Rachel Aaron's Blog, page 15

July 3, 2015

Let's Talk Numbers: Wild Speculation on the New KU

I know I'm supposed to be on vacation, but this was too exciting not to talk about!!!

As I mentioned a week ago, Amazon has changed the way it calculates borrows for Kindle Unlimited, their book subscription service. In that post, I was pretty optimistic about the proposed changes, and now that new system is actually live...well...I'm not really sure what to think. It could be absolutely amazing, or it could be the death knell for my (and probably a lot of other authors) participation in the program.

For readers, of course, the program looks exactly the same, but for authors with books in Kindle Unlimited, we will now be payed per page read rather than just getting a single payout every time a KU user borrows our book and reads past the 10% mark. Of course, this leads to the question of how much Amazon will pay us per page, and what counts as a page anyway?

These two questions go hand in hand. Of course, due to the vagaries of Kindle Select Global Fund payment system, we won't know how much per page Amazon is going to shell out until they actually pay. That said, many authors are speculating that the KU payout will most likely be around $0.005 per page.

They arrived at this amount using the numbers presented in this email which Amazon sent out to all its KU participating authors last month. Here, Amazon reported that "KU and KOLL customers read nearly 1.9 billion Kindle Edition Normalized Pages (KENPs) of KDP Select books" and that, due to this high volume, the Global Fund for July and August would be set to $11 million. By working backwards, we see that $11 million divided by 1.9 billion pages read works out to about $0.0057 paid out per page that KU readers read.

Half a cent sounds pretty pathetic, and it would be if Amazon was using the print page count, which is the one we're all used to. But hey, this is Amazon we're talking about! And as always with the 'Zon, the reality of the situation is much, much weirder.

Page count in books can vary enormously depending on spacing, how much dialog there is, if there are pictures, etc. To counter this, Amazon had to come up with some way to normalize what counts as a "page" across all their titles, a process they refer to as the Kindle Edition Normalized Page Count (KENPC).

(If you have a title in KU, you can find your book's KENPC by going to your bookshelf in KDP and clicking on the "Promote and Advertise" button. Your KENPC will be listed on the left hand side of the page inside the "Earn royalties from the KDP Select Global Fund" box.)

Now, the very first thing everyone notices about their KENPC is how freaking huge it is. For example, Nice Dragons Finish Last , which has a print page count of 287,has a KENPC of 785 pages. 785!! That's Robert Jordan level!

How did Amazon arrive at this giant number? Again, no one knows for sure, but my favorite theory (as first postulated by author W.R. Pursche here) is that the KENPC for a title is derived by taking a kindle file's total number of characters with spaces and diving by 1000. This math certainly comes up pretty close when I apply it to my own titles, and it just makes a lot of sense. Characters and spaces are the lowest level breakdown of any text display, and I'm willing to bet whatever Amazon picked as their "average Kindle screen" can display 1000 characters + spaces at a time, thus constituting one page.

Now, of course, the truth is probably a lot more complicated, but it doesn't actually matter. What matters here for authors is that, however they derived it, the KENPC page count Amazon is assigning to books is much higher than traditional page counts, which is a pretty freaking sweet deal when you consider they're now paying by page.

For example, under the old system, I got approximately $1.33 every time a KU reader borrowed one of my books and read to at least the 10% mark. Under this new system, though, if a KU reader borrows Nice Dragons Finish Last and reads all the way to the end, and I get paid $0.0057 per every one of those 785 "pages" as estimated by the KENPC, that borrow will end up earning me $0.0057 x 785, or $4.47.

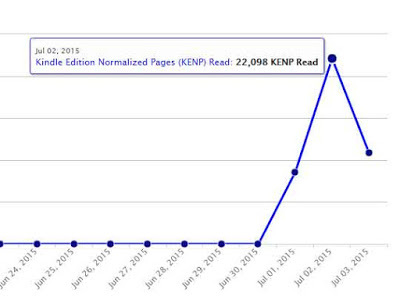

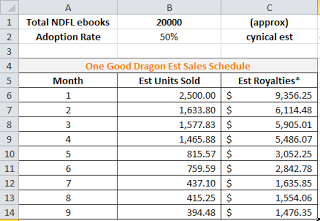

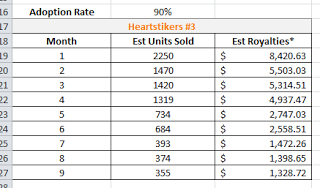

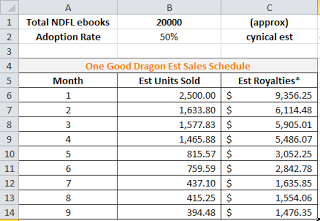

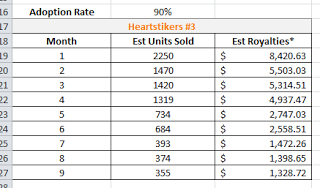

This is almost a dollar more than I would earn from a sale, which is ridiculously awesome when you consider the KU reader is getting my book for "free." This set up is especially awesome for me since I write pretty long books that people tend to read all the way through. Also, since Amazon is now counting every page instead of borrow count, the numbers are freaking crazy. Just look at these graphs!

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

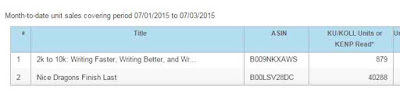

Everyone's saying Monday's reporting was low, but as you see, KU readers clicked through 22 thousand pages of Nice Dragons on Tuesday. and they've gone through nearly 10 thousand pages already this morning. Total this month, a few hours over 2 days in, I've already had over 40k pages read. If the $0.0057 payout is correct, that's $229.64 earned so far, which is already way more than I earned under the old system.

I fully admit these numbers are probably temporarily inflated by my participating in the Kindle Big Deal last month, but even if I go back to my old KU borrow rates of about 10 copies a day, I'm still going to make substantially more money because, under this new system, I'm going from $1.30 a borrow to $4.47 assuming they finish the book. Even if they don't finish, so long as they read more than 233 pages as counted by KENPC, which is about 30%, I'm still making more than the old $1.30 per borrow.

That is a very low bar for success. I'm not saying this change is great for everyone. Like I pointed out in my previous KU post, if you're a short story writer, these changes are less than ideal. But, if the math above is anywhere close to correct, then novel writers (or anyone with a lot of words in KU) stand to make a lot of money under this new system. In fact, these changes could be so good, they might change my mind about leaving KU when my KDP Select contract is up in August.

Once again, though, it all comes down to Amazon. They could still epically screw us all over by paying a tenth of a cent per page, but I don't think that's going to happen. No one wants KU to succeed more than Amazon. That's impossible if there are no good books in the program, and the best way to get and keep good titles is to pay authors well. That's how Amazon got all of us to go indie in the first place, and I'm betting that's what they're doing now with this new KU system.

The only real worry I have left is what this new system will do to sales rank since, under the old system, borrows counted as sales. Will this change now that we're counting pages? I have zero idea, but I'm very interested to see what will happen. (And if you have any good guesses about this, please leave them in the comments below. I'm dying of curiosity!)

Call me an Amazon fangirl if you must, but I'm really excited about these numbers and I can't wait to see the final results when July's actual final payout is announced next month. And you can bet there'll be a blogpost for that, too!

Thank you for reading my wild speculation! I hope you enjoyed it, and as always, happy writing!

Yours,

Rachel

As I mentioned a week ago, Amazon has changed the way it calculates borrows for Kindle Unlimited, their book subscription service. In that post, I was pretty optimistic about the proposed changes, and now that new system is actually live...well...I'm not really sure what to think. It could be absolutely amazing, or it could be the death knell for my (and probably a lot of other authors) participation in the program.

For readers, of course, the program looks exactly the same, but for authors with books in Kindle Unlimited, we will now be payed per page read rather than just getting a single payout every time a KU user borrows our book and reads past the 10% mark. Of course, this leads to the question of how much Amazon will pay us per page, and what counts as a page anyway?

These two questions go hand in hand. Of course, due to the vagaries of Kindle Select Global Fund payment system, we won't know how much per page Amazon is going to shell out until they actually pay. That said, many authors are speculating that the KU payout will most likely be around $0.005 per page.

They arrived at this amount using the numbers presented in this email which Amazon sent out to all its KU participating authors last month. Here, Amazon reported that "KU and KOLL customers read nearly 1.9 billion Kindle Edition Normalized Pages (KENPs) of KDP Select books" and that, due to this high volume, the Global Fund for July and August would be set to $11 million. By working backwards, we see that $11 million divided by 1.9 billion pages read works out to about $0.0057 paid out per page that KU readers read.

Half a cent sounds pretty pathetic, and it would be if Amazon was using the print page count, which is the one we're all used to. But hey, this is Amazon we're talking about! And as always with the 'Zon, the reality of the situation is much, much weirder.

Page count in books can vary enormously depending on spacing, how much dialog there is, if there are pictures, etc. To counter this, Amazon had to come up with some way to normalize what counts as a "page" across all their titles, a process they refer to as the Kindle Edition Normalized Page Count (KENPC).

(If you have a title in KU, you can find your book's KENPC by going to your bookshelf in KDP and clicking on the "Promote and Advertise" button. Your KENPC will be listed on the left hand side of the page inside the "Earn royalties from the KDP Select Global Fund" box.)

Now, the very first thing everyone notices about their KENPC is how freaking huge it is. For example, Nice Dragons Finish Last , which has a print page count of 287,has a KENPC of 785 pages. 785!! That's Robert Jordan level!

How did Amazon arrive at this giant number? Again, no one knows for sure, but my favorite theory (as first postulated by author W.R. Pursche here) is that the KENPC for a title is derived by taking a kindle file's total number of characters with spaces and diving by 1000. This math certainly comes up pretty close when I apply it to my own titles, and it just makes a lot of sense. Characters and spaces are the lowest level breakdown of any text display, and I'm willing to bet whatever Amazon picked as their "average Kindle screen" can display 1000 characters + spaces at a time, thus constituting one page.

Now, of course, the truth is probably a lot more complicated, but it doesn't actually matter. What matters here for authors is that, however they derived it, the KENPC page count Amazon is assigning to books is much higher than traditional page counts, which is a pretty freaking sweet deal when you consider they're now paying by page.

For example, under the old system, I got approximately $1.33 every time a KU reader borrowed one of my books and read to at least the 10% mark. Under this new system, though, if a KU reader borrows Nice Dragons Finish Last and reads all the way to the end, and I get paid $0.0057 per every one of those 785 "pages" as estimated by the KENPC, that borrow will end up earning me $0.0057 x 785, or $4.47.

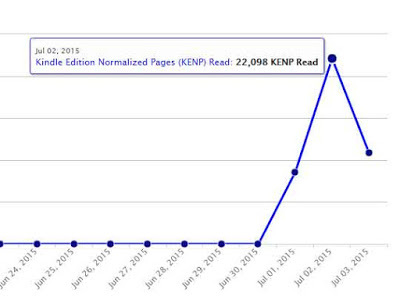

This is almost a dollar more than I would earn from a sale, which is ridiculously awesome when you consider the KU reader is getting my book for "free." This set up is especially awesome for me since I write pretty long books that people tend to read all the way through. Also, since Amazon is now counting every page instead of borrow count, the numbers are freaking crazy. Just look at these graphs!

Click to enlarge.

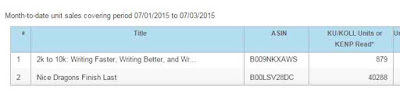

Click to enlarge.Everyone's saying Monday's reporting was low, but as you see, KU readers clicked through 22 thousand pages of Nice Dragons on Tuesday. and they've gone through nearly 10 thousand pages already this morning. Total this month, a few hours over 2 days in, I've already had over 40k pages read. If the $0.0057 payout is correct, that's $229.64 earned so far, which is already way more than I earned under the old system.

I fully admit these numbers are probably temporarily inflated by my participating in the Kindle Big Deal last month, but even if I go back to my old KU borrow rates of about 10 copies a day, I'm still going to make substantially more money because, under this new system, I'm going from $1.30 a borrow to $4.47 assuming they finish the book. Even if they don't finish, so long as they read more than 233 pages as counted by KENPC, which is about 30%, I'm still making more than the old $1.30 per borrow.

That is a very low bar for success. I'm not saying this change is great for everyone. Like I pointed out in my previous KU post, if you're a short story writer, these changes are less than ideal. But, if the math above is anywhere close to correct, then novel writers (or anyone with a lot of words in KU) stand to make a lot of money under this new system. In fact, these changes could be so good, they might change my mind about leaving KU when my KDP Select contract is up in August.

Once again, though, it all comes down to Amazon. They could still epically screw us all over by paying a tenth of a cent per page, but I don't think that's going to happen. No one wants KU to succeed more than Amazon. That's impossible if there are no good books in the program, and the best way to get and keep good titles is to pay authors well. That's how Amazon got all of us to go indie in the first place, and I'm betting that's what they're doing now with this new KU system.

The only real worry I have left is what this new system will do to sales rank since, under the old system, borrows counted as sales. Will this change now that we're counting pages? I have zero idea, but I'm very interested to see what will happen. (And if you have any good guesses about this, please leave them in the comments below. I'm dying of curiosity!)

Call me an Amazon fangirl if you must, but I'm really excited about these numbers and I can't wait to see the final results when July's actual final payout is announced next month. And you can bet there'll be a blogpost for that, too!

Thank you for reading my wild speculation! I hope you enjoyed it, and as always, happy writing!

Yours,

Rachel

Published on July 03, 2015 06:34

July 1, 2015

Writing Wednesdays: How to Deal With a Character Taking Over Your Book

We're on a bit of a sudden enforced vacation here at Casa de Aaron Bach. We didn't realize summer camp was closed the entire week of July 4, so it's suddenly "madly run around North Georgia doing outdoorsy stuff with our son!" time. Because of the interruptions, today's Writing Wednesday is going to be a little different.

Every November for the last four years, I've done an AMA with writers over at the NaNoWriMo fantasy forums. These posts are super fun and one of the highlights of my year. The question format gives me a chance to write out a lot of my writing processes and strategies, some of which I didn't even think about until someone asked me. The result is a ton of information that I'm very proud of, but, due to the inherent nature of forum replies, can be pretty hard to read.

So today, in the spirit of posting something interesting while also not abandoning my husband for too long to the whims of a bored 5-year-old (THANKS TRAVIS!), here's one of my favorite question/answer pairs from the thread, conveniently extracted and cleaned up for your reading pleasure.

I promise we'll be back to the new stuff next Wednesday. For now, though, let's talk character wrangling!

Writing Wednesdays: How to Deal With a Character Taking Over Your Book

Emma Rowene asks:

My main character shares some of Eli's personality traits, I think. He's charming, skilled, facetious...but I'm finding that I'm having some trouble pulling it off. He's sort of overshadowing the other characters (who I think are also pretty great) and is coming across as not as deep a character as he should be because of some of these personality traits. So I guess my question is: do you have any advice? How did you go about writing Eli?

Rachel Aaron:

I had the exact same problem when I was writing Eli! When you've got one character with a super strong personality, especially he's a voice you love and find really fun to write, it's all too easy to end up with that character dominating every scene he's in. And while that's not technically bad (assuming he's your main character), it can make your book very one note by stealing everyone else's page time.

Personally, I solved this problem by increasing Eli's character flaws. Eli's cockiness, checkered past, and inability to keep his mouth shut got him into a lot of trouble, which gave the other characters a chance to shine by saving his butt/yelling at him/coming up with their own plans. 2) I made sure that all my other major characters had interesting and important story lines of their own (Nico and her demon, Josef and his sword, Miranda and her spirits, etc). So long as your people have goals they're actively pursuing and which are complicating the plot away from your MC, it's much easier for them to make their voices heard. And finally, 3) I made sure to shift the POV away from Eli for large sections of the text. This allowed me to tell other parts of the story Eli and Co. couldn't know about as well as giving me opportunities to show the action from alternate, non-Eli points of view, even if Eli himself was in the scene.

This final division paid off two fold. First, because watching from another character's POV was often actually more interesting than being in Eli's head since they didn't know what Eli was going to do. And second, because it gave me lots of chances to develop the POV characters independently while still telling Eli's story. I used this trick especially to develop characters who wouldn't otherwise talk a lot, but had very definite opinions, like Josef (stoic swordsman) and Nico (quiet, introverted demonseed).

Now, this was just how I solved my "Eli keeps taking up all the air" conundrum. I'm sure there are infinite other ways to do this exact same thing (that's the great thing about writing, there's always more than one way to fix a problem!). Still, I hope they'll give you a kicking off point to try and fix the same issue in your book.

That said, I do want to address the concern you bring up about shallowness. When you're writing a charming, skilled, charismatic character, making sure your reader doesn't think they're shallow is a huge issue. We tend to think these people are shallow IRL, so you're already writing up hill when you pick this kind of personality as your main character. The trick is to make sure your character has serious problems and showcasing those in way that makes an otherwise overpowered, charismatic character seem deeply sympathetic. Eli might have been charming, handsome, and seemingly care free, but it was clear by the middle of book one that his take-nothing-seriously attitude was just a cover up for some extremely deep and messed up issues.

Readers love this stuff. They love getting to feel like they're on the inside of a character no one else really knows. So don't be afraid to reveal your character's demons early and often, especially if that character might come across as Too Good To Be True otherwise. If you can pull that off properly, you'll end up with a charming but wounded character people will love and root for instead of just another smug bastard.

I really hope that helps! Sorry to go on so long. As you see, you asked me a question very near and dear to my heart. I hope my experience helps make your writing easier, and best of luck on your book! It sounds awesome to me, but then, I might have a very soft spot for charming rogues.

I hope you enjoyed this blast from November Past! I'll be doing NaNo again this year, so I hope you'll drop by and ask a question! If this post wasn't enough to whet your writing whistle, click here (or in the "Writing" label below) to see 7 years worth of Rachel writing posts! (No promises about the ones at the beginning, though. ;) )

Thank you as always for reading, and happy writing!

Yours,

Rachel

Every November for the last four years, I've done an AMA with writers over at the NaNoWriMo fantasy forums. These posts are super fun and one of the highlights of my year. The question format gives me a chance to write out a lot of my writing processes and strategies, some of which I didn't even think about until someone asked me. The result is a ton of information that I'm very proud of, but, due to the inherent nature of forum replies, can be pretty hard to read.

So today, in the spirit of posting something interesting while also not abandoning my husband for too long to the whims of a bored 5-year-old (THANKS TRAVIS!), here's one of my favorite question/answer pairs from the thread, conveniently extracted and cleaned up for your reading pleasure.

I promise we'll be back to the new stuff next Wednesday. For now, though, let's talk character wrangling!

Writing Wednesdays: How to Deal With a Character Taking Over Your Book

Emma Rowene asks:

My main character shares some of Eli's personality traits, I think. He's charming, skilled, facetious...but I'm finding that I'm having some trouble pulling it off. He's sort of overshadowing the other characters (who I think are also pretty great) and is coming across as not as deep a character as he should be because of some of these personality traits. So I guess my question is: do you have any advice? How did you go about writing Eli?

Rachel Aaron:

I had the exact same problem when I was writing Eli! When you've got one character with a super strong personality, especially he's a voice you love and find really fun to write, it's all too easy to end up with that character dominating every scene he's in. And while that's not technically bad (assuming he's your main character), it can make your book very one note by stealing everyone else's page time.

Personally, I solved this problem by increasing Eli's character flaws. Eli's cockiness, checkered past, and inability to keep his mouth shut got him into a lot of trouble, which gave the other characters a chance to shine by saving his butt/yelling at him/coming up with their own plans. 2) I made sure that all my other major characters had interesting and important story lines of their own (Nico and her demon, Josef and his sword, Miranda and her spirits, etc). So long as your people have goals they're actively pursuing and which are complicating the plot away from your MC, it's much easier for them to make their voices heard. And finally, 3) I made sure to shift the POV away from Eli for large sections of the text. This allowed me to tell other parts of the story Eli and Co. couldn't know about as well as giving me opportunities to show the action from alternate, non-Eli points of view, even if Eli himself was in the scene.

This final division paid off two fold. First, because watching from another character's POV was often actually more interesting than being in Eli's head since they didn't know what Eli was going to do. And second, because it gave me lots of chances to develop the POV characters independently while still telling Eli's story. I used this trick especially to develop characters who wouldn't otherwise talk a lot, but had very definite opinions, like Josef (stoic swordsman) and Nico (quiet, introverted demonseed).

Now, this was just how I solved my "Eli keeps taking up all the air" conundrum. I'm sure there are infinite other ways to do this exact same thing (that's the great thing about writing, there's always more than one way to fix a problem!). Still, I hope they'll give you a kicking off point to try and fix the same issue in your book.

That said, I do want to address the concern you bring up about shallowness. When you're writing a charming, skilled, charismatic character, making sure your reader doesn't think they're shallow is a huge issue. We tend to think these people are shallow IRL, so you're already writing up hill when you pick this kind of personality as your main character. The trick is to make sure your character has serious problems and showcasing those in way that makes an otherwise overpowered, charismatic character seem deeply sympathetic. Eli might have been charming, handsome, and seemingly care free, but it was clear by the middle of book one that his take-nothing-seriously attitude was just a cover up for some extremely deep and messed up issues.

Readers love this stuff. They love getting to feel like they're on the inside of a character no one else really knows. So don't be afraid to reveal your character's demons early and often, especially if that character might come across as Too Good To Be True otherwise. If you can pull that off properly, you'll end up with a charming but wounded character people will love and root for instead of just another smug bastard.

I really hope that helps! Sorry to go on so long. As you see, you asked me a question very near and dear to my heart. I hope my experience helps make your writing easier, and best of luck on your book! It sounds awesome to me, but then, I might have a very soft spot for charming rogues.

I hope you enjoyed this blast from November Past! I'll be doing NaNo again this year, so I hope you'll drop by and ask a question! If this post wasn't enough to whet your writing whistle, click here (or in the "Writing" label below) to see 7 years worth of Rachel writing posts! (No promises about the ones at the beginning, though. ;) )

Thank you as always for reading, and happy writing!

Yours,

Rachel

Published on July 01, 2015 06:48

June 24, 2015

Writing Wednesdays: What Description Really Does

Nice Dragons Finish Last is $0.99 for only one more week! Get you one!

Writing Wednesdays: What Description Really Does

Like exposition, writing description is one of those things that, if you're not already inclined to it, can feel like an anchor around your paragraphs. It's all too easy to go overboard describing what your characters see and feel, and while you may think you're giving your readers what they need, you're really just sinking your book under dead weight. If you go too light on description, though, your readers don't know what anything looks or smells or feels like and the book falls flat.

Just like everything else in writing, good description comes down to good execution, which is just a fancy way of saying "You've got to do it well." That's no sweat if you're one of those writers who already loves description. For me, though, description is one of those writing elements I've always struggled with. I'm a plot and characters girl who'd do everything in dialogue if she could. I'm also not a very visual person, which means I'm constantly forgetting to describe basic things like what characters are wearing because I just don't think about it. My readers do, though, and boy did they let me know.

So right from the beginning, I knew I had a problem with descriptions, and like any good writer, I got to work on fixing that.

Most problems in writing can be solved through experience and listening to feedback. If you've got someone you trust to read your work and give it to you straight--and then you actually listen to the criticism and make changes as appropriate--you can solve almost any writing issue pretty quickly. But this cycle of constructive criticism and growth gets hamstrung when the problem in question involves something that you don't actually care about as a reader, like me and descriptions. I didn't notice them when I read books, so I didn't really think critically about putting them into my own.

I think every author has a blind spot like this somewhere. Unfortunately, many of us use this as an excuse to take the Mind Over Matter approach, as in "If I don't mind, it doesn't matter." The book seems awesome to me! Why should I care if people are complaining about something I see as unimportant?

I don't think I have to explain why this is a toxic and self destructive way to think. Even if something doesn't matter to us, we're not our audience. Writing for publication means thinking about appealing to a wide spectrum of readers, not just the ones who think like me. If I want to reach that broad audience, I have to try to be good (or at least not bad) on all levels, not just the ones I care about. I'm not saying authors should freak out over every negative comment--that way lies madness--but if readers are consistently complaining about something, then it's a real problem, and it's up to us as good authors to fix it.

So how did I fix my description problem? Did I keep the criticisms in mind and focus on consciously adding more and better description to my work? Well, yes, but that was only the first step, something to help me treat the symptoms. I'm a firm believer that really good writing should be fun and flow naturally, and constantly harping on myself to remember my descriptions was definitely not part of that.

If I wanted to keep my natural, fun writing rhythm, then writing good descriptions needed to become part of my creative process, not something I tacked on after the fact. To do that, I needed to look past my own antipathy and figure out what good description actually does in a novel. It's like that one tool in Photoshop you never use because you don't actually understand how it works. Once you figure it out, though, you don't know how you ever lived without it. That was the awakening I was going for, and sure enough, once I took the time to actually stop and ask "what does description actually do?" I started caring about it a whole lot more.

Cool backstory, Rachel, but can we actually talk about description now?

Right! Moving on!

On the surface, description just seems like writing finishing work. It's not part of the structure, like characters and plot, it's just language that tells your reader how to imagine the things and people in your book, like costume and set design for a movie. But right there, in that seemingly dismissive comparison, we see how important description is, because there have been any number of movies that have used costume and set design to enormous effect, telling huge swaths of the story with visuals alone before any dialogue had even been spoken.

A perfect example of this is my current darling: Mad Max Fury Road.

There are probably 15 minutes of dialogue total in the entire film. The vast majority of the narrative--the exposition, the stakes, the world building, the characters' struggles and histories--is told entirely through what, in a book, would be description. It is the very definition of show, don't tell, which is exactly what good description exists to do. It's not just labeling your character's eye color or explaining what a sword looks like. Used properly, description becomes an entire other vehicle for the story that runs in silent parallel to the action and the dialogue.

Writing good description is all about balancing two needs: information and tension. You need to make sure your reader has a good a mental picture of what your world looks like, especially if you plan to use that information to great effect later. At the same time, though, if you pause the story for a 1000 word description of architecture, no matter how relevant, any tension you built before that point will be murdered.

Since boredom is my sworn enemy, I've historically erred on the side of too little, but (as was evident from my grumpy readers) that was almost as bad as too much. What I really should have been focusing on (and eventually learned to love) was using description as a tool. Like any good tool, you only need to pull it out when you've got a specific job to do.

Way back when I was writing my very fist book (the one that I never sold), I thought that if a character saw something, I had to describe it. This led to a lot of boring "here's what the trees look like" paragraphs that agents described as "dragging" in their rejection letters. The lesson I took from this was don't describe anything unless you have to, but that was wrong, too. The key I was missing was balance. You have to describe things so the reader knows what your world looks/feels like, but which things you need to describe is completely dependent on how important they are to your story.

For example, if a character walks into a room, you don't need to describe every aspect of the room (like Bad Writer Rachel used to). You just need to describe enough to convey the feelings and information you want your reader to pick up in this part of the story. If my character is waiting to meet with the Emperor of a failing empire, but I didn't want to actually sit there and info dump about how the empire is failing, I'd shift all that exposition to the description. By filling the waiting room with faded banners, shelves that weren't dusted, and displays of treasures from conquered peoples that my POV character now though of as being in extremely bad taste, I could passively tell the entire story of a ruling civilization's decline without actually saying a word.

This is ideal of description as story, but sometimes you need descriptions for more practical reasons. Describing how many chairs are in a room and how they're positioned might sound boring beyond belief, but if your MC is going to be using them as weapons later, you can't escape it. If your reader doesn't know what those chairs look like and where they're located beforehand, it's going to look like your MC is just throwing chairs out of nowhere à la Bad Cop from The Lego Movie.

These sort of practical "this goes here" descriptions were the ones I struggled with the most. I had to describe certain things for technical reasons--like the giant cathedral window I was going to throw someone out of--but stopping the action to actually write all of that out completely broke the tension. If I didn't describe the setting beforehand, though, it looked like I made up a window on the spot just to throw someone out of it, which is one of the hallmarks of bad writing.

Fortunately for me, the solution to this problem turned out to be stupidly simple. After a lot of trial and error, I discovered that the secret to writing technical "where/what stuff is" descriptions without ruining the rest of the scene was to do the vast majority of my description while I was doing something else.

Take the sentence below:

Bob and Julius burst into the abandoned classroom, knocking the dusty chairs and desks out of their way as they ran for the window.

This sentence is 100% description, but it's disguised as an action sentence. The reader's interest is held because we have two characters running through a room, ostensibly from or toward something. All that movement and implied threat creates tension and interest for the reader. They want to know where the characters are going, and if they're going to make it. At the same time, though, I'm also telling them what the room looks like (dusty, abandoned, in a school, probably dark) and what's in it (chairs, desks, and other things you'd find in a classroom).

I could have done all of this by stopping the action to describe the room in detail, but that would have put a speed bump in the middle of my scene, and F that. Any time you stop the action to say what something looks like, you break the flow, and while that can be a powerful narrative tool, especially if you have something really dramatic/shocking/important to describe, most of the time it's bad bad bad. You don't ever want to break the reader out of the scene unless you're doing it on purpose for shock value, like so:

She turned the corner and froze, eyes wide. In front of her was...(insert paragraph of description here).

As you see, that sort of "stop the camera and let it sink in" reveal can only be done so many times, and only for really important things you're certain the reader's going to be interested in. Most of the time, though, I've found my best bet is to try and sneak descriptions in wherever I can. It's just like when I talked about Info Filling vs Info Dumping for exposition. Rather than dumping my descriptions all at once, I break everything up and sprinkle it around wherever it'll fit.

For example, if a scene has two characters standing and talking, I'll move them around and let them interact with the environment--picking up knickknacks, brushing dust off counter tops, smelling the dry scent of old books, tightening their cloaks against the damp, etc. This kind of sneaky, between-the-lines description lets me weave in tons of setting exposition while also doing dialogue. Plus, if I'm really on the ball, I can also use the character's fidgeting to show how they're feeling, like having them grip something too tightly. By using our description strategically, we're hitting a whole flock of birds with one stone here, and that is always awesome.

Dialogue isn't the only place you can use this trick, either. Letting your characters interact with the environment creates a never ending source of passive exposition. Trip them on rocks, get them stuck in mud, drench them with rain, fill the air with the sour smells of the market, make their formal clothing too tight, you get the idea. It's all about balancing information with tension. Doing whatever it takes to set the scene without actually having to stop and set the scene.

And that's how I do description! These strategies have helped me come a long way with my descriptions since my first book, and I now count good description as one of the most powerful weapons on my writing utility belt. Whether you struggle with description or not, though, it's always good to understand how an aspect of writing actually functions mechanically within a story. Knowledge is power!

Thank you as always for reading, and if you want more technical writing tips/tricks/discussions, check out the Writing Wednesday archives!

Until next time, I remain your friendly neighborhood Spiderman author,

Rachel

Writing Wednesdays: What Description Really Does

Like exposition, writing description is one of those things that, if you're not already inclined to it, can feel like an anchor around your paragraphs. It's all too easy to go overboard describing what your characters see and feel, and while you may think you're giving your readers what they need, you're really just sinking your book under dead weight. If you go too light on description, though, your readers don't know what anything looks or smells or feels like and the book falls flat.

Just like everything else in writing, good description comes down to good execution, which is just a fancy way of saying "You've got to do it well." That's no sweat if you're one of those writers who already loves description. For me, though, description is one of those writing elements I've always struggled with. I'm a plot and characters girl who'd do everything in dialogue if she could. I'm also not a very visual person, which means I'm constantly forgetting to describe basic things like what characters are wearing because I just don't think about it. My readers do, though, and boy did they let me know.

So right from the beginning, I knew I had a problem with descriptions, and like any good writer, I got to work on fixing that.

Most problems in writing can be solved through experience and listening to feedback. If you've got someone you trust to read your work and give it to you straight--and then you actually listen to the criticism and make changes as appropriate--you can solve almost any writing issue pretty quickly. But this cycle of constructive criticism and growth gets hamstrung when the problem in question involves something that you don't actually care about as a reader, like me and descriptions. I didn't notice them when I read books, so I didn't really think critically about putting them into my own.

I think every author has a blind spot like this somewhere. Unfortunately, many of us use this as an excuse to take the Mind Over Matter approach, as in "If I don't mind, it doesn't matter." The book seems awesome to me! Why should I care if people are complaining about something I see as unimportant?

I don't think I have to explain why this is a toxic and self destructive way to think. Even if something doesn't matter to us, we're not our audience. Writing for publication means thinking about appealing to a wide spectrum of readers, not just the ones who think like me. If I want to reach that broad audience, I have to try to be good (or at least not bad) on all levels, not just the ones I care about. I'm not saying authors should freak out over every negative comment--that way lies madness--but if readers are consistently complaining about something, then it's a real problem, and it's up to us as good authors to fix it.

So how did I fix my description problem? Did I keep the criticisms in mind and focus on consciously adding more and better description to my work? Well, yes, but that was only the first step, something to help me treat the symptoms. I'm a firm believer that really good writing should be fun and flow naturally, and constantly harping on myself to remember my descriptions was definitely not part of that.

If I wanted to keep my natural, fun writing rhythm, then writing good descriptions needed to become part of my creative process, not something I tacked on after the fact. To do that, I needed to look past my own antipathy and figure out what good description actually does in a novel. It's like that one tool in Photoshop you never use because you don't actually understand how it works. Once you figure it out, though, you don't know how you ever lived without it. That was the awakening I was going for, and sure enough, once I took the time to actually stop and ask "what does description actually do?" I started caring about it a whole lot more.

Cool backstory, Rachel, but can we actually talk about description now?

Right! Moving on!

On the surface, description just seems like writing finishing work. It's not part of the structure, like characters and plot, it's just language that tells your reader how to imagine the things and people in your book, like costume and set design for a movie. But right there, in that seemingly dismissive comparison, we see how important description is, because there have been any number of movies that have used costume and set design to enormous effect, telling huge swaths of the story with visuals alone before any dialogue had even been spoken.

A perfect example of this is my current darling: Mad Max Fury Road.

There are probably 15 minutes of dialogue total in the entire film. The vast majority of the narrative--the exposition, the stakes, the world building, the characters' struggles and histories--is told entirely through what, in a book, would be description. It is the very definition of show, don't tell, which is exactly what good description exists to do. It's not just labeling your character's eye color or explaining what a sword looks like. Used properly, description becomes an entire other vehicle for the story that runs in silent parallel to the action and the dialogue.

Writing good description is all about balancing two needs: information and tension. You need to make sure your reader has a good a mental picture of what your world looks like, especially if you plan to use that information to great effect later. At the same time, though, if you pause the story for a 1000 word description of architecture, no matter how relevant, any tension you built before that point will be murdered.

Since boredom is my sworn enemy, I've historically erred on the side of too little, but (as was evident from my grumpy readers) that was almost as bad as too much. What I really should have been focusing on (and eventually learned to love) was using description as a tool. Like any good tool, you only need to pull it out when you've got a specific job to do.

Way back when I was writing my very fist book (the one that I never sold), I thought that if a character saw something, I had to describe it. This led to a lot of boring "here's what the trees look like" paragraphs that agents described as "dragging" in their rejection letters. The lesson I took from this was don't describe anything unless you have to, but that was wrong, too. The key I was missing was balance. You have to describe things so the reader knows what your world looks/feels like, but which things you need to describe is completely dependent on how important they are to your story.

For example, if a character walks into a room, you don't need to describe every aspect of the room (like Bad Writer Rachel used to). You just need to describe enough to convey the feelings and information you want your reader to pick up in this part of the story. If my character is waiting to meet with the Emperor of a failing empire, but I didn't want to actually sit there and info dump about how the empire is failing, I'd shift all that exposition to the description. By filling the waiting room with faded banners, shelves that weren't dusted, and displays of treasures from conquered peoples that my POV character now though of as being in extremely bad taste, I could passively tell the entire story of a ruling civilization's decline without actually saying a word.

This is ideal of description as story, but sometimes you need descriptions for more practical reasons. Describing how many chairs are in a room and how they're positioned might sound boring beyond belief, but if your MC is going to be using them as weapons later, you can't escape it. If your reader doesn't know what those chairs look like and where they're located beforehand, it's going to look like your MC is just throwing chairs out of nowhere à la Bad Cop from The Lego Movie.

These sort of practical "this goes here" descriptions were the ones I struggled with the most. I had to describe certain things for technical reasons--like the giant cathedral window I was going to throw someone out of--but stopping the action to actually write all of that out completely broke the tension. If I didn't describe the setting beforehand, though, it looked like I made up a window on the spot just to throw someone out of it, which is one of the hallmarks of bad writing.

Fortunately for me, the solution to this problem turned out to be stupidly simple. After a lot of trial and error, I discovered that the secret to writing technical "where/what stuff is" descriptions without ruining the rest of the scene was to do the vast majority of my description while I was doing something else.

Take the sentence below:

Bob and Julius burst into the abandoned classroom, knocking the dusty chairs and desks out of their way as they ran for the window.

This sentence is 100% description, but it's disguised as an action sentence. The reader's interest is held because we have two characters running through a room, ostensibly from or toward something. All that movement and implied threat creates tension and interest for the reader. They want to know where the characters are going, and if they're going to make it. At the same time, though, I'm also telling them what the room looks like (dusty, abandoned, in a school, probably dark) and what's in it (chairs, desks, and other things you'd find in a classroom).

I could have done all of this by stopping the action to describe the room in detail, but that would have put a speed bump in the middle of my scene, and F that. Any time you stop the action to say what something looks like, you break the flow, and while that can be a powerful narrative tool, especially if you have something really dramatic/shocking/important to describe, most of the time it's bad bad bad. You don't ever want to break the reader out of the scene unless you're doing it on purpose for shock value, like so:

She turned the corner and froze, eyes wide. In front of her was...(insert paragraph of description here).

As you see, that sort of "stop the camera and let it sink in" reveal can only be done so many times, and only for really important things you're certain the reader's going to be interested in. Most of the time, though, I've found my best bet is to try and sneak descriptions in wherever I can. It's just like when I talked about Info Filling vs Info Dumping for exposition. Rather than dumping my descriptions all at once, I break everything up and sprinkle it around wherever it'll fit.

For example, if a scene has two characters standing and talking, I'll move them around and let them interact with the environment--picking up knickknacks, brushing dust off counter tops, smelling the dry scent of old books, tightening their cloaks against the damp, etc. This kind of sneaky, between-the-lines description lets me weave in tons of setting exposition while also doing dialogue. Plus, if I'm really on the ball, I can also use the character's fidgeting to show how they're feeling, like having them grip something too tightly. By using our description strategically, we're hitting a whole flock of birds with one stone here, and that is always awesome.

Dialogue isn't the only place you can use this trick, either. Letting your characters interact with the environment creates a never ending source of passive exposition. Trip them on rocks, get them stuck in mud, drench them with rain, fill the air with the sour smells of the market, make their formal clothing too tight, you get the idea. It's all about balancing information with tension. Doing whatever it takes to set the scene without actually having to stop and set the scene.

And that's how I do description! These strategies have helped me come a long way with my descriptions since my first book, and I now count good description as one of the most powerful weapons on my writing utility belt. Whether you struggle with description or not, though, it's always good to understand how an aspect of writing actually functions mechanically within a story. Knowledge is power!

Thank you as always for reading, and if you want more technical writing tips/tricks/discussions, check out the Writing Wednesday archives!

Until next time, I remain your friendly neighborhood Spiderman author,

Rachel

Published on June 24, 2015 06:42

June 22, 2015

Kindle Unlimited Is Changing Their Payment Structure and Why I Think That's Awesome

I was on a sort-of vacation last week (well, as close to vacation as I get), so I didn't hear about the newly unveiled Kindle Unlimited payment structure changes until my (not actually publishing related) friend mentioned it to me at dinner.

Since any change to KU is the definition of Relevant to My Interests, I proceeded to be very rude and looked it up right there at the table, and you know what? I really liked what I read, and here's why.

Amazon's imagery was more right than they knew. It's a wild sea out there.

Amazon's imagery was more right than they knew. It's a wild sea out there.

Unlike many authors I talk to who tend to see Amazon'g book subscription service as EEEEVIIIIIIIL, I've been a pretty big fan of KU since Amazon announced it last year. I wrote a post breaking down the math of why KU should make everyone a lot of money back when it was first announced, and my opinion is pretty much the same now as it was then: that the Amazon exclusivity requirement sucks, but overall KU participation should be a good deal for most authors.

I'm pleased to report that my own experience with the program has been largely positive. I've been in KU for a year now, and while it's been much better for my fiction than 2k to 10k, I don't really have complaints on either score. That said, I will be taking my books out of KU later this year to try out other venues (gotta try new things!), but that decision is based entirely on wanting to reach out to new, non-Amazon markets, not because I'm dissatisfied with the program.

BUT (you knew there was a but, right?), as much as I personally love the idea and most of the practice of KU, it's no secret that the payment system was notoriously easy to game. Scamming was ridiculously rampant, and that's the problem this new KU payment system seeks to remedy.

How Kindle Unlimited Worked

Kindle Unlimited pays authors out of a fund set up by Amazon. Think of it as a large pie that Amazon slices up and doles out to its authors based on how many KU subscribers read their books. Previously, your slice of the pie was calculated based on how many KU readers borrowed your book and read to at least the 10% mark. Short story, graphic novel, epic Fantasy tome, doesn't matter. So long as they made it to that 10% mark, you got paid the full borrow amount (usually about $1.33), regardless of how long your book was or whether or not that reader actually finished it.

I'm sure you can already see the problems inherent to this set up. Almost as soon as Amazon posted these rules, the online bookstore was flooded with ten page "novels" written by people like "James Paterson," "Steven King," and "Norah Roberts." These titles were deliberate scams designed to trick KU readers into clicking on what they thought was a new release by a mega bestseller. Under the old KU rules, it didn't even matter if they instantly realized they'd been scammed. With a 10 page book, they only needed to look at one page in order for it to count as the 10% read the scammer needed to get paid the full KU payout.

Since all KU authors are paid out of the same pot, these scams hurt everyone. Not only were scammers sucking money away from legitimate authors, they were infuriating readers and making KU itself look bad. Amazon knew this and ruthlessly cracked down, but it was like fighting a hydra. Strike one scammer down and two more would pop up in their place. So, in order to save Kindle Unlimited (and themselves a ton of policing), Amazon changed the rules.

How Kindle Unlimited Will Work Starting July 1, 2015 (and Why It Rocks)

Starting next month, Kindle Unlimited will now pay out by pages read. Showing that Amazon has learned from their mistakes, this new system works off an algorithm that averages ebook page counts by total wordcount (so you can't just give all your books huge fonts and tons of white space) and starts the reader on the Prologue/Chapter 1 (so you can't just add tons of obviously skip-able front matter to pad your page count). In order to get paid the maximum borrow amount, a book will have to have quality content that captures and holds the reader's attention all the way to the end. (You know, the stuff that should be there anyway.)

Personally, I'm a HUGE fan of this change. I love the idea that Amazon is literally paying KU authors for being good writers instead of just good marketers. Under this system, authors who write good books people want to read are the ones who reap the maximum reward.

I also love that it incentivizes longer books, because I really dislike the current practice of chopping up would would otherwise be a single novel into multiple "serial" segments to maximize revenue. Not that I think any author who did this is evil or a scammer. Business is all about figuring out ways to get the maximum profit from your investment, and there is no arguing that you made a lot more money from borrows and sales off five 20k titles priced at $2.99 each than off one 100k novel priced at $4.99. But while some authors love the idea of serials and wrote them legitimately, KBoards and other self pub hangouts were constantly barraged with authors asking if they should cut up their novels into serial format simply because of the situation I described above, and I think that sucks.

When a system encourages artists to put their work into a format readers hate (and make no mistake, readers HATE serials. Just look at the reviews for any top selling serial and and you'll see what I mean), that's a bad system. It's bad for readers, it's bad for authors, it's bad for the book business in general. You want people to be happy when they finish your story, not pissed because they're having to buy/borrow 5 books to get one novel's worth of story.

I think Amazon became very aware of this, and the new KU borrow system is a step toward addressing it. Now, instead of encouraging authors to put out as many titles as possible, length be damned, Amazon is financially rewarding authors who tell good stories, regardless of format. When it comes to KU at least, the 100k word novel sold as one title will earn exactly the same as the 100k novel divided up into five 20k segments, encouraging novelists to write in the way that best suits the story.

As a writer who firmly believes that a story should be exactly as long or short as it needs to be, and as a reader who loathes arbitrary serial fiction (again, not talking about stories that are actually written to be serial format, but books that have been obviously chopped up just to take advantage of Amazon's payment structure), this is a HUGE change for the better. I am fully behind these new KU changes, and I hope Amazon takes more steps like this in the future.

But Rachel, How Can You Support the New KU Changes When They're Hurting Short Story Writers?!

When you look at the complaints leveled against the new KU, almost all of them come from two camps: short story writers, and authors who feel they should be paid for any amount of reading, regardless of whether or not the reader finishes the book.

Of these two groups, my heart goes out of the short story writers the most. Short stories are a very demanding form of fiction, and I fully respect the work that goes into them. That said, I don't think Amazon's new system is unfair, because no matter how much you put into your short fiction, it's still short. A short story might be deeper than the abyssal trench and more beautiful than a rainbow at sunrise, but the fact remains that it still takes less time to read and produce than a novel-length work of comparable quality.

In that light, I feel that the new system is actually more fair to authors since it rewards novelists and short story writers equally for their efforts rather than paying the same for 1,000 words as for 100,000 as was the case before. It's also more in line with the rest of the industry that has always paid by the word for short fiction. Plus, you can still charge whatever you want for people to buy your story, so it's not like Amazon's taking away your ability to make money off your short fiction. I do sympathize with the fact that you can no longer make $1.33 off a borrow on a $0.99 short story, but we all knew that gravy train had to dry up sometime ;).

But while I admit this new system is less advantageous to short fiction, I still think it's a good change over all. Fewer scammers gumming up the KU library improves the discoverability of quality books, and that means more borrows and more money for everyone!

As for the second group, the ones who feel they should get a full borrow price for any reading regardless of whether the reader finishes or not...you're entitled to that opinion. I don't agree, of course, but I'm not going to tell you how to feel. Personally, though, I think that if the KU part of your business model depends on getting your money up front because you're not confident readers are going to read your book all the way to the end, you have a much bigger problem than how KU borrows are calculated.

Wow, That's a Lot of Praise. So Are You 100% Behind the New KU?

Well, about that. I've always thought KU was a pretty good program, and these new changes make it even better. But while Amazon has addressed some of the problems with the KU model, they haven't touched what I see as the two greatest problem with the program: the Amazon exclusivity requirement, and fact that payments are still made out of the KDP Select Global Fund.

Where Things Get Less Awesome

While I love love LOVE the idea that KU has abandoned as single payout at 10% in favor of paying a small bounty per page read, just how much this per-page payment will be is impossible to say since Kindle Unlimited pays authors out of a fund that changes every month.

Let me be blunt: I REALLY f-ing hate this system. If you need a refresher for why it sucks, here is how Amazon explains the rules.

When you earn your living off your books, that is some vitally important math. I know it seems weird after spending this entire post singing the new KU's praises, but this complete lack of reliable numbers and the odious Amazon exclusivity requirement is why I've decided take my books out of KU when the agreement expires later this year, and why One Good Dragon Deserves Another will not be included in the program at all in the foreseeable future.

Again, it's not because I haven't been making money--I've made lovely money off KU over the last year--it's just because that money isn't enough to outweigh the cost of not making my book available in every other market. And that's really kind of a shame, because my novels are exactly the kind of books that would do the best under the new KU system.

So Is the New KU Worth It?

That depends on you.

When I first signed up for KU, I was seeing one sale of my self-published titles on other vendors for every one hundred I was getting from Amazon. By that math, KU was totally worth it for me. Even at an insanely low $1 per borrow (a worst-case scenario that KU has never actually hit), I only needed about 10 borrows a day to make up all the money I lost by taking my books off other vendors.

A year later, though, I don't think this is the case anymore. My self-published series is much more well known and my ability to advertise has grown with it. With these two factors, I'm hoping that I can the sales on non-Amazon vendors that will blow past the money I was making in KU.

Will it work? I have no idea. But part of the joy of being self published is the freedom to try new things. If I put my books on the other vendors and they flop, I might be coming back to KU, because it is a very good program. But whether or not it's the right program for me right now--or for you, or for any author--completely depends on our own unique situations.

That's why discussions like these are so important. Businesses, especially cottage industries like self-publishing, are all about knowing when to take smart risks, and determining what makes a risk smart or dumb is entirely a matter of information. No one can look into the future and predict if a novel will soar or flop, but the more we know and the deeper we understand how the modern book selling machine functions, the more confident we can be in our choices. And really, what more could you ask for?

BONUS! An Unexpected Benefit!

In addition to all the stuff I said above, there is a new, insanely cool new feature coming in with the new KU payment system, and that is Amazon's promise to report much more detailed KU borrow information!

Just think what that kind of information could do for your writing! It would give authors a window into where we lose people. I mean, just imagine if you could see the exact point where 50% of your readers quit. Clearly, there's something wrong with that part of the book, and while that would suck to see on a finished work, knowing where the problem is means you can fix it. I'm not saying we should go back and obsessively edit finished books, that way lies madness, but the option would be there if we wanted it, and that is a miracle compared to the old Traditional Publishing system of releasing a book into the wild and being trapped with that version forever.

If nothing else, I'd be happy just to get some more information. Anything's better than the current report, which is just a number of borrows with zero context.

And That's It!

I hope you've enjoyed this in depth look into the pros and cons of the new KU! If you disagree with my conclusions, or if there's an aspect you feel I left out, please leave it in the comments below. I'd really love to hear how these changes are affecting other writers on the front-lines of self publishing.

Thank you as always for reading, and I'll see you on Wednesday for another Writing Wednesdays post!

Hearts and ponies forever,Rachel

Since any change to KU is the definition of Relevant to My Interests, I proceeded to be very rude and looked it up right there at the table, and you know what? I really liked what I read, and here's why.

Amazon's imagery was more right than they knew. It's a wild sea out there.

Amazon's imagery was more right than they knew. It's a wild sea out there.Unlike many authors I talk to who tend to see Amazon'g book subscription service as EEEEVIIIIIIIL, I've been a pretty big fan of KU since Amazon announced it last year. I wrote a post breaking down the math of why KU should make everyone a lot of money back when it was first announced, and my opinion is pretty much the same now as it was then: that the Amazon exclusivity requirement sucks, but overall KU participation should be a good deal for most authors.

I'm pleased to report that my own experience with the program has been largely positive. I've been in KU for a year now, and while it's been much better for my fiction than 2k to 10k, I don't really have complaints on either score. That said, I will be taking my books out of KU later this year to try out other venues (gotta try new things!), but that decision is based entirely on wanting to reach out to new, non-Amazon markets, not because I'm dissatisfied with the program.

BUT (you knew there was a but, right?), as much as I personally love the idea and most of the practice of KU, it's no secret that the payment system was notoriously easy to game. Scamming was ridiculously rampant, and that's the problem this new KU payment system seeks to remedy.

How Kindle Unlimited Worked

Kindle Unlimited pays authors out of a fund set up by Amazon. Think of it as a large pie that Amazon slices up and doles out to its authors based on how many KU subscribers read their books. Previously, your slice of the pie was calculated based on how many KU readers borrowed your book and read to at least the 10% mark. Short story, graphic novel, epic Fantasy tome, doesn't matter. So long as they made it to that 10% mark, you got paid the full borrow amount (usually about $1.33), regardless of how long your book was or whether or not that reader actually finished it.

I'm sure you can already see the problems inherent to this set up. Almost as soon as Amazon posted these rules, the online bookstore was flooded with ten page "novels" written by people like "James Paterson," "Steven King," and "Norah Roberts." These titles were deliberate scams designed to trick KU readers into clicking on what they thought was a new release by a mega bestseller. Under the old KU rules, it didn't even matter if they instantly realized they'd been scammed. With a 10 page book, they only needed to look at one page in order for it to count as the 10% read the scammer needed to get paid the full KU payout.

Since all KU authors are paid out of the same pot, these scams hurt everyone. Not only were scammers sucking money away from legitimate authors, they were infuriating readers and making KU itself look bad. Amazon knew this and ruthlessly cracked down, but it was like fighting a hydra. Strike one scammer down and two more would pop up in their place. So, in order to save Kindle Unlimited (and themselves a ton of policing), Amazon changed the rules.

How Kindle Unlimited Will Work Starting July 1, 2015 (and Why It Rocks)

Starting next month, Kindle Unlimited will now pay out by pages read. Showing that Amazon has learned from their mistakes, this new system works off an algorithm that averages ebook page counts by total wordcount (so you can't just give all your books huge fonts and tons of white space) and starts the reader on the Prologue/Chapter 1 (so you can't just add tons of obviously skip-able front matter to pad your page count). In order to get paid the maximum borrow amount, a book will have to have quality content that captures and holds the reader's attention all the way to the end. (You know, the stuff that should be there anyway.)

Personally, I'm a HUGE fan of this change. I love the idea that Amazon is literally paying KU authors for being good writers instead of just good marketers. Under this system, authors who write good books people want to read are the ones who reap the maximum reward.

I also love that it incentivizes longer books, because I really dislike the current practice of chopping up would would otherwise be a single novel into multiple "serial" segments to maximize revenue. Not that I think any author who did this is evil or a scammer. Business is all about figuring out ways to get the maximum profit from your investment, and there is no arguing that you made a lot more money from borrows and sales off five 20k titles priced at $2.99 each than off one 100k novel priced at $4.99. But while some authors love the idea of serials and wrote them legitimately, KBoards and other self pub hangouts were constantly barraged with authors asking if they should cut up their novels into serial format simply because of the situation I described above, and I think that sucks.

When a system encourages artists to put their work into a format readers hate (and make no mistake, readers HATE serials. Just look at the reviews for any top selling serial and and you'll see what I mean), that's a bad system. It's bad for readers, it's bad for authors, it's bad for the book business in general. You want people to be happy when they finish your story, not pissed because they're having to buy/borrow 5 books to get one novel's worth of story.

I think Amazon became very aware of this, and the new KU borrow system is a step toward addressing it. Now, instead of encouraging authors to put out as many titles as possible, length be damned, Amazon is financially rewarding authors who tell good stories, regardless of format. When it comes to KU at least, the 100k word novel sold as one title will earn exactly the same as the 100k novel divided up into five 20k segments, encouraging novelists to write in the way that best suits the story.

As a writer who firmly believes that a story should be exactly as long or short as it needs to be, and as a reader who loathes arbitrary serial fiction (again, not talking about stories that are actually written to be serial format, but books that have been obviously chopped up just to take advantage of Amazon's payment structure), this is a HUGE change for the better. I am fully behind these new KU changes, and I hope Amazon takes more steps like this in the future.

But Rachel, How Can You Support the New KU Changes When They're Hurting Short Story Writers?!

When you look at the complaints leveled against the new KU, almost all of them come from two camps: short story writers, and authors who feel they should be paid for any amount of reading, regardless of whether or not the reader finishes the book.

Of these two groups, my heart goes out of the short story writers the most. Short stories are a very demanding form of fiction, and I fully respect the work that goes into them. That said, I don't think Amazon's new system is unfair, because no matter how much you put into your short fiction, it's still short. A short story might be deeper than the abyssal trench and more beautiful than a rainbow at sunrise, but the fact remains that it still takes less time to read and produce than a novel-length work of comparable quality.

In that light, I feel that the new system is actually more fair to authors since it rewards novelists and short story writers equally for their efforts rather than paying the same for 1,000 words as for 100,000 as was the case before. It's also more in line with the rest of the industry that has always paid by the word for short fiction. Plus, you can still charge whatever you want for people to buy your story, so it's not like Amazon's taking away your ability to make money off your short fiction. I do sympathize with the fact that you can no longer make $1.33 off a borrow on a $0.99 short story, but we all knew that gravy train had to dry up sometime ;).

But while I admit this new system is less advantageous to short fiction, I still think it's a good change over all. Fewer scammers gumming up the KU library improves the discoverability of quality books, and that means more borrows and more money for everyone!

As for the second group, the ones who feel they should get a full borrow price for any reading regardless of whether the reader finishes or not...you're entitled to that opinion. I don't agree, of course, but I'm not going to tell you how to feel. Personally, though, I think that if the KU part of your business model depends on getting your money up front because you're not confident readers are going to read your book all the way to the end, you have a much bigger problem than how KU borrows are calculated.

Wow, That's a Lot of Praise. So Are You 100% Behind the New KU?

Well, about that. I've always thought KU was a pretty good program, and these new changes make it even better. But while Amazon has addressed some of the problems with the KU model, they haven't touched what I see as the two greatest problem with the program: the Amazon exclusivity requirement, and fact that payments are still made out of the KDP Select Global Fund.

Where Things Get Less Awesome

While I love love LOVE the idea that KU has abandoned as single payout at 10% in favor of paying a small bounty per page read, just how much this per-page payment will be is impossible to say since Kindle Unlimited pays authors out of a fund that changes every month.

Let me be blunt: I REALLY f-ing hate this system. If you need a refresher for why it sucks, here is how Amazon explains the rules.

We base the calculation of your share of the KDP Select Global Fund by how often Kindle Unlimited customers choose and read more than 10% of your book, and Kindle Owners' Lending Library customers download your book. We compare these numbers to how often all participating KDP Select titles were chosen. For example, if the monthly global fund amount is $1,000,000, all participating KDP titles were read 300,000 times, and customers read your book 1,500 times, you will earn 0.5% (1,500/300,000 = 0.5%), or $5,000 for that month.Obviously, this part of their website hasn't been updated with the new KU rules, but you get the general idea. How much authors earn from enrolling their books in KU fluctuates from month to month based on how many titles are currently in the program, how many readers are borrowing, and how much money Amazon's Magic 8-Ball tells it to put into the fund. This volatility plus the fact that participating in KU means making your titles exclusive to Amazons makes it extremely difficult for authors like me to say whether or not borrow payments from KU are worth taking our titles off every other vendor.

When you earn your living off your books, that is some vitally important math. I know it seems weird after spending this entire post singing the new KU's praises, but this complete lack of reliable numbers and the odious Amazon exclusivity requirement is why I've decided take my books out of KU when the agreement expires later this year, and why One Good Dragon Deserves Another will not be included in the program at all in the foreseeable future.

Again, it's not because I haven't been making money--I've made lovely money off KU over the last year--it's just because that money isn't enough to outweigh the cost of not making my book available in every other market. And that's really kind of a shame, because my novels are exactly the kind of books that would do the best under the new KU system.

So Is the New KU Worth It?

That depends on you.

When I first signed up for KU, I was seeing one sale of my self-published titles on other vendors for every one hundred I was getting from Amazon. By that math, KU was totally worth it for me. Even at an insanely low $1 per borrow (a worst-case scenario that KU has never actually hit), I only needed about 10 borrows a day to make up all the money I lost by taking my books off other vendors.

A year later, though, I don't think this is the case anymore. My self-published series is much more well known and my ability to advertise has grown with it. With these two factors, I'm hoping that I can the sales on non-Amazon vendors that will blow past the money I was making in KU.

Will it work? I have no idea. But part of the joy of being self published is the freedom to try new things. If I put my books on the other vendors and they flop, I might be coming back to KU, because it is a very good program. But whether or not it's the right program for me right now--or for you, or for any author--completely depends on our own unique situations.

That's why discussions like these are so important. Businesses, especially cottage industries like self-publishing, are all about knowing when to take smart risks, and determining what makes a risk smart or dumb is entirely a matter of information. No one can look into the future and predict if a novel will soar or flop, but the more we know and the deeper we understand how the modern book selling machine functions, the more confident we can be in our choices. And really, what more could you ask for?

BONUS! An Unexpected Benefit!

In addition to all the stuff I said above, there is a new, insanely cool new feature coming in with the new KU payment system, and that is Amazon's promise to report much more detailed KU borrow information!

"When we make this change on July 1, 2015, you'll be able to see your book's KENPC listed on the "Promote and Advertise" page in your Bookshelf, and we'll report on total pages read on your Sales Dashboard report." - From the new KU AnnouncementI'm not sure exactly what the above means, but I'm ready for any expansion to the current "X number of borrows per day" tally. The best thing that could happen would be some kind of chart that would show you exactly where the average borrowing reader put your book down.