Laura Kalpakian's Blog, page 10

October 4, 2016

September/Remember

Perhaps because September rhymes with Remember, because one can feel the light change, and days diminish, and see the petunias, so gaudy all summer, pucker up and die without farewell, it has always seemed to me the most nostalgic month. September presupposes loss and loss always sharpens memory.

Thus, Red Wheelbarrow Writers Book Club—our intrepid band of dedicated readers and writers—always chooses Memoir for September. I write this knowing it is October and I am utterly derelict.

Victoria, a garden writer, brought garden memoirs, beginning with Michael Pollan’s SECOND NATURE, a gardener’s education, linked essays she describes as intellectual history and environmentally opinionated. MRS. WHALEY AND HER CHARLESTON GARDEN by Emily Whaley, an elderly writer graciously opinionated with an engaging voice. EPITAPH FOR A PEACH by David Matsumoto which Victoria loved for its poetic insights and insightful prose.  Then there is GREEN THOUGHTS by Eleanor Perenyi, a vintage book, if I’m not mistaken, not Vintage like the publisher, but vintage as in from the past. Victoria termed these essays arranged alphabetically, as acerbically opinionated. Nice to know that garden writers can wield the pen as well as the spade.

Then there is GREEN THOUGHTS by Eleanor Perenyi, a vintage book, if I’m not mistaken, not Vintage like the publisher, but vintage as in from the past. Victoria termed these essays arranged alphabetically, as acerbically opinionated. Nice to know that garden writers can wield the pen as well as the spade.

Marie brought some of her favorite memoirs of childhood. BONE BLACK by bel hooks, very short chapters, some in first person, some in third, describes the feminist writer’s Alabama childhood. Harry Middleton’s FLY FISHING, TROUT AND A LIFE WITH OLD MEN begins in 1965 in Guam and tells the story of a boy sent to live with two old uncles. Beautifully written and expresses the young boy’s mind and voice. Marie also shared a unique looking graphic novel, Lynda Barry’s ONE HUNDRED DEMONS about a first generation Tagalog family

Frances admired THIS BOY’S LIFE by Tobias Wolff and A BOY’S OWN LIFE by Edmund White, published in the early 80’s before AIDS cut its swath through the gay community. She also touted Gerald Durrell’s MY FAMILY AND OTHER ANIMALS.

Pam brought all three Mary Karr memoirs, THE LIAR’S CLUB about her childhood, CHERRY about her misspent youth, LIT, about her alcoholism that opens with her in a ditch wearing high heels. Overall assessment: the mark of a great writer is to consistently weave tales that keep you anchored to the book. Pam also touted Alicia Abbott’s memoir of her father. Alicia was raised in San Francisco by her father at the height of the AIDS epidemic, and while she was still very young, her father’s friends all began dying.

Jes, a seasoned and dedicated sailor, chose books about boaters: “Bad times of being on the water” from different perspectives. Her first A CURVE IN TIME is the story of a widow in the early 1950’s who took her five kids up through the Inside Strait. These were originally a series of newspaper articles later cast into a book. A wonderful book and required reading for PNW residents. (A boating amigo gave me this book when I was researching EDUCATING WAVERLEY which is set in the San Juan Islands in the 30’s. It became one of my favorite memoirs as well.)

Jes also cited two books in contrast to one another, the first ADRIFT by Stephen Callahan tells a boating story in which the Narrator is “about to die at every moment,” and a great crybaby. Jes wanted to slap him. I wanted to slap him as she talked about the book. Conversely, MAIDEN VOYAGE by Tanya Aebi tells the story of a woman who sailed around the world by herself. She lost her title to this incredible achievement because she stopped to pick up a stranded friend. The Narrative Voice in the book changes from an unsophisticated writer to later, when an editor got hold of the material and enhanced it.

For myself, choosing among the gizillions of memoirs I have loved is always difficult. I brought with me one of my all time favorites, OLEANDER, JACARANDA by the British writer, Penelope Lively which circles round her childhood in Egypt during World War II. Her father was posted in Cairo as part of the diplomatic corps and when, at the war’s outset, British women and children were sent home, she and her mother stayed. There is a great story here of maternal neglect but the charm, the deep fascination of the book is its self-conscious questioning of the past. The narrator asks: do I really remember that? Have I somehow transposed these elements? Lively used the idea of the palimpsest, and Egypt itself, the notion of excavation and restoration in ways that are not merely moving, but provocative. This book, sadly, is out of print now.  She had a new memoir out last year, DANCING FISH AND AMMONITES which I promptly bought and eagerly read and found disappointing, a diary more on the order of “My Elderly Days,” and how well I’m doing.

She had a new memoir out last year, DANCING FISH AND AMMONITES which I promptly bought and eagerly read and found disappointing, a diary more on the order of “My Elderly Days,” and how well I’m doing.

September 18, 2016

Smudge Pots

September 17, 2016

Bravo and Encore!

Last night’s launch for the Red Wheelbarrow Writers anthology MEMORY INTO MEMOIR was the most festive occasion in my recent memory. The people, the presentation, the warmth and sheer energy pulsating around Village Books’ readers’ gallery created one of those rare, spontaneous moments one is privileged to experience, genuine collective energy. In our case, a collective memory.

Chief among the pleasures of the evening for me was that my mother, Peggy Kalpakian Johnson was one of the readers. Her contribution to the anthology is a piece excerpted from her family memoir called SUNSHINE AND SILENCE, about being a student at University of Southern California during World War II. Moreover yesterday, September 16th was my parents’ 72nd wedding anniversary. Theirs was a wartime romance: a young man in the navy meets a chic USC student at USO dance. The rest is history.

Truly history. History is what we were all giving voice to last night. The readers were giving voice to their own personal history. Together we were giving voice to our collective history as the Red Wheelbarrow Writers, a choir of narrative voices who, but for Red Wheelbarrow would not have come together, would not have published this fine book.

Tonight, Saturday September 17th there will be a reprise! And by popular demand, my mom, Peggy Kalpakian Johnson is doing an encore of SUNSHINE AND SILENCE. Come to Village Books at 7 and join the choir!

September 15, 2016

Memory into Memoir: The Anthology

Friday marks the publication of the Red Wheelbarrow Writers’ first book MEMORY INTO MEMOIR. Published by Penchant Press, the book will available for purchase at Village Books starting tomorrow, September 16th at 6 pm. Join us then for the launch and the reading. The celebration continues on Saturday at 7 pm.

Friday marks the publication of the Red Wheelbarrow Writers’ first book MEMORY INTO MEMOIR. Published by Penchant Press, the book will available for purchase at Village Books starting tomorrow, September 16th at 6 pm. Join us then for the launch and the reading. The celebration continues on Saturday at 7 pm.

This anthology represents the work of a vital, lively literary community in Whatcom County. Red Wheelbarrow Writers came together to write, edit, produce, fund, market and see all aspects of the book to fruition.

Red Wheelbarrow Writers is a loose affiliation of lively writers. We pay no dues. We have a happy hour once a month where people can read five minutes of their current work if they wish—and drink wine. We have a Book Club once a month where members meet to discuss books they have loved–or hated–and drink wine. We are a supportive group who have enriched one another’s lives immeasurably.

This book testifies to that spirit.

September 7, 2016

Honolulu, 1981: Memoir

When my Armenian grandparents emigrated in 1923 with their two little daughters, among their effects listed in the Kalpakians’ Declaration of Household Goods were a set of enameled tin dishes, blue on the bottom, white on the top. Somehow these came to me and I took them with us in all our travels. Especially in the early years of my eldest son, Bear’s life, we lived in many places. I always thought of my grandparents when I would pack them for our various journeys.

My husband, Jay McCreary, an oceanographer, often had temporary research gigs in interesting places, one of them University of Hawaii, Honolulu where we lived in 1981. That summer we were installed in faculty housing, best described as a sort of international intellectual three-storey concrete slum. Academics from all over the world brought their families, and some had clearly been camped here for years. At dinnertime the exotic smells coming from these crummy apartments was enough to make you walk along the concrete corridor just to inhale.

The apartment doors (and kitchen windows) all opened along this corridor. [See photo above, Bear flanked by two friends in the concrete hall] But once inside the apartment the sliding glass doors opened on to balconies, and a dazzling view of Diamond Head, and the distant Pacific, a million dollar view from this two bedroom furnished slum, especially since we were on the top floor. Below us was the parking lot and other faculty housing units for single people. Joel Picaut, a French oceanographer friend and colleague, lived in one of those on the first floor. That summer passed with many parties and picnics that have long since muddled into a general sense of well-being there, but one incident, one such party I shall never forget.

Late one afternoon in August Jay called home, and behind his voice I could hear all kinds of laughter and roistering. He said the Soviet Union’s research vessel had come into the Port of Honolulu and Soviet scientists had called the University of Hawaii inviting their oceanographers to come aboard. Remember in 1981 the Soviets were still fighting the Afghans; indeed, America had refused to participate in the 1980 Olympics to punish the Soviet Union for invading the Afghans. In short the Cold War was in fine fettle and so the invitation to come on board the Soviets’ ship was an unusual one. In fact it was rare in those days for a Soviet research vessel to be allowed into the port of Honolulu at all

Jay said that he and the other oceanographers had been there all afternoon, drinking vodka and talking science. Science was waning, but the party was just warming up. Why didn’t I get a baby-sitter for Bear and come down to the harbor–and bring some of my women friends.

Obligingly I made a few phone calls found a babysitter for my son and then with some girlfriends drove down to the wharf. I had asked my husband how I would know the ship and he said: Oh, you’ll know it. It’s berthed next to the Kana-Keoki, the University of Hawaii’s research ship. Indeed no one could have mistaken the gleaming Queen Mary of a Soviet research vessel parked next to the plug-ugly Kana-Keoki. My girlfriends and I wandered on board, greeted with smiles, which we understood and language we didn’t. We found my husband and the men from the lab who, by this time, had altogether forsaken science for laughter and music and drinking. Oh, the drinking!

My husband introduced us to Sergei who spoken fluent English, the only one who spoke English at all. Sergei served as translator for everyone. These Soviet scientists were generous and courteous, in fact downright courtly. They showed us picturers of their families and gave away cigarettes and candy and gew-gaws; to this day I have still have pins and mementoes of the 1980 Moscow Olympics which I doubt many Americans own.

Everyone eventually gathered in the spacious galley where many of the Soviet crew and scientists were performing on a small stage with a microphone flanked by hammer and sickle Soviet flags. The men played different instruments, sang solos and duets, danced those incredibly athletic dances. As each of the various performers came on, Sergei told us a bit of their backgrounds, what they did on the ship and so on.

Then there came up to sing a swarthy man; he had a full beard, dark eyes, thick brows and a high nose, and he was probably my age, early thirties. He stood and sang the saddest song I have ever heard. Everyone who had been cheering, clapping time for the other singers, dancers and musicians quieted, and Sergei whispered to me that the man was singing about the sadness of his people, the losses, the heartbreaking separations. Sergei said he was a surgeon, fulfilling state service on this vessel. He was an Armenian.

“Really?’ I said, “I am Armenian.” And I told him my name, not the name I was born with or married to, but he name I had chosen, Laura Kalpakian.

When this man finished singing, Sergei beckoned him to our table and introduced us as Armenians. The surgeon’s face lit. Never in my life has a stranger looked at me with such affection, with such warmth, and such happiness! And from the depth of all those church picnics with my grandmother, from the kebab-fire smoke and the old men smelling of Old Spice and the dust and the heat and geraniums, from the smell of the coffee and old women pulling me up against the buttons on their dresses, from all that I drew the one word my grandmother had taught me to use on these ceremonial occasions. I said Inchbessess.

The surgeon pulled me into his embrace and called me his sister. This man sailing under the hammer and sickle of the Soviet Union , embraced me, my husband, my friends. From that moment linguistic barriers, if they did not crumble, at least they cracked, these fissures helped along by more drinking and feelings of such warmth and camaraderie as, with Sergei’s help we talked and exchanged info and pictures of children and families. The Armenian surgeon (whose name, I have alas forgotten) insisted he should cook Armenian dinner for me, my husband and son, the other American scientists. Tomorrow night, we all agreed, tomorrow the Soviet scientists would come to faculty housing, the surgeon would do the cooking. We would all contribute something. The party was to be in our friend Joel’s apartment. Joel’s flat was on the ground floor, cooler because of the shrubs and trees around it. We borrowed chairs and tables and lined them up end to end in Joel’s apartment.

The next evening the Armenian surgeon, Sergei and a third Soviet scientist (Jay thinks his name was Eugene) arrived. How they got permission to get off the ship and come to the University of Hawaii, I do not know. How the Armenian surgeon came by the ingredients for his dish, I do not know, but he had spent the entire afternoon rolling up grape leaves in a dish my grandmother called derev and some call dolma. He brought this main dish, enough for all of us, and the other Soviets brought vodka, wine, musical instruments; the Americans contributed salads, desserts and cold beer.

The Soviets arrived in time to see the little children of faculty housing put on a play of Cinderella in the parking lot. (Headlights sufficing for footlights.) Cinderella had been organized by a particularly bossy little girl age ten. She rounded up all every kid who could walk; she directed and starred as Cinderella. My little son Bear was a page or a herald to the prince. All the many parents stood around the “stage,” watched and applauded the international cast. The Soviets were amazed, and a little misty, no doubt thinking of their own sons and daughters far away.

After the play ended, we all went to Joel’s apartment. We were perhaps fifteen adults, two or three children and it was a Honolulu August night, jalousied windows open and the palm trees rustling outside, the scent of plumeria wafting in. We communicated in the two universal languages music and laughter. (There is another universal language of course, math, but math mercifully got banished for the evening.) We struggled with the less universal language; some Soviets could speak fluent French so Joel translated. My schoolgirl French was just barely equal to the Soviets’ rusty French. We ate and drank and in the course of the meal each of the Soviet scientists pushed back his chair, rose, and offered a toast, more than one. Sergei translated. The Americans too stood and offered toasts and Serge translated for us as well. For all our mirth as we raised our glasses and voices, one by one, the occasion took on a sort of solemnity: we would likely never meet again and this rare moment should be prized, perhaps even formalized. We saluted peace between our countries. Peace in the world. We drank to the hope that the camaraderie, the affection and respect created here, this night, in the middle of the Pacific would be a harbinger for the future, for the hope that our children could one day meet in peace s friends and comrades, that political boundaries would fall and understanding ensue. We were so moved in the course of these toasts, we wept.

In 1981 none of us, children of the Cold War, could have foretold that in a decade these men would not be Soviet citizens. They would once again be Russians or Armenians, Ukrainians, whatever else their ancestors had been born to. In 1981 no one at that table could have foreseen events in 1989 would stand in history, a landmark, like 1789, not perhaps the turn of the century, but without doubt, the end of an era.

Where is that Armenian surgeon now? The man who on the strength of my single Armenian sentence embraced me and mine, where is he? Where is his wife whose picture he so proudly showed? Where are the sons he so hoped would meet my son. I wonder if in the course of the all too human events which have befallen Russia and Armenia, the world, for that matter, does he ever think back to Honolulu when a single Armenian word united us all? Does he remember the trade winds blowing through the open windows, the glasses raised in toasts to peace?

After the meal the scientists broke out their instruments and performed again, the Armenian surgeon singing a new song, not so sad. The Americans too, I think performed, but the particulars escape me. No doubt due to all the vodka and the wine, tho I remember much noise, music and hilarity wafting out the open windows.The third Soviet scientist decided when it was time for them to go, and like Cinderella hearing the stroke of midnight, the other two immediately jumped up and obeyed.

After the Russians left, the cops came. They asked to see ID from Joel, issued grave warnings about noise, and broke up the party. When the cops left, we all agreed: good thing the Soviets weren’t here to see this. Imagine what they would have thought of the black uniforms, the white helmets, the nightsticks and firearms in the cops’ belts.

Some years later at a scientific meeting in England, Jay again saw Sergei and the third scientist, Eugene. We always believed that one or both men acted as KGB agents, and no doubt that’s how permission to leave the Soviet research vessel was granted at all. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Jay never again saw them at international meetings, and word is that those gleaming, gorgeous Soviet research vessels have long since been sold off.

Though I do not remember his name, I shall never forget that Armenian surgeon. I had never before experienced the power of the diaspora: that a single Armenian word could unite an American and a Soviet citizen in a shared tradition, though we did not speak the same language, and though our lives were incomparably different. That August 1981 evening remains for me unique, makes me believe that all those people whom history has persecuted, starved, denied reviled and finally exiled, will be at an advantage in the world to come. The Jews, the Chinese, the Irish, the Indians, the Armenians, anyone whose people have lived in a diaspora are endowed, of necessity, with a complex identity, empathy and connection among strangers occasioned by a single spoken word.

No Business Like Show Business……

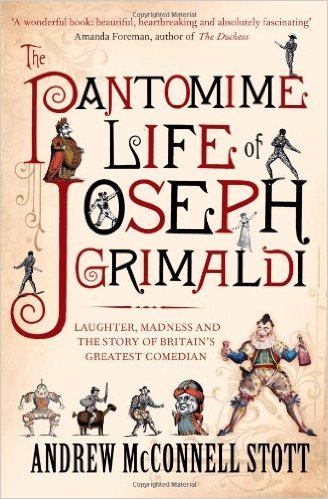

Not to put too fine a point upon it: THE PANTOMIME LIFE OF JOSEPH GRIMALDI is one of the best books ever written about the world of the theatre. It is, as they say, full of character and incident: a wonderful introduction to the ribald, sleazy, corrupt, energetic and wholly unpredictable Regency. Impeccable research, terrific editing instincts and an eye for the telling anecdote, and at the same time, a sense of pathos, this book chronicles far more than a mere life and times. Joseph Grimaldi, 1788–1837, the clown whose biography lies at the center of the book gave his name, Joey, to the practice and profession of clowns ever since.

Not to put too fine a point upon it: THE PANTOMIME LIFE OF JOSEPH GRIMALDI is one of the best books ever written about the world of the theatre. It is, as they say, full of character and incident: a wonderful introduction to the ribald, sleazy, corrupt, energetic and wholly unpredictable Regency. Impeccable research, terrific editing instincts and an eye for the telling anecdote, and at the same time, a sense of pathos, this book chronicles far more than a mere life and times. Joseph Grimaldi, 1788–1837, the clown whose biography lies at the center of the book gave his name, Joey, to the practice and profession of clowns ever since.

Grimaldi’s life has long fascinated this reader. Before this there was only a slim volume biography which, though enough to fascinate, felt thin. Andrew Stott’s brightly bulging volume does not disappoint. The author’s skillful, readable weaving of the influence of current events (it was not then history; they lived it) on the lives of the many characters here, on the theatre itself, on the life and more to the point, the livelihoods of troupes of actors, musicians, clowns, managers and magicians who broke their hearts and occasionally their very backs to bring entertainment to a hungry and passionate public. The author’s own background as a comic and not a mere academic infuses the narrative with a deep vein of understanding. Even if you care nothing for the theatre or for the Regency, read it as an antidote to Jane Austen’s prim Regency. The This book will take you far away and fill you with both delight and sadness. A gem.

August 16, 2016

Beach Reads and Other Sins

Guilt Free Reads

Graduate school is the incubator of snobbery, particularly in the arts. In graduate school I had professors who spoke of “lit-retch-ure” in a way that kicked sand in the face of anyone not certifiably gaga for Derrida. To indulge in a Beach Read—any work by a popular author (even a once-popular author, like the 19th century Mary Braddon)—cast you, the reader, immediately out of the rarified elite, and down into the company of the dormouse. When the Red Wheelbarrow Writers Book Club chose Beach Reads for August, I—clearly still suffering grad school hangover—added the tag, “guilty pleasures:” the books you didn’t like to admit you enjoyed. Little literary sins.

The Red Wheelbarrow Writers mercifully do not suffer from these sorts of literary sins. Quite to the contrary these writers brought to the August Book Club Beach Reads a vast array of possibility and expression. Indeed, as working writers they all agreed that they didn’t feel guilty about any time they spent reading. No matter what. Jes Stone said for guilty pleasure she watched old British comedies on Hulu, snuggled with her cat.

Janet Oakley, a historical novelist, loves the great, thick tomes of M. M. Kaye (Shadows of the Moon) and Diana Gabaldon (the Outlander series). She also loved Robert Ludlum’s Bourne Identity and Benchley’s Jaws, perhaps the best summer book ever written.

Beach Reads equate with escapist pleasure and for Victoria Doerper, Donna Leon’s mysteries set in Venice offered her just that. Victoria read all of the twenty-five books in the series in one summer as an antidote to an ongoing health crisis in the family. Waiting for the next Donna Leon, Victoria picked up Jennifer Chiavernini’s historical novel The Quilters’ Apprentice, stories about characters and relationships and an art she knew nothing about. Now she does.

Sean Dwyer also relished a beach read series for what he could learn from them. Cemetery Dance is one of ten books by dual authors, Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child. Set in New Orleans these mystery-thrillers are addictive, meticulously researched and the reader comes away both informed and entertained. Frances Howard-Snyder indulged regularly in the Elizabeth George novels, and more recently the charming best seller The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Club set in the Channel Islands during the Occupation.

Pam Helberg has also freed herself from guilt which is a good thing for a person in a masters program for clinical mental health counseling. Her list was the most eclectic of all, from the most recent Pam Houston, Contents May Have Shifted to Mary Doria Russell’s sci fi, The Sparrow about Jesuits in space. Yes, you read correctly. Pam’s Beach Reads included a find like The Essential Rumi, a poet from ancient Persia and work by Kay Jamison, a writer who has explored madness and creativity and then, more personally, in The Unquiet Mind described her own bout with mental illness. Mental illness also figured in Ellen Forney’s graphic novel Marbles

Susan Chase-Foster in her well-traveled way, brought in books that she had read on beaches far and near. She read The Prince of Tides (and loved it) on Cape Breton in Nova Scotia, and a Robert James Waller volume, Puerto Vallarta Squeeze read, naturally, on the beach at Puerto Vallarta. Again, in Mexico she read Frieda Kahlo’s diaries, an absolutely beautiful book that reproduces in full color Kahlo’s diaries and doodles, illustrated meanderings. Susan read Anthony Doerr’s Shell Collector (collection of stories) on a recent beach, and my own Steps and Exes on a beach here in the Puget Sound. Steps is set on the fictional Isadora Island. For her upcoming trip to Alaska, Susan is taking Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube, Adventures in Norway and Alaska, and promised to tell us about it on her return.

Hearing these evocative descriptions of so many books, I felt relieved of years of guilt for having loved the work of Daphne Du Maurier! Du Maurier, an English writer, had a long rich (in every way) career, beginning in the Thirties with the best seller Rebecca, and ending in 1968 with The House on the Strand, about time travel and LSD. I have read The Godfather many times, not because it is a great book, it’s not, but there is a narrative energy implicit in its pages that defies Derrida.

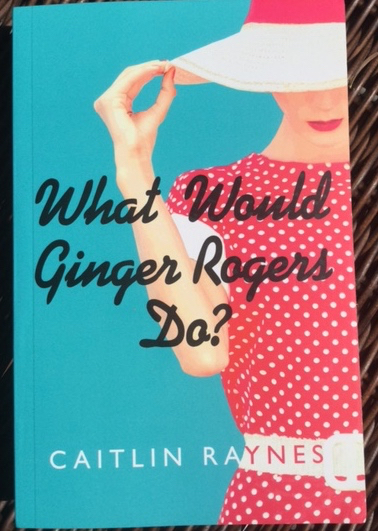

Though the Pickford Film Center lobby is not quite the confessional, still I offered up the greatest guilty pleasure of all: I had written a Beach Read. What Would Ginger Rogers Do, a light, literary confection, published last year in the UK by Buried River Press, an imprint of Robert Hale Ltd. Even the dust jacket, a feminine figure in a summer dress wearing a big hat (see above) all but shouts: Beach Read! Rom-Com! Get Out the White Wine!

Ironically, the story itself is about a bookish conflict, the mega-selling romances of an established middle aged writer, versus a gloomy-grim literary novel of rehab and suicide. The central character, Tosca Tonnino oversees Author Events at Carter &Co., a fictional bookshop in Friday Harbor. A new hire comes to the bookshop under mysterious circumstances. Ethan James, an East Coast import from a wealthy family, is attractive, secretive, sometimes surly, often blunt, occasionally witty, and fiercely competitive. Tosca finds him generally annoying until one snowy night when, thrown unexpectedly together, their romance blossoms. However, next day, Ethan makes clear, it was only a one night stand. Not long after, Tosca snags a terrific professional coup. Lucy Lamont—author of the mega-best-selling series of saccharine Shannonville novels—invites herself to do a reading at Carter &Co, June 12th. Tosca’s boss and colleagues are thrilled, but her glory is cut short. Ethan announces that his old school friend, Win Jefferies, author of Body Electric, a bleak literary bestseller, wants to come there too. June 12th. These two towering egotistical writers on the same stage? Unthinkable! The day of reckoning approaches.

Though Ginger Rogers is an eclair of a novel, I did not toss it off in a few months. On the contrary, I worked on it off and on for ten years, trying out in different forms, story, novella, novel, back to novella, return to novel. Moreover I have vast affection for it. I published it as Caitlin Raynes since the first person narrator, Tosca, is a woman about thirty; I thought my own name would undercut the narrator.

Of my three books with Robert Hale Ltd. What Would Ginger Rogers Do is the only one available in the States. Distributed, rather than published, it has languished. It needs a beach. The pages beg to be stained with SPF 50. I recommend it.

July 18, 2016

RWB Book Club: American Writers

Summer sunshine flung itself extravagantly across the Bay and puddled even on the curbside gardens across from the Pickford Film Center on July 10th, so we were a small Red Wheelbarrow Writers Book Club that afternoon, the die-hard, dedicated readers.

In honor of the Fourth of July and All-American summers, our discussion for July was American Authors, more to the point, Dead American Authors. The response was an interesting amalgam of the classic with the often overlooked. Perhaps not surprisingly many were writers who were also great adventurers. Among our choices there were no spooky New Englanders like Hawthorne, but writers who in (one way or another) sought out, embraced the world.

Frances, who grew up in South Africa, cited Carson McCullers, especially her THE HEART IS A LONELY HUNTER as having been a memorable, moving read. McCullers certainly wins the ticket for memorable titles. You’d have to look far afield to find a more enticing title than THE BALLAD OF THE SAD CAFÉ, or her more classic A MEMBER OF THE WEDDING, a title so stately and simple you are immediately drawn to read. Frances also chose another mid-century woman writer, Flannery O’Conner for her elegant array of stories and novels. For myself I prefer her stories over the novels. O’Conner’s command of scenic depiction is second to none.

Janet, who writes historical fiction, not surprisingly reached further back to Mark Twain’s ROUGHING IT, which chronicle his travels not just in Nevada and California, but in Hawaii. She also chose the work of the great American naturalist, John Muir whose books have brought the wilderness to millions of readers. The memoir of his cruel boyhood and youth is especially moving. Another adventurous author, Jack London was one of her favorites and she included too Edgar Rice Burroughs whose series of Tarzan books thrilled young readers for over a century. (Tarzan is probably the only fictional character with his own town named after him, Tarzana California, a nondescript suburb in the San Fernando Valley.)

Janet came to the book club, in 19th c regalia direct from a speaking engagement, so also on her list were the 19th c. writer known for all things Cookery and Domestic, Lydia Maria Child, a name now unfairly forgotten. And of course, Louisa May Alcott, though Janet chose to cite Alcott’s record of her nursing days during the Civil War, HOSPITAL SKETCHES, a volume I promptly went to iTunes and downloaded for free. Looking forward to reading it and wondering if her path crossed that of Walt Whitman.

Pam’s choice was the versatile May Sarton (1912—1995) poet, essayist, novelist, memorist, a keeper of journals who had a long and varied career, publishing some twenty books in EACH of these venues. She is a writer of solitude and nature, and the struggles of the creative life. She also depicted lesbian themes, notably in MRS. STEVENS HEARS THE MERMAIDS SINGING (1965) but Sarton’s range was much broader than that. Pam says at the end she was rather embittered.

Jes, who is by nature adventurous, chose that intrepid, unrepentant traveler Jack Kerouac, and also the work of Hemingway. Her favorite is his posthumously published A MOVEABLE FEAST, essays about his early years in Paris. Jes, who knows her way around a sailboat, is also fond of that ancient mariner, Herman Melville.

Marian brought titles that had always seemed to her quintessentially American when she read them growing up in the North of England. Jack London’s WHITE FANG and CALL OF THE WILD, Steinbeck’s CANNERY ROW, Salinger’s CATCHER IN THE RYE, and Lee’s TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD. As an adult reader she was entranced by Wallace Stegner’s ANGLE OF REPOSE.

I too chose some lesser known figures, starting with William Dean Howells, novelist (and Consul in Venice in the 1860’s) not much read now, but enormously influential as the editor of the ATLANTIC in the post Civil War Era. He brought the West to the East, indeed, to the world, including writers like Mark Twain and Bret Harte. At the time they were thought to be exotica, but as the choices of our book club suggest, a certain restlessness pervades American literature and Howells gave it voice. And print.

At the other end of that spectrum I offered up Van Wyck Brooks, 1886—1963 (about the same life span as William Carlos Williams) a critic and biographer who though heaped with honors throughout his life (the cover of Time Magazine, no less) spent his life desperate to identify what made literature American. He missed what was going on right under his nose! He missed the energy of Williams, Marianne Moore, John Reed, Fitzgerald, to say nothing of those rough diamonds William Faulkner and Erskine Caldwell. He published from 1905 till 1962 and never quite got it. A writer perhaps rightfully forgotten. Brooks would have been part of my dissertation had I got the PhD instead of writing my first novel.

For sheer ornery uniqueness I include James Agee, (1909—1955) chain smoker, heavy drinker, screenwriter, novelist, journalist, critic, all around genius who penned The African Queen and was awarded the Pulitzer posthumously for his unfinished, heartbreaking novel/memoir A DEATH IN THE FAMILY. His classic LET US NOW PRAISE FAMOUS MEN (1941) a photo assignment with Walker Evans, sold 600 copies before being remaindered. In 2013 the newly discovered COTTON TENANTS (from that same assignment) was published. An eccentric knockout. Part grit, part reverie, you feel the heavy hand of the southern heat and the too-soon loss of true adventurous American.

Next month in honor of August we’re convening on August 14th at the Pickford, 4 o’clock to air our guilty pleasures: BEACH READS! So dust off your fifty year old dog-eared paperback of VALLEY OF THE DOLLS and join us.

April 7, 2016

RWB March Book Club: Books of Childhood

RWB BOOK CLUB March 2016

Books of Childhood

I am now so derelict in getting this blogpost out that Childhood might well have fled, and everyone grown old. Books of Childhood was indeed the topic for our March meeting at the Pickford. We were an all female gathering of readers and this fact sparked thoughts and questions about girls reading and responding to boys adventure books.

As girls we seem to have read for adventure, never mind the boy-protagonists. RWB readers loved stories from the classic Hardy Boys to books like MY SIDE OF THE MOUNTAIN about a boy who runs away to the woods, and TREE IN THE TRAIL about the Oregon Trail. JOHNNY TREMAIN, a story of the American Revolution, was a book I so loved I memorized the whole first chapter and would recite to myself in school when I got bored (in math). At age twelve I wrote a letter to the author, Esther Forbes, suggesting she should write a sequel with Cilla, Johnny’s friend, as the central character. She very kindly wrote back and said didn’t plan to write a sequel, but if she did, she would take my suggestion.

Several RWB writers dove deep into childhood, picture books they had loved. The Little Golden Books were a staple of early childhood reading, the Babar books, as well as Madeleine, and Andersen’s fairy tales. These stories with their accompanying illustrations remain memorable to this day. And these books, still in print, we could pass on and read to our own children and grandchildren.

RWB readers too responded vividly to animal stories. CHARLIE THE TRAMP by Francis and Lillian Hoban was a particular favorite of Pam’s; Charlie is a beaver. THE LITTLE FISH THAT GOT AWAY, and especially horses and dogs including classics by Marguerite Henry, KING OF THE WIND, BLACK BEAUTY, BORN TO TROT, THE BLACK STALLION. ALL DOGS GO TO HEAVEN was an especial favorite of Jes’s, and WHITE FANG lit up Jean’s youthful reading. Linda Morrow has the fondest recollection of FERDINAND THE BULL, not so much for the story itself but because her Cuban-born mother read the book to her many times, rolling all “r’s” with Spanish pronunciation.

The adventures of PIPPI LONGSTOCKINGS illuminated the childhood of our readers and writers, and famous series: Nancy Drew, the Bobbsey Twins, the Little House books, and for Frances whose childhood was not American, but English, the Enid Blyton books, a children’s author not much read here. Lucy Montgomery’s ANNE OF GREEN GABLES was a favorite of many of us, myself included, not surprising since Anne’s great gift is her imagination and readers who grow up to be writers are themselves afflicted with imagination. (We all agreed Anne became less interesting after she grew up and married Gilbert. ‘Nuff said.)

Moving into books for slightly older kids, Pam remembered the excitement of reading ANNIE ON MY MIND about two teenage girls who fall in love, the book coming out in the ‘80’s when Pam herself was struggling with this question. Frances remembers age fourteen reading Ayn Rand and being generally disagreeable for days on end; however, Rand opened up her mind to philosophical questions and pursuits. Perhaps the most memorable childhood reading belonged to Jes whose mother was in graduate school when Jes was young, and who had on her shelf LADY CHATTERLEY’S LOVER which Jes read, even if she didn’t quite get it. Also on Mom’s shelf was a big book of American Folklore which Jes loved. Jes’s mom, it should also be noted cut up all her children’s books and put them together in an anthology of her own making calling FRIENDS OF CHILDREN. She thought her daughter would be delighted, but this was not the case.

Though as an adult I do not much like mysteries, as a kid I read through all of the books I could find by a French Canadian author, Harriett Evatt, my favorite being THE SECRET OF THE WHISPERING WILLOW. I so absorbed this book, I came home speaking French, which is to say I answered my mother with “Ooee.” A woman with four little children underfoot doesn’t have much time or patience with childhood affectations, and my mother look askance till I told her where I’d got it. Then she corrected my French. She also rolled her eyes when I took to saying “Mayhap” after reading my other favorite kids’ book, HIGHLAND REBEL, a story of Scotland in 1745, a girl having a boy’s adventure. This novel gave me a life-long love of Scotland which I passed on to my sons and their friends.

The books of childhood stay with readers forever, far longer, more intense than last year’s best seller. Just think of an entire generation of readers who will have had the brilliant shared experience of the Harry Potter novels.

February 26, 2016

Love is in the Air: RWB Book Club February

Love is in the Air

The last Valentine’s Day roses are drooping, the last of the candy down to the half-nibbled chocolates no one likes, but it’s still February. We warm up winter with stories of Love.

The RWB Book Club met, in fact, on Valentine’s Day in the lobby of the Pickford Film Center on a gusty Sunday afternoon. Fittingly, I had just come from a wedding where I had officiated. (My title: Reverend Mother.) Our theme was Love, but our readers took that theme far afield and through fiction, non fiction, and poetry, the notion of love having a far broader embrace than just romantic love. The Red Wheelbarrow Writers always have breadth and depth to their reading.

The first book recommended was an anthology of Modern Love columns from the New York Times. Daniel Jones, the editor, culled these pieces. This was an especially apt choice as several RWB writers have submitted to this column, alas, so far, without success. In this book Jones spoke of himself as “marinating in love like a pickle in vinegar,” distilling down what he has learned about love over the last nine years. Linda Lambert recommended it, read a few witty passages, but said these essays were not all of equal merit.

The philosophical among us (Frances Howard-Snyder) of course recommended Pride and Prejudice as a great love story, and also that she was now reading the book on which the film Carol was based, Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt. Frances had loved the movie and was only liking the book. And she offered that swooping story of doomed love, Brideshead Revisited.

Jes Stone brought us the work of the multi-talented Leonard Cohen, his poetry, Death of Ladies Man as an example of fantastic love poetry. Cohen also writes novels; I’ve only read his first novel, Beautiful Losers which was a beautifully written book about the polymorphously perverse, and of which I remember nothing except that phrase. Jes, having gone to Cuba this past December, also touted a love story that Cubans were mad for, Remembering Che by the second wife of Che Guevera. The writing was crappy; the book was terrible, but the Cubans loved it.

Sean Dwyer, not surprisingly had two unique titles, sci-fi writer Robert L. Heinlein’s 1956 time travel novel, The Door into Summer which is one of those books Sean returns to time and again. And an intriguing tale of a love affair between the devil and an angel called Up Jumps the Devil by Michael Poore: when the devil got kicked out of heaven, he pines for his angel girlfriend.

Susan Chase-Foster with her command of Spanish brought in a book of poems by Pablo Neruda illustrated by Pablo Picasso. They were dual-text poems, and she and Sean read a few in both English and Spanish. Everyone agreed that Neruda wrote love poetry like no one else, so rich, so intoxicating that somehow it seemed to be smothering the beloved, as though somehow to consume her. This observation began an interesting discussion of various literary/artistic lovers and the ways in which the beloved is often consumed in print, if not in life. One thinks of D. H. Lawrence and his wife Frieda, of James Joyce and Nora Barnacle, of that lovely Auden poem (the name now escapes me) where the poet realizes that his beloved has no capisce and little interest in what the poet is actually trying to accomplish, that the beloved is a rather small petulant person….and it matters not at all. Love.

Susan also mentioned a book she’s brought up before, Mary Oliver’s tribute to her longtime lover, Molly Malone, Our World.

Pam Helberg picked a nonfiction book of a different sort of love, Andrew Solomon’s 2010 Far From the Tree, the story of parents who deal with their children with disabilities, how they absorbed the truth of these disabilities, what they learned and how much they loved their children and were very grateful to have had them. A very moving book that makes the reader both think and feel.

Jennifer Wilke said that she often read love stories having seen the movie first, and the one she liked the best was The English Patient where the characters were so layered and deep. She too advocated for Leonard Cohen as a writer on love.

Leo Tolstoy came in for his share of praise in writing about love with Anna Karenina, that tragic tale, as well as War and Peace. I am an admirer of 19th century novels, so I had to bring in Jane Eyre, and then those two 19th c. novels that seem to me to be love at either end of the spectrum. Wuthering Heights for the love so tumultuous it cannot possibly endure or be in this mundane world, death seems the only answer. And Middlemarch about love in a world so mundane that it either represses or carps and snaps and bites at love’s heels. Unlike Heathcliff and Catherine, love in Middlemarch might endure, but erodes as well.

Next month, March! Magical Realism. And here is a link, thanks to Susan to start you on your reading journey: