Patricia C. Wrede's Blog, page 43

December 22, 2013

Introductory Information

First off, an announcement: we are going to take another run at the New Improved Updated Blog and Website Format, starting tomorrow. I think we have the majority of bugs worked out this time, but if anybody spots anything, please email me.

One of the other big problems with openings (besides hooks, which I talked a bit about last time) is giving the reader enough information to “get” what is going on. It’s an obvious problem for a lot of fantasy and SF, but it actually can affect pretty much any type of novel you want to name. Every book that’s set in a location likely to be unfamiliar to many or most of its readers (whether that location is northern Canada or downtown Beijing) will have a lot of important setting details to get out on the table. Even if the setting is relatively well-known – present day New York City, for instance – there will still be plenty of readers who have never been there, and who aren’t going to know key plot-important details about the setting.

And that’s just the setting stuff. In most novels, the characters have a lot of pre-existing relationships and/or backstory that are vital to understanding the plot. There are details of culture and custom, technicalities relating to particular occupations, specifics of recent local history (imaginary or real) that the writer knows are Important-with-a-capital-I.

By the time they have finished a book, writers have a firm grasp of the Big Picture, as it relates to the story they’re telling. It is sometimes very difficult to back off enough to realize that the reader doesn’t need to know all of that before they start the story.

What the reader needs to know on Page One is: just enough to have a reasonable understanding of what is going on on Page One…and no more.

But, says the writer, on Page One, Angela and Murgatroyd are having a huge argument, and it won’t make sense if the reader doesn’t know they are half-siblings with a long history of antagonism due to the way Angela’s father favored Murgatroyd because he was trying to make up for divorcing Murgatroyd’s mother.

And no, the reader won’t know all that background on his/her first run through the book. But they don’t actually need to know it in order to understand that Angela and Murgatroyd are having a huge row, which is the only thing that’s really important on Page One. Depending on the characters and viewpoint, the argument may very well be an opportunity to slip some of that information in, or it may only be possible to hint at future revelations. There are even a few authors who can break the argument in the middle for a two-page summary of these two characters’ back history, and make it work.

What rarely, if ever, works is starting with the argument and then breaking away for a complete history of the family, including all of the parents, aunts, uncles, siblings, step-siblings, Murgatroyd’s mother’s new husband and his relationship with Murgatroyd, and Angela’s crush on Murgatroyd’s step-brother. What really doesn’t work is dumping all that family history plus a summary of everyone’s relationships with their bosses, teachers, and the city mayor, along with the history of how all these love affairs and feuds came to be, even if the writer knows that all that stuff is going to be vitally important later.

The key word there is later. Yes, the reader will need to know it, but they don’t need it now, on Page One. (Or two or three or five, which is probably what it would take to give a coherent summary of all that stuff.) What they need to know on Page One is: Angela and Murgatroyd are having a huge fight about some topic. They’re related. Murgatroyd is the viewpoint character. They’re in the middle of the city park, at lunch hour, and they’re making enough fuss for people around them to react. Since it’s the opening of the story, a few hints about what Angela and Murgatroyd look like would be welcome before the scene ends.

That’s probably enough for the reader to understand what is happening in this scene. The dialog, stage business, and physical descriptions of the place and the people are almost certainly going to give the writer plenty of opportunity to get all that in without stopping for a long summary of backstory, even if the city park is in a domed space station in 2517.

There is a tendency for people, whether readers or writers, to think that if they know something that adds to the interest or impact of a scene, then that knowledge is necessary before anyone can understand the scene. But while it is true that knowing more about Angela and Murgatroyd’s preexisting relationship adds deeper layers to their opening fight, that knowledge is not actually necessary for the reader to understand what is going on. It adds to the scene, but the reader will do just fine without it.

Readers are fairly willing to wait for explanations, especially at the start of a book. The bigger and more important the mystery/explanation, the longer they are willing to wait for the payoff. Unnecessary minor details can easily clutter up a scene and slow it down, which is not something most writers want to do in the opening scene of their book. Also, cramming all that background information into the first scene means that a lot of readers will start skimming and/or forget the crucial bits and then get puzzled and annoyed when they get to a scene where they do need to know this stuff.

This is one of the reasons why some writers routinely resort to scaffolding. They write a Chapter One or a Prologue that includes all of that “necessary” information, so they don’t have to worry about readers not getting it. And when the book is finished, they chop off that chapter or prologue, and renumber the following chapters, because really, the only reason it was there was because the writer was feeling insecure about his/her ability to get all that hugely important background information across to the reader in a timely and coherent fashion, not because the reader actually needed it right then and there.

If a particular bit of backstory or information fits nicely into a scene – any scene, but especially the first one – then by all means put it in. If something needs to be planted or foreshadowed for later use, ditto (though the very first scene of a novel is not usually the most effective place to be doing either of these things). Any time you find yourself thinking, “Hmm, have I got too much/enough information in this scene?” the answer is probably yes. The one exception I can think of are the writers who habitually and chronically underwrite, but they are rare and seldom, if ever, have a problem with cramming too much into Scene One.

December 18, 2013

Hooks again

Ok, shameless promotional stuff first. The hardcopy paperback version of Wrede on Writing is now available, and as a promotion, the Goodreads site is doing a giveaway – five people, selected at random from those who register, will each get a free copy. For anyone interested the link is here: https://www.goodreads.com/giveaway/show/75614-wrede-on-writing-tips-hints-and-opinions-on-writing

On to the post, which is about hooks.

I come from a family of fishermen. Not the sort of truly serious anglers who spend weeks scouting out the best trout streams to vacation near, but not the sort that go out one weekend a year with a worm on a bent pin, either. And as soon as I was deemed old enough to handle sharp objects safely, I was taught that there are different kinds of hooks, and which one you use depends on where you are fishing and what type of fish you are hoping to catch. You also learn that hooking the fish isn’t enough; you have to set the hook, or the fish is likely to get away before you can reel it in.

This applies as much to writing as to fishing. Depending on who you talk to, the “hook” is the first scene, first page, first paragraph, or first sentence of the story. I tend to vote for the slightly longer versions, but that may be a function of my inability to stop reading something, even the print on cereal boxes, until I get to some sort of finish (like the end of a page or paragraph). I cannot recall ever having read only the first sentence of a story and then skipping the rest of it.

So I am not going to talk about writing catchy first sentences. I’m talking about the rest of that first paragraph, page, and chapter.

The first thing you learn, if you fish, is that you need bait and/or a lure. A bare hook doesn’t catch many fish. In writing terms, this means that, very early in the story, you are dangling something interesting in front of the reader: an intriguing puzzle, an interesting character or situation, a problem in need of solution. It doesn’t have to be the problem, the one that’s the center of the story, but it usually needs to be something more interesting than “Darn, I have a headache and I’m out of aspirin.”

So when you’re looking at your first page, scene, and chapter, the things to ask are “What is the intriguingly unique thing about this place, these people, this situation?” and/or “What questions are raised that the reader is going to want answered?”

This is what makes opening with the hero in mid-fight, madly swinging his sword or shooting at someone, not such a great opening for most books, most of the time, despite all the advice to the contrary. The obvious questions this sort of scene raises are “Why is he fighting these people?” and “Will he survive?” – and readers who’ve read the back blurb and know he’s the hero are pretty sure the answer to the second one is “yes.” That leaves only the “Why” question, which can be intriguing if it’s handled right…but if the main character is so busy lopping off heads that he/she can’t think, it’s pretty tough to look at “why” until after the fight, which leaves the author with a relatively weak hook.

The mid-fight opening hook will work fine on the sort of reader who just wants to read about cool fighting stuff (assuming, of course, that the opening fight displays a bit of coolness). It works best, though, if the fight is unusual in some fairly obvious way, because this raises all sorts of additional questions to pull the reader in.

Opening a story with the librarian at the Mage’s Academy in a life-or-death fight with a set of books, for instance, is interesting to more people than the “standard” shoot-him-or-lop-hi-head-off fight because librarians are not usually people we think of as needing to fight to the death as part of their jobs, books are not usually the sort of opponents featured in this sort of scene, and libraries are not usually the sort of place where this kind of fight takes place. So the reader wants to know, on some level, “Is this a normal event for magical librarians, or is this unusual even here? How do you fight books? What set these books off?” and most importantly, “What else is interestingly different about this person and this place?”

The most effective hooks work on both levels: First, they demonstrate to the reader that this story is going to have cool fighting or cool tea parties or a cool murder-mystery or cool technology; in other words, they let the reader know that the story will deliver whatever the reader expects from this sort of book. And second, they give the reader a sample of the really cool thing(s) that are unique and interesting about this particular story, whether that’s something about the characters, the setting, the situation, the event, etc.

“Giving the reader a sample” does not necessarily mean spilling the beans about the protagonist’s angsty backstory or the cool plot twist on page one – but it may mean showing that she has skills (or problems) that one wouldn’t normally expect from a young legal intern in Chicago, 2013, or demonstrating that even minor things in this story won’t go the way the reader expects. The questions the writer is likely to find useful are “What is the thing that makes this teacher/city street/murder victim/cocktail party/train ride/wedding different from all the lawyers/city streets/etc. that the reader is most likely expecting to see?” and “How do I let the reader know that ASAP?”

The perceptive blog reader will have already noticed that it is all but impossible to do all that in a single sentence. Hence my emphasis on the first paragraph, page, scene, and chapter.

December 15, 2013

Wrong Reasons

Once upon a time, long before I was ever published, I was talking with a friend about things we’d like to do someday, and I confessed that I wanted to write a novel, and even showed him a few chapters. The friend allowed as how he wanted to write a novel, too (which seemed odd, as he read maybe one novel per year, if that, but OK, maybe he was one of those people who can’t admit to liking fiction in public).

About a week later, said friend showed up proudly with three single-spaced pages that he said were the opening of his mystery novel, which our conversation had inspired him to begin. I gave him suitably envious congratulations and asked to see the rest of it when or as he got it written.

I never saw another word.

A year or so later, I met another gentleman who, on hearing that my novel was out under submission, said rather sadly that he, too, should be a writer – all his friends said so. Even his mother said so, ever since he wrote a couple of humorous bits for his high school literary magazine. And he had this great idea for a story.

By then I was a little wiser, and I told him that if he wanted to write it, then he should. He went off, much encouraged, and came back a few days later with quite a reasonable draft of a first chapter.

I’ve never seen another word of that one, either.

I was thinking about these two people from thirty-plus years ago, because I was recently reading an article urging everyone to support people who want to write. Apparently all anyone needs to write a brilliant novel is a little encouragement from their friends.

Supporting would-be writers, though, is not really about cheerleading. It’s about giving the writer what he or she needs, and different people have different needs. My first friend, I now realize, was simply proving to himself that whatever I did, he could do, too. That was enough to carry him through three opening pages, but no farther…and telling him “This is a great story; you should finish it” did not provide him with any motivation to actually sit down and write, because he did not want to write. He wanted to prove something, and telling him that what he’d written was good was enough proof as far as he was concerned. (Also, as long as he’d written a good three-page opening, he didn’t have to go any farther and take the chance that his middle would perhaps not be quite as good.)

In some cases, saying “I think you’d be a great writer” or “I love that story idea; you should write it” are welcomed encouragement; in the case of my second friend, they were perceived as pressure. He, too, didn’t really want to write; what he wanted was to make his friends, his family, and his mother proud and happy by doing something they all said he would be good at and should do. He’d have been happier pursuing the music career that he loved but that none of them were interested in encouraging him to do.

There are, however, plenty of would-be writers who can use a bit of support. The real question is: What kind? Some people are good with a little cheerleading; others automatically discount it as mere social politeness. What they need is something more concrete in the way of support. This could be anything from sending a daily “Have you written your page today?” e-mail to taking the writer out for a weekly or monthly dinner-and-venting session to offering to proofread chapters or put together a research reading list on the habits of elephants.

The way you find out what kind of support a particular writer would find useful is, you ask them. I have one good writer friend who absolutely positively never ever ever wants to be asked “How is the book coming?” or “How’s the writing going?” I have another friend who wants to be asked “So, what chapter are you on now?” every single time we meet. I know this because I asked; the first one feels pressured by even small references to her work; the second one is energized by the interest (and feels pressured, but in a good way).

And some people will never find any encouragement or support to be useful, because they don’t really want to write. They want something else: to please friends, to prove something, to show off, to “be a writer.” Fundamentally, they don’t need encouragement; they need better reasons.

And reasons have to come from inside you.

December 11, 2013

Series Considerations

So I’m sitting here trying to think of a blog post for today, and I get an email from a woman who is preparing to sit down and write her first novel, but she has questions. I read a little farther, and it turns out that she’s thinking ahead. Far, far ahead. She’s not just planning to write a trilogy or an open-ended series; she has a five book series planned out, and then a six-to-eight book set of prequels focusing on different important characters. And she is naturally worried about how to market an eleven-to-thirteen book series, not to mention wondering which of the stories she should start with.

This is far from the first time I’ve run into someone with this sort of problem, and the first question I always ask is, how much of it do you already have written?

If the answer is “None; I wanted to know about the marketing part first,” the would-be author generally has some considerable misconceptions about how publishing works…not to mention how difficult the writing part is going to be. They are usually thinking too far ahead…or rather, they’re counting on needing to think like that. Most multi-book series — interlocking trilogies, trilogy plus spin-offs, main book plus prequels/sequels/spin-offs — got to be what they are because the initial offering (whatever it was) sold really well. Planning a three or six or twelve-book series is all very well, but if the sales aren’t there, you aren’t likely to get an editor to buy more than the first book or two, no matter what your plans are. Publishing is full of horror stories about experienced authors who started something like this and had it canceled out from under them because the sales didn’t live up to the publisher’s expectations; this is even more true of first-timers.

Authors who have actually written most of a book or six have different problems.

About half the time, these authors don’t have a good feel for what their actual story is, or don’t know how to stay focused on it. They keep getting distracted by the cool background for Character A that they had to make up to explain that incident in Chapter Seven, or the neat subplot that is just so interesting and keeps expanding and maybe should be its own book. The other half the time, the authors have Tolkien’s Disease (aka Worldbuilding Syndrome), and they’re totally sure that their many pages of notes and history and previous tales and background and culture are going to fascinate just as many people as his did. Or they’ve fallen madly in love with their character(s) and can’t bear to write about anyone else.

The thing is, if you want to write a trilogy or a series, you have to have enough story to fill it. Not enough world; not enough characters; not enough background or history. Enough story. (You need the other things, too, but a lot of would-be writers fill their book with them, instead of with a story. And then they wonder why editors won’t buy their work … )

There aren’t actually a whole lot of stories that need 900 or more pages to tell them. Even if the author is trying to tell a detailed life-history of their highly-adventurous main character, there are generally shorter stories within it that add up to the person’s whole-life. And making each book a key episode allows for a lot more flexibility than beginning at the character’s birth and moving on until they die.

The other problem is that there really aren’t that many Tolkiens out there, and by that I mean authors who are perfectly happy tinkering with the same characters and world and worldbuilding for forty years. People grow and change and learn; the things they are interested in expand and alter. The world and the characters that are absolutely fascinating right now may not look nearly so interesting in five or six years, when you’re only half done with your planned interlocking story. This leaves the author with the choice of abandoning their work half-finished (which is not really fair to their readers), forcing themselves to write something they find more and more boring and/or stifling, or desperately trying to twist the world/plot/series into some new and more interesting shape (often by writing the sort of spin-offs my correspondent was already planning before she’d even started her series!). None of these are terribly satisfactory alternatives.

Furthermore, writing, like music and painting and most other arts, gets better with practice. Lots of writers have started off by writing a completely unsellable first novel. (Hardly anybody does this on purpose, but it still happens quite a lot.) If this turns out to be the case for you, and your first novel is Volume I of a trilogy, then the whole trilogy is unsellable — nobody is going to buy and publish parts 2 & 3 without part 1 to start things off. (There are ways around this, but they all amount to making each book stand on its own, rather than telling a continuous story over the course of three or four books as is commonly done in trilogies.) Even if the first book sells, it is highly likely that a first-timer will find Book 3 noticeably better than the already-published series opener, and Book 5 even more so. This is vastly disturbing to some writers.

On the other hand, passion counts for something. So my first advice to someone in this situation is usually “Do some thinking, and if you still want to try this, go for it. But go with your eyes wide open.”

Eyes wide open means:

1. Thinking hard and clearly about your story, and whether you actually have enough for five novels plus spinoffs, or whether what you have is two books’ worth of story and a ton of notes and appendices.

2. Considering how you are going to feel and what you are going to do if your massive five-volume novel-and-spinoffs don’t sell. As a first-time novelist, you’re going to have to write them on spec (meaning, without a contract). Are you obsessed enough with this story to spend years writing it regardless of whether it sells? (Yes, you can self-publish it on Amazon now, but the same question applies: will you be happy if it doesn’t sell?)

3. Think about leaving yourself space for you and/or your story to change on you. If you get to the middle of Book 3, where your heroine visits the dwarves, and you suddenly find yourself desperately wanting to write the story of what happens if she stays there, you are not going to be happy if you have locked yourself into the typical quest narrative that requires her to continue on her quest to defeat the Evil Overlord. If you develop a passionate interest in climate change, but you can’t write about it because the imaginary world you’ve invented doesn’t allow for that, you are likewise going to be unhappy. You can’t plan for everything, but you can deliberately leave yourself some wiggle room.

4. Think about an exit strategy. If you are writing a massive five-volume novel with a clear ending, and you get bored or grow out of it in the middle, you are up a creek. If you have nineteen individual adventures planned that take your hero from grad school through becoming Galactic President, it’s a lot easier to just stop at the end of one of the books.

If you have your heart set on a story that can only be told in many, many pages — well, do it. You’re far more likely to do a good job on a story you desperately want to tell (no matter how idiotic a choice it may be in marketing terms) than on something you’re just doing “to fit the market.” But if you are thinking of writing a trilogy or series because you see a lot of them out there, and it kind of vaguely looks like a good idea because maybe it would sell … think again. Tell the story you want to tell, and let it be as long as it needs to be. Worry about marketing it later.

December 8, 2013

Uses for Plot Shapes

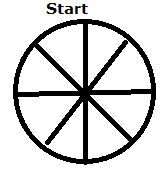

So we come to why I have been thinking about plot shapes for the past week. It started with an article on the traditional triangle plot that mentioned in passing that there were other possibilities, but didn’t give them much consideration beyond that. Naturally, this got me thinking about what some of the other possibilities were, and digging through my collection to find them.

It also got me thinking about what use knowing about different plot shapes is to a working writer. A lot of analysis of writing doesn’t help much when it comes down to actually producing a story; it’s only good for understanding it after it’s been written. For a writer, that means at the revision stage.

Recognizing the shape of the story – whether it’s a triangle, spiral, beads, or wheel – means that if the shape is a bit lumpy in the first draft, you can smooth it out in revision. If you have a nice spiral with a funny kink in it near the end where you were trying to make it have the peak of a triangle, you can spot the problem and fix it. If your circle plot feels more like an oval or a flat tire, you can pump it up til it’s nice and round. If there are gaps between beads, you can add whatever is needed.

But if the only shape you are aware of is the triangle, you aren’t likely to spot the missing bead, and you’re likely to spend loads of time trying to build things up to a peak or turning point that doesn’t belong on a circle or wheel or spiral…or at least, that doesn’t solve the plot-problem that has pulled the circle out of alignment. Fixing the wrong thing never helps, and usually makes things worse.

This much is fairly obvious. But then I thought a bit more, and it occurred to me that understanding shapes and possible shapes of stories is really useful at the other end of the process, too – that is, during the development and prewriting stage. Because some ideas are better suited to one plot-shape than to others.

Years back, I was discussing this with a writer who had an idea for a story that he thought was a character study – seven different people’s views of a particular world-changing incident and its aftermath. He was having problems figuring out what the climax of the tale ought to be, since according to everything he knew, the world-changing incident ought to be the big finish, but the stories he wanted to tell came after that.

What he failed to realize was that he had a classic wheel shaped plot; his big finish was not going to be a world-changing incident within the story, but rather whichever of the seven views of it that gave the reader a final understanding of it. Once he knew that, he could quit worrying about how to force the idea into a triangle shape that didn’t suit it, and get on with planning out what each viewpoint character would see and think, and what order to present them in.

It is also perfectly possible to go looking for an idea that suits one of the less-common plot shapes. I personally tend to come up with triangle shaped plots as a general rule. It’s possible that I will one day have an idea that is well-suited to one of the other shapes instead, but it is far more likely that if I want to write that kind of a story, I’ll have to start with the intention of doing something that suits a wheel (for instance), and cast about for an idea that I like. One can also look at an idea that doesn’t obviously need to be one shape or another, and try on several different possibilities, to see if one of them strikes more sparks than another.

Finally, if you know what shape you expect your plot to be, you have a better chance of spotting problems during the actual writing phase, before they pull things wildly out of shape in ways that will take a lot of revision work to fix. If you notice that the rising action leg of the triangle is flattening out, you can drop back a few scenes or a chapter and add more tension; if you realize that the spiral is getting lopsided, you can put in a suitable bit of action or emotion on the weak side. It is usually a lot easier to make major changes during the first draft, especially if they are the sort of thing that will send ripples through the entire rest of the story (which they always are, whether you intend them that way or not. It’s some kind of law of stories, I think. Or else Murphy).

But there is one more way in which understanding plot-shapes can be useful, and that has to do with the individual writer’s process. I suspect (though I don’t know for certain) that writers’ processes work best on compatible plot-shapes (and probably on different ways of looking at or using characters and background).

For example, I am, as I’ve said before, a very linear writer. The triangle shape comes naturally to me, and almost all my plots follow that pattern. I have one WIP that has given me fits for years, in part because it took me forever to realize that it doesn’t follow my usual process. It’s a spiral (I think), so I am going to have to approach it more consciously and think more about the story shape, because it doesn’t fit comfortably in my normal, linear process the way triangle stories do. I know writers who use stringing beads or circling in on something as their central metaphor for describing the way they develop and work at their stories, and I think they might find circular or beads-on-string plot shapes easier to write than triangles.

For this to be useful, one has to recognize both one’s typical process and the shape of the plot one is trying to write, so that one can identify any mismatch and try to compensate for it consciously. Or possibly recognize the difficulty and switch to some other story that fits one’s process better.

December 4, 2013

Plot Shapes III: Beads on a String and spokes on a wheel

I’m sure all of you have been waiting for the e-book with baited breath. Wrede on Writing goes live tomorrow, December 4th. It’s the first time I’ve had THREE sets of galleys to look over (epub, mobi, and the pdf that they’re using for the hardcopy version). It also got put together with stunning speed to make the Christmas rush (they turned the copy-edit around in 24 hours, so I can’t really complain that they only gave me two days each to look at the galleys. Even though I want to.)

For those who don’t already know, this is a collection of my blog posts and classroom handouts, edited and rearranged to follow some vaguely logical order. If you like reading this blog, get a copy and give it to a writer friend for Christmas. If you hate my advice, get a copy and give it to an enemy…

Enough with the shameless self promotion. Back to talking about plot shapes.

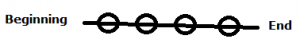

Yet another plot shape to consider is the one I think of as beads on a string.

This one has a central core that connects everything, even though the scenes or chapters or sections that make the “beads” aren’t necessarily or obviously connected by anything else. Often, each “bead” is a different viewpoint, as whatever-it-is moves from one place/character to another, the way the jeans do in The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants. It can also be something like the original Star Trek series taken as a whole, where each “bead” is an episode in the ongoing mission (whereas, as somebody pointed out, each episode taken individually is circular, putting the main characters right back where they started). One novel that I remember reading but can’t place at the moment was a great fat bestseller-like thing that followed a gemstone from being dug up by a medieval miner, to the jeweler who cut it for a nobleman, to the Renaissance pawnbroker who took it as a pledge from the nobleman’s wastrel grandson, and on through different characters who owned it during the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, and of course World War I & II.

A beads-on-a-string plot often looks a lot like a fix-up book (and sometimes it is, when the author has written a series of short stories that deliberately follow portions of a larger plot-arc, like John Brunner’s Crucible of Time). Or it can be something like Dr. Robert L. Forward’s Dragon’s Egg, in which the alien species the humans are trying to contact live at such a significantly faster rate that, to them, decades and centuries go by between each message, and each chapter or section from the alien’s viewpoint must therefore feature a different main character and different social and cultural problems as they essentially move from being a primitive civilization through several thousand years of development (from their perspective) over a couple of weeks (from the perspective of the humans).

Related to this, but not the same, is the wheel plot shape:  It’s related to the beads-on-a-string because each section or wedge is a completely different view of the same central thing or event (the hub). Unlike the beads, which are independent of each other and only connected by the central thread, the wedges are different takes on the same thing, so they necessarily cover similar ground.

It’s related to the beads-on-a-string because each section or wedge is a completely different view of the same central thing or event (the hub). Unlike the beads, which are independent of each other and only connected by the central thread, the wedges are different takes on the same thing, so they necessarily cover similar ground.

The wedges can be differing accounts of the same event, as in the movie Rashomon, or differing story forms (poetry, myth, legend, song, “nonfiction”) that interpret and reinterpret the same story, as in Jane Yolen’s Sister Light, Sister Dark. Unlike the beads-on-a-string, though, the story could theoretically start with any one of the “wedge” bits, as they are all focused on the same central event or story at the same time. Usually, the author arranges them to get the maximum effect – Rashomon would not be nearly as effective if the woodcutter’s story came first, or if the samurai’s story was told before the bandit’s version or the wife’s. Still, the stories are independent enough that you could start with the samurai’s story if you wanted. Everything would still make sense (as much as it ever does), it just wouldn’t have quite the same impact.

Again, you don’t see a lot of action plots that have either of these shapes, though I think my examples demonstrate that it’s not only possible for an adventure plot to work in this shape. And using one of them instead of the usual triangle-shape can lead a story in some really, really interesting directions.

In both of these cases, there is usually at least a bit of build-up to something, whether it’s keeping the most dramatic story for last or twisting the reader’s interpretation/reinterpretation with a major revelation near the end. Still, the overall story shape just doesn’t fit the traditional triangle I started with in the first post of this series. The individual beads or spokes often do follow that pattern, though, especially when each is a complete story of its own.

This adds a whole enormous layer of complexity to the topic: combining and layering different plot shapes. Novels have plots and subplots, and each can have its own shape (as with the Star Trek episodes I mentioned earlier, which fit the triangle problem-obstacle-solution shape in the action plot, leave the characters circling back to exactly the same place at the end of each episode, and work as beads-on-a-string when you look at the whole season at once).

Which brings me to the reason I got to thinking about all this in the first place, which I’ll talk about next time.

December 1, 2013

Plot shapes II: Circles and Spirals

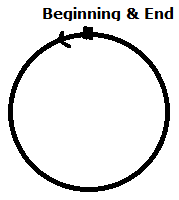

The traditional plot shape I discussed last time is vaguely triangular; it starts at a beginning, tension rises as the protagonist faces and overcomes (or doesn’t) a series of obstacles, until things reach a peak at the climax or turning point; after that, it’s all downhill until the end. This is the shape of almost all action and adventure plots, and it’s really fairly straightforward.

The circular plot shape is harder to explain, partly because we’re so used to the traditional rising-peak-falling triangle. I find them really frustrating, because the protagonist never really gets anywhere and nothing changes – which is, of course, the whole point. The protagonist may wander through a lot of places and meet a lot of people, but eventually he arrives back where he started. Exactly where he started. And nothing has changed, and the protagonist hasn’t changed (except for having some nice/nasty memories of his adventures).

Very few action-adventure stories use this kind of plot, and when they do, they usually have the much-derided “…and then he woke up and realized it was all a dream!” ending. Lots of action-adventure stories, however, look at first glance as if they are circular, because in many of them the hero’s reward for saving the kingdom or slaying the dragon is to be allowed to go home, back to the ordinary life he left in order to go adventuring.

Look a little closer, though, and it isn’t really the same ordinary life – it’s better. Things have changed as a result of the story. Sam ends up back in the Shire, but he’s married Rosie and Frodo has left him Bag End, making him a respected hobbit of substance. Or, sometimes, it isn’t the ordinary life that’s changed, it’s the hero, who may have been so altered that, like Frodo, he discovers he can’t stay, or who may simply have come to appreciate deeply the things that, before all his adventures, he took for granted.

The two obvious examples of circular plots are Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake and Delany’s Dhalgren, both of which open in the middle of a sentence and end with the first half of the same sentence, so that if you had the book on a mobius strip you could just keep reading on forever. Both get described as “enigmatic” – lots of stuff happens, but it’s never quite clear where it’s going or what it means…because really, it’s all heading right back where it came from. But circular plots can also be Marvelous Voyages – the sort of story where the protagonist(s) go off to Arcturus or Wonderland, meet strange and interesting people and find out all about how this odd new world works, and then go home.

The main difficulty with a circular plot shape is keeping the reader interested and giving them enough meat that they don’t get frustrated when they realize that the protagonist is going to end up right back where he/she started. This is why Marvelous Voyage plots tend to work as circular structures: if the writer has come up with enough cool and interesting stuff for the protagonists to find out about, the reader can get carried along with the fun even when there’s no apparent goal or obstacles or any of the things we’ve been taught that stories need to have.

Spiral plots are related to circular ones in that they are usually getting somewhere new. The protagonist keeps revisiting something, but each time it comes around, it’s on a different level or from a different perspective. It can work well with action-adventure, especially with a Man-Learns-Lesson plot or subplot: first, the young princess is spirited away from the rebels taking over the castle, without making any choices herself; later, she’s grown up and chooses to flee again rather than endanger the people who’ve raised her; later still, she chooses to fight back, or perhaps decides to sacrifice herself to stop the fighting. The situation – being attacked by rebels – keeps recurring, but in different places and times, and what the princess is capable of doing (both physically and emotionally) keeps changing.

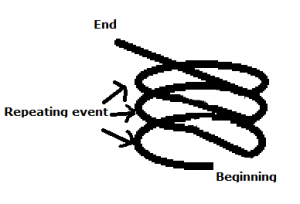

The plot can spiral around all sorts of things: a place, a person, an object, a situation, a memory, a discovery. It can also spiral inward, getting deeper and uncovering new information or new layers of meaning with every go-around until it reaches a climax of revelation or discovery, or it can spiral outward, with the protagonist learning and growing with each iteration until he/she can escape the cycle. You can also have a nice, even spiral, like a spring (the way I drew it above), or one in which each new circle is a bit larger than the last as the stakes or the main character’s knowledge and ability to act keep growing.

Two more, and then I’ll get around to explaining why I’m going on about all this.

November 27, 2013

Points and Turns

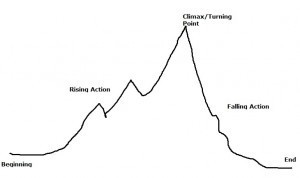

When I was in school, back in the Jurassic, I was taught the basic plot structure and its variations: beginning, rising action, climax or turning point, falling action. The chart that went along with it looked something like this:

For years and years, I thought this was the only plot structure there was; the only things that changed were how many peaks and valleys you had in the “rising action” part and where in the story the turning point came (it could, my teachers told me, happen as early as halfway through or as late as 90% through).

The climax, also called the turning point, got the lion’s share of attention in my classes. It was supposed to be the point of greatest tension in the story, the point after which, however much story there was to come, the end was inevitable. (This always made me wonder why the “turning point” in a Sherlock Holmes story wasn’t always the moment in the first few pages where Holmes says, “Yes, I’ll take the case.” Because from then on, the ending was inevitable…)

Somewhere in the past thirty or forty years, things have gotten a lot more complex. For one thing, at least half the things I read talk about “turning points” – plural. People seem to mean one of two things by this: either they are talking about the smaller peak-points on the “rising action” side of the graph, where something tense and dramatic happens that changes the direction of the story, or else they are talking about the specific spots in a three- or four- or five-act story structure where the story moves from one “act” to the next.

This change in definition has caused a certain amount of confusion. Most stories have one, and only one, climactic moment in which the outcome is settled. There may be many points of great tension and drama, but there is only one that is the highest point. On the other hand, there are plenty of stories that take a sharp turn away from whatever the reader had been expecting, and these do feel a lot like whipping around a sharp corner at high speed, so it’s perfectly understandable that these points end up being called “turning points,” even though they aren’t THE turning point or climax.

There is a good deal to be said for both views, if you’re a writer…and if you are a writer, you don’t have to worry about whether they can both make sense simultaneously. You only have to worry about whether the way of thinking about turning point(s) you’re currently using is currently helpful to you.

Some writers, for instance, can get totally bogged down in the miserable middle of a novel if they only ever think about the big climax they’re aiming toward. It’s too far away and it’s all uphill from where they are. They find it much more helpful to look for tense, dramatic moments of change – lesser turning points – that are closer to hand. It’s a lot easier to get motivated to write the cool scene in the next chapter where the heroine makes a life-changing discovery or finally gets the sword she needs to slay the dragon than it is to get motivated to write the battle with the dragon that’s still twelve chapters off, even if the giant dragon-battle is much cooler.

On the other hand, if all the writer ever looks at are the cool scenes that are coming up, they can easily lose track of where they’re going. It is therefore advisable to stop occasionally and ask oneself whether one is still making progress toward that big, dramatic, final climax…and if not, why not. If a new climax has presented itself, one that’s bigger and more dramatic, that’s fine; but if one is merely wandering in circles in the bog, writing lots of little “turning points” and revelations that don’t actually get the story anywhere, one may have to murder more than a few of the darlings that have been distracting one.

It is also possible for a story to have a double climax, especially if it has an emotional plot that has equal or nearly-equal weight with the action plot and the climaxes of each part can’t possibly take place in the same scene. In this case, readers will generally perceive one of the two as THE climax, but different readers will pick different peaks, depending on which plot they were more interested in. As long as they all go away satisfied, this is fine, but if the writer shortchanges the climax of one plotline because he/she is more interested in the other, one set of readers will end up unhappy. A similar problem can arise when the author is writing a braided novel with an ensemble cast, and likes or dislikes some characters or plotlines more than others.

Noticing these problems is half the battle, or more…or rather, if you don’t notice, the battle is lost before you even start. You can’t fix what you don’t realize is there or recognize as a problem. It is, however, up to the writer to decide whether he/she works most productively and effectively by doing periodic checks during the first draft, or by writing the whole thing and then ripping it apart during the revision stage, as necessary.

And of course, this particular plot structure isn’t the only one there is, though it is possible to shoehorn an awful lot of stories into this format. Next time, I’m going to talk about some of the other possibilities.

November 24, 2013

My Writing Life: An Adventure

You are standing in a hallway at nine in the morning, facing a dining room/kitchen to the south. To the west are stairs up. To the north is an office.

Your head feels rather fuzzy.

>Go north

You are standing in a cluttered office, full of paper, books, and office supplies. There is a desk here. There is a chair here. There is a cat here.

The cat jumps onto the chair and looks at you expectantly.

>Sit in chair

You can’t sit in the chair; there’s already a cat in it.

>Pet cat

The cat purrs.

>Pet cat

The cat purrs. It doesn’t seem to be going anywhere.

You are standing in a cluttered office, full of paper, books, and office supplies. There is a desk here. There is a chair here. There is a cat sitting in the chair.

>Squint at desk

The desk contains a computer, a cordless phone, a printer/scanner, three DVDs loaned to you by friends, an overdue library book, a pencil holder full of pens, a cookbook, and a stack of papers.

>Leave office

Hey! Where are you going?

>I can’t deal with this right now.

Oh, all right. You are standing in a hallway. To the south is a dining room/kitchen. To the west are stairs up. To the north is an office.

Your head still feels rather fuzzy.

>Go south

You are in a dining/kitchen area. There is a teakettle here. There is a can of cat food here. There is an empty cat bowl here. There is a mug here. There are 17 different kinds of teabags here.

>Make tea

You fill the teakettle and set it on to boil.

>Select tea

Caffeine or decaf?

>It’s nine in the morning! I want CAFFEINE!

All right, all right, I was just asking.

You select a strong Irish Breakfast teabag and place it in the mug. The kettle is boiling.

>Make tea

You finish making your tea and drink some. Your head clears immediately.

There is a half-full teakettle here. There is a mug of tea here. There is an empty cat bowl here. There is a can of cat food here.

>Open cat food

The cat runs in from the office and winds around your legs, meowing plaintively, as you fill the cat bowl with food.

>Give food to cat

The cat starts eating the food.

>Take tea and go back to office

You return to the office. There is a desk here. There is a computer here. There is a chair here.

>Sit in chair

Finally!

>Turn on computer

The computer whirrs and beeps. Eventually the main screen comes up.

>Check email

Do you really want to do that? You’re supposed to be writing.

>Check email

You have three fan letters, twenty-six pieces of spam that got through the spam filter, nine emails from the mailing list, an invitation to tea, and two emails from your agent

>Delete spam

You delete the twenty-six pieces of spam email. The computer chimes. You have three fan letters, one piece of spam that got through the spam filter, fourteen emails from the mailing list, an invitation to tea, and two emails from your agent.

>Accept invitation to tea

You email an acceptance to tea on Saturday. The computer chimes. You have three fan letters, six pieces of spam that have gotten through the spam filter, twenty-one emails from the mailing list, and two emails from your agent.

>Read agent emails

The first email is an urgent request to contact the agent by last Friday to discuss the proposal for your next book, which you were supposed to have finished last month; reading between the lines, there’s a potential offer she wants to discuss.

The second email is an auto-notice that your agent is out of town for the next two weeks, with no phone or email.

>Oh, crap.

I don’t understand that.

>Panic

Panicking won’t help. The phone rings.

>Answer phone

You answer the phone. It’s a telemarketer. He talks very fast for five minutes and you finally have to hang up on him because he doesn’t give you time to say you’re not interested.

Your computer chimes. You have mail. Specifically, you have three fan letters, twelve pieces of spam that have gotten through the spam filter, fifty-two emails from the mailing list, an email with attachment from a member of your critique group, and an email from your editor, also with an attachment.

>Read editor’s email

The copyedit for your ebook is attached. They want it back by 4 p.m. EST tomorrow. There is the distinct implication that if you don’t get it back in time, the publisher will have to delay publication and you will miss out on any Christmas sales.

>Open ebook file

Your ebook reader doesn’t understand this format.

>Argh.

I don’t understand that. Your computer chimes. You have mail. You have four fan letters, fourteen pieces of spam…

>Close email reader

I wasn’t finished yet!

>Close the damned email reader!

All right, all right. You close the email reader.

>Get on Internet and search for free ebook reader

You open your browser and type in a search. Your computer hiccoughs and informs you that it cannot complete the search because you have no Internet connection.

>What! I had one seconds ago!

Your Internet connection is not available.

>Check router

All the lights on the router are out

>Out? Shouldn’t some of them be red? Wait a minute… Check cord on router

A cat is sitting on top of the power cord that leads to the router. The end of the cord appears to have come unplugged from the wall.

>Throw cat out of office and close door

The cat makes plaintive noises outside the door

>Ignore cat. Plug in router.

After a minute, the lights on the router light up and turn green.

You have an Internet connection.

The cat is making more plaintive noises outside the door.

>Ignore cat. Download free ebook reader.

After some searching, you find and download a reader that can open the file your publisher sent you.

Your tea is cold.

>Install ebook reader. Go to kitchen for more tea while file is installing.

You open the office door. The cat shoots inside and hides under the desk.

>Ignore cat. Get tea.

You proceed to the kitchen and make tea.

>Return to office

The office seems more cluttered than when you left.

>Examine office

You are standing in a cluttered office, full of paper, books, and office supplies. There is a desk here. There is a chair here. There is a cat sitting on a stack of papers by the desk, looking smug.

>Examine desk

The desk contains a computer and a printer/scanner. The phone, the DVDs, the books, the pens, and the papers have all been shoved onto the floor.

>Yell at cat

The cat looks smug and unimpressed.

>Throw cat out of office.

You put the cat out and shut the office door.

>Sit in chair. Open copyedit file

You open the file your editor sent you. It is completely full of comment balloons and changes to the text. Half of the changes are spot-on, but the other half will require rewrites or explanations, some of which will be extensive. This is not going to be quick.

>It has to be quick; it’s due tomorrow.

I don’t understand that.

>Lucky you.

I don’t understand that.

>Work on file.

You spend several hours working on the copyedit file. You are done with the first 10,000 words. You have 70,000 left to go.

>Call friends and cancel dinner appointment. Work on file.

You work on the copyedit file some more. You are half done. Your brain is getting fuzzy. Your tea is cold.

>Hit save. Go to kitchen for more tea.

You save your work.

You stumble over the cat on your way to the kitchen.

There is an empty teakettle here. There are 17 kinds of tea here. There is an empty, dirty cat food bowl here.

>Pick up cat food bowl and put in sink.

You put the cat food bowl in the sink. You notice there are no other dishes in the sink. Possibly because all you have had so far today is tea.

>Um, yeah. Check refrigerator.

The refrigerator contains half a gallon of milk, a jar of natural peanut butter, every kind of condiment known to man, three raw eggs, two hardboiled eggs, some cheese –

>Stop right there. Eat breakfast.

It’s lunchtime.

>I haven’t had breakfast yet. Eat breakfast. Eggs, cheese, toast and a glass of milk.

You can’t make toast. You’re out of bread.

>Fine. Eggs, cheese, and milk, then. Eat breakfast and get back to copyedit.

You eat breakfast, dump the dishes in the sink for later, make more tea, and go back to the office. You spend the afternoon working on the copyedited manuscript.

There is a blinking light in the bottom corner of the computer screen.

>Hit save. Check blinking light.

You have unread mail, and your computer wants you to open your email reader.

>Check time

It is 7:12 p.m.

You have unread mail. Your tea is cold. You are slightly more than half done with the copyedited manuscript that is due at 4 tomorrow afternoon, but you have left the hardest stuff for later. You are a month behind on the proposal for your next book. You have a story to read and critique for your crit group meeting on Sunday. You have not picked up the papers, pens, and books that the cat shoved onto the floor. You have not had dinner. You have a blog post to write. One of your cats is making noises in the living room of the sort that mean there is a hairball in the offing.

>The heck with it. I am going to order pizza and spend the rest of the night watching Marx Brothers movies.

November 20, 2013

Raw Material

Anyone who hangs out with professional writers for very long will eventually hear one of them say “I couldn’t get away with that in a novel” or “If I put that in a story, nobody would believe it,” and they’ll probably hear it sooner rather than later. It’s the bane of fiction writers everywhere. Years ago, I ran across a related anecdote that went something like this:

A professor of creative writing was giving a student comments – mostly negative – on the story he had just submitted. In particular, the professor had a number of things to say about the implausibility of the plot, the lack of apparent motivation for the character’s actions, and the unrealistic nature of specific events. The student got twitchier and twitchier, and finally burst out, “But that’s what really happened! It was just like that!”

The instructor looked at the student for a minute, and then said, “I believe you. But you still have to make me believe your story.”

Many writers use incidents from real life in their writing. “It really happened” is, however, a terrible justification for doing anything in a novel…if it’s the only justification for doing it. There are a number of reasons for this, first and foremost the fact that real life doesn’t have to have a coherent plot (or make any sense at all, actually).

A lot of beginning writers find this more than a little confusing. They have been told repeatedly that real life is material; if it’s material, then surely it should go into their stories! What they don’t realize is that real life is raw material. If you want to build a car, you don’t slap a bunch of iron ore, some sand, a rubber tree, and a couple of cows together and call it good; you have to take the raw materials and turn them into steel and glass and rubber and leather, and then into car parts and windshields and tires and seats, and then you have to put all those pieces together in the right places. Then you finally have a car.

Novels are a model of reality, not a transcription of it. Authors take the raw material of real life events and give it explanations and motivations and consequences, then turn it into characters and plot and put them together into a coherent story. Even the most realistic fiction doesn’t resemble real life anything like as closely as we pretend it does.

This is most obvious in dialog, where a word-for-word transcription of an actual conversation on a bus or at a restaurant will instantly demonstrate how different dialog is from the way most people actually talk, but it is just as true for every other aspect of a novel, from character complexity and motivation to plot twists.

For instance, take forgetting things. In real life, people forget important stuff all the time, from their car keys to their anniversary date. In fiction, one has less leeway, especially if the consequences of forgetting something are potentially fatal. “Ooops, I left my sword in my other scabbard” just doesn’t work in anything other than a really broad parody.

Real life doesn’t have to be convincing. It is just there, happening that way, whether we like it or not. Novels, on the other hand, are deliberately constructed. Every action, incident, character, and place in a novel is there because the author put it in, and on some level readers know it. It’s artificial, and that means the novel-writer has to do a bit more work to convince the reader that the story is “real,” compared to the journalist who can simply report a wildly unlikely event.

If something happens in a novel, we expect there to be an explanation, a reason, and a payoff, or why would the author bother to put it in? That’s why I started off saying that “it really happened” can’t be the only justification for putting something in a novel. There has to be a reason internal to the novel for that incident or description or whatever to be there; it has to have a payoff within the story. “Payoff” can mean that the incident starts or ends a chain of plot events, or that it results in a new discovery or a revelation of a character’s backstory, or even that it displays something new about the nature of the world the characters are living in, but whatever it is, it has to make sense in the context of the story.

“Making sense” is a matter of motivation and foreshadowing, setup and consequences – all the things that you may never know when it comes to a real-life incident. You may never know why a stranger came up to you in the hotel lobby and said “Will you hold my duck for ten minutes?” and handed you a duck, then disappeared for a while before coming back, thanking you, and giving you a ten-dollar bill, but if you put that in a book, you not only had better know who the stranger is and why he need somebody to take his duck for ten minutes, but you had better also make sure the reader finds out at some point what all that was about and why it was relevant to the main story you’re telling. Unless, of course, you are writing the sort of surreal novel in which that kind of thing is routine, but in that case the incident does “make sense” in the surreal world of your story, and may even have something to do with the three angels who are trying to catch a cab just outside the hotel.