Michael Greger's Blog, page 2

October 16, 2025

Lose Weight with Cumin and Saffron?

The spice cumin can work as well as orlistat, the “anal leakage” obesity drug.

In my video Friday Favorites: Benefits of Black Cumin for Weight Loss, I discussed how a total of 17 randomized controlled trials showed that the simple spice could reduce cholesterol and triglyceride levels. And its side effects? A weight-loss effect.

Saffron is another spice found to be effective for treating a major cause of suffering—depression, in this study, with a side effect of decreased appetite. Indeed, when put to the test in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, saffron was found to lead to significant weight loss, five pounds more than placebo, and an extra inch off the waist in eight weeks. The dose of saffron used in the study was the equivalent of drinking a cup of tea made from a large pinch of saffron threads.

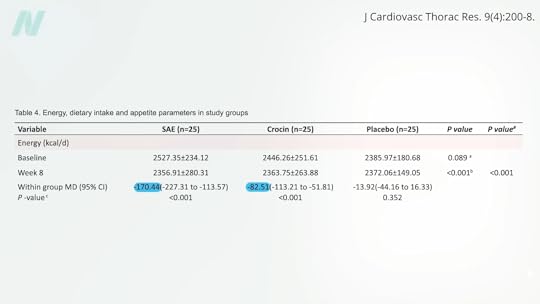

Suspecting the active ingredient might be crocin, the pigment in saffron that accounts for its crimson color, as shown here and at 0:59 in my video Friday Favorites: Benefits of Cumin and Saffron for Weight Loss, researchers also tried giving people just the purified pigment.

That also led to weight loss, but it didn’t do as well as the full saffron extract and only beat the placebo by two pounds and half an inch off the waist. The mechanism appeared to be appetite suppression, as the crocin group ended up averaging about 80 fewer calories a day, whereas the full saffron group consumed an average of 170 fewer daily calories, as you can see below and at 1:21 in my video.

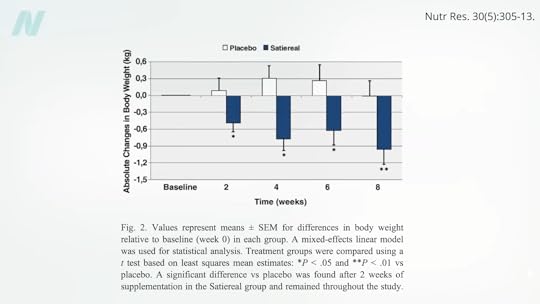

A similar study looked specifically at snacking frequency. The researchers thought that the mood-boosting effects of saffron might cut down on stress-related eating. Indeed, eight weeks of a saffron extract halved snack intake, compared to a placebo. There was also a slight but statistically significant weight loss of about two pounds, as you can see here and at 1:41 in my video, which is pretty remarkable, given that tiny doses were utilized—about 100 milligrams, which is equivalent to about an eighth of a teaspoon of the spice.

The problem is that saffron is the most expensive spice in the world. It’s composed of delicate threads sticking out of the saffron crocus flower. Each flower produces only a few threads, so about 50,000 flowers are needed to make a single pound of spice. That’s enough flowers to cover a football field. So, that pinch of saffron could cost a dollar a day.

That’s why, in my 21 Tweaks to accelerate weight loss in How Not to Diet, I include black cumin, instead of saffron, as you can see here and at 2:30 in my video. And, at a quarter teaspoon a day, the daily dose of black cumin would only cost three cents.

What about just regular cumin? Used in cuisines around the world from Tex-Mex to South Asian, cumin is the second most popular spice on Earth after black pepper. It is one of the oldest cultivated plants with a range of purported medicinal uses, but only recently has it been put to the test for weight loss. Those randomized to a half teaspoon at both lunch and dinner over three months lost about four more pounds and an extra inch off their waist. The spice was found to be comparable to the obesity drug known as orlistat.

If you remember, orlistat is the “anal leakage” drug sold under the brand names Alli and Xenical. The drug company apparently prefers the term “faecal spotting” to describe the rectal discharge it causes, though. The drug company’s website offered some helpful tips, including: “It’s probably a smart idea to wear dark pants, and bring a change of clothes with you to work.” You know, just in case their drug causes you to poop in your pants at the office.

I think I’ll stick with the cumin, thank you very much.

Doctor’s Note

The video on black cumin that I mentioned is Friday Favorites: Benefits of Black Cumin Seed (Nigella Sativa) for Weight Loss.

My other videos on saffron are in the related posts below.

For an in-depth dive into weight loss, see my book How Not to Diet.

October 14, 2025

Med Students Must Stop Performing Pelvic Exams on Unconscious Women Without Their Consent

Please note: This blog contains descriptions of sexual assault.

“Recent reports of medical students performing pelvic exams for training purposes on anesthetized women without their consent”—or their knowledge—“have produced a firestorm of controversy and calls for greater regulation.” However, that “burst of public outcry” was in the mid-1990s. California was the first state to make the practice illegal, but the “early gains quickly petered out.”

As I discuss in my video Ending the Hidden Practice of Pelvic Exams on Unconscious Women Without Their Consent, “This practice, common since the late 1800s, was largely unchallenged until a 2003 study reported that 90 percent of medical students who completed obstetrics and gynecology (ob-gyn) rotations at four Philadelphia-area medical schools performed pelvic exams on anesthetized women for educational purposes.” (A subsequent study found the percentage to be lower than that in other areas of the country.) The bottom line? “Pelvic Exams Done on Anesthetized Women Without Consent: Still Happening.” How can this continue into 2025? Medical ethicists have called such practices “immoral and indefensible.” “At the end of the day, this is a practice that should come to an abrupt and immediate halt.” Some schools vowed they’d end the practice, but, unfortunately, these early victories quickly stalled. At the same time, a handful of schools revamped their policies, an equal number of hospitals and medical schools publicly dug in, defending the practice.

The Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics wrote: “As medical educators, we must balance our obligation to develop the next generation of physicians with women’s freedom to decide from whom they receive treatment and what aspects of their care are performed by learners.” “Some especially blunt teaching faculty contend that ‘public’ patients”—those without health insurance—“owe it to the facility and society to participate since they receive free or subsidized care.” Regulations to curb this practice are said to be “placing inappropriate and unnecessary barriers in the way of medical students who need to learn fundamental medical skills” and therefore “should be resisted.” Unsurprisingly, medical students still perform pelvic exams on anesthetized women.

Professional medical societies have given lip service to the concept of asking for explicit consent, but despite the recommendations, “evidence…suggests that the practice is alive and well.” And the “unauthorized use of women is not a localized phenomenon confined to a handful of errant medical schools,” a few bad med school apples, but an international problem.

Even with the emergence of the #MeToo movement and even after Larry Nasser, the infamous USA gymnastics doctor, was sentenced to 40 to 175 years in prison for touching women’s genitalia without their consent, “there are still women who are being used as teaching subjects for these exams without their permission, without their consent.”

A 2020 update from Yale’s Center for Bioethics was entitled: “A Pot Ignored Boils On: Sustained Calls for Explicit Consent of Intimate Medical Exams.” It reads, “Over the last 30 years, several parties—both within and external to medicine—have increasingly voiced opposition to these exams. Arguments from medical associations, legal scholars, ethicists, nurses, and some physicians have not compelled meaningful institutional change.” Yes, there is the lip service paid by medical associations recommending bans on pelvic exams without consent, but those statements are “advisory and incomplete. Associations simply do not have the capacity to compel systemic change, as evidenced by institutions’ inaction.” In response to the medical profession’s inability to police itself, many states have passed legislation to protect patients from this practice.

But, of course, if you are anesthetized, how would you even know if medical students are lining up or not? “Teaching hospitals take patients who are in the worst position to know what’s occurring—they are unconscious—and use them in ways that leave no physical signs and are often undocumented in the patients’ medical records.” So, when the media loses interest, as it has decade after decade, “what incentive is there for teaching faculty or hospitals to voluntarily change?” Perhaps, “when physicians start being threatened with litigation, they’ll start obtaining informed consent.” As one commentator wrote, “Hospital administrators who allow medical students in their facilities to perform pelvic examinations on unconsenting anesthetized women ought to consult with their legal counsel concerning the definition of rape in their jurisdiction.”

“The solution is simple: Just ask.” Ask women for permission. It’s their body, their choice. “But recent experience has shown that meaningful and complete hospital-by-hospital change is unlikely to come until a hospital or doctor pays a substantial award [in some lawsuit] for this error in ethical judgment. We believe that day is coming soon, lest that ignored pot finally boil over.

“Some defend it as harmless and say asking for consent would make it more likely that patients would say no, denying students a crucial part of their training.” When I first wrote about this practice more than 20 years ago in my book Heart Failure about my time in medical school, I talked about how I had gotten the same comments from my classmates: “A well-then-how-are-we-going-to-learn response. To even present such a question is to lose a bit of one’s humanity. The answer, of course, is we should learn from women who give their consent! And to do that—God forbid—we might actually have to first establish a relationship with the patient, a trust—talk to them even. We may have to treat them like human beings.”

It’s unconscionable that medical students are legally allowed to practice pelvic exams on anesthetized women without their consent. Even if you live in one of the states where this practice is technically illegal, how do you know the law will be respected once you’re unconscious? Maybe medical students should wear bodycams.

If you missed the related video, see Medical Students Practice Pelvic Exams on Anesthetized Women Without Their Consent.

October 9, 2025

Celebrating Food and National Hispanic Heritage Month with Ale Graf

As someone who creates Mexican dishes with a plant-based twist, how is food an important part of your culture and how you share your culture with others?

Food is so much more than nourishment—it’s how we love, connect, and remember who we are. For Mexicans, food is truly part of our DNA. From ancient times, when our ancestors offered food to the gods, to modern-day sobremesas with family and friends, sharing food is how we express love. I grew up surrounded by women who talked about recipes the way others talk about dreams. My mother, grandmother, and aunts were always planning the next meal or discovering a new dish. Now I do the same with my siblings. Even though my food today is mostly plant-based, its essence is the same: to bring people together. Through my recipes, I want to recreate that sense of belonging, of always having enough to share and always leaving room for one more at the table. That’s what comemos means to me. It’s not about nostalgia; it’s about showing what being Mexican really looks and tastes like today.

When did you start cooking and developing your own recipes? How do you educate people about making beautiful Mexican dishes using plant-based ingredients? Are people ever surprised to learn your recipes are plant-based?

I started 23 years ago, right after my son was diagnosed with a dairy allergy. That moment changed everything. I had to relearn how to cook. I leaned into spices, explored new vegetables, and discovered different cooking methods. What began as a necessity quickly turned into a passion. I even enrolled in an online course to get certified as a plant-based cook. As my kids grew, so did my curiosity and creativity in the kitchen. Educating others has always been fun for me. I don’t lead with “plant-based” or “vegan”; I lead with flavor. I’ll serve someone a bowl of bean soup, and, after they’ve devoured it, I’ll smile and say, “Congrats, you just had your first vegan meal.” It’s always a surprise for them, and that’s the magic— showing how beautiful, satisfying, and deeply Mexican plant-based food can be.

What are some plant-based ingredients and/or vegan dishes that you’d like to highlight as part of Mexican food traditions? Anything you’d especially like people to know about these foods?

Masa, hands down. It’s the heart of so many beloved Mexican dishes—sopes, huaraches, tlacoyos—and it’s naturally plant-based. What I love most is how versatile it is. You can shape masa into antojitos, but you can also use it to make dumplings and cakes, or get creative and reinterpret global dishes with a Mexican twist. Take a good sope and layer it with mashed potatoes or creamy refried beans, top with salsa, guacamole, shredded lettuce, pickled onions—whatever you love. That’s the beauty of Mexican food; it’s endlessly customizable. You can set up a spread with all kinds of toppings and let everyone build their own plate. It’s not just delicious. It’s inclusive, joyful, and rooted in sharing.

What do you envision as the way forward to encourage people to eat more fruits and vegetables and return to traditional Hispanic eating patterns?

I think the real barrier is the labels and the absolutes. When we frame eating habits as all-or-nothing, people tune out. But if we shift the focus to just one healthy, vibrant meal at a time—one that’s full of colorful fruits and vegetables that add texture, flavor, and joy—then it feels more approachable and exciting. Traditional Hispanic food already celebrates plant-forward ingredients like chiles, tomatoes, squash, beans, and corn. If we bring those foods back to the center of the plate in a way that feels natural, not forced, people will reconnect with them. It’s about showing how beautiful and delicious these meals can be, not preaching about what they “should” eat.

What does National Hispanic Heritage Month mean to you?

To me, National Hispanic Heritage Month is a time to learn, grow, and open our hearts to other cultures. It’s a reminder that the Hispanic community is not monolithic. We come from so many different countries, regions, and traditions, each with its own stories, flavors, and rhythms. This month is about recognizing that richness and also embracing how much we can learn from one another. It’s a time to celebrate our shared values and our differences, and, ultimately, a time to shine a light on how much more we have in common than we often realize.

Please tell us a little bit about your work and career.

I’m a published cookbook author and food blogger passionate about creating healthy, plant-forward meals, some Mexican, that bring people together. My journey started 23 years ago when my son was diagnosed with a dairy allergy. That experience led me to explore plant-based cooking, earn a certification, and eventually launch my blog Piloncillo & Vainilla in 2013, followed by Ale Cooks in English.

I live in Houston with my family, where I continue to cook, create, and celebrate food as the heart of connection.

Hibiscus Chamoy

Originally published here.

Ingredients

2 cups hydrated hibiscus flowers

1 cup dried cherries or dried cranberries

3 tablespoons ground chile ancho subs or any other chili powder (or to taste)

1 tablespoon date syrup or date sugar

1 cup water or hibiscus water

¼ cup lime juice (or to taste)

Pinch of Tajin (optional)

Instructions

Simmer the Ingredients: Start by adding the hibiscus flowers, dried fruit, chiles, and date syrup or date sugar to a blender, then add 1 cup of boiling water. (You can use a glass or stainless-steel bowl.)Blend to Perfection: Blend until smooth. If needed, add ¼ cup water to adjust the consistency.Season and Adjust: Finish with the lime juice, and add a pinch of Tajin if you’d like.Store and Serve: Pour into a clean jar, seal tightly, and refrigerate. It keeps well for up to a month in the fridge, so you’ll have plenty of time to experiment with it on different dishes!You can find Ale on her blog alecooks.com and piloncilloyvainilla.com, Instagram, Facebook, and Pinterest.

October 7, 2025

“An Outrageous Assault”: Pelvic Exams by Med Students on Anesthetized Women

Please note: This blog contains descriptions of sexual assault.

From Heart Failure, a book I wrote about my time at Tufts University School of Medicine: “I am all gloved up, fifth in line. At Tufts, medical students—particularly male students—practice pelvic exams on anesthetized women without their consent and without their knowledge. Women come in for surgery and, once they’re asleep, we all gather around; line forms to the left…We learn more than examination skills. Taking advantage of the woman’s vulnerability—as she lay naked on a table unconscious—we learn that patients are tools to exploit for our education.”

Using female patients to teach pelvic exams without their consent or knowledge remains “a dirty little secret about medical schools.” It is an “age-old” practice that continues to this day in med schools around the world. It’s been referred to as “the ‘vending machine’ model of pelvic exams, in which medical students line up to take their turn…” “Only it’s not a vending machine; it’s a woman’s vagina.”

It’s been called “an outrageous assault upon the dignity and autonomy of the patient…The practice shows a lack of respect for these patients as persons, revealing a moral insensitivity and a misuse of power.” Indeed, “it is yet another example of the way in which physicians abuse their power and have shown themselves unwilling to police themselves in matters of ethics, especially with regard to female patients.” Said a residency-program director at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, “I don’t think any of us even think about it. It’s just so standard as to how you train medical students.”

What happened when this practice came to light in New Zealand? The chair of the New Zealand Medical Association got on television and said: “‘Until recently it wasn’t an issue…I’m very sorry that women feel they’ve been assaulted and violated in this way. That was never our intention.’ He had no idea then, asked the [TV] presenter, that women might object? ‘All I can say is that there have been no objections…’ ‘Could the reason be,’ asked the interviewer logically, “that it’s very hard for an anesthetized woman to know what’s going on?’”

The practice has been defended publicly by many medical schools and hospitals, contending “this touching is entirely appropriate and clearly falls well within the patient’s ‘implied consent’ to carry out the operation.” After all, “patients are aware they are entering a teaching hospital and therefore know that trainees will be actively participating in their care.” However, “researchers have found that many patients do not know when they have interacted with medical students, or even whether they are in a teaching hospital.” How can this be? “Deliberate lies and deception.”

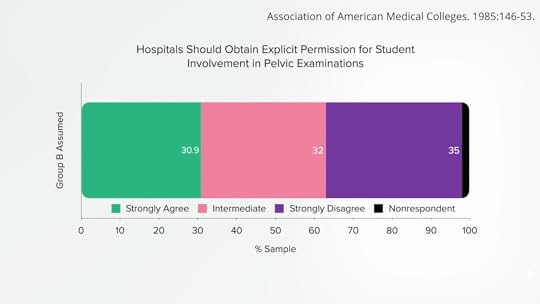

“A survey of medical students found that 100% of them had been introduced to patients as ‘doctor’ by members of the clinical team,” and, as they go through training, there is, as a journal article is titled, an “Erosion in Medical Students’ Attitudes About Telling Patients They Are Students.” “Additionally, as medical students complete their clinical years of training, their sense of responsibility to inform patients that they are students is found to decrease,” especially if there is an opportunity to perform an invasive procedure. That may be why medical students seem to develop a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy when it comes to seeking consent for pelvic examinations on anesthetized patients. More than a third of 1,600 medical students surveyed across the country strongly disagreed with the statement “Hospitals should obtain explicit permission for student involvement in pelvic exams,” as seen below and at 4:03 of my video Medical Students Practice Pelvic Exams on Anesthetized Women Without Their Consent.

After all, doctors “argue that performing a pelvic examination is no more intimate than placing one’s hands inside an abdomen during general surgery or attempting to intubate a patient” and assert that sticking your fingers in a woman’s vagina is “just as intimate” as an ophthalmologist looking into the back of your eye; any claim to the contrary is just “another attempt to justify the obsession with political correctness.” Said one medical school professor, “Personally, I would prefer to see a new generation of well-trained doctors…rather than a nation of women whose vaginas are protected from battery by medical students.”

The national survey concluded: “Patients admitted to teaching hospitals do not, however, by the mere act of admission relinquish their rights as human beings to have ultimate control over their own body and to be involved in decisions concerning their health care.”

Is it possible that women just don’t care? Studies show that up to 100% of women asked said they would want to know that vaginal exams were being performed by medical students. Since patients care deeply about being asked, why can’t we at least ask their permission? “We can’t ask women,” the medical school faculty replied. “If we do, they might say no.”

It’s jaw-dropping to me that I’m still trying to expose this practice more than 20 years after I first wrote about it. What’s to be done? Ending the Hidden Practice of Pelvic Exams on Unconscious Women Without Their Consent.

October 2, 2025

A Longer Life on Statins?

What are the pros and cons of relative risk, absolute risk, number needed to treat, and average postponement of death when taking cholesterol-lowering statin drugs?

In response to the charge that describing the benefits of statin drugs only in terms of relative risk reduction is a “statistical deception” created to give the appearance that statins are more effective than they really are, it was pointed out that describing things in terms of absolute risk reduction or number needed to treat can depend on the duration of the study.

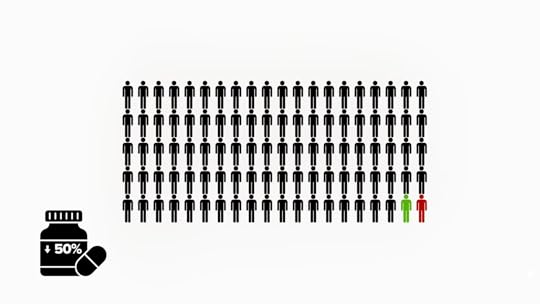

For example, let’s say a disease has a 2% chance of killing you every year, but some drug cuts that risk by 50%. That sounds amazing, until you realize that, at the end of a year, your risk will only have fallen from 2% to 1%, so the absolute reduction of risk is only 1%. If a hundred people were treated with the drug, instead of two people dying, one person would die, so a hundred people would have to be treated to save one life, as shown below and at 1:01 in my video How Much Longer Do You Live on Statins?.

But there’s about a 99% chance that taking the drug all year would have no effect either way. So, to say the drug cuts the risk of dying by 50% seems like an overstatement. But think about it: Benefits accrue over time. If there’s a 2% chance of dying every year, year after year, after a few decades, the majority of those who refused the drug would be dead, whereas the majority who took the drug would be alive. So, yes, perhaps during the first year on the drug, there was only about a 1% chance it would be life-saving, but, eventually, you could end up with a decent chance the drug would save your life after all.

“This is actually the very reason why the usage of relative risk makes sense…” Absolute risk changes depending on the time frame being discussed, but with relative risk, you know that whatever risk you have, you can cut it in half by taking the drug. On average, statins only cut the risk of a cardiovascular “event” by 25%, but since cardiovascular disease is the number one killer of men and women, if you’re unwilling to change your diet, that’s a powerful argument in favor of taking these kinds of drugs. You can see the same kind of dependency on trial duration, looking at the “postponement of death” by taking a statin. How much longer might you live if you take statins?

The average postponement of death has some advantages over other statistics because it may offer “a better intuitive understanding among lay persons,” whereas a stat like a number needed to treat has more of a win-or-lose “lottery-like” quality. So, when a statin drug prevents, say, one heart attack out of a hundred people treated over five years, it’s not as though the other 99 completely lost out. Their cholesterol also dropped, and their heart disease progression presumably slowed down, too, just not enough to catch a heart attack within that narrow time frame.

So, what’s the effect of statins on average survival? According to an early estimate, if you put all the randomized trials together, the average postponement of death was calculated at maybe three or four days. Three or four days? Who would take a drug every day for years just to live a few more days? Well, let’s try to put that into context. Three or four days is comparable to the gains in life expectancy from other medical interventions. For example, it’s nearly identical to what you’d get from “highly effective childhood vaccines.” Because vaccines have been so effective in wiping out infectious diseases, these days, they only add an average of three extra days to a child’s life. But, of course, “those whose deaths are averted gain virtually their whole lifetimes.” That’s why we vaccinate. It just seems like such a small average benefit because it gets distributed over the many millions of kids who get the vaccine. Is that the same with statins?

An updated estimate was published in 2019, which explained that the prior estimate of three or four days was plagued by “important weaknesses,” and the actual average postponement of death was actually ten days. Headline writers went giddy from these data, but what they didn’t understand was that this was only for the duration of the trial. So, if your life expectancy is only five years, then, yes, statins may increase your lifespan by only ten days, but statins are meant to be taken a lot longer than five years. What you want to know is how much longer you might get to live if you stick with the drugs your whole life.

In that case, it isn’t an extra ten days, but living up to ten extra years. Taking statins can enable you to live years longer. That’s because, for every millimole per liter you lower your bad LDL cholesterol, you may live three years longer and maybe even six more years, depending on which study you’re reading. A millimole in U.S. units is 39 points. Drop your LDL cholesterol by about 39 points, and you could live years longer. Exercise your whole life, and you may only increase your lifespan by six months, and stopping smoking may net you nine months. But if you drop your LDL cholesterol by about 39 points, you could live years longer. You can accomplish that by taking drugs, or you can achieve that within just two weeks of eating a diet packed with fruits, vegetables, and nuts, as seen here and at 5:30 in my video.

Want to know what’s better than drugs? “Something important and fundamental has been lost in the controversy around this broad expansion of statin therapy.…It is imperative that physicians (and drug labels) inform patients that not only their lipid [cholesterol] levels but also their cardiovascular risk can be reduced substantially by adoption of a plant-based dietary pattern, and without drugs. Dietary modifications for cardiovascular risk reduction, including plant-based diets, have been shown to improve not only lipid status, but also obesity, hypertension, systemic inflammation, insulin sensitivity, oxidative stress, endothelial function, thrombosis, and cardiovascular event risk…The importance of this [plant-based] approach is magnified when one considers that, in contrast to statins, the ‘side effects’ of plant-based diets—weight loss, more energy, and improved quality of life—are beneficial.”

September 30, 2025

The Real Benefits of Statins and Their Side Effects

A Mayo Clinic visualization tool can help you decide if cholesterol-lowering statin drugs are right for you.

“Physicians have a duty to inform their patients about the risks and benefits of the interventions available to them. However, physicians rarely communicate with methods that convey absolute information, such as numbers needed to treat, numbers needed to harm, or prolongation of life, despite patients wanting this information.” That is, for example, how many people are actually helped by a particular drug, how many are actually hurt by it, or how much longer the drug will enable you to live, respectively.

If doctors inform patients only about the relative risk reduction—for example, telling them a pill will cut their risk of heart attacks by 34 percent—nine out of ten agree to take it. However, give them the same information framed as absolute risk reduction—“1.4% fewer patients had heart attacks”—then those agreeing to take the drug drops to only four out of ten. And, if they use the number needed to treat, only three in ten patients would agree to take the pill. So, if you’re a doctor and you really want your patient to take the drug, which statistic are you going to use?

The use of relative risk stats to inflate the benefits and absolute risk stats to downplay any side effects has been referred to as “statistical deception.” To see how one might spin a study to accomplish this, let’s look at an example. As you can see below and at 1:49 in my video, The True Benefits vs. Side Effects of Statins, there is a significantly lower risk of the incidence of heart attack over five years in study participants randomized to a placebo compared to those getting the drug. If you wanted statins to sound good, you’d use the relative risk reduction (24 percent lower risk). If you wanted statins to sound bad, you’d use the absolute risk reduction (3 percent fewer heart attacks).

Then you could flip it for side effects. For example, the researchers found that 0.3 percent (1 out of 290 women in the placebo group) got breast cancer over five years, compared to 4.1 percent (12 out of 286) in the statin group. So, a pro-statin spin might be a 24 percent drop in heart attack risk and only 3.8 percent more breast cancers, whereas an anti-statin spin might be only 3 percent fewer heart attacks compared to a 1,267 percent higher risk of breast cancer. Both portrayals are technically true, but you can see how easily you could manipulate people if you picked and chose how you were presenting the risks and benefits. So, ideally, you’d use both the relative risk reduction stat and the absolute risk reduction stat.

In terms of benefits, when you compile many statin trials, it looks like the relative risk reduction is 25 percent. So, if your ten-year risk of a heart attack or stroke is 5 percent, then taking a statin could lower that from 5 percent to 3.75 percent, for an absolute risk reduction of 1.25 percent, or a number needed to treat of 80, meaning there’s about a 1 in 80 chance that you’d avoid a heart attack or stroke by taking the drug for the next ten years. As you can see, as your baseline risk gets higher and higher, even though you have that same 25 percent risk reduction, your absolute risk reduction gets bigger and bigger. And, with a 20 percent baseline risk, that means you have a 1 in 20 chance of avoiding a heart attack or stroke over the subsequent decade if you take the drug, as seen below and at 3:31 in my video.

So, those are the benefits. In terms of risk, that breast cancer finding appears to be a fluke. Put together all the studies, and “there was no association between use of statins and the risk of cancer.” In terms of muscle problems, estimates of risk range from approximately 1 in 1,000 to closer to 1 in 50.

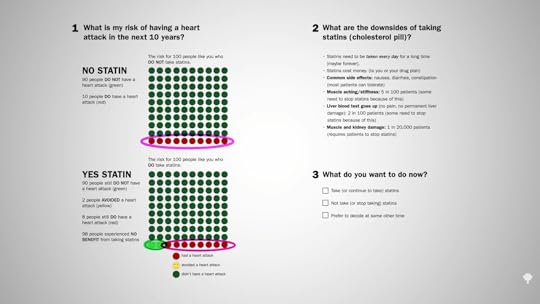

If all those numbers just blur together, the Mayo Clinic developed a great visualization tool, seen below and at 4:39 in my video.

For those at average risk, 10 people out of 100 who do not take a statin may have a heart attack over the next ten years. If, however, all 100 people took a statin every day for those ten years, 8 would still have a heart attack, but 2 would be spared, so there’s about a 1 in 50 chance that taking the drug would help avert a heart attack over the next decade. What are the downsides? The cost and inconvenience of taking a pill every day, which can cause some gastrointestinal side effects, muscle aching, and stiffness in about 5 percent, reversible liver inflammation in 2 percent, and more serious damage in perhaps 1 in 20,000 patients.

Note that the two happy faces in the bottom left row of the YES STATIN chart represent heart attacks averted, not lives saved. The chance that a few years of statins will actually save your life if you have no known heart disease is about 1 in 250.

If you want a more personalized approach, the Mayo Clinic has an interactive tool that lets you calculate your ten-year risk. You can get there directly by going to bit.ly/statindecision.

September 25, 2025

Are We Being Misled About the Benefits and Risks of Statins?

What is the dirty little secret of drugs for lifestyle diseases?

Drug companies go out of their way—in direct-to-consumer ads, for example—to “present pharmaceutical drugs as a preferred solution to cholesterol management while downplaying lifestyle change.” You see this echoed in the medical literature, as in this editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association: “Despite decades of exhortation for improvement, the high prevalence of poor lifestyle behaviors leading to elevated cardiovascular disease risk factors persists, with myocardial infarction [heart attack] and stroke remaining the leading causes of death in the United States. Clearly, many more adults could benefit from…statins for primary prevention.” Do we really need to put more people on drugs? A reply was published in the British Medical Journal: “Once again, doctors are implored to ‘get real’—stop hoping that efforts to help their patients and communities adopt healthy lifestyle habits will succeed, and start prescribing more statins. This is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Note that the author of these comments [the pro-statin editorial] disclosed receipt of funding from 11 drug companies, at least four of which produce or are developing new classes of cholesterol-lowering agents,” which make billions of dollars a year in annual sales.

Every time the cholesterol guidelines expand the number of people eligible for statins, they’re decried as a “big kiss to big pharma.” This is understandable, since the majority of guideline panel members “had industry ties,” financial conflicts of interest. But these days, all the major statins are off-patent, so there are inexpensive generic versions. For example, the safest, most effective statin is generic Lipitor, sold as atorvastatin for as little as a few dollars a month. So, nowadays, the cholesterol guidelines are not necessarily “part of an industry plot.”

“The US way of life is the problem, not the guidelines…” The reason so many people are candidates for cholesterol- and blood-pressure-lowering medications is that so many people are taking such terrible care of themselves. The bottom line is that “individuals must take more responsibility for their own health behaviors.” What if you are unwilling or unable to improve your diet and make lifestyle changes to bring down that risk? If your ten-year risk of having a heart attack is 7.5 percent or more and going to stay that way, then the benefits of taking a statin drug likely outweigh the risk. That’s really for you to decide, though. It’s your body, your choice.

“Whether or not the overall benefit-harm balance justifies the use of a medication for an individual patient cannot be determined by a guidelines committee, a health care system, or even the attending physician. Instead, it is the individual patient who has a fundamental right to decide whether or not taking a drug is worthwhile.” This was recognized by some of medicine’s “historical luminaries such as Hippocrates,” but “only in recent decades has the medical profession begun to shift from a paternalistic ‘doctor knows best’ stance towards one explicitly endorsing patient-centered, evidence-based, shared decision-making.” One of the problems with communicating statin evidence to support this shared decision-making is that most doctors “have a poor understanding of concepts of risk and probability and…increasing exposure to statistics in undergraduate and postgraduate education hasn’t made much difference.” But that understanding is critical for preventive medicine. When doctors offer a cholesterol-lowering drug, “they’re doing something quite different from treating a patient who has sought help because she is sick. They’re not so much doctors as life insurance salespeople, peddling deferred benefits in exchange for a small (but certainly not negligible) ongoing inconvenience and cost. In this new kind of medicine, not understanding risk is the equivalent of not knowing about the circulation of the blood or basic anatomy. So, let’s dive in and see exactly what’s at stake.

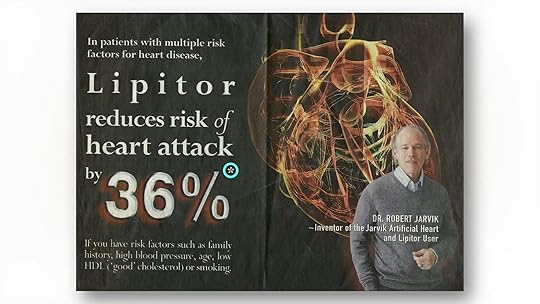

Below and at 3:55 in my video Are Doctors Misleading Patients About Statin Risks and Benefits? is an ad for Lipitor. When drug companies say a statin reduces the risk of a heart attack by 36 percent, that’s the relative risk.

If you follow the asterisk I’ve circled after the “36%” in the ad, you can see how they came up with that. I’ve included it here and at 3:56 in my video. In a large clinical study, 3 percent of patients not taking the statin had a heart attack within a certain amount of time, compared to 2 percent of patients who did take the drug. So, the drug dropped heart attack risk from 3 percent to 2 percent; that’s about a one-third drop, hence the 36 percent reduced relative risk statistic. But another way to look at going from 3 percent to 2 percent is that the absolute risk only dropped by 1 percent. So, in effect, “your chance to avoid a nonfatal heart attack during the next 2 years is about 97% without treatment, but you can increase it to about 98% by taking a Crestor [a statin] every day.” Another way to say that is that you’d have to treat 100 people with the drug to prevent a single heart attack. That statistic may shock a lot of people.

If you ask patients what they’ve been led to believe, they don’t think the chance of avoiding a heart attack within a few years on statins is 1 in 100, but 1 in 2. “On average, it was believed that most patients (53.1%) using statins would avoid a heart attack after statin treatment for 5 years.” Most patients, not just 1 percent of patients. And this “disparity between actual and expected effect could be viewed as a dilemma. On the one hand, it is not ethically acceptable for caregivers to deliberately support and maintain illusive treatment expectations by patients.” We cannot mislead people into thinking a drug works better than it really does, but on the other hand, how else are we going to get people to take their pills?

When asked, people want an absolute risk reduction of at least about 30 percent to take a cholesterol-lowering drug every day, whereas the actual absolute risk reduction is only about 1 percent. So, the dirty little secret is that, if patients knew the truth about how little these drugs actually worked, almost no one would agree to take them. Doctors are either not educating their patients or actively misinforming them. Given that the majority of patients expect a much larger benefit from statins than they’d get, “there is a tension between the patient’s right to know about benefiting from a preventive drug and the likely reduction in uptake [willingness to take the drugs] if they are so informed,” and learn the truth. This sounds terribly paternalistic, but hundreds of thousands of lives may be at stake.

If patients were fully informed, people would die. About 20 million Americans are on statins. Even if the drugs saved 1 in 100, that could mean hundreds of thousands of lives lost if everyone stopped taking their statins. “It is ironic that informing patients about statins would increase the very outcomes they were designed to prevent.”

September 23, 2025

Should You Take Statins?

How can you calculate your own personal heart disease risk to help you determine if you should start on a cholesterol-lowering statin drug?

The muscle-related side effects from cholesterol-lowering statins “are often severe enough for patients to stop taking the drug. Of course, these side effects could be coincidental or psychosomatic and have nothing to do with the drug,” given that many clinical trials show such side effects are rare. “It is also possible that previous clinical trials”—funded by the drug companies themselves—“under-recorded the side effects of statins.” The bottom line is that there’s an urgent need to establish the true incidence of statin side effects.

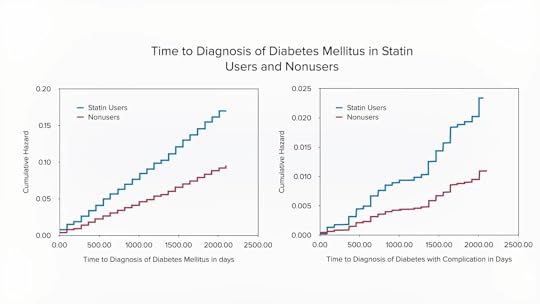

“What proportion of symptomatic side effects in patients taking statins are genuinely caused by the drug?” That’s the title of a journal article that reports that, even in trials funded by Big Pharma, “only a small minority of symptoms reported on statins are genuinely due to the statins,” and those taking statins are significantly more likely to develop type 2 diabetes than those randomized to placebo sugar pills. Why? We’re still not exactly sure, but statins may have the double-whammy effect of impairing insulin secretion from the pancreas while also diminishing insulin’s effectiveness by increasing insulin resistance.

Even short-term use of statins may “approximately double the odds of developing diabetes and diabetic complications.” As shown below and at 1:49 in my video Who Should Take Statins?, fewer people develop diabetes and diabetic complications off statins over a period of about five years than those who do develop diabetes while on statins. “Of more concern, this increased risk persisted for at least 5 years after statin use stopped.”

“In view of the overwhelming benefit of statins in the reduction of cardiovascular events,” the number one killer of men and women, any increase in risk of diabetes, our seventh leading cause of death, would be outweighed by any cardiovascular benefits, right? That’s a false dichotomy. We don’t have to choose between heart disease and diabetes. We can treat the cause of both with the same diet and lifestyle changes. The diet that can not only stop heart disease, but also reverse it, is the same one that can reverse type 2 diabetes. But what if, for whatever reason, you refuse to change your diet and lifestyle? In that case, what are the risks and benefits of starting statins? Don’t expect to get the full scoop from your doctor, as most seemed clueless about statins’ causal link with diabetes, so only a small fraction even bring it up with their patients.

“Overall, in patients for whom statin treatment is recommended by current guidelines, the benefits greatly outweigh the risks.” But that’s for you to decide. Before we quantify exactly what the risks and benefits are, what exactly are the recommendations of current guidelines?

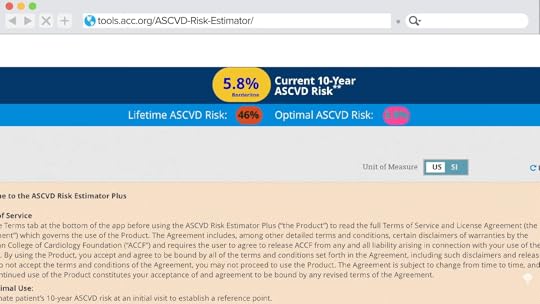

How should you decide if a statin is right for you? “If you have a history of heart disease or stroke, taking a statin medication is recommended, without considering your cholesterol levels.” Period. Full stop. No discussion needed. “If you do not yet have any known cardiovascular disease,” then the decision should be based on calculating your own personal risk. If you know your cholesterol and blood pressure numbers, it’s easy to do that online with the American College of Cardiology risk estimator or the Framingham risk profiler.

My favorite is the American College of Cardiology’s estimator because it gives you your current ten-year risk and also your lifetime risk. So, for a person with a 5.8 percent risk of having a heart attack or stroke within the next decade, if they don’t clean up their act, that lifetime risk jumps to 46 percent, nearly a flip of the coin. If they improved their cholesterol and blood pressure, though, they could reduce that risk by more than tenfold, down to 3.9 percent, as shown below and at 4:11 in my video.

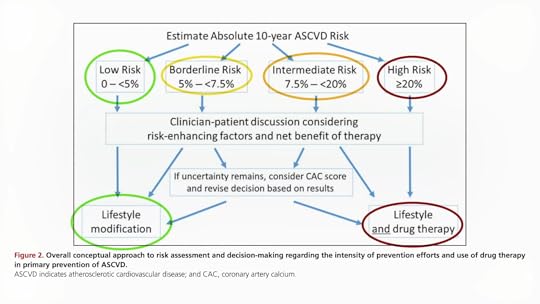

Since the statin decision is based on your ten-year risk, what do you do with that number? As you can see here and at 4:48 in my video, under the current guidelines, if your ten-year risk is under 5 percent, then, unless there are extenuating circumstances, you should just stick to diet, exercise, and smoking cessation to bring down your numbers. In contrast, if your ten-year risk hits 20 percent, then the recommendation is to add a statin drug on top of making lifestyle modifications. Unless there are risk-enhancing factors, the tendency is to stick with lifestyle changes if risk is less than 7.5 percent and to move towards adding drugs if above 7.5 percent.

Risk-enhancing factors that your doctor should take into account when helping you make the decision include a bad family history, really high LDL cholesterol, metabolic syndrome, chronic kidney or inflammatory conditions, or persistently high triglycerides, C-reactive protein, or LP(a). You can see the whole list here and at 4:54 in my video.

If you’re still uncertain, guidelines suggest you consider getting a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score, but even though the radiation exposure from that test is relatively low these days, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has explicitly concluded that the current evidence is insufficient to conclude that the benefits outweigh the harms.

September 18, 2025

Are Doctors Knowledgeable About Nutrition?

Do you know more about basic nutrition than most doctors?

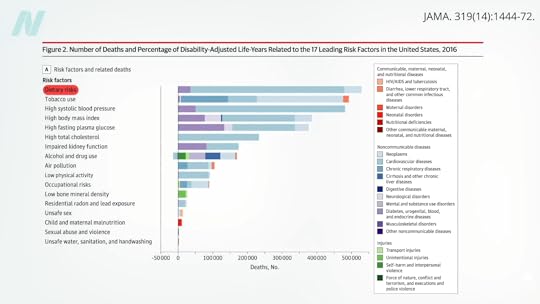

“A poor diet now outranks smoking as the leading cause of death globally and in the United States, according to the latest data.” The top killer of Americans is the American diet, as you can see below and at 0:23 in my video How Much Do Doctors Actually Know About Nutrition?.

If diet is humanity’s number one killer, then, obviously, nutrition is the number one subject taught in medical school, right? Sadly, “medical students around the world [are] poorly trained in nutrition.” It isn’t that medical students aren’t interested in learning about it. In fact, “interest in nutrition was ‘uniformly high’ among medical students,” but medical schools just aren’t teaching it. “Without a solid foundation of clinical nutrition knowledge and skills, physicians worldwide are generally not equipped to even begin to have an informed nutrition conversation with their patients….”

How bad is it? One study, “Assessing the clinical nutrition knowledge of medical doctors,” found the majority of participants got 70 percent of the questions wrong—and they were multiple choice questions, so they should have gotten about a fifth of them right just by chance. “Wrong answers in the…knowledge test were not limited to difficult or demanding questions” either. For example, less than half of the doctors were able to guess how many calories are in fat, carbohydrates, and protein; only one in ten knew the recommended protein intake; and only about one in three knew what a healthy body mass index (BMI) was. We’re talking about really basic nutrition knowledge.

Even worse, not only did the majority of medical doctors get a failing grade, but 30 percent of those who failed had “a high self-perception of their CN [clinical nutrition] expertise.” They weren’t only clueless about nutrition; they were clueless that they were clueless about nutrition, a particularly bad combination given that doctors are “trusted and influential sources” of healthy eating advice. “For those consumers who get information from their personal healthcare professional, 78% indicate making a change in their eating habits as a result of those conversations.” So, if the doctor got everything they know from some article in a magazine while waiting in the grocery store checkout aisle, that’s what the patients will be following.

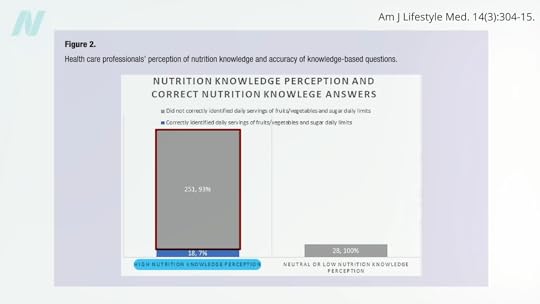

Of doctors surveyed, “only 25% correctly identified the American Heart Association recommended number of fruit and vegetable servings per day, and fewer still (20%) were aware of the recommended daily added sugar limit for adults.” So how are they going to counsel their patients? And get ready for this: Of the doctors who perceived themselves as having high nutrition knowledge, 93 percent couldn’t answer those two basic multiple-choice questions, as seen here and at 2:39 in my video.

“Physicians with no genuine expertise in, say, neurosurgery [brain surgery] are neither likely to broadcast detailed opinions on that topic nor to have their ‘expert’ opinions solicited by the media. Most topical domains in medicine enjoy such respect: we defer expert opinion and commentary to actual experts. Not so nutrition, where the common knowledge that physicians are generally ill-trained in this area is conjoined to routine invitations to physicians for their expert opinions on the matter. All too many are willing to provide theirs, absent any basis for actual expertise…” Or worse, they’re “often made on the basis of native bias and personal preference, at times directly tethered to personal gain—such as diet book sales—and so arises yet another ethical challenge.” That’s one of the reasons all the proceeds I receive from my books are donated directly to charity. I don’t want even the appearance of any conflicts of interest.

“In a culture that routinely fails to distinguish expertise from mere opinion or personal anecdote, we physicians should be doing all we can to establish relevant barriers to entry for expert opinion in this [diet and nutrition], as in all other matters of genuine medical significance.” I mean, we aren’t talking celebrity gossip. Lives are at stake. “Entire industries are devoted to marketing messages that may conspire directly against well-informed medical advice in this area.”

“Medical education must be brought up to date. For physicians to be ill-trained in the very area most impactful on the rate of premature death at the population level is an absurd anachronism….The mission of medicine is to protect, defend, and advance the human condition. That mission cannot be fulfilled if the diet is neglected.”

A possible starting place? “Physicians and health care organizations can collectively begin to emphasize their seriousness about nutrition in health care by practicing what they (theoretically) preach. Is it appropriate to serve pizza and soft drinks at a resident conference while bemoaning the high prevalence of obesity and encouraging patients to eat healthier? A similarly poor example exists in medical conferences, including national meetings, where some morning sessions are accompanied by foods such as donuts and sausage.”

September 16, 2025

Fiber or Low FODMAP for SIBO?

It may not be the number of bacteria growing in our small intestine, but the type of bacteria, which can be corrected with diet.

When researchers tested more than a thousand patients suffering for longer than six months from symptoms typical with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), such as excess gas, bloating, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, but who do not appear to have anything more serious going on, like inflammatory bowel disease, a significant percentage were found to be suffering from lactose intolerance—intolerance to the milk sugar lactose. In infancy, we have an enzyme called lactase in our small intestine that digests milk sugar, but, understandably, most of us lose it after weaning. “Although genetic mutation has led to persistence of lactase in adults, about 75% of the world’s population malabsorbs lactose after age 30” and have lactose intolerance. However, a third of the patients were diagnosed with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

“The evidence for SIBO and IBS is shrouded in controversy, predominantly because of the fact that the [breath] tests used in clinical practice to diagnose SIBO are not valid,” as I’ve explored before. As well, the implications of having more versus fewer bacteria growing in the small intestine are unclear since the number doesn’t seem to correlate with the symptoms. It turns out it isn’t the number of bugs growing in the small intestine, but the type of bugs. So, it’s “small intestinal microbial dysbiosis”—not overgrowth in general, but the wrong kind of growth—that appears to underlie symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders, like IBS.

How can we prevent this from happening? The symptoms appear to be correlated with a significant drop in the number of Prevotella. Remember them? Prevotella are healthy fiber feeders, “suggestive of a higher fiber intake in healthy individuals,” while the bugs found more in symptomatic patients ate sugar, which “may reflect a higher dietary intake of simple sugars.” However, correlation doesn’t mean causation. To prove cause and effect, we have to put it to the test, which is exactly what researchers did.

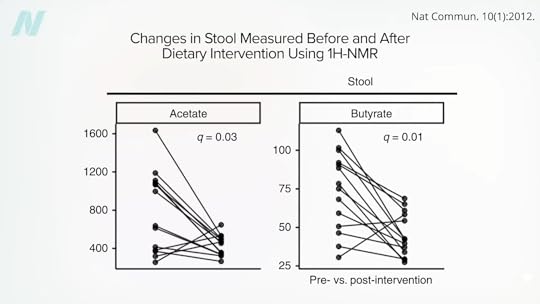

“Switching a group of healthy individuals who habitually ate a high-fibre diet (>11g per 1,000 calories) to a low-fibre diet (<10g per day) containing a high concentration of simple sugars for 7 days produced striking results. First, 80% developed de novo [new] gastrointestinal symptoms such as bloating and abdominal pain that resolved on resumption of their habitual high-fibre diet. Second, diet-related changes in the small intestinal microbiome were predictive of symptoms (such as bloating and abdominal discomfort) and linked to an alteration in duodenal [intestinal] permeability.” In other words, they developed a leaky gut within seven days. And, while some went from SIBO positive to SIBO negative and others from SIBO negative to SIBO positive, it didn’t matter because the number of bacteria growing didn’t correlate with symptoms. It was the type of bacteria growing, as you can see below, and at 3:12 in my video Fiber vs. Low FODMAP for SIBO Symptoms.

No wonder their guts got leaky. Levels of short-chain fatty acids plummeted. Those are the magical by-products our good gut bugs make from fiber, which “play an important role in epithelial [intestinal] barrier integrity,” meaning they keep our gut from getting leaky.

So, while we don’t have sound data to suggest that something like a low FODMAP diet has any benefit for patients with SIBO symptoms, there have been more than a dozen randomized controlled trials that have put fiber to the test. Overall, researchers found there was a significant improvement in symptoms among those randomized to increase their fiber intake. That may help explain why “high-fiber, plant-based diets can prevent many diseases common in industrialized societies.” Such diets have this effect “on the composition and metabolic activity of the colonic microbiota.” Our good gut bugs take plant residues like fiber and produce “health-promoting and cancer-suppressing metabolites” like short-chain fatty acids, which have profound anti-inflammatory properties. “All the evidence points to a physiological need for ~50 g fiber per day, which is the amount contained in the traditional African diet and associated with the prevention of westernized diseases.” That is approximately twice the typical recommendation and three times more than what most people get on a daily basis. Perhaps it should be no surprise that we need so much. Even though we split from chimpanzees millions of years ago, “there is still broad congruency” in the composition of our respective microbiomes to this day. While they’re still eating their 98 to 99 percent plant-based diets to feed their friendly flora with fiber, we’ve largely removed fiber-rich foods from our food supply.