Sergio Troncoso's Blog: Chico Lingo, by Sergio Troncoso, page 20

May 4, 2011

Obama's Focus

I like the picture released from the Situation Room, with President Barack Obama, Hilary Clinton, Robert Gates, Joe Biden and others riveted by the live screen as our Navy commandos enter Osama Bin Laden's compound in Pakistan and put a bullet in the terrorist's head. President Obama looked apprehensive, serious, and tough. But above all, focused. He took a gamble to get Bin Laden with commandos, rather than deciding to bomb the hell out of the compound. The man from Chicago would either win big or lose big.

But the gamble was a good one. The risk was commensurate with the reward: it was high risk to have our military men in harm's way, to risk a fiasco where they get killed, but it was also high reward to identify Osama Bin Laden, to kill him, and to prove to the world that the deed was truly done. What mattered was not only that our commandos were terrific, and that they completed their work without U.S. casualties. What mattered most of all was this focus. This focus from President Obama and why we were there. What 9/11 was originally about. Why we should ever risk putting our military in harm's way.

Too often, in the aftermath of 9/11, fear and paranoia were manipulated to focus on targets having little to do with what happened on that awful Tuesday in Manhattan, Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania. I experienced that awful day as a New Yorker, and it is the day I became in my heart a New Yorker. But it is also the day I began to see this country twisted by opportunists and demagogues to focus not on Al Qaeda primarily, not on Bin Laden, but on agendas having little to do with what and who wounded us so profoundly.

Why did we start a war in Iraq? For weapons of mass destruction? But they weren't there. For vague Al Qaeda connections? But the terrorists who harmed us were principally in Afghanistan, and later we now know, Pakistan. My opinion is that President Bush started the war in Iraq to finish his daddy's work, to pay back Saddam Hussein for targeting his daddy, to prosecute a personalized, blustery foreign policy that put our military in harm's way. For the wrong reasons. For the wrong target.

Hussein was a creep and a dictator, but that isn't a national security reason necessary to commit to a war. And of course, once you start a war, as Eisenhower warned us, the military-industrial complex, from generals to lobbyists to anyone else who profits from wars, will make sure the ill-begotten war continues for years, with thousands of people dead, with hundreds of billions of dollars wasted. Attempt to stop a war we should have never started in the first place, and how many right-wingers will smear you as soft on 'defense'? How many in the public will believe them? How stupidly can we keep going round and round without the right purpose?

Here was another wrong target and wrong focus. How did we allow what happened on 9/11 to be twisted first into fear about security within our borders, then into paranoia about border security, and finally into attacks against undocumented workers? We allowed idiots like Lou Dobbs to manipulate our fears into a full-throated xenophobia against anyone dark-skinned, anyone 'not like us,' anyone whom we could easily blame, anyone weak and close at hand.

We couldn't get to Bin Laden, but we could kick these Mexicans pouring concrete on our sidewalks and slaving away for pennies, yes we could kick them in the ass and feel good about ourselves. It might have been false, this feel-good kick, but it was something, and it was what we had. How many of us stepped up, said no, and yelled at the xenophobes, to tell them they had the wrong target? How many pointed out that our lack of work ethic, and our lack of focus on educating our kids, and our adoration of a superficial, materialistic culture were primarily to blame for our not competing effectively against nations like China? Believe me, right now dying Detroit could be revived if civic leaders just rolled out the red carpet for one million, hard-working, undocumented Mexicans.

Obama, in that picture from the Situation Room, was focused. He was focused on the right target. He was focused on what should have been the target all along. Al Qaeda, and all it represents. Period. Now that this commando mission has been completed successfully, perhaps we in the United States can start focusing on our problems straight on. Our real problems. Not our prejudices. Not our fantasies. Not our petty vendettas. But the problems that matter. To solve them, to make us a better country, to overcome even the worst of our days.

www.ChicoLingo.com

But the gamble was a good one. The risk was commensurate with the reward: it was high risk to have our military men in harm's way, to risk a fiasco where they get killed, but it was also high reward to identify Osama Bin Laden, to kill him, and to prove to the world that the deed was truly done. What mattered was not only that our commandos were terrific, and that they completed their work without U.S. casualties. What mattered most of all was this focus. This focus from President Obama and why we were there. What 9/11 was originally about. Why we should ever risk putting our military in harm's way.

Too often, in the aftermath of 9/11, fear and paranoia were manipulated to focus on targets having little to do with what happened on that awful Tuesday in Manhattan, Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania. I experienced that awful day as a New Yorker, and it is the day I became in my heart a New Yorker. But it is also the day I began to see this country twisted by opportunists and demagogues to focus not on Al Qaeda primarily, not on Bin Laden, but on agendas having little to do with what and who wounded us so profoundly.

Why did we start a war in Iraq? For weapons of mass destruction? But they weren't there. For vague Al Qaeda connections? But the terrorists who harmed us were principally in Afghanistan, and later we now know, Pakistan. My opinion is that President Bush started the war in Iraq to finish his daddy's work, to pay back Saddam Hussein for targeting his daddy, to prosecute a personalized, blustery foreign policy that put our military in harm's way. For the wrong reasons. For the wrong target.

Hussein was a creep and a dictator, but that isn't a national security reason necessary to commit to a war. And of course, once you start a war, as Eisenhower warned us, the military-industrial complex, from generals to lobbyists to anyone else who profits from wars, will make sure the ill-begotten war continues for years, with thousands of people dead, with hundreds of billions of dollars wasted. Attempt to stop a war we should have never started in the first place, and how many right-wingers will smear you as soft on 'defense'? How many in the public will believe them? How stupidly can we keep going round and round without the right purpose?

Here was another wrong target and wrong focus. How did we allow what happened on 9/11 to be twisted first into fear about security within our borders, then into paranoia about border security, and finally into attacks against undocumented workers? We allowed idiots like Lou Dobbs to manipulate our fears into a full-throated xenophobia against anyone dark-skinned, anyone 'not like us,' anyone whom we could easily blame, anyone weak and close at hand.

We couldn't get to Bin Laden, but we could kick these Mexicans pouring concrete on our sidewalks and slaving away for pennies, yes we could kick them in the ass and feel good about ourselves. It might have been false, this feel-good kick, but it was something, and it was what we had. How many of us stepped up, said no, and yelled at the xenophobes, to tell them they had the wrong target? How many pointed out that our lack of work ethic, and our lack of focus on educating our kids, and our adoration of a superficial, materialistic culture were primarily to blame for our not competing effectively against nations like China? Believe me, right now dying Detroit could be revived if civic leaders just rolled out the red carpet for one million, hard-working, undocumented Mexicans.

Obama, in that picture from the Situation Room, was focused. He was focused on the right target. He was focused on what should have been the target all along. Al Qaeda, and all it represents. Period. Now that this commando mission has been completed successfully, perhaps we in the United States can start focusing on our problems straight on. Our real problems. Not our prejudices. Not our fantasies. Not our petty vendettas. But the problems that matter. To solve them, to make us a better country, to overcome even the worst of our days.

www.ChicoLingo.com

Published on May 04, 2011 03:39

March 31, 2011

Work@Character

Yesterday Laura and I had our last face-to-face teacher conference of the academic year for our younger son Isaac. Next year he will join his older brother at one of the best high schools in New York City, and this conference was bittersweet for us.

Both our children attended the Bank Street School for Children starting as three-year-olds. Aaron graduated two years ago, and I'm on the parents' committee for Isaac's graduation in two months. Bank Street has been a remarkable school for both our children, and it will be hard to leave it.

But what struck me was how Laura and I reached this point, with two similar, yet also different kids, both who work hard and possess unique abilities, but who also needed to overcome specific challenges. My kids are excellent students at their schools; they have scored at the highest levels in standardized tests to reach their goals. Both are avid readers of very different books, yet Aaron and Isaac share a sense of humor that is light years beyond mine. Do I even have a sense of humor? I am their strict, mercurial father.

What is obscured by this bit of bragging about my kids —who are not kids anymore but young adults— is the years of hard work of parenting to help Aaron and Isaac become the best version of themselves. I believe in learning by doing, Bank Street's philosophy, but also Aristotle's. I never did my children's homework. On the contrary, in recent years, I have hardly seen what they have worked on after coming home from school. But when they have a question or a problem, I teach them how to find the answer for themselves. When they are stuck, I prompt them with questions to guide them to their own revelations.

We provide the space and time to focus quietly on their schoolwork. Friends who are wild or rude, I tell my kids, are not welcomed in our home. When Aaron and Isaac start wavering on the good habits we have encouraged, when they watch too much TV, or have not chosen the next book to read in bed, then yes, I am the heavy. I draw the bright line too many parents fail to draw: to turn off the TV, or to make finding a new book a priority, or to rewrite what they thought was 'good enough.' Real pride in your work is when you learn to do it yourself —not when somebody else does it for you— and when you know the work you accomplished was excellent. But often children have to be guided to get there.

Case in point. A few weeks ago, Isaac had brought home two short papers in which the teachers had given him only average marks. Isaac knew it wasn't very good work, and he showed me the papers with what seemed a mix of fear and shame in his eyes. I read the papers, and yes, they were lightly researched, and his arguments were unsupported and often unclear. I remembered when he had worked on these papers, and I knew he had not given them the time they required, or the focus. Isaac is a bright kid and a good writer, but perhaps that week he had worried too much about succeeding at Oblivion on the Xbox, and too little about the failures of Reconstruction after the Civil War.

We talked about it, and we decided he would ask his teachers if he could rewrite both papers over the following two weeks of Spring Break. I told him it didn't matter if his teachers didn't give him different grades, but what did matter was that he should do his best work. And this wasn't his best work, was it? No, he said, it wasn't. Yes, I was a bit the heavy. I also told Isaac he wouldn't play the Xbox over Spring Break, nor watch any TV, until those papers were rewritten, and well.

Isaac asked his teachers about rewriting the essays on the Friday before Spring Break, and they agreed. The teachers also decided to extend that offer to all the kids in the class: if anybody else wanted to rewrite their papers, they could. But, as far as I know, only Isaac would rewrite his papers during this vacation.

Now let me tell you about what happened over Spring Break. Isaac worked from morning until afternoon, for five days straight, rereading and expanding his source material, outlining his arguments, and reconstructing his essays. Sometimes he would ask questions. Occasionally he showed me what he had written, and I gave him my honest opinion. He rewrote page after page.

Whether he was motivated by his desire to get to Oblivion before his vacation ended, to please his mean old father, to show the teachers what he could do, or a combination of these, I don't know. But Isaac worked independently, and ferociously. I was in awe, and prouder than any father could be.

Weeks later, at the conference, Isaac's teachers noted how remarkably better the second go-around of his Civil War papers had been. They had given Isaac the highest marks for his rewrites. That was the work they had been accustomed to seeing from Isaac. Moreover, the teachers happily noted that on an in-class essay after Spring Break Isaac had again written a beautifully coherent essay on the Civil Rights movement.

Perhaps the teachers suspected that I, the writer-father, had 'helped' him on the rewrites during Spring Break, but the in-class essay confirmed it was Isaac who had done the work on the rewrites. And indeed it was. I just set the bar high. I did not allow him to lower it because I knew he could reach it. I gave my son advice to prompt him to think for himself when he needed it. Isaac learned by doing it, the hard way, the only way. The way toward good character.

www.ChicoLingo.com

Both our children attended the Bank Street School for Children starting as three-year-olds. Aaron graduated two years ago, and I'm on the parents' committee for Isaac's graduation in two months. Bank Street has been a remarkable school for both our children, and it will be hard to leave it.

But what struck me was how Laura and I reached this point, with two similar, yet also different kids, both who work hard and possess unique abilities, but who also needed to overcome specific challenges. My kids are excellent students at their schools; they have scored at the highest levels in standardized tests to reach their goals. Both are avid readers of very different books, yet Aaron and Isaac share a sense of humor that is light years beyond mine. Do I even have a sense of humor? I am their strict, mercurial father.

What is obscured by this bit of bragging about my kids —who are not kids anymore but young adults— is the years of hard work of parenting to help Aaron and Isaac become the best version of themselves. I believe in learning by doing, Bank Street's philosophy, but also Aristotle's. I never did my children's homework. On the contrary, in recent years, I have hardly seen what they have worked on after coming home from school. But when they have a question or a problem, I teach them how to find the answer for themselves. When they are stuck, I prompt them with questions to guide them to their own revelations.

We provide the space and time to focus quietly on their schoolwork. Friends who are wild or rude, I tell my kids, are not welcomed in our home. When Aaron and Isaac start wavering on the good habits we have encouraged, when they watch too much TV, or have not chosen the next book to read in bed, then yes, I am the heavy. I draw the bright line too many parents fail to draw: to turn off the TV, or to make finding a new book a priority, or to rewrite what they thought was 'good enough.' Real pride in your work is when you learn to do it yourself —not when somebody else does it for you— and when you know the work you accomplished was excellent. But often children have to be guided to get there.

Case in point. A few weeks ago, Isaac had brought home two short papers in which the teachers had given him only average marks. Isaac knew it wasn't very good work, and he showed me the papers with what seemed a mix of fear and shame in his eyes. I read the papers, and yes, they were lightly researched, and his arguments were unsupported and often unclear. I remembered when he had worked on these papers, and I knew he had not given them the time they required, or the focus. Isaac is a bright kid and a good writer, but perhaps that week he had worried too much about succeeding at Oblivion on the Xbox, and too little about the failures of Reconstruction after the Civil War.

We talked about it, and we decided he would ask his teachers if he could rewrite both papers over the following two weeks of Spring Break. I told him it didn't matter if his teachers didn't give him different grades, but what did matter was that he should do his best work. And this wasn't his best work, was it? No, he said, it wasn't. Yes, I was a bit the heavy. I also told Isaac he wouldn't play the Xbox over Spring Break, nor watch any TV, until those papers were rewritten, and well.

Isaac asked his teachers about rewriting the essays on the Friday before Spring Break, and they agreed. The teachers also decided to extend that offer to all the kids in the class: if anybody else wanted to rewrite their papers, they could. But, as far as I know, only Isaac would rewrite his papers during this vacation.

Now let me tell you about what happened over Spring Break. Isaac worked from morning until afternoon, for five days straight, rereading and expanding his source material, outlining his arguments, and reconstructing his essays. Sometimes he would ask questions. Occasionally he showed me what he had written, and I gave him my honest opinion. He rewrote page after page.

Whether he was motivated by his desire to get to Oblivion before his vacation ended, to please his mean old father, to show the teachers what he could do, or a combination of these, I don't know. But Isaac worked independently, and ferociously. I was in awe, and prouder than any father could be.

Weeks later, at the conference, Isaac's teachers noted how remarkably better the second go-around of his Civil War papers had been. They had given Isaac the highest marks for his rewrites. That was the work they had been accustomed to seeing from Isaac. Moreover, the teachers happily noted that on an in-class essay after Spring Break Isaac had again written a beautifully coherent essay on the Civil Rights movement.

Perhaps the teachers suspected that I, the writer-father, had 'helped' him on the rewrites during Spring Break, but the in-class essay confirmed it was Isaac who had done the work on the rewrites. And indeed it was. I just set the bar high. I did not allow him to lower it because I knew he could reach it. I gave my son advice to prompt him to think for himself when he needed it. Isaac learned by doing it, the hard way, the only way. The way toward good character.

www.ChicoLingo.com

Published on March 31, 2011 06:05

February 20, 2011

Packinghouse Poet

I have spent the last week delightfully immersed in the poetry of David Dominguez, who wrote

The Ghost of César Chávez

and

Work Done Right

. David is also co-founder and poetry editor of

The Packinghouse Review

from California's San Joaquin Valley. You should read this poet.

His narrative poetry struck multiple chords with me. His images of working at Galdini Sausage grinding pork, driving his red pickup across the California desert, and even setting the tile floor for his new house were evocative. They reminded me of where I started in Ysleta, how I worked on Texas farms as a child, and how I hated the poverty of this existence yet how it also defined who I was. There is a certain pride in work and in your body throbbing beyond any boundaries you imagined you could endure. You identify with those who come home with pieces of pork fat wedged into their boots, with gashes on their arms and legs from their tools and machines, and with black grime etched into the folds of their dark skin.

Too often this country has turned its back on the working class and the working poor, not to mention the undocumented workers who harvest the food for American tables and build our houses. We idolize Warren Buffett and the culture of wealth. However, we don't realize that what is most radically proscribed for profitable companies and a profitable business climate often means monopolistic or oligopolistic pricing power and predatory practices against hapless, powerless consumers.

What is best is a balance, between making money for entrepreneurs and their companies, and also providing beneficial products and services for consumers, with protections against abuses. I think we have lost that balance in this country. The richest of the rich have dramatically increased their share of the nation's income, while the bottom sixty percent of this country —yes the majority of the people— have seen their share of income shrink in the past thirty years. Worse yet, multitudes have been convinced we need even less protection from the abuses of Wall Street, that we need to give more tax breaks to businesses and the super-wealthy, and that somehow these policies will rain money on the plebes below and return the United States to an idealized past glory. Good luck with that.

But I digress, yet only slightly. David Dominguez's poetry brings us back to a focus on the working man, the pride and heartache of work, and the heritage of our families, Chicano and Mexicano. This is what I think good literature should be: expertly crafted lines, unique images that spur thinking, and…and…a focus against the grain, against what society stupidly values, a view that unsettles our comfortable perspectives. This kind of good literature fights against our über-focus on 'material success equals what is worthy,' which infected the literary world long ago and transformed 'what is good' in books into only 'what is entertaining,' escapism for the masses.

What I believe propels David Dominguez's poetry even a step further is his introspection, and how his success as a writer and teacher has left him in an ambiguous place beyond obreros, beyond his father and grandfather, yet not quite an Americano:

At the register, the cashier glanced at my blazer."This it?" she asked, not "Hola, señor."Once, after weeding and hoeing my flower beds all day,I came here to buy insecticide and Roundup,and the same cashier asked me, "Cómo le va, señor?"Like many, I prefer Macy's over the swap meetand would rather play a round of golfalongside the wet eucalyptus clinging to the riverbankthan rise every morning to mow lawnsor gather with others on street corners,praying for the chance to hop into trucks as underpaidconstruction workers building housing tracts.I'm spoken to informally in English if I'm cleanbut in Spanish if I'm sweaty and dirty.It happens all the time; I could bet on it:the odds are as reliable as rope.

This strange, in-between existence has certainly been central to my life. To succeed in the American literary world, you must write in English, perfectly and singularly. You must appeal to what most literary buyers want to read (or at least a significant number of readers), and that often has nothing to do with obreros, or Chicanos, or issues that criticize the mainstream. You must appeal to the lowest common denominator in this culture, and that is 'entertainment that transports you somewhere, without making you think too much, without being too complex.' As you, the writer, push forward into American culture (should you?), are you leaving more of yourself behind? Who were you anyway? Who should you be? These questions have no easy answers.

www.ChicoLingo.com

His narrative poetry struck multiple chords with me. His images of working at Galdini Sausage grinding pork, driving his red pickup across the California desert, and even setting the tile floor for his new house were evocative. They reminded me of where I started in Ysleta, how I worked on Texas farms as a child, and how I hated the poverty of this existence yet how it also defined who I was. There is a certain pride in work and in your body throbbing beyond any boundaries you imagined you could endure. You identify with those who come home with pieces of pork fat wedged into their boots, with gashes on their arms and legs from their tools and machines, and with black grime etched into the folds of their dark skin.

Too often this country has turned its back on the working class and the working poor, not to mention the undocumented workers who harvest the food for American tables and build our houses. We idolize Warren Buffett and the culture of wealth. However, we don't realize that what is most radically proscribed for profitable companies and a profitable business climate often means monopolistic or oligopolistic pricing power and predatory practices against hapless, powerless consumers.

What is best is a balance, between making money for entrepreneurs and their companies, and also providing beneficial products and services for consumers, with protections against abuses. I think we have lost that balance in this country. The richest of the rich have dramatically increased their share of the nation's income, while the bottom sixty percent of this country —yes the majority of the people— have seen their share of income shrink in the past thirty years. Worse yet, multitudes have been convinced we need even less protection from the abuses of Wall Street, that we need to give more tax breaks to businesses and the super-wealthy, and that somehow these policies will rain money on the plebes below and return the United States to an idealized past glory. Good luck with that.

But I digress, yet only slightly. David Dominguez's poetry brings us back to a focus on the working man, the pride and heartache of work, and the heritage of our families, Chicano and Mexicano. This is what I think good literature should be: expertly crafted lines, unique images that spur thinking, and…and…a focus against the grain, against what society stupidly values, a view that unsettles our comfortable perspectives. This kind of good literature fights against our über-focus on 'material success equals what is worthy,' which infected the literary world long ago and transformed 'what is good' in books into only 'what is entertaining,' escapism for the masses.

What I believe propels David Dominguez's poetry even a step further is his introspection, and how his success as a writer and teacher has left him in an ambiguous place beyond obreros, beyond his father and grandfather, yet not quite an Americano:

At the register, the cashier glanced at my blazer."This it?" she asked, not "Hola, señor."Once, after weeding and hoeing my flower beds all day,I came here to buy insecticide and Roundup,and the same cashier asked me, "Cómo le va, señor?"Like many, I prefer Macy's over the swap meetand would rather play a round of golfalongside the wet eucalyptus clinging to the riverbankthan rise every morning to mow lawnsor gather with others on street corners,praying for the chance to hop into trucks as underpaidconstruction workers building housing tracts.I'm spoken to informally in English if I'm cleanbut in Spanish if I'm sweaty and dirty.It happens all the time; I could bet on it:the odds are as reliable as rope.

This strange, in-between existence has certainly been central to my life. To succeed in the American literary world, you must write in English, perfectly and singularly. You must appeal to what most literary buyers want to read (or at least a significant number of readers), and that often has nothing to do with obreros, or Chicanos, or issues that criticize the mainstream. You must appeal to the lowest common denominator in this culture, and that is 'entertainment that transports you somewhere, without making you think too much, without being too complex.' As you, the writer, push forward into American culture (should you?), are you leaving more of yourself behind? Who were you anyway? Who should you be? These questions have no easy answers.

www.ChicoLingo.com

Published on February 20, 2011 17:50

January 31, 2011

Moral luck

This week something strange happened to me. I was in an elevator in my co-op, and I got stuck. All four elevators in my 23-story building were replaced last year, at a significant cost to shareholders. Yet the expense was necessary, because the old ones had begun to fail too often. The news elevators were speedy, and after a few kinks had been worked out last year, they were running smoothly. Until I stepped into elevator No. 3.

I got into the elevator on my floor, and was headed toward the lobby. I pressed L, and the door closed, but the elevator did not move. The door opened again on my floor. I pressed L again, and the door closed, but the elevator did not move. One more time. Of course, this should have been my clue to take another elevator, but I am a stubborn human being. This time it cost me.

On the third try, the L button remained lit, and the elevator started to descend. At about the fifteenth floor, it stopped. The door did not open, the L button was still lit, and I was stuck. I pressed the button for the third floor, to see if that would prompt the elevator to move. It did not. I pressed the phone button on the elevator panel, but no one picked up at the front desk, and now I was peeved. I wasn't nervous. I just thought, "This stupid contraption is wasting my time. How much did we pay for this thing?"

On the third try, the L button remained lit, and the elevator started to descend. At about the fifteenth floor, it stopped. The door did not open, the L button was still lit, and I was stuck. I pressed the button for the third floor, to see if that would prompt the elevator to move. It did not. I pressed the phone button on the elevator panel, but no one picked up at the front desk, and now I was peeved. I wasn't nervous. I just thought, "This stupid contraption is wasting my time. How much did we pay for this thing?"

I called our concierge on my cell phone, and Vinnie picked up immediately. He said the mechanic had been working on elevator No. 3 and was about to leave. Vinnie grumbled something about the need for better elevator mechanics. He told me not to worry, that they would get me out in a few minutes.

I stepped away from the elevator panel, and reclined against a corner. I was alone, but perhaps I could check my email, I thought. I did notice the four walls around me, the painfully bright miniature elevator lights above my head, and a rising tension in my throat, but I quelled my own imminent claustrophobia by scrolling through my email on my beloved iPhone. After about ten or fifteen minutes, my forehead was damp, but I was still okay. Vaguely I could hear the mechanic on the other side of the door, perhaps a floor above or below me. I didn't even know on what floor I was stuck.

Suddenly the elevator moved. It descended I would guess about two floors, and then braked hard to a stop. I was getting angry. Again it moved, and again it stopped abruptly, as if the emergency brakes had been automatically applied. On the third time the elevator moved and stopped without rhyme or reason, the doors popped open on the third floor, and I jumped out, relieved.

A handyman from our building asked me if I was okay, and I said that I was, although I felt dizzy. As I walked from the lobby onto Broadway, my head didn't feel right. I had errands to do, groceries to buy, manuscripts to send out, and I did all those things, but within an hour after my elevator incident I felt as if someone had kicked me in the head twice. Perhaps those jolts in the elevator had been more severe than I had imagined. I wondered how my brain had sloshed inside my head as the elevator dropped and jolted to a stop twice.

After two hours, I had to lie down. It took about half a day to get my bearings again, to rid myself of being lightheaded.

Days later, I am fine. Don't worry, dear reader. I'll imagine you worried, even though you didn't. It just makes me feel better to think that, and sometimes you need to do whatever gets you back on track, even if it is only with your imagination.

Today, as I was walking home with my son after his tennis lesson, a woman who was texting as she drove a shiny SUV, narrowly missed us on a crosswalk on Broadway. Well, narrowly missed my son. I put my hand to his chest and stopped him, having eyed the driver and her fingers furiously working her little gadget over the steering wheel. How do we ever survive in this world? With a little luck, and sometimes a little help.

www.ChicoLingo.com

I got into the elevator on my floor, and was headed toward the lobby. I pressed L, and the door closed, but the elevator did not move. The door opened again on my floor. I pressed L again, and the door closed, but the elevator did not move. One more time. Of course, this should have been my clue to take another elevator, but I am a stubborn human being. This time it cost me.

On the third try, the L button remained lit, and the elevator started to descend. At about the fifteenth floor, it stopped. The door did not open, the L button was still lit, and I was stuck. I pressed the button for the third floor, to see if that would prompt the elevator to move. It did not. I pressed the phone button on the elevator panel, but no one picked up at the front desk, and now I was peeved. I wasn't nervous. I just thought, "This stupid contraption is wasting my time. How much did we pay for this thing?"

On the third try, the L button remained lit, and the elevator started to descend. At about the fifteenth floor, it stopped. The door did not open, the L button was still lit, and I was stuck. I pressed the button for the third floor, to see if that would prompt the elevator to move. It did not. I pressed the phone button on the elevator panel, but no one picked up at the front desk, and now I was peeved. I wasn't nervous. I just thought, "This stupid contraption is wasting my time. How much did we pay for this thing?"I called our concierge on my cell phone, and Vinnie picked up immediately. He said the mechanic had been working on elevator No. 3 and was about to leave. Vinnie grumbled something about the need for better elevator mechanics. He told me not to worry, that they would get me out in a few minutes.

I stepped away from the elevator panel, and reclined against a corner. I was alone, but perhaps I could check my email, I thought. I did notice the four walls around me, the painfully bright miniature elevator lights above my head, and a rising tension in my throat, but I quelled my own imminent claustrophobia by scrolling through my email on my beloved iPhone. After about ten or fifteen minutes, my forehead was damp, but I was still okay. Vaguely I could hear the mechanic on the other side of the door, perhaps a floor above or below me. I didn't even know on what floor I was stuck.

Suddenly the elevator moved. It descended I would guess about two floors, and then braked hard to a stop. I was getting angry. Again it moved, and again it stopped abruptly, as if the emergency brakes had been automatically applied. On the third time the elevator moved and stopped without rhyme or reason, the doors popped open on the third floor, and I jumped out, relieved.

A handyman from our building asked me if I was okay, and I said that I was, although I felt dizzy. As I walked from the lobby onto Broadway, my head didn't feel right. I had errands to do, groceries to buy, manuscripts to send out, and I did all those things, but within an hour after my elevator incident I felt as if someone had kicked me in the head twice. Perhaps those jolts in the elevator had been more severe than I had imagined. I wondered how my brain had sloshed inside my head as the elevator dropped and jolted to a stop twice.

After two hours, I had to lie down. It took about half a day to get my bearings again, to rid myself of being lightheaded.

Days later, I am fine. Don't worry, dear reader. I'll imagine you worried, even though you didn't. It just makes me feel better to think that, and sometimes you need to do whatever gets you back on track, even if it is only with your imagination.

Today, as I was walking home with my son after his tennis lesson, a woman who was texting as she drove a shiny SUV, narrowly missed us on a crosswalk on Broadway. Well, narrowly missed my son. I put my hand to his chest and stopped him, having eyed the driver and her fingers furiously working her little gadget over the steering wheel. How do we ever survive in this world? With a little luck, and sometimes a little help.

www.ChicoLingo.com

Published on January 31, 2011 18:20

December 22, 2010

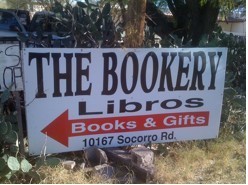

The Bookery in Socorro

After buying asaderos at Licon's Dairy, I drove Laura, Aaron, and Isaac to one of my favorite independent bookstores, The Bookery in Socorro, on the east side of El Paso. The Bookery is walking distance from the historic Socorro Mission, one of the three missions on the Mission Trail.

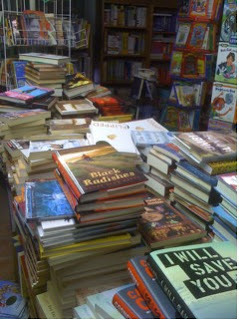

After buying asaderos at Licon's Dairy, I drove Laura, Aaron, and Isaac to one of my favorite independent bookstores, The Bookery in Socorro, on the east side of El Paso. The Bookery is walking distance from the historic Socorro Mission, one of the three missions on the Mission Trail. The Bookery is an adobe labyrinth stuffed with books on tables, books on the floor, books overflowing on bookshelves. It is easily the best place for buying Latino literature in El Paso, but this bookstore has so much more: young adult books, history books on El Paso and the Southwest, hundreds of picture books for kids, a menagerie of stuffed animals, Mexican calacas, Christmas decorations, trinkets hanging from vigas on the ceiling. After a dusty trek through the desert, I feel as if I've walked into a treasure room whenever I visit The Bookery.

The Bookery is an adobe labyrinth stuffed with books on tables, books on the floor, books overflowing on bookshelves. It is easily the best place for buying Latino literature in El Paso, but this bookstore has so much more: young adult books, history books on El Paso and the Southwest, hundreds of picture books for kids, a menagerie of stuffed animals, Mexican calacas, Christmas decorations, trinkets hanging from vigas on the ceiling. After a dusty trek through the desert, I feel as if I've walked into a treasure room whenever I visit The Bookery. But as I chatted with Margaret Barber, longtime owner, I worried. She told me this has been her toughest year financially. Of course, her bookstore has suffered as most of the book industry has suffered. People are reading less. Young adults, and others, prefer to download books electronically, rather than holding books in their hands.

But as I chatted with Margaret Barber, longtime owner, I worried. She told me this has been her toughest year financially. Of course, her bookstore has suffered as most of the book industry has suffered. People are reading less. Young adults, and others, prefer to download books electronically, rather than holding books in their hands.To add to Margaret's troubles, some in El Paso confused the closing of another wonderful bookstore, the Book Gallery, with The Bookery. School districts and teachers stopped ordering from The Bookery, with the assumption that The Bookery had closed. Yes, the Book Gallery in El Paso closed (alas), but The Bookery in Socorro is still open, and alive. We need to support it.

Where else can you find an owner who has read hundreds of the books she sells? Who will sit with you on her porch under the rough-hewn vigas, offer you coffee, and talk about books, and the famous writers who have visited her store, and the scuttlebutt of the neighborhood? Margaret is unstintingly honest, and will pointedly let you know when an author, or his or her work, is not up to snuff in her estimation. Isn't that what everyone wants, an honest opinion? Don't you want to be introduced to a new author, or pointed in a new literary direction, by a book lover who possesses an uncanny memory? Let me tell you, you don't get a Margaret Barber on Amazon, and you don't get her at Barnes and Noble. You get her only at The Bookery.

I hope if you are shopping for the holidays, or if you are savoring warm asaderos from Licon's Dairy, or if you yearn for an afternoon of intelligent, irreverent conversation about books, that you will hit the brakes at The Bookery on Socorro Road. We need independent bookstores, we need independent voices, we need people thinking and arguing passionately about what should be in your brain, and why. What we don't need is more homogenization, or mass-market brainwashing.

I hope if you are shopping for the holidays, or if you are savoring warm asaderos from Licon's Dairy, or if you yearn for an afternoon of intelligent, irreverent conversation about books, that you will hit the brakes at The Bookery on Socorro Road. We need independent bookstores, we need independent voices, we need people thinking and arguing passionately about what should be in your brain, and why. What we don't need is more homogenization, or mass-market brainwashing.To open up your mind, go to The Bookery on El Paso's historic Mission Trail, at 10167 Socorro Road. Margaret's phone number is 915-859-6132. From I-10, you get off at Americas Avenue, follow Americas (Loop 375) until you get to Socorro Road, and then head east. As soon as you pass the Socorro Mission, The Bookery is on the left side. It is one of those places worth fighting for.

www.ChicoLingo.com

Published on December 22, 2010 21:19

December 15, 2010

The Provinciality of the United States

Literal Magazine: Latin American Voices

continues to be a provocative voice in culture, literature, and politics. One of the best things about publishing your work in a magazine such as Literal ("How Has the Loss of Juárez Changed Border Culture?") is to read who else is in the issue. What fascinated me were two interviews, with the Mexican author Carlos Fuentes and philosopher Martha Nussbaum.

Two quotes in particular resonated with me:

"What's going on is that this country, the United States, has become very provincial. When I started out, my editors, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, were publishing Francois Mauriac, Alberto Moravia, and ten or fifteen foreign novelists. Now there's no one. Those of us who have been established for a long time, like Gabriel García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, or myself, have kept on publishing, but almost out of condescendence. There is no interest in new writers, in the vast quantity and quality of writers we have in Hispanic America. This country has become very self- absorbed and preoccupied, and it still does not understand what is going on in the world." –Carlos Fuentes

"What's going on is that this country, the United States, has become very provincial. When I started out, my editors, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, were publishing Francois Mauriac, Alberto Moravia, and ten or fifteen foreign novelists. Now there's no one. Those of us who have been established for a long time, like Gabriel García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, or myself, have kept on publishing, but almost out of condescendence. There is no interest in new writers, in the vast quantity and quality of writers we have in Hispanic America. This country has become very self- absorbed and preoccupied, and it still does not understand what is going on in the world." –Carlos Fuentes

"I still believe that a healthy democracy needs an education that focuses on (1) Socratic self-examination and critical thinking; (2) the capacity to think as a citizen of the whole world, not just some local region or group, in a way informed by adequate historical, economic, and religious knowledge; and (3) trained imaginative capacities, so that people can put themselves in the position of others whose ways of life are very different from their own." –Martha Nussbaum

For many reasons, what Fuentes and Nussbaum were saying hit home. I have seen how little U. S. readers read in translation, or how rarely they seek out foreign writers in their own language, be it Spanish, Chinese or German, and so on. Pundits and politicos have also narrowed their agendas and appeals, to forego fact-checking, to trumpet narrow-minded biases. What is routinely ignored is a more expansive appeal to the public to appreciate working in someone else's shoes, for example, particularly one who is dark-skinned and has an accent.

The United States suffers from a growing deficit of imagination. Not just for humanism. Not for embracing a Kumbaya moment of idealism. But for the truth. Even my thirteen-year-old knows that to better understand your position and your argument —he learned that in mock Supreme Court cases his class studied and debated— you need to 'see' the other side. The critical thinking of Socrates is based on answering questions that unmoor you, and probing your opponent with similar questions, but all of this 'education' is based on souls being open to such give-and-take. What happens when we as a society become more insular? What happens when we stop reading to challenge ourselves? When we don't care enough to question our own thinking?

These questions mattered in a writing group in which I recently participated. One story I submitted was set on the Mexican-American border, and although the story received many favorable, enthusiastic comments, two or three in the group pointedly had an issue with my use of Spanish phrases and sentences intermixed with my prose in English. Didn't I want to expand my readership? they asked. Wasn't I limiting myself as a writer by excluding people like them who didn't understand Spanish? (We were talking about four or five sentences in story that was 28 pages long.)

I was blunt and unapologetic. I told them New York readers were at the end of my line, in terms of the readers I was focusing on. I wanted to be authentic to the setting, the Mexican-American border. I asked them how many had read Vargas Llosa, or Paz, or García Márquez in Spanish? How many of them had stepped outside their comfortable linguistic boxes, to seek truth in other worlds and other languages? I mentioned how I had learned German to read Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Mann in the original. Perhaps I was too harsh on my fellow writers. But even in cosmopolitan Manhattan, among the educated, our provincialism is growing. But at what cost, and why?

What happens when a society stops caring about the hard work of imagination, self-criticism, and education? Will it even realize what it has lost? This season, give someone you care about a book in translation, prose or poetry from a university press, or point them to other indie favorites, in magazines or the like. Broaden their minds, and prompt their critical thinking. Help our citizens earn their place in this democracy.

www.ChicoLingo.com

Two quotes in particular resonated with me:

"What's going on is that this country, the United States, has become very provincial. When I started out, my editors, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, were publishing Francois Mauriac, Alberto Moravia, and ten or fifteen foreign novelists. Now there's no one. Those of us who have been established for a long time, like Gabriel García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, or myself, have kept on publishing, but almost out of condescendence. There is no interest in new writers, in the vast quantity and quality of writers we have in Hispanic America. This country has become very self- absorbed and preoccupied, and it still does not understand what is going on in the world." –Carlos Fuentes

"What's going on is that this country, the United States, has become very provincial. When I started out, my editors, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, were publishing Francois Mauriac, Alberto Moravia, and ten or fifteen foreign novelists. Now there's no one. Those of us who have been established for a long time, like Gabriel García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, or myself, have kept on publishing, but almost out of condescendence. There is no interest in new writers, in the vast quantity and quality of writers we have in Hispanic America. This country has become very self- absorbed and preoccupied, and it still does not understand what is going on in the world." –Carlos Fuentes"I still believe that a healthy democracy needs an education that focuses on (1) Socratic self-examination and critical thinking; (2) the capacity to think as a citizen of the whole world, not just some local region or group, in a way informed by adequate historical, economic, and religious knowledge; and (3) trained imaginative capacities, so that people can put themselves in the position of others whose ways of life are very different from their own." –Martha Nussbaum

For many reasons, what Fuentes and Nussbaum were saying hit home. I have seen how little U. S. readers read in translation, or how rarely they seek out foreign writers in their own language, be it Spanish, Chinese or German, and so on. Pundits and politicos have also narrowed their agendas and appeals, to forego fact-checking, to trumpet narrow-minded biases. What is routinely ignored is a more expansive appeal to the public to appreciate working in someone else's shoes, for example, particularly one who is dark-skinned and has an accent.

The United States suffers from a growing deficit of imagination. Not just for humanism. Not for embracing a Kumbaya moment of idealism. But for the truth. Even my thirteen-year-old knows that to better understand your position and your argument —he learned that in mock Supreme Court cases his class studied and debated— you need to 'see' the other side. The critical thinking of Socrates is based on answering questions that unmoor you, and probing your opponent with similar questions, but all of this 'education' is based on souls being open to such give-and-take. What happens when we as a society become more insular? What happens when we stop reading to challenge ourselves? When we don't care enough to question our own thinking?

These questions mattered in a writing group in which I recently participated. One story I submitted was set on the Mexican-American border, and although the story received many favorable, enthusiastic comments, two or three in the group pointedly had an issue with my use of Spanish phrases and sentences intermixed with my prose in English. Didn't I want to expand my readership? they asked. Wasn't I limiting myself as a writer by excluding people like them who didn't understand Spanish? (We were talking about four or five sentences in story that was 28 pages long.)

I was blunt and unapologetic. I told them New York readers were at the end of my line, in terms of the readers I was focusing on. I wanted to be authentic to the setting, the Mexican-American border. I asked them how many had read Vargas Llosa, or Paz, or García Márquez in Spanish? How many of them had stepped outside their comfortable linguistic boxes, to seek truth in other worlds and other languages? I mentioned how I had learned German to read Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Mann in the original. Perhaps I was too harsh on my fellow writers. But even in cosmopolitan Manhattan, among the educated, our provincialism is growing. But at what cost, and why?

What happens when a society stops caring about the hard work of imagination, self-criticism, and education? Will it even realize what it has lost? This season, give someone you care about a book in translation, prose or poetry from a university press, or point them to other indie favorites, in magazines or the like. Broaden their minds, and prompt their critical thinking. Help our citizens earn their place in this democracy.

www.ChicoLingo.com

Published on December 15, 2010 06:58

November 9, 2010

The Consumer Used and Abused

Why can't corporations be more flexible? Why can't they put a dollar value on trust, which could be engendered by being more consumer-friendly? Let me tell you about a few different experiences, frustrations, and one triumph in my little island of consumerism. I know the Republicans are currently trumpeting how "the free market" can do everything better than government, how businesses are the solution, not the problem, for reviving the American economy. Let me give you my more complex view.

I love my iPhone. It has truly changed my life, and I owe it to my sons, who converted me to Macs a few years ago. Our family, amazingly, has four iPhones, two MacBooks, a MacBook Pro, and an iMac. We have become avid customers, but only after Aaron and Isaac were able to free me from my PC-Dell hypnosis. You can't see this, but I'm shuddering, remembering the dozens of hours wasted with PC reps trying to solve the stupidest problems.

But today I texted one of my sons, and scolded him for going over his data limit. In about a week, he zoomed past the measly 200 MB of monthly data, the cheapest data plan ($15) offered by AT&T for the iPhone. I'll be paying extra for the over-usage, that is, $15 for the next 200 MB of data. Of course, if I had originally signed up for the next highest data plan, at $25 per month, I would have gotten 2 GB, or ten times the data usage. But then I would be paying $25, instead of $15, per month. The company is basically trying to force you to switch to the higher data plan.

But today I texted one of my sons, and scolded him for going over his data limit. In about a week, he zoomed past the measly 200 MB of monthly data, the cheapest data plan ($15) offered by AT&T for the iPhone. I'll be paying extra for the over-usage, that is, $15 for the next 200 MB of data. Of course, if I had originally signed up for the next highest data plan, at $25 per month, I would have gotten 2 GB, or ten times the data usage. But then I would be paying $25, instead of $15, per month. The company is basically trying to force you to switch to the higher data plan.

Why can't the cheapest data plan be $15 per month for, say, 1 GB? It seems the cheapest plan, at 200 MB, is meant to be exceeded by even the casual data user, so you'll be trapped into paying $15 for every extra 200 MB of over-usage. What a rip! I feel as if I'm being used and abused by AT&T, not a customer, but an easy mark. And I haven't even mentioned the two-year AT&T contract imprisonment I need to endure to use my iPhone.

Again, a credit card I have owned for decades, from a major credit card company that adores the color of money and metals on its plastic, has sneakily changed the amount of time I have to pay my bill every month. From what used to be about 25 days, to now about 8 days! Again, another trap. Forget to pay this credit card for a few days, and they have you by the cojones, so to Sarah-speak.

Is it me, or do you also feel besieged as a consumer? At every turn, instead of service, another trap. Forget to read the fine print, or just act normally, and you will be forking over the fines. I know, some Republican Tea-Partier will say, "Caveat Emptor! The market is king!" But I know many of them feel just as used and abused as I do. I know because I've asked a few of them in private. But in public, at social gatherings where the walls have ears, or web cams, they must repeat their holy mantras.

My question is this: have American consumer businesses become more predatory over time? Is there a way to measure this? If these are not just my experiences, but part of a broader trend, why? Have we somehow lost a social contract with businesses, in which consumers are willing to pay good money for products and services, but also expect these products and services to be reasonable and reliable? Why haven't businesses often put a real value on trust? Because if I trust a business, believe you me, I will go back to it, even it makes an occasional mistake. That's loyalty, and it's worth something.

Let me tell you how my trust was recently restored. Last week, on the black MacBook I use to type this blog, the screen froze as I opened my FireFox browser. The rainbow Apple wheel spun without point or purpose for ten, fifteen minutes. I turned the computer off, and turned it on, but now the dreaded question-mark folder appeared on the screen. No half-bitten white Apple. Nada.

I took my three-and-a-half-year-old MacBook to an Apple store in Manhattan. Apple Genius Nicoya —I will never forget her name— told me my hard drive had failed. Kaput. Dead as plastic. I told her I had AppleCare, but she noted my AppleCare coverage had expired in May, after three years exactly. There's no renewal. That's it. I was screwed. I must have looked puppy-dog-died devastated, not because I lost the info on my drive —I didn't, I had backed up everything— but because I truly loved working on this MacBook. Nicoya stared at me for a moment, then declared, "You know, you never used your AppleCare once, and that's a shame. Why don't I just give you a free hard drive? Can you wait a few minutes while I install it?"

Steve Jobs, Apple Genius extraordinaire, if you ever read this blog, find this Nicoya, and give her a big fat raise and a nice kiss. You know, nothing overtly sexual, but just a thank-you peck. My family and I will be buying Apple products for years because of her. That's what customer loyalty means.

www.ChicoLingo.com

I love my iPhone. It has truly changed my life, and I owe it to my sons, who converted me to Macs a few years ago. Our family, amazingly, has four iPhones, two MacBooks, a MacBook Pro, and an iMac. We have become avid customers, but only after Aaron and Isaac were able to free me from my PC-Dell hypnosis. You can't see this, but I'm shuddering, remembering the dozens of hours wasted with PC reps trying to solve the stupidest problems.

But today I texted one of my sons, and scolded him for going over his data limit. In about a week, he zoomed past the measly 200 MB of monthly data, the cheapest data plan ($15) offered by AT&T for the iPhone. I'll be paying extra for the over-usage, that is, $15 for the next 200 MB of data. Of course, if I had originally signed up for the next highest data plan, at $25 per month, I would have gotten 2 GB, or ten times the data usage. But then I would be paying $25, instead of $15, per month. The company is basically trying to force you to switch to the higher data plan.

But today I texted one of my sons, and scolded him for going over his data limit. In about a week, he zoomed past the measly 200 MB of monthly data, the cheapest data plan ($15) offered by AT&T for the iPhone. I'll be paying extra for the over-usage, that is, $15 for the next 200 MB of data. Of course, if I had originally signed up for the next highest data plan, at $25 per month, I would have gotten 2 GB, or ten times the data usage. But then I would be paying $25, instead of $15, per month. The company is basically trying to force you to switch to the higher data plan.Why can't the cheapest data plan be $15 per month for, say, 1 GB? It seems the cheapest plan, at 200 MB, is meant to be exceeded by even the casual data user, so you'll be trapped into paying $15 for every extra 200 MB of over-usage. What a rip! I feel as if I'm being used and abused by AT&T, not a customer, but an easy mark. And I haven't even mentioned the two-year AT&T contract imprisonment I need to endure to use my iPhone.

Again, a credit card I have owned for decades, from a major credit card company that adores the color of money and metals on its plastic, has sneakily changed the amount of time I have to pay my bill every month. From what used to be about 25 days, to now about 8 days! Again, another trap. Forget to pay this credit card for a few days, and they have you by the cojones, so to Sarah-speak.

Is it me, or do you also feel besieged as a consumer? At every turn, instead of service, another trap. Forget to read the fine print, or just act normally, and you will be forking over the fines. I know, some Republican Tea-Partier will say, "Caveat Emptor! The market is king!" But I know many of them feel just as used and abused as I do. I know because I've asked a few of them in private. But in public, at social gatherings where the walls have ears, or web cams, they must repeat their holy mantras.

My question is this: have American consumer businesses become more predatory over time? Is there a way to measure this? If these are not just my experiences, but part of a broader trend, why? Have we somehow lost a social contract with businesses, in which consumers are willing to pay good money for products and services, but also expect these products and services to be reasonable and reliable? Why haven't businesses often put a real value on trust? Because if I trust a business, believe you me, I will go back to it, even it makes an occasional mistake. That's loyalty, and it's worth something.

Let me tell you how my trust was recently restored. Last week, on the black MacBook I use to type this blog, the screen froze as I opened my FireFox browser. The rainbow Apple wheel spun without point or purpose for ten, fifteen minutes. I turned the computer off, and turned it on, but now the dreaded question-mark folder appeared on the screen. No half-bitten white Apple. Nada.

I took my three-and-a-half-year-old MacBook to an Apple store in Manhattan. Apple Genius Nicoya —I will never forget her name— told me my hard drive had failed. Kaput. Dead as plastic. I told her I had AppleCare, but she noted my AppleCare coverage had expired in May, after three years exactly. There's no renewal. That's it. I was screwed. I must have looked puppy-dog-died devastated, not because I lost the info on my drive —I didn't, I had backed up everything— but because I truly loved working on this MacBook. Nicoya stared at me for a moment, then declared, "You know, you never used your AppleCare once, and that's a shame. Why don't I just give you a free hard drive? Can you wait a few minutes while I install it?"

Steve Jobs, Apple Genius extraordinaire, if you ever read this blog, find this Nicoya, and give her a big fat raise and a nice kiss. You know, nothing overtly sexual, but just a thank-you peck. My family and I will be buying Apple products for years because of her. That's what customer loyalty means.

www.ChicoLingo.com

Published on November 09, 2010 14:00

October 23, 2010

A Peculiar Journey

I go through spurts in writing. This past summer I wrote, and rewrote, more than I have in years. I got into a certain rhythm. The ideas were flowing, and my skills, such as they were, produced work I did not throw away. I experienced what I will only describe as a painful low, yet the summer ended with an unexpected bonanza. Yes, I will have new work next year, but I won't discuss the details until the dust settles.

That's why I stopped writing Chico Lingo three, four times a month. I had to focus on my paid gigs, so to speak, and this blog, which has strangely grown near and dear to my heart, was neglected. Chico Lingo is my way to discuss and explore topical ideas, even philosophical points. It is my way to be part of the cultural and political discourse of this country. It's a community newsletter, an alter ego, a peak into my brain on any given week, and even a platform to jump into a question I want to explore further, perhaps in more crafted writing. I think it's been a good discipline for me to write Chico Lingo.

After the flurry of writing and rewriting of the summer, I have taken a step back from my literary work this autumn. Yes, I am working on shorter pieces. Yes, I am in the middle of a few small projects that editors have asked me for. So the writing work never quite goes away. But the intensity is different, and I am also retooling. I am questioning how I write, from the micro level of the line, to the possible structures of stories, to the architecture of novels in my head. I always try to improve my skills, and I do like to experiment. I hope all of this makes me a better writer.

After the flurry of writing and rewriting of the summer, I have taken a step back from my literary work this autumn. Yes, I am working on shorter pieces. Yes, I am in the middle of a few small projects that editors have asked me for. So the writing work never quite goes away. But the intensity is different, and I am also retooling. I am questioning how I write, from the micro level of the line, to the possible structures of stories, to the architecture of novels in my head. I always try to improve my skills, and I do like to experiment. I hope all of this makes me a better writer.

I work hard, then I take a step back to see if I can find better ways to work. It's a recursive process, Hegelian, if you want to get philosophically fancy, or simply learning by doing, and then thinking about what you learned, and what you did. I imagine myself a maker of a chair, who made lots of chairs —a whole dining room set!— in a concentrated time, and now I take a step back to see how I can learn to make different chairs, with different tools and technologies, with new knowledge about stains, lathes, and woods. I might even try making a table.

One main focus of my retooling is to try capture and use a more poetic rhythm to my prose. To take my written words from not just clear writing and good storytelling, but to sing that song with words that will be my own.

It has been a long literary trek for me. Early on I think I wrote in a certain simple way because my native language was not English, but Spanish, or more precisely the Spanglish of El Paso. Years ago I was simply trying to get my point across. I was trying to survive, whether it was at Ysleta High, or Harvard and Yale. Also, I believed first and foremost in ideas, not words. Perhaps this is the curse of the philosophical mind, to know that what you write —its logic, argument, and import— is far more essential than how you write it. I still believe this is true, in a way. Heidegger, for example, was a terrible writer, but a great thinker. What he wrote, once you more or less understood it, reoriented what the world could be. Nietzsche was that great exception as a philosopher, a unique and important thinker for what he wrote, but also a gifted stylist by how he wrote in German.

So I needed to write simply, to get my point of across, to be heard. I loved thinking about complex philosophical problems, and so that also lent itself to writing simply and directly. When you read philosophical papers, the writing is often direct and relatively simple, but your head hurts trying to understand the argument and logic.

But the reason I left philosophy was because I found it too isolating. I married philosophy with literature in my stories, to try to achieve this nexus of exploring difficult questions, but through stories, believable characters, many of them from the Mexican-American border. Writing philosophy in literature was also a way to destroy stereotypes in Mexican-American literature. Over decades of writing, I became better at it. My English improved. I became more of a native English speaker, even though I never left my Spanish behind. After much struggle and self-education and self-reinvention, I again wanted more of myself and my writing.

That's at the point I am now. Where I want more from my work in English. More poetry. More language that cuts through the colloquial and the cliché. Whereas early on in my writing career, I hardly read any poetry without being baffled or bored. Now I am primarily reading poetry, and lustily so. I gave a speech recently, which delved into my peculiar journey, "From Literacy to Literature." I hope you get the idea. I still remember how Plato ridiculed the poets and warned against their influence, but now I happily inhabit that world in a poem, and it is that momentary beauty that nourishes me even as I try to take it apart.

www.ChicoLingo.com

That's why I stopped writing Chico Lingo three, four times a month. I had to focus on my paid gigs, so to speak, and this blog, which has strangely grown near and dear to my heart, was neglected. Chico Lingo is my way to discuss and explore topical ideas, even philosophical points. It is my way to be part of the cultural and political discourse of this country. It's a community newsletter, an alter ego, a peak into my brain on any given week, and even a platform to jump into a question I want to explore further, perhaps in more crafted writing. I think it's been a good discipline for me to write Chico Lingo.

After the flurry of writing and rewriting of the summer, I have taken a step back from my literary work this autumn. Yes, I am working on shorter pieces. Yes, I am in the middle of a few small projects that editors have asked me for. So the writing work never quite goes away. But the intensity is different, and I am also retooling. I am questioning how I write, from the micro level of the line, to the possible structures of stories, to the architecture of novels in my head. I always try to improve my skills, and I do like to experiment. I hope all of this makes me a better writer.

After the flurry of writing and rewriting of the summer, I have taken a step back from my literary work this autumn. Yes, I am working on shorter pieces. Yes, I am in the middle of a few small projects that editors have asked me for. So the writing work never quite goes away. But the intensity is different, and I am also retooling. I am questioning how I write, from the micro level of the line, to the possible structures of stories, to the architecture of novels in my head. I always try to improve my skills, and I do like to experiment. I hope all of this makes me a better writer.I work hard, then I take a step back to see if I can find better ways to work. It's a recursive process, Hegelian, if you want to get philosophically fancy, or simply learning by doing, and then thinking about what you learned, and what you did. I imagine myself a maker of a chair, who made lots of chairs —a whole dining room set!— in a concentrated time, and now I take a step back to see how I can learn to make different chairs, with different tools and technologies, with new knowledge about stains, lathes, and woods. I might even try making a table.

One main focus of my retooling is to try capture and use a more poetic rhythm to my prose. To take my written words from not just clear writing and good storytelling, but to sing that song with words that will be my own.

It has been a long literary trek for me. Early on I think I wrote in a certain simple way because my native language was not English, but Spanish, or more precisely the Spanglish of El Paso. Years ago I was simply trying to get my point across. I was trying to survive, whether it was at Ysleta High, or Harvard and Yale. Also, I believed first and foremost in ideas, not words. Perhaps this is the curse of the philosophical mind, to know that what you write —its logic, argument, and import— is far more essential than how you write it. I still believe this is true, in a way. Heidegger, for example, was a terrible writer, but a great thinker. What he wrote, once you more or less understood it, reoriented what the world could be. Nietzsche was that great exception as a philosopher, a unique and important thinker for what he wrote, but also a gifted stylist by how he wrote in German.

So I needed to write simply, to get my point of across, to be heard. I loved thinking about complex philosophical problems, and so that also lent itself to writing simply and directly. When you read philosophical papers, the writing is often direct and relatively simple, but your head hurts trying to understand the argument and logic.

But the reason I left philosophy was because I found it too isolating. I married philosophy with literature in my stories, to try to achieve this nexus of exploring difficult questions, but through stories, believable characters, many of them from the Mexican-American border. Writing philosophy in literature was also a way to destroy stereotypes in Mexican-American literature. Over decades of writing, I became better at it. My English improved. I became more of a native English speaker, even though I never left my Spanish behind. After much struggle and self-education and self-reinvention, I again wanted more of myself and my writing.

That's at the point I am now. Where I want more from my work in English. More poetry. More language that cuts through the colloquial and the cliché. Whereas early on in my writing career, I hardly read any poetry without being baffled or bored. Now I am primarily reading poetry, and lustily so. I gave a speech recently, which delved into my peculiar journey, "From Literacy to Literature." I hope you get the idea. I still remember how Plato ridiculed the poets and warned against their influence, but now I happily inhabit that world in a poem, and it is that momentary beauty that nourishes me even as I try to take it apart.

www.ChicoLingo.com

Published on October 23, 2010 06:17

September 11, 2010

Terror and Humanity

(On September 11, 2001, an editor from Newsday called me at home and asked me to write about what was happening in New York. I didn't know what to write, or if I could write anything. I was traumatized by what I saw on TV and what was happening a few miles from my apartment. The next day the following article appeared in Newsday and many other newspapers. I think the words still resonate today, amid the battles we are fighting with each other and within ourselves.)

This one is for the tho...

This one is for the tho...

Published on September 11, 2010 20:58

August 26, 2010

American Anima

Sometimes you need a break to regain your anima. That is what I needed after finishing a few projects, after a long hot summer, after trying to make sense of the American political scene where a large segment of the population lives in willful ignorance or willful opposition to the great values I thought this country stood for.

Yesterday I suggested to my thirteen-year-old son Isaac that he read George Orwell's 1984 : freedom is slavery, Barack Obama is a Muslim, bigotry is tolerance. Does the...

Yesterday I suggested to my thirteen-year-old son Isaac that he read George Orwell's 1984 : freedom is slavery, Barack Obama is a Muslim, bigotry is tolerance. Does the...

Published on August 26, 2010 17:24

Chico Lingo, by Sergio Troncoso

Sergio Troncoso is the author of A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant's Son, The Last Tortilla and Other Stories, Crossing Borders: Personal Essays, and the novels The Nature of Truth and From This Wicked Pat

Sergio Troncoso is the author of A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant's Son, The Last Tortilla and Other Stories, Crossing Borders: Personal Essays, and the novels The Nature of Truth and From This Wicked Patch of Dust. For many years, he has taught at the Yale Writers' Workshop in New Haven, Connecticut.

...more

- Sergio Troncoso's profile

- 111 followers