Robert E. Wright's Blog, page 2

August 15, 2023

Worker Productivity Through the Ages

NB: 100% sure I wrote this but I don't recall when or why! Found it on my Google Drive. Pretty sure it isn't published anywhere.

Worker Productivity Through the Ages

Productivity is generally defined as total output divided by total input, which can be stated in terms of time or some unit of currency. If output increases (decreases) while input stays constant, or if output increases faster (slower) than inputs, productivity rises (falls). Productivity is related to, but should not be confused with, efficiency, which is the expected input divided by actual input needed to achieve some level of output, often stated in percentage terms by multiplying by 100.

Despite its simple definition, productivity remains so difficult to meaningfully measure that economists generally treat it as a residual by lumping the productivity of different types of workers into total factor productivity (TFP), the portion of increases in output not explained by increases in inputs (more formally, Y = A*K*L, where Y is total output, A is TFP, K is capital’s share of input, and L is labor’s share of input) (Comin 2008). Increases in TFP can usually be linked to specific technological advances, as Shackleton does for the USA after 1870 (Shackleton 2013). Economists generally dislike measures of worker productivity, however, because most merely measure the efficiency of individual workers, while others compute averages instead of the productivity of the marginal worker, i.e., the last worker toiling to complete some task. For over a century, economists have argued that marginal analysis trumps the analysis of averages or other central tendencies. (Harry Jerome, “The Measurement of Productivity Changes and the Displacement of Labor,” American Economic Review 22, 1 (March 1932): 32-40; George Stigler, “Economic Problems in Measuring Changes in Productivity” in NBER, Output, Input, and Productivity Measurement [Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961], 47-78.)

In short, productivity measurement remains inherently contextual, varying with the question the measurer seeks to address as well as the physical realities of different workplaces and spaces (Sena 2020). Measurements appropriate for one time and place may prove entirely inappropriate, or downright impossible, for another. Even simple measures of labor productivity, like output per unit of time, can depend crucially on raw material input availability, incentives to work, market demand, and seasonality. Output quality must also be considered, especially when concepts like minimal acceptability are unavailable or inappropriate.

This section, “Worker Productivity Through the Ages,” provides important examples of the changing contextuality of productivity from humanity’s origins through the Neolithic Revolution to ancient historical civilizations and the modern productivity revolutions in agriculture, communication, manufacturing, and transportation, to the recent domination of labor share by construction, government, and knowledge workers.

Prehistoric Productivity

Early humans (hominins) coevolved with their technologies to the point that modern humans themselves could be considered the first general purpose technology (GPT-HS). It appears likely that evolution by means of natural selection drove early humans to use productivity gains – perhaps from technologies like fire or other ways of denaturing/predigesting food (Sanfelice and Temussi 2016), stone tools (Semaw et al. 2009), and trade – to biologically purchase bigger, more complex brains capable of developing yet more sophisticated technologies or of producing existing technologies more efficiently (Ofek 2001)(Wilson 2020). The medium of purchase was calories and the other nutritional inputs needed to grow and fuel brains, which are biologically expensive (Kotrschal et al. 2013). While the precise timing and mechanisms remain unknown, hominin encephalization certainly occurred over several million years as average brain volume grew faster than body weight, from 440 cc to over 1,300 cc. From impressions left on fossil craniums, scientists know that hominin brains also grew more complex as human-technology coevolution occurred (Rightmire 2009; Gunz et al. 2020; Tarlach 2020; Price 2021).

Except for stone and bone tools and hearths (fire pits), most early human technologies left little or no direct evidence in the archeological record. Although measuring stone or bone tool production productivity in the modern sense will remain impossible, scientists have estimated manufacturing efficiency by modeling the ratio of waste rock to useful blades, or length of cutting edge to original stone mass, after reconstructing the knapping or fracturing process employed. Some conduct experiments by knapping rocks themselves using the same tools and techniques that early humans did, and comparing the results to archeological data taken from ancient lithic quarries and tool manufacturing sites (Schlanger 1996).

Scientists have generally found gradual increases in raw material efficiency over lithic technological evolution (Castañeda 2016; Muller and Clarkson 2016). Other specialists have performed similar experiments on bone tools (Karr 2015; Karr and Outram 2015). The complexity of stone and bone tools has also been quantified and shown to have increased over time (Perreault et al. 2013), as exemplified by lithic miniaturization, or the production of microliths – very small stone tools with high cutting efficiency by weight (Pargeter and Shea 2019).

Similarly, while scientists will never know with certainty how long it took early humans to start or maintain fires (Alperson-Afil 2017), they can discern which fuels were used. Iron Age farmers in northwestern continental Europe, for example, used all available fuel sources: dung, peat, and wood (Braadbaart et al. 2017). The efficiency of hearth construction (Black and Thorns 2014; Graesch et al. 2014) and hearth placement in caves and manmade structures (Kedar et al. 2020; Kedar et al. 2022) has also been measured by comparing experimental to archaeological data (Brodard et al. 2016).

Measuring the productivity of hunting and gathering remains fraught because the amount of time it took to acquire sufficient food, clothing, and tool materials was undoubtedly partly a complex function of the ratio of the human population to target species and the intensity of trade networks (Deino et al. 2018). Scientists presume, however, that more complex technologies increased productivity by making it easier/faster to harvest animals as well as sundry vegetable materials like fruits, nuts, seeds, and tubers. The ability to haft stone points, for example, allowed early human hunters to more effectively kill large game animals starting half a million years ago (Wilkins et al. 2012), while the ability to create cordage from animal sinews or vegetable matter allowed them to make better clothing, carry packs, mats, huts/homes, and even boats (Hardy et al. 2020). Indeed, new evidence suggests that over 40,000 years ago some human groups regularly caught pelagic fish (e.g., tuna), implying both deep sea boating and fishing technologies (O’Connor et al. 2011).

Such improved technologies rendered early humans more productive, freeing their time to develop yet more complex technologies, plus cultural goods that both displayed and aided their conceptual prowess in ways too complex and distant to be disentangled (Wadley 2013).

Productivity Gains During the Neolithic Transition to Agriculture

Early humans were productive enough to survive and spread across most of the Old World (Deino et al. 2018; Gunz et al. 2009). Although population estimates vary, genetic and ecological studies indicate that early humans clearly were less populous than humans today (Huff et al. 2010). Adoption of agriculture, the domestication and deliberate production of numerous plant and animal species, drove additional technological changes, like those associated with small-scale metallurgy and manufacturing (Moorey 1999), that eventually made higher human population levels possible.

Scientists still do not fully understand, however, why the Neolithic Revolution, the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture, occurred when and why it did (Weisdorf 2005) because farming initially meant more work, higher incidences of disease, and increased mortality (de Becdelièvre et al. 2021). It increasingly appears that small groups grew into farming over time instead of transitioning in large numbers in a single generation as sometimes supposed. Herding and hunting were complimentary activities, as were fishing and farming, suggesting that mixed subsistence strategies could sustain growing populations until agricultural productivity in the richest agricultural areas improved due to learning-by-doing, increased climatic stability (Matranga and Pascali 2021), and perhaps improved property rights (Bowles and Choi 2019; Bowles and Choi 2013).

Measuring Productivity in the Ancient Historical Era

The ancient Chinese, Greeks, Indians, Mayans, Mesopotomians, Persians, and Romans invented several crucial new general purpose technologies, including writing (Bywater 2013) and mathematics (Boyer and Merzbach 1993; Cuomo 2005), that increased productivity directly and also led to new or greatly improved specific technologies (Krebs 2004). The Romans, for example, developed or improved boats, wheeled vehicles, water-lifting technologies, and watermills, among many other technologies (Greene 1990), while the Greeks invented coins, a mechanical astronomical computer, and napalm, among other things (Freeth et al. 2021).

Although all flourished during golden ages, typically periods characterized by high levels of economic freedom (Bergh and Lyttkens 2014), none of those civilizations experienced the sustained, across-the-board increases in TFP associated with modern economies. Indeed, many collapsed politically and economically for reasons not fully understood (Tainter 1988). Some may have succumbed to the sunk cost fallacy, clinging to old habits and habitations even after they became environmentally untenable (Janssen and Scheffer 2004). Others appear to have suffered from the increased power of rent seeking institutions that constrained property rights and thus limited incentives to innovate (Westermann 1915; Bó et al. 2015).

Productivity in the Age of Economic Revolution

After the demise of the ancient civilizations, the productivity of agricultural workers stagnated, though subject to intermittent reversals and shocks like the Black Death (Jonathan Jarrett, “Outgrowing the Dark Ages: Agrarian Productivity in Carolingian Europe Re-evaluated,” Agricultural History Review 67 (2019): 1-28.) Introduction of the heavy plow around 1000 AD, for example, allowed for more extensive cultivation in Northern Europe that aided nascent urbanization and hence economic specialization, long considered a driver of non-agricultural productivity increases (Andersen et al. 2016).

Starting in Holland in the seventeenth century, rapid increases in agricultural productivity freed up farmers, and especially their children, to work in emerging or rapidly growing industries, including those in the trade, transportation, industrial, and communication sectors. Eventually, those sectors also shed workers as technology-induced productivity increases rendered their labor unnecessary (Ville 1986).

Agricultural productivity increases stemmed only in part from mechanization (Collins and Thirsk 2000), productivity increases in which were often driven by competition between small farm implement manufacturers (Binswanger 1986). At first, productivity increases derived mainly from improved techniques and seeds (Olmstead and Rhode 2008), as well as productivity improvements in fencing, ditching, and draining (Baugher 2001). Although it proved difficult to compare agricultural productivity internationally, slower agricultural productivity growth clearly constrained economic, especially industrial, development in twentieth-century Europe (O'Brien et al. 1992; Cosgel 2006) and elsewhere (Baumol 1987). Countries with robust increases in agricultural productivity, like the USA, by contrast, also experienced rapid increases in industrial productivity (Broadberry 1994; Broadberry and Irwin 2004).

Following Marx and others (Shantz et al. 2014), many scholars have assumed that industrialization, especially under the so-called “scientific management” principles of Frederick Taylor and his disciples (Gilbreth 1914), alienated and de-skilled workers, turning them from GPTs into the appendages of machines. Evidence of large scale de-skilling over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries remains scant (Form 1987), though deskilling may cycle (Sabel and Zeitlin 1985), increasing when disruptive new technologies proliferate rapidly but declining over time as workers learn to troubleshoot and fix the machines they tend and feed with raw materials or data (Form and Hirschhorn 1985).

Just as productivity increases freed agricultural workers to move into industrial jobs, productivity increases freed industrial workers to move into government and service jobs and to morph into “knowledge workers” who rely on the power of their brain rather than their brawn.

Difficulties Measuring the Productivity of Knowledge and Government Workers

In the second half of the twentieth century, knowledge workers came to dominate labor share in leading economies like that of the USA (Drucker 2018; Cortada 2009). Government workers, including direct employees and contractors, also became an increasingly large percentage of the workforce in many countries after World War II (Light 2019).

To this day, it remains difficult to measure the productivity of knowledge workers (Ramírez and Nembhard 2004), in part because worker inputs cannot be easily discerned. Engineers, for example, may be physically present at work but mentally absent (Jones and Chung 2006). Ditto financial services providers (Zieschang 2018). Construction industry productivity also fluctuates due to mental inattentiveness to measurements and plan details (Motwani et al. 1995). Measuring the productivity of nurses also remains difficult because of the mixed physical-mental nature of their jobs and the necessity of maintaining quality of care standards above all (Nania 2006). Measuring the productivity of knowledge workers who work in, or for, government remains notoriously difficult, but almost everyone concedes it is relatively low (Bouckaert 1990) due to the nature of bureaucracies and compulsory monopolies (Haenisch 2012).

In some specific contexts, knowledge worker productivity can be estimated (Iazzolino and Laise 2018) or deduced from efficiency, utilization, or quality measures (Al‐Darrab 2000). Trends in management productivity can also be deduced from changes in the productivity of factory workers or other laborers whose productivity can be more directly assessed (Goldman 1959). Moreover, knowledge worker productivity usually varies strongly and positively with compensation and other incentives (Kaufman 1992). Their productivity is also positively associated with educational level (Rangazas 2002), age (Burtless 2013), and healthy sleep patterns (Nena et al. 2010).

References

Al‐Darrab, Ibrahim A. 2000. “Relationships between Productivity, Efficiency, Utilization, and Quality.” Work Study. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/00438020010318073 .

Alperson-Afil, Nira. 2017. “Spatial Analysis of Fire.” Current Anthropology. https://doi.org/ 10.1086/692721 .

Andersen, Thomas Barnebeck, Peter Sandholt Jensen, and Christian Volmar Skovsgaard. 2016. “The Heavy Plow and the Agricultural Revolution in Medieval Europe.” Journal of Development Economics. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.08.006 .

Baugher, Sherene. 2001. “What Is It? Archaeological Evidence of 19th-Century Agricultural Drainage Systems.” Northeast Historical Archaeology. https://doi.org/ 10.22191/neha/vol31/iss1/4 .

Baumol, William J. 1987. Productivity Growth, Convergence and Welfare: What the Long Run Data Show.

Bergh, Andreas, and Carl Hampus Lyttkens. 2014. “Measuring Institutional Quality in Ancient Athens.” Journal of Institutional Economics. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/s174413741300043x .

Binswanger, Hans. 1986. “AGRICULTURAL MECHANIZATION.” The World Bank Research Observer. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/wbro/1.1.27 .

Black, Stephen L., and Alston V. Thorns. 2014. “Hunter-Gatherer Earth Ovens in the Archaeological Record: Fundamental Concepts.” American Antiquity. https://doi.org/ 10.7183/0002-7316.79.2.204 .

Bó, Ernesto Dal, Pablo Hernández, and Sebastián Mazzuca. 2015. “The Paradox of Civilization: Pre-Institutional Sources of Security and Prosperity.” https://doi.org/ 10.3386/w21829 .

Bouckaert, Geert. 1990. “The History of the Productivity Movement.” Public Productivity & Management Review. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/3380523 .

Bowles, Samuel, and Jung-Kyoo Choi. 2013. “Coevolution of Farming and Private Property during the Early Holocene.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1212149110 .

———. 2019. “The Neolithic Agricultural Revolution and the Origins of Private Property.” Journal of Political Economy. https://doi.org/ 10.1086/701789 .

Boyer, C. B., and U. C. Merzbach. 1993. “A History of Mathematics.” Biometrics. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/2532593 .

Broadberry, S. N. 1994. “Comparative Productivity in British and American Manufacturing during the Nineteenth Century.” Explorations in Economic History. https://doi.org/ 10.1006/exeh.1994.1022 .

Broadberry, Stephen, and Douglas Irwin. 2004. “Labor Productivity in Britain and America During the Nineteenth Century.” https://doi.org/ 10.3386/w10364 .

Brodard, Aurélie, Delphine Lacanette-Puyo, Pierre Guibert, François Lévêque, Albane Burens, and Laurent Carozza. 2016. “A New Process of Reconstructing Archaeological Fires from Their Impact on Sediment: A Coupled Experimental and Numerical Approach Based on the Case Study of Hearths from the Cave of Les Fraux (Dordogne, France).” Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s12520-015-0250-7 .

Burtless, Gary. n.d. “The Impact of Population Aging and Delayed Retirement on Workforce Productivity.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/ 10.2139/ssrn.2275023 .

Castañeda, Nuria. 2016. “A Few Good Blades: An Experimental Test on the Productivity of Blade Cores from the Casa Montero Early Neolithic Flint Mine (Madrid, Spain).” Journal of Lithic Studies. https://doi.org/ 10.2218/jls.v3i2.1435 .

Comin, Diego. 2008. “Total Factor Productivity.” The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. https://doi.org/ 10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_1681-2 .

Cornélio, Alianda M., Ruben E. de Bittencourt-Navarrete, Ricardo de Bittencourt Brum, Claudio M. Queiroz, and Marcos R. Costa. 2016. “Human Brain Expansion during Evolution Is Independent of Fire Control and Cooking.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 0. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fnins.2016.00167 .

Cortada, James. 2009. “Rise of the Knowledge Worker.” https://doi.org/ 10.4324/9780080573014 .

Cosgel, Metin M. n.d. “Agricultural Productivity in the Early Ottoman Empire.” Research in Economic History. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/s0363-3268(06)24005-9 .

Cuomo, Serafina. 2005. “Ancient Mathematics.” https://doi.org/ 10.4324/9780203995730 .

de Becdelièvre, Camille, Camille de Becdelièvre, Tamara Blagojević, Jelena Jovanović, Sofia Stefanović, Zuzana Hofmanová, and Marko Porčić. 2021. “Palaeodemography of the Foraging to Farming Transition: Insights from the Danube Gorges Mesolithic-Neolithic Transformations.” Journey of a Committed Paleodemographer. https://doi.org/ 10.4000/books.pup.54310 .

Drucker, Peter F. 2018. “The New Productivity Challenge.” Quality in Higher Education. https://doi.org/ 10.4324/9781351293563-2 .

Form, William. 1987. “On the Degradation of Skills.” Annual Review of Sociology. https://doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.so.13.080187.000333 .

Form, William, and Larry Hirschhorn. 1985. “Beyond Mechanization: Work and Technology in a Postindustrial Age.” Contemporary Sociology. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/2071327 .

Freeth, Tony, David Higgon, Aris Dacanalis, Lindsay MacDonald, Myrto Georgakopoulou, and Adam Wojcik. 2021. “A Model of the Cosmos in the Ancient Greek Antikythera Mechanism.” Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-021-84310-w .

Gilbreth, Frank Bunker. 1914. Primer of Scientific Management.

Goldman, Alan S. 1959. “Information Flow and Worker Productivity.” Management Science. https://doi.org/ 10.1287/mnsc.5.3.270 .

Graesch, Anthony P., Tianna DiMare, Gregson Schachner, David M. Schaepe, and John (jay) Dallen. 2014. “Thermally Modified Rock: The Experimental Study of ‘Fire-Cracked’ Byproducts of Hot Rock Cooking.” North American Archaeologist. https://doi.org/ 10.2190/na.35.2.c .

Greene, Kevin. 1990. “PERSPECTIVES ON ROMAN TECHNOLOGY.” Oxford Journal of Archaeology. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1468-0092.1990.tb00223.x .

Gunz, Philipp, Fred L. Bookstein, Philipp Mitteroecker, Andrea Stadlmayr, Horst Seidler, and Gerhard W. Weber. 2009. “Early Modern Human Diversity Suggests Subdivided Population Structure and a Complex out-of-Africa Scenario.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0808160106 .

Haenisch, Jerry P. 2012. “Factors Affecting the Productivity of Government Workers.” SAGE Open. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/2158244012441603 .

Iazzolino, Gianpaolo, and Domenico Laise. 2018. “Knowledge Worker Productivity: Is It Really Impossible to Measure It?” Measuring Business Excellence. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/mbe-06-2018-0035 .

Janssen, Marco A., and Marten Scheffer. 2004. “Overexploitation of Renewable Resources by Ancient Societies and the Role of Sunk-Cost Effects.” Ecology and Society. https://doi.org/ 10.5751/es-00620-090106 .

Jones, Erick C., and Christopher A. Chung. 2006. “A Methodology for Measuring Engineering Knowledge Worker Productivity.” Engineering Management Journal. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/10429247.2006.11431682 .

Karr, Landon P. 2015. “Human Use and Reuse of Megafaunal Bones in North America: Bone Fracture, Taphonomy, and Archaeological Interpretation.” Quaternary International. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.quaint.2013.12.017 .

Karr, L. P., and A. K. Outram. 2015. “Bone Degradation and Environment: Understanding, Assessing and Conducting Archaeological Experiments Using Modern Animal Bones.” International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/oa.2275 .

Kaufman, Roger T. 1992. “The Effects of Improshare on Productivity.” ILR Review. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/001979399204500208 .

Kedar, Yafit, Gil Kedar, and Ran Barkai. 2020. “Setting Fire in a Paleolithic Cave: The Influence of Cave Dimensions on Smoke Dispersal.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.102112 .

———. 2022. “The Influence of Smoke Density on Hearth Location and Activity Areas at Lower Paleolithic Lazaret Cave, France.” Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-022-05517-z .

Kotrschal, Alexander, Björn Rogell, Andreas Bundsen, Beatrice Svensson, Susanne Zajitschek, Ioana Brännström, Simone Immler, Alexei A. Maklakov, and Niclas Kolm. 2013. “Artificial Selection on Relative Brain Size in the Guppy Reveals Costs and Benefits of Evolving a Larger Brain.” Current Biology. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2012.11.058 .

Light, Paul C. 2019. “The True Size of Government.” The Government-Industrial Complex. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/oso/9780190851798.003.0002 .

Matranga, Andrea, and Luigi Pascali. 2021. “The Use of Archaeological Data in Economics.” The Handbook of Historical Economics. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/b978-0-12-815874-6.00014-9 .

Motwani, Jaideep, Ashok Kumar, and Michael Novakoski. 1995. “Measuring Construction Productivity: A Practical Approach.” Work Study. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/00438029510103310 .

Nania, Paula G. 2006. “Is Measuring Productivity a Waste of Time?” AORN Journal. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)60122-1 .

O’Brien, Patrick K., Leandro Prados, and De La Escosura. 1992. “Agricultural Productivity and European Industrialization, 1890-1980.” The Economic History Review. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/2598051 .

O’Connor, Sue, Rintaro Ono, and Chris Clarkson. 2011. “Pelagic Fishing at 42,000 Years Before the Present and the Maritime Skills of Modern Humans.” Science. https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1207703 .

Ofek, Haim. 2001. Second Nature: Economic Origins of Human Evolution. Cambridge University Press.

Olmstead, Alan L., and Paul W. Rhode. 2008. “Creating Abundance.” Cambridge Books. https://ideas.repec.org/b/cup/cbooks/9780521673877.html .

Perreault, Charles, P. Jeffrey Brantingham, Steven L. Kuhn, Sarah Wurz, and Xing Gao. 2013. “Measuring the Complexity of Lithic Technology.” Current Anthropology. https://doi.org/10.1086/673264.

Price, Michael. 2021. “Our Earliest Ancestors Weren’t as Brainy as We Thought, Fossil Skulls Suggest.” Science. https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.abi9188 .

Ramírez, Yuri W., and David A. Nembhard. 2004. “Measuring Knowledge Worker Productivity.” Journal of Intellectual Capital. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/14691930410567040 .

Rangazas, P. 2002. “The Quantity and Quality of Schooling and U.S. Labor Productivity Growth (1870–2000).” Review of Economic Dynamics. https://doi.org/ 10.1006/redy.2002.0165 .

Sabel, Charles, and Jonathan Zeitlin. 1985. “HISTORICAL ALTERNATIVES TO MASS PRODUCTION: POLITICS, MARKETS AND TECHNOLOGY IN NINETEENTH CENTURY INDUSTRIALIZATION.” Past and Present. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/past/108.1.133 .

Sanfelice, Domenico, and Piero Andrea Temussi. 2016. “Cold Denaturation as a Tool to Measure Protein Stability.” Biophysical Chemistry. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bpc.2015.05.007 .

Schlanger, Nathan. 1996. “Understanding Levallois: Lithic Technology and Cognitive Archaeology.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/s0959774300001724 .

Semaw, Sileshi, Michael Rogers, and Dietrich Stout. 2009. “The Oldowan-Acheulian Transition: Is There a ‘Developed Oldowan’ Artifact Tradition?” Sourcebook of Paleolithic Transitions. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/978-0-387-76487-0_10 .

Sena, Vania. 2020. “Measuring Productivity.” Productivity Perspectives. https://doi.org/ 10.4337/9781788978804.00008 .

Shackleton, Robert. 2013. Total Factor Productivity Growth in Historical Perspective.

Shantz, Amanda, Kerstin Alfes, and Catherine Truss. 2014. “Alienation from Work: Marxist Ideologies and Twenty-First-Century Practice.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/09585192.2012.667431 .

Tainter, Joseph. 1988. The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge University Press.

Tarlach, Gemma. 2020. “5 Skulls That Shook Up the Story of Human Evolution.” Discover Magazine. May 15, 2020. https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/5-skulls-that-shook-up-the-story-of-human-evolution .

Ville, Simon. 1986. “Total Factor Productivity in the English Shipping Industry: The North-East Coal Trade, 1700-1850.” The Economic History Review. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/2596345 .

Wadley, Lyn. 2013. “Recognizing Complex Cognition through Innovative Technology in Stone Age and Palaeolithic Sites.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/s0959774313000309 .

Weisdorf, Jacob L. 2005. “From Foraging To Farming: Explaining The Neolithic Revolution.” Journal of Economic Surveys. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.0950-0804.2005.00259.x .

Westermann, W. L. 1915. “The Economic Basis of the Decline of Ancient Culture.” The American Historical Review. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/1835540 .

Wilkins, Jayne, Benjamin J. Schoville, Kyle S. Brown, and Michael Chazan. 2012. “Evidence for Early Hafted Hunting Technology.” Science. https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1227608 .

Zieschang, K. 2018. “Productivity Measurement in Sectors with Hard-to-Measure Output.” The Oxford Handbook of Productivity Analysis. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190226718.013.6 .

How the New Deal Subdued Private Charity

N.B. Another belated entry from FreedomFest. Gave a PPT instead of this speech on this one. Would copy the slides but I always found that difficult. So here is some text on the matter, which melds ideas from my forthcoming Liberty Lost (on nonprofits) with my almost finished New Deal ms.

If you think you have it bad today, exactly 90 years ago the U.S. was in the depths of the Depression and there was a progressive Democrat in the Oval Office pushing through a set of radical policies that dramatically and permanently transformed America, largely for the worse. His name was Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) and his policies were collectively called the New Deal.

One of the many awful things to come out of FDR’s New Deal, which was a sort of proto-Great Reset, was the crowding out of private charity. Although private charity in America remains robust compared to other countries, it’s a shell of its former glorious self because of policies implemented by FDR.

Alexis D’Tocqueville famously pointed out that Americans loved to associate together to overcome problems. Other foreign visitors and contemporary legal scholars tracking court cases and precedents were similarly amazed at Americans’ ability to self organize.

Many early voluntary associations were little more than informal clubs but the most significant ones formed corporations, what we today called nonprofits.

The split between for- and nonprofits corporations began in England back in the day but the distinction became clearer in the early national period of the U.S. due to a dispute over the Bank of North America or BNA.

Some people wanted the BNA to provide services to the community instead of just its stockholders and depositors. After an extensive public and legislative debate, it was decided that “moneyed” corporations had no such obligations unless explicitly stipulated in their charters. Nobody would invest in institutions that sought to achieve non-monetary goals or that could be influenced by outside parties, a point proven when a Massachusetts life insurer later found it difficult to secure equity financing when its charter stipulated large payments to a charitable hospital.

People who wanted to pursue broader goals were welcomed, however, to form non-pecuniary corporations to pursue those ends.

And they did.

My forthcoming book, Liberty Lost, puts some concrete numbers on the size of America’s Third Sector. By tracing charters in state statute books, I can say with certainty that the various U.S. states between 1800 and the Civil War allowed the formation of over 15,000 nonprofit corporations, or about 1 per year for every 100,000 Americans.

Additional nonprofits chartered by general acts of incorporation are not included in that figure because they are much more difficult to track but they also likely numbered in the thousands.

Nonprofits included everything from charities, religious and secular, to marching bands and armed militia units. Many nonprofit schools also formed, as did fraternal organizations, scientific institutes, agricultural and medical societies, and abolitionist groups.

Even within the charity category, the range of services voluntarily provided was enormous, and literally cradle to grave, with charities devoted to helping pregnant women, postpartum women, infants and young children, and older children who were orphaned or simply unwanted.

Various nonprofit clinics helped people throughout life deal with health problems, from rotten teeth to abscesses and cancer, and deficiencies of food and fuel. Nonprofit hospitals helped the very sick to die and various fraternals made sure that members received proper burials and that their surviving spouses and children received some monetary aid.

During and after the Civil War, the nonprofit sector grew ever larger and broader. Progressives worked to replace parts of the Third Sector with government institutions, like mental asylums, by arguing for economies of scale and more uniform treatment, at least at the state level. They made some progress nationalizing services traditionally provided by the Third Sector but not until the Great Depression and New Deal was private charity truly assailed.

The New Deal’s overall agenda was to replace individual autonomy and initiative with federal government programs so that FDR would have the patronage leverage necessary to win re-election in 1936, 1940, and 1944.

New Deal critics like Garet Garrett and E.C. Harwood saw the New Deal for what it was, a major step toward state socialism and collectivism but the New Dealers won the battle for hearts and minds, a major theme of my forthcoming book FDR’s Great Reset: The Collectivist Miseries of the New Deal so most Americans were inculcated with the notion that FDR saved America and its economy, especially those worst off, who nobody else could or did help.

In fact, while the recession that began in August 1929 was caused by the business cycle, the subsequent downturn was due to the Federal Reserve’s bungling, that damnable tariff, and high wage policies. The New Deal prolonged the downturn, especially in employment, and squelched the bounce off the March 1933 nadir with unconstitutional power grabs like the NRA and its wretched Blue Eagle.

Iconic pictures of long lines of unemployed men waiting for soup and stale bread were caused, in large part, by the New Deal’s destruction of America’s traditional social safety net, the ability to work for room and board, with minimum wage laws.

Part of the New Deal’s disinformation campaign included bashing America’s Third Sector, especially the charitable component, as ineffective in the face of the greatness of the Depression. In 1938, for example, WPA researchers dug up the fact that Mrs. James John Roosevelt, one of FDR’s ancestors, had asked the New York Common Council to aid unemployed seamstresses in 1851 because QUOTE all assistance from Charitable Societies is withdrawn UNQUOTE.

The withdrawal occurred but the New Deal friendly factoid excluded crucial context: charities stockpiled funds during relatively good years, like 1851, so they would have ample resources for relatively bad years, like 1857. That strategy also helped to mitigate free rider problems because if a worker was unemployed during a depression, it may not have been the worker’s fault but if a worker was unemployed for an extended period in good times, it probably was the worker’s fault for not taking the ubiquitous room and board option.

In part because they had stocked up on assets during the Roaring 20s, nonprofits did a tolerable job during the Depression. Most fraternals continued to pay promised benefits and charities continued to fulfill their missions. New England, which had long since developed the deepest charity network in the nation, held up particularly well.

If that seems incredible, keep in mind that the Depression was pretty sweet if you remained employed, as 3 out of 4 Americans did even at the worst point. Real wages, that is nominal wages adjusted for deflation, were high and assets were dirt cheap. Many could afford to increase their charitable contributions, and did.

The biggest threat to charities was not the Depression, but the New Deal’s large tax increases, which of course fell hardest on those most able to donate to charities. Later, charities were able to fight back by securing tax deductions for charitable contributions but they had already lost much ground to Uncle Sam.

The New Deal did not directly attack charities like it did for-profit corporations but it clearly favored some over others, like FDR’s charity, the Warm Springs Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, which raised much money starting in 1934 thanks to celebrity endorsements from Mickey Rooney, Lucille Ball, and others. Even staunch Republicans like Robert Taylor were forced, by the terms of their Hollywood contracts, to pitch in too.

The misinformation campaign surrounding Social Security was particularly intense. New Dealers noted that 50 percent of the elderly lived in poverty in 1935 without noting that most of those received additional assistance from families, charities, and/or local governments.

The percentage of Americans aged 65 or older who were institutionalized indeed doubled during the Depression, but only from 1.5 to 3 percent, a level lower than that recorded in 1910. The system of private security, which included saving for superannuation via a prudent mix of investment in real estate, insurance, and securities, bent but did not break. The New Deal simply assumed it away, as it did much else in the name of the national “emergency.”

The ramifications of this sea change are still being felt today. Many churches, for example, allowed the government to begin providing relief and in the process reduced demand for their services, pun very much intended. They still passed the hat to fund their own activities but no longer stood as bulwarks against community deterioration as Uncle Sam crowded out an estimated 30 percent of religious charity.

Instead of combatting incursions like Social Security and poor relief, leaders of secular charities also caved to the New Deal. Some even liked the idea of turning over the most costly problems to the federal government so they could concentrate on more niche issues. But of course that led to a decrease in contributions because many donors found their new missions less important.

What everyone seems to have forgotten is that nonprofits are the most democratic means of alleviating social problems. Instead of voting for politicians who then do what they want, which often means aiding their re-election campaigns, individuals vote with their time and dollars in a voluntary system.

The most important and effective charities thrive while the ineffective ones fail due to lack of funds. That induces them to compete with each other for donor dollars instead of currying favors from politicians and bureaucrats, as many do today to secure government grant money. That makes them mere appendages of government instead of independent expressions of the will of donors and the strength of volunteerism, which is exactly what New Dealers wanted.

To regain some liberty, the American people need to not just shrink federal spending, they also need to step into the resulting vacuum with privately funded charities and other nonprofits organizations. And as they did in the 1780s and periodically thereafter, they need to remind people that for-profit corporations thrive only when they are allowed to earn profits and not turned into the unwilling vehicles of government policymakers.

I argue that maintenance of a vigorous system of voluntary association is one of the many unenumerated rights that should be, but currently isn’t, protected by the Ninth Amendment.

But I’ll save that discussion for another time and place.

Thank you!

It's a Trick Question! Who Is More Important, Smith, Marx, or Keynes?

N.B. I started this speech before realizing it was a panel session! Made many of the same arguments in the discussion at FreedomFest Memphis 2023.

Obviously, the question is a trick or trap because the clear winner is Alexander Hamilton.

I realize that might be a dangerous proposition to espouse at a libertarian convention but several other

classical liberal scholars, like Richard Salsman, also have lauded Hamilton’s grasp of economics.

In fact, I learned just yesterday that Salsman has an article on Hamilton as economist forthcoming in

The Independent Review. Interestingly, except on international trade, Salsman makes different points from what I will here today.

The difference between Hamilton’s advocates and critics is that his advocates have actually studied

what Hamilton said and did in its totality and do not simply follow old canards, most of which stem from attempts to leverage Hamilton’s genius for partisan gain.

So please keep an open mind. You can find minute documentation of all of this in several of my books

and articles as well as those of Salsman, financial historians Richard Sylla and David Cowen, and

international trade economist Doug Irwin.

One might protest that Hamilton was not an economist but in fact he was one heck of an economist

and was able, as Treasury Secretary, to test many of his ideas in the real world. He was, in that respect, more of an empirical or scientific economist than most, who were mere scribblers or, worse, professors.

The mature Hamilton, as Treasury Secretary, was not so much a critic of Adam Smith

as he extended some of Smith’s ideas to new realms. Aaron Burr assassinated him before he could

formalize his ideas but nevertheless he made numerous key contributions in the areas of asymmetric

information, particularly moral hazard in bailouts and corporations; international trade, specifically in

what would later be called Harberger Triangles; administrative efficiency; the economics of slavery;

and the limits of sovereign debt.

Hamilton was long gone before Marx or Keynes came along but he sure as heck was no communist

and he debunked the notion that deficit financing could smooth out the business cycle before Keynes

revivified it.

Smith infamously disdained corporations due to their high agency costs. Instead of trying to squelch

corporations in America, Hamilton sought ways to reduce principal-agent problems within corporations

by authoring at least four corporate charters, three for banks and one for a manufacturing company,

with built in checks and balances. They proved incomplete in the case of the manufacturing company

but the problem was corrected and the banks did extremely well.

Three of those charters moved the country towards general incorporation statutes by showing it was

possible to create a joint-stock company, with limited liability and entity shielding, without a formal state

charter. Although adopted slowly, general incorporation helped to ensure that America’s economy

remained open access and entrepreneurial.

Hamilton believed in economic freedom, including the right to form non-profit voluntary associations to

alleviate social issues and what we now call sound money. He was responsible for defining the US

dollar in terms of gold and silver and ensuring that bank notes and deposits were convertible on

demand into specific amounts of precious metals. He also helped to ensure that inconvertible bills of

credit or other forms of fiat money issued by state governments were made unconstitutional.

In terms of the moral hazard involved in bailouts, Hamilton in 1791 and 1792 developed what would

later be called Bagehot’s Rule, which states that the lender of last resort should lend freely at a penalty

rate to all who could post sufficient good collateral. That rule stops panics by protecting solvent

borrowers but denying subsidies to insolvent ones.

Hamilton was an abolitionist, pushing to rid New York of the peculiar institution, which he understood

was profitable for enslavers but ultimately bad for economic growth and development. Had he lived, he

almost surely would have written an analysis like that of Hinton Helper by the mid-1820s.

His views on the national debt and international trade are perhaps the most important to discuss

because they are so often misunderstood.

Unlike Smith, who deprecated all state debts, Hamilton was a debt realist. He held that governments

should borrow to fund wars and other major state functions, like the acquisition of territory. During

peacetime, it should repay its previous borrowings to the extent possible, borrowing on net if

necessary during downturns but simply to fund normal government operations, not to stimulate the

economy. Debt repayment could hurt the economy, so it should not be rapid but rather aided by growth in population and productivity. And any increase should be linked to new taxes to mute the “borrow and

spend” habit that politicians find so alluring.

In short, Hamilton did not believe in a large, permanent national debt as his critics claim by eliding his

correct assertion that the national debt is a blessing QUOTE if it is not excessive UNQUOTE. He even

detailed what he meant by an excessive national debt and I’m chagrined to report that the US national

debt has been excessive by Hamilton’s measure since the great bailouts following the Global Financial

Crisis of 2008.

The national debt helped the economy, he correctly noted, because it helped to create loyalty to the

new government, thus unifying the country and reducing policy uncertainty. It also helped by providing

businesses and banks with a liquid security in which they could safely stash cash. The market for

government bonds helped the development of markets for corporate bonds and equities, which

provided entrepreneurs with external funding options outside of the banking system.

Critics also like to claim that Hamilton implemented a protective tariff though the notion has been

exploded by numerous scholars, including Dartmouth’s Doug Irwin. Hamilton put in place a revenue

tariff carefully geared toward maximizing government revenue by charging a higher rate on luxury

items, like imported liquor. Hamilton infamously taxed domestic whiskey production in part to

discourage domestic liquor production.

Confusion arises because later protectionists used and abused Hamilton’s Report on Manufacturers to

claim that Hamilton was a protectionist. He was not. His Report was didactic, explaining the options

open to Congress. So he discussed rather than espoused so-called infant industries. In his discussion

of the relative costs and benefits of protective tariffs and bounties, he clearly noted that tariffs created

two deadweight loss triangles while bounties created only one, which is what international trade

textbooks still argue.

Hamilton understood that taxes of all types should be minimized because of the distortions and tax

wedges they cause. But the national debt had to be serviced and paid down. Hamilton preferred

revenue tariffs over other types of taxes because they were relatively easy to collect at ports of entry

and were embedded in prices.

As the federal government learned twice in the 1790s, internal taxes threatened liberty and

insurrection but they had to be established lest tariffs failed to produce the needful during war or

economic downturn. Tariffs indeed served as the government’s largest peacetime revenue stream, with

excise taxes like the whisky excise a close second, until implementation of the income tax in the 20th

century.

In sum, Hamilton extended Adam Smith to the real world of policy and passed with flying colors. The

other two guys aren’t even close as Marx wanted to enslave all to the state and Keynes wanted to

deficit finance to smooth business cycles and to a large extent has gotten us into the excessive debt

mess we are currently in.

August 7, 2023

US Debt Closer to Junk

Sirs,

I channel through policy historian Robert E. Wright from the Great Beyond to warn that the recent debt downgrades by Mr. Fitch is much too sanguine. America’s debt today should be rated closer to junk than to top notch. The situation is not quite as dire as when I accepted General Washington’s request to serve as the nation’s first Treasury Secretary, but reforms akin to those that I implemented in the early 1790s must be made lest the nation’s public credit be impaired further.

A dozen years ago, Mr. Poor also downgraded the nation’s public securities a notch, leaving only Mr. Moody to assure the public that nothing is amiss. All of the Big Three credit rating agencies, it must be observed, inflate the scores of all but the most pathetic securities lest they face challenge. Given the power of the executive branch of the national government to tax, regulate, and otherwise control private entities and persons, rest assured that Messrs. Poor, Moody, and Fitch tremble at the notion of making public their true views of America’s current creditworthiness.

In my time, the prices of public debt obligations served as a reliable guide of creditworthiness. I watched proudly as my fiscal policies, though the subject of partisan controversy, steadily raised the price of public obligations from a few pennies on the dollar to above par. American economic independence from Britain was definitively achieved when the yields on its bonds dipped below those of the Mother Country, in Britain’s own markets no less.

Bond prices then were internationally comparable because stated essentially in gold or silver. Today, with the globe awash in bills of credit (“fiat money” as currently fashioned), they convey less information about creditworthiness and more about relative inflation expectations and the ability of some nations, like the United States, to force debt on their own citizens and on other governments. Creditworthiness is thus more subjective today, but still amenable to analysis.

I once stated that America’s national debt would be a blessing and a cement to the Union and it long proved a net benefit. The government’s ability to borrow large sums relatively quickly and cheaply saved the country from recolonization in the 1810s, being ripped into two by a massive insurrection in the 1860s, and being dominated by evil foreign powers in the 1940s. Yet despite those exertions it remained so easily manageable that it was completely paid off in the 1830s and could have been again in the 1910s if a great war had not interceded.

In the same breath that I extolled the virtues of public credit, however, I warned that the national debt could become excessive and hence a net burden. It became excessive following the government’s unwarranted bailout during the Global Panic of 2008, which triggered the downgrade by Mr. Poor. The Great Pandemic of 2020 occasioned another burst of unwarranted borrowing and the capitulation of Mr. Fitch.

I say unwarranted because both episodes broke rules that I laid down as Treasury Secretary and that were followed even by my Virginian political rivals. Firstly, during panics government money should be employed to make loans only to private parties willing to pay a penalty rate and able to post sufficient collateral. Due to my untimely death, this rule has come to be associated with one Mr. Bagehot. Whatever the attribution, adherence to the rule stymies panics by assuring solvent businesses that they can obtain gold if necessary while not subsidizing insolvent concerns. The technique of flooding the market with bills of credit and lending capital to commercial enterprises encourages nothing but profligacy in private business and extravagance with the public purse.

Secondly, the Treasury should never borrow money to stimulate the economy or to transfer resources from one citizen to another, or from the citizens of this nation to those of another. It should borrow only for emergencies, like just wars, and when tax receipts prove insufficient to service the debt during an unexpected downturn in trade.

Although I sought to establish a national government larger and more vigorous than the one sought by my political rivals, even I am appalled by its current size and scope and am amazed that the legislative and judicial branches have allowed the executive to gain control of the public purse. America must restore its balance through legislation and court decisions before the republic is lost to an oligopoly of placemen and sycophants.

Thirdly, governments should never borrow money without also raising a tax sufficient to service and retire the resulting debt. In addition to putting creditors at their ease, such a policy minimizes the incentive of politicians to borrow and spend, which creates the illusion that they have provided some benefit without a cost.

Until America follows its unwritten fiscal constitution and grows out of its current debt burden, Treasury’s debt will remain closer to the junk status of the 1780s than to the AAA status my policies elevated it to in the 1790s, regardless of the letters assigned to it by the likes of Messrs. Fitch, Poor, and Moody.

Mr. Hamilton chose to channel through Robert E. Wright, a senior faculty fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research, because of his authorship of One Nation Under Debt: Hamilton, Jefferson, and the History of What We Owe (2018).

March 31, 2023

Joe B

[Sing to the tune of Dolly Parton's "Jolene")

Joe B, Joe B, Joe B, Joe B

I’m begging of you please don’t take our liberty

Joe B, Joe B, Joe B, Joe B

Please don’t take it just because you control our country

Your cunning is beyond compare

With nasty patches of snowy hair

With Tom Cruise sunglasses your eyes hidden

Your smile is like the breath of the Grinch

Your voice is hard like a thunderstorm

And we cannot compete with your F-16s

Joe B

At major public events you do sleep

And there is nothing I can do to keep

From crying when Twitter bots defend your name

Joe B

And I can easily foresee

How easily you can take our liberty

But you don’t know what it means to everybody

Joe B

Joe B, Joe B, Joe B, Joe B

I’m begging of you please don’t take our liberty

Joe B, Joe B, Joe B, Joe B

Please don’t take it just because you can

You could have your choice of trans-men

But we can never have liberty again

It’s the only thing for us

Joe B

I had to write this song for you

Our life, liberty, and happiness depends on you

And whatever you decide to do

Joe B

Joe B, Joe B, Joe B, Joe B

I’m begging of you please don’t take our liberty

Joe B, Joe B, Joe B, Joe B

Please don’t take it even though you can

Joe B, Joe B

January 21, 2023

California's Reparations Conundrum

The state of California and some of its municipal subdivisions currently contemplate paying reparations to their Black residents. This reparations measure is not for chattel slavery per se, as slavery was historically illegal in California dating to its admission to the union in 1850. Rather, it is a supposed recompense for creating slavery-like conditions that activists ascribe to under-elaborated injustices of California’s past. It is reparations for repression, in other words.

The sums being discussed, $5 million per person in the case of San Fran and half a million per person by the state’s reparations task force, are as budget-busting as they are eye-popping. The state’s estimate alone comes out to $500 billion if only 1 million of California’s 2.25 million Black residents are found eligible.

For the sake of argument, let’s stipulate that the repression claims are true and the sums suggested are just. Let’s also stipulate that California can fairly discern eligibility reasonably well at reasonable cost. That still leaves the huge question of who should pay the big bill?

Certainly not current taxpayers, who had no control over the racial injustices of California’s past. Moreover, because cash is fungible, any federal grants to California and its guilty subdivisions would risk exposing the taxpayers of other states to a liability for any reparations program. As a practical matter, California’s proposed reparations scheme could not be implemented without unfairly confiscating tax dollars from potentially tens of millions of people who played no part in the state’s alleged wrongs.

But it is also not clear that current California taxpayers should have to pay for reparations either, through any combination of increased taxation or decreased government services. They did not create the repressive laws and policies and many opposed them, to no avail.

Besides, two wrongs do not make a right. Who’s to say that in a generation California taxpayers won’t legitimately claim to have suffered repression by being forced to pay for sins they did not commit? Moreover, given California’s admission of its own guilt in the enacting of a reparations program, who could trust it to administer such a large transfer of wealth?

That leaves three sources of funds: the guilty governments themselves, the political parties in power, and the politicians and bureaucrats who voted for and oversaw the harmful laws, and the judges who failed to overturn them.

Forget the third option as individual policymakers are well shielded legally. Individuals could also claim that they were just following orders from their parties or their bosses, which holds up better in civil than criminal cases.

If political parties were held solely accountable, they would have to claim bankruptcy and fold because donors would disappear and they would not have sufficient assets to cover the costs. So score one for making the political parties culpable.

If the state government itself is to pay, it does own assets like roads, parks, buildings, and the like, that could be sold to the highest bidders. Unfortunately, though, California’s most recent estimate of its capital assets (p. 44 of its 2020 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report) reports a mere $137 billion.

Perhaps if culpable cities pitched in all their assets, too, enough could be raised but California and its major municipalities all have other creditors whose interests would obviously be adversely impacted by such a drastic move. And, again, two wrongs don’t make a right.

The only real remedy, it seems, is to declare California a failed state, make it a territory, and allow it, or parts of it, back into the Union after it ratifies a constitution that ensures its people a republican form of government, incapable, by design, of ever inflicting such damage on anyone ever again.

December 30, 2022

SD Needs Real Reform, Not Con D Virtue Signaling

A rational, Christian response to a mugging is to aid the victim while ensuring the perpetrator never repeats the crime. South Dakotans know this, which, along with Constitutional Carry, is why crime hasn’t spiked here as in so many other places across the nation. A small majority of South Dakotans, however, have voted to change the state constitution to join California and New York and allow medical mugging to continue.

I gather that supporters of Constitutional Amendment D (CAD) voted to help poor people with big medical bills, and use other Americans’ money to do it. What a deal! But Medicaid expansion really does not help the poor any more than reimbursing a mugging victim does, especially when the mugger goes unpunished, poised to strike again. It’s virtue signaling at best and at worst a capitulation to Big Sick Care.

Medicaid expansion under CAD will aid healthcare providers (HCPs), i.e., the perpetrators of the problem, the very institutions that pushed hard for expansion. Yes, HCPs should earn enough to induce them to provide healthcare services, which everyone needs to some extent or another. But do not forget that HCPs already get what a competitive market would pay them and a whole lot more besides. For a full explanation and proof, see Sean Masaki Flynn’s 2019 book, The Cure That Works.

Flynn points out that US healthcare, and unfortunately South Dakota’s too (after showing some promise before implementation of Obamacare), is much too expensive. There are no real prices, just negotiated settlements with insurers or governments. And the fee-for-service model creates a panoply of perverse incentives, including a predilection to treat symptoms but not to cure the underlying causes of illness. It’s more sick care than healthcare.

Early in 2022, my adult son was hospitalized in Sioux Falls for several days. The HCPs thankfully did not kill him, but they did not fix him either. He is still getting bills for services that may or may not have been rendered. (He is no doctor and barely remembers his emergency stay.) He was then earning a little too much to receive Medicaid yet his total cost was in the thousands. Under CAD, Medicaid would have chipped in for him but somebody else earning just over 138 percent of the federal poverty line would be in the same situation as my son, facing huge bills for “services” that may only serve the HCPs.

If South Dakotans really want to help the poor, and everyone else, with their medical bills they should compel HCPs to compete on the quality-adjusted price of their services. Then people can shop around for the best deal instead of committing themselves to pay big, convoluted, unknown bills, often for little or nothing in return.

Yes, such a radically commonsensical policy would run afoul of current federal regulations but some cities and states routinely declare themselves “sanctuaries” where federal laws do not apply. South Dakota has a long history of bucking widespread strictures on divorce, interest rate caps, residency rules, trust funds, and the like. Why not burnish that reputation for policy innovation by offering the country an example of a competitive healthcare system that, as Flynn shows, will be much cheaper and better than the one currently mandated from Washington, DC?

December 26, 2022

A Universal Basic Christmas?

By age 4 or 5, I loathed Santa Claus because I noticed that he gave more and better toys to my poorly behaved rich playmates than to me or my little brother even though his production (slave labor?) and transportation costs (lichen for his reindeer) were de minimis and subsidized with literally tons of milk and cookies. Not long after, upon hearing Cheech and Chong’s already classic 1971 bit “Santa Claus and His Old Lady,” I unearthed the conspiracy behind the silly jolly old elf stories. Christmas gifts weren’t magical manna, they were part redistribution scheme, part potlatch, and part savings ploy. At least the consumerist vision of Christmas was, and remains, voluntary.

But now circulating is another implausible legend about economically free gifts, Universal Basic Income or UBI for short. This new legend means Christmas cash for everyone, in equal measure. (It is usually assumed to come once a month, but it could come just on Christmas, or be conceived of as a Christmas present paid in monthly installments.)

I fear that Americans are being subtly conditioned into accepting UBI through repetition of lies and half truths. As I have noted elsewhere, many in the media now label any old welfare program a “UBI pilot” and then tout how it helps its recipients, as if it were not already bloody obvious that extra cash always helps people. The stories, like this one from ABC News in San Francisco, also typically claim that recipients spend all their newfound wealth on “necessities,” as if cash isn’t fungible. The reporters are either morons, or think that their readers are.

While images of poor children having extra socks and other necessities under the Christmas tree may warm your heart as much as it does their feet, adults and even precocious children know that those resources came from somewhere. When the source is voluntary charitable donations, the real spirit of Christmas is fulfilled.

Under a real national UBI, however, the transfers become involuntary. As Aleksandra Przegalinska and I explain in Debating Universal Basic Income (Palgrave 2022), while everyone receives equal UBI payments, the money has to come from somewhere, and in most proposals that somewhere is the middle and upper classes, who end up paying more in taxes than they get from the UBI program.

Exceptions arise only when a government is blessed with something akin to magical manna, like the oil royalties that Alaska and Iran use to fund their respective UBI programs. Few governments have access to such cash cows but there is one great untapped source of revenue available to all governments – increased government efficiency.

If the U.S. government, for example, were to end its massive subsidies for the health and higher education sectors, return to systems of private instead of social security, and scale back its bloated administrative state, it could implement a UBI worth 15 percent of GDP without raising taxes any further.

Ironically, if Uncle Sam were to bestow such a Christmas present upon the American people, instead of presenting them with more inflation and debt like Congres just did, it would unleash so much economic growth that a UBI would no longer be seen as necessary. But this frigid Christmas, most Americans would settle instead for a giant lump of coal.

December 24, 2022

"UBI Pilot" Is Another False Frame

America’s airwaves, blogs, and podcasts are awash with praise for, and criticism of, so-called “UBI pilots.” The problem is that none of the pilot programs, which multiplied like bunnies after the Covid scare began to subside a year ago, can rightly purport to inform the debate over the likely costs and benefits of the universal basic income policy (UBI) currently pushed by proponents in the US and around the globe. Journalistic misrepresentation, whether due to economic illiteracy or incentives to promote Woke causes, threaten to pollute the policy debate over real UBI proposals.

Journalistic misrepresentation of economic policies is not entirely new but has become more prevalent in the 21st century due to declining educational standards and perverse incentives. For example, Wilma Soss (1900-1986) in Columbia University’s journalism school in the early 1920s received a solid grounding in economic and political history and theory that allowed her to forecast changes in the macroeconomy and to provide solid investment advice to millions for a quarter century (1957-1980). Her educational preparation stands in strong contrast to the weak, ideological fare spoon fed to most journalist students in the early Third Millennium AD, especially in economic matters.

Soss faced a better set of incentives, too. Her employer, NBC, did not force her to accept corporate sponsorships, which allowed her to build audience loyalty through trust. Listeners did not always agree with what Soss said on her weekly “Pocketbook News” show, but they knew that she only said what she believed. Today, by contrast, most corporate journalists have incentives to write frothy clickbait or regurgitate partisan talking points.

Soss knew, and experts today agree, that most income transfer programs are not UBI because they are not universal in the sense of being paid to everyone. San Francisco, for example, rightly calls its $1,200 monthly stipend Guaranteed Income for Transgender People, or G.I.F.T. for short, because it’s just a welfare program for low income transgenders.

Conflating UBI with welfare causes two confusions that muddle policy discussions. On the one hand, the conflation increases opposition to actual UBI proposals on false grounds. A truly universal transfer program not limited by need (or subject to gender or other tests), for example, would not necessarily entail the creation and funding of yet another huge government bureaucracy.

On the other hand, UBI “pilots,” even the few that are not means tested, provide false support for a national UBI because they are miniscule in scale, of limited duration, and funded by manna from heavenly donors. Analyses of their outcomes invariably focus on that which is seen, which is people who are better off because they have higher incomes. But that misses that a permanent largescale UBI would have to be involuntarily funded by someone.

Pilots cannot tell us how net UBI payers, those whose taxes increase more than their respective monthly stipends, would react to UBI politically or economically. They are also too short to tell us what will happen to education, employment, or birth rates. Pilot participants tend to stay employed and in school because they know the extra cash flow will soon cease but they might drop out if they believed the money was permanent.

Some pilot principal investigators have analyzed results as rigorously as the current state of social scientific inquiry allows. Others, though, clearly seek to score ideological points by claiming that recipients spend every extra dime on education and clean water. Opponents claim that the extra money just fuels alcohol, drug, and gambling addictions. In fact, money is fungible so the focus should be on how consumption patterns change as incomes increase, but economists do not need transfer pilots to study that.

Ultimately, one’s stance on UBI should not come down to the purported results of pilots, most of which come nowhere close to testing the policy that UBI proponents push. Instead, it should come down to one’s values. Should public policies support individual liberty or government collectivism? If the former, urge the government to bolster voluntary transfer programs. If the latter, why not skip UBI and go right to socialism, the results of which are well documented from long experience at scale?

October 27, 2022

Positive Quarterly Real GDP During Recessions

Three months ago, many scholars, including myself, argued that two consecutive quarters of shrinking inflation-adjusted GDP met the government’s technical definition of recession. A third negative number would have sealed the deal for sure but the estimate for the third quarter, which is weak but positive, muddies matters.

A recent study shows that the U.S., U.K., and Swedish governments produce overly optimistic GDP growth estimates in election years. Even if the numbers are not subsequently revised downwards, the slight growth should not be interpreted to mean that the American economy is in the clear. Housing prices are plummeting while core inflation remains high enough to make further interest rate hikes likely. Real wages continue to lag and most businesses warn of impending layoffs or hiring freezes.

So only something of an economic miracle will prevent the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) from declaring a recession during the Biden administration. A look at the history of its semi-official pronouncements suggests that a quarter of GDP growth will not prevent it from calling the start at the beginning of 2022. In fact, the longest NBER-defined recessions since World War II had one quarter of positive growth embedded in them.

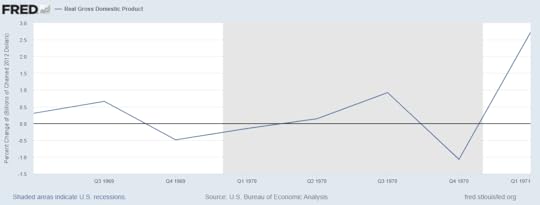

See how the blue line (real GDP) goes above the black line (zero) in the grayed area (NBER recession) during the 1949 recession in the official St. Louis Federal Reserve chart of percent change in real GDP below?

That is not unusual. It happened again in the 1960 recession:

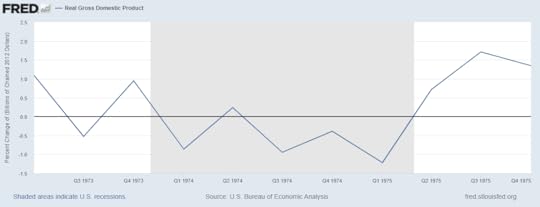

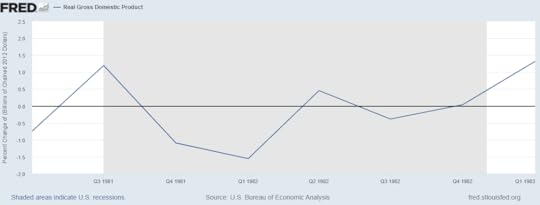

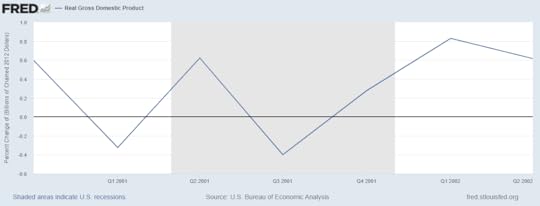

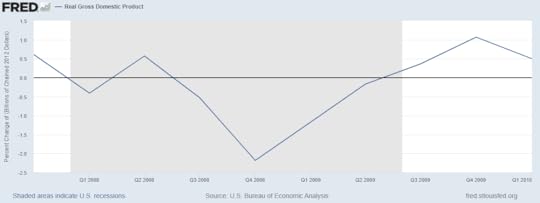

And again in 1970, 1974, 1982, 2001, and 2008, i.e., in all of the nation’s longest postwar recessions:

So don’t let a positive GDP number fool you into thinking the US economy isn’t in a recession. Some call a positive quarterly reading during a recession a dead cat bounce, others a double dip. What you call it doesn’t matter: the only economic thing “strong as hell” right now, besides double dip ice cream sales in the vicinity of POTUS, is fear itself.