Patricia C. Wrede's Blog, page 41

February 25, 2014

Yet more plans…

OK, since there seems to be yet more interest in plot planning and prewriting and how to do it, you get still more posts on the subject. This one is on alternate ways of doing plot-related planning; next one will be on the kind of outline you do to submit to an editor and how it is different.

The important thing to remember is that the form of any pre-writing plot plan depends entirely on the needs of the particular writer who is doing the planning. It can be anything from a conglomeration of bits of dialog, scene snippets, and occasional notes that, taken together, indicate where and how the story will proceed from one turn to the next, to a highly organized and systematic scene-by-scene summary, to a series of diagrams that look like a programmer’s flow chart. The only criteria is that it helps that particular writer work out whatever aspects of writing he or she needs to have thoroughly clear and worked out prior to beginning to write. If it doesn’t help, it’s totally optional (I almost said “a waste of time,” but some people have a lot of fun doing elaborate pre-writing stuff, and fun is never a waste of time. So, optional.)

Plot-planning can be done in lots of ways, and the process can be very different from the eventual end product. Some writers get partway through a particular process, and by that point they know everything they need to know to go on with, so they quit planning and start writing with their plan looking half-finished. It isn’t half-finished; it’s as done as they need it to be. See above paragraph.

The actual process of planning the plot depends on where you are starting from and what bits are the bits the writer finds particularly interesting, exciting, and fun. If what got you interested in writing this story is the three main characters and their relationship, then the plot is probably going to need to showcase that in some way, or you are going to lose interest. If you have a very clear idea of a scene – first, last, or in the middle, doesn’t matter – then that is what you start with. If you have a plot skeleton or idea, well, that’s what you start with (and yes, people who start here sometimes also need to do planning).

You then need to think for a minute about how you think. If you are visual, your plot planning may work best if you start or finish with some of the more visual methods; if you are kinesthetic, moving Post-It-Notes around the coffee table may work better, or making little models out of modeling clay or Legos. (Yes, I know people who do these things. No, I won’t tell you who.)

The first phase of plot-planning is usually brainstorming. There are lots of ways to do this, from writing down ideas on notecards (one to a card, so you can rearrange them later) or making lists of events that could happen and reasons they might, to “mind maps” where you construct a sort of spiderweb of possibilities on the page, to actual decision trees where you try to follow the different decision paths as far as they will take you, rather like a Choose Your Own Adventure book only without all the text. One of my friends refers to this as “the spaghetti stage,” meaning the point where you are collecting as much spaghetti as possible and cooking it a bit, so that later you can throw it at the wall and see if it sticks.

Most writers start with at least a few things they know for certain. Usually it’s a combination of character stuff and events – for instance, I know that one of the secondary characters is an unwanted third child, but I haven’t yet decided on the character’s age within a very broad range (somewhere between ten and thirty, depending on what skills I need to make available to my heroine). So you look at the things you know for sure, and at where you think the story is going or has been, and at what you absolutely have to have to get from what you absolutely know to the other parts you absolutely know. Then you start coming up with all sorts of ways you might get from A to C, and all the various possible reasons your characters could have for going this or that way, and all the other possible subplots you can think of.

Eventually, most writers want to take the mass of possibilities and alternatives and consequences they have come up with (“F is M’s grandfather/uncle/biological father/best friend of one of the above?”) and start sorting them out into something more coherent. This has three parts: making decisions, looking at consequences, and making up more missing bits to connect the things you have decided and/or the effects of the consequences.

To put it another way: a plot is a series of decisions that the characters (both the heroes and the villains) make that leads them toward the eventual outcome. Planning the plot in advance involves figuring out at least some of those decisions – both what they are and which way the characters decide – and then looking at the consequences of each decision and the direction it leads (which might be the direction the writer wants the story to go, or a totally wrong direction, or a new and more interesting direction than what the writer initially thought of), and finally filling in whatever missing bits are needed to make a continuous chain from start to finish.

For some writers, all this is really intuitive; others have to grind their way through various mechanical systems in order to jog their backbrains into settling on one main plotline. There are tons of different metaphors for how this process works, like the cooking spaghetti one above. Some writers think of it like putting quilt pieces together in a pattern; others, like stringing beads to make a necklace; others, like putting Legos or Tinker Toys or jigsaw puzzles together. Some work best if they have a really strictly organized framework to fill in, while some prefer to be a lot more free-form. Even for the most highly structured, though, things are still extremely fluid at this stage of the game. Plot points and objectives and problems and characters can fly in and out of the story as more interesting ideas or links occur to the writer. This is why you probably don’t want to write this up in indelible ink…

The chain of cause-and-effect decisions and actions can be as sketchy or as detailed as the particular writer wants and needs it to be. Some writers are happy with a half-page list of five or ten key plot points; others need a hundred pages or more of detailed scene-by-scene developments. Again, the point is to do as much of whatever kind of thing you, the writer, need to give you whatever it takes to get you going and keep you going through to the end of the best novel you are currently capable of turning out.

If all this still seems a little vague, it’s because there is no One True Way to do this. Every writer I know has a different, highly customized system of working (and I count “sit down and surprise myself” as a highly customized system). All I am trying to do here is give a broad-brush overview, because that is about all anybody can do. From here out, the answer is: you’re a writer; you’re supposed to be creative; make up your own system.

February 22, 2014

If you do want to plan

So if you are going to do some pre-planning before you start writing your book, where do you begin and how do you do it?

As usual, it depends on the writer and the story, but here are a few things to consider:

First, why are you doing the planning? There are two good reasons and one bad one for this. The two good ones are 1) You have tried advance planning before and found it useful, so you are going to keep doing it, or 2) You have never done any advance planning before, but you think that it is likely to benefit you (or you just hope it will help, possibly with some specific problem you already know you have).

The bad reason, of course, is because somebody else told you that you had to do an outline and/or a ton of planning in advance, and so you think you should. If this is you, please reread my previous post, paying special attention to the part that talks about writers with a different process, and then throw away all the planning stuff and sit down at the computer and surprise yourself.

If you fall into one of the first two categories, the next question is whether you have something specific that you hope to accomplish. If you’ve done this before, presumably you know a bit about what works for you and what doesn’t. If you haven’t – is this a complete experiment, or do you know that you never have a decent plot, or you always have trouble with the characters, or your settings and backstory are never as satisfying as you want them to be?

It is important to think about this stuff because what you hope to achieve by planning has a lot to do with what kind of planning you do, and with where you start. Contrary to what the how-to books generally say, there is no one right place to start planning, and no specific type of planning that is right for every writer.

For instance, if you know that you always default to really generic descriptions, your pre-writing planning might focus on places – figuring out where certain Big Scenes will (probably) occur and making up detailed layouts and descriptions of what makes each place unique. Even without a terribly detailed idea of the plot, one usually can pick out at least a few places where the main character is going to do things: their bedroom, living room, and kitchen; their workplace; their favorite post-work hangout; their best friend’s apartment; the woods they’re going to get lost in or travel through. You may need to stop and come up with some more place-descriptions when you’ve written enough story to know what else you’ll need, but you can probably make up enough to get started.

Or if you know that your characters always lack something, you might focus on that aspect – making lists of people who logically might be in the story, given what you know about its plot and where/when it is set (e.g., cab driver and grocery clerk for a modern city; hostler and mudlark for Victorian steampunk). The idea behind this is not to look at characters you already know you will need, but at all the other folks who could be around and might be useful to know about at some point, the minor characters that you might not otherwise think about but who can make events more real-feeling just by running through a scene in the background.

If it’s the major characters who give you fits, you might find writing a description of everyone’s relationship to everyone else helpful. Or possibly one of those fill-in-the-blank character sheets would work for you. Or, since many writers get to know their characters by writing them, writing a couple of scenes from different characters’ viewpoints – scenes that don’t belong in this story, or at least, that you don’t intend to put in it – can help. Roger Zelazny said that he always wrote a few scenes from his main characters’ pre-story, little incidents that had nothing to do with the novel, before he started writing the actual story. This can be particularly helpful for characters who are important to the plot but who don’t have much stage time and/or who aren’t supposed to be viewpoint characters in the main story.

Maybe it’s the names of imaginary places and cultures that’s your particular problem. On occasion, I’ve made up a bunch of place-names and/or first and last names that I can mix and match later, just so I have a bunch of things that sound right to choose from. I find it a lot easier to make up a list of five or ten names that sound sufficiently similar to come from the same background country/culture, and that will be sufficiently different-sounding from my other list of five or ten names from some other background, if I do all of it at once, up front. But some writers have no trouble getting the same effect by keeping tabs on things like that as they go.

The most common problem that drives writers to do pre-writing planning seems to be problems with plot, and there are a gazillion how-to-do-it methods out there. Most of them seem to start with “what do your main characters want?” or “what is your main character’s problem/goal?” which is fine if that works for you. The first time I heard this, I thought it was a brilliant idea; it took me a while to figure out that that is never where I start looking when I look for a plot.

So before you dive headlong into any of the systems that are out there, stop for a minute and think about whether it feels right to you. Not “right” in the “this is True” sense; right in the “this fits me like a custom-made glove” sense. Because you can start with what your characters want, but you don’t have to. You can start with where they are from, or with what they are afraid of, or with wanting to write about a particular event like Carnival in Brazil or a presidential election or the invention of the printing press.

Lately, I seem to be starting with either a completely outside-the-main-character problem (like a natural disaster that is about to break over my heroine’s unsuspecting head) or with the villain’s Clever Plan and/or backstory. Oddly, this doesn’t mean starting with what the villain wants, necessarily; in the current work-in-development, I have a group of people who commit a murder prior to the start of the story. Of the four or five of them, I know what one of them wants and why he decided to help murder the victim, but the other three? No clue, yet. And I’m not worrying about that part at the moment – I’m more concerned with what each of them does in the ten years or so after the murder and what positions they are in at the start of my current story. Oh, and what the “murder victim,” who is perhaps not as dead as they expected him to be, has been doing all this time.

The point is this: if you are going to spend time on this kind of pre-writing and planning, aim it in a direction that is likely to be useful to you. There is no other reason or purpose for doing it. No editor is going to ask to see your detailed diagrams of the furniture layout in the hero’s sitting room (and if you offer them, the editor will likely groan); no publisher is going to want a look at your character questionnaires or early scenes or plot diagrams. And nobody is going to ask whether the final manuscript follows the plot outline you started with (well, except maybe some grad student looking for something to write a thesis on, but even then it isn’t usual). And if all you need is a list of place-names that sound right, you do not have to laboriously work through a detailed plot-plan or setting list or character questionnaire. Just do the parts that you fine helpful.

Because the only reason to do any of this work is if it helps you perform some aspect of the storytelling more easily and effectively. If it doesn’t do that, it’s a waste of time. If doing any of this gets in the way of your writing, if it’s counterproductive, stop immediately and throw it all away. Ultimately, you are trying to write a story, not create the most detailed database of background notes ever made.

February 18, 2014

Advance planning

There are a lot of bits of advice floating around for would-be, wannabe, and newbie fiction writers who are having problems getting started. There are currently a plethora of how-to-write books advocating serious advance planning, ranging from detailed outlining systems, to starting with different sets of character archetypes, to complex setting and worldbuilding development, to one that mandates how many viewpoint characters each book should have given its intended word count, which scene each new viewpoint character should be introduced in, and how often the author should rotate from one POV to another.

They all have one thing in common, and they all fall apart at exactly the same place. The thing they have in common is that all these systems are a way of making assorted writing decisions in advance of actually writing anything. The theory seems to be that what gets new writers (or any writers) overwhelmed and knotted up is the plethora of decisions that have to be made: who the viewpoint character is, where the story takes place, what all the relationships between various characters is, who can/should be in the story and why, what sort of plot structure to use, etc. ad infinitum. Logically, then, if the writer is encouraged to make all these decisions in advance, it ought to then be easy to sail into the story and out the other side. Some of these systems appear to imply that once you’ve worked through their method, the only thing slowing down your production of your novel will be your typing speed.

There are two major problems with this theory. (Well, three, but that gets into where and why they all fall apart, which I will come to in a minute.) The first and largest problem is that not everyone works the same way, and, in fact, the same author won’t necessarily work exactly the same way from book to book. There are plenty of authors for whom any advance planning at all is the kiss of death to their story. Their process is “sit down in front of a blank page and surprise myself.” I’ve done that twice, and for me it feels like working without a net, but Talking to Dragons and Sorcery and Cecelia are two of my most popular books, so it obviously worked better than I was afraid it would.

There are also authors who need more room to maneuver than these systems allow for. They need to be able to get to the scene in the middle of the novel where the heroine needs to find out some critical bit of information and make up something – trained rats, a reverse-hacking computer program, a convenient Oracle – that will let her do it, and then they backfill some mentions of it earlier in the book so it doesn’t look as if it was made up on the spot. This particular breed of author can’t seem to do this if they’ve tied down all of the background, the technology, the backstory, the rules of magic, and the relationships between all the characters in advance.

Which brings us to the second major problem with the theory, which is that making decisions in advance simply in order to have decided something means making arbitrary decisions. “Decide what each and every character wants,” the system says, so the author goes down the list assigning a want to each character just to have something on the list. They then start developing a plot based on Character Q wanting a house in London, all the time knowing somewhere in their heart of hearts that “wants a house in London” was pulled out of their left ear.

Arbitrary decisions have no justification behind them, and they are therefore easy to change. This is good in one sense, because it means that the author can let go of them when she is suddenly hit by inspiration and realizes that Character Q really wants to live up to his father’s image, and the house in London has nothing to do with anything. It’s bad in another sense, because it means that every bit of backstory, plot, and character interaction in the plan that depended on Q wanting a house in London is no longer valid. This can unravel major chunks of plot, especially since that particular sort of epiphany usually strikes in the mid-book when the writer has really been living with and writing the character for a while and has gotten to know them.

And that is the ultimate problem with all these systems: every last one of them reaches, sooner or later, the point where they have to say “Now, sit down and write the first scene.” And not one of them is any help at all with actually writing the darned thing. It’s still a matter of butt in chair, fingers on pen/keyboard. The writer may know exactly what happens, but an outline that says “Matters reach a crisis when Uncle Earn tries to have five-year-old Eff arrested for setting a curse on his house” is vastly different from actually writing the seven-page scene in which Eff and her parents face off against Uncle Earn and a random policeman.

No matter how many things one has decided in advance, each chapter, each scene, each paragraph still has to be written one line at a time. No matter how much the writer knows about magic or the personalities of the people involved, there are still word-by-word decisions to be made: who will speak first, Eff or Uncle Earn or her parents or the policeman? In what tone? Exactly what does Uncle Earn say; “Officer, arrest that child!” in a commanding tone, or “Eff, why did you curse my house?” in a sad one, or “She’s the culprit!” in an accusing one? Exactly how would he phrase it? Who answers him, in what tone? Does anyone interrupt Uncle Earn or the next speaker? Since Eff is the viewpoint, where is her attention and what does she notice first about each of the people who is there? How does she describe what she sees and feels?

Knowing how the Rothmer sitting room is furnished does not help with any of these decisions. Knowing what the characters are like may help somewhat, but it’s still not going to make any of them easy, especially since most writers I know don’t think in terms of making thousands of tiny decisions, they think in terms of “OK, how do I start this scene? What happens?” When the fingers hit the keyboard, it’s usually a matter of feel and intuition, not word-by-word micromanagement.

A more detailed summary of the action (something like “Eff is summoned to the sitting room, where she finds her Uncle Earn and her parents waiting with a policeman. Uncle Earn accuses her of cursing his house and demands that the policeman arrest her; after a short argument between Eff’s father and Earn, the policeman announces that Eff is too young to be prosecuted under the law and leaves. Uncle Earn persists in his accusation until Eff’s mother steps in, informing him that she has had enough of the way he and his family treat Eff and her brother. Eff’s father agrees, and Uncle Earn departs in disarray”) would have been a great help to me if it were the sort of thing I can do in advance; unfortunately, I can’t ever seem to get down to that level of detail until after I have actually written the scene. And while it lays out the main action for the scene, it still doesn’t do anything to help with the actual phrasing of the dialog, or with the balance between dialog and narrative, or with the ebb and flow of the physical action and the emotional reactions of each character.

Planning is different from actually writing the scene. It can help, if you are the sort of writer whom planning helps (I find it very useful, to a point), but you still have to write the scene. And I don’t think there can be a system to walk writers through the actual writing part, because if there were, somebody would write a program that could do it and we’d all be out of a job.

February 15, 2014

Grammar, Syntax, and other Actual Rules

Spelling, grammar, punctuation, syntax. For a lot of would-be writers, they seem to be love ‘em or leave ‘em – which is to say, many of the folks I talk to have either an absolute slavish devotion to formal grammar, punctuation, or else a firm conviction that such things exist only to give copyeditors something to do (and writers something to fight with them over). As usual, the truth is somewhere in the middle.

The most important thing for writers about the standard rules of English is that if you don’t know what they are and how to apply them, you are the equivalent of a surgeon attempting to operate on someone’s brain with a rusty Bowie knife and a longsword. If you don’t have the right tools for the job, the job is going to be a whole lot harder to do. And if you don’t know that the right tools even exist, you are unlikely to go looking for them.

The folks who think grammar and syntax are the copyeditor’s job are missing two important points: first, if you don’t know what standard English is and how it works, you won’t know when you are breaking those rules by mistake and, equally, you won’t be able to break them on purpose to achieve a specific effect. (And there are a lot of useful specific effects you can get from “breaking” certain specific rules of grammar.) Second, a writer who “leaves all that to the copyeditor” is giving the copyeditor the power to determine those effects, which can significantly change the meaning that the writer intended. The classic example is the unpunctuated sentence “Woman without her man is nothing” which can come out either “Woman, without her man, is nothing” or “Woman! Without her, man is nothing.” Punctuation is power…

The folks who insist on applying every rule of standard English grammar and syntax, regardless of any other consideration – indeed, some of them insist that there are no other considerations. They are the equivalent of a carpenter who insists on using his hammer for everything, including trying to saw a board in half. English is an enormously flexible language, and that flexibility can be enormously useful to writers if they understand it and use it correctly.

At this point, some earnest person nearly always asks me when and how they should abandon their formal grammar and syntax – essentially, asking for rules about breaking the rules.

What I always want to say is, “Sir or madam, there aren’t any.” Because the middle of the spectrum that starts with the rules-bound on one end and ends with the rules-averse on the other is a wide, fuzzy gray area scribbled with arrows and circles labeled “style” and “conversation” and “viewpoint” and “context” and innumerable other things. But saying “there aren’t any rules” isn’t going to help any, so instead I talk about context and feel and style and give some examples of places where a strict reliance on the rules for formal and/or standard English is likely to be detrimental to a piece of fiction.

First among these is dialog. I put it first because dialog occurs in almost every piece of fiction, and because it is one of the most common places for people to get hung up on whether or not to apply the rules of grammar and syntax. It’s also a place where it is pretty easy to illustrate why one can’t come up with a set of rules for when to apply those other rules. The first thing is, people don’t speak in the sort of formal essay-writing English to which most of the standard rules of English apply. Any writer who wants to write dialog that actually sounds like someone would say that is not going to be able to stick strictly to standard grammar, punctuation, and syntax at all times.

The second thing is, individual people don’t speak exactly like each other. There are differences in speech patterns that depend on each individual’s background and personality. Since most stories are not about identical twins or clones, this means that most characters will have different speech patterns from one another, and those patterns will be more marked the greater the differences in the characters’ backgrounds is. And if you get right down into it, a lot of the differences in speech patterns comes from different ways of “breaking the rules” of standard English, or rather, from using a slightly different, non-standard set of rules of grammar and syntax, along with a sprinkling of local idioms and turns of phrase.

First-person viewpoint is only second on my list of examples because not all stories are written in first-person. It is, however, a more comprehensive example, in that in a first-person narrative, all the sentences (not just the dialog) have to sound like something the viewpoint character would say or write. Frequently, this means that neither the narrative nor the dialog will follow standard English particularly strictly; occasionally, it may mean the writer will have to write even more formally than usual (say, if the viewpoint character is an extremely fussy English professor who makes a point of being more correct than anyone else even in his/her private journal). Huck Finn says things like “I ain’t seen nothin’ like it,” and for him to say anything else, in dialog or in narrative, would be to destroy the character’s voice. Archie Goodwin (Nero Wolfe’s sidekick and the narrator of most of those mysteries) would never say “I ain’t seen nothin’ like it” unless he was undercover or being sarcastic, and probably not even then.

In third-person narrative, the use, misuse, and overuse of standard English is much harder to pin down. Ultimately, it comes down to the writer’s preferences in style and voice – some prefer a more formal narrative, others want a conversational voice, or something that’s over-the-top like The Worm Ouroboros. The handling of dialog remains dependent on the voices of the different characters and the conversational tone, which nearly always means that the writer is applying two different criteria for “breaking the rules” (one set in the narrative, and a different set for the dialog).

The best (and possibly only) way I know to get a handle on all this begins with knowing what the rules of grammar, punctuation, spelling, and syntax are; after that, one reads widely, notices what other authors do, and does one’s best to figure out why they did it and why one thinks it does or doesn’t work. And after all, coming up with a set of rules for when you can break the rules is silly.

February 11, 2014

The Two Basic Rules

I’ve been saying for a long time that there are only two rules for writing: 1) You must write, and 2) What you write has to work. And I keep running into writers at opposite ends of the spectrum who really, really, reeeeeeaaaally don’t like that.

The first group argues for more rules. Surely there are things that everyone agrees are Bad Writing, they say. Aren’t those Rules For What Not To Do? So I ask them to name a couple, and then point out a couple of places where famous, popular, highly respected fiction writers break those rules and get away with it. Then I get the argument that they only get away with it because they are famous, and we end up in a long, boring discussion of how a rule can’t be the sort of Absolute Truth they want it to be if it doesn’t apply to all fiction, regardless of the name on the cover, and how those highly respected writers “get away” with breaking the rule because a) it isn’t that kind of rule in the first place, and b) what they are doing works (see #2, above). And these people go away muttering unhappily.

The second group doesn’t like having any rules. It’s all about being creative and expressing your inner soul, and rules are so limiting. So I point out that it’s kind of minimal to say that to be a writer, you have to actually write something, and they get all flustered (frequently because they consider themselves writers, but haven’t actually written anything). Then we go through the same kind of conversation about Rule #2 (“So it is find to write stuff that doesn’t work? Wouldn’t you call that “bad writing”?”) and they flounce off in a huff.

What I really want to do to both groups is give them some tea. Because the thing about tea is, it is fairly simple to make (you pour hot water over tea leaves), but in order to make it (let alone drink it) you must make it in something: a teapot, a mug, a teacup, an insulated thermos, a pan. And the necessity of this is so obvious to anyone who has ever made tea that nobody thinks much about it when they say “I’m going to make tea; want some?”

Writing fiction is like making tea that way. There is need for a structure to contain the story; this is so internalized in so many people that they look at me blankly when I say “To be a writer, you have to write. That is, you must put words on paper or into pixels.” The first group, especially, wants more detail than that. But just as there are hundreds of sizes, shapes, and styles of teacups and mugs, there are hundreds of ways of telling stories. As long as the cups hold the tea and the stories get told, it’s fine.

People who want more structure and more rules seem to think that if a little is good, more will be better. But it is very difficult to drink tea out of a mug that has sides that are three inches thick. People who don’t want rules seem to think that their creativity will vanish if it is constrained in any way at all; they forget that if you just set out some leaves and pour hot water over them, the water all runs away and all you have is a muddy spot in the ground or a puddle on the kitchen floor.

The most effective structures and systems and constraints are the ones we don’t notice, because they are so fundamentally necessary that we can’t even consider doing without them. They don’t come from the outside. They arise from the nature of writing and storytelling. They also tend to be positive rules – rules that tell you things you should do. Positive rules are hard to formulate as a by-the-numbers recipe. Saying “don’t use adverbs” gives the writer a nice, easy thing to check (always presuming that the writer knows what an adverb is and can identify it). Saying “Dialog needs to sound like actual people talking” is a lot more general. It has to be, because actual people have many, many different speaking styles, any of which could be used in a story.

“You must write” is a positive rule; it is something you have to do if you hope to be a writer. Actually, it’s definitional; if you don’t write, then you aren’t a writer. You may be a storyteller or a performance artist or an actor or any number of other things that use some of the same story-making skills, but you aren’t a writer if you don’t write.

February 8, 2014

Ending? What Ending?

Endings are a problem for a lot of writers on a lot of levels. People have trouble making them convincing, trouble making them dramatic, trouble keeping them from dragging out or being too abrupt. One of the problems that seems surprisingly common is picking out the ending at all – in other words, some writers just sail right on past the appropriate endpoint without realizing they have done so. This can result in a number of problems – gigantic million-word tomes that weren’t meant to be million-word tomes and don’t work as million-word tomes, plot that wander off into the weeds and never really reemerge, and extremely grumpy writers who complain that they don’t understand what their problem is, but something’s wrong and they can’t stop doing it.

In my experience, there are several different reasons why this sort of thing happens, and the first step, as always, is diagnosis.

The first type of writer (first chronologically, as in, the first sort I ran into) usually has a main character whom they find tremendously appealing. They’re usually planning to write a huge multi-volume saga about their protagonist (sometimes, they’ve already done so). In essence, they want to write a detailed biography of the character’s life, career, and adventures. None of this is a bad thing; the problem is that they get so involved that they can only see their character’s life as a whole, birth to death. It never occurs to them that they’ll have to consciously break it up into coherent episodes…so they don’t.

A slightly different type of writer is…perhaps “easily distracted” is the best description. They start off with a Plan, but somewhere in mid-book, when they are trying to fill up all those pages between the beginning and the climax, they get intrigued by a secondary character, or a chunk falls out of a subplot and leaves them with new and fascinating vistas. The original plot-problem gets lost – yes, yes, we’ll take care of putting the True King back on his throne in Iceland just as soon as we straighten out all the politics of these desert nomads that are just so interesting… Essentially, the main characters get partway through one story and then get sidetracked into a different one. And this process can repeat several times (the desert nomad politics were getting too complicated or the writer was getting bored with them, and then they captured a spy and had to go chasing all the way to China to find out who was behind that plot, and we’re off into a third story without ever resolving either of the first two).

Finally, there are writers who have grown up on complex, braided novels with multiple subplots of varying lengths. In this sort of novel, the author has to start introducing new subplots just a little before the previous set gets wound up (because most of the subplots don’t last the whole length of the novel). The trouble here tends to be that the writers are too good at doing multiple complex plot braids. They can and do keep introducing new plot-arcs, sliding them smoothly in between the events that wrap up the previous plot arc, but they don’t know how to make them come out even. So the braid gets longer and longer and just keeps growing, with no obvious end point in sight.

The general fix for all of these is the same: at some point, the writer has to decide what the central plot-problem is, and then they have to check back periodically to make sure they are headed toward solving it. If something more interesting comes along in mid-book, that’s fine, but they have to stop for a minute and consider how they are going to make the shift. By the time the writer is in the middle, they’ve usually given the reader a pretty good notion of what the central plot-problem is, and they can’t break that promise and still keep most of their readers. What they can do is twist it and expand it – you thought the problem was getting the One Ring to Rivendell and handing it off, but no, the real problem is getting it to Mount Doom and destroying it and Sauron for good. (The real problem is not, however, a digression into dwarven politics when they discover survivors in the Mines of Moria, or haring off on a quest for the Entwives. It’s actually still the same problem the story started with – getting rid of the ring – it’s just become more complicated than anybody thought at the start.)

But whatever the new plot is, it still has a clear endpoint. When the One Ring goes into Mount Doom, that plot problem has been solved. When Aragorn is crowned and marries Arwen, their plot thread is done. When Frodo departs Middle Earth, the emotional wind-up is over. There are still plenty of new stories to be told (that’s a lot of what is in the Appendices), but the story that was being told in The Lord of the Rings is over.

A story that has one main character has one central plot-problem – there may be a lot of things that are important to that character, but there’s only one that is the most important. And yes, people’s notions of what is most important can change over the course of an adventure, but if that’s what’s going on, then that is the central plot line. And yes, some writers can sit down and do that sort of change without thinking very far ahead…but if you are having trouble overshooting your endings, then you are not one of those writers, and you will have to decide what the central plot-problem is, and what it means to say that it is solved or resolved.

If the core of the problem is not being able to separate episodes, figuring out what the central problem of the book is should go a long way toward letting the writer see where the end is. If the navy commander’s central problem is that he’s never been recognized for his achievements, then the end of the book comes when the Admiral shakes his hand and says, “Good job; we’re giving you a promotion for winning that battle.” It ends there even if the writer knows perfectly well that the “promotion” has all sorts of problems and political strings attached, because those problems are new, they’re not the one this story is about.

If the core problem is getting distracted by shiny new plot ideas that could happen to the protagonist, once again, you start by deciding early on what the central problem of this book is. Every couple of chapters, you step back a little and check to make sure you are still heading toward the resolution of that problem. You don’t have to have a hard-and-fast ending in mind (many writers do, but it’s not a requirement), but you do have to know what “over and done with” means. You might have thought the hero and the villain would have a confrontation in a movie theater, but instead it happens on a beach – it isn’t the details that are important, it’s the fact that they have a confrontation and settle things once and for all.

If you’re a braider, you need to know what your central plot thread is, and then you have to pay attention to getting all your subplots to come out more-or-less even at about the same time as the central thread wraps up…and that means that at some point, you stop introducing new subplots and plot arcs. OK, if it really is going to be a long series, you may want to plant a few things for later, like the existence of the heroine’s estranged black sheep brother or ex-fiancé, but planting things is a lot lower-key and more subtle than introducing a subplot. Most of the time, what you are planting for the next book has little to do with this one, and it should ideally read that way – as minor background detail that the reader doesn’t need to remember, not as an intriguing mystery that they’ll want solved now. Also, whatever you are planting should, if possible, not make its first appearance in the last four or five chapters of the book. Not if you are going for subtle, anyway.

If you’re braiding several different characters’ plots…well, each of them has a central problem that is most important to them; your challenge is to see that all three or four of the characters resolve their central problem at more or less the same time. If one will take much longer to finish with than the others…maybe what you have is a main character and some subplots, rather than a true ensemble cast with braided plotlines.

February 4, 2014

Revenge, rehabilitation, and redemption

Some years back, I read a book on the history of the penal system – one of those random research things that pays off in unexpected ways. In this case, what struck me was the author’s summary of the history and theory behind law and punishment.

A quick summary goes something like this: The first and oldest theory of punishment was revenge, which was usually personal and extreme – blood feuds being an example. Eventually, Society took over getting revenge on wrongdoers. Gradually, the idea of getting revenge or payback for a wrong evolved into the idea of simply punishing the wrongdoer for doing it. Shortly thereafter, the idea of prevention came in – preventing future crimes by the wrongdoer and/or deterring other people from committing crimes and undergoing the same punishment. Last of all came the notion of rehabilitation – reeducating or reforming the criminal so he/she would become a productive citizen instead of a criminal.

This evolution has a lot of interesting implications for writers, especially for those of us who write historical or pseudo-historical fiction. The notion of rehabilitation was not around in the middle ages, not at all, and all too frequently, the way you prevented a repeat of a crime was by removing the criminal’s ability to do whatever it was – cutting off a pickpocket’s hand, for instance. That’s in places where the legal system was enlightened enough to consider this level of prevention; for lots of places, well, if you killed the guy, then he couldn’t do it again, and that’s prevention, isn’t it?

In addition to questions of historical accuracy in the legal system (and in various characters’ attitudes toward it), there’s the fact that the newer notions of punishment never fully replace the older ones. Once society and the legal system take over the job of punishing criminals, there’s a steady decline in the number of people seeking personal, over-the-top revenge on other individuals who steal their stuff, damage their property, kill their kinfolk, or otherwise commit some wrong against them, but that number never goes completely to zero. The number of people who want revenge, rather than equitable punishment (or, heaven forbid, rehabilitation), is a lot higher. And it remains so to this day, though it’s presumably not as bad as it was in Hammurabi’s time.

Which brings me to the other problem writers face: because there is this divergence of opinion in just what should be done about evildoers (do they deserve revenge, or punishment, or rehabilitation? And how do you prevent new crimes, if you’re not trying the rehabilitation thing?), the writer is never going to be able to please everyone when it comes to his/her treatment of the villains, most especially those villains whom the writer wishes to redeem. The closest you can get, I think, is to redeem the villain by having him sacrifice his life to save something/someone important – a child, the hero, the planet, the universe – and even then, there will be plenty of readers complaining that he didn’t suffer enough before he died.

This is one part of what makes it difficult to convincingly redeem a character who has done something wrong. The second part is that the redemption has to be in character for the character. Lois Bujold’s Sergeant Bothari was never going to be a fully normal, functional, moral human being; trying to redeem him by turning him into one would not have been true to the character. I’d argue that his struggle to rise above his limitations – and his occasional successes – make him in one sense a hero, though not the sort you’d want anyone to emulate in any other regard (and there are plenty of readers who disagree).

The third part of what makes redeeming a villain difficult is that real redemption is not easy, and there are certain things that the characters have to do (either right there on stage, or by strong implication through his/her actions) in order for readers to believe in it (and as I said, even then some readers will not accept it and will want revenge or greater punishment for the wrongs the villain has committed). Several times, I have seen writers make the mistake of skipping the process of redemption and going straight to the villain being accepted by the good guys as a former villain…and it never works. It especially doesn’t work if the villain almost immediately starts demanding things – forgiveness, love, generalship of the armies – because that always makes it look as if the “redemption” is just a trick so the villain can get what he/she wants (even if this is not supposed to be the case).

The steps the characters take have to do with the psychology of forgiveness and reconciliation. In short form, the villain has to admit what he did wrong (and that it was wrong – and preferably without making excuses), honestly say he’s sorry, promise not to do it again, and at least offer to make amends in some way (even if it isn’t really possible).

On the other side, the heroes have to say/show that they, too, think the villain has done wrong and that they are really hurt and angry about it, and they have to believe and accept (however reluctantly) that the villain won’t do it again. Whether they accept the redeemed villain’s offer of amends, reject it, or demand more is actually optional, so long as the villain is sincerely sorry and really means it when he offers amends.

In the case of the villain who knocks the hero out, shoves him into the heroine’s arms with a meaningful comment like “Try to think kindly of me,” and then takes the hero’s place on the suicide run that successfully destroys the alien invaders but kills the pilot, most of the steps on the villain’s side are implied by his actions. The not doing it again part is solid, since the villain will be dead; so is the making amends part (dying in someone’s place is a pretty good amends for most things). It’s the first two that aren’t always clear (the villain might still think he’s in the right, but he’s decided that the heroine’s happiness is more important and since she’s in love with the hero…well). Under the circumstances, though, most readers are willing to cut the guy some slack. The heroes don’t have to accept the live, reformed villain, so it’s a lot easier for them, too, to say that the guy did the right thing in the end, or died well, or whatever it is they would say under those conditions.

February 1, 2014

Finding and Feeding Critiquers

So LizV wants to know how to find critiquers in the first place, rightly noting that the last post I did has more to do with how you deal with them once you have them lined up.

The short answer is, you ask people. The longer answer…

You start with friends who you know read in your genre. Since they are friends, you presumably have a good idea whether you think their opinions will be worth listening to, and whether you will be able to listen to them. (Do not be too surprised if you are wrong; you never really know what a critiquer’s work will be like until you try them out.) If your friends don’t read, or don’t read in your genre, see if the library has a book club. Or troll the local science fiction/mystery club, if there is one, or ask around among fans at conventions. Just because they don’t write, doesn’t mean they can’t or won’t give you good comments.

However, giving good comments is work. It usually takes me a couple of days to do a thorough job on a short story. Novels usually take about a week, if they are given to me all at once, because if I’m doing a whole novel, there usually isn’t a lot of reason to do scene-by-scene analysis because the thing the author wants is macro-level comments on pacing and plot holes and believability and characterization – things that take place in large-scale arcs over several scenes or chapters.

Not everyone is willing or able to do this kind of work. If you start with friends, they may say “yes,” but never get past reading the story, or they may burn out quickly once they realize what they have let themselves in for. Even the ones who labor diligently will get cranky if they never get anything back. Dinner and a mention in the acknowledgements are kind of minimal, and never seemed to me to be enough repayment for what my reader-betas do. So you probably also want to find other writers in your genre who you can trade comments with. (If you are not willing to trade comments, you should probably only ask other would-be writers if you know each other and the other writer is aware of this quirk of yours. Trading is the primary currency of crit; food – dinner or at least snacks – is the secondary one.)

There are lots more ways to find other would-be writers than there used to be. Taking a class is not my favorite thing, but it puts you in contact with a bunch of folks who want to write, and most of the community ed writing classes I’ve taught have ended with half or more of the class forming writing groups. Libraries and bookstores often have bulletin boards with notices for meetings of “open” (i.e., anyone can come) crit groups, or people looking to form a new one. Conventions and workshops also provide lots of opportunity to meet other writers, and the Internet means that you can trade comments/crit without having to live particularly close or having to wait for a week between letters.

The Internet also has seen the rise of on-line critique communities and circles. Like open crit groups, some people have really good luck with them and some do not. It’s not predictable; you just have to try it and see if it works, and if it doesn’t, go somewhere else and try that. And you can always ask people who have been part of a useful discussion in comment threads. I got some lovely useful comments from a historian once who I emailed based on her comments in an on-line forum on historical turning points.

Finding/developing good critiquers is not easy; they’re not going to just drop into your lap. If you have smart friends who read in your genre, your best bet is to find some who are willing (i.e., ask them and they say yes) and train them. Ditto for fellow writers. I personally find group interactions especially useful; I get a lot out of listening to everyone else discuss what’s working or not, and a lot of what I know about critiquing, I learned by example, from watching other writers critique me and each other. If you have a couple of non-writer friends who are doing crit for you, think about asking two or three of them over/out for dinner to discuss what they liked and didn’t about your book.

When you ask someone new to comment on your work, make it clear that this is a trial run for both of you, a one-time deal that may or may not be renewed, no explanations necessary. You want to have an out in case the commentor turns out to be an unsalvageable dud; they need to know that it is OK to say “This was fun, but it was a lot more work than I expected and I don’t have time to do it again.” It is also important to let the critique know that you are not going to rewrite the story to his/her specifications. If they don’t like it, fine; if they’d have done something differently, fine; if they were more interested in the tiny subplot or a minor character than in your protagonist and her woes, fine; but they shouldn’t be disappointed if nothing changes in the final version. By the same token, if they hit the nail on the head, they don’t get co-authorship when you promote the minor character to major viewpoint.

I’ve been through three or four completely new and different crit groups over the years, as well as having an ever-changing set of non-writer beta readers. I am always looking for new people, because finding good ones is a slow process. It’s particularly tricky at the beginning, when you are finding maybe one or two people every couple of years, because the temptation is to overload the one good critique partner you have found, which will almost certainly burn them out before you have a chance to collect enough others to share the load.

If the first round of comments you get from someone is annoying, if they are insistent that you rewrite according to their opinions, if they make you feel bad about your work and yourself, then there are two possibilities: either they are most definitely not the critique for you, or you are the kind of person who does not handle peer crit well and who therefore should not push to get any. Thank them and move on. If you get the same result from the second and/or third person, evidence is accumulating in favor of you not being the sort who can handle peer critique. This is only a problem if you insist on continuing to get some. It is perfectly all right to go it alone; you will probably have to work harder at analyzing and correcting your own work, but you can make that easier by volunteering to give crit in exchange for dinner. This will let you practice analyzing on other people’s work, and trust me, you will learn a lot from it.

January 28, 2014

What I have been up to

I am back, after eight days in Beijing and Shanghai, plus two on the plane, plus another four in San Francisco on the way there (because my sister wasn’t going to San Francisco without eating at Fisherman’s Wharf and it sort of spiraled from there). I still have my traditional Souvenir Cold, complicated by a massive case of jet lag, which means I haven’t unpacked and have been mostly being a cat napping place for the last several days.

To preemptively answer a few questions: No, it wasn’t a business trip. My walking buddy, who is a demon bargain-hunter, found an 8-day package tour that was too good a deal to pass up; my sister and my father decided to join us. (When I told one of my crit group members I was going to have to miss the monthly meet-up because I was going to China, she looked at me and said, “You always have the best excuses …”)

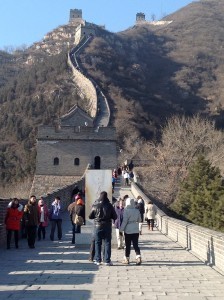

We climbed around on the Great Wall, walked through Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City, saw the pandas and the Temple of Heaven, had tea in the old city, went to a silk factory, and assorted other things, most of which involved shopping. It was a very busy, not to say hectic, eight days. I got the first six inches of the silk shawl knitting project done (I think; I’ve had to rip it at least seven times already, so I hope this is the final try) on the airplane.

The weather was good the whole time – that is, sunny and not too cold (given that we’d come from -17 F, our notions of “not too cold” were a lot more elastic than most of the rest of the tourfolks’). The air pollution gave most of us sore throats by day 7; it reminded me of Los Angeles when I visited as a kid in the early 1960s, before they put catalytic converters on cars and took the lead out of the gas and did various other air quality things.

My sister took most of the pictures with her good camera; I just have a couple on my iPad. For example:

This needs no label. I took it on day one, because Mao’s picture on the gate into the Forbidden City is the iconic I-have-been-to-China picture, and I wanted one that I took myself (in addition to the much better ones that I’m going to get from my sister eventually). I didn’t touch it up, so you can see the pollution haze in the air.

This also needs no label. Second day, outside Beijing. I did not climb to the top, because I have a trick knee and the steps got to being almost knee-high in the steep parts. I did make it to the second tower, which is the pointed roof behind the first squared-off tower. It looks as if it’s part of the front tower, but it’s actually across a wide platform and up another bunch of steps. The one that looks like the second one, about halfway up that long steep climb, is really the third tower.

I did not get any writing done on the trip, not even a trip journal. This is unusual for me, but the combination of the pace and the time change was a bit more than I could manage. Which just demonstrates how much one’s creativity depends on both one’s circumstances and one’s physical condition. A lot of the time at home, I tend to blame my lack of productivity on lack of time, when it’s really lack of sleep and/or lack of energy due to running around at such a frantic pace that when I do have a couple of free hours, I veg instead of writing.

And that’s about as much on writing as you’re going to get today. By Sunday, I should be less foggy-headed and able to address Liz’s question about how to find people to crit your work (at least, I think that’s what she meant). See you then!

January 21, 2014

Regular service will resume soon

Just a note from the webmaster to apologize for the lack of post today. Regular service will resume Sunday.