Susan Maxwell's Blog, page 4

January 12, 2024

Five For Friday #16

It's already the second Friday of 2024—is the year running away out of control? Anyway, it's Friday, the day on which I will always try to post on this blog. In an ideal world (or if I were an ideal author), I would be posting exquisite, accomplished pieces of writing on a practically daily basis, but we're not quite there yet.

I am taking a different approach to the Five For Friday posts this year: instead of focusing on five connected things, I will mention five disparate items I have come across in the course of the week and that have piqued my interest or resonated with me in some way. A more serendipitous approach, and one that will be more cognisant of the gems crafted by other, more expert, toilers in the ateliers of the floating online world.

So here goes…

1. Things HeardA Weird Studies podcast on Algernon Blackwood's short story 'The Wendigo'As with all masters of the genre, Blackwood's take on the weird is singular: here, it isn't the cold reaches of outer space that elicit in us a nihilistic frisson, but the vast expanses of our own planet's wild places -- especially the northern woods. In his story "The Wendigo," Blackwood combines the beliefs of the Indigenous peoples of the Eastern Woodlands with the folktales of his native Britain to weave an ensorcelling story that perfectly captures the mood of the Canadian wilderness. In this conversation, JF and Phil discuss their own experience of that wilderness growing up in Ontario. The deeper they go, the spookier things get.

This episode recalled to mind Ann Tracy's 1980 novel Winter Hunger, which I had read many years ago.

2. Things SeenTwo episodes of The Avengers .Somehow, though knowledge of this iconic slice of TV history had managed to penetrate even the isolated fortress of my thought-world, I had never actually watched any of it. My editor, fresh from a trip to the lurid delights of the Big City, proceeded to remedy this sad state of affairs via a set from the 1965 series picked up in a DVD exchange shop.

Daft, but ineffably stylish (the Avengers, that is, not the editor).

3. Things ReadTrying to find a Corridor of Mirrors, a post by Mark Valentine, on the excellent Wormwoodiana blog, about a strange and elusive book by its equally elusive author, Chris Massie.But where have all those copies of Corridor of Mirrors gone? Sometimes I entertain the thought that an obsessive collector has amassed them in his library lined with looking-glasses, so that nobody else can possess the book but he, and he can see them all, multiplied to infinity, as he stalks up and down in his scarlet smoking hat and velvet coat, and gloats.

I now have to twitch every so often in an attempt to shrug off the urge to embark myself on an obsessive search for this almost-lost work.

4. Things RecalledFor some reason, my mind strayed to the recollection of a sculpture I had seen years ago in the Hugh Lane Gallery. It was a work in stainless steel by Eilis O'Connell, a piece titled From a Place no Longer Imagined. Although not a figurative work, I would hesitate to call it abstract, so resonant was it with things tantalisingly just out of reach, enigmatic yet eloquent in its otherness, an artefact from a realm alien to but contiguous with our own. I don't know if it is among the current exhibits: I didn't see it the last time I was in the gallery. But I always look for it. .gr_grid_container { /* customize grid container div here. eg: width: 500px; */ } .gr_grid_book_container { /* customize book cover container div here */ float: left; width: 98px; height: 160px; padding: 0px 0px; overflow: hidden; } 5. Books I'm reading for pleasure or research

I don't know if it is among the current exhibits: I didn't see it the last time I was in the gallery. But I always look for it. .gr_grid_container { /* customize grid container div here. eg: width: 500px; */ } .gr_grid_book_container { /* customize book cover container div here */ float: left; width: 98px; height: 160px; padding: 0px 0px; overflow: hidden; } 5. Books I'm reading for pleasure or research

My Goodreads page »

Share book reviews and ratings with Susan, and even join a book club on Goodreads.

January 7, 2024

Happy New Year! And What the Book Fairy Brought...

First things first—we wish you all a happy New Year, and hope that 2024 brings only good and pleasant things your way.

Here at the Bibliothèque, we're reluctantly emerging from eating and sleeping mode and dragging unwilling feet back to the world of tasks, deadlines and all the rest of it. Many of these tasks and deadlines have, alas, little to do with writing: I find myself grumpily complaining, along with Larkin, "Why should I let the toad work / Squat on my life?" (I can almost hear the myriad retorts of "pity about you!")

Anyway, at least some of the festive comfort of the season will acccompany me into the year: we had Christmas and a birthday, so several lovely book-presents made their way onto the household shelves. Some for fun, some for more serious reading, all most welcome.

Cocker, Mark (2023) One Midsummer’s Day: Swifts and the Story of Life on Earth. London: Jonathan Cape.

Gombrowicz, Witold (1939 [2023]) The Possessed. Translated by A. Lloyd-Jones. London: Fitzcarraldo Editions.

Haynes, Natalie (2023) Divine Might: Goddesses in Greek Myth. London: Picador.

Pardoe, Rosemary A. (2018) The Black Pilgrimage & Other Explorations: Essays on Supernatural Fiction. Birmingham: Shadow Publishing.

Vincent, Bruno (2020) Five go Absolutely Nowhere. London: Quercus (Enid Blyton for Grown-Ups).

Vincent, Bruno (2017) Five Lose Dad in the Garden Centre. London: Quercus (Enid Blyton for Grown-Ups).

Williamson, Colm (2023) Waterford Whispers News 2023. Dublin: Gill Books.

Bibliothèque des Refusés is the imprint of independent author and scholar Susan Maxwell.

October 20, 2023

Five For Friday #15: Sl-o-o-w Writing

Eagle-eyed readers may have noticed that my current WIP, A Wild Goose Hunt, has been 'coming soon' since at least May. Hopefully, it is now in its final editorial and production stages, but the experience suggested this week's theme—books that took a long time to write. In the light of these examples, my own dilatoriness seems a mere drop in the ocean…

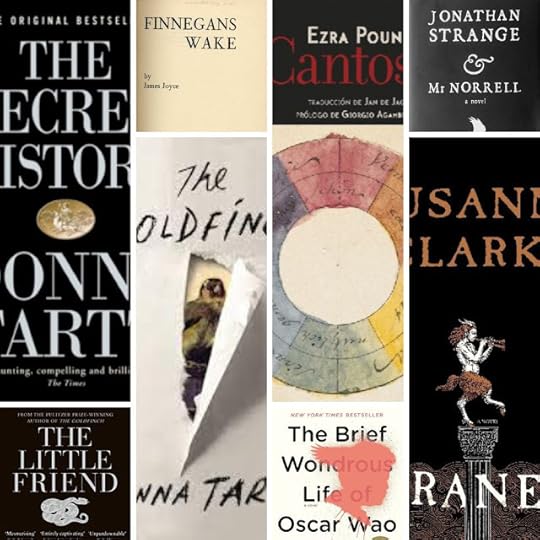

1. Donna Tartt takes a mere decade to write her novels; ten years between The Secret History and The Little Friend, and the same again before The Goldfinch made its appearance.

2. Junot Díaz's The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao also took ten years, during which time the author apparently almost gave up on completing a novel that then won, among other accolades, the Pulitzer Prize.

3. James Joyce took sevennteen years to write Finnegans Wake; he is said to have predicted that it would take most people the same length of time to read it.*

4. Susanna Clarke apparently began Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell in 1993, and a full twenty years later, it was finished, and picked up by Bloomsbury. Fans of Clarke had to wait another sixteen years for the exquisite Piranesi.

5. Ezra Pound’s The Cantos, controversial as it was, took fifty-seven years and still was not complete when the poet died. Now there's something to which I can aspire!

*I don’t think that the Backlisted podcast has tackled Finnegans Wake, but in one episode one of the presenters had just read it and commented on how it is (as Beckett said) not meant to be read; and that perhaps it is meant to be read aloud or sung, and how it is very funny.

WEBSITE www.biblioref.com

FOLLOWSign up to the Newsletter for extra updates and offersMastodon Bluesky Twitter LibraryThing Goodreads Facebook Instagram YouTube

BUY the BOOKSHollowmen Fluctuation in Disorder And the Wildness A Wild Goose Hunt Good Red HerringIndividual short stories

Bibliothèque des Refusés is the imprint of independent author and scholar Susan Maxwell.

October 17, 2023

Short Stories: 2. Battle Book

Battle BookThe depths of winter. Clement and Bosco are underage volunteers in the Resistance, fighting an alien invasion. Bosco is given charge of the 'battle book', a manuscript believed to have protective powers. The youngsters accidentally initiate engagement and a fragile ad hoc cessation of hostilities when they stumble into one of the aliens' encampments. A side-story to the Hibernia Altera sequence, set some centuries before the novels.

'Battle Book' is aligned to the Hibernia Altera world associated with my Muinbeo and Flux Avellana novels. Like most of the stories in this world, Battle Book is a straightforward fantasy adventure story. It presents an encounter between humans and aliens during the First Alien Invasion, which took place some centuries before the action of the novels.

Cumdach is an Old Irish word meaning a cover, or shrine, for a book (the modern Irish word cumhdach means more generally a protective covering). The idea of a manuscript having talismanic status is not new at all. It is thought that the Book of Kells, when taken out for use on high days and holidays, was not touched by bare hands, but handled through a cloth, probably purple. An archivist working in Trinity College Dublin (where the Book of Kells is kept) told me that once when the manuscript was being escorted downstairs into the storage area, one of the security guards very quickly touched the edge of the book, and then blessed themselves.

The Psalter of St. Columba is better known as the Cathach, the ‘battler’, because when it came into the possession of the O’Donnells of Donegal, they carried it deosil—sunwise—around their army before battle. In the story, Bosco has thrust upon him the job of carrying the battle-book, and when he and his friend Clement lose their way in the dark, the action that was supposed to protect the Earl’s army from the alien enemy is the action that brings the two face-to-face.

'Battle Book' involves a manuscript and a character whose afterlife play an important rôle in my forthcoming novel A Wild Goose Hunt, the second book of the Muinbeo Chronicles.

https://books2read.com/BattleBook

https://books2read.com/BattleBook

https://books2read.com/fid

https://books2read.com/fidOctober 13, 2023

Five For Friday 13th: Scary Stories

Well, it’s Friday 13th, what else could be the subject of Five For Fridays, apart from Five Scary Stories? I have always had a fondness for ghost-stories and weird tales, and since it would be difficult to select the five scariest, I’ll just do random ones that I like.

One Christmas, when I was 12 or 13, and spending Christmas in bed with some ailment or another, one of my siblings gave me a copy of Enthralling Mystery Stories, which had several really good ones included, four of which are below. The fifth is a narrative poem from one of the first books I ever bought myself, Hist Whist. So we’re not exactly in visceral horror territory, but they were certainly all scary enough when I first set eyes on them, and 'Lost Hearts' in particular is the sort of tale that is best read in broad daylight, even by grown-ups.

(Speaking of M.R. James, if you sign up to my newsletter you get a free e-book of my short story ‘Veni, vidi, vicit’, written in homage to the master and exclusive to subscribers…)

M.R. James (1862–1936) 'Lost Hearts'

It is always a bit of a toss-up for me between 'Lost Hearts' and 'Oh Whistle and I’ll Come To You, My Lad' as the scariest of James’ stories. 'Lost Hearts' has the added attraction of being the first M.R. James story I ever read.

An orphan boy, Stephen, is unexpectedly taken into the home of his adult cousin in Lincolnshire, and has a series of strange experiences that are too realistic to be dreams. His cousin, it seems, has previously been hospitable to two other children, who may or may not have resembled the figures Stephen sees in the garden. It is not an unfamiliar narrative for James, featuring as it does the over-focused academic who in searching for knowledge is becoming reckless. The source of the threat, on the other hand, is not James’ more usual formless and repellent monsters, but rather recognizable figures that, deformed and ‘othered’ by their experience, are ultimately sympathetic.

Hugh Walpole (1884–1941) 'Tarnhelm'

If any story could give James a run for his money as a quintessential ghost story, it is arguably 'Tarnhelm'. There is the lonely, isolated child, sent to spend school holidays with various reluctant relatives, eventually landing up in the "naked, unsympathetic hills" of the North of England. There is his odd and nefarious uncle Robert, Robert’s kind but timid brother Constance; there are bad dreams, an imposing, ugly house, a strangely powerful skullcap, and a faint, mysterious smell of caraway. It is an intensely and effectively atmospheric tale with a touching homosocial element.

W.W. Jacobs (1863–1943) 'The Monkey’s Paw'

A couple and their beloved son come into possession of a dried monkey’s paw that is said to give three wishes. Disaster awaits those who do not remember that the givers of wishes of this sort are notoriously mischievous in their interpretations of anything but the most carefully worded of demands. Like many of M.R. James’ stories, part of the effect of Jacobs’ story lies in the catastrophic disruption of a very recognisably comfortable, even modest, life, and in the sense of advancing horror warning them that, in coming to regret their light-hearted wish, they have brought something worse in a "fusillade of knocks" to the door of their home.

Charles Dickens (1812–1870) 'The Signalman'

I am not particularly a fan of Dickens, but this is a genuinely chilling tale, economically told.

The narrator meets the signalman at a railway station, who is tormented by ghostly appearances that not only seem very convincing, but have always predicted a disaster. He has recently seen the apparition again, and is fraught with fear as to what is in store. The story is a curious mix of the claustrophobic and expansive; much of the narration takes place in the very small stationhouse, but there is movement in space along the long stretch of the tunnel in which previous tragedies have taken place, and in time as the signalman reflects on his youth, his squandered academic opportunities, and waits to see what future event the haunting figure is predicting.

Stevie Smith (1902 – 1971) 'Little Boy Lost'

Stevie Smith’s account of the child who followed the beckoning witch is quite low-key in some ways (“Did I love father, mother, home? / Not very much; but now they’re gone / I think of them with kindly toleration”) but pitiless. The straying from the path seemed like so inconsequential an act to have brought such doom upon the narrator; there is a strong sense of this being the voice from the last throes.

The illustrations in my copy of Hist Whist (1975) fascinated me; they’re really very creepy (they are by Kathy Wyatt), and I copied them many times to try to learn their weird secrets.

WEBSITE www.biblioref.com

FOLLOWSign up to the Newsletter for extra updates and offersMastodon Bluesky Twitter LibraryThing Goodreads Facebook Instagram YouTube

BUY the BOOKSHollowmen Fluctuation in Disorder And the Wildness A Wild Goose Hunt Good Red HerringIndividual short stories

Bibliothèque des Refusés is the imprint of independent author and scholar Susan Maxwell.

October 10, 2023

Short Stories: 1. Someone Had Been Telling Lies

Someone Had Been Telling LiesJae receives a summons to the office—does this mean a place on the inside track in an organization where position is everything? Slipstream fiction set in the 'bureaucratic gothic' universe of the novel Hollowmen.

'Someone Had Been Telling Lies' (the name comes from the first line of Kafka’s The Trial) is associated with a fictional world, that of the novel Hollowmen. It, too, is a sort of testing-out of ideas, of aesthetic, and of ambiance. The action takes place in the Institute, unnamed in the story, and concerns the initiatory moves in the Processs that starts against Kaye in Hollowmen.

The world the characters understand to be the ‘real’ world has no anchor in, or even ability to see, the ‘real’ worlds around them: the dead dog, the users of wheelchairs, even their colleague Kaye. The characters are protected from consensus reality by their participation in the world of the Institute. The material wealth the Institute provides makes a world of difference to its workers, for whom all other workers are ‘other’, barely human when seen skating on the river. With life in the Institute comes an insulating sense of entitlement, and they register neither that everyday world nor the co-existing world of the "dark and speckled flicker," the sucker-marks on the window, or the blood on the snow.

At the same time, Jae, Kaye, and Elle’s own world is floating and transient in its operations. Jae struggles to comprehend the material world into which they wake, surrounded by signs that temporarily make no sense, until "the darkness tilts" and comprehension returns. Jae is constantly on the uneasy edge of comprehension, aware of the ceaseless competitive horse-trading of information within the Institute, but timid about participation. It is unclear who has any real understanding of what is going on. By the end, Jae still has no idea what has ‘really’ happened, but can revel in it having been a good day because of the success of the last exchange with Elle: Jae has found the knack of presentation, of disruption with meaninglessness, of wielding "inspired nullity."

https://books2read.com/SHBTL

https://books2read.com/SHBTL

https://books2read.com/fid

https://books2read.com/fidOctober 6, 2023

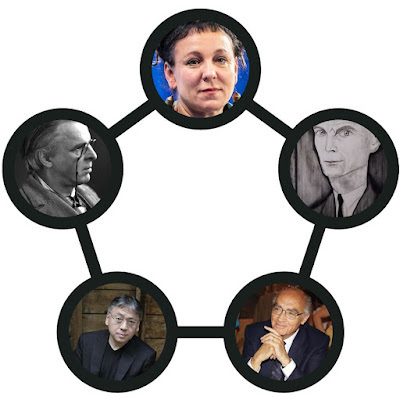

Five For Friday #13: Nobel Prize Winners

2018: Olga TokarczukTokarczuk was awarded the prize "for a narrative imagination that with encyclopedic passion represents the crossing of boundaries as a form of life." I was introduced to her work through the 2009 novel Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, and immediately had to erect a plinth in my private literary pantheon to honour a new deity.

2017: Kazuo IshiguroIshiguro, "who, in novels of great emotional force, has uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world," is probably most widely known for The Remains of the Day. His When We Were Orphans is, like Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow… is in the form of a mystery story, which always doubly endears me to a work of literature.

1998: José SaramagoI’ve mentioned Saramago before in a blog post: my tastes intersect at several points with the work of this author "who with parables sustained by imagination, compassion and irony continually enables us once again to apprehend an elusory reality." An element of the fantastic, a degree of experimentalism in the writing, and the archival setting of All the Names are the sorts of things to which I am most receptive.

1969: Samuel BeckettBeckett was awarded his prize "for his writing, which – in new forms for the novel and drama – in the destitution of modern man acquires its elevation." Along with James Joyce and Flann O’Brien (Brian O’Nolan), he is one of the towering triumvirate of Irish modernist literature. He lived in Paris for most of his adult life, and wrote many of his works, including Waiting for Godot, in French.

1923: W.B. YeatsIn the year after Ireland gained independence, Yeats was awarded the prize "for his always inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation." One of the most widely known English-language poets of the 20th Century, he was also a prominent esotericist. But even someone so attuned to the otherworldly might not have foreseen that one of his most esoterically informed poems, The Second Coming, would be quoted by beings and in worlds far beyond our earthly realm…

September 22, 2023

Five For Friday #12: Discovering Irish Children's Literature 2

Last week's FFF featured five contemporary Irish children's authors, all of them traditionally published. This week, it's the indies' turn, and I am highlighting five Irish independent authors of children's and young adult books. All of this is to tie in with the excellent campaign currently being run by Discover Irish Children's Books.

1. Chris Spence

Chris’s Rock Happy is the first in a near(ish)-future trilogy of dystopian thrillers. The adventures kick off fifteen years after a shock disruption of a presidential election in the United States. Alex is accustomed to his MeChip providing him with entertainment, not making him see things others don’t see. There are implants, ‘Fixers’, a mysterious old man, and unexpected enemies, and the school’s battle-of-the-bands to contend with. Books 2 and 3 are due for release next month. Chris also writes non-fiction on environmental matters.

2. Eliza Green

Eliza writes science fiction for adults and young adults. Her YA Resistance Files series starts with newly-orphaned Anya’s placement in a training facility, where she is pitted against fellow-trainees, and where eventually the facility's sinister motives are revealed. Over the course of the series, she is trapped in the Collective, takes refuge with rebels, and eventually has the opportunity for a fresh start. There are eight Resistance Files books. Eliza also writes paranormal romance as Kate Gellar.

Pat, who scarcely needs introduction, has written prose, plays and poetry for younger readers as well as for a general audience, and has hosted television shows for children. Until 2015, he sold his poetry directly to readers in and around Westmoreland Street, College Green, and (as far as I recall) Grafton Street. He is still involved in the Dublin arts scene (although apparently, some of his books claim to be protected by the ‘Bratislava Accord’, meaning that his work is not to be included in, among other things “anything with the word ‘Arts’ in it.”) Though some of his poetry was published by traditional publishers, since the 1990s, he has self-published his work through Willow Publications.

Valinora Troy is a children’s fantasy author. Her Lucky Diamond trilogy (ages 8–12) is the story of five orphans and their adventures in Nivram, a country in the guardianship of the King of Diamonds and his family. They rescue the princess, face down the vengeful Queen Rose, and discover the last remnants of evil in the Nivram’s Great Forest. Aside from writing, Valinora regularly reviews books and writes newsletters; she was a panellist for the Cybils Awards in 2021, ably supported by a hard-working spaniel.

5. Me (you weren't expecting modesty, were you?)

Though Good Red Herring was traditionally published (thank you, Little Island!), the second book in the Muinbeo Chronicles—which is called A Wild Goose Hunt and is with the editor as we speak!—will be indie-published by my imprint Bibliotheque des Refusés. The very same BdR published And the Wildness, the first of the Flux Avellana series, set before the Muinbeo Chronicles start, but intersecting with it later. It will also publish a collection of four Flux Avellana companion stories (or I will want to know the reason why), which is my WIP, and called Storm Watchers. I also write for adults, or at least those who like irreal, speculative, and sometimes experimental literature.

WEBSITE www.biblioref.com

FOLLOWSign up to the Newsletter for extra updates and offersMastodon Twitter LibraryThing Goodreads Facebook Instagram YouTube

BUY the BOOKSHollowmen Fluctuation in Disorder And the Wildness A Wild Goose Hunt Good Red HerringIndividual short stories

Bibliothèque des Refusés is the imprint of independent author and scholar Susan Maxwell.

September 17, 2023

Short Stories: Introducing a standalone series

Earlier this year, I published a short story collection, Fluctuation in Disorder, which is available in both print and e-book versions. The stories reflect both changes in my approach to writing over time (they span a period of approximately 20 years) and some of the range of genres and styles in which I write. I am very happy with this in one way, but it does make it hard to market in the focused way all the helpful advice for independent authors stipulates: not everyone who likes fairly conventional fantasy will find literary experimentation to their taste, and vice versa. Someone might be intrigued by the language or premise of one story while feeling the rest really aren't their cup of tea, and thus not unnaturally feel that buying the whole book would be a bit of a risk.

Mulling over this conundrum, I suddenly remembered that, as an indie author, these are my stories, published under my imprint, and that basically I can do whatever I like with them—this is the good part of the indie vs traditional publishing trade-off. So I decided to publish all of the collected stories individually, as standalone (very short) e-books. Think of it as a selection box where you can take all the nice sweets while leaving the rest in the box, and all without any feeling of guilt! This approach has the added benefit of allowing me to publish uncollected stories as I write them (or dig them out of some lost corner of my notebooks or laptop).

You can have a look at the available short stories here; over the coming week or so I will be posting about each individually.

WEBSITE www.biblioref.com

FOLLOWSign up to the Newsletter for extra updates and offersMastodon Twitter LibraryThing Goodreads Facebook Instagram YouTube

BUY the BOOKSHollowmen Fluctuation in Disorder And the Wildness A Wild Goose Hunt Good Red Herring

Bibliothèque des Refusés is the imprint of independent author and scholar Susan Maxwell.

September 15, 2023

Five For Friday #11: Discovering Irish Children's Literature 1

Today, I would like to highlight a campaign to promote Irish children's literature, which has been running since the beginning of the month under the aegis of Discover Irish Children's Books. The campaign was created by author Sarah Webb in response to the extraordinary fact that Irish writers of children’s books rarely got a mention on lists of children’s top-ten bestsellers in Ireland. What better choice than five authors from this wealth of talent? Four of whom I have actually met in real life, despite being a misanthropic grouch?

1. Claire Hennessy, “writer, tea-drinker”

Dublin-based Claire not only writes YA fiction, but helps others do so, too. Claire’s first novel was Dear Diary, and possibly her best known is Nothing Tastes as Good. She also writes poetry, and reviews children’s and young adult literature for the Irish Times.

Dublin-based Claire not only writes YA fiction, but helps others do so, too. Claire’s first novel was Dear Diary, and possibly her best known is Nothing Tastes as Good. She also writes poetry, and reviews children’s and young adult literature for the Irish Times.

Eve is also an artist, provider of crafting and writing workshops, and poster of lovely videos of birds, squirrels, and hagstones, many from around her home on a hill in Wexford.

3. Olivia Hope

In 2022, Bloomsbury published Olivia’s beautiful picture-book, Be Wild, Little One, to great acclaim—no less a children’s literature great than Shirley Hughes called it ‘magical’, and Michael Morpurgo chose it as one of his five favourite books for children.

She also researched and wrote a re-telling of the story of Samhain, as part of Siamsa Tire’s Associate Artist Scheme, involving a púca and a chorus of banshees (I mean, what is not to love with that combination?). She worked with 20 other artists, resulting in an exhibition (held in the museum of her home county of Kerry) called Slí Abhaile/A Way Home.

Olivia is a former record-breaking hammer-thrower and often tweets about cheese.

Nigel Quinlan has written two books (well, probably more, but two are published), one The Maloneys' Magical Weatherbox and The Cloak of Feathers (Hachette Children’s). Both fantasy, one involving a family whose father helps to control the weather by turning the seasons (except when it doesn't work) and the other involving a ‘fairy festival’ at which, once a century, the Gentle Folk actually turn up. They’re not really all that Gentle, either…

He also wrote an article about editing that will have other authors both nodding and flinching in recognition: “This was less like writing, and more like Austerity”, as he chopped favoured chunks out of The Cloak of Feathers to polish a very good novel out of the bigger one he had written. Happily, the banshees on bicycles stayed.His local bookshop is also mine: the very excellent Sheelagh-na-Gig in Cloughjordan.

One of the most formidable and respected presences in Irish children’s literature, Siobhán has won many awards for her numerous books for children, written in both English and Irish. She has also translated books (from German).

In 2011, discontent with the opportunities for Irish authors of good children’s literature, she founded and became the commissioning editor and publisher in Little Island Books, a New Island Books imprint that focused on that very demographic. Little Island has published many excellent books—Patricia Forde’s Wordsmith, Sam Thompson’s Wolfstongue and Fox’s Tower, and… ahem… Good Red Herring.

Siobhán has seen children’s literature from a great many angles: writing it, teaching about it; she was Ireland’s first Laureate na nÓg/Children’s Laureate, and is a former editor for both Inis (the magazine of Children’s Books Ireland) and Bookbird (the journal of the international children’s literature organization, IBBY).

WEBSITE www.biblioref.com

FOLLOWSign up to the Newsletter for extra updates and offersMastodon Twitter LibraryThing Goodreads Facebook Instagram YouTube

BUY the BOOKSHollowmen Fluctuation in Disorder And the Wildness A Wild Goose Hunt Good Red Herring

Bibliothèque des Refusés is the imprint of independent author and scholar Susan Maxwell.