Rachel Aaron's Blog, page 16

May 27, 2015

Writing Wednesdays: How Long Should Your Story Be?

Woohoo! It's hump day. Time for another Writing Wednesdays post!

Today I'm talking about wordcounts and how I decide how long a book should be. First though, some announcements, starting with the most obvious, which is that the blog has been updated with a new look and features, including the badass Marci art that will soon be a cover for my Heartstriker sequel, ONE GOOD DRAGON DESERVES ANOTHER. Please let me know what you think or if there's anything else you'd like to see added. I'm in the process of updating my website to be at least 20% cooler, too. We're just upping the cool all around!

Second, awesome Fantasy author Lindsay Buroker asked me to come on the SFF Marketing Podcast, and I did! And it was great! Awesome questions covering 2k to 10k as well as my experiences with marketing my books both from my trad published side and my own efforts with my indie titles. I was also a giant nerd, but what else could you expect? It's me. \_(ツ)_/¯

Anyway, you can listen or watch the whole thing for free here: SFFMP 32: Traditional Publishing, Indie Publishing, and Writing More Words Per Day with Rachel Aaron.

Enjoy!

And now, without further ado, here's what you're actually (hopefully) here to read:

Writing Wednesdays: How Long Should Your Story Be?

Way back in the ancient times when I was first trying to break into publishing, there were hard and fast rules about how long a story should be (70k for Romance and Thrillers, 80-100k for Fantasy with a ceiling of 120k, etc.). The reason for this was because, back when every book was released in print, these were the word counts that let a publisher publish your book inside the acceptable printing cost to cover price ratio needed to make a profit.

Back in the days of print dominance, these strict word counts made a lot of sense even outside of a publisher's profit and loss sheets. Too long, and your book would cost too much to produce, which would in turn force up the cover price past what readers were willing to pay. Too short, and your book would look tiny on the shelf, creating the perception of a rip off (who wants to pay $6 for that pamphlet of a book?!).

But with the rising dominance of ebooks, hard word counts have become far less important. Longer books still cost more to produce since they just take longer to edit and proofread, but the production cost difference between a monster tome and a short quick read is much less of an issue than it used to be, especially if you're covering the cost of the book yourself. Also, since all books are now just links on a eReader, readers can't see them next to each other on the shelf, which eliminates the stigma against overly short or long books. Every book is judged equally by its title, cover, and blurb.

As writers, this shift away from the classic hard and fast rules on novel length gives us enormous freedom. Now, at last, we can focus on telling exactly the story we want in the best way possible without worrying if we're going over or under a limit. By that same turn, though, it's also enough rope to hang ourselves, because even though we don't have to worry so much about print lengths anymore (or at all if you're publishing in ebook only), there is definitely still a perception of how long a novel should be among readers.

This perception of what is or isn't an acceptable length for a novel varies by genre, and failing to fit inside it can lead to some nasty reviews, even from readers who loved your book otherwise. This is especially true with books that run too short, because when a reader pays for something, they expect to get their money's worth.

So how can we as writers avoid this problem? Well, the simplest solution is to just stick to the old word counts, the standardized lengths the publishing industry has been teaching readers to expect for decades. Personally, though, I hate the constraint of hard word counts. I believe that the word count should serve the story, not the other way around. That said, though, I'm a commercial writer. If I want to keep selling books (and I do), I have to write for my market, which means respecting what my readers want and expect when it comes to length.

So how do I balance the book length I want verses the book length they expect? Also, how can you tell if a story is a stand alone of it if needs to be multiple books? These aren't questions that have definitive answers, but, like everything in writing, determining the right balance for your book all comes down to skill, planning, and execution.

Step 1: Figure out how long your book is going to be, and if that's a problem.

When I sit down to write a new story, the very first thing I think about is how long it's going to be. Because I love to world build, I'll often come to a book with enough stuff to write something that's five or ten times larger than what I really need. Determining what belongs and what needs to stay in the background is where the art part of writing comes in. It's not really a question of can, but of should. Sure I can write more, but should I? Is adding more plot or information actually going to help my story, or it just going to drag it down?

These are calls that only I as the author can make, and I've found the best way to decide which of my ideas is worthy of making the cut into the final story is to try and think like a reader. I can't speak to you, but I know that for me, Writer!Rachel and Reader!Rachel have very different priorities. Writer!Rachel thinks all her ideas are awesome and can't wait to cram everything in, while Reader!Rachel just wants the story to move ahead at the speed of maximum excitement.

This is why, when I'm plotting a book, I always try to start at the barest minimum story needed to get from the beginning to the end. I can always add more scenes later, but the bones of the plot don't change. A note here; if you can't figure out which plot line or lines are your main story, that's a warning flag that your book might be rambling. An author has to know better than anyone what story exactly they're trying to tell, otherwise your book will be a mess. So if you're not sure, figure it out. You can always change your mind later.

Once I have the bare bones of my plot down, I try to figure out how many words I think it'll take to write just what I've got to determine the minimum length of my book. Now, obviously, the accounting here will vary enormously from writer to writer just based on style, so if you don't already have a good idea of how long your scenes run, I suggest going back to something you wrote earlier that you're proud of and figuring out your average scene length. Once you've got that, you can look at a plot, make a rough estimation of how many scenes it'll break down into, and then multiply by your average scene word count to get a very ballpark idea of how long the finished book will be. If that number is shorter than 100k, you can most likely fit everything you've got into a single book. If it's higher than 100k, you know you're going to end up with either a long book, or a book that might need to be split in half. Even with ebooks, unless you're writing epic fantasy, most readers are leery of 200k+ books, and publishers are VERY skeptical about taking them on. Even, if you're self publishing, books over 200k, or even 150k, can be a bad bet since you're going to be paying to edit what's essentially two books worth of content for only one title's worth of profit.

Considerations like this are why taking the time to consider your final word count before you start writing is so important. It is infinitely easier to cut/add scenes, or to break what you thought was going to be one book into two, before you've invested months of your time in the text. Even if you're a pantser instead of a plotter, taking a moment to critically think about what you'd like the final form of your story to look like can be the difference between finishing up with a novel that's spot on for where you want to be, and finishing up with a novel that you'll now have to fatten up or drastically cut down.

Step 2: Filling in the rest.

Now that I've got the bare bones of your book, it's time to flesh out the rest of me story. Again, this is a process that involves balancing my reader and writer minds. As always, Writer!Rachel has a million things she wants to add, but while that's exciting, the question I always try to ask is would Reader!Rachel care? Does all this extra stuff make the story more exciting/dramatic/engaging, or is it dead weight?

Again, making the call as to what scenes are writer ego and which are actually awesome is part of the art of being a good writer, and should always be carefully considered. Personally, I try to err on the side of less is more. Like Eli, my motto is "my stones have a 2 bird minimum," which means anything I put in my books has to serve at least two purposes. For example, if I have a character talk at length abut her backstory, those words have to do more than just tell her story. Whatever information she's revealing also needs to help build the larger world of the book, or foreshadow future plot events, or name drop other important characters in the setting. It can't just be a girl talking about her childhood. Or, rather, it can, but again, you've only got so many words in your book. Why waste them doing only one thing?

Help! My book's too long!

If your word count is bloating out of control, but you're not sure why, my advice is to step back and re-focus on the story you're telling right now in this book. Find your main plot line, and make sure it works. Everything else can be added or subtracted later, but your central story has to be coherent, clear, and properly executed if your book is going to be successful. Otherwise it's just a bunch of scenes in a line. Find your main plot and stick to it, cut anything else that's not pulling its weight.

If you do know your main plot, but you're still having trouble making it fit because you need to include way more background information than you have room for, that may be a sign you need to start your book earlier in the story of your world and actually show some of that backstory on the page. Or, if that doesn't work, you could just try starting with at a simpler point for your first book and save the huge complicated stuff for later in the series when your reader is more comfortable/invested.

Finally, if you've got a tight focus on your main story and your book is still larger than you think it should be, you can always go back through and tighten up the individual sentences. Even if you only cut 500 words per chapter, that's still 5k in a ten chapter book/10k from a twenty chapter book, not to mention doing this will often make your writing tighter and therefore better over all. I do this with every book I write.

And if all of those still aren't enough, it might just be time to embrace your larger book. :)

Help! My book's too short! I have to confess, this is an issue I don't generally have. As you might guess from my blog posts, excessive brevity is not my problem. That said, I've read several books that were way shorter than they felt like they should be, and every time, it was because the author made things too easy on their characters.

So if your book is coming in under where you feel it should be, look back and see if you can make life harder on your heroes. Make the bad guy smarter, make the barrier higher, give them bad luck. I'm not saying go overboard into full on sadism, but characters aren't in a book to have a good time. Suffering, struggle, and conflict are the soul of good plots and deep characters, so do whatever you can to make your characters fight for every inch within what's reasonable for your world, and not only will you end up with a better word count, you'll add real depth to your story.

Alternately, you can also expand your book by giving the villain and side characters more development. The trick to this is that the development has to go somewhere. You can't build a character up into someone we're really invested in and then have him go out like a punk. If you're going to get a reader invested, you have to make that investment pay off, or you're just wasting everyone's time. But if you can build up a character and make that pay off at the end (for example, humanizing a villain only to then have his own human weaknesses--such as an inability to let go of anger--be his ultimate downfall at the end), you'll come out with a really great addition to your book.

And again, if you try everything and your book's still too short, maybe you just wrote a novella, which is totally fine.

And that's it!

Thanks for reading! I hope these tricks I've learned help you write the book that's exactly the right length for your story and your market. Ultimately, though, whatever your final word count, the only thing that really matters is that you end up with a book you're proud of and readers will love. Sometimes, books just come out weirdly sized, and no matter what you do, you can't make them fit, and that's okay. So long as the story is good and the writing is tight, the length of the book is ultimately a secondary concern.

And thus concludes this week's Writing Wednesday! Come back next week for a new craft topic, and if you've got a specific issue you'd like me to cover, leave it in the comments below. If you missed a post, you can see them all by clicking the "Writing Wednesday" label (or the general "writing" label, which links to all my writing essays going back to 2012) at the bottom of this post.

Thank you as always for reading, and happy writing!

- Rachel

Today I'm talking about wordcounts and how I decide how long a book should be. First though, some announcements, starting with the most obvious, which is that the blog has been updated with a new look and features, including the badass Marci art that will soon be a cover for my Heartstriker sequel, ONE GOOD DRAGON DESERVES ANOTHER. Please let me know what you think or if there's anything else you'd like to see added. I'm in the process of updating my website to be at least 20% cooler, too. We're just upping the cool all around!

Second, awesome Fantasy author Lindsay Buroker asked me to come on the SFF Marketing Podcast, and I did! And it was great! Awesome questions covering 2k to 10k as well as my experiences with marketing my books both from my trad published side and my own efforts with my indie titles. I was also a giant nerd, but what else could you expect? It's me. \_(ツ)_/¯

Anyway, you can listen or watch the whole thing for free here: SFFMP 32: Traditional Publishing, Indie Publishing, and Writing More Words Per Day with Rachel Aaron.

Enjoy!

And now, without further ado, here's what you're actually (hopefully) here to read:

Writing Wednesdays: How Long Should Your Story Be?

Way back in the ancient times when I was first trying to break into publishing, there were hard and fast rules about how long a story should be (70k for Romance and Thrillers, 80-100k for Fantasy with a ceiling of 120k, etc.). The reason for this was because, back when every book was released in print, these were the word counts that let a publisher publish your book inside the acceptable printing cost to cover price ratio needed to make a profit.

Back in the days of print dominance, these strict word counts made a lot of sense even outside of a publisher's profit and loss sheets. Too long, and your book would cost too much to produce, which would in turn force up the cover price past what readers were willing to pay. Too short, and your book would look tiny on the shelf, creating the perception of a rip off (who wants to pay $6 for that pamphlet of a book?!).

But with the rising dominance of ebooks, hard word counts have become far less important. Longer books still cost more to produce since they just take longer to edit and proofread, but the production cost difference between a monster tome and a short quick read is much less of an issue than it used to be, especially if you're covering the cost of the book yourself. Also, since all books are now just links on a eReader, readers can't see them next to each other on the shelf, which eliminates the stigma against overly short or long books. Every book is judged equally by its title, cover, and blurb.

As writers, this shift away from the classic hard and fast rules on novel length gives us enormous freedom. Now, at last, we can focus on telling exactly the story we want in the best way possible without worrying if we're going over or under a limit. By that same turn, though, it's also enough rope to hang ourselves, because even though we don't have to worry so much about print lengths anymore (or at all if you're publishing in ebook only), there is definitely still a perception of how long a novel should be among readers.

This perception of what is or isn't an acceptable length for a novel varies by genre, and failing to fit inside it can lead to some nasty reviews, even from readers who loved your book otherwise. This is especially true with books that run too short, because when a reader pays for something, they expect to get their money's worth.

So how can we as writers avoid this problem? Well, the simplest solution is to just stick to the old word counts, the standardized lengths the publishing industry has been teaching readers to expect for decades. Personally, though, I hate the constraint of hard word counts. I believe that the word count should serve the story, not the other way around. That said, though, I'm a commercial writer. If I want to keep selling books (and I do), I have to write for my market, which means respecting what my readers want and expect when it comes to length.

So how do I balance the book length I want verses the book length they expect? Also, how can you tell if a story is a stand alone of it if needs to be multiple books? These aren't questions that have definitive answers, but, like everything in writing, determining the right balance for your book all comes down to skill, planning, and execution.

Step 1: Figure out how long your book is going to be, and if that's a problem.

When I sit down to write a new story, the very first thing I think about is how long it's going to be. Because I love to world build, I'll often come to a book with enough stuff to write something that's five or ten times larger than what I really need. Determining what belongs and what needs to stay in the background is where the art part of writing comes in. It's not really a question of can, but of should. Sure I can write more, but should I? Is adding more plot or information actually going to help my story, or it just going to drag it down?

These are calls that only I as the author can make, and I've found the best way to decide which of my ideas is worthy of making the cut into the final story is to try and think like a reader. I can't speak to you, but I know that for me, Writer!Rachel and Reader!Rachel have very different priorities. Writer!Rachel thinks all her ideas are awesome and can't wait to cram everything in, while Reader!Rachel just wants the story to move ahead at the speed of maximum excitement.

This is why, when I'm plotting a book, I always try to start at the barest minimum story needed to get from the beginning to the end. I can always add more scenes later, but the bones of the plot don't change. A note here; if you can't figure out which plot line or lines are your main story, that's a warning flag that your book might be rambling. An author has to know better than anyone what story exactly they're trying to tell, otherwise your book will be a mess. So if you're not sure, figure it out. You can always change your mind later.

Once I have the bare bones of my plot down, I try to figure out how many words I think it'll take to write just what I've got to determine the minimum length of my book. Now, obviously, the accounting here will vary enormously from writer to writer just based on style, so if you don't already have a good idea of how long your scenes run, I suggest going back to something you wrote earlier that you're proud of and figuring out your average scene length. Once you've got that, you can look at a plot, make a rough estimation of how many scenes it'll break down into, and then multiply by your average scene word count to get a very ballpark idea of how long the finished book will be. If that number is shorter than 100k, you can most likely fit everything you've got into a single book. If it's higher than 100k, you know you're going to end up with either a long book, or a book that might need to be split in half. Even with ebooks, unless you're writing epic fantasy, most readers are leery of 200k+ books, and publishers are VERY skeptical about taking them on. Even, if you're self publishing, books over 200k, or even 150k, can be a bad bet since you're going to be paying to edit what's essentially two books worth of content for only one title's worth of profit.

Considerations like this are why taking the time to consider your final word count before you start writing is so important. It is infinitely easier to cut/add scenes, or to break what you thought was going to be one book into two, before you've invested months of your time in the text. Even if you're a pantser instead of a plotter, taking a moment to critically think about what you'd like the final form of your story to look like can be the difference between finishing up with a novel that's spot on for where you want to be, and finishing up with a novel that you'll now have to fatten up or drastically cut down.

Step 2: Filling in the rest.

Now that I've got the bare bones of your book, it's time to flesh out the rest of me story. Again, this is a process that involves balancing my reader and writer minds. As always, Writer!Rachel has a million things she wants to add, but while that's exciting, the question I always try to ask is would Reader!Rachel care? Does all this extra stuff make the story more exciting/dramatic/engaging, or is it dead weight?

Again, making the call as to what scenes are writer ego and which are actually awesome is part of the art of being a good writer, and should always be carefully considered. Personally, I try to err on the side of less is more. Like Eli, my motto is "my stones have a 2 bird minimum," which means anything I put in my books has to serve at least two purposes. For example, if I have a character talk at length abut her backstory, those words have to do more than just tell her story. Whatever information she's revealing also needs to help build the larger world of the book, or foreshadow future plot events, or name drop other important characters in the setting. It can't just be a girl talking about her childhood. Or, rather, it can, but again, you've only got so many words in your book. Why waste them doing only one thing?

Help! My book's too long!

If your word count is bloating out of control, but you're not sure why, my advice is to step back and re-focus on the story you're telling right now in this book. Find your main plot line, and make sure it works. Everything else can be added or subtracted later, but your central story has to be coherent, clear, and properly executed if your book is going to be successful. Otherwise it's just a bunch of scenes in a line. Find your main plot and stick to it, cut anything else that's not pulling its weight.

If you do know your main plot, but you're still having trouble making it fit because you need to include way more background information than you have room for, that may be a sign you need to start your book earlier in the story of your world and actually show some of that backstory on the page. Or, if that doesn't work, you could just try starting with at a simpler point for your first book and save the huge complicated stuff for later in the series when your reader is more comfortable/invested.

Finally, if you've got a tight focus on your main story and your book is still larger than you think it should be, you can always go back through and tighten up the individual sentences. Even if you only cut 500 words per chapter, that's still 5k in a ten chapter book/10k from a twenty chapter book, not to mention doing this will often make your writing tighter and therefore better over all. I do this with every book I write.

And if all of those still aren't enough, it might just be time to embrace your larger book. :)

Help! My book's too short! I have to confess, this is an issue I don't generally have. As you might guess from my blog posts, excessive brevity is not my problem. That said, I've read several books that were way shorter than they felt like they should be, and every time, it was because the author made things too easy on their characters.

So if your book is coming in under where you feel it should be, look back and see if you can make life harder on your heroes. Make the bad guy smarter, make the barrier higher, give them bad luck. I'm not saying go overboard into full on sadism, but characters aren't in a book to have a good time. Suffering, struggle, and conflict are the soul of good plots and deep characters, so do whatever you can to make your characters fight for every inch within what's reasonable for your world, and not only will you end up with a better word count, you'll add real depth to your story.

Alternately, you can also expand your book by giving the villain and side characters more development. The trick to this is that the development has to go somewhere. You can't build a character up into someone we're really invested in and then have him go out like a punk. If you're going to get a reader invested, you have to make that investment pay off, or you're just wasting everyone's time. But if you can build up a character and make that pay off at the end (for example, humanizing a villain only to then have his own human weaknesses--such as an inability to let go of anger--be his ultimate downfall at the end), you'll come out with a really great addition to your book.

And again, if you try everything and your book's still too short, maybe you just wrote a novella, which is totally fine.

And that's it!

Thanks for reading! I hope these tricks I've learned help you write the book that's exactly the right length for your story and your market. Ultimately, though, whatever your final word count, the only thing that really matters is that you end up with a book you're proud of and readers will love. Sometimes, books just come out weirdly sized, and no matter what you do, you can't make them fit, and that's okay. So long as the story is good and the writing is tight, the length of the book is ultimately a secondary concern.

And thus concludes this week's Writing Wednesday! Come back next week for a new craft topic, and if you've got a specific issue you'd like me to cover, leave it in the comments below. If you missed a post, you can see them all by clicking the "Writing Wednesday" label (or the general "writing" label, which links to all my writing essays going back to 2012) at the bottom of this post.

Thank you as always for reading, and happy writing!

- Rachel

Published on May 27, 2015 04:51

May 20, 2015

Writing Wednesdays: My POV on POVs - Whom to Use, and When

So, as you see, we're doing some big work on the blog. New posts, a tag system, more subscription options, all sorts of stuff! But the biggest thing we're adding is Writing Wednesday!

Now, instead of waiting weeks for me to fall out of my novel, I'll have new writing posts going up every Wednesday covering plot, characters, pacing, story structure, and pretty much anything else I've run into as a writer. Have a writing problem you'd like to talk about? Put it in the comments below! Today, by popular request, I'm talking about how I handle POV, so enough business. Let's get started!

Writing Wednesdays: My POV on POVs - Whom to Use, and When

(Note: If you don't know what a POV is, go here for a great breakdown.)

If you've ever read any of my Fantasy (especially my Eli Monpress books), you know I am the queen of multiple POVs. I love them. I love how they let you show the reader different parts of the story at different times to increase tension or give a different point of view. This is why the Paradox books drove me crazy sometimes, because it was in First Person, which felt like being stuck in a canyon. All this amazing stuff was going on in the background, and I couldn't jump over to show it. Let me tell you, it took a lot of narrative acrobatics to figure out how to fit all that stuff in without the luxury of POV switches.

Fortunately for me, third person writing (my favorite style) is all about the POV switch! That said, though, you can't go too crazy. POV switches are a powerful narrative tool, but each perspective you jump to adds a layer of complexity and weight to your novel, and that can get out of hand very quickly. So how do I decide when to jump POVs and when to stay? Or which character gets a POV and which stays to the side?

When I'm deciding on a POV character, my most important considerations are 1) who's got the most interesting viewpoint, and 2) information control. Obviously, you always want to describe a scene through the eyes of the character who's viewpoint is the most exciting for the reader. Think of your scene like a play. Your reader has done you the great honor of going to your show, are you going to stick them in the nosebleed section? Or behind the curtain with the catering? No! You want your reader in the front row, or even on the stage. Whatever POV is the best seat in the house, that's where you want your reader.

But sometimes you can't do this. Sometimes, the character who would otherwise have the most interesting view of a scene is off limits for you narratively because they simply know too much, and if we put the reader in their head, they'll give the whole game away. This is where my second consideration, information control, comes in.

Controlling how much the reader knows is vital to keeping the tension in a story. Your secrets (plot, world, and character) are your big reveals as an author. You can't just have characters blabbing about them and spoiling the surprise. Speaking from personal experience, I had a huge problem with this in my Eli Monpress books, and it's the reason Eli is the POV character in only about 40% of the scenes, despite being the titular character of the series. He simply knew too much about the secrets of the world. He was fine for some scenes, but there were situations in the book where, if I wrote them from his perspective, his natural train of thought as a character would give the whole game away, and all the mystery and tension I'd worked so hard to build up over multiple novels would fall flat. His entire thought process was a spoiler, basically, which made it almost impossible to give him the narrative POV in delicate scenes.

Getting around this problem is one of the main reasons The Legend of Eli Monpress employs such an enormous number of POV characters. In the first book alone, I had Eli, Miranda, Josef, both villains, the king, various spirits, a nameless child, and a rat. Oh, and I also had a scene in omniscient 3rd person where the POV watched two very big power players have a conversation like an invisible camera.

So, as you see, you have a lot of lot of options when it comes to POV. Personally, I'm a huge fan of going wherever I need to go to get the best story, which sometimes means picking some pretty weird POVs. I always try to show events from the most interesting light, and I'm not afraid to use out of the box view points to get there.

That said, though, employing multiple POVs, especially weird ones, can be a risky move. If you do it badly and confuse the reader, they'll put your book down faster you can say Stop!, and then you've lost them forever. Fortunately, it's actually pretty easy to write solid POV switches that won't piss off your readers by following a few simple guidelines.

1) Avoid head hopping.

Seriously, people hate this. When readers gripe about POV, this is usually what they're talking about, and I can totally understand why. Head hopping happens when you shift POV inside a scene without breaking it first or giving the reader some kind of warning. You literally just "hop" into another head. I've read books where the POV was pinging between two characters having a conversation like they were playing tennis, sometimes even within the same paragraph, and it was horrible.

I try to avoid saying never do something in writing, because invariably, the second I say it, I'll read a book where the author pulled that exact thing off in spades. Good writing is entirely about execution, and literally nothing is off limits if you can do it well. THAT SAID, 99.9% of the time, head hopping is a terrible decision that will get you nothing but angry reviews, Not only is jumping back and forth between people's heads super confusing for your audience, it also weakens their personal connection to your characters since it ruins all sense of being inside someone's private thoughts. If you really think you can pull it off, more power to you, but my advice is to stay away.

2) If you're not going back to a POV character, don't give them a name.

I know this seems weird. If we're in someone's head, surely we must need to know who they are, right? But names represent heavy lifting for your audience. Readers feel like they need to remember named characters, which means you have to be careful with them lest your book start feeling like a quiz. Fortunately, very few minor characters actually need names.

For example, let's say you have a scene where a bystander witnesses something important, like a murder. If that character's only job in the book was to be a window for the reader, and they're never coming back except maybe as someone the MC interrogates later, then that character only needs a broad descriptor, like "the fisherwoman" or "the old man in the hat." Something you can give your reader as a quick identifying marker without making them remember yet another name. This sort of shorthand label identification is much easier on your readers, and that, in turn, makes them much more amiable to following your story through multiple POVs.

Of course, you could also just do the witness scene from 3rd person omniscient perspective (ie. the "floating eyeball" or "camera in the sky" perspective) and not worry about characters at all, but 3rd person omniscient is famously one of the hardest writing styles to pull off. It's super easy to mess up and write a movie voiceover of events instead of an actual scene readers will care about. I do employ 3rd omniscient in my novels, but my personal rule is that, if I'm writing more than a few paragraphs, I have to be in someone's head. But, again, this is a personal preference. If you feel you can ace 3rd omniscient, go for it!

3) If you do give a POV character a name, make sure they have at least two POV scenes.

The logic here is the same as above. If you're going to ask your reader to invest in remembering the name of a POV character, it's a good idea to reward that investment with at least two scenes so they don't feel like they did all that memorization for nothing. The only time I don't follow this rule is when I'm writing POV scenes for very powerful, distant characters that the reader is SUPER EXCITED to learn more about. These POV scenes are rare treats, and if you play them up properly beforehand (and dole them out very infrequently to keep them special), your reader will gobble them up without any extra work on your part.

4) Avoid wild swings in writing style when switching POVs.

Changing your style between POVs is a classic gimmick to create distinct voices for your characters. Like every gimmick, though, it gets tired if you use it too much. This doesn't mean you shouldn't give each character their own distinct voice and personality, obviously, but if you're going to be switching POVs frequently, it's probably a good idea not to do one in a heavy Scottish brogue, one in second person, one in all caps, one in Ye Olde English, and so forth. Just use common sense and think of your reader first and you should be fine.

5) When possible, choose the POV character who knows the least/has the most to lose.

This is more of a trick than a rule, but a great way to feed information to your audience without resorting to an info dump is to choose a POV character who is as ignorant about the scene as the reader is. If you have a scene with two character, and you have a POV choice between a character who knows everything and a character who knows nothing, going with the person who's learning along with the reader is a fantastic, dead easy way to combine exposition with character development.

Likewise, if you want to make sure a scene is super exciting and tense, just tell it from the POV of the character who has the most on the line in the situation (for example, doing an execution scene from the POV of the character being executed). When you put your POV in the head of the character who's got the most to lose in a scene, not only do you get great tension, but that character's anxiety will transfer to the reader, giving you a super intense scene without you really having to do more than set up the stakes.

Both of these tricks are great ways to make your POVs do double duty in your novels. By being smart in your POV choices, you can turn what would otherwise be weighty narrative work (exposition, character introduction, world building) into a natural extension of the POV character's own internal learning and struggles. It's some serious author magic when it comes together. Highly recommended!

6) Save the omniscient POVs for special occasions.

I went over this briefly a few points up, but it bares mention again. Omniscient third person is a POV where you're not in anyone's head. The scene is presented as though we are an invisible eyeball, passively watching events unfold below. It's a great tactic if you want to show something huge that the characters would otherwise be unable to observe, like a fissure opening up beneath the Earth's crust, or a meeting between two gods who rule the universe.

Unfortunately, the very passive, impersonal nature that makes omniscient narration so great for showing big things makes it terrible at showing everything else. There's no investment, no character, and therefore, no engagement. It's a highly detached viewpoint, and that means your reader is detached as well, which can be really bad if pushed for long periods of time. Used wisely and sparingly, though, 3rd person omniscient is a great tool for showing your reader something the characters can't see/don't know, which is a tool every author needs in their arsenal.

And that's how I choose POV! I know all the above seems like a lot, but as one multi-POV addict to another, I've found following these guidelines allows me to employ an enormous range of alternating viewpoints without overloading my reader. As with everything in writing, POV is all about execution, but if you're clever and keep your reader in mind, you can get away with a stupidly enormous number of POVs without ever having a complaint.

And with that, we come to the end. I really hope you enjoyed the first of what (fingers crossed) will be many Writing Wednesdays! Again, if you have a question or a writing topic you'd like me to go into, please post it below. As always, thank you for reading, and happy writing!

- Rachel

Now, instead of waiting weeks for me to fall out of my novel, I'll have new writing posts going up every Wednesday covering plot, characters, pacing, story structure, and pretty much anything else I've run into as a writer. Have a writing problem you'd like to talk about? Put it in the comments below! Today, by popular request, I'm talking about how I handle POV, so enough business. Let's get started!

Writing Wednesdays: My POV on POVs - Whom to Use, and When

(Note: If you don't know what a POV is, go here for a great breakdown.)

If you've ever read any of my Fantasy (especially my Eli Monpress books), you know I am the queen of multiple POVs. I love them. I love how they let you show the reader different parts of the story at different times to increase tension or give a different point of view. This is why the Paradox books drove me crazy sometimes, because it was in First Person, which felt like being stuck in a canyon. All this amazing stuff was going on in the background, and I couldn't jump over to show it. Let me tell you, it took a lot of narrative acrobatics to figure out how to fit all that stuff in without the luxury of POV switches.

Fortunately for me, third person writing (my favorite style) is all about the POV switch! That said, though, you can't go too crazy. POV switches are a powerful narrative tool, but each perspective you jump to adds a layer of complexity and weight to your novel, and that can get out of hand very quickly. So how do I decide when to jump POVs and when to stay? Or which character gets a POV and which stays to the side?

When I'm deciding on a POV character, my most important considerations are 1) who's got the most interesting viewpoint, and 2) information control. Obviously, you always want to describe a scene through the eyes of the character who's viewpoint is the most exciting for the reader. Think of your scene like a play. Your reader has done you the great honor of going to your show, are you going to stick them in the nosebleed section? Or behind the curtain with the catering? No! You want your reader in the front row, or even on the stage. Whatever POV is the best seat in the house, that's where you want your reader.

But sometimes you can't do this. Sometimes, the character who would otherwise have the most interesting view of a scene is off limits for you narratively because they simply know too much, and if we put the reader in their head, they'll give the whole game away. This is where my second consideration, information control, comes in.

Controlling how much the reader knows is vital to keeping the tension in a story. Your secrets (plot, world, and character) are your big reveals as an author. You can't just have characters blabbing about them and spoiling the surprise. Speaking from personal experience, I had a huge problem with this in my Eli Monpress books, and it's the reason Eli is the POV character in only about 40% of the scenes, despite being the titular character of the series. He simply knew too much about the secrets of the world. He was fine for some scenes, but there were situations in the book where, if I wrote them from his perspective, his natural train of thought as a character would give the whole game away, and all the mystery and tension I'd worked so hard to build up over multiple novels would fall flat. His entire thought process was a spoiler, basically, which made it almost impossible to give him the narrative POV in delicate scenes.

Getting around this problem is one of the main reasons The Legend of Eli Monpress employs such an enormous number of POV characters. In the first book alone, I had Eli, Miranda, Josef, both villains, the king, various spirits, a nameless child, and a rat. Oh, and I also had a scene in omniscient 3rd person where the POV watched two very big power players have a conversation like an invisible camera.

So, as you see, you have a lot of lot of options when it comes to POV. Personally, I'm a huge fan of going wherever I need to go to get the best story, which sometimes means picking some pretty weird POVs. I always try to show events from the most interesting light, and I'm not afraid to use out of the box view points to get there.

That said, though, employing multiple POVs, especially weird ones, can be a risky move. If you do it badly and confuse the reader, they'll put your book down faster you can say Stop!, and then you've lost them forever. Fortunately, it's actually pretty easy to write solid POV switches that won't piss off your readers by following a few simple guidelines.

1) Avoid head hopping.

Seriously, people hate this. When readers gripe about POV, this is usually what they're talking about, and I can totally understand why. Head hopping happens when you shift POV inside a scene without breaking it first or giving the reader some kind of warning. You literally just "hop" into another head. I've read books where the POV was pinging between two characters having a conversation like they were playing tennis, sometimes even within the same paragraph, and it was horrible.

I try to avoid saying never do something in writing, because invariably, the second I say it, I'll read a book where the author pulled that exact thing off in spades. Good writing is entirely about execution, and literally nothing is off limits if you can do it well. THAT SAID, 99.9% of the time, head hopping is a terrible decision that will get you nothing but angry reviews, Not only is jumping back and forth between people's heads super confusing for your audience, it also weakens their personal connection to your characters since it ruins all sense of being inside someone's private thoughts. If you really think you can pull it off, more power to you, but my advice is to stay away.

2) If you're not going back to a POV character, don't give them a name.

I know this seems weird. If we're in someone's head, surely we must need to know who they are, right? But names represent heavy lifting for your audience. Readers feel like they need to remember named characters, which means you have to be careful with them lest your book start feeling like a quiz. Fortunately, very few minor characters actually need names.

For example, let's say you have a scene where a bystander witnesses something important, like a murder. If that character's only job in the book was to be a window for the reader, and they're never coming back except maybe as someone the MC interrogates later, then that character only needs a broad descriptor, like "the fisherwoman" or "the old man in the hat." Something you can give your reader as a quick identifying marker without making them remember yet another name. This sort of shorthand label identification is much easier on your readers, and that, in turn, makes them much more amiable to following your story through multiple POVs.

Of course, you could also just do the witness scene from 3rd person omniscient perspective (ie. the "floating eyeball" or "camera in the sky" perspective) and not worry about characters at all, but 3rd person omniscient is famously one of the hardest writing styles to pull off. It's super easy to mess up and write a movie voiceover of events instead of an actual scene readers will care about. I do employ 3rd omniscient in my novels, but my personal rule is that, if I'm writing more than a few paragraphs, I have to be in someone's head. But, again, this is a personal preference. If you feel you can ace 3rd omniscient, go for it!

3) If you do give a POV character a name, make sure they have at least two POV scenes.

The logic here is the same as above. If you're going to ask your reader to invest in remembering the name of a POV character, it's a good idea to reward that investment with at least two scenes so they don't feel like they did all that memorization for nothing. The only time I don't follow this rule is when I'm writing POV scenes for very powerful, distant characters that the reader is SUPER EXCITED to learn more about. These POV scenes are rare treats, and if you play them up properly beforehand (and dole them out very infrequently to keep them special), your reader will gobble them up without any extra work on your part.

4) Avoid wild swings in writing style when switching POVs.

Changing your style between POVs is a classic gimmick to create distinct voices for your characters. Like every gimmick, though, it gets tired if you use it too much. This doesn't mean you shouldn't give each character their own distinct voice and personality, obviously, but if you're going to be switching POVs frequently, it's probably a good idea not to do one in a heavy Scottish brogue, one in second person, one in all caps, one in Ye Olde English, and so forth. Just use common sense and think of your reader first and you should be fine.

5) When possible, choose the POV character who knows the least/has the most to lose.

This is more of a trick than a rule, but a great way to feed information to your audience without resorting to an info dump is to choose a POV character who is as ignorant about the scene as the reader is. If you have a scene with two character, and you have a POV choice between a character who knows everything and a character who knows nothing, going with the person who's learning along with the reader is a fantastic, dead easy way to combine exposition with character development.

Likewise, if you want to make sure a scene is super exciting and tense, just tell it from the POV of the character who has the most on the line in the situation (for example, doing an execution scene from the POV of the character being executed). When you put your POV in the head of the character who's got the most to lose in a scene, not only do you get great tension, but that character's anxiety will transfer to the reader, giving you a super intense scene without you really having to do more than set up the stakes.

Both of these tricks are great ways to make your POVs do double duty in your novels. By being smart in your POV choices, you can turn what would otherwise be weighty narrative work (exposition, character introduction, world building) into a natural extension of the POV character's own internal learning and struggles. It's some serious author magic when it comes together. Highly recommended!

6) Save the omniscient POVs for special occasions.

I went over this briefly a few points up, but it bares mention again. Omniscient third person is a POV where you're not in anyone's head. The scene is presented as though we are an invisible eyeball, passively watching events unfold below. It's a great tactic if you want to show something huge that the characters would otherwise be unable to observe, like a fissure opening up beneath the Earth's crust, or a meeting between two gods who rule the universe.

Unfortunately, the very passive, impersonal nature that makes omniscient narration so great for showing big things makes it terrible at showing everything else. There's no investment, no character, and therefore, no engagement. It's a highly detached viewpoint, and that means your reader is detached as well, which can be really bad if pushed for long periods of time. Used wisely and sparingly, though, 3rd person omniscient is a great tool for showing your reader something the characters can't see/don't know, which is a tool every author needs in their arsenal.

And that's how I choose POV! I know all the above seems like a lot, but as one multi-POV addict to another, I've found following these guidelines allows me to employ an enormous range of alternating viewpoints without overloading my reader. As with everything in writing, POV is all about execution, but if you're clever and keep your reader in mind, you can get away with a stupidly enormous number of POVs without ever having a complaint.

And with that, we come to the end. I really hope you enjoyed the first of what (fingers crossed) will be many Writing Wednesdays! Again, if you have a question or a writing topic you'd like me to go into, please post it below. As always, thank you for reading, and happy writing!

- Rachel

Published on May 20, 2015 07:19

May 19, 2015

Romantic Times 2015 as a non-Romance writer - Why I went, and was it worth it?

Souvenirs! My husband asked me to bring him back

Souvenirs! My husband asked me to bring him back the most Texas thing I could find. Mission accomplished!If you were anywhere near my Twitter feed last week, you're probably more aware than you'd like to be that I was in Dallas, TX for the Romantic Times Book Lover's Convention, one of the biggest Romance genre conventions in the world. I didn't actually know that before I signed up because, ya know, I'm not a Romance author. Even FORTUNE'S PAWN, the most romantic of all my books, only has romance as a sub-plot, and my covers most definitely do not have pretty dresses, leather pants, or rock hard abs. So why did I, an SFF author, go to RT?

Well, in the beginning, I went because Ilona Andrews (whom I already owed a bar's worth of drinks for giving me a great review of FORTUNE'S PAWN on her blog) asked me to be on her Urban Fantasy panel. At that point, I was only vaguely aware of RT as a place where Romance authors went to have epic parties, but when Ilona Andrews asks you to be on a panel, you say yes. So of course, I accepted instantly, and then I scrambled off to the internet to find out what, exactly, I'd signed myself up for.

The answer was a lot more than I expected. RT started as a reader con, but these days it's more of a giant who's who in the Romance writing and publishing world. Everyone, and I do mean everyone--big NY publishers, small presses, self pubbers, Amazon's KDP team, NY Times mega bestsellers, readers, reviewers, fans, bloggers, book store reps, librarians--who has any connection to the Romance genre was packed into a giant hotel meeting and partying and moving through panels in a giant mass of networking fury.

As a mid-list author who is only tangentially connected to Romance, this was a pretty intimidating world to dive into. Other than a few Twitter/email interactions, I knew no one there, and I was constantly worried no one would care about me or my books since, again, I'm only a "Romance Author" by the furthest stretch of the definition. Also, like any giant con, RT was expensive.

Given all that, you can imagine how nervous I was, but I'm happy to report that my RT gamble paid off better than I could have hoped! It was absolutely worth the time and money for me both as an author and a Romance reader. I could gush for hours about all the awesome connections I made and the fun I had, but I think I've fangirled enough for one month, so here's the same information in useful bulleted list format.

WHY YOU SHOULD GO TO RT (for authors):The panels. I think what surprised me the most about RT was how amazingly awesome the panels were. I mean, most cons have decent panels, but these were absolutely stellar. They had panels for craft, marketing, social media, author branding, business, international rights, and a whole host of other topics all led by some of the biggest names in the business. I've been writing professionally since 2009, and I still took over 50 pages of notes, ten of which were from the Tension panel with Patricia Briggs alone. I can't remember the last time I learned so much in such a short period of time. My only regret is that I could only go to one panel at a time. I can't tell you how many times I wished I could split myself because there were two panels I wanted to go to happening at the same time.The networking. As I said, when I got to RT, I knew no one. This was not the case by the time I left four days later. I'm normally pretty nervous about striking up conversations with random strangers, but RT was hands down the friendliest con I've ever been to. Everyone is there to make new connections, and since most of the attendees are also authors and/or people in the publishing industry, you've got a guaranteed topic of conversation in books. Big pub, small pub, self pub: there was so much shop talk going on at all levels, it was pretty much impossible not to meet someone who was interested in your career. Also, if you've only met someone online, this is a great chance to meet them in person over dinner or drinks, and since most of these ladies are tons of fun, it doesn't even feel like work!Meeting other authors. This technically belongs under networking, but I felt it deserves its own segment because while it was great to meet industry people, the true shine of the con for me was getting to meet other authors socially. Writing can be a very lonely life, but when you go to RT, almost everyone you meet is a writer! Sit down at the bar? Writers everywhere! You can be waiting for an elevator and meet someone who not only has your dream writing career, but is happy to talk to you about it. That is GOLD!Getting to talk to Amazon directly. This probably isn't as exciting if you're not involved in self publishing, but one of my favorite panels was the one run by Amazon's head of author relations. The big A showed up at this con ready to rumble, and they put on an impressive show with six people from corporate representing KDP, CreateSpace, and ACX. They didn't give us any truly juicy information (this is Amazon, after all), but they were clearly listening to author concerns and responded with some surprisingly honest and insightful replies. For example, when I asked why can't Amazon show me life time sales, one of the KDP programmers, who was just siting in the audience, piped up and said they were aware of the issue, that it was their fault, and they were working on it, but that it was a big data problem and probably would not be addressed soon. That might not sound like much, but considering it's Amazon, it was way more info than I was expecting. Also, he'd seen and liked the website my husband built to convert KDP spreadsheets into readable graphs! Nerd out!!The exposure. I did two panels over my 4 days at RT, and I was sitting beside Linnea Sinclair, Ilona Andrews, Kresley Cole, Chloe Neill, and Jennifer Estep among others. At the Urban Fantasy panel, I was literally the only non-NYT Bestseller up there, and it was amazing. First of all, it was fantastic getting to speak to all their fans (who are awesome and I hope would become my fans), but even if I didn't convert a single reader....I was sitting at a table with names from my Kindle! These are the ladies who write the books I read for fun! Getting to be up there with them was one of the single coolest experience of my life, and the fact that everyone was so knowledgeable and funny and smart and nice only made it better. Even if you don't get on a panel yourself, the audiences are pretty small, which gives you the chance to talk to the panelists one on one, It really was great.It's freaking fun. THIS CAN NOT BE OVERSTATED. LOOK AT THIS PICTURE:

.@SmartBitches invited me for coffee, gave me a tiara & loved Nice Dragons! Pretty sure this means I owe her my life pic.twitter.com/kXoYmyachF— Rachel Aaron/Bach (@Rachel_Aaron) May 16, 2015Are these the smiles of people at a work convention? YES, YES THEY ARE.

WHY YOU SHOULD GO TO RT (for readers):Do you read romance? Go. Seriously, go. I'm a big Romance reader in my free time, and the fan girl level was off the hook. Your favorite authors are everywhere. I mean, I went to a signing event just to get some my books signed and ended up eating dinner with Tessa Dare! It does not get cooler than that.

Went out to dinner w/ @TessaDare!! Another fangirl life goal achieved!! (at this rate, my plane home will crash) pic.twitter.com/1f1QEtyTXM— Rachel Aaron/Bach (@Rachel_Aaron) May 16, 2015

Now, of course, all of the above assumes you write/are interested in Romantic Fiction. If you don't, I'm sure all of this isn't as exciting to you as it was for me. So, in the spirit of fairness, let's talk about some of the downsides of RT.

WHY RT MIGHT NOT BE FOR YOU:If you don't write love stories, you're probably wasting your time. This isn't to say you have to write Romance capital R to enjoy RT. Like I said, my books are love stories in subplot alone. Still, this is a Romance convention, and Romance readers, though amazingly open in their reading choices, generally want a love story of some sort, so if that's not you, you won't get as much out of RT as an author who writes in the Romance spectrum.It's expensive. This was the #1 complaint I heard about RT. Since it's a professional convention, everyone, even the big names, has to pay to attend. They give you a discount if you're on a panel, but it's still not cheap at a few hundred bucks. Add in airfare, food, and multiple nights at a nice hotel, and the cost adds up quick. I still think it's money well spent, but if you're on a budget, this could definitely be an issue.It's very very VERY social. To get the most out of the networking side of RT, you have to be willing to take the initiative and strike up conversations. Now, I'm an extrovert who talks all the time, so I had no problem with this, but if you're shy or if the thought of meeting lots of people terrifies you, RT will be extremely stressful. I'm not saying you still won't enjoy the panels, but the social half of RT might be more pain than it's worth in your case.It's not really a reader/fan con. There are readers and fans in attendance, but from what I saw, 75% of the people at the con were authors or aspiring authors. That's great for networking and meeting new industry friends, but not so good if your primary goal is to meet or make fans. I don't really think this is a problem since there are plenty of other, non-industry conventions that focus exclusively on readers, but I was surprised by just how writer focused RT was. So, you know, keep that in mind. (That said, if you are going as a Reader/Blogger/Reviewer, this means the con is even more amazing since everyone wants to talk to you and give you free stuff!!)So that's the skinny on RT from the perspective of a mid-list, non-Romance writer. As someone who has her toes in both the self-pub and trad-pub ponds, I think I was in the absolute perfect position to get the most out of this con. The Romance genre is about five years ahead of the rest of the industry when it comes to self publishing, and I learned a lot from listening to the authors there. Smart, smart ladies.

I started this blog in the spirit of sharing my experiences in the hopes that what I learn can help other authors down the line, and that's what this is, too. Whether or not conventions are worth the time and money they take to attend is a question every author has to answer eventually. For me, though, RT was a win. Will I go again? Absolutely. Should you pay to go? Well, selfishly I'd say yes since, if you read my blog, I want to meet you!! Really, though, whether or not RT works for you depends on your situation. If you're a reader who doesn't care about Romance, obviously it's a waste of time. But if you're an author who, like me, writes books with crossover potential into Romance, it could be an amazing experience.

I hope all of this gushing helps you make an informed decision, or at least gets you excited about a freaking fun convention! Good luck to you all, and happy writing/reading!

Yours,Rachel

Published on May 19, 2015 09:28

May 11, 2015

Heartstrikers #2 is FINISHED! (Plus where to find me at RT 2015 and other announcements)

First things first, ONE GOOD DRAGON DESERVES ANOTHER, the sequel to NICE DRAGONS FINISH LAST, is finally done and with the editor!

I still have to actually get the edited manuscript back, make my changes, send it back for copy edits, and then send it to beta readers before the book is ready to come out, but the hard part is over! My aim is to have the book out before the end of summer. I'll post a real date as soon as I know.

I really can not tell you all how excited I am to finally be done with this book. After a YEAR of failing forward, I finally have a novel I am proud of and I know you guys are gonna love. Also, Marci is MVP of the year in this. GO MARCI!

Yes, those cats are plot. Are you excited? CAUSE I'M EXCITED!

Yes, those cats are plot. Are you excited? CAUSE I'M EXCITED!

In other news, I'm going to be at Romantic Times 2015!

I'm pretty sure I've mentioned this before, but with RT just around the corner (as in Wednesday), I thought I'd be good to remind everyone that I'm going to be a guest! Here are the two panels I'm doing:

SCI-FI: COOTIES IN SPACE — How to Keep the Romance Without Losing the Rocketships!

Does sexual tension negate the science? Or can passion and physics coexist? How can authors create intimate relationships in the midst of high-tech, otherworldly science fiction settings — and keep readers of both genres turning pages? Beam up to this panel and find out!

Event Date: Wednesday, May 13, 2015 - 1:15pm to 2:15pm

Captain: Linnea Sinclair

Panelist(s): Rachel Aaron (aka Rachel Bach), Donna Frelick, Monette Michaels (aka Rae Morgan), Sabine Priestley, M. D. Waters

Location: Atrium Level (2nd Floor)

Room: Bryan-Beeman B

PARANORMAL: Happily Forever After — Writing Beyond the Kiss

We all know the story: the hero and heroine fall in love and overcome impossible odds. Finally their love triumphs, they kiss — and then what? With supernatural creatures having such long lifespans, and in some cases being immortal, how do you keep relationships and adventures fresh after that big kiss?

Event Date: Wednesday, May 13, 2015 - 2:30pm to 3:30pm

Captain: Ilona Andrews (aka Ilona and Gordon Andrews)

Panelist(s): Rachel Aaron (aka Rachel Bach), Kresley Cole, Jennifer Estep, Diana Pharaoh Francis, Chloe Neill, Kerrelyn Sparks

Location: Atrium Level (2nd Floor)

Room: Gaston

Why yes, that is me doing a panel with FREAKING IILONA ANDREWS AND KRESLEY COLE! It will be a struggle to talk through the epic fangirl meltdown I'll be having, but I'm going to try.

In addition to these two big official events, I'm also going to be at the book sale and doing one of the meet and greet sessions (UPDATE: I'll be at Fan-Tastic Day on Saturday from 6:15pm to 6:50pm).

I'll also be just, you know, going to the con! So if you're there as well, and you'd like to hang out and have fun/talk shop/whatever, just tweet me and we'll find each other! I'm going to be at the con from Weds to Sunday, so I'll probably be lost and alone. Come be my friend!

And finally, our online tool for making monthly KDP reports actually readable, KDP Plus, has been upgraded and now has its own website!

This was originally a tool my programmer husband made for himself so he could translate my KDP spreadsheets into a format we could actually read/use. It worked so well that we decided to put it online so others could use it, too!

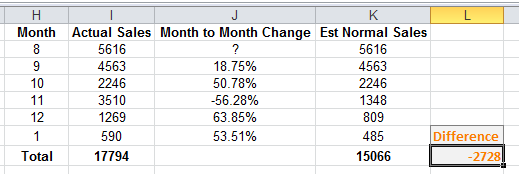

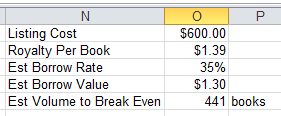

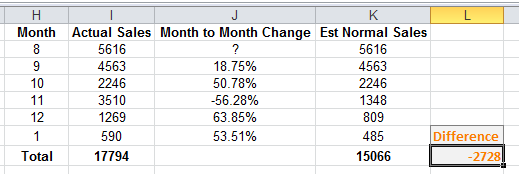

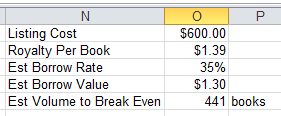

We're still adding features, but right now KDP Plus lets you upload the monthly report spreadsheets you get from Amazon and then see all those numbers translated into readable, interactive graphs that show you things like total lifetime sales by title and how much total money you've made. You know, all that VITAL INFORMATION Amazon should just give you.

So if you're an author who publishes through Amazon, give it a try and let us know what you think! It's free and you don't even have to make an account, so why not?

And that's it for updates! I'm finally free of writing crisis mode, so expect a lot of blog posts in the future. See you all at RT!

I still have to actually get the edited manuscript back, make my changes, send it back for copy edits, and then send it to beta readers before the book is ready to come out, but the hard part is over! My aim is to have the book out before the end of summer. I'll post a real date as soon as I know.

I really can not tell you all how excited I am to finally be done with this book. After a YEAR of failing forward, I finally have a novel I am proud of and I know you guys are gonna love. Also, Marci is MVP of the year in this. GO MARCI!

Yes, those cats are plot. Are you excited? CAUSE I'M EXCITED!

Yes, those cats are plot. Are you excited? CAUSE I'M EXCITED!In other news, I'm going to be at Romantic Times 2015!

I'm pretty sure I've mentioned this before, but with RT just around the corner (as in Wednesday), I thought I'd be good to remind everyone that I'm going to be a guest! Here are the two panels I'm doing:

SCI-FI: COOTIES IN SPACE — How to Keep the Romance Without Losing the Rocketships!

Does sexual tension negate the science? Or can passion and physics coexist? How can authors create intimate relationships in the midst of high-tech, otherworldly science fiction settings — and keep readers of both genres turning pages? Beam up to this panel and find out!

Event Date: Wednesday, May 13, 2015 - 1:15pm to 2:15pm

Captain: Linnea Sinclair

Panelist(s): Rachel Aaron (aka Rachel Bach), Donna Frelick, Monette Michaels (aka Rae Morgan), Sabine Priestley, M. D. Waters

Location: Atrium Level (2nd Floor)

Room: Bryan-Beeman B

PARANORMAL: Happily Forever After — Writing Beyond the Kiss

We all know the story: the hero and heroine fall in love and overcome impossible odds. Finally their love triumphs, they kiss — and then what? With supernatural creatures having such long lifespans, and in some cases being immortal, how do you keep relationships and adventures fresh after that big kiss?

Event Date: Wednesday, May 13, 2015 - 2:30pm to 3:30pm

Captain: Ilona Andrews (aka Ilona and Gordon Andrews)

Panelist(s): Rachel Aaron (aka Rachel Bach), Kresley Cole, Jennifer Estep, Diana Pharaoh Francis, Chloe Neill, Kerrelyn Sparks

Location: Atrium Level (2nd Floor)

Room: Gaston

Why yes, that is me doing a panel with FREAKING IILONA ANDREWS AND KRESLEY COLE! It will be a struggle to talk through the epic fangirl meltdown I'll be having, but I'm going to try.

In addition to these two big official events, I'm also going to be at the book sale and doing one of the meet and greet sessions (UPDATE: I'll be at Fan-Tastic Day on Saturday from 6:15pm to 6:50pm).

I'll also be just, you know, going to the con! So if you're there as well, and you'd like to hang out and have fun/talk shop/whatever, just tweet me and we'll find each other! I'm going to be at the con from Weds to Sunday, so I'll probably be lost and alone. Come be my friend!

And finally, our online tool for making monthly KDP reports actually readable, KDP Plus, has been upgraded and now has its own website!

This was originally a tool my programmer husband made for himself so he could translate my KDP spreadsheets into a format we could actually read/use. It worked so well that we decided to put it online so others could use it, too!

We're still adding features, but right now KDP Plus lets you upload the monthly report spreadsheets you get from Amazon and then see all those numbers translated into readable, interactive graphs that show you things like total lifetime sales by title and how much total money you've made. You know, all that VITAL INFORMATION Amazon should just give you.

So if you're an author who publishes through Amazon, give it a try and let us know what you think! It's free and you don't even have to make an account, so why not?

And that's it for updates! I'm finally free of writing crisis mode, so expect a lot of blog posts in the future. See you all at RT!

Published on May 11, 2015 08:06

April 9, 2015

Where to Start Your Story

FINALLY! A craft post! Allons-y!

Way way back in the halcyon days of last November, someone on my yearly NaNo thread asked me "where do you start your story?" I love this question for a lot of reasons, but mostly because 1) there are so many different places to start any story, and 2) different starts can create entirely different reading experiences, even if the basic plot is the same.

One of the first things I think about when I sit down to actually plot a book is where I'm going to start. As a general rule, the best place to start your story is always wherever things get interesting, BUT (and here's where it gets cool), "where things get interesting" can vary enormously depending on your audience/genre.

Take this plot I just made up:

When she was nine, Mary's family was eaten in a dragon raid. Swearing revenge, she tracks down a knight of the Sacred Order of Dragon Hunters and demands to join. After saying no many times, the knight eventually gives in and agrees to train her. Many years later, Mary has become an amazing Dragon Hunter and is ready to avenge her parents. But when she finally enters the cave of the dragon who took her family so long ago, she discovers everything she thought she knew is wrong, and the real monsters are the ones she never suspected.

Exciting stuff! Now, where would you start this story? There are a lot of good, exciting spots, many of which could work, but which spot is best depends entirely on what kind of story you want to tell.

For example, if I wanted to write a YA, I'd start when the wounded and determined child Mary approaches the knight and demands he teach her to hunt dragons, and then show how she never gives up even when he says no. Once he eventually gives in, I'd show her training and have her finally get to the dragon cave for the mid-book climax, where I'd turn everything on it's head.

On the other hand, if I wanted to write a gritty, dark fantasy about a woman on a path of bloody revenge, I would jump way ahead and start when Mary is already a professional Dragon Hunter doing her final prep for the hunt she's been training her whole life for, only to get in and realize that everything she's assumed up until now is wrong, and things are much darker and more dangerous than simple dragon killing.

Or, if I wanted to play this plot as a straight up Fantasy romance, I could even start the book at the moment when she enters the dragon cave and discovers the dragon she's been training her whole life to kill is actually a super hot dude who's never even heard of her parents and the whole thing was a set up and now they have to work together to find the true killers.

All of these stories would have the same basic set-up plot: girl loses parents to dragon, girl learns dragon hunting for revenge, girl goes to kill dragon and things go wrong. In execution, however, these stories are in fact wildly different in everything from tone to the end secret. All of the above are valid entry points for their particular versions of the story, but what I'm really trying to get across here is that the beginning of a story is not a fixed point. Where you enter a novel depends as much on your audience and what kind of story you're trying to tell as it does on plot.

This isn't to say opening with a hook isn't important. It's vital! Think of the last time you picked up an unknown book. Did you keep reading if the opening page was boring? What about the opening paragraph? Of course not. You put that sucker down, and rightfully so, because the author failed to hook you. This is why asking questions like "where should I start my novel?" is so important, because if you can't keep a reader past the first page, they're not going to be your reader.

Again, though, see above. Not all hooks are the same for all genres and readers. A young girl struggling with the impotent rage of seeing her parents eaten by dragons is a powerful opening, but only if that's the tone you're going for in your book. What's gripping for a gritty Fantasy might turn off readers who're here for a lighthearted dragon/dragon hunter romance and vice-versa. This is another reason why it's so important to know your genre before you start writing. Being published means writing for an audience, and the more you know about how to entertain and hook that audience, the more successful and happy your career will be.

I know all of this seems like a lot to think about for something as simple as an opening scene. Personally, I didn't really start thinking about this stuff until I was multiple novels into my career. I simply wrote what felt like a natural beginning and worked from there. That's not a bad way to write, especially if you have good story instincts, but it can't possibly match the level of control and finesse that comes from actually knowing and thinking about what you're doing.

Good novels don't happen by accident. They are a string of conscious, considered choices. Writing is work, and like any work, the more thought and finesse and skill you put into it, the better the end product becomes.

I hope this post helps you find new ways to think about how best to begin your own books! As always, thank you for reading, and I wish you nothing but the best of luck in your writing journey!

Yours,Rachel

Way way back in the halcyon days of last November, someone on my yearly NaNo thread asked me "where do you start your story?" I love this question for a lot of reasons, but mostly because 1) there are so many different places to start any story, and 2) different starts can create entirely different reading experiences, even if the basic plot is the same.

One of the first things I think about when I sit down to actually plot a book is where I'm going to start. As a general rule, the best place to start your story is always wherever things get interesting, BUT (and here's where it gets cool), "where things get interesting" can vary enormously depending on your audience/genre.

Take this plot I just made up:

When she was nine, Mary's family was eaten in a dragon raid. Swearing revenge, she tracks down a knight of the Sacred Order of Dragon Hunters and demands to join. After saying no many times, the knight eventually gives in and agrees to train her. Many years later, Mary has become an amazing Dragon Hunter and is ready to avenge her parents. But when she finally enters the cave of the dragon who took her family so long ago, she discovers everything she thought she knew is wrong, and the real monsters are the ones she never suspected.

Exciting stuff! Now, where would you start this story? There are a lot of good, exciting spots, many of which could work, but which spot is best depends entirely on what kind of story you want to tell.

For example, if I wanted to write a YA, I'd start when the wounded and determined child Mary approaches the knight and demands he teach her to hunt dragons, and then show how she never gives up even when he says no. Once he eventually gives in, I'd show her training and have her finally get to the dragon cave for the mid-book climax, where I'd turn everything on it's head.

On the other hand, if I wanted to write a gritty, dark fantasy about a woman on a path of bloody revenge, I would jump way ahead and start when Mary is already a professional Dragon Hunter doing her final prep for the hunt she's been training her whole life for, only to get in and realize that everything she's assumed up until now is wrong, and things are much darker and more dangerous than simple dragon killing.