Robert E. Wright's Blog, page 10

April 25, 2015

The Other Two Dakotas Speech 4/25/2015 Center for Western Studies Dakota Conference Luncheon Keynote

Little Business on the Prairie: Entrepreneurship in South Dakota, 10,000 BC to Present or, the Other Two DakotasBy Robert E. Wright, Nef Family Chair of Political Economy, Augustana College SD

Even school kids know that there are two Dakotas -- North and South – but a surprising number of adults who live outside of the upper Midwest readily conflate the two. North Dakota, not South Dakota, is the emerging energy giant. According to the Minneapolis Fed, which reigns over both states as well as Montana, Minnesota, and parts of Wisconsin and Michigan, South Dakota receives no direct benefit from the Bakken formation’s energy riches, a fact that no South Dakotan had to learn from a bean counter in the Twin Cities. Most of South Dakota’s population resides in the south and east part of the state, far from the energy action in northwestern North Dakota. South Dakota’s largest city, Sioux Falls, is 656 miles from boomtown Williston, North Dakota by interstate highway. That is slightly longer than the distance between Boston, Massachusetts and Cleveland, Ohio. South Dakota’s second largest city, Rapid City, is 333 miles from Williston, a five and a half hour drive on non-Interstate roads, or the equivalent of driving from Washington, DC to Cleveland on back roads. South Dakota does possess ample energy resources but they are all renewable -- hydro, solar, and wind – and the latter two are almost completely undeveloped. It also has a little low grade lignite but that stuff has never found anything but a local market, and a desultory one at that.I make this point immediately so that nobody in the audience remains under the misapprehension that South Dakota’s economic prosperity is in any way built on fossil fuels. South currently lags North: at the end of February, South Dakota’s unemployment rate was 3.4 percent compared to North Dakota’s 2.9 percent, which was second in the nation behind Nebraska, and North Dakota’s $55,000 per capita income in 2012 was third in the nation and well ahead of South Dakota’s $43,000 per head. But South Dakota is no laggard as its unemployment rate is third best in the nation and its per capita income is 20th and a few hundred dollars above the national average. Moreover, North Dakota’s economy faces much greater risks than does South Dakota’s. You may have noticed that energy prices are way down; North Dakotans certainly have as the price of North Dakota sweet crude recently dropped below $50 a barrel and half the state’s rigs shut down. South Dakotans, by contrast, love cheap oil. South of the quartzite border separating North from South, another “two Dakotas” loom large, the East and West River sections of South Dakota. Few doubt the importance of the distinction, though some think the James River superior to the Missouri River as the actual dividing line between the two sections. The James, or Big Jim as some affectionately call it, flows well east of the Missouri River until the big river turns east to meet it near Yankton. Like the Missouri River Valley, the 50 to 75 mile wide James River Valley bisects the state but it is perhaps best seen as a transition zone. To its east, agriculturalists expect adequate precipitation and usually get it. To its west, agriculturalists don’t expect enough rain and typically are not disappointed. In the Big Jim Valley proper, nobody knows what to expect. One year can be dry as a bone and the next farmers wish that they had planted catfish instead of corn as their fields flood. During flood years, crossing the James is quite a harrowing experience but during droughts the river becomes little more than a 710 mile long “crick.” That is why the Big Mo, the Big Muddy, the now tamed Missouri River, is probably the best dividing line between East and West.Wherever one draws the line, West River is more about ranching than farming, mule deer and turkeys than whitetails and pheasants, cowboys and rodeos than dairymaids and county fairs. West River is home to the Badlands, vast Indian Reservations, Mount Rushmore and the Black Hills, the Sturgis motorcycle rally, and the Passion Play. Libertarians roam as freely West River as liberals do in downtown Sioux Falls and the hallways of East River state universities. One could go on and on about the differences between the two sections as many South Dakotans do, ignorant, perhaps, of what Sigmund Freud called the narcissism of minor differences. Outsiders can no more easily distinguish between an East River Dakotan and a West River Dakotan than the median American can tell the difference between a Swede and a forest Finn, a Fleming and a Walloon, or a Hmong and a Karen. Partly that’s because so many South Dakotans, whether they hail from east or west of the Mighty Mo’, make their living the same way, via entrepreneurship.If that sounds incredible to you, do bear in mind several facts. First, the vast majority of entrepreneurs are not rich and famous like Steve Jobs, Elon Musk, or Thomas Edison. Most entrepreneurs are merely replicative. In other words, they extend an existing product to a new market so the economic rents, by which I mean above average profits, they earn tend to be small and/or fleeting. Most farmers and ranchers are replicative entrepreneurs, as are most retailers and other small business owners. Second, South Dakota is the most entrepreneur-friendly state in the nation according to a variety of experts who study such things. Until recently, it was the most economically free state or province in North America and imposed the lowest taxes and regulatory burdens on businesses. Of course I don’t mean to imply that South Dakota is bereft of inventive or innovative entrepreneurs, far from it. Early patents claimed by South Dakotans included everything from mining godevils to bicycle tires suitable for riding over ice to semiautomatic shotguns, each, one imagines, the mother of necessity. A few of the state’s innovative entrepreneurs even made it big. Raven leveraged the state’s salubrious climate and the infatuation of South Dakotans with flight to create a world leading high performance balloon business, for example, while Daktronics became a leader in electronic signs that grace the Olympics and Madison Square Garden. Note that the latter companies are manufacturers. South Dakota is not the Taiwan of the Prairie and likely never will be but it is far from being devoid of manufacturing enterprises. Entrepreneurs have created a very diverse state economy, one that is not dependent on any one sector, not even agriculture. When farmers and ranchers were having a difficult time during the 1970s and 1980s due to increased fuel costs and high nominal interest rates, entrepreneurs, including a political entrepreneur in the form of governor Bill Janklow, stimulated two clean, high paying sectors to take up the slack, finance and health care. Retailing and wholesaling remain important as well, with Sioux Falls, Aberdeen, and Rapid City serving numerous customers from adjacent states like Wyoming, North Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, and Nebraska.South Dakota also earns considerable foreign exchange, if you want to call it that, via its vibrant tourism industry. Two great attractions, one east of the river and the other west of it, attract masses of tourists each year and thousands of other entrepreneurs ride their wide coattails. I speak of course of Mount Rushmore and pheasant country, both of which support numerous hotels, restaurants, and smaller tourist attractions, from infamous “traps” with little to see but much to buy, usually at outrageous prices, to legends like Wall Drug. The Badlands and Black Hills have so many attractions, from the Crazy Horse monument to cavernous cave systems, that tourists can be entertained for weeks on end, even in the winter, or be lured back year after year. And events like the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally and the pheasant opener attract hundreds of thousands of people annually, many of whom spend freely thanks to the pleasant demeanor of most of the state’s tourist entrepreneurs. South Dakota is much more than the Mount Rushmore State, it is the Land of Infinite Variety.Why is South Dakota’s business climate so good for entrepreneurs? For starters, a high density of entrepreneurship tends to replicate itself as family members and friends have plenty of role models and mentors to help them start their own businesses. So, in one sense, South Dakota is full of entrepreneurs today because it has always been well endowed with entrepreneurs, from Paleoindian mammoth hunters to the placer miners of the Black Hills gold rush to the homesteaders of the Great Plains. Another factor is that the state has so little going for it. It needs to foster business or it could very well dry up and blow away, as it almost did during the Great Depression when the state had the dubious distinction of having a higher percentage of its population on the government dole than any other state. As previously noted, South Dakota is almost completely devoid of fossil fuels. Parts of it have good Houdek soil but much of the state is covered in gumbo, which refers to a sticky, hard to work soil, not the delicious Cajun dish. The weather is often delightful – I kid you not, the dry air and open horizon were thought to cause a euphoria called “prairie fever” and to cure all kinds of ailments – but when the weather is not delightful it is often frigging dangerous. East River is at the north end of Tornado Alley and smack in the middle of Hail Hallway, a phrase I just made up. During the winter, wind chills often rival those of Canada. West River’s climate is highly variable. Blizzards can strike in September while January temperatures can rise into the 70s. Nearly 100 degree swings in temperature over the course of a day have been recorded, which is pretty easy when you start the day at negative fiddy. Beauty abounds: from waterfalls to sunsets to prairie and badland vistas to Harney Peak, but that is more of a reason to visit a place than to live there. South Dakota is in the middle of the country by various measures but it isn’t really close to anything of importance. Its population is currently about 850,000, but if it wasn’t for the state’s liberal business laws the population would probably be closer to Wyoming’s, which is under 600,000.But the biggest reason that South Dakota remains business-friendly is state and local government. South Dakotans have made sure that their governments are efficient, at least as governments go. The state’s politicians are accountable to the people and they know it. Citizens hail even governors and U.S. Senators by their first names and don’t hesitate to get into their faces when necessary. Republicans have long ruled the roost but politics is still competitive because of rivalries among various Republican factions and wings. South Dakotans are all for big government in Washington if it means a positive net flow of resources into the state but at home they keep government as small and simple as possible.For example, South Dakotans pay more in user fees than most Americans elsewhere do but that is a good thing: user fees ensure that one part of the community does not subsidize another’s hobby. School funding is traditionally low by national standards but until very recently the outcomes ranged from acceptable to downright good. Except for Sioux Falls in recent years, crime has been low and public amenities have been constructed cheaply compared to elsewhere. Relatively low taxes combined with decent public services attracted many businesses to the state, especially from relatively high tax Minnesota and especially along the I-29 corridor. None of this means that South Dakota will always prosper economically. Some believe that it has been chronically under-investing in education and that the piper will soon have to be paid in the currency of higher crime rates and more unemployment. The large health care sector is vulnerable to shocks emanating from the controversial Affordable Healthcare Act. Pheasant populations are trending downward as more and more farmers destroy key habitat by plowing from ditch to ditch, ripping up shelterbelts, and draining wetlands, rendering South Dakota a veritable Iowa. A return to high fuel prices could cut into tourism along the I-90 corridor, which includes fishing on the Missouri’s manmade lakes as well as the more famous Badlands and Black Hills attractions. My biggest fear at present is that South Dakotans will blow off their own feet by passing ballot initiatives that limit economic freedom and hence entrepreneurship. Last year, a ballot initiative raising the minimum wage and indexing it to inflation passed, as did a health insurance regulation. There is talk now of re-imposing a usury cap of 24 percent. The frightening thing is that even ardent proponents of the minimum wage law admitted that the economic effects of the measure were uncertain but took that to mean that the matter should be pressed forward even though it meant diminishing the liberty of both employers and employees. A repeat regarding the usury cap appears likely. In and of themselves, these measures are unlikely to destroy the state’s prosperity but the precedent that a bare majority of voters, not of eligible voters or the entire population but of people who show up at the polls, can meddle in such intimate affairs could have a chilling effect on business, especially startups and other entrepreneurs vulnerable to populist policy changes such as these. We have to be careful on the policy front because while South Dakota is obviously capable of creating great prosperity it is also capable of generating great poverty. In fact, the state has the dubious distinction of being home to five of the poorest seven counties in the nation. All five are coterminous with, or associated with, Indian reservations such as Rosebud and Pine Ridge. This brings us to the third and most important of the “two Dakotas,” the Euroamerican and the Native American one.Many people don’t consider this final “two Dakotas” because they hold racist or ethnocentric views of the matter. For them, Indians are poor because they are Indians plain and simple or because Indians hold native cultural values. By contrast, I proceed from the assumption that Indians are human beings and that their cultures, like Euroamerican cultures, are on net causes of neither poverty nor prosperity. Because I was impoverished as a youth, I know that driving an old car, drinking alcohol on a daily basis, and being generous to family, friends, and neighbors isn’t an Indian-thing, it is a poor-thing. What allowed me out of the culture of poverty was access to the Euroamerican system of political economy that credibly promised to protect my life, liberty, and property and thus gave me incentives to build my human capital or know-how. What keeps Reservation Indians impoverished is a political economy of poverty imposed upon them from Washington and, to a lesser extent, Pierre, South Dakota’s quaint capital.One myth that I try to dispel in Little Business on the Prairie is the notion that Native Americans are naturally environmentalist-communists who want to remain impoverished. The environmentalist claim is easily disproven by showing evidence that Indians sometimes did not use all of the bison. Sometimes, they just ate the tongue or the fetus and moved on, while capitalist and presumably anti-environment meat processors literally use all parts of every single head of cattle, hog, and chicken. The latter myth, that Indians were communist or a-economic or otherwise disinterested in material gain, I try to dispel by pointing to Indian entrepreneurs both now and in the past. Augustana College anthropologist Adrien Hannus, for example, thinks that the Mitchell site along the James River might prove that Indians processed bison into pemmican en masse and floated it down the James and Missouri Rivers to Cahokia, near present day St. Louis, where they exchanged the preserved meat for pottery and religious services. The Crow Creek massacre site near present day Chamberlain shows that Indians in South Dakota circa 1325 AD engaged in exploitative entrepreneurship but probably also replicative entrepreneurship when “trading” was more lucrative than “raiding.” Indians in what became South Dakota were certainly eager to trade with the new Euroamerican arrivals, first the French, then the British, and finally the Americans. When the U.S. government forced them onto reservations, they eventually gave up their nomadic economy and became successful farmers and, especially, ranchers. By all accounts they would have thrived had not the federal government’s policies stripped them of all incentive to work. Foremost, the federal government never respected Indian property rights, regularly reneging on treaties and cutting into tribal reservation lands. Loss of land continued throughout the twentieth century with the Pick Sloan dam projects – watch the documentary Waterbuster to learn what this did to the incentives of an entire generation of Native Americans -- and up to the present with calls for bison reserves to be carved out of the Pine Ridge Reservation.Allotment, the division of tribal lands into privately-owned parcels, was supposed to provide Indians with incentives to work hard but in the end it led to checker boarding and fractionation. The former means that most reservations are not distinct jurisdictions but rather geographically fragmented political entities that are difficult to discern much less to effectively govern. The latter means that most lands in the hands of individual Indians are, due to the effects of intestate probate laws over generations, owned by too many people, from scores to thousands, to be used to collateralize loans. As a result, most Indians in South Dakota have minimal access to the formal financial system and hence remain unable to finance expansion of their businesses, most of which remain nano-sized.Native Americans eventually became U.S. citizens but a completely separate and unequal system of political economy applied, and continues to apply, to them. Indians have their own health care and education systems, for example, and even in certain confusing circumstances their own criminal laws and business regulations. If Apartheid is too strong a term it is only because the system appears geared toward keeping Indians economically idle rather than cultivating a source of cheap labor as was the case in South Africa. Moreover, some tribes in urban areas were able to turn the separate system of political economy to their advantage by establishing casinos that became quite lucrative. The tribes of South Dakota did likewise, except for the lucrative part. In addition to being located many, many hours of travel from the urban gambling masses, South Dakota’s Indian casinos faced increasingly stiff competition from Deadwood casinos and the ubiquitous electronic gaming casinos that suffuse the state.I see South Dakota, then, as a natural experiment akin to those offered by China, Germany, and Korea in the twentieth century. The experience of those places shows that when people are provided with ample economic freedom, they thrive even in a difficult environment. Squelch that freedom, however, and they wilt from a lack of incentives. Why work hard or smart if you can’t get a loan to grow your business? If you think the government might take what you have built, offering little or nothing in compensation? China spontaneously divided itself into three parts -- mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan – limited freedom on the mainland and allowed it to run amok on the two islands, which combined produced more than the much larger, much more populous, and much more resource rich mainland. Only when the mainland increased economic freedom with Deng Xiaoping’s reforms did it show signs of an economic pulse. Ditto Korea, where the autocratic North is a famine-ridden economic wasteland while the free South is one of the world’s most successful economies. And let’s not forget about Germany, which the victorious Allies arbitrarily divided into East and West following World War II. The communist East foundered economically while the free West surged even though the East was better endowed with factories and natural resources. The exact same outcome in Berlin, located in the economically backward East, showed beyond all doubt that political economy was the key driver of the different economic outcomes, not culture or latitude or anything other than incentives, incentives, incentives.Going forward, therefore, what I would like to see is more, much more, economic freedom for Indians in South Dakota and indeed the entire country. I’d also like to see South Dakota maintain a high level of economic freedom even if that means placing some restrictions on initiated ballot measures. One way would be to limit passage to half of all registered voters, not half of those who turn out to vote. This means that those who want change will have to convince people to turn out and can’t rely, as they have in the past, on apathy. Or, we could restrict initiated ballots only to those laws that increase, rather than decrease, liberty. So legalizing marijuana would be a legitimate use of ballot initiative but banning alcohol consumption would not.Thus concludes my quick romp through South Dakota’s economic history. Little Business on the Prairie contains many more details, especially regarding the development of Rapid City, the metropolis of the West, and Sioux Falls, the metropolis of the East, as well as specific industries including agriculture and agricultural goods processing, construction, mining, transportation, wholesaling, and the like. I hope you pick up a copy, and enjoy it, and remember the other two Dakotas.

Published on April 25, 2015 09:42

March 20, 2015

Cowardly* Chronicle of Higher Education Refuses to Publish an Idea that Could Save Colleges from Failure and End Runaway Tuition Hikes!

3/20/2015 at 4:03 pm Dear Prof. Wright,

Thank you for sending us your article. Several of us have read it, and we regret to say that we are unable to publish it. Because we receive dozens of manuscripts each week on all sorts of topics, we have to make some tough choices. And, unfortunately, that large number also precludes us from responding to each in depth. But we appreciate your thinking of us and hope you will keep us in mind for articles in the future.

Sincerely yours,

The Editors

Small Colleges as Professional Partnerships by Robert E. Wright, Nef Family Chair of Political Economy, Augustana College SDHigher education in America is yet again engulfed in crisis. On the rise for decades, tuition and borrowing appear to be approaching their natural limits. Small colleges are closing or merging and intrusive federal regulations loom. It is time to experiment, especially at the most fundamental level. I’ve argued in two books (including one, Fubarnomics , published in the U.S. in 2010) that the sector’s root problems are ownership structure and incentive alignment. For-profit schools (whether proprietary or publicly-traded) have proven themselves venal: they lure students into taking out federal loans while leaving most to drop out or to earn degrees with little marketplace value. State-owned schools vary greatly in quality and cost-effectiveness. So, too, do private colleges and universities. The problem with both public and private schools is that they are non-profit entities. Nobody owns them, so nobody in particular has an interest in making them more efficient. Some are blessed with talented administrators, caring trustees, generous alumni, and so forth, but none are owned by the people who create most institutional value, faculty members. It is high time that one or more colleges, struggling or recently failed ones, reorganize as professional partnerships, along the lines of a law firm or business consultancy such as McKinsey. Such a college’s assets (tangible and intangible) would be owned by faculty members according to a formula of their own agreement, likely based on variables like term of service, pre-partnership salary, and so forth. Professors who dislike the agreement would be free to leave or to try to negotiate better terms. Presumably those professors who push for more than their objective worth would be allowed to leave while others would receive reasonable recompense for their expected contributions to the partnership. Once bound together in professional partnership, faculty members would be free to establish their own governance rules, policies, and so forth within the general guidelines of partnership law. Partners’ ownership stakes, for example, are not like shares in a public company as they cannot be sold or transferred but only insured against death or disability. The goal of such a rule is to tie the long-term incentives of partners (professors) to that of their firms (colleges). Some flexibility is necessary, however, so in their partnership agreement faculty partners can establish rules governing the “cashing out” of faculty members who wish to leave before retirement, or who the faculty partners wish to be rid of. (Instead of being an absolute, in other words, tenure could be “priced,” as in other types of partnership.) A professional partnership college would be a for-private entity but one where the interests of the two main constituencies, faculty and students, are more closely aligned over the long term than in current for-profit and non-profit ownership models. Publicly-traded and proprietary colleges sometimes make ruthless cuts in their pursuit of quarterly profits. Non-profit public and private colleges, by contrast, often spend too much, i.e., more than strictly necessary to achieve a pedagogical goal, because that can be easier than making difficult decisions. Presumably, professional partners would search out the happy median as they would have no incentive to endanger their own future by slashing expenditures too much or by spending more than they have to in pursuit of specific goals. Surely mistakes will be made in execution of their long-term interests but that is a far better state of affairs than the structurallymis-aligned incentives of traditional non-profit and for-profit colleges.Moreover, I suspect that many professional partnership colleges would soon conclude that their capital would be best employed by lending it to their students or, if they have insufficient reserves to do that, by guaranteeing their students’ college-related debt. Traditional lenders cannot readily discern good student borrowers from risky ones, but colleges certainly can and in fact can make students lower-risk borrowers by increasing their human capital and improving their attachment to their alma mater. Colleges can therefore lower student borrowing costs by lending to their students directly or by guaranteeing student loans made by traditional lenders and in the process tie their long-term interests much more closely to those of their students.Professional partnership colleges could bring other improvements to U.S. higher education as well. If barriers to entry were reduced, we might see increased competition and hence innovations not currently fathomed. The more venal for-profit colleges might be run out of the industry and burdensome federal regulations avoided.Of course, I may have overestimated the beneficial qualities of professional partnerships but, at this critical juncture, we need data more than we need debate. Let the experiment begin and the professional partnership model spread if it works in practice as well as it appears to in theory.

*In hindsight, maybe the editors at the Chronicle are not cowards. Maybe they just aren't very bright.

Thank you for sending us your article. Several of us have read it, and we regret to say that we are unable to publish it. Because we receive dozens of manuscripts each week on all sorts of topics, we have to make some tough choices. And, unfortunately, that large number also precludes us from responding to each in depth. But we appreciate your thinking of us and hope you will keep us in mind for articles in the future.

Sincerely yours,

The Editors

Small Colleges as Professional Partnerships by Robert E. Wright, Nef Family Chair of Political Economy, Augustana College SDHigher education in America is yet again engulfed in crisis. On the rise for decades, tuition and borrowing appear to be approaching their natural limits. Small colleges are closing or merging and intrusive federal regulations loom. It is time to experiment, especially at the most fundamental level. I’ve argued in two books (including one, Fubarnomics , published in the U.S. in 2010) that the sector’s root problems are ownership structure and incentive alignment. For-profit schools (whether proprietary or publicly-traded) have proven themselves venal: they lure students into taking out federal loans while leaving most to drop out or to earn degrees with little marketplace value. State-owned schools vary greatly in quality and cost-effectiveness. So, too, do private colleges and universities. The problem with both public and private schools is that they are non-profit entities. Nobody owns them, so nobody in particular has an interest in making them more efficient. Some are blessed with talented administrators, caring trustees, generous alumni, and so forth, but none are owned by the people who create most institutional value, faculty members. It is high time that one or more colleges, struggling or recently failed ones, reorganize as professional partnerships, along the lines of a law firm or business consultancy such as McKinsey. Such a college’s assets (tangible and intangible) would be owned by faculty members according to a formula of their own agreement, likely based on variables like term of service, pre-partnership salary, and so forth. Professors who dislike the agreement would be free to leave or to try to negotiate better terms. Presumably those professors who push for more than their objective worth would be allowed to leave while others would receive reasonable recompense for their expected contributions to the partnership. Once bound together in professional partnership, faculty members would be free to establish their own governance rules, policies, and so forth within the general guidelines of partnership law. Partners’ ownership stakes, for example, are not like shares in a public company as they cannot be sold or transferred but only insured against death or disability. The goal of such a rule is to tie the long-term incentives of partners (professors) to that of their firms (colleges). Some flexibility is necessary, however, so in their partnership agreement faculty partners can establish rules governing the “cashing out” of faculty members who wish to leave before retirement, or who the faculty partners wish to be rid of. (Instead of being an absolute, in other words, tenure could be “priced,” as in other types of partnership.) A professional partnership college would be a for-private entity but one where the interests of the two main constituencies, faculty and students, are more closely aligned over the long term than in current for-profit and non-profit ownership models. Publicly-traded and proprietary colleges sometimes make ruthless cuts in their pursuit of quarterly profits. Non-profit public and private colleges, by contrast, often spend too much, i.e., more than strictly necessary to achieve a pedagogical goal, because that can be easier than making difficult decisions. Presumably, professional partners would search out the happy median as they would have no incentive to endanger their own future by slashing expenditures too much or by spending more than they have to in pursuit of specific goals. Surely mistakes will be made in execution of their long-term interests but that is a far better state of affairs than the structurallymis-aligned incentives of traditional non-profit and for-profit colleges.Moreover, I suspect that many professional partnership colleges would soon conclude that their capital would be best employed by lending it to their students or, if they have insufficient reserves to do that, by guaranteeing their students’ college-related debt. Traditional lenders cannot readily discern good student borrowers from risky ones, but colleges certainly can and in fact can make students lower-risk borrowers by increasing their human capital and improving their attachment to their alma mater. Colleges can therefore lower student borrowing costs by lending to their students directly or by guaranteeing student loans made by traditional lenders and in the process tie their long-term interests much more closely to those of their students.Professional partnership colleges could bring other improvements to U.S. higher education as well. If barriers to entry were reduced, we might see increased competition and hence innovations not currently fathomed. The more venal for-profit colleges might be run out of the industry and burdensome federal regulations avoided.Of course, I may have overestimated the beneficial qualities of professional partnerships but, at this critical juncture, we need data more than we need debate. Let the experiment begin and the professional partnership model spread if it works in practice as well as it appears to in theory.

*In hindsight, maybe the editors at the Chronicle are not cowards. Maybe they just aren't very bright.

Published on March 20, 2015 14:07

March 18, 2015

***Consumer Alert*** Nagel Property Management Inc., Sioux Falls, SD ***Consumer Alert***

***Consumer Alert*** Nagel Property Management Inc., Sioux Falls, SD ***Consumer Alert***

On occasion, I exercise my First Amendment right to warn friends and neighbors about potentially shady businesses, including hotels and auto dealers who have ripped off my family. That time has come again. Renters and property owners thinking of listing property with Nagel Property Management Inc. of Sioux Falls should beware. Just this afternoon I tried to rent a property through the company only to learn that its leases contain some onerous terms. The company did not send out the lease beforehand so I arrived at the office cashier's check in hand and ready to sign. Several parts of the document and behavior of the company, however, put me on guard. Most importantly, the terms for contract violation were very heavy and breaking the lease inadvertently would be easy to do because it contains sweeping definitions, like banning all forms of "business" activity from the premises. Another clause limits guests to a 2 week stay. The first was easily negotiated but required positive action on my part. The company acted very strangely on the second. We negotiated a change in language from an absolute ban to "written permission" and then to "written notification." Nevertheless, the company tried to sneak a document changed to "authorization" by me, as if I don't know the difference between authorization and notification or that authorization is virtually synonymous with permission. Moreover, it tried to foist on us a second document with many of the same stipulations as the first, including the 2 week guest rule! We had already signed some documents re: security deposit and so forth, so I ripped them up when it became clear that the company was not going to budge on the rule, citing a bunch of bizarre irrelevancies, because I no longer felt I could trust it with my signature. Perhaps worst of all, the company tried to make all sorts of oral, side agreements about the guest rule although its lease clearly states, as it should, that only the written agreement binds.

Of course no one should make a decision about renting a property from, or with, Nagel on the basis of my experience alone but do look over all documents VERY CAREFULLY, know what you are signing, and don't be afraid to walk away if things don't look/feel right.

On occasion, I exercise my First Amendment right to warn friends and neighbors about potentially shady businesses, including hotels and auto dealers who have ripped off my family. That time has come again. Renters and property owners thinking of listing property with Nagel Property Management Inc. of Sioux Falls should beware. Just this afternoon I tried to rent a property through the company only to learn that its leases contain some onerous terms. The company did not send out the lease beforehand so I arrived at the office cashier's check in hand and ready to sign. Several parts of the document and behavior of the company, however, put me on guard. Most importantly, the terms for contract violation were very heavy and breaking the lease inadvertently would be easy to do because it contains sweeping definitions, like banning all forms of "business" activity from the premises. Another clause limits guests to a 2 week stay. The first was easily negotiated but required positive action on my part. The company acted very strangely on the second. We negotiated a change in language from an absolute ban to "written permission" and then to "written notification." Nevertheless, the company tried to sneak a document changed to "authorization" by me, as if I don't know the difference between authorization and notification or that authorization is virtually synonymous with permission. Moreover, it tried to foist on us a second document with many of the same stipulations as the first, including the 2 week guest rule! We had already signed some documents re: security deposit and so forth, so I ripped them up when it became clear that the company was not going to budge on the rule, citing a bunch of bizarre irrelevancies, because I no longer felt I could trust it with my signature. Perhaps worst of all, the company tried to make all sorts of oral, side agreements about the guest rule although its lease clearly states, as it should, that only the written agreement binds.

Of course no one should make a decision about renting a property from, or with, Nagel on the basis of my experience alone but do look over all documents VERY CAREFULLY, know what you are signing, and don't be afraid to walk away if things don't look/feel right.

Published on March 18, 2015 13:05

March 12, 2015

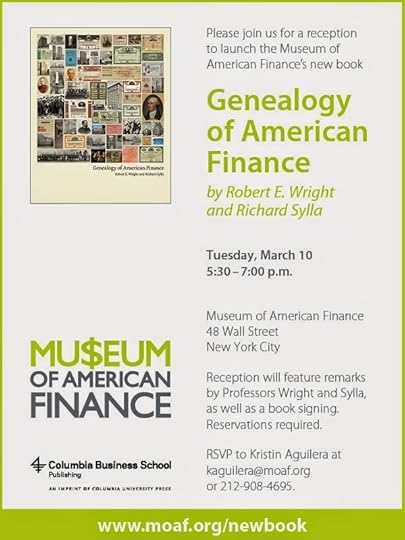

Remarks Made at Book Launch of Genealogy of American Finance

The launch of

Genealogy of American Finance

was very well attended. Below please find the comments I made at the launch, which was held at the Museum of American Finance on the evening of 10 March 2015:

When David Cowen called me two years ago, almost to the day, to ask if a history of bank mergers in the United States could be done, I more or less asked him how much time and money he had available. When he told me, I picked myself up off the floor and said, “yeah, I can do something with that.” Today, I’m very pleased with my response. A year ago, when I was entering almost 2,500 bank and bank holding company mergers for one of our larger banks into an Excel spreadsheet, I fear I would have given a different response, one laden with four letter expletives. But Dick, I think fully half of the Museum’s staff, various unsung heroes at Columbia University Press, and in a few cases bank archivists, did a wonderful job bringing all my work, which ranged from grueling to titillating, to heel. To do so, we had to answer questions like how do we truncate 100s or 1000s of mergers so they fit, not only legibly but elegantly, on a few pages, how do we find images for banks that literally no one involved in the project had ever heard of before the project began, and what does ahorro mean?It means saving in Spanish and it came up because of the methodology we employed to bring the subject matter under control. In an ideal world, with a decade or two to work and a seven figure budget, the project would have traced the history of every bank, commercial, savings, and investment, to ever receive a charter in the United States. A few voluntarily wound up their affairs and some outright failed -- though not as many as you might think. We actually track the aggregate percentages of banks that failed annually from 1790 until 2010 in Table 5. Most banks, in fact, exited by merging with others and mostly in a series of waves driven by momentous economic and/or regulatory changes. Because we could not follow all of the nation’s hundred thousand plus banks forward through time, we opted for the next best alternative, which was to trace mergers backwards from banks still in existence today, much as genealogists do when constructing a family tree. Hence the first part of the book’s title. As there are still thousands of banks in operations in the United States today, writing the histories and recording the mergers of even that population would have taken too long. So we decided to take a page from the Federal Reserve, literally a webpage that unfortunately the Fed has since discontinued, and tackle the fifty largest bank holding companies in the United States as of 2013. I’m very happy that we chose fifty instead of just ten or twenty because the book shows that beneath the big banks that have become to varying degrees famous or infamous over the last few decades there remain sizable, quality institutions with histories just as long and just as interesting as the biggest, hoariest banks you can think of. Hoary just means old, by the way, but I tend to overuse it so the term was completely expunged from the book in editing.Looking at the fifty biggest bank holding companies also took far us away from Wall Street and into our two newest states, Alaska and Hawaii, and two future states, Puerto Rico and Canada. Seriously, our big fifty also includes some big foreign banks with significant U.S. holding companies, world class banks headquartered in places like Spain and Scotland, and Germany and Japan, as well as our very financially stable neighbors to the North. America’s largest 50 bank holding companies include some surprising institutions, including a bank started by the Mormon Church, a giant Dutch cooperative bank, and arguably the world’s best auto insurance company, which is also a mutual. Two other of the BHCs we cover began as insurers and three began their corporate existence as the credit arms of giant manufacturers. Two began as transportation companies and one as a water utility. Another seven started out in finance, though not as commercial banks, including two brokerages, two credit card issuers, two investment banks, and one finance company. That’s why the second part of the book’s title is American Finance instead of Wall Street or the U.S. banking industry.Of course the real world is not as cut and dried as I’ve implied. With but few exceptions for mutuals and relative newcomers, all of the big fifty bank holding companies essentially have multiple points of origin. We did our best to stay with the main strands in the genealogical charts and in the narrative histories but it is not always easy to tell the difference between a merger and an acquisition, especially in older sources, which liked to use general terms like amalgamation instead. Even discerning the target from the acquirer can be difficult. For combinations that took place in recent decades, for example, the Federal Reserve database sometimes indicates that A acquired B while the FDIC database says with equal authority that B acquired A. And what to do when A definitely acquired B but then A changes its name to B? Dick, who has a memory like a steel trap for the full third of American history to which he has been a personal witness, thankfully called me out on at least one of those and we corrected it. But then there were cases where A acquired B and kept A its name but the executives of B took over A’s management. We discuss these subtleties in the narrative histories, of course, but they are not always easily or fully reflected in the genealogical charts or the listings of founding industry or date.The narratives are so rich and plentiful that undoubtedly anyone with an axe to grind or a thesis to promote will find some support in the book’s 300 plus pages, but Dick and I did not come to any grandiose conclusions. Instead we posed a series of questions about economic and regulatory trends. If I had to pick out one underlying theme, though, I’d say that America’s banking system is like a rain forest but instead of providing the biosphere with biodiversity it provides the economy with let’s call it bancodiversity. America’s largest bank has assets roughly 1,000 times the value of the smallest bank in the study but it is arguably no more successful, unless one measures success solely by size. The fact is, a certain portion of America’s depositors and borrowers prefer the smaller bank to the bigger one and the competition makes them both better. If history shows us anything, it is that change is a constant. What works today may utterly fail tomorrow, so it is nice to have alternative models around to fall back upon when financial Armageddon strikes, as we know from recent events it can.We also know from relatively recent events that Wall Street faces physical risks. Thankfully, our nation’s bancodiversity is geographic as well as cultural, organizational, and technical. America’s big bank human capital spreads from Portland, Maine to San Juan, Puerto Rico to Honolulu, Hawaii and from San Francisco to Minneapolis to Houston to Boston and surprising places in between, including Tulsa, Oklahoma; Des Moines, Iowa; Birmingham, Alabama; Columbus, Ohio; Bridgeport, Connecticut, and even my old stomping grounds in Buffalo, New York. Maybe an interest in bancodiversity is what induced the Fed to replace its top fifty bank holding company page with a page listing holding companies with assets greater than $10 billion, which throws big mutuals like Teacher’s Insurance & Annuity Association and State Farm into the mix as well. Since we have gone to press, some real world changes have also taken place. American Express is struggling again, a recurrent theme in its history. Royal Bank of Scotland spun off Citizens, which is now Citizens Financial Group, Inc. and the nation’s 23rd largest BHC. Unionbancal changed its moniker to MUFG Americas Holdings Corporation and moved its headquarters to New York. M&T and Hudson City Bancorp still want to merge but find their marriage blocked by the Fed. And so forth. This is all fodder, perhaps, for a second edition of this book but of course that will depend on how the first is received. I think every bank executive, regulator, financial policymaker, and financial journalist in North America and Europe should have a copy handy, but that’s just me. Thanks!

When David Cowen called me two years ago, almost to the day, to ask if a history of bank mergers in the United States could be done, I more or less asked him how much time and money he had available. When he told me, I picked myself up off the floor and said, “yeah, I can do something with that.” Today, I’m very pleased with my response. A year ago, when I was entering almost 2,500 bank and bank holding company mergers for one of our larger banks into an Excel spreadsheet, I fear I would have given a different response, one laden with four letter expletives. But Dick, I think fully half of the Museum’s staff, various unsung heroes at Columbia University Press, and in a few cases bank archivists, did a wonderful job bringing all my work, which ranged from grueling to titillating, to heel. To do so, we had to answer questions like how do we truncate 100s or 1000s of mergers so they fit, not only legibly but elegantly, on a few pages, how do we find images for banks that literally no one involved in the project had ever heard of before the project began, and what does ahorro mean?It means saving in Spanish and it came up because of the methodology we employed to bring the subject matter under control. In an ideal world, with a decade or two to work and a seven figure budget, the project would have traced the history of every bank, commercial, savings, and investment, to ever receive a charter in the United States. A few voluntarily wound up their affairs and some outright failed -- though not as many as you might think. We actually track the aggregate percentages of banks that failed annually from 1790 until 2010 in Table 5. Most banks, in fact, exited by merging with others and mostly in a series of waves driven by momentous economic and/or regulatory changes. Because we could not follow all of the nation’s hundred thousand plus banks forward through time, we opted for the next best alternative, which was to trace mergers backwards from banks still in existence today, much as genealogists do when constructing a family tree. Hence the first part of the book’s title. As there are still thousands of banks in operations in the United States today, writing the histories and recording the mergers of even that population would have taken too long. So we decided to take a page from the Federal Reserve, literally a webpage that unfortunately the Fed has since discontinued, and tackle the fifty largest bank holding companies in the United States as of 2013. I’m very happy that we chose fifty instead of just ten or twenty because the book shows that beneath the big banks that have become to varying degrees famous or infamous over the last few decades there remain sizable, quality institutions with histories just as long and just as interesting as the biggest, hoariest banks you can think of. Hoary just means old, by the way, but I tend to overuse it so the term was completely expunged from the book in editing.Looking at the fifty biggest bank holding companies also took far us away from Wall Street and into our two newest states, Alaska and Hawaii, and two future states, Puerto Rico and Canada. Seriously, our big fifty also includes some big foreign banks with significant U.S. holding companies, world class banks headquartered in places like Spain and Scotland, and Germany and Japan, as well as our very financially stable neighbors to the North. America’s largest 50 bank holding companies include some surprising institutions, including a bank started by the Mormon Church, a giant Dutch cooperative bank, and arguably the world’s best auto insurance company, which is also a mutual. Two other of the BHCs we cover began as insurers and three began their corporate existence as the credit arms of giant manufacturers. Two began as transportation companies and one as a water utility. Another seven started out in finance, though not as commercial banks, including two brokerages, two credit card issuers, two investment banks, and one finance company. That’s why the second part of the book’s title is American Finance instead of Wall Street or the U.S. banking industry.Of course the real world is not as cut and dried as I’ve implied. With but few exceptions for mutuals and relative newcomers, all of the big fifty bank holding companies essentially have multiple points of origin. We did our best to stay with the main strands in the genealogical charts and in the narrative histories but it is not always easy to tell the difference between a merger and an acquisition, especially in older sources, which liked to use general terms like amalgamation instead. Even discerning the target from the acquirer can be difficult. For combinations that took place in recent decades, for example, the Federal Reserve database sometimes indicates that A acquired B while the FDIC database says with equal authority that B acquired A. And what to do when A definitely acquired B but then A changes its name to B? Dick, who has a memory like a steel trap for the full third of American history to which he has been a personal witness, thankfully called me out on at least one of those and we corrected it. But then there were cases where A acquired B and kept A its name but the executives of B took over A’s management. We discuss these subtleties in the narrative histories, of course, but they are not always easily or fully reflected in the genealogical charts or the listings of founding industry or date.The narratives are so rich and plentiful that undoubtedly anyone with an axe to grind or a thesis to promote will find some support in the book’s 300 plus pages, but Dick and I did not come to any grandiose conclusions. Instead we posed a series of questions about economic and regulatory trends. If I had to pick out one underlying theme, though, I’d say that America’s banking system is like a rain forest but instead of providing the biosphere with biodiversity it provides the economy with let’s call it bancodiversity. America’s largest bank has assets roughly 1,000 times the value of the smallest bank in the study but it is arguably no more successful, unless one measures success solely by size. The fact is, a certain portion of America’s depositors and borrowers prefer the smaller bank to the bigger one and the competition makes them both better. If history shows us anything, it is that change is a constant. What works today may utterly fail tomorrow, so it is nice to have alternative models around to fall back upon when financial Armageddon strikes, as we know from recent events it can.We also know from relatively recent events that Wall Street faces physical risks. Thankfully, our nation’s bancodiversity is geographic as well as cultural, organizational, and technical. America’s big bank human capital spreads from Portland, Maine to San Juan, Puerto Rico to Honolulu, Hawaii and from San Francisco to Minneapolis to Houston to Boston and surprising places in between, including Tulsa, Oklahoma; Des Moines, Iowa; Birmingham, Alabama; Columbus, Ohio; Bridgeport, Connecticut, and even my old stomping grounds in Buffalo, New York. Maybe an interest in bancodiversity is what induced the Fed to replace its top fifty bank holding company page with a page listing holding companies with assets greater than $10 billion, which throws big mutuals like Teacher’s Insurance & Annuity Association and State Farm into the mix as well. Since we have gone to press, some real world changes have also taken place. American Express is struggling again, a recurrent theme in its history. Royal Bank of Scotland spun off Citizens, which is now Citizens Financial Group, Inc. and the nation’s 23rd largest BHC. Unionbancal changed its moniker to MUFG Americas Holdings Corporation and moved its headquarters to New York. M&T and Hudson City Bancorp still want to merge but find their marriage blocked by the Fed. And so forth. This is all fodder, perhaps, for a second edition of this book but of course that will depend on how the first is received. I think every bank executive, regulator, financial policymaker, and financial journalist in North America and Europe should have a copy handy, but that’s just me. Thanks!

Published on March 12, 2015 14:26

March 5, 2015

Business History > Piketty

I just posted this to SSRN. To download the full (short) paper, click here.

Business History > Piketty

Robert E. Wright

Augustana College - Division of Social Sciences

March 2, 2015

Abstract:

Piketty's Capital in the 21st Century has attracted more attention than it perhaps deserves given that its main empirical claim, that wealth inequality is bound to occur in "capitalist" economies because the rate of return r is greater than the rate of economic growth g (r > g), is not rigorously shown and explicitly excludes capital losses. Over the last few centuries, returns in the United States have varied greatly by asset class and often been highly negative. Moreover, while the book correctly maintains that recent increases in income inequality in the United States are due to poor corporate governance, it calls for a general wealth tax rather than governance reform.

Number of Pages in PDF File: 11

Keywords: Thomas Piketty; Capital in the 21st Century; wealth inequality; income inequality; corporate governance; rates of return

JEL Classification: D63, G3, N11, N12, N21, N22 , O15, P1

Business History > Piketty

Robert E. Wright

Augustana College - Division of Social Sciences

March 2, 2015

Abstract:

Piketty's Capital in the 21st Century has attracted more attention than it perhaps deserves given that its main empirical claim, that wealth inequality is bound to occur in "capitalist" economies because the rate of return r is greater than the rate of economic growth g (r > g), is not rigorously shown and explicitly excludes capital losses. Over the last few centuries, returns in the United States have varied greatly by asset class and often been highly negative. Moreover, while the book correctly maintains that recent increases in income inequality in the United States are due to poor corporate governance, it calls for a general wealth tax rather than governance reform.

Number of Pages in PDF File: 11

Keywords: Thomas Piketty; Capital in the 21st Century; wealth inequality; income inequality; corporate governance; rates of return

JEL Classification: D63, G3, N11, N12, N21, N22 , O15, P1

Published on March 05, 2015 07:58

February 19, 2015

Even Better Than a Balanced Budget Amendment Would Be a No More Presidential Family Dynasties Amendment

As noted in an earlier post, I'm skeptical of a federal balanced budget amendment. I'd rather see a return to the Fiscal Constitution described by Bill White. The matter is much more complex than the 22nd amendment, which established a two-term limit for U.S. presidents.

What I would like to see, though, is an end to presidential family dynasties. I think an amendment that would give real meaning to the 22nd amendment by banning the children, parents, siblings, and spouses of presidents from serving as president (or vice president) would be very helpful in the long run and in the short run would prevent the horror of another Bush, Clinton, or Obama (don't think they haven't thought about it) in the White House. The simple fact is that thousands, if not tens of thousands, of people could serve as president with distinction. (And untold others could muddle through like the last two did.) So why risk de facto breaking the 22nd Amendment (by electing a person effectively controlled by a former 2-term president), looking bad to foreigners (or more importantly to future Americans!), and perpetuating presidential family dynasties? Costs > benefits.

Would such an amendment be unfair to the children, parents, siblings, and spouses of presidents? Yes, but it would be less unfair than the name recognition, patronage, and other boosts that those close to presidents receive. Would Hillary have been Secretary of State without Bill's presidency? Nope. Would George W. have won if daddy didn't? Nope. (In fact, he didn't really win the first time!) John Quincy rode on his old man's coattails too, and didn't really win his election either.

What I would like to see, though, is an end to presidential family dynasties. I think an amendment that would give real meaning to the 22nd amendment by banning the children, parents, siblings, and spouses of presidents from serving as president (or vice president) would be very helpful in the long run and in the short run would prevent the horror of another Bush, Clinton, or Obama (don't think they haven't thought about it) in the White House. The simple fact is that thousands, if not tens of thousands, of people could serve as president with distinction. (And untold others could muddle through like the last two did.) So why risk de facto breaking the 22nd Amendment (by electing a person effectively controlled by a former 2-term president), looking bad to foreigners (or more importantly to future Americans!), and perpetuating presidential family dynasties? Costs > benefits.

Would such an amendment be unfair to the children, parents, siblings, and spouses of presidents? Yes, but it would be less unfair than the name recognition, patronage, and other boosts that those close to presidents receive. Would Hillary have been Secretary of State without Bill's presidency? Nope. Would George W. have won if daddy didn't? Nope. (In fact, he didn't really win the first time!) John Quincy rode on his old man's coattails too, and didn't really win his election either.

Published on February 19, 2015 11:22

February 12, 2015

The Economics of Slavery and Freedom, 1750-2050

The Economics of Slavery and Freedom, 1750-2050

3 in 1 Room, Augustana College SD, Thursday, 12 February 2015, 7 p.m.I was ten years old when I first went to work. … There were five people in the home, and I did all the work – cooking, cleaning, washing clothes, washing dishes. I woke each morning at 5 A.M. and went to sleep at 10 P.M. I slept on the floor in the drawing room. I did this work seven days a week. Sometimes the wife would beat me. The husband in the home would rape me. … After two years, they sent me to another home. … I was in this home for two years. They did not beat me, but I was working all the time. Finally, I was in a third home for three years. I had to do everything. They had two daughters, and I had to take them to school each morning. I wished I could go to school like them. In this home they would beat me very badly.If pressed on, say, a game show, many people would date the passage I just read to the nineteenth century or earlier because the speaker was clearly enslaved: beaten, raped, forced to work long hours for others who denied her an education. Unfortunately, the narrative is actually from the present century. It is part of the haunting story of Nirmala, a young girl from Nepal, as recorded by Siddarth Kara, a Harvard University professor and one of the world’s foremost experts on human trafficking and contemporary slavery.

A specter haunts the world – the specter of slavery. This is a serious matter, though I’m teasing a bit by invoking Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto. You were probably taught, as was I, that slavery was a quote unquote peculiar institution that flourished in America for a few centuries before Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant ended it once and for all. If you are a history geek, you’ll know that matters were a little messier than that – slavery pervaded the New World and the freedpeople and their progeny suffered for decades after Emancipation – but the basic Whiggish view that slavery is a relic of the past still likely dominates your view of the matter. My goal tonight is to disabuse you of the notion that slavery is something that happened in the past to the ancestors of a readily identifiable group and to help you to see that American chattel slavery was not peculiar at all. Rather, it was part and parcel of a long and continuing history of forced or coerced labor. As Sigmund Freud once wrote, Homo homini lupus … man is wolf to man.

I hope that by the end of the evening you will be so outraged that you will want to spring to action, or at least be interested enough in the topic to attend the other lectures in this series, which is sponsored by the Institute for Humane Studies at George Mason University in Virginia, near the nation’s capital. All that the Institute requests in return for its money, which will be used to pay the travel expenses and honorariums of all the speakers except me, because I’m doing this for free and live nearby, is the acknowledgement just made, a headcount, a few pictures of the event, and the paper survey being passed around. All students who complete a survey and provide a valid email address will be entered to win a $25 Amazon gift card. Yes, this means you will receive an email from the Institute. If you don’t want it, you can of course unsubscribe as it would be ridiculous for an organization dedicated to advancing human liberty to force people to accept electronic junk mail. Yes, you are allowed to laugh. Finally, if you have any questions about liberty, or want to learn more about its role in our society, I am the “go to person” for the Institute here at Augustana so feel free to contact me via email, Twitter, Skype, my website, or my office, which is 111 Madsen Center, just to the north of the Social Science division main office on the first floor.

I should also take this opportunity to thank four of the students in my interim course on global slavery who helped me with this speech, Augie history majors Gabe Dunn and Dan Jansen, Augie economics major Cephas Mampuya, and St. Thomas economics major Nicole Niedringhaus. Any remaining mistakes or lame jokes, however, remain my sole responsibility. See that last comment was actually a lame joke that only professors would get.

Anywho, thanks to the funding provided by the Institute for Humane Studies, exactly a month from tonight, in this very room, historian Matthew Mason of Brigham Young University will talk about the politics of abolition in historical context. On April 9, literature professor Elizabeth Swanson Goldberg of Babson College in Massachusetts will show how businesses can help to reduce the incidence of slavery. And on May 7, again right here in the 3-in-1 Room, economic historian John Majewski of the University of California, Santa Barbara, will discuss his work on the hidden economic costs of slavery. If the continued enslavement of other human beings somehow does not morally outrage you, John will show you how slavery hits everyone squarely in the pocketbook.At this point, some of you are probably wondering what exactly I mean by terms like enslavement, slave, and slavery. Most broadly, I mean the term literally, not metaphorically, and regarding labor, not politics. Phrases like “I slaved away on the project” or we “worked like slaves” are obviously just metaphorical and hence not the subject under discussion this evening. Before their War for Independence, many of the colonists of mainland North America claimed that King George, the British Parliament, and London bureaucrats were trying to enslave them by limiting the colonists’ political influence over fiscal, monetary, and other public policies. That is obviously an important topic, one that I have been writing a book about for 15 years now, but not the subject tonight, though admittedly finding the boundary between political enslavement and labor slavery can be difficult, particularly when a government owns labor slaves, as many have done throughout history, including Germany and Japan during the Second World War. I would assert that North Korea is the worst offender today, but I won’t for fear that its hackers will shut down my blog, on which this speech will be posted … minus the sentence I just spoke of course. Let me remind you that you are free to laugh when appropriate.

What I mean tonight by enslavement is the practice of forcing people to labor for others. Slaveholders, a.k.a. enslavers, are businesses, governments, or individuals who claim to own human beings or a unilaterally decided portion of the economic value created by their labor. Slaves, a.k.a. enslaved persons, are the people that enslavers purportedly own and de facto expropriate the labor of. Right now, so far as the best experts can tell, about 30 million people are enslaved throughout the world. 30 million! That figure may be higher than at any other time in human existence. Of course 30 million is a small percentage of the global population, which is now a record 7.3 billion, so we can’t rightly say that slavery is more prevalent than ever before. But it is still 30 million souls, roughly the population of both Dakotas, Colorado, Montana, Wyoming, Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, Minnesota, and Wisconsin combined. That is almost as many people as have died of AIDs since its global proliferation began in the 1970s. Slavery appears to be spreading as quickly as HIV and in fact the two phenomena are linked because sex slaves, a sizeable portion of the 30 million total slaves, can’t insist on condom use or other safe sex practices.

Another way to think of the 30 million figure is that it is less than one percent of the world’s population. Yet and I quote here Nobel Laureate Robert Fogel: quote between 1600 and 1800, New World slaves represented less … than 1 percent of the world’s population. unquote Nevertheless, by the end of that period slavery was rightly considered one of the world’s most pressing problems. In short, slavery today is already a major problem and likely to get worse before it gets better, especially if good people like yourselves stand idly by.

Before I explain the economic reasons why slavery, if left unchecked, is likely to continue to spread, however, I want to continue to explain what is meant by the term as some of you may be picturing shackled Africans picking cotton or other iconic images from America’s checkered past. It is Black History Month after all. But slavery today looks different from that depicted in Twelve Years a Slave or Roots because enslavement is technically illegal the world over but no government has managed to extirpate it. De jure, there are no slave and free states or countries anymore but de facto all are slave states because slaves can be found in every country on the globe and every state in the United States, including South Dakota.

Some of you may find it difficult to believe that South Dakota is a slave state because if you drive from Sioux Falls to Pierre you won’t see gangs of slaves tending to the fields. Slaves today usually work indoors, or at least out of sight, and at a wide range of activities, not just growing and harvesting agricultural staples. Many girls and young women, and some boys, are forced to sell sexual access to their bodies and forced prostitution has been documented in this state on several notorious occasions. We can call South Dakota a free state when we have made it so costly to enslave other people here that no one would even think of trying it. Cost, by the way, is a function of both the penalties for enslaving others, including jail time and fines, and the probability of being caught and convicted. Passing harsher penalties, in other words, is meaningless if enslavers know they remain unlikely to be convicted.

Other forms of slavery may also occur in good, old So. Dak. We know that elsewhere in the world, some enslaved individuals are forced to beg and to turn over the proceeds to their masters at the end of the day. Others make simple manufactured goods like bricks, cigarettes, and textiles. Others are forced to fish or raise shrimp. Any good that is relatively easy to produce can be made by slave labor, and probably is, at least somewhere.

Slavery today has no racial component per se. Enslaved persons are more likely to come from oppressed minorities and poor communities than from affluent, mainstream groups, but slaveholders are equal opportunity enslavers. Today, people of every race, religion, and ethnic group are enslaved and people of every major race, religion, and ethnic group hold slaves. That was pretty much true in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as well, though you may not have heard much about Muslims enslaving Europeans and Americans, the use of Asian coolies in Latin America, the serfs beholden to Russia’s Tsar, and so forth, but they are all part of humanity’s not so illustrious and not so distant past.

Nobody knows when slavery began but anyone familiar with The Holy Bible, the Quran, or the holy texts of the major Asian religions knows that it is an ancient practice. In fact, the first human writings, from the Epic of Gilgamesh to the Code of Hammurabi, are rife with mentions of slaves and slavery. Thanks to the discovery of iron shackles in eastern Europe, we know that slavery existed in prehistory, although the details remain obscure. Slavery probably arose during the Neolithic Revolution, as some groups of humans shifted from a hunting and gathering foraging strategy to herding and horticulture and, in some areas, outright agriculture. It is difficult to see how or why hunter-gatherers would enslave others, except perhaps for sexual recreation or procreation, and indeed a survey of remaining hunter-gatherer societies conducted in the twentieth century revealed that virtually none of them countenanced slavery. Most remaining pastoral and agricultural societies, by contrast, had allowed slavery in the past and some had made extensive use of slaves.

In fact, slavery may be one of the defining characteristics of our species, along with trading. Adam Smith’s observation that humans are the only critters that regularly trade with unrelated conspecifics, to wit with other members of the species that are not part of the same kin group, holds up to this day. So too, however, does the observation that human beings are the planet’s most prolific enslavers. We are consummate warriors, too, but all wars eventually end while trade and slavery just go on and on and on. From this broader biological and historical perspective, it is not at all surprising that slavery remains so ubiquitous today.

But are there really some 30 odd million people enslaved today? Well, that figure is not based on census counts as in early nineteenth century Trinidad, the antebellum U.S., Brazil before its emancipation, and so forth because, again, slavery is everywhere illegal. Measuring illicit activities is notoriously difficult, but I think the order of magnitude is correct. We are not talking about 1 million people here, nor 100 million. Whether the right number is 15 million or 45 million, slavery is an important problem demanding our attention, especially because the number of enslaved persons is more likely to grow than to shrink unless good people act.

A more interesting question than the number of slaves, I think, is the degree to which people are enslaved. Thinking about the degree of enslavement might strike you as a strange notion as the traditional belief in this country is that people are either free or they are enslaved and that was certainly the case of the iconic New World slavery of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. But if we look at slavery more broadly throughout the globe and human history, it quickly becomes apparent that people can be forced to labor for others in many different ways. In New World slavery, as in the United States before ratification of the 13th Amendment exactly 150 years ago this December, slaveholders used all known methods of coercion and control. Employers of other forms of forced labor utilize fewer methods, allowing the worker somewhat more leeway or freedom.Armed with that insight, I constructed a degree of slavery index that takes the form of 17 characteristics of enslavement. I don’t want this to sound too flippant but I feel we need a brief interlude of comic relief so here goes: my slavery index is sort of like the “You might be a redneck if” jokes that were popularized by Jeff Foxworthy over a decade ago. I happen to be a redneck so I have no problem repeating some of them here:· You might be a redneck if you’ve ever been kicked out of the zoo for heckling the monkeys. That actually happened to me but in my defense the monkeys started it!· You might be a redneck if you have the local taxidermist’s number on speed dial. If you don’t believe this one, you haven’t seen my office lately.· You might be a redneck if you’ve ever hit a deer with your car...deliberately. Okay, I have not done this recently but I have tried to clip roosters and rabbits, only in open season, though, and only when they were too close to buildings or livestock to shoot them instead.