Michael Greger's Blog, page 16

July 2, 2024

Are We Polar Bears in a Jungle?

Rather than being some kind of disorder or a failure of willpower, weight gain is largely a normal response by normal people to an abnormal situation.

It’s been said that “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” The known genetic contribution to obesity may be small, but, in a certain sense, you could argue that it’s all in our genes. The excess consumption of available calories may be hardwired into our DNA. We were born to eat.

Throughout human history and beyond, we existed in survival mode—in unpredictable scarcity. We’ve been programmed with a powerful drive to eat as much as we can while we can and just store the rest for later. Food availability could never be taken for granted, so those who ate more at the moment and were best able to store more fat for the future might better survive subsequent shortages to pass along their genes. So, generation after generation, millennia after millennia, those with lesser appetites may have died out, while those who gorged may have selectively lived long enough to pass along their genetic predisposition to eat and store more calories. That may be how we evolved into such voracious calorie-conserving machines. Now that we’re no longer living in such lean times, though, we’re no longer so lean ourselves.

What I just described is the “thrifty gene” concept proposed in 1962. As I discuss in my video The Thrifty Gene Theory: Survival of the Fattest, it suggests that obesity is the result of a “‘mismatch’ between the environment in which humans evolved and our modern environment”—like being a polar bear in a jungle. All that fur and fat may have given polar bears an edge in the Arctic but would be decidedly disadvantageous in the Congo. Similarly, a propensity to pack on the pounds may have been a plus in prehistoric times but can turn into a liability when our scarcity-sculpted biology is plopped down into the land of plenty. So, it’s not gluttony or sloth. Obesity may simply be “a normal response to an abnormal environment.”

Much of our physiology is finely tuned to stay within a narrow range of upper and lower limits. If we get too hot, we sweat; if we get too cold, we shiver. Our body has mechanisms to keep us in balance. In contrast, our bodies have had little reason to develop an upper limit to the accumulation of body fat. In the beginning, there may have been evolutionary pressures to keep lithe and nimble in the face of predation, but thanks to things like weapons and fire, we haven’t had to outrun as many saber-toothed tigers for about two million years or so. This may have left our genes with the one-sided selection pressures to binge on every morsel in sight and stockpile as many calories as possible in our bodies.

What was once adaptive is now a problem—or at least so says the thrifty gene hypothesis that originated more than half a century ago. It “provides a simple and elegant explanation for the modern obesity epidemic and was quickly embraced by scientists and lay people alike.” Although the researcher, James Neel, later distanced himself from the original proposal, the basic premise, despite remaining mostly theoretical, is still “largely accepted” by the scientific community, and the implications are profound.

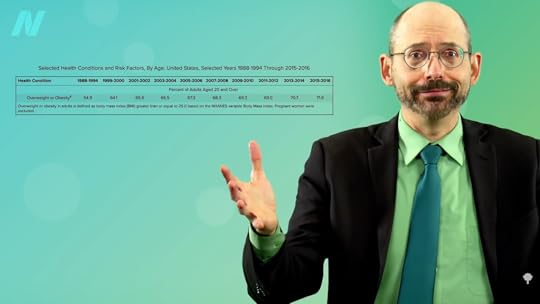

In 2013, the American Medical Association voted to classify obesity as a disease (going against the advice of its own Council on Science and Public Health). Not that it necessarily matters what we call it, but disease implies dysfunction. Bariatric drugs and surgery are not correcting an anomaly in human physiology. Our bodies are just doing what they were designed to do in the face of excess calories. Rather than being some sort of disorder, weight gain is largely “a normal response by normal people to an abnormal environment.” As you can see below and at 4:12 in my video, more than 70 percent of Americans are now overweight. It’s normal.

“A body gaining weight when excess calories are available for consumption is behaving normally. Efforts to curtail such weight gain with drugs [or surgery] are not efforts to correct an anomaly in human physiology, but rather to deconstruct and reconstruct its normal operations at the core.”

If weight gain is largely a normal response by normal people to an abnormal situation, what exactly is that abnormal situation? Calorie-Rich-And-Processed Foods. (I’ll let you work out the acronym.) That’s the topic we’ll turn to next.

This is the third in an 11-video series on the history of the obesity epidemic. If you missed the first two, see The Role of Diet vs. Exercise in the Obesity Epidemic and The Role of Genes in the Obesity Epidemic.

There are eight more coming up. See the related posts below.

June 27, 2024

What Is the Role of Our Genes in the Obesity Epidemic?

The “fat gene” accounts for less than 1 percent of the differences in size between people.

To date, about a hundred genetic markers have been linked to obesity, but when you put them all together, overall, they account for less than 3 percent of the difference in body mass index (BMI) between people. You may have heard about the “fat gene,” called FTO, short for FaT mass and Obesity-associated). It’s the gene most strongly linked to obesity, but it explains less than 1 percent of the difference in BMI between people, a mere 0.34 percent.

As I discuss in my video The Role of Genes in the Obesity Epidemic, FTO codes for a brain protein that appears to affect our appetite. Are you one of the billion people who carry the FTO susceptibility genes? It doesn’t matter because it only appears to result in a difference in intake of a few hundred extra calories a year. The energy imbalance that led to the obesity epidemic is on the order of hundreds of calories a day, and that’s the gene known so far to have the most effect. The chances of accurately predicting obesity risk based on FTO status is “only slightly better than tossing a coin.” In other words, no, those genes don’t make you look fat.

When it comes to obesity, the power of our genes is nothing compared to the power of our fork. Even the small influence the FTO gene does have appears to be weaker among those who are physically active and may be abolished completely in those eating healthier diets. FTO only appears to affect those eating diets higher in saturated fat, which is predominantly found in meat, dairy, and junk food. Those eating more healthfully appear to be at no greater risk of weight gain, even if they inherited the “fat gene” from both of their parents.

Physiologically, FTO gene status does not appear to affect our ability to lose weight. Psychologically, knowing we’re at increased genetic risk for obesity may motivate some people to eat and live more healthfully, but it may cause others to fatalistically throw their hands up in the air and resign themselves to thinking that it just runs in their family, as you can see in the graph below and at 2:11 in my video. Obesity does tend to run in families, but so do lousy diets.

Comparing the weight of biological versus adopted children can help tease out the contributions of lifestyles versus genetics. Children growing up with two overweight biological parents were found to be 27 percent more likely to be overweight themselves, whereas adopted children placed in a home with two overweight parents were 21 percent more likely to be overweight. So, genetics do play a role, but this suggests that it’s more the children’s environment than their DNA.

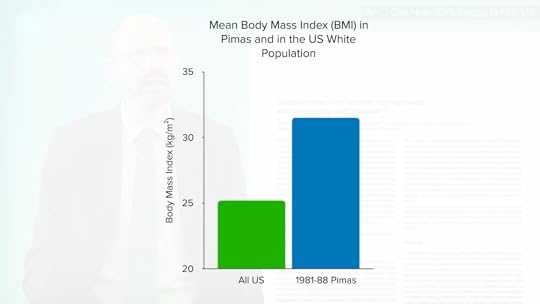

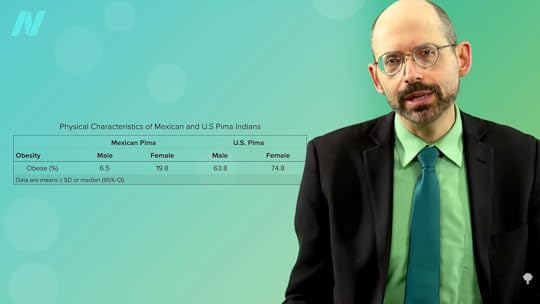

One of the most dramatic examples of the power of diet over DNA comes from the Pima Indians of Arizona. As you can see in the graph below and at 3:05 in my video, they not only have among the highest rates of obesity, but they also have the highest rates of diabetes in the world. This has been ascribed to their relatively fuel-efficient genetic makeup. Their propensity to store calories may have served them well in times of scarcity when they were living off of corn, beans, and squash, but when the area became “settled,” their source of water, the Gila River, was diverted upstream. Those who survived the ensuing famine had to abandon their traditional diet to live off of government food programs and chronic disease rates skyrocketed. Same genes, but different diet, different result.

In fact, a natural experiment was set up. The Pima living over the border in Mexico come from the same genetic pool but were able to maintain more of their traditional lifestyle, sticking with their main staples of beans, wheat flour tortillas, and potatoes. Same genes, but seven times less obesity and about four times less diabetes. You can see those graphs below and at 3:58 and 4:02 in my video. Genes may load the gun, but diet pulls the trigger.

Of course, it’s not our genes! Our genes didn’t suddenly change 40 years ago. At the same time, though, in a certain sense, it could be thought of as all in our genes. That’s the topic of my next video The Thrifty Gene Theory: Survival of the Fattest.

This is the second in an 11-video series on the obesity epidemic. If you missed the first one, check out The Role of Diet vs. Exercise in the Obesity Epidemic.

June 25, 2024

The Roles Diet and Exercise Play in the Obesity Epidemic

The common explanations for the cause of the obesity epidemic put forward by the food industry and policymakers, such as inactivity or a lack of willpower, are not only wrong, but actively harmful fallacies.

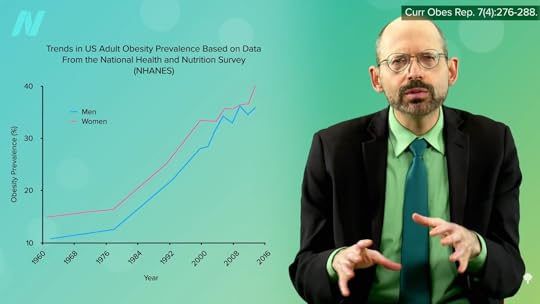

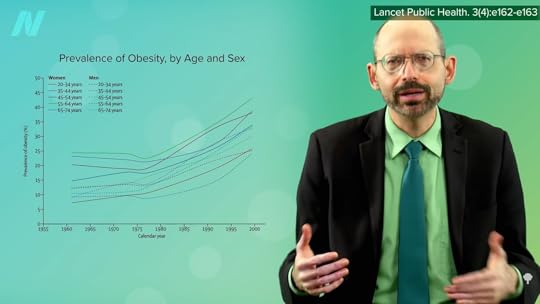

Obesity isn’t new, but the obesity epidemic is. We went from a few corpulent kings and queens, like Henry VIII or Louis VI (known as Louis le Gros, or “Louis the Fat”), to a pandemic of obesity, now considered to be “arguably the gravest and most poorly controlled public health threat of our time.” As you can see below and at 0:34 in my video The Role of Diet vs. Exercise in the Obesity Epidemic, about 37 percent of American men are obese and 41 percent of American women, with no end in sight. Earlier reports had suggested that the rise in obesity was at least slowing down, but even that doesn’t appear to be the case. Similarly, we had thought we were turning the corner on childhood obesity “[a]fter 35 years of unremittingly bad news,” but the bad news continues. Childhood and adolescent obesity rates have continued to rise, now into the fourth decade.

Over the last century, obesity appears to have jumped ten-fold, from about 1 in 30 to now 1 in 3, but it wasn’t a steady rise. As you can see in the graph below and at 1:15 in my video, something seems to have happened around the late 1970s—and not just in the United States, but around the globe. The obesity pandemic took off at about the same time in the 1970s and 1980s in most high-income countries. The fact that the rapid rise “seemed to begin almost concurrently” across the industrialized world suggests a common cause. What might that trigger have been?

Any potential driver would have to be global and “coincide with the upswing of the epidemic.” So, the change would have had to have started about 40 years ago and would have had to have been able to spread rapidly around the globe. Let’s see how all the various theories stack up. For example, as you can see below and at 1:55 in my video, some have blamed changes in our built environment and shifts in city planning that have made our communities less conducive to walking, biking, and grocery shopping. That doesn’t meet our criteria for a credible cause, though, because there was no universal, simultaneous change in our neighborhoods within that time frame.

When researchers surveyed hundreds of policymakers, most blamed the obesity epidemic on a “lack of personal motivation.” Do you see how little sense that makes? In the United States, for example, obesity shot up across the entire population in the late 1970s, as you can see at 2:26 in my video. I concur with the researchers who “believe it is implausible that each age, sex, and ethnic group, with massive differences in life experience and attitudes, had a simultaneous decline in willpower related to healthy nutrition or exercise.” More plausible than a global change like our characters would be some global change like our lives.

The food industry blames inactivity. “If all consumers exercised,” said the CEO of PepsiCo, “obesity wouldn’t exist.” Coca-Cola went a step further, spending $1.5 million to create the Global Energy Balance Network to downplay the role of diet. Leaked emails show the company planned on using the front to “serve as a ‘weapon’ to ‘change the conversation’ about obesity in its ‘war’ with public health.

This tactic is so common among food and beverage companies that it even has a name: “leanwashing.” You’ve heard of greenwashing, where companies deceptively pretend to be environmentally friendly. Leanwashing is the term used to describe companies that try to position themselves as helping to solve the obesity crisis when they’re instead directly contributing to it. For example, the largest food company in the world, Nestlé, has “rebranded itself as the ‘world’s leading nutrition, health and wellness company.” Yes, that Nestlé, makers of Nesquik, Cookie Crisp, and historically more than a hundred different brands of candy, including Butterfinger, Kit Kat, Goobers, Gobstoppers, Runts, and Nerds. Another one of its slogans is “Good Food, Good Life.” Its Raisinets may have some fruit, but Nestlé seems to me more Willy Wonka than wellness.

The constant corporate drumbeat of overemphasis on physical inactivity appears to be working. In response to the Harris poll question, “Which of these do you think are the major reasons why obesity has increased?,” a “huge majority of 83% chose lack of exercise, while only 34% chose excessive calorie consumption.” “Confusion about the effect of exercise on the energy balance” has been identified as one of the most common misconceptions about obesity. The scientific community has “come to a fairly decisive conclusion” that the factors governing calorie intake more powerfully affect overall calorie balance. It’s our fast food more than our slow motion.

“There is considerable debate in the literature today about whether physical activity has any role whatsoever in the epidemic of obesity that has swept the globe since the 1980s.” The increase in caloric intake per person is more than enough to explain the obesity epidemic in the United States and also explain it globally. If anything, the level of physical activity over the last few decades has gone up slightly in both Europe and North America. Ironically, this may be a result of the extra energy it takes to move around our heavier bodies, making it a consequence of the obesity problem rather than the cause.

“Formal exercise plays a very small role in the total daily physical activity energy expenditure.” Think how much more physical work people used to do in the workplace, on the farm, or even in the home. It’s not just the shift in collar color from blue to white. Increasing automation, computerization, mechanization, motorization, and urbanization have all contributed to increasingly more sedentary lifestyles over the last century—and that’s the problem with the theory. The occupational shifts and advent of labor-saving devices “have been gradual and largely predated the dramatic increase in weight gain across the developed world in the past few decades.” Washing machines, vacuum cleaners, and the Model T were all invented before 1910. Indeed, when put to the test using state-of-the-art methods to measure energy in and energy out, it was caloric intake, not physical activity, that predicted weight gain over time.

The common misconception that obesity is mostly due to lack of exercise may not just be a benign fallacy. Personal theories of causation appear to impact people’s weight. Those who blame insufficient exercise are significantly more likely to be overweight than those who implicate a poor diet. Put those who believe lack of exercise causes obesity in a room with chocolate, and they can covertly be observed consuming more candy. Those holding that view may be different in other ways, though. You can’t prove cause and effect until you put it to the test. And, indeed, as you can see in the graph below, and at 7:22 in my video, people randomized to read an article implicating inactivity went on to eat significantly more sweets than those reading about research that indicated diet. A similar study found that those presented with research blaming genetics subsequently ate significantly more cookies. The title of that paper? “An Unintended Way in Which the Fat Gene Might Make You Fat.”

When I sat down to write How Not to Diet, I knew this “what triggered the obesity epidemic” was going to be a big question I had to face. Was it inactivity (just kids sitting around playing video games or scrolling on their phones)? Was it genetic? Was it epigenetic (something turning on our fat genes)? Or was it just the food? Were we eating more fat all of a sudden? More carbs? More processed foods? Or were we just eating more period, because of bigger serving sizes or more snacking? Inquiring minds wanted to know.

This is the first in an 11-video series to answer this question, which I originally released in a two-hour webinar in 2020. Check out the webinar digital download here. Or, check them out in the related posts below.

June 20, 2024

What Should We Eat?

Here is a review of reviews on the health effects of animal foods versus plant foods.

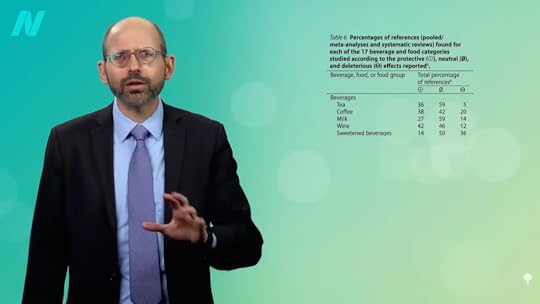

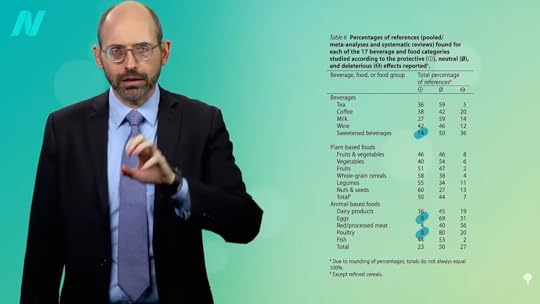

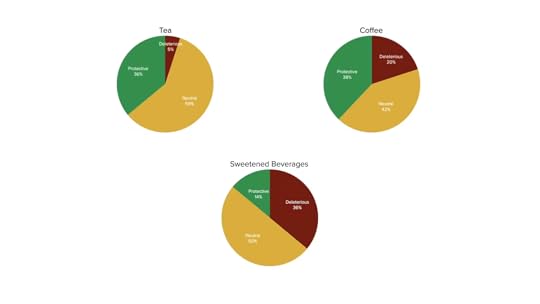

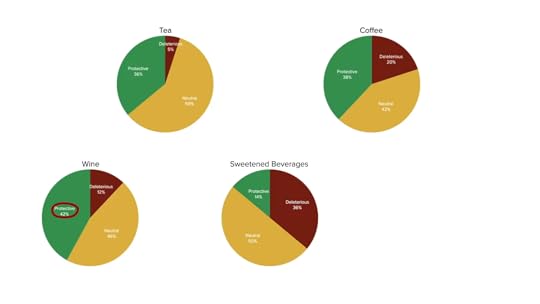

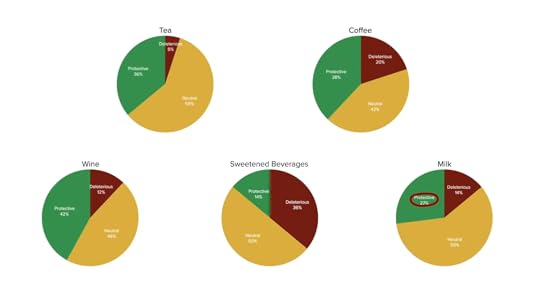

Instead of looking only at individual studies or individual reviews of studies, what if you looked at a review of reviews? In my last video, I covered beverages. As you can see below and at 0:20 in my video Friday Favorites: What Are the Best Foods?, the majority of reviews found some effects either way, finding at least some benefits to tea, coffee, wine, and milk, but not for sweetened beverages, such as soda. As I explored in depth, this approach isn’t perfect. It doesn’t take into account such issues as conflicts of interest and industry funding of studies, but it can offer an interesting bird’s-eye view of what’s out in the medical literature. So, what did the data show for food groups?

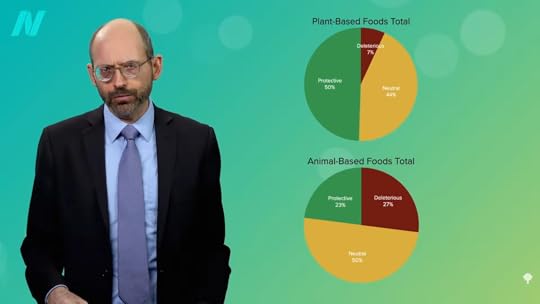

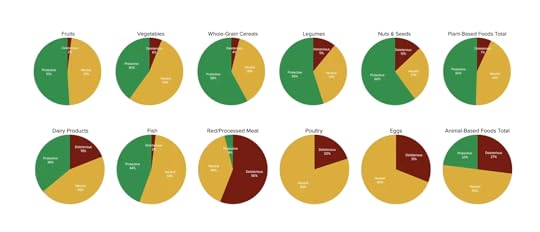

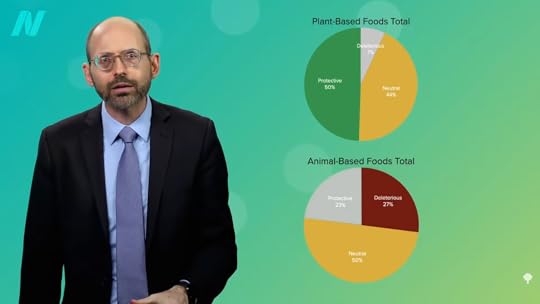

You’ll note the first thing the authors did was divide everything into plant-based foods or animal-based foods. For the broadest takeaway, we can look at the totals. The vast majority of reviews on whole plant foods show protective or, at the very least, neutral effects, whereas most reviews of animal-based foods identified deleterious health effects or, at best, neutral effects, as you can see at 1:14 in my video.

Let’s break these down. As you can see in the graph below and at 1:23, the plant foods consistently rate uniformly well, reflecting the total, but the animal foods vary considerably. If it weren’t for dairy and fish, the total for animal foods would swing almost entirely neutral or negative.

I talked about the effects of funding by the dairy industry in my last blog, as well as substitution effects. For instance, those who drink milk may be less likely to drink soda, a beverage even more universally condemned than dairy, so the protective effects may be relative. They may arise not necessarily from what is being consumed, but rather from what is being avoided. This may best explain the fish findings. After all, the prototypical choice is between chicken and fish, not chicken and chickpeas.

I talked about the effects of funding by the dairy industry in my last blog, as well as substitution effects. For instance, those who drink milk may be less likely to drink soda, a beverage even more universally condemned than dairy, so the protective effects may be relative. They may arise not necessarily from what is being consumed, but rather from what is being avoided. This may best explain the fish findings. After all, the prototypical choice is between chicken and fish, not chicken and chickpeas.

Not a single review found a single protective effect of poultry consumption. Even the soda industry could come up with 14 percent protective effects! But, despite all of the funding from the National Chicken Council and the American Egg Board, chicken, and eggs got big fat goose eggs, as you can see below and at 2:20 in my video.

Also, like the calcium in dairy, there are healthful components of fish, such as the long-chain omega-3 fatty acids. Not for heart health, though. In “the most extensive systematic assessment of effects of omega-3 fats on cardiovascular health to date,” increasing intake of fish oil fats had little or no effect on cardiovascular health. If anything, it was the plant-based omega-3s found in flaxseeds and walnuts that were protective. The long-chain omega-3s are important for brain health. Thankfully, just like there are best-of-both-worlds non-dairy sources of calcium, there are pollutant-free sources of the long-chain omega-3s, EPA, and DHA, as well.

The bottom line, as you can see below and at 3:04 in my video, is that when it comes to diet-related diseases, such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, mental health, bone health, cardiovascular disease, and cancers, even if you lump together all the animal foods, ignore any industry-funding effects, and just take the existing body of evidence at face value, nine out of ten study compilations show that whole plant foods are, in the very least, not bad.

However, about eight out of ten of the reviews on animal products show them to be not good, as shown in the graph below and at 3:24 in my video.

This reminds me of my Flashback Friday: What Are the Healthiest Foods? video, which you may find to be helpful for some broad takeaways.

If you missed my previous video, check out Friday Favorites: What Are the Best Beverages?.

The omega-3s video I mentioned is Should Vegans Take DHA to Preserve Brain Function?.

For more on eggs, see here.

On fish, go here.

And, for poultry, see related posts below.

June 18, 2024

What Should We Drink?

Here is a review of reviews on the health effects of tea, coffee, milk, wine, and soda.

If you’ve watched my videos or read my books, you’ve heard me say, time and again, the best available balance of evidence. What does that mean? When making decisions as life-or-death important as what to feed ourselves and our families, it matters less what a single study says, but rather what the totality of peer-reviewed science has to say.

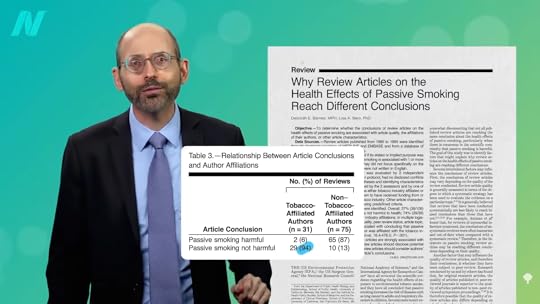

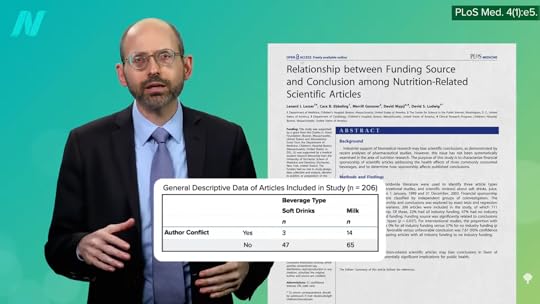

Individual studies can lead to headlines like “Study Finds No Link Between Secondhand Smoke and Cancer,” but to know if there is a link between secondhand smoke and lung cancer, it would be better to look at a review or meta-analysis that compiles multiple studies. The problem is that some reviews say one thing—for instance, “breathing other people’s tobacco smoke is a cause of lung cancer”—and other reviews say another—such as, the effects of secondhand smoke are insignificant and further such talk may “foster irrational fears.” And, while we’re at it, you can indulge in “active smoking of some 4-5 cigarettes per day” without really worrying about it, so light up!

Why do review articles on the health effects of secondhand smoke reach such different conclusions? As you can imagine, about 90 percent of reviews written by researchers affiliated with the tobacco industry said it was not harmful, whereas you get the opposite number with independent reviews, as you can see below and at 1:18 in my video Friday Favorites: What Are the Best Beverages?. Reviews written by the tobacco industry–affiliated researchers had 88 times the odds of concluding that secondhand smoke was harmless. It was all part of “a deliberate strategy to use scientific consultants to discredit the science…” In other words, “the strategic and long run antidote to the passive smoking issue…is developing and widely publicizing clear-cut, credible, medical evidence that passive smoking [secondhand smoke] is not harmful to the non-smoker’s health.”

Can’t we just stick to the independent reviews? The problem is that industry-funded researchers have all sorts of sneaky ways to get out of declaring conflicts of interest, so it can be hard to follow the money. For instance, it was found that “77% failed to disclose the sources of funding” for their research. But, even without knowing who funded what, the majority of reviews still concluded that secondhand smoke was harmful. So, just as a single study may not be as helpful as looking at a compilation of studies on a topic, a single review may not be as useful as a compilation of reviews. In that case, looking at a review of reviews can give us a better sense of where the best available balance of evidence may lie. When it comes to secondhand smoke, it’s probably best not to inhale, as you can see in the graph below and at 2:30 in my video.

Wouldn’t it be cool if there were reviews of reviews for different foods and drinks? Voila! Enter “Associations Between Food and Beverage Groups and Major Diet-Related Chronic Diseases: An Exhaustive Review of Pooled/Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews.” Let’s start with the drinks. As you can see below and at 2:51 in my video, the findings were classified into three categories: protective, neutral, or deleterious.

First up: tea versus coffee. As you can see in the graph below and at 2:58, most reviews found both beverages to be protective for whichever condition they were studying, but you can see how this supports my recommendation for tea over coffee. Every cup of coffee is a lost opportunity to drink a cup of green tea, which is even healthier.

It’s no surprise that soda sinks to the bottom, as you can see below and at 3:20 in my video, but 14 percent of reviews mentioned the protective effects of drinking soda. What?! Well, most were references to papers like “High Intake of Added Sugar Among Norwegian Children and Adolescents,” a cross-sectional study that found that eighth-grade girls who drank more soda were thinner than girls who drank less. Okay, but that was just a snapshot in time. What do you think is more likely? That the heavier girls were heavier because they drank less soda, or that they drank less sugary soda because they were heavier? Soda abstention may therefore be a consequence of obesity, rather than a cause, yet it gets marked down as having a protective association.

Study design flaws may also account for wine numbers, as seen below and at 4:07 in my video. This review of reviews was published in 2014, before the revolution in our understanding of “alcohol’s evaporating health benefits,” suggesting that the “presumed health benefits from ‘moderate’ alcohol use [may have] finally collapsed”—thanks in part to a systematic error of misclassifying former drinkers as if they were lifelong abstainers, as I revealed in a deep dive in a video series on the subject.

Sometimes there are unexplainable associations. For example, one of the soft drink studies found that increased soda consumption was associated with a lower risk of certain types of esophageal cancers. Don’t tell me. Was the study funded by Coca-Cola? Indeed. Does that help explain the positive milk studies, as you can see in the graph below and at 5:02 in my video? Were they all just funded by the National Dairy Council?

As shown below and at 5:06, even more conflicts of interest have been found among milk studies than soda studies, with industry-funded studies of all such beverages “approximately four to eight times more likely to be favorable to the financial interests of the [study] sponsors than articles without industry-related funding.”

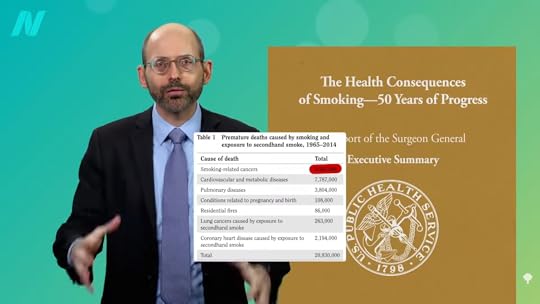

Funding bias aside, though, there could be legitimate reasons for the protective effects associated with milk consumption. After all, those who drink more milk may drink less soda, which is even worse, so they may come out ahead. It may be more than just relative benefits, though. The soda-cancer link seems a little tenuous and not just because of the study’s financial connection to The Coca-Cola Company. It’s hard to imagine a biologically plausible mechanism, whereas even something as universally condemned as tobacco isn’t universally bad. As I’ve explored before, more than 50 studies have consistently found a protective association between nicotine and Parkinson’s disease. Even secondhand smoke may be protective. Of course, you’d still want to avoid it. Passive secondhand smoke may decrease the risk of Parkinson’s, but it increases the risk of stroke, an even deadlier brain disease, not to mention lung cancer and heart disease, which has killed off millions of Americans since the first Surgeon General’s report was released, as you can see below and at 6:20 in my video.

Thankfully, by eating certain vegetables, we may be able to get some of the benefits without the risks, and the same may be true of dairy. As I’ve described before, the consumption of milk is associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer, leading to recommendations suggesting that men may want to cut down or minimize their intake, but milk consumption is also associated with decreased colorectal cancer risk. This appears to be a calcium effect. Thankfully, we may be able to get the best of both worlds by eating high-calcium plant foods, such as greens and beans.

What does our review-of-reviews study conclude about such plant-based foods, in comparison to animal-based foods? We’ll find out next.

Stay tuned for the exhaustive review of meta-analyses and systematic reviews on major diet-related chronic diseases found for food groups in What Are the Best Foods?.

The alcohol video I mentioned is Is It Better to Drink a Little Alcohol Than None at All?, and the Parkinson’s video is Pepper’s and Parkinson’s: The Benefits of Smoking Without the Risks. I also mentioned my Dairy and Cancer video.

What about diet soda? See related posts below.

What’s so bad about alcohol? Check out Can Alcohol Cause Cancer? and Do Any Benefits of Alcohol Outweigh the Risks? for more.

I’ve also got tons of milk. Check here.

My recommendations for the best beverages are water, green tea, and hibiscus herbal tea. Learn more in the related posts below.

June 13, 2024

Headache and Migraine Relief from Foods

Plant-based diets are put to the test for treating migraine headaches.

Headaches are one of the top five reasons people end up in emergency rooms and one of the leading reasons people see their doctors in general. One way to try to prevent them is to identify their triggers and avoid them. Common triggers for migraines include stress, smoking, hunger, sleep issues, certain foods (like chocolate, cheese, and alcohol), your menstrual cycle, or certain weather patterns (like high humidity).

In terms of dietary treatments, the so-called Father of Modern Medicine, William Osler suggested trying a “strict vegetable diet.” After all, the nerve inflammation associated with migraines “may be reduced by a vegan diet as many plant foods are high in anti-inflammatory compounds and antioxidants, and likewise, meat products have been reported to have inflammatory properties.” It wasn’t put to the test, though, for another 117 years.

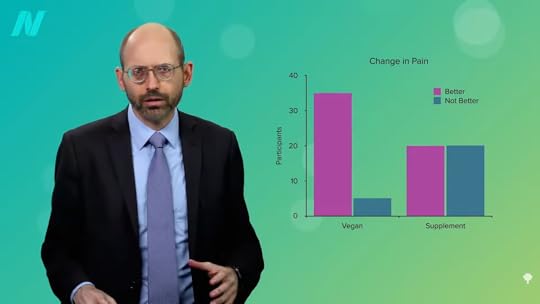

As I discuss in my video Friday Favorites: Foods That Help Headache and Migraine Relief, among study participants given a placebo supplement, half said they got better, while the other half said they didn’t. But, when put on a strictly plant-based diet, they did much better, experiencing a significant drop in the severity of their pain, as you can see in the graph below and at 1:08 in my video.

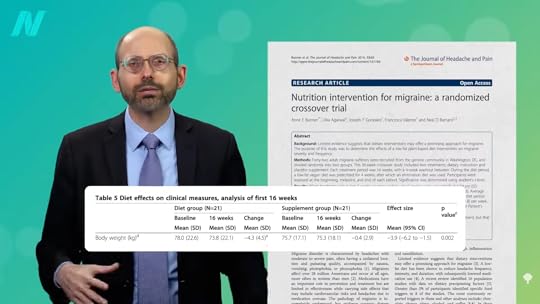

Now, “it is possible that the pain-reducing effects of the vegan diet may be, at least in part, due to weight reduction.” The study participants lost about nine more pounds when they were on the plant-based diet for a month, as shown below, and at 1:22.

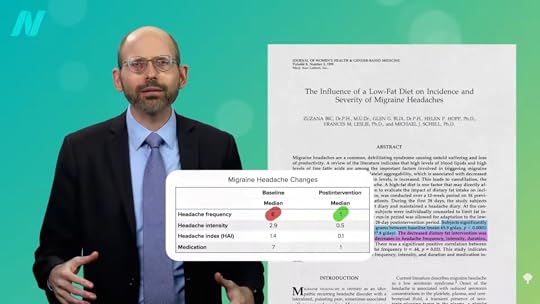

Even just lowering the fat content of the diet may help. Those placed on a month of consuming less than 30 daily grams of fat (for instance, less than two tablespoons of oil all day), experienced “statistically significant decreases in headache frequency, intensity, duration, and medication intake”—a six-fold decrease in the frequency and intensity, as you can see below and at 1:44 in my video. They went from three migraine attacks every two weeks down to just one a month. And, by “low fat,” the researchers didn’t mean SnackWell’s; they meant more fruits, vegetables, and beans. Before the food industry co-opted and corrupted the term, eating “low fat” meant eating an apple, for example, not Kellogg’s Apple Jacks.

Now, they were on a low-fat diet—about 10 percent fat for someone eating 2,500 calories a day. What about just less than 20 percent fat compared to a more normal diet that’s still relatively lower fat than average? As you can see below and at 2:22 in my video, the researchers saw the same significant drops in headache frequency and severity, including a five-fold drop in attacks of severe pain. Since the intervention involved at least a halving of intake of saturated fat, which is mostly found in meat, dairy, and junk, the researchers concluded that reduced consumption of saturated fat may help control migraine attacks—but it isn’t necessarily something they’re getting less of. There are compounds “present in Live green real veggies” that might bind to a migraine-triggering peptide known as calcitonin gene-related peptide, CGRP.

Drug companies have been trying to come up with something that binds to CGRP, but the drugs have failed to be effective. They’re also toxic, which is a problem we don’t have with cabbage, as you can see below and at 3:01 in my video.

Green vegetables also have magnesium. Found throughout the food supply but most concentrated in green leafy vegetables, beans, nuts, seeds, and whole grains, magnesium is the central atom to chlorophyll, as shown below and at 3:15. So, you can see how much magnesium foods have in the produce aisle by the intensity of their green color. Although magnesium supplements do not appear to decrease migraine severity, they may reduce the number of attacks you get in the first place. You can ask your doctor about starting 600 mg of magnesium dicitrate every day, but note that magnesium supplements can cause adverse effects, such as diarrhea, so I recommend getting it the way nature intended—in the form of real food, not supplements.

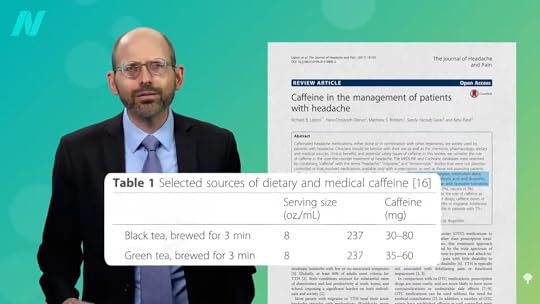

Any foods that may be particularly helpful? You may recall that I’ve talked about ground ginger. What about caffeine? Indeed, combining caffeine with over-the-counter painkillers, like Tylenol, aspirin, or ibuprofen, may boost their efficacy, at doses of about 130 mg for tension-type headaches and 100 mg for migraines. That’s about what you might expect to get in three cups of tea, as you can see below, and at 4:00 in my video. (I believe it is just a coincidence that the principal investigator of this study was named Lipton.)

Please note that you can overdo it. If you take kids and teens with headaches who were drinking 1.5 liters of cola a day and cut the soda, you can cure 90 percent of them. However, this may be a cola effect rather than a caffeine effect.

And, finally, one plant food that may not be the best idea is the Carolina Reaper, the hottest chili pepper in the world. It’s so mind-numbingly hot it can clamp off the arteries in your brain, as seen below and at 4:41 in my video, and you can end up with a “thunderclap headache,” like the 34-year-old man who ate the world’s hottest pepper and ended up in the emergency room. Why am I not surprised it was a man?

I’ve previously covered ginger and topical lavender for migraines. Saffron may help relieve PMS symptoms, including headaches. A more exotic way a plant-based diet can prevent headaches is by helping to keep tapeworms out of your brain.

Though hot peppers can indeed trigger headaches, they may also be used to treat them. Check out my video on relieving cluster headaches with hot sauce.

June 11, 2024

Children’s Cereals: Candy for Breakfast?

Plastering front-of-package nutrient claims on cereal boxes is an attempt to distract us from the incongruity of feeding our children multicolored marshmallows for breakfast.

The American Medical Association started warning people about excess sugar consumption more than 75 years ago, based in part on our understanding that “sugar supplies nothing in nutrition but calories, and the vitamins provided by other foods are sapped by sugar to liberate these calories.” So, added sugars aren’t just empty calories, but negative nutrition. “Thus, the more added sugars one consumes, the more nutritionally depleted one may become.”

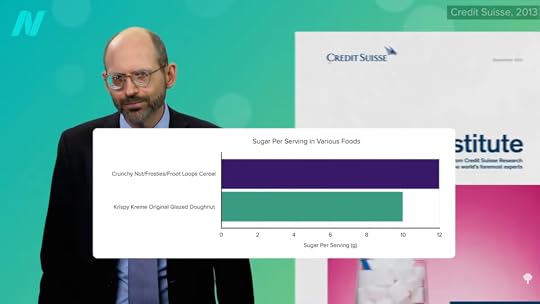

Given the “totality of publicly available scientific evidence,” the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) decided to make processed food manufacturers declare “added sugars” on their nutrition labels. The National Yogurt Association was livid and said it “continues to oppose the ‘added sugars’ declaration,” since it needed “‘added sugars’ to increase palatability” of its products. The junk food association questioned the science, whereas the ice cream folks seemed to imply that consumers are too stupid to “understand or know how to use the added sugar declaration,” so it’s better just to leave it off. The world’s biggest cereal company, Kellogg’s, took a similar tact, opposing it so as not “to confuse consumers.” Should the FDA proceed with such labeling against Kellogg’s objections, the cereal giant pressed that “an added sugars declaration…should be communicated as a footnote.” It claimed that its “goal is to provide consumers with useful information so they can make informed choices.” This is from a company that describes its Froot Loops as “packed with delicious fruity taste, fruity aroma, and bright colors.” Keep in mind that Froot Loops has more sugar than a Krispy Kreme doughnut, as you can see in the graph below and at 1:46 in my video Friday Favorites: Kids’ Breakfast Cereals as Nutritional Façade.

Froot Loops is more than 40 percent sugar by weight! You can see the cereal box’s Nutrition Facts label below and at 1:50 in my video.

The tobacco industry used similar terms, such as “light,” “low,” and “mild” to make its products appear healthier—before it was barred from doing so. “Now sugar interests are fighting similar battles over whether their terminology, including ‘healthy,’ ‘natural,’ ‘naturally sweetened,’ and even ‘lightly sweetened,’ is deceptive to consumers.”

But if you look at the side of a cereal box, as shown below and at 2:13 in my video, you can see all those vitamins and minerals that have been added. That was one of the ways the cereal companies responded to calls for banning sugary cereals. General Mills defended the likes of Franken Berry, Trix, and Lucky Charms for being fortified with essential vitamins.

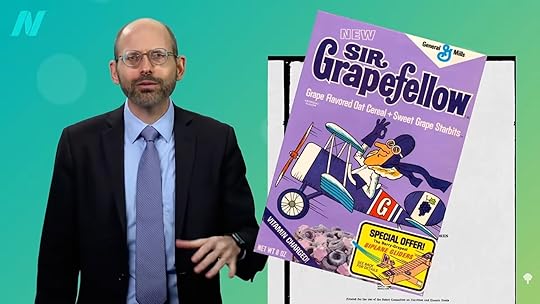

Sir Grapefellow, I learned, was a “grape-flavored oat cereal” complete with “sweet grape star bits”—that is, marshmallows. Don’t worry. It was “vitamin charged!” You can see that cereal box below and at 2:31 in my video.

Sugary breakfast cereals, said Dr. Jean Mayer from Harvard, “are not a complete food even if fortified with eight or 10 vitamins.” Senator McGovern replied, “I think your point is well taken that these products may be mislabeled or more correctly called candy vitamins than cereals.”

Plastering nutrient claims on cereal boxes can create “a ‘nutritional façade’ around a product, acting to distract attention away” from unsavory qualities, such as excess sugar content. Researchers found that the “majority of parents misinterpreted the meaning of claims commonly used on children’s cereals,” raising significant public health concerns. Ironically, cereal boxes bearing low-calorie claims were found to have more calories on average than those without such a claim. The cereal doth protest too much.

Even candy bar companies are getting in on the action, bragging about protein content because of some peanuts. Like the Baby Ruth, a candy bar that has 50 grams of sugar. Froot Loops could be considered breakfast candy, as the same serving would have 40 sugar grams, as you can see below and at 3:45 in my video.

Given that “research suggests that consumers believe front-of-package claims, perceive them to be government-endorsed, and use them to ignore the Nutrition Facts Panel,” there’s been a call from nutrition professionals to consider “an outright ban on all front-of-package claims.” The industry’s short-lived “Smart Choices” label, as you can see below and at 4:13 in my video, was met with disbelief when it was found adorning qualifying cereals like Froot Loops and Cookie Crisp. The processed food industry spent more than a billion dollars lobbying against the adoption of more informative labeling (a traffic-light approach), “opposing most aggressively the use of a red light suggesting that any food was too high in anything.”

I was invited to testify as an expert witness in a case against sugary cereal companies. (I donated my fee, of course.) Check out the related posts below for a video series and blogs that are a result of some of the research I did.

You may also be interested in videos and blogs on the food industry; see related posts below.

June 6, 2024

Is All Vegan Food Healthy?

How do healthier plant-based diets compare to unhealthy plant foods and animal foods when it comes to diabetes risk?

In my video on flexitarians, I discuss how the benefits of eating a plant-based diet are not all-or-nothing. “Simple advice to increase the consumption of plant-derived foods with compensatory [parallel] reductions in the consumption of foods from animal sources confers a survival advantage”— a live-longer advantage. The researchers call it a “pro-vegetarian” eating pattern, one that’s moving in the direction of vegetarianism, “a more gradual and gentle approach.”

If you’re dealing with a serious disease, though, like diabetes, completely “avoiding some problem foods is easier than attempting to moderate their intake. Clinicians would never tell an alcoholic to try to simply cut down on alcohol. Avoiding alcohol entirely is more effective and, in fact, easier for a problem drinker…Paradoxically, asking patients to make a large change may be more effective than making a slow transition. Diet studies show that recommending more significant changes increases the chances that patients can accomplish [them]. It may help to replace the common advice, ‘all things in moderation’ with ‘big changes beget big results.’ Success breeds success. After a few days or weeks of major dietary changes, patients are likely to see improvements in weight and blood glucose [sugar] levels—improvements that reinforce the dietary changes that elicited them. Furthermore, they may enjoy other health benefits of a plant-based diet” that may give them further motivation.

As you can see below and at 1:43 in my video Friday Favorites: Is Vegan Food Always Healthy?, those who choose to eat plant-based for their health say it’s mostly for “general wellness or general disease prevention” or to improve their energy levels or immune function, for example.

They felt it gives them a sense of control over their health, helps them feel better emotionally, improves their overall health, makes them feel better, and more, as shown below and at 1:48. Most felt it was very important for maintaining their health and well-being.

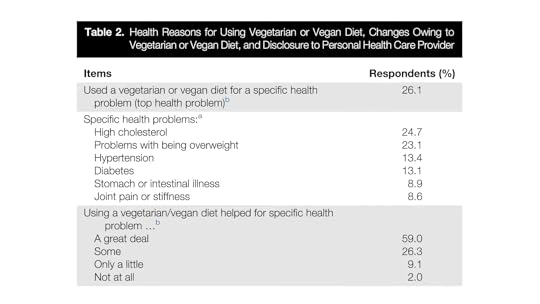

For the minority who used it for a specific health problem, mostly high cholesterol or weight loss, followed by high blood pressure and diabetes, most reported they felt it helped a great deal, as you can see below and at 2:14.

Some choose plant-based diets for other reasons, such as animal welfare or global warming, and it looks like “ethical vegans” are more likely to eat sugary and fatty foods, like vegan donuts, compared to those eating plant-based because of religious or health concerns, as you can see below and at 2:26 in my video.

The veganest vegan could make an egg- and dairy-free cake, covered with frosting, marshmallow fluff, and chocolate syrup, topped with Oreos, and served with a side of Doritos. Or, they may want fruit for dessert, but in the form of Pop-Tarts and Krispy Kreme pies. Vegan, yes. Healthy, no.

“Plant-based diets have been recommended to reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D). However, not all plant foods are necessarily beneficial.” In the pro-vegetarian scoring system I mentioned above, you get points for eating potato chips and French fries because they are technically plant-based, as you can see below and at 3:07 in my video, but Harvard researchers wanted to examine the association of not only an overall plant-based diet, but healthy and unhealthy versions. So, they created the same kind of pro-vegetarian scoring system, but it was weighted towards any sort of plant-based foods and against animal foods; then, they created a healthful plant-based diet index, where at least some whole plant foods took precedence and Coca-Cola and other sweetened beverages were no longer considered plants. Lastly, they created an unhealthful plant-based diet index by assigning positive scores to processed plant-based junk and negative scores for healthier plant foods and animal foods.

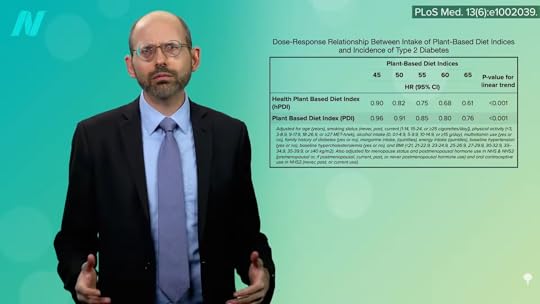

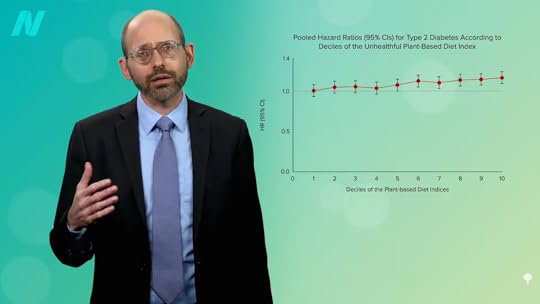

Their findings? As you can see below and at 3:51 in my video, a more plant-based diet, in general, was good for reducing diabetes risk, but eating especially healthy plant-based foods did better, nearly cutting risk in half, while those eating more unhealthy plant foods did worse, as shown in the graph below and at 4:03.

Now, is that because they were also eating more animal foods? People often eat burgers with their fries, so the researchers separated the effects of healthy plant foods, less healthy plant foods, and animal foods on diabetes risk. And, they found that healthy plant foods were protectively associated, animal foods were detrimentally associated, and less healthy plant foods were more neutral when it came to diabetes risk. Below and at 4:32 in my video, you can see the graph that shows higher diabetes risk with more and more animal foods, no protection whatsoever with junky plant foods, and lower and lower diabetes risk associated with more and more healthy whole plant foods in the diet. So, they concluded that, yes, “plant-based diets…are associated with substantially lower risk of developing T2D.” However, it may not be enough to just lower the intake of animal foods; consumption of less healthy plant foods may need to decrease, too.

As a physician, labels like vegetarian and vegan just tell me what you don’t eat, but there are a lot of unhealthy vegetarian fare like French fries, potato chips, and soda pop. That’s why I prefer the term whole food and plant-based nutrition. That tells me what you do eat—a diet centered around the healthiest foods out there.

As a physician, labels like vegetarian and vegan just tell me what you don’t eat, but there are a lot of unhealthy vegetarian fare like French fries, potato chips, and soda pop. That’s why I prefer the term whole food and plant-based nutrition. That tells me what you do eat—a diet centered around the healthiest foods out there.

The video I mentioned is Do Flexitarians Live Longer?.

You may also be interested in some of my past popular videos and blogs on plant-based diets. Check related posts below.

June 4, 2024

How Much Added Sugar Is Okay?

Public health authorities continue to lower the upper tolerable limit of daily added sugar intake.

Dating back to the original “Dietary Goals for the United States” in 1977, also known as the so-called McGovern Report, leading nutrition scientists didn’t only call for a reduction in meat and other sources of saturated fat and cholesterol, such as dairy and eggs, but also sugar. The goal was to reduce America’s sugar intake to no more than 10 percent of our daily diet.

“The conclusions would hang sugar,” reported the president of the Sugar Association. “The McGovern Report has to be neutralized.” The National Cattlemen’s Association was on its side and, just like Big Sugar, appealed to the Senate Select Committee to withdraw the report.

“The Sugar Industry Empire Strikes Back”—and it appeared to work. When the official U.S. Dietary Guidelines were released in 1980 and again in 1985, it was without a specific limit, like 10 percent. It “said, simply, and in just four words, ‘Avoid too much sugar.’” (Whatever that means.) “In 1990, it went to five words, ‘Use sugars only in moderation,’ and in 1995 to six: ‘Choose a diet moderate in sugars.’” In 2000, it at least went back to limiting intake—specifically, “‘Choose beverages and foods to limit your intake of sugars’ (ten words), but even that was too strong. Under pressure from sugar lobbyists, the government agencies substituted the word ‘moderate’ for ‘limit’ so it read ‘Choose beverages and foods to moderate your intake of sugars.’” Then, the 2005 guidelines committee dropped the s-word completely, encouraging Americans to “Choose carbohydrates wisely…” Again, what does that mean? If only there were a dietary guidelines committee that could guide us….

The Sugar Association expressed optimism about that 2005 Committee. In its Sugar E-News, it wrote that Sugar Association Incorporated (SAI) “is committed to the protection and promotion of sucrose [table sugar] consumption. Any disparagement of sugar will be met with forceful, strategic public comments”—and it wasn’t kidding. “In 2003, [the World Health Organization] WHO released a joint report with the Food and Agriculture Organization entitled Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases which, for the first time [since the McGovern Report], called for a reduction in sugar intake to under 10% of total dietary energy [caloric] consumption.” The Sugar Association responded by threatening to get the United States to withdraw all funding from the WHO. You can see it yourself in black and white at 2:22 in my video Friday Favorites: The Recommended Daily Added Sugar Intake. The Sugar Association threatened to pressure Congress to withdraw funding from the World Health Organization—polio vaccinations and AIDS medications be damned! Don’t mess with the candy man. The threat was described as “tantamount to blackmail and worse than any pressure exerted by the tobacco lobby.”

Fifteen years later and 40 years after the first proposed McGovern Report, the 2015 to 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans lays out the 10 percent limit as a key recommendation: “Consume less than 10 percent of calories per day from added sugars.” This is currently exceeded by every age bracket in the United States starting at age one, as you can see in the graph below and at 2:58 in my video, with adolescents averaging 87 grams of sugar a day. That means the average teen is effectively eating 29 sugar packets a day.

The Sugar Association describes the 10 percent limit as “extremely low.” Well, I mean, it is only up to about a dozen spoonsful a day. Of course, there is no dietary requirement for added sugar at all, and every single calorie we get from added sugar is a wasted opportunity to get calories from sources that provide nutrition. To the American Heart Association’s credit, it went further by trying to push added sugar intake down to about 6 percent of calories, for which a single can of soda could send you over the limit. That’s an added sugar limit exceeded by 90 percent of Americans.

In 2017, the American Heart Association (AHA) released its guidelines for children, recommending they get no more than about six teaspoons per day. In that case, a single serving of nearly a hundred cereals on the U.S. market would exceed the entire recommended daily limit. The AHA recommends no added sugars at all for children under the age of two, a recommendation that’s violated in up to 80 percent of toddlers, as you can see below and at 4:20 in my video.

In the United States, “at least 65 countries have implemented dietary guidelines or public health policies to curb sugar consumption to encourage maintenance of healthy body weight.” In the United Kingdom, the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition made new recommendations to reduce added sugars down to 5 percent, which is also the direction the World Health Organization is headed. The WHO always seems to be ahead of the curve. Why? Because its policy-making process is at least partially protected “against industry influence.” Unlike governments, which may have competing interests in commerce and trade, “WHO is exclusively concerned with health.”

I spoke at a hearing of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Committee. Watch the highlights and my speech here: Highlights from the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Hearing.

The sugar industry keeps pretty busy, as you’ll see from my recent videos, Friday Favorites: Are Fortified Kids’ Breakfast Cereals Healthy or Just Candy? and Flashback Friday: Sugar Industry Attempts to Manipulate the Science.

Check the related posts below for my other popular videos and blogs on sugar.

May 30, 2024

Exploring Indian Cuisine with Sheil Shukla

Please tell us a little bit about your work and career.

My name is Sheil Shukla, DO, and I am a board-certified internal medicine physician with Northwestern Medicine in Illinois. I am the creator behind @plantbasedartist on Instagram and the author of the vegan cookbook Plant-Based India (published August 2022), which was named one of The New York Times Best Cookbooks of 2022 and nominated for a 2023 James Beard Foundation Book Award.

As a doctor, what do you envision as the way forward to encourage people to include more fruits and vegetables into their diets?

As a primary care physician, I believe one way forward to encouraging more consumption of fruits and vegetables is to educate the medical community about the merits of a plant-based diet. When patients hear this information from their physicians and other medical providers, I think many can be receptive to it. I think it is more important now than ever to combat the misinformation on diets and nutrition that pervades social and traditional media.

What key message would you like to share with our audience about nutrition and public health?

Nutrition plays an incredibly powerful role in public health. Beyond increasing awareness of the benefits of a plant-based diet, I believe more resources should be directed toward the widespread access to healthful foods and addressing food deserts. Furthermore, I look forward to the day that medical providers are equally equipped to counsel their patients regarding nutrition as they do pharmacotherapy.

What are some plant-based ingredients and vegan dishes you would like to highlight as traditional to your culture?

The vast array of spices and legumes is most definitely a highlight of Indian culture. These ingredients are not only incredibly nutrient-dense, but they form the backbone of plant-based Indian cuisine. Some of my favorite spices include cumin, coriander, fennel, and turmeric, and some of my favorite legumes include mung beans, black chickpeas, and red lentils––all of which are used widely throughout Indian cuisine.

What does AAPI Month mean to you, and how is it significant to the work you do?

AAPI Month draws attention to the incredibly diverse and vibrant AAPI community. For me, it means learning from those around me and sharing more about my culture and heritage with others. We are all the better when we share and grow together.

Please tell us a little bit about your book,

Plant-Based India

.

Please tell us a little bit about your book,

Plant-Based India

.Plant-Based India documents my culinary heritage—the recipes and techniques that have been passed down in my family for generations. It highlights plant-forward aspects of Indian cuisine, in a way that is accessible to the western kitchen and pantry. My cookbook includes more than 100 hearty Indian and Indian-inspired recipes that I developed and photographed myself.

Gājjar No Halvo Baked Oatmeal

Serves 2 to 4

Prep Time 10 minutes

Cook Time 30 minutes

Gājjar no halvo, also known as gājjar kā halwā, is a carrot-based dessert made of grated carrots slowly cooked in milk and sugar. Its comforting warmth will soothe you on any cold day. A nutritious dessert that’s rich in anti-inflammatory compounds, fiber, and omega-3 fatty acids, this dish beats out even the heartiest breakfasts. Popping everything in the oven makes the process much simpler. Feel free to top with warmed nondairy milk and a drizzle of maple syrup after baking to make the consistency thinner and to sweeten it.

Ingredients

1 cup (100 g) old-fashioned rolled oats2 tablespoons ground flax seeds1 tablespoon chia seeds1½ teaspoons ground cinnamon½ teaspoon ground ginger½ teaspoon ground cardamomPinch of grated nutmeg1½ cups (360 ml) unsweetened soy milk or other nondairy milk2 ripe bananas, mashed (about ¾ cup/180 g)2 carrots, grated (about ¾ cup/75 g)5 Medjool dates, finely chopped (about ½ cup/75 g)1 teaspoon vanilla extract or vanilla bean paste⅓ cup (40 g) chopped raw nuts, such as almonds, pistachios, or walnutsUnsweetened soy milk, warmedPinch of ground cinnamonInstructions

Preheat the oven to 350°F (175°C).Mix together the oats, flax, chia, cinnamon, ginger, cardamom, and nutmeg in a large bowl until well combined.Add the soy milk, bananas, carrots, dates, vanilla, and half of the chopped nuts, and mix until thoroughly combined.Transfer the mixture to an 8 to 9-inch (20 to 23 cm) round, square, or oval baking dish. Sprinkle with the remaining nuts and bake until the oats and carrots are tender, about 30 minutes.Serve warm with a bit of warmed soy milk and a pinch of ground cinnamon. Keep leftovers in the refrigerator for a few days and reheat with more milk as needed.Recipe from Plant-Based India: Nourishing Recipes Rooted in Tradition © Dr. Sheil Shukla, 2022. Reprinted by permission of The Experiment. Available everywhere books are sold. theexperimentpublishing.com

For more from Dr. Shukla, check out www.sheilshukla.com and @plantbasedartist on Instagram.