felt a flush of gratitude toward him. Perhaps from him I inherited the perseverance to pursue an evolving work for decades. I was glad I could honor his commitment and his memory, and redeem, in some way, those long, no doubt lonely hours he poured over these rippling blue sheets of carefully calibrated time.

The post The Great Timetable appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

November 2, 2021

Destiny’s Consolation Prize, or “Forget Domani”

“Hi,” I said, laughing out loud, “and I’m Virginia Woolf!”

I always try to keep a bottle of champagne in the fridge just in case there should suddenly arrive a day worth celebrating. Finishing a book, for instance that’s worth celebrating (although “finish” turns out to be a relative term; I have “finished” the same book many times over.) Selling the book to a publisher! Celebrate. The arrival of the contract. The arrival of the advance. The arrival of the ARCs or bound galleys. The actual first copy to hold in your hand, proof that at last your amorphous idea has become actual artifact. Celebrate!

So I was prepared last week when the University of New Mexico Press sent me this picture the brand new Memory into Memoir in the window of the Harvard Book Store. I’m told the book will remain there till November 7th. Like a member of a renowned choir, Memory into Memoir glows among fine company. This photo sparked for me the memory of my 1998 interview at Harvard for the position of the Briggs Copeland Lectureship, one of four finalists.

I pictured Helen Vendler in her study, surrounded by ten thousand books, nine hundred of which she had written

I saw the Briggs Copeland Lectureship (basically Writer in Residence for a finite four years) advertised on a national job-listing subscription. I trotted out the usual letter I used in my yearly rash of applications. (Rash is the correct word.) In support of my candidacy I sent my brand new novel, Caveat, the best novel I had ever published (probably still true). Taut, intense, uniquely structured, thematically ambitious, full of character and rich with voice, Caveat is a novel of rain, greed and revenge in Southern California. I assumed the book basically was a donation to Widener Library; I didn’t have a chance at the job.

A few months later my youngest son called down the basement stairs where I was sorting through a pile of dirty clothes. He said the phone was for me. I picked up the extension and the voice said, “This is Helen Vendler calling,”

“Hi,” I said, laughing out loud, “and I’m Virginia Woolf!” But even as these words crossed my lips, I thought, yes I have a lot of literary friends, but why would someone say Helen Vendler?

And then Helen Vendler, the world-renowned literary critic said something about an interview at Harvard University and the Briggs Copeland Lectureship.

I pictured Helen in her study, surrounded by ten thousand books, nine hundred of which she had written. I dropped the dirty shirt in my hand.

I could belong here kept chiming in my head

A few weeks later I flew to Boston and thence made my way to Cambridge where the Harvard English Department put me up in a fine hotel adjacent to, maybe even on the grounds of, the university. The charming, bright yellow Longfellow House stood nearby with its 19th century air of prim, academic contentment. I looked at it longingly, and thought, I could be here; I could belong here.

The interview was the very next morning. I had been gnashing with anxiety for weeks. How to portray myself? Solemn? World-weary? Lively? Energetic. Oh, but not too energetic… on and on. I walked to the English department on that fine, crisp early-winter morning, and climbed the paneled stairs. I could belong here kept chiming in my head as I met with Ms. Vendler, with the John P. Marquand Professor of English, Laurence Buell, and the poet, Jorie Graham. The air, shall we say, was thick with poets—poets, not simply present, but past since both Ms. Vendler and Mr. Buell had literally Written the Book on famous poets. Oh, and Seamus Heaney was probably teaching a class down the hall at that very moment. I could belong here.

“I bet I am the first girl from St. Elmo California ever to sit in this room.”

We met in a large seminar room paneled in rich wood with high windows splashing pale sunshine across the intricate, antique carpet. They introduced themselves (as if they needed introductions) and served coffee in china cups with the Harvard insignia. I kept thinking of my character, Rica Benn in the novella Dark Continent. In 1910 Rica is a guest at a dinner party at some lordly English manor. She remarks wistfully to crusty old Sir Rupert seated beside her, “I bet I am the first girl from St. Elmo California ever to sit in this room.” (To which her unimpressed companion replies, “A dubious honor, madam.”)

On these hallowed Harvard walls hung heavy-framed portraits of past worthies, among them Mr. Briggs and Mr. Copeland. I know this because although I was too nervous to remember anything at all about my hour long conversation with the legendary Helen Vendler, and Ms. Graham (fresh from the pages of the New Yorker) and Mr. Buell, who might as well have been personal friends with Longfellow and Thoreau, at the end they asked: Did I have any questions for them?

Are there special chants, incantations I can drone? Or particular saints to pray to, lesser gods, perhaps? Are there smoky sacrifices needed to get this job? “Who were Briggs and Copeland?” I asked.

Ms. Vendler pointed to their portraits on the walls. She said that Briggs and Copeland had created this Lectureship to bring to the Harvard English department writers who might be the equivalent of “a bit of fresh air.” In short, someone who did not Be and Belong Here. That such a person might have some fresh perspectives for a four year appointment. I had fresh perspective radiating from my very eyeballs, I assured them on my way out.

O! To be part of a place where the past was present!

I walked all over campus afterwards, in high spirits. I felt like I was in a movie, confident I had struck the right notes in the interview. Next year I could belong here. I could have an office in the very building I had just left! Down the hall from Helen Vendler! Access to all the Harvard libraries and all their collections! (The thought made me giddy.) I could write letters on their lovely embossed stationery! O! To be part of a place where the past was present!

To be and belong to such a place, was a sort of girlhood dream. From the time I was a kid, I loved history, especially the 18th and 19th centuries. I loved historical fiction. I envied people who lived in houses with attics, who came from families with knowable pasts and deep roots with ancestors. For me, such a past could only be imagined. I had grown up in a neighborhood of tract houses, so raw, so recently replacing ripped-up alfalfa fields, so dry, that tumbleweeds still blew down the street in winter. Our public library was a storefront next to the Mode O Day dress shop. My high school classes met in uninsulated bungalows where the smog and heat rolled in, and all but sat down beside us. The university I attended was so new that the gray, block-like postwar buildings were set about with frail little trees staked with wires. And here I am! A Woman of the West, with the prospects of being and belonging at Harvard! Sashaying past the Widener Library among all these, smart, milling strangers who might be my students or colleagues. The future gleamed.

I don’t know who they hired. It wasn’t me.

I walked all over Cambridge that afternoon, loving the ambience that reminded me of Berkeley, a place that bristled with young people and ideas and high spirits. In the Harvard Bookstore I dropped a bunch of money. So much money on so many books that I had to have them shipped to my home in Washington. I also bought Harvard tee shirts for my entire tribe, though some inward voice whispered, If you don’t get the job, these might make you feel bad every time you…

I walked all over Cambridge that afternoon, loving the ambience that reminded me of Berkeley, a place that bristled with young people and ideas and high spirits. In the Harvard Bookstore I dropped a bunch of money. So much money on so many books that I had to have them shipped to my home in Washington. I also bought Harvard tee shirts for my entire tribe, though some inward voice whispered, If you don’t get the job, these might make you feel bad every time you…

I don’t know who they hired. It wasn’t me. Wasted anxiety, but not wasted effort. Before I met my dear friend Paola Rizzoli for dinner that night, Destiny’s Consolation Prize led me to one of those shops that time forgot, a funky, dusty, dim-lit used record store. My fave sort of place. I pawed among the musty bins of old LPs, and behold! Among other treasures, for $2.99 I found the soundtrack to The Yellow Rolls Royce. A long-forgotten film, perhaps but wonderful music by Riz Ortolani, especially its award winning “Forget Domani,” a song I had been humming for years because I didn’t know the lyrics, a song that roughly translates, forget tomorrow, “…let’s live for now, and anyhow, who needs domani?…”

I hand-carried The Yellow Rolls Royce home to Washington in case my luggage got lost. I put the LP on the turntable as soon as I came in the door. My youngest son smiled to hear it.

In 1998 not one of my novels or story collections was on the shelf at the Harvard Bookstore. I would have remembered. I would have offered to sign them. Ah well, one of my books is there now. On the shelf, and shining in the window, Memory into Memoir. And with these few thoughts, written here, I have accomplished just that.

*****

Paint Creek Press will reissue the novel Caveat in 2022. Memory into Memoir is available wherever books are sold, including Harvard.

The post Destiny’s Consolation Prize, or “Forget Domani” appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

October 28, 2021

THE WEED-STREWN LOT OF PLOT #5

Memory will not be restricted to the needs of memoir. Memory is not merely unruly, but anarchic.

The past is mercurial. The writer of memoir might think she has confined it to the page, even turned it into an actual book. But memory will not be restricted to the needs of narrative. Memory slips away, sprite-like, laughing, resistant to artful storytelling. Memory is not merely unruly, but anarchic.

The nonfiction writer must resist anarchy. Fiction is more malleable. The fiction writer can occasionally give into anarchy (especially in the interest of narrative energy, often aided by alcohol and fueled by delusion masquerading as conviction). Particularly with a third person narrator, fiction can shape-shift, wander off into uncharted territories. Not so for the writer of memoir who must cleave to the picketed, well-mown plots of narrative memoir, and ignore the weed-strewn lots of memory. Here in the Truly Unruly we wade through those weeds.

Amy Henderson had vanished from memory of her own sister, erased.

The photo above, briefly mentioned in my The Unruly Past, depicts the primly Edwardian family of my Mormon grandmother, Mae Henderson Johnson in about 1905. The Hendersons, English by birth, converted to the Latter-day Saints, and emigrated to Salt Lake City (and thence to Idaho) in about 1908. In this photo Mae (born 1896) looks to be about ten and Eva (born 1898) looks to be about eight. Behind them, an older sister, Amy (b. 1893) looks to be in her teens, as does the oldest brother, Archie (b. 1891).

When, in 1977, my great-aunt Eva put this photograph in my hands, she was nearly eighty, frail, widowed, and living alone in a tiny apartment in Ogden, Utah. My jaw dropped; I was stunned to see on my grandmother, Mae, [far left] the absolute replica of my own young face. Shocking. Moreover, an older sister so closely resembled my teenage self—only a lot sadder. I pointed to her, and asked who that was.

Eva seemed to strain remember. “My sister Amy,” she said at last.

“I never heard even heard of her.”

“She died young.”

That was all Eva could offer. She could not even remember when Amy had died or what of. I asked if Amy had married, but Eva could not remember that either. Amy Henderson had vanished from memory of her own sister, which is to say, erased, forever forgotten.

But the Mormons in general do not forget. Indeed, they are the Great Rememberers. Their passion for genealogy serves their religious beliefs, and their genealogical records are painstaking. My grandfather, Will Johnson, was a dedicated genealogist and at some point his handwritten records came to my father who had no use for or any interest in them. These big manila envelopes sat in my basement until it flooded in 2010 when (mercifully) they were among the materials not inundated by water. I opened them, and scanned through the charts my grandfather had created and annotated in his neat Spenserian hand. And there was Amy Henderson.

Amy Henderson had indeed married, someone named St. Clair in January 1916. No first name is given. (He is the only person in all these records to have no first name noted.) Amy would have been about twenty-five, elderly for a Mormon bride. By contrast, both her younger sisters married before she did. Mae married my grandfather in 1914, age eighteen. Eva, the youngest girl, married in 1915 at the age of seventeen.

Poor Amy, east of Kelly, north of Conrad, south of Jones.

Amy died of unspecified causes in November 1918, that is, at the end of the Great War (Armistice, November 11, 1918). Might Amy have been one of the early casualties of the Spanish Influenza that swept the world in 1919, killing millions? Would the Spanish Influenza have reached Idaho that early? My guess would be no. Did she perhaps die in childbirth? Nothing to so indicate. And yet, at the bottom of the page my grandfather wrote an odd, sad note:

“Amy Henderson St. Clair was buried at Nampa, Idaho in Kohler Lawn Cemetery. Sec B, lot 64, plot parcel 5. In 1955 no stone or marker remained to find it. Grave is located east of Kelly and between Lois Conrad on the North and Elizabeth Jones on the South. Grave space #4 still belongs to the family in the name of W. W. Henderson (est. $10 each space) Nampa City Records.”

Why did he write this? Did my grandfather think someone might want to go find poor Amy (east of Kelly, north of Conrad, south of Jones) to lay some sort of remembrance where there was not so much as a marker that she had died, much less that she had lived? Had Amy at age twenty-five perhaps run off with this No-First-Name St. Clair? Nampa is a railroad town near Boise. The Hendersons as a tribe had settled far from Boise, in and around Sugar City, Fremont County, Idaho. How had Amy met St. Clair? Was he a railroad man with a job in Nampa? As a married man he would not have been drafted when America declared war in 1917, so in all likelihood they were living together in Nampa when twenty-two months after the wedding she died.

Amy was buried in Plot #5. However, that plot belonged to a Henderson. Does that suggest that St. Clair was unable to pay to bury his wife? Perhaps unwilling. Perhaps not even present? Clearly the family absorbed the costs of her death. Presumably Amy had a Mormon funeral, and after those last words were spoken, people walked away and workers at the Kohler Lawn Cemetery filled in the grave. If someone—anyone—had paid for a stone, it certainly would have lasted till 1955. Though Hendersons still owned plot #4 in 1955, no one is buried there.

I wanted These Latter Days to rescue Amy Henderson from the crypt of oblivion.

When Eva gave me this photograph in 1977 I knew nothing of the above. I did not even know these genealogical tables existed. I only knew that Amy had “died young,” and that her sad eyes, set in a face so very like my own, haunted me.

I thanked Eva for the photograph and took it home to California where I embarked on the novel These Latter Days. In writing These Latter Days, the story of a fictional Mormon family, I wanted to rescue Amy Henderson from the crypt of oblivion.

I created an eldest daughter, Eden Douglass, born in 1890. Eden also dies young, but in an act of rebellion. Eden has ambitions that set her apart from her siblings who, for the most part, do not look beyond the Mormon church or the town of St. Elmo, California. Eden has visions of travel and adventure, and though her actual plans are unformed, she has office skills; she has poise and personal insight, knowing that if she does not leave this smug, complacent town, her hopes and dreams, her very spirit, will wither and die. At twenty-one in 1911 she acts on these convictions. One rainy night she leaves home to take the eastbound train out of St. Elmo. Flood waters have undermined the foundations of the bridge going out of town; the bridge collapses underneath the weight of the train, killing everyone on board.

In my novel Eden does not lie in an unmarked grave. Her stone in the St. Elmo Cemetery has her name, her dates, 1890—1911, and at her mother’s request, one other chiseled word,

Regret

In my novel Eden Douglass is not forgotten. Her brother names his eldest daughter Eden Louise. She too escapes on an eastbound train. She goes on to have adventures (travel, danger, love affairs, marriage, children, heartbreak, all of which require her resilience) chronicled in These Latter Days and later, American Cookery.

[image error]Amy Henderson inspired me. As did Eva Henderson.

LK at ten years old.

Every time I look at this photograph I find the resemblance of Amy and Mae to my own young self deeply unsettling. Ironically I had no special affection or even respect for Mae Henderson Johnson. Perhaps unfairly I judged her to be dull, self-centered and without spirit. In any event Mae does not inform the pages of anything I have written (other than her appearance in The Unruly Past). But Amy Henderson inspired me. As did Eva Henderson.

On that same visit when Eva gave me the photograph she told the story of her own desperate flight from Idaho to escape her abusive first husband, the man she had married at seventeen. Taking her only child with her, Eva got on a train, keeping the little boy close, terrified that the husband might have discovered her absence, guessed where she’d gone, somehow got on the train, and was stalking the aisles looking for them. She feared he might snatch her back to the hell she had fled. Oh yes, there’s a story there. And I used it: the central act of the central character in These Latter Days, the lie at the root of her life, the lie that her eldest daughter, Eden, discerns just days before she takes that fateful train.

*****

These Latter Days and The Unruly Past are available in a new Paint Creek Press edition wherever books are sold.

The post THE WEED-STREWN LOT OF PLOT #5 appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

October 13, 2021

Passports and Visas

The past became like the creatures in Where the Wild Things Are, baring its terrible fangs, breathing its terrible breath.

“The past is a foreign country,” L. P. Hartley famously wrote, epigraph to his novel, The Go- Between. “They do things differently there.” The past, as it turns out, is a very messy country, lacking neat borders, beset with swamps and perils; the traveler clings to small chronological landmarks, the date of a wedding, perhaps, a death, a birth. This messy country is a jumble, most often a jumble of elation, contention, uncertainty, sometimes shock, sometimes boredom, weirdness, and wonder with tracts of happiness, and yes, misery. Anyone who has ever kept a diary knows that writing in the immediate present means that the trivial is larded in with the significant, the poor old diarist not knowing the difference while her pen scoots across the page. But the writer of memoir? Surely that person knows the difference! The memoir pulls the past into recognizable patterns, does it not? The writer of a memoir—of necessity—imposes narrative order over the unruly past. The writer of a memoir neatly arranges events that might, in the midst of living them, have seemed utterly unconnected, even chaotic. But that writer, or at least this writer, myself, did not take into account those irritating bits and shards of memory that refuse to conform to narrative needs.

After decades as a fiction writer, as I was writing a book of memoirs, I was astonished, even a little terrified to see that in wrestling my past to the page, it became like the creatures in Where the Wild Things Are. The past bared its terrible fangs, and breathed its terrible breath, and the writer in me recognized that the usual editorial/artistic tactics (write, edit, slice, paste, rewrite, rewrite again and move on) were unequal to this struggle. All this seething stuff must somehow be dealt with. But how?

The voracious nature of memory will not be satisfied with what you will cull for the picketed memoir. Yes, my book, The Unruly Past (Paint Creek Press, 2021) has memoir essays laid out in tidy chapters. But what about all the roiling undercurrents I evaded while constructing those chapters? All the material I avoided when pruning, tweezing memory into memoir? All that stuff I sliced off of my pages and out of my paragraphs because it raised more questions than it answered? It might not appear on the page, but it emerges nonetheless, tangled, chaotic, insistent.

I found that people who had not crossed my mind in decades began traipsing through my dreams. I woke in the night, stumbling on, recognizing strange, even eerie causalities, links in circumstances and with individuals that I only even noticed after I had made memoir out of memory. I was accosted by insistent voices, elusive scents, shafts of sudden light, sounds echoing just beyond the actually audible. I found myself wallowing in great vats of nostalgia for places I had lived and people I had once known. Not that those past places or people were uniformly happy experiences, quite the contrary, but I longed for the tastes and textures of those days. I longed to re-inhabit my younger self, the girl, the young adult who had no notion of the Finite, no notion that decisions she made with cavalier indifference would reverberate through her life for decades.

In writing fiction the pain can be off-loaded, siphoned on to characters who eventually take on a life of their own.

In his 1884 The Art of Fiction Henry James wrote “The novelist is one on whom nothing is lost.” I’ve taken this as mantra for my creative life, author of some seventeen books under my own name. Now, having written memoir, I know why I am a novelist. In writing fiction the pain can be off-loaded, siphoned on to characters who eventually take on a life of their own, and (in effect) give the author the finger while they go on to do whatever they please, quite autonomous, and free of the author, thank you. In memoir, the first person Narrator cannot do that. Whatever the pain, whatever elation, contention, uncertainty, shock, boredom, weirdness, and wonder, that experience will lead the writer—certainly it led this writer—to explore further truths, connections, messy overlays and underpinnings, whether I wanted to or not. When some random person nipped at my consciousness, when some long ago minor incident wafted across the page, of course I cut it from the memoir. But I found myself creating documents outside my working drafts; I gave these documents cryptic file names, and I spewed into them buckets of unlovely, exploratory prose.

Writing about the past brought me to my narrative knees.

I’ve often likened my process as a fiction writer to that of a solitary oyster rolling around some bit of irritating grit till finally he makes of it a pearl, or in my case, a novel or novella, or story. When I finish a novel, I often write up a “story behind the story,” just for myself, so I won’t forget the spark or germ that brought me to write in the first place. But once the novel is actually published, I do not return to it. Once it’s in print, I might leaf through the pages, even peruse a chapter or two, but I never re-read the whole book. Past novels seem to me like neighborhoods where I once dwelt and had my creative being, but I no longer live there. I’m always interested in the place, and the people, yes. I have affection for them, but I’ve moved away. I’ve left that neighborhood, that country.

But the memoir writer is not a solitary oyster. No, the memoir writer—throughout the writing process and indeed, after the book is finished—is beset with memory. Writing memoir I was accosted by the sad, knowing looks of people I once dismissed as dreary or unimportant, the jeers of people who lost patience with me, the sly smiles of people I had so admired who had disappointed me. Writing memoir, I could not clothe these people with new names and histories. I could not pop them into fiction’s kiln and take them out as fully-fledged characters. I was compelled to return to them, again and again, asking questions even if the answer is the hopelessly futile I don’t know I don’t know. Writing about the past brought me to my narrative knees.

To write about one’s own past means to visit that foreign country at one’s own peril. They do things differently there. You had better learn the language and shelter in place because the exit visa you so hoped for might not be easily granted.

The post Passports and Visas appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

September 20, 2021

M2M Unboxing Day #2

Memoir classes are especially poignant: the nature of the genre requires trust.

I have always been wrong about the amount of time I think any given book will take to write. I was wrong again about Memory into Memoir: a Handbook for Writers, just published by the University of New Mexico Press. When I put together the proposal in September of 2019, I confidently laid out the book using materials I have created and refined over decades of teaching a course called Memory into Memoir. I loved teaching this class, and I thought I would simply go through my teaching files, and put these materials in order to turn them into text. The work, I thought, would take six months. Tops.

University of New Mexico Press offered a contract based on that proposal. But as soon as I began to write, I realized I could not simply translate a class into a text. A class is a living, vital organism, and every person in that class—the quiet and the ebullient alike—contributes to the vat (you might say) that becomes the experience. Some classes have a particularly happy chemistry that has almost nothing to do with the instructor. Some do not. No two classes are alike. Memoir classes are especially poignant, much more so than fiction, because of the nature of the genre which involves, indeed which requires trust. Interactions in a memoir class are allied to—but not dependent on—the curriculum.

Each memoir class, that first night I always said to the students: “Look around at the people in this room. By the end of this three term class, some of the people here will be not just your fellow writers, but your dear friends. Some of you will see each other through crises; you will share your joys and support each other through sorrow. And why is that? Because you are here sharing your past. As much of the past as you care to share. Or as little. But you would not be here if you were not compelled, for whatever reason, to pin the past to the page.”

In these three hour, once-a-week classes I took care to foster connection and camaraderie beyond the reading and writing and creating. We always took a twenty minute break midway. That first night I always brought in snacks, and in the following weeks, people took turns bringing in snacks. Often these were simple Oreos or potato chips, but as the weeks passed, people sometimes contributed food that had been mentioned in their memoir, and so we got a taste of what that person had known. A writer who had family in the wilds of upstate Vermont shared fiddle leaf ferns that his nephew foraged and express mailed to him; he steamed them and brought them to class, a unique experience. One of my UW students was a sous chef at a posh Seattle restaurant. One of my students was a professional baker with her own booth at the Farmers’ Market. During these short breaks, people fanned out, talked, connected with one another, learned about each other in the present as well as in their pasts.

I wrote during that long Covid Aloneness, imagining phantom readers as if we were all in class together.

When I went to actually write the book created from my curriculum, I realized, suddenly, I would have to take an entirely new tactic. To put my material on the page in a way that was fresh and invitational, that would encourage readers though I lacked the interactions possible in the classroom. I needed to create a narrative and a narrative voice that was instructional, yes, but intimate at the same time, invitational. To say, in effect, Come with me. The book needed to be as much about the writer’s relationship to the past as to the writing itself.

Moreover, I wrote Memory Into Memoir during Covid, that great swath of time in which the pleasures of others’ company, of sharing laughter, experience, Oreos, was denied to all of us. For me, that long Aloneness was ameliorated by writing Memory Into Memoir, by imagining my phantom readers as if we were all in class together. As if, sans Oreos, I could still offer them a way to connect with their pasts, and, for that matter, to connect with me. I wanted the book to be unique in that regard.

I learned to infuse my own voice into the narrator’s voice on the page. The “I” here is in fact, moi.

University of New Mexico Press, like other university presses has a peer review process that commercial publishers do not follow. Once the manuscript has been turned in, the press sends it out to various other writers in the field to get their take on the merits, the viability of the book. These people reply with their thoughts and suggestions. One peer reviewer returned my book to the editor with something of dyspeptic harumph, words to the effect of this was not a real manual for writers; this was something else, though what that something else was…she could not exactly say.

Well, I am the author. So it is up to me to say, isn’t it? I added a Preface to clarify, to assure readers that yes, in fact this is not an Ikea How To manual. It doesn’t intend to be. Memory Into Memoir is an invitation to re-imagine the past in writing. To rethink, revisit memory in prose. To explore the process of placing narrative form over the unruly past. Putting what I know of writing about the past, putting all that into manuscript, meant giving it voice that can be actually heard on the page In doing so, I shared something of my own various pasts with readers, including bits and pieces of my other books and stories. I also shared something of my mother’s experience in writing her memoir. (Which she saw into print at the age of ninety-seven; Memory Into Memoir is dedicated to her.) The new preface closes inviting the reader to pick up the pen and to think of that pen as an oar as they paddle toward the past.

During the long Covid year in which I wrote this book and its companion volume, The Unruly Past: Memoirs (Paint Creek Press 2021) and though I am the author of many novels, I learned a lot about approaches to the past. Eye-opening. And I learned how to infuse my own voice into the narrator’s voice on the page. The “I” here is in fact, moi.

Early this summer many of the Covid restrictions lifted, and people began to gather anew. But now, September, when the author’s copies of Memory Into Memoir arrived here to be unboxed, I could only invite a few friends to my house to celebrate outside. The picture below conveys some of that festivity. And yes, the people in this picture are all writers I have met through my memoir classes, people with whom I have shared crises, joys and sorrows, laughter and pain over the years. Entirely fitting that they should be the present to open the box of the first copies of a book I hope will go into the world and connect more people in the present with their pasts.

The post M2M Unboxing Day #2 appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

August 23, 2021

The Unruly Past

All pasts are unruly. All pasts resist the tidy, codifying insistence of the page, resist the will of the writer.

When I was writing Memory Into Memoir (to be published October 2021) I chose to illustrate writerly concepts with passages, scenes and snippets from my many novels and stories. The University of New Mexico Press editor and other early UNMP readers reminded me that Memory Into Memoir is about writing nonfiction. I maintained (as I always have and always shall) that good writing is good writing, no matter the form.

In one of our Paint Creek  Press corporate board meetings (Zooming from our respective kitchens, wine glasses in hand) I mentioned to Andrea Gabriel, the CEO, that I had in fact published memoir essays in magazines, literary quarterlies and various anthologies. Andrea suggested, “Why don’t you collect them and we’ll put them in a book, and publish before Memory Into Memoir comes out! Then you’ll have a book of memoirs!”

Press corporate board meetings (Zooming from our respective kitchens, wine glasses in hand) I mentioned to Andrea Gabriel, the CEO, that I had in fact published memoir essays in magazines, literary quarterlies and various anthologies. Andrea suggested, “Why don’t you collect them and we’ll put them in a book, and publish before Memory Into Memoir comes out! Then you’ll have a book of memoirs!”

“Wow, what a good idea! I’ll do it! It won’t take long. I’ll just gather up what I’ve written before.”

Only. . . I discovered to my dismay that many of the memoir essays were from eras long past. They might have once been lively, but they were passé now. Others simply had not aged well. Others, especially those that had begun life as talks delivered at conferences, just wandered all over the place. Except for two short pieces, I trashed most of what I thought would go into the book. All the rest had to be totally rewritten, and/or created or re-created out of a handful of notes.

I love the word unruly. It has sort of ten thousand synonyms, all of them energetic, all of them tinged with defiance.

In the months-long writing process, I was surprised, even astonished to discover how often I made the very same sorts of writerly errors that I had warned against in Memory Into Memoir. Repeatedly, I stumbled on my own writerly questions: Oh, is that a long passage of narrative where you actually could have written dialogue and scenic depiction, Laura? Is this a lovely long passage where you have gone totally off topic and narrative-astray? Is this a place where you have in essence promised the reader something dramatic and then failed to deliver? Have you used tired phrases to evade the puddles of what you do not know? Yes, alas. All right then, revise again. Make it better. And in doing so, I came upon new recollections, new clarity, new and unexpected insight about my own life.

In Memory Into Memoir I had assured writers that their work needn’t appear in a straight chronological path, the linear distance between a Then and a Now. My own memoir essays resisted any such chain of events—and yet, they had to go into some sort of order. They’re in a book, after all! Only gradually did these essays assemble themselves, beginning with a necessary preface, and it must be said, some rickety transitions. They were, in a word, unruly.

I love the word unruly. It has sort of ten thousand synonyms, all of them energetic, all of them tinged with defiance. No one says, “My, what a ruly, well-behaved child you have.” No one says, “This is such a quiet, ruly crowd.” No, there is only unruly. And the unruly is always tinged with defiance. All pasts are unruly. Not just mine. All pasts resist the tidy codifying insistence of the page. All pasts, even the most timid and quiet of lives, will not be easily trussed up into words and pretty sentences, chunky, obedient paragraphs. The past—any past, anyone’s past—is forever balky, contrary, contumacious, noncompliant, fractious, ungovernable, insubordinate, intractable, raucous, rebellious, resistant, recalcitrant, rowdy, wayward and willful. Thus, the title of my new book of memoirs, The Unruly Past, serves as a sort of canopy over the past in general.

In writing memoir I came upon connections in my life that had never before occurred to me.

My original Fools-Rush-In response to Andrea’s suggestion (“What a good idea! That won’t take long!”) was, in a sense, true. I did this work in a matter of months. I started in early March, 2021, long hours writing, revising, showing the work to trusted, shrewd readers (“Get by with little help from my friends…”) returning to it with new eyes, and fresh resolve. I turned the final script into Andrea in late July.

And today, August 24th 2021, behold! Publication day! Paint Creek Press presents The Unruly Past: Memoirs. Bring on the bands! The pipers piping! The ladies dancing! The lords a-leaping! The drummers drumming! And let them all be wildly unruly, intractable, raucous, rebellious, resistant, recalcitrant, rowdy, ungovernable, wayward and willful. As Maurice Sendak memorably said, “Let the wild rumpus begin!”

Get Laura's posts delivered to your InboxNever miss an update!

Success!Name

The post The Unruly Past appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

June 21, 2021

Unboxing Day

The contents of this box feel like something akin to the biblical In the Beginning was the Word.

In the life of every author certain days shine, never-to-be-forgotten moments, leaving the author speechless, or misty, or perhaps even sobbing with joy: the day the book is first accepted for publication, arrival of the advance money, arrival of the first reading copy (the ARC) to hold in one’s hand… and then, surpassing all else: the book itself. Author’s copies. This day is its own celebration, UnBoxing Day as it has come to be known.

The books come in a box like any ordinary package, but for the author, the contents of this box feel like something akin to the biblical In the Beginning was the Word. Here, in hand, words-between-covers are the ideas and emotions that roiled in the author’s head. Now made tangible. Those feelings and emotions and thoughts have been transformed into an object. They now have a physical life beyond the author. To hold that book in one’s hands means that those ideas, emotions—for a fiction writer, characters—will move out of their creator’s heart and mind, and more importantly, into the hands, and one hopes, into hearts and minds of readers, distant people unknown to the author.

My books all look like foster children, a bunch of unrelated entities who happen to be on the same shelf.

This week Paint Creek Press endowed me with that indescribably wonderful feeling with the arrival of the first two of reissues of my work: the second collection of stories, Dark Continent (1989) and These Latter Days (1985) the seminal novel that first took me to St. Elmo California and introduced me to characters (and their descendants) who would populate my work for decades. They are now uniform trade paperbacks. This means that anyone can look at them on a shelf and know instantly that these books are related: they come from the same mind, the same hand; the design tells you, visibly, they are the creation of one author.

Before now my books, placed together still look random, like foster children, a bunch of unrelated entities who are happen to be placed together. Few of them have had the same publisher, their dust jackets and jacket are all motley, not at all cohesive.

Even if These Latter Days is not my all-time favorite among my books, it’s certainly the most important.

These Latter Days, my second novel began its life in the mid 1970’s as a long story, the result of one of those ideas, a what-if that often occurs to fiction writers. Miss Kitty Tindall, a 1911 Liverpool working class lass, lives with a drunken mother and a heavy-handed stepfather. Literacy allows the shallow, irreverent Kitty to feed her imagination with dashing heroes, lovelorn heroines, and grandiose dreams of singing in the music halls. One day on her way to work, she happens on a Mormon tract left by missionaries. Smitten with the drama implicit there, Kitty converts to the church. Mulling on this character I asked myself: for such a girl (burgeoning sexuality, no particular allegiance to the truth) what might ensue? I have never published this long story because Kitty immigrated to Salt Lake, and married Gideon Douglass, and once Gideon’s mother, the steely Ruth Douglass strode into the narrative, she insisted this was her story. Even before I knew it was a novel, she insisted it was hers.

Ruth fought me for years until I began to feel myself to be her servant rather than her creator. Ruth won this struggle because unlike Kitty she is strong enough to maintain a long, complicated novel. She can support a story that tests her courage at every turn, including domestic violence, religious delusion and raising six children on her own while she is tethered to the truth by lies. Kitty is a mere secondary character, her Liverpool backstory distilled into one paragraph.

Another writer might have tucked this difficult book away and moved on, but I was stubbornly set on finding print. Committed to it

My editor at Little, Brown who enthusiastically published my first novel, rejected the version of TLD that I sent him in 1978. He said he’d like to see it again if I cut it by half. I cut it by half, but in 1979 he died suddenly. The editor to whom I was assigned had no interest in it at all. One agent retired without a replacement; another agent gave up on offering the book. The novel and I were on our own. Another writer might have tucked this difficult book away and moved on, but I was stubbornly set on finding print. Committed to it. Over the next few years, and in addition to much else, I returned to revise, over and over, finishing finally in early 1982 at the Montalvo Center for the Arts in Saratoga, California.

At last—and through a series of coincidences that defy fiction—I found a publisher in Times Books (as in New York Times) who brought out the hardcover in 1985. TLD was the only novel they ever published. The following year it appeared as a mass market paperback and in hardcover and paperback in England. Then in 1998 when John F. Blair Publishing published the hardcover Caveat, they reprinted TLD as a companion trade paperback. A few years later, alas, I found TLD in a used bookstore on the floor. I dusted it off and put it back on the shelf beside the rest of the motley Kalpakian crew.

Even if These Latter Days is not my all-time favorite among my books, it’s certainly the most important; the place and the characters root many novels, and countless stories that emerged from my imagination over decades, including most of the stories in Dark Continent. And now the two sit side by side on a brand new shelf just cleared to make room for them, and the other, handsome Paint Creek Press reprints that will follow within a year.

The post Unboxing Day appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

May 3, 2021

Fools Rush In

There we were at our corporate board meeting, beers in hand, at two kitchen tables two thousand miles apart, cheering the arrival of the first offering of Paint Creek Press, Dark Continent. We had promised the world (or as much of the world as might care) that the reprint Dark Continent would be published May 1st. And here we were, the three CEO’s of Paint Creek Press, myself in Washington, Andrea Gabriel and Janna Jacobson at their home in Wisconsin, cheering on behalf of Paint Creek’s first beautiful book. In hand!

We started out with no capisce whatever of the work that would be demanded.

Paint Creek Press began as a casual convo some months ago, around Christmas time, Andrea and I on the phone chatting about how I had used snippets from my various books as examples in Memory Into Memoir (forthcoming October 2021 from University of New Mexico Press). I said I always wished I could see uniform trade paperbacks of my work, books that could sit on a shelf and actually look to be related, visibly related, instead straggling like unruly foster children from different homes. Andrea had the idea for the press, including the name, and logo. Janna vetoed the first logo idea, hence the lovely new logo that looks both like a swath of paint from a brush and meandering creek. We started out with the sort of attitude you see in those old Judy Garland/Mickey Rooney musicals from the 1930’s. Sure, kids! We can do this! Hey! Why Not! And no capisce whatever of the work that would be demanded.

In the midst of much else this past gruesome winter I began re-reading my long out-of-print books as part of the Paint Creek process, returning to them first as Word Documents, and then as PDFs. This was a very strange experience since I never re-read my books once they’re printed. I cannot revisit them without thinking, oh, I should have changed this, or made that better, or why didn’t I …

I found myself offering tsk tsk editorial advice to the writer, moi.

Nearly all my novels are baggy books in one way or another, not at all neat or streamlined, the content often struggling with structure. This winter as I re-read These Latter Days, Graced Land and Memoir Club, I found myself offering tsk tsk editorial advice to the writer, moi. There were places I could see that sheer narrative exuberance had propelled the story into flights it probably didn’t need to take. For TLD I wished I had had more faith in the story and not sliced so much out of it. (Chapters I later published as stories, but still, they could have deepened the characters in house, you might say.) I could see places where I had quarreled with the original editor, quarrels I had “won,” and now I could see that her judgment was actually right. So, all that was sobering.

But the books of stories and novellas? Dark Continent and Delinquent Virgin? No. I could not have slid a butter-knife into that prose to improve them. They still left me so emotionally slain, I could only read one story a day, and then I’d have to move on to some other undertaking.

To see this first one so handsomely bound makes my heart soar.

Dark Continent was first published by Viking in 1989. I can’t remember when it went out of print, but as with all my books, once out of print, I have got the rights returned to me. This can be an arduous, sometimes years-long process with publishers who are literally finished with the book, but require all sorts of formal bullshit from the author. My books, all except for 2019’s The Great Pretenders, are mine to reprint with Paint Creek Press, and to see this first one so handsomely bound makes my heart soar.

Dark Continent was first published by Viking in 1989. I can’t remember when it went out of print, but as with all my books, once out of print, I have got the rights returned to me. This can be an arduous, sometimes years-long process with publishers who are literally finished with the book, but require all sorts of formal bullshit from the author. My books, all except for 2019’s The Great Pretenders, are mine to reprint with Paint Creek Press, and to see this first one so handsomely bound makes my heart soar.

For these editions, I supply the content, the proofing and editing if necessary, and Andrea the artist and Janna with their enviable tech skills provide the means for that content to become an actual book. Dark Continent owes its visual and material beauty to Andrea’s artistic eye for design. In fact, when she saw the original ARC , she so hated it, she didn’t even send it on to me. Now the book in hand has nice large print, generous margins, cream-colored paper, interesting interior motifs and drop caps which I especially like because they remind of of all those 19th century books I always loved. Now that the design and other apparatus are in place (a process I absolutely do not understand) once the content is ready, each volume can go forward across all selling platforms as e-books and uniform trade paperbacks.

However different these novels, stories and novellas may be in terms of their focus, their voices, their sometimes noisy, warring, and far-afield struggling storylines, they will all eventually line up on a shelf, Paint Creek Editions, visibly, tangibly related to one another and to the mind, the writer who first brought them forth so long ago.

The post Fools Rush In appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

November 30, 2020

To The Lighthouse

Virginia Stephen, born in 1882, was part of a complex, blended family full of Eminent Victorians on both sides. Her father, Leslie Stephen (1832–1904) was one of those 19th century intellectuals whose literary output and energy (The Dictionary of National Biography, for one!) boggles the mind. Her mother Julia Duckworth was his second wife; they each brought children to the marriage, and had four more together, Vanessa, Virginia, Thoby and Adrian. The family summered in Cornwall at Tallant House near St. Ives.

Julia died in 1895 when Virginia was just thirteen, a crucial loss that sparked an early breakdown for her, and plunged her overbearing father into bleak, demanding gloom. When Leslie Stephen died in 1904 the younger Stephens abandoned their staid home, 22 Hyde Park Gate and moved to then unfashionable, bohemian Bloomsbury. They set up house together, and entertained reams of lively friends and lovers who became the core of the famous Bloomsbury Group. Thoby died of typhoid in 1906. Vanessa married Clive Bell in 1907. And then there was Miss Stephen, solo. Certainly not friendless, but bereft nonetheless. She married Leonard Woolf in 1912.

Julia & Virginia Stephen

Young Virginia

As a reading experience nothing else has ever quite equaled the first time I read To The Lighthouse.

I have tried to read nearly all of Virginia Woolf’s work including the published letters and diaries. Many of her novels are too cerebral for my taste; they lack a sort of exuberance or energy without which, for all their artistic refinement (for me) they are pale, unmemorable. Three of her works, however, are seared into my memory, indeed, into my life.

“The Death of the Moth” was the essay she wrote shortly before she waded into the River Ouse to drown herself in March,1941. It reduces me to pulp every time I read it. A Room of One’s Own….once beyond those early pages (the prunes and custard put me off) I felt like the Great Virginia had taken me by the shoulders and throttled me until my teeth chattered while she screamed at me: Do it! Write! (I’ve described that experience elsewhere.) But To the Lighthouse! What a gem! I still return to it again and again, year after year, always finding some new nugget of craft or understanding in its pages. As a reading experience nothing else has ever quite equaled the first time I picked up this novel.

In every paragraph one feels unceremoniously dropped into a cauldron of competing consciousnesses.

I was in grad school though I cannot now remember if To the Lighthouse (1927) was assigned for a class. Doesn’t matter. I am a fast reader and I moved through Part I at my usual clip, strumming through the story of a huge Edwardian family (eight children!) and their guests at their vacation home (set in the Hebrides). I found the novel difficult; the point of view roams all round, and in every paragraph one feels unceremoniously dropped into a cauldron of competing consciousnesses. And really, all these people and their dinner party? Minta’s brooch? Stuffy Mr. Tansley? Greedy Mr. Carmichael? Grim Mr. Ramsay. Prim Lily Briscoe. High-spirited Cam. Poor little James. Many of the characters are like a bunch of cats in a bag, and some of them rather unpleasant as well. Mrs. Ramsay in her emollient way holds the whole day/evening/family/meal together.

The Stephen House

I asked myself: what kind of author unceremoniously offs their central character?

[image error]Then I came to Part II, “Time Passes” which is equally unconventional narrative, but in a different way, swift, scenic pastiches over events, including the Great War. Part II ruffles through the lives of this family and the guests we met that memorable evening. Poor Prue Ramsay, dead in childbirth. A son, dead at the Western Front. Amid these random revelations we return regularly to the empty, decaying house as if it too is a character.

Reading along I suddenly stumbled on a bit of info that Mrs Ramsay had died. What? What? I was stricken! What did she die of? I must have read so fast that I missed something! I must have missed where she was sick. So I returned to the beginning, and read carefully. No mention of her being ill or any such thing. I asked myself: what kind of author unceremoniously offs their central character? And that’s when I realized that I had responded to Mrs. Ramsay’s death just as if she’d been a real person—an experience altogether new to me as a reader. I felt the cold shock of her death as though I had personally known, liked and admired Mrs. Ramsay. And, as an unexpected death often does, the loss of Mrs. Ramsay changed the way I looked at everyone. Beginning with Mrs. Ramsay herself.

People said she really was an unremarkable woman. What had she done in the world, after all? Here she is, middle-aged, mother of eight, who managed a household and created a social milieu helpful to her difficult husband’s academic career. But revisiting Part I, the reader sees, with a bright shock of recognition, that she was remarkable! A solar center radiating into her own little universe, the bright rays of her being, warming everyone who came within her orbit. She had such tenderness for everyone—whoever they were. That opening exchange of dialogue conveys that tenderness. She tells the little boy, James, yes, we’ll go to the lighthouse tomorrow if the weather is fine. Mr. Ramsay immediately tells the kid, in his pompous Edwardian fashion, the weather tomorrow will suck. But Mrs. Ramsay could also be fatuous and a little shallow, pleased to see everyone around her table that candlelit evening, though she is prickly with Mr. Carmichael when he asks for a second helping of soup. She is certain that marriage is good for everyone, and even fancies that she might link Lily with one of the other guests. She has such hopes for young Minta and Paul, that they will get engaged while they’re here.

And then in Part II we read that yes, Paul and Minta married, but within a decade they are thoroughly nasty to one another and unfaithful, and that day on the beach, hunting for Minta’s brooch, that was as good as it was ever going to be for them. Part II ends with the house, and revelation dawns slowly upon the reader that really, our days—the best, the worst, the most ordinary—slide into and under and wash away all the little petty concerns that make us happy or cranky, or pompous or whatever we are. All of our little universes are important—and ephemeral. The novel is an unequaled, exquisite cocktail of temporality and mortality.

Time has tempered everyone. They go to the lighthouse.

Part II, Time Passes” with its relentless mortality and decay does not dim the great achievement of Part I. Here we see Mrs. Ramsay’s gifts concentrated into a single day, and within a finite group of people. This is a great writerly feat. Wrangling a character with such ineffable gifts to the page is not easy. You can see this struggle in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night, in that opening beach scene, his narrative efforts to convince readers that Dick Diver has these same gifts, generosity of spirit, ease and affection that communicates itself to others. Fitzgerald uses a distant third-person narrator, someone looking on, just as the reader is looking on. The Great Virginia’s third-person narrator weaves in and out of all the characters’ minds and hearts, and so the portraits are intimate, each person’s estimation, judgment, colored by their pasts and aspirations.

In Part III about ten years have passed. It’s after the War. Some of the people from Part I return to the house for the first time. Cam and her brother, James, grown now. Their father, Mr. Ramsay, Mr. Carmichael, and the artist Lily Briscoe, still pondering perspective in the painting she had begun ten years before. They go to the lighthouse. Time has tempered everyone.

To the Lighthouse, though not a memoir, shimmers, takes one day as a sort of prism. The difficult, disappointed Mr. Ramsay in the novel probably reflects more gently on Leslie Stephen than a memoir would have. Julia Duckworth Stephen as Mrs. Ramsay offers unstinting warmth along with a dollop of indulgence to just about everyone. The author is the modernist icon, the Great Virginia, but I cannot help but think of the former Miss Stephen, as her pen raced across the page, how she must have must have reveled, recreating whole summers of childhood, distilling them into that one day.

Art too has its limitations.

Literary critics, and more learned minds than mine, have spilled buckets of ink over To the Lighthouse, particularly over Lily Briscoe. Many cite her as the character with vision, that her care in composing her picture is the true artistic core of the novel. They say Lily stands in for the Great Virginia, the outsider, the artist. To this, I say (in the immortal words of my college roommate) win-a-win-few-a-few. Lily is too prim, too precise to stand in for the Great Virginia who clearly had an exploratory mind. The reader likes Lily, and her ruminations on art are genuine, and interesting, but is she the beacon in this book? If so, well, then (it seems to me) art too has its limitations, doesn’t it? Is art, her painting, truly any more satisfying, more meaningful than the gathering among the candles and the summer twilight? One endures as artifact. One endures as memory.

Shed your story-telling expectations, and the novel will take you in its current and take you to the lighthouse.

The narrative style of To the Lighthouse is challenging. The interior thoughts, the dialogue, the consciousness of different people are awash in the same paragraphs with no respect given to the pickets of conventional narrative prose (in which stuff like this ordinarily does not happen). But if you shed your story-telling expectations, go with the flow—and, admittedly, read the book more than once—this novel will pick you in its current and take you to the lighthouse.

The post To The Lighthouse appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

November 11, 2020

The Heart to Artemis: A Writer’s MemoirBryher

The Heart to Artemis is one of those rare memoirs that, at the end, leave the reader more curious about the writer than when she began the book.

Bryher was born Winifred Ellerman in 1894. Note I do not say that Winifred Ellerman was her real name. It was not. Bryher was the name she wrote with and loved with and had her being, the name she gave herself. She took it from one of the rugged Scilly Islands off the Cornish coast, a place she found enchanting. Not counting the book of poetry her father paid to print when she was twenty, Bryher published at least seventeen volumes in her lifetime (1894–1983) fiction and nonfiction on an array to subjects and eras, nearly all of them unread now. (The Heart to Artemis and two other volumes were reissued by Paris Press in 2006.)

I first stumbled across The Heart to Artemis when I was in grad school researching the complicated literary, artistic, romantic and sexual alliances of the World War I generation of writers and artists, lives forever upended by the Great War. Her unusual name kept coming up. Now that I’m revisiting her memoir, apart from those lives, she seems to me even more interesting.

In the years before the Great War, the height of women’s fashions was the hobble skirt, narrowed at the ankles, a fitting metaphor if ever there was one.

Bryher steadfastly describes herself and her family as decidedly middle class. In truth, she was the daughter of one of the wealthiest men in England (ever) a fact she does not mention. Though she taught herself to read at the age of three, travel—long momentous journeys traveling and living in France, Italy, and Egypt—dominated her childhood, and fills the first third of the book.

But when she was fifteen, the family’s traveling adventures came to a close. They returned to England, to the Sussex coast to stay planted there. Bryher attended a nearby girls’ boarding school, Queenswood, where, oddly, given her solitary, peripatetic childhood, she prospered. Never having had a friend before, at Queenswood she made friends for a lifetime. At age eighteen or nineteen she was intellectually ravenous, and undecided in an era where educational and artistic opportunities for women were cramped. As she makes clear, Bryher, almost literally, could not move without affronting propriety. High fashion in 1911 included a hobble skirt, narrowed at the ankles, a fitting metaphor if ever there was one.

Reading her memoir, I could not help but think that perhaps these Edwardian restrictions actually worked in Bryher’s favor. Clearly, she could have been a fantastic archeologist, a linguist, even a philosopher; indeed she dove headlong into all of these pursuits, but made a profession of none. Given the swath of her reading, her acquaintance, her sheer engagement with the world, her eagerness to open herself to experience (from psychoanalysis to flying lessons to creating cinema) any singular profession would have hobbled her as much as that Edwardian skirt. Still, once out of school, living with her parents, she was, so to speak, clapped in the iron grasp of maidenhood.

How to get out of this? Well, marriage would do. She made the first of two marriages of convenience in 1921 to Robert McAlmon (1895–1956) an ambitious, impoverished American writer living in Paris. McAlmon used Bryher’s abundant money to start Contact Editions that published some of the most stellar names of modernism, both European and American. They divorced in 1927, and she made a second marriage of convenience, to film maker and critic Kenneth MacPherson (1902–1971). This collaboration (as opposed to a union) created the legendary journal, Close Up that brought distinguished film criticism to an international audience. With MacPherson she produced the seminal avant-garde film Borderline, starring the incredible Paul Robeson and the American poet, H. D.

The book is full of blithe refusals.

The Heart to Artemis is matter-of-fact about contractual nature of these two marriages. She is less forthcoming about other aspects of her life. In fact, I admired her picking over exactly what she was prepared to say…and what she wasn’t. The book is full of blithe refusals to tell-all–hence my curiosity when I finished it! She was an unapologetic lesbian, and there’s nothing coy in these pages but neither is there anything raffish. The love of her life, the American poet, H. D. (Hilda Doolittle) appears in a few memorable, even moving scenes, but the depth and complexity of their relationship (and its rifts and rocky moments) those are not here.

All sorts of things are not here. No mention whatever that she and MacPherson legally adopted H. D.’s daughter Perdita. Perdita scarcely shows up. Of Bryher’s own family, the lapses are legion. She adored her parents whose first names are never given, nor is the name Ellerman. Not till page 134 are we told that she was fifteen when her parents were able to marry. Why they could not marry? Not a word. (Later, in life, offered the opportunity to have her birth certificate amended to “legitimate,” Bryher refused.) Shortly after her parents legally married they had a second child. She says nothing of this brother. In 1933, with the death of their father, the siblings quarreled in ways that must have torn the family apart. Bryher acknowledges the quarrel in spare terms. The brother, always nameless, is never mentioned again.

The model Kiki literally entered the room as Nude Descending a Staircase, “wearing a couple of soap bubbles and a towel tied where she did not need it.”

Bryher was an exemplar of that World War I generation, women and men who lived through the cataclysm, and emerged forever changed. Bryher writes that war, for all its awfulness, freed them. The book is at its liveliest, its most ebullient describing these freedoms demanded by a generation, herself among them, who ruthlessly sought out and embraced the New.

Bryher lived in Paris at the height of all that post-war artistic ferment, but she was not one of those who merely flung herself from café to cabaret in a search for sex, sensation, or inspiration. She chronicles one such evening in detail, but remains an astute, observant outsider. She did not drink, and that too made her something of an outsider. My favorite of her Montparnasse anecdotes is that of an evening at the studio of photographer Man Ray where the model Kiki literally entered the room as Nude Descending a Staircase, “wearing a couple of soap bubbles and a towel tied where she did not need it.”

Beginning in 1933 her home in Switzerland offered sanctuary to refugees fleeing the Nazis.

Born British, Bryher was a true European, comfortable with many languages and in many venues. She made her home in Switzerland, but traveled restlessly, extensively all her life; perhaps a taste, a need for travel came from those early childhood years. She went to India and America; she adored Americans. (Except for Ezra Pound who made a pass at her, she did not love him, and she did not love William Carlos Williams.) She was analyzed by Freud and one of his acolytes, Dr. Sachs. She seems to have known or at least met every important artistic personage in those Between-the-Wars years.

For all her immersion in European artistic currents, Bryher was attuned to the menace, aware of the rise of Fascism that rumbled under that rich culture. Beginning in 1933 her home in Switzerland offered sanctuary to refugees fleeing the Nazis. Travel became increasingly difficult, and throughout the 30’s fraught with bureaucracy. All this upheaval occupies the last third of the book until war was declared in September 1939, and France fell to the Nazis in June 1940. By that time her efforts helping Jews escape had not gone unnoticed. Informed unofficially that she was on the Nazi blacklist, Bryher’s last chapters recount a harrowing journey from Switzerland trying to get to London in the months after Dunkirk. She stayed briefly in Paris with Sylvia Beach and saw Walter Benjamin there for what would be the last time. He would commit suicide in the Pyrenees trying to escape the Nazis.

Bryher’s prose throughout the memoir is what I would call cool, never overwrought or emotional. Even in the very last scene. After all the perils she endured to get back to England (rendered in detail) Bryher arrives at H.D.’s London house, glad to see it still standing, not bombed like so many others. Sitting on her suitcase on the step, Bryher awaits H. D.’s return. Looking at all the neighboring houses’ blacked out windows, she reflects bitterly that she had tried to warn her British compatriots what was surely coming. At last H.D. returns home, and of her reunion with her lover of almost thirty years, Bryher remarks only that she “felt a little better” to see HD’s look of astonishment. That paragraph, the book itself ends with the lines, “The sirens started, the guns began and we went with our blankets to the shelter downstairs.”

She must have been one of the most cosmopolitan women of her era. Maybe any era.

The post The Heart to Artemis: A Writer’s MemoirBryher appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.